Impact of Pricing Practice Management on Performance and Sustainability of Supermarkets in the Urban Area of Enugu State, Nigeria

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- i.

- Determine the impact of adopting value-informed pricing practice, competition-informed pricing practice and cost-informed pricing practice on performance and sustainability of supermarkets in urban Enugu.

- ii.

- Establish the impact of adopting value-informed pricing practice, competition-informed pricing practice, and cost-informed pricing practice on performance and sustainability of supermarkets in urban Enugu, when high relative product advantage or intense competition is a moderating variable.

- iii.

- Establish the impact of adopting value-informed pricing practice, competition-informed pricing practice and cost-informed pricing practice on performance and sustainability of supermarkets in urban Enugu, when high relative product advantage and intense competition are moderating variables.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Value-Informed Pricing Practice

2.2. Competition-Informed Pricing Practice

2.3. Cost-Informed Pricing Practice

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Game Theory

3.2. Prospect Theory

- It identifies price as reference-dependent. Just like adaptation-level [11,50] and assimilation–contrast [51] theories, which lends credence to price as a reference point [52], prospect theory identifies opinions and perceptions to be relative. Appraisal of the acceptability of a new price entails comparison with a reference price, and the variations in price play a key role. The prospect theory, however, takes these theories further by declaring as gains, prices lower than the reference price, and declaring as losses, prices above the reference price.

- Diminishing sensitivity to the variations in price. This means that the value function is concave for gains, and convex for losses. Supermarket managers are affected in two ways by this tenet. Firstly, gain or loss has a more minor effect than the equivalent prior amount. Thus, gaining or losing N1000 is not 10 times as gratifying or as unpleasant as gaining or losing N100. Secondly, proportionality rather than absolute value determines the reception of new prices. This means that an increase from N10 to N17 hits much harder than a price increase from N80 to N87.

- Customers hate to lose. The aversion to loss is such that pain recorded at price increase is greater than the joy recorded at a price decrease. This asymmetry is evident in customers’ reaction to the price of chicken, for instance, increased from N1300 to N1600 as against a decrease from N1300 to N1000. There is usually buyer’s resistance in the former and a weaker sense of having gained, in the later.

4. Proposed Model and Hypotheses

Research Hypothesis

5. Research Method

6. Regression Analysis

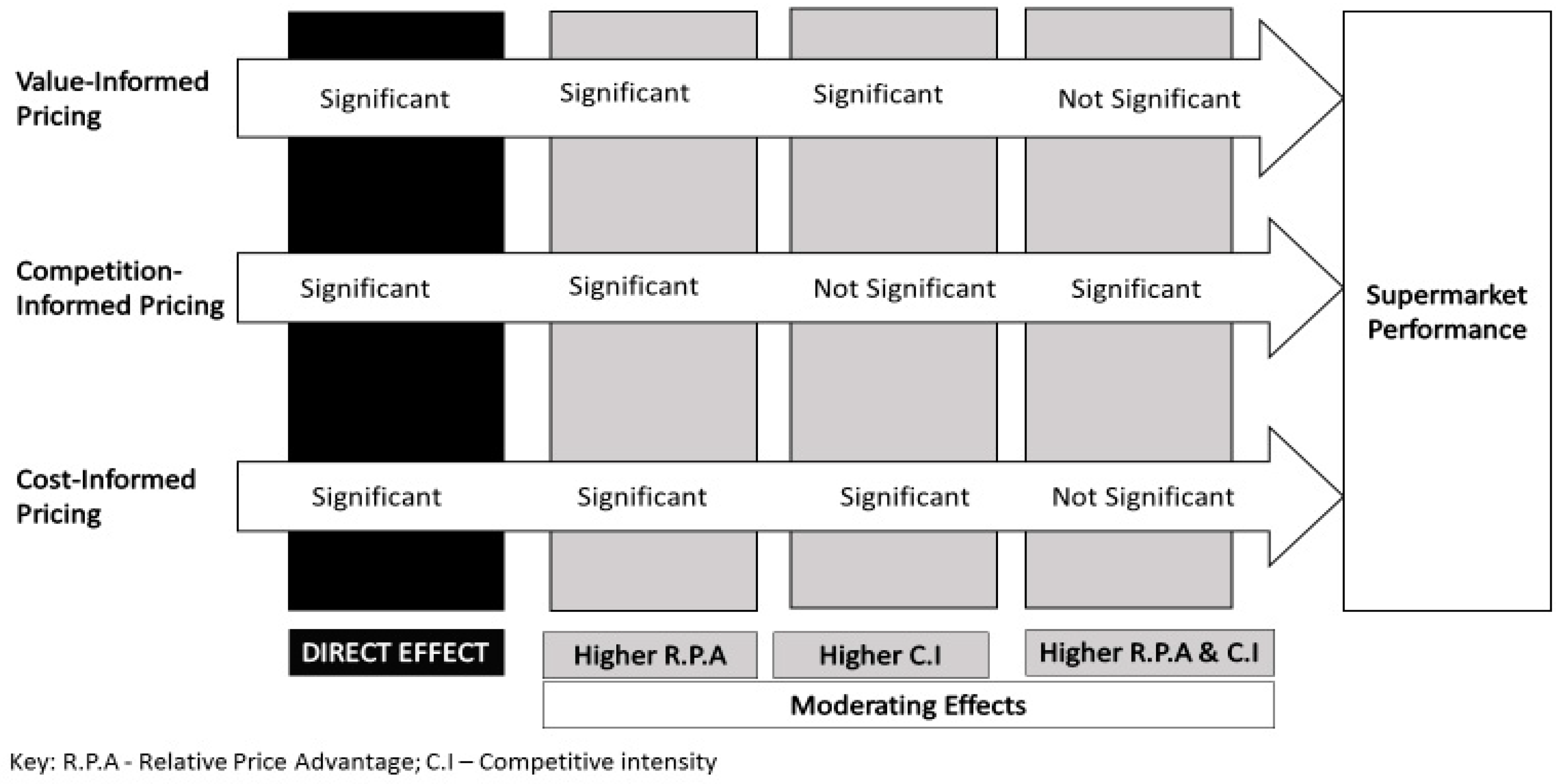

7. Results and Discussion

8. Conclusions

- ▪

- Value-informed pricing practice should be used by the management of supermarkets when there is high relative product advantage; i.e., only when the advantages of the particular product is far superior to those of close substitutes.

- ▪

- Competition-informed pricing practice should not be adopted by the management of supermarkets for products with intense competition or/and high relative product advantage.

- ▪

- Cost-informed pricing practice should be a dominant pricing practice in the mix of pricing practices adopted by the management of supermarkets, as its positive impact on the performance of supermarkets is very significant, especially in instances of intense competition for the product. However, when there is a high relative product advantage, cost-informed pricing practice should not be adopted.

- ▪

- The managers of pricing practices of supermarkets should critically carry out an internal and external environmental assessment of a product before deciding on the appropriate pricing practice to adopt for that product. Critical consideration should be given to the relative product advantage and the competitive intensity of the product. Moreover, the adopted pricing practice must be situated within the overall performance and sustainability objective of the firm in such a way that resources are optimized.

- ▪

- Cost-informed pricing practice should be adopted by the management of supermarkets in urban Enugu, when there is both low relative product advantage and highly competitive intensity. This will help maximize the opportunities that particular product presents in terms of performance and sustainability.

9. Limitations of the Study

10. Areas for Further Research

- i.

- Examining the effect of pricing practice management on performance and sustainability of supermarkets in Enugu State, Nigeria using a different methodology, more than one informant in one firm and secondary data that is more objective rather than primary data that is mostly viewed as a self-reported data by professional.

- ii.

- Examining the pricing practice management on performance and sustainability of manufacturing industry, and services industry in different geographical location, scope, and time frame, as well as using a larger population and sample size.

- iii.

- Examining the impact of other product and market characteristics that may influence the effectiveness of different price practices.

- iv.

- Extending the studies of pricing practice management on the patronage of the education sector in Nigeria.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| QUESTIONNAIRE | |

| Please [✓] appropriately whichever is chosen | |

| Section A: Background Characteristics | |

| 1. What is your sex? | |

| (a) Male | [ ] |

| (b) Female | [ ] |

| 2. Where does your age group fall? | |

| (a) 20–30 years | [ ] |

| (b) 30–40 years | [ ] |

| (c) 40 yeras and above | [ ] |

| 3. What is your marital status? | |

| (a) Single | [ ] |

| (b) Married | [ ] |

| (c) Divorce | [ ] |

| 4. What is your highest level of Academic qualification? | |

| (a) M.Sc, MBA, MA or above | [ ] |

| (b) B.Sc/HND | [ ] |

| (c) NCE/OND | [ ] |

| (d) WASSCE/GCE | [ ] |

| 5. Which Department do you work? | |

| (a) Account and Clearing Department | [ ] |

| (b) Store Department | [ ] |

| (c) Human Resources Department | [ ] |

| (d) Customer Services Department | [ ] |

| (e) Production | [ ] |

| (f) Safety Department/security | [ ] |

| (g) Cleaning Department/engineering | [ ] |

| (h) Others please state | [ ] |

| 6. What category of staff are you? | |

| (a) Senior | [ ] |

| (b) Junior | [ ] |

| 7. How long have you been a staff of this supermarkets? | |

| (a) Below one year | [ ] |

| (b) 1–3 years | [ ] |

| (c) 4–6 years | [ ] |

| (d) Above 6 years | [ ] |

| 8. Are you involved in the determination of the pricing of products of this supermarkets? | |

| (a) Yes | [ ] |

| (b) No | [ ] |

| Section B | |

| Tick [✓] against the most appropriate option to indicate the extent to which you agree with the following factors included in the price-setting process of your organization’s product? In other words: to what extent did your organization take into account the following elements while determining the price of products between 2016 to 2018? | |

| SA | Strongly Agree |

| A | Agree |

| D | Disagree |

| SD | Strongly Disagree |

| S/NO | OPTION | SA | A | D | SD |

| 1 | The advantages a product offers to consumers is considered when setting the prices of products | ||||

| 2 | The customers’ perceived value of the product is considered when setting the prices of products | ||||

| 3 | The advantages the product offers, in comparison to substitutes, is considered when setting the prices of products | ||||

| 4 | Balance between the possible advantages of the product and its possible price is considered when setting the prices of products |

| S/NO | OPTION | SA | A | D | SD |

| 5 | The price of competitors product is considered when setting the prices of products | ||||

| 6 | The current pricing practice/strategy of competitors is considered when setting the prices of products | ||||

| 7 | The estimation of the competitor’s strength and ability to react is considered when setting the prices of products | ||||

| 8 | The degree of competition (number and strength of competitors) is considered when setting the prices of products | ||||

| 9 | The competitive advantages of competitors on the market is considered when setting the prices of products |

| S/NO | OPTION | SA | A | D | SD |

| 10 | The cost of purchasing the product is considered when setting the prices of products | ||||

| 11 | The price necessary for break-even is considered when setting the prices of products | ||||

| 12 | Profit margin is set by the company for each product is considered when setting the prices of products |

| S/NO | OPTION | SA | A | D | SD |

| 13 | When a product has a higher quality in comparison with competing products, it reflects in your pricing of that product | ||||

| 14 | When a product solves a problem customers have with competing products, it reflects in your pricing of that product | ||||

| 15 | When a product is very innovative and substituted for another product, it reflects in your pricing of that product |

| S/NO | OPTION | SA | A | D | SD |

| 16 | Intense price competition is considered when setting the price of products | ||||

| 17 | Strong competitors sales, promotion, and distribution systems are considered when setting the price of products | ||||

| 18 | High quality competing products are considered when setting the price of products |

| S/NO | OPTION | SA | A | D | SD |

| 19 | Management has achieved our sales turnover objective since adopting the current pricing practice | ||||

| 20 | Management has achieved our profit objective since adopting the current pricing practice | ||||

| 21 | Management has achieved its market share objective since adopting the current pricing practice | ||||

| 22 | Management has achieved its competitive advantage objectives since adopting the current pricing practice |

References

- Dolan, R.J.; Simon, H. Power Pricing: How Managing Price Transforms the Bottom Line; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fader, P.S.; Lodish, L.M. A Cross-Category analysis of category structure and promotional activity for grocery products. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liozu, S.M.; Hinterhuber, A. Industrial product pricing: A value-based approach. J. Bus. Strategy 2012, 33, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoch, S.J.; Mary, P.; Xavier, D. The EDLP, HiLo, and margin arithmetic. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.; Weitz, B.A. Retailing Management, 3rd ed.; Richard, D., Ed.; Irwin/McGraw-Hill: Urbana, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, B.E.; Leigh, M. Grocery Revolution: The New Focus on the Consumer; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dudu, O.F.; Agwu, E. A review of the effect of pricing strategy on the purchase of consumer goods. Int. J. Res. Manag. Sci. Technol. 2018, 2, 88–102. [Google Scholar]

- Nyaga, P.K.; Muema, W. Effect of skimming pricing strategy on the profitability of insurance firms in Kenya. Int. J. Financ. Account. 2017, 2, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Deonir, D.; Gabriel, S.M.; Evandro, B.S.; Fabiano, L. Marketing pricing strategies and levels and their impact on corporate profitability. Manag. J. 2017, 52, 120–133. [Google Scholar]

- Imoleayo, O. The role of competition on the pricing decision of an organisation and the attainment of the organisational objective. Ann. Univ. Petroşani Econ. 2010, 10, 229–248. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson, N.; Kesteloo, M.; Hoogenberg, M. Pricing Is Not Only about Price: How Retailers Can Improve Their Price Image; A PWC Report; PricewaterhouseCoopers: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ingenbleek, P.; Van Der Lans, I.A. Relating price strategies and Price-Setting practices. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, P.M.; Thomas, S.G. Industrial Pricing: Theory and managerial practice. Mark. Sci. 1999, 18, 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noble, P.M.; Thomas, S.G. Response to the comments on “industrial pricing: Theory and managerial practice”. Mark. Sci. 1999, 18, 458–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stephan, M.L.; Andreas, H. Pricing orientation, pricing capabilities, and firm performance. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 594–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostis, I.; George, A. New industrial service pricing strategies and their antecedents: Empirical evidence from two industrial sectors. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2011, 26, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tzokas, N.; Susan, H.; Paraskevas, A.; Michael, S. Industrial export pricing practices in the United Kingdom. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2000, 29, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijsbrechts, E. Prices and pricing research in consumer marketing: Some recent developments. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1993, 10, 115–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressman, G.E., Jr. Value-Based pricing: A State-of-the-Art review. In Handbook on Business to Business Marketing; Lilien, G., Grewal, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, K.B.; Tradib, M. Pricing-Decision models: Recent developments and opportunities. In Issues in Pricing, Theory And Research; Devinney, T.M., Ed.; Lexington: Lexington, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 360–388. [Google Scholar]

- Oxenfeldt, A. A Decision-Making structure for price decisions. J. Mark. 2014, 37, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R. Pricing research in marketing: The state of the art. J. Bus. 2015, 57, S39–S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterhuber, A.; Liozu, A. Is innovation in pricing your nest source of competitive advantage. Bus. Horiz. 2014, 57, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avlonitis, G.; Indounas, K.A.; Gounaris, S.P. Pricing objectives over the service life cycle: Some empirical evidence. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 696–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, K.B. Princing Making Profitable Decisions, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- De Toni, D.; Mazzon, J.A. Testing a Theoretical Model on the Perceived Value of a Product’s Price. Revista de Adm. 2013, 49, 549–565. [Google Scholar]

- Hinterhuber, A.; Liozu, A. Innovation in Pricing: Contemporary Theories and Best Practices; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Liozu, S.M. Pricing Capabilities and Firm Performance: A Socio-Technical Framework for the Adoption of Pricing as a Transformational Innovation. Electronic Thesis or Dissertation. 2013. Available online: https://etd.ohiolink.edu/ (accessed on 18 July 2018).

- Nagle, T.; Holden, R.K. Pricing Strategies: Making the Decision; Prentice Hall: São Paulo, Brazil, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nagle, T.T.; Hogan, J.E. Strategy and Tactics—A Guide to Growing with Profitability; Pearson Education do Brasil: São Paulo, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, I. A study in price policy. Economica 1956, 23, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxall, G. A descriptive theory of pricing for marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 1972, 6, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonoma, V.; Victoria, L.; Robert, J. Can we have rigor and relevance in pricing research. In Issues in Pricing, Theory and Research; Timothy, M.D., Ed.; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988; pp. 337–359. [Google Scholar]

- Atuahene-Gima, K. An exploratory analysis of the impact of market orientation on new product performance-A contingency approach. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 1995, 12, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Christian, P. A Multiple-Layer model of Market-Oriented organizational culture: Measurement issues and performance outcomes. J. Mark. Res. 2000, 37, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achrol, S. Evolution of the marketing organization: New forms for turbulent environments. J. Mark. 1991, 55, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S.; David, B.M. Charting new directions for marketing. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterhuber, A. Customer Value-Based pricing strategies: Why companies resist. J. Bus. Strategy 2008, 29, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heil, O.P.; Helsen, K. Toward an understanding of price wars: Theirnature and how they erupt. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2001, 18, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.; Bilstein, F.F.; Luby, F. Manage for Profit, Not for Market Share; Bookman: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Milan, G.S.; De Toni, D.; Larentis, F.; Gava, A.M. Relation between pricing and costing strategies. J. Manag. Sci. 2013, 15, 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Urdan, A.T. Practices and Results of Apprehended Brazilian Companies; Research Report/2005; FGV/EASP: São Paulo, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gatignon, H.; Jean-Marc, X. Strategic orientation of the firm and new product performance. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, K.B. Pricing: Making Profitable Decisions; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Guilding, C.; Drury, C.; Tayles, M. An empirical investigation of the importance of Cost-Plus pricing. Manag. Audit. J. 2005, 20, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aumann, R. Agreeing to disagree. Ann. Stat. 1976, 4, 1236–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, P. An axiomatic characterization of common knowledge. Econometrica 1981, 49, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.; Skeath, S. Games of Strategy; Norton Company: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking Fast and Slow; Penguin: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Helson, H. Adaptation-Level Theory: An Experimental and Systematic Approach to Behavior; Harper Row: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif, M.; Hovland, C.I. Social Judgement: Assimilation and Contrast Effects on Communication and Attitude Change; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, J.L. A theoretical framework for formulating Non-Controversial prices for public park and recreation services. J. Leis. Res. 2011, 43, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füreder, R.; Maier, Y.; Yaramova, A. Value-based pricing in Austrian medium-sized companies. Strateg. Manag. 2014, 19, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ingenbleek, P.; Debruyne, M.; Frambach, R.T.; Verhallen, T.M. Successful new product pricing strategies: A contingency approach. Mark. Lett. 2003, 14, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sex of Respondents | |||

| Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative Percent | |

| Male | 35 | 73% | 73% |

| Female | 13 | 27% | 100% |

| Total | 48 | 100% | |

| Age of Respondents | |||

| Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative Percent | |

| 20–30 | 17 | 35% | 35% |

| 31–40 | 19 | 40% | 75% |

| 41+ | 12 | 25% | 100% |

| Total | 48 | 100% | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative Percent | |

| Single | 20 | 42% | 42% |

| Married | 28 | 58% | 100% |

| Divorced | 0 | 0% | 100% |

| Widowed | 0 | 0% | 100% |

| Total | 48 | 100% | |

| Educational Qualification | |||

| Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative Percent | |

| WASSCE | 0 | 0% | 0% |

| NCE/Diploma, OND | 4 | 8% | 8% |

| BSc/HND | 35 | 73% | 81% |

| Postgraduate | 9 | 19% | 100% |

| Others | 0 | 0% | 100% |

| Total | 48 | 100% | |

| Department of Respondents | |||

| Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative Percent | |

| Executive Management | 22 | 46% | 46% |

| Accounts | 4 | 8% | 54% |

| Store | 18 | 38% | 92% |

| HR | 0 | 0% | 92% |

| Customer Service | 4 | 8% | 100% |

| Safety Department | 0 | 0% | 100% |

| Total | 48 | 100% | |

| Category of Staff Respondents belong to | |||

| Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative Percent | |

| Senior | 42 | 88% | 88% |

| Junior | 6 | 12% | 100% |

| Total | 48 | 100% | |

| Years of Experience with the supermarket | |||

| Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative Percent | |

| Less than one year | 4 | 8% | 8% |

| 1–3 years | 22 | 46% | 54% |

| 4–6 years | 18 | 38% | 92% |

| Above 6 years | 4 | 8% | 100% |

| Total | 48 | 100% | |

| Involvement in the determination of pricing practice of the supermarket | |||

| Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative Percent | |

| Yes | 48 | 100% | 100% |

| No | 0 | 0% | 100% |

| Total | 48 | 100% | |

| S/No | Questionnaire Items | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The advantages a product offers to consumers is considered when setting the prices of products | 11 (22.9%) | 25 (52.1%) | 7 (14.6%) | 5 (10.4%) | 2.12 | 0.89 |

| 2 | The customers’ perceived value of the product is considered when setting the prices of products | 12 (25%) | 25 (52.1%) | 9 (18.8%) | 2 (4.2%) | 2.02 | 0.78 |

| 3 | The advantages the product offers, in comparison to substitutes, is considered when setting the prices of products | 13 (27.1%) | 23 (47.9%) | 7 (14.6%) | 5 (10.4%) | 2.08 | 0.91 |

| 4 | Consideration is given to both possible benefits and possible price of product when setting the prices of products | 13 (27.1%) | 23 (47.9%) | 10 (20.8%) | 2 (4.2%) | 2.01 | 0.81 |

| Total | 49 | 96 | 33 | 14 |

| S/No | Questionnaire Items | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean | Standard Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | The price of competitors product is considered when setting the prices of products | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (43.8%) | 27 (56.3%) | 3.43 | 0.50 |

| 6 | The current pricing practice/strategy of competitors is considered when setting the prices of products | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (43.8%) | 27 (56.3%) | 3.56 | 0.50 |

| 7 | The valuation of competitor’s strength and ability to respond is considered when setting the prices of products | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 25 (52.1%) | 23 (47.9%) | 3.47 | 0.50 |

| 8 | The degree of competition (number and strength of competitors) is considered when setting the prices of products | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 30 (62.5%) | 18 (37.5%) | 3.37 | 0.49 |

| 9 | The competitive 12 strength of competitors on the market is considered when setting the prices of products | 0 (0%) | 3 (6.3%) | 29 (60.4%) | 16 (33.3%) | 3.27 | 0.57 |

| Total | 0 | 3 | 126 | 111 |

| S/No | Questionnaire Items | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean | Standard Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | The cost of purchasing the product is considered when setting the prices of products | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 23 (47.9%) | 25 (52.9%) | 3.5 | 0.50 |

| 11 | The price necessary for break-even is a factor in setting the prices of products | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (37.5%) | 30 (62.5%) | 3.6 | 0.48 |

| 12 | Profit margin for each product is considerable factor in setting the prices of products | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (37.5%) | 30 (62.5%) | 3.6 | 0.48 |

| Total | 0 | 0 | 59 | 85 |

| S/No | Questionnaire Items | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean | Standard Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | When a product has a higher quality in comparison with competing products, it reflects in your pricing of that product | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 20 (41.7%) | 28 (58.3%) | 3.58 | 0.49 |

| 14 | When a product solves problems that customers have with competing products, it reflects in your pricing of that product | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 30 (62.5%) | 18 (37.5%) | 3.37 | 0.48 |

| 15 | When a product is very innovative and substituted for another product, it reflects in your pricing of that product | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 20 (41.7%) | 28 (58.3%) | 3.58 | 0.49 |

| Total | 0 | 0 | 70 | 74 |

| S/No | Questionnaire Items | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean | Standard Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | Intense price competition is considered when setting the price of products | 12 (25.0%) | 21 (43.8%) | 10 (20.8%) | 5 (10.4%) | 2.1 | 0.93 |

| 17 | Strong competitor sales, promotion, and distribution systems are considered when setting the price of products | 8 (16.7%) | 19 (39.6%) | 20 (41.7%) | 1 (2.1%) | 2.2 | 0.77 |

| 18 | High quality competing products are considered when setting the price of products | 10 (20.8%) | 24 (50.0%) | 12 (25.0%) | 2 (4.2%) | 2.1 | 0.78 |

| Total | 30 | 64 | 42 | 8 |

| S/No | Questionnaire items | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean | Standard Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | Management has achieved its sales turnover objective since adopting the current pricing practice | 0 (0%) | 14 (19.65%) | 23 (47.9%) | 11 (22.9%) | 2.9 | 0.72 |

| 20 | Management has achieved its profit objective since adopting the current pricing practice | 6 (12.5%) | 12 (25.0%) | 19 (39.6%) | 11 (22.9%) | 2.7 | 0.96 |

| 21 | Management has achieved its market share objective since adopting the current pricing practice | 2 (4.2%) | 20 (41.7%) | 22 (45.8%) | 4 (8.3%) | 2.5 | 0.70 |

| 22 | Management has achieved its competitive advantage objectives since adopting the current pricing practice | 6 (12.5%) | 28 (58.3%) | 13 (27.1%) | 1 (2.1%) | 2.1 | 0.67 |

| Total mean | 2.55 | ||||||

| # | Equation | Model Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Equation (1) | OP = 1.827 + 0.004VIP − 0.152CIP + 0.767CTIP + µ1 (0.5632) (0.6988) (0.0802) (0.0000) | R-Squared = 0.51 |

| R-BAR-Squared = 0.48 | ||

| S.E of Regression = 163.35 | ||

| F-Stat. F(3,45) = 20.3449 (0.0023) | ||

| Mean Dependent Variable = 87.63 | ||

| DW-Statistics = 2.1 | ||

| Equation (2) | OP = 1.76 + 0.053VIP − 0.345CIP + 0.523CTIP − 0.321RPA + µ2 (0.653) (0.0608) (0.0102) (0.093) (0.087) | R-Squared = 0.58 |

| R-BAR-Squared = 0.53 | ||

| S.E of Regression = 173.53 | ||

| F-Stat. F(4,44) = 24.0149 (0.0023) | ||

| Mean Dependent Variable = 87.63 | ||

| DW-Statistics = 1.52 | ||

| Equation (3) | OP = 1.892 + 0.002VIP − 0.35088CIP + 0.822CTIP − 0.234CI + µ3 (0.5632) (0.169) (0.080) (0.000) (0.0303) | R-Squared = 0.56 |

| R-BAR-Squared = 0.49 | ||

| S.E of Regression = 113.53 | ||

| F-Stat. F(3,45) = 22.797 (0.0025) | ||

| Mean Dependent Variable = 78.36 | ||

| DW-Statistics = 1.7 | ||

| Equation (4) | OP = 1.992 + 0.004VIP − 0.2601CIP + 0.789CTIP − 0.3104RPA − 0.221CI + µ4 (0.5632) (0.5443) (0.0914) (0.000) (0.0873) (0.0474) | R-Squared = 0.62 |

| R-BAR-Squared = 0.55 | ||

| S.E of Regression = 134.32 | ||

| F-Stat. F(3,45) = 23.991 (0.0021) | ||

| Mean Dependent Variable = 97.34 | ||

| DW-Statistics = 1.9 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Agbaeze, E.; Chiemeke, M.N.; Ogbo, A.; Ukpere, W.I. Impact of Pricing Practice Management on Performance and Sustainability of Supermarkets in the Urban Area of Enugu State, Nigeria. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6019. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156019

Agbaeze E, Chiemeke MN, Ogbo A, Ukpere WI. Impact of Pricing Practice Management on Performance and Sustainability of Supermarkets in the Urban Area of Enugu State, Nigeria. Sustainability. 2020; 12(15):6019. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156019

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgbaeze, Emmanuel, Maureen Ngozichukwu Chiemeke, Ann Ogbo, and Wilfred I. Ukpere. 2020. "Impact of Pricing Practice Management on Performance and Sustainability of Supermarkets in the Urban Area of Enugu State, Nigeria" Sustainability 12, no. 15: 6019. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156019