Seeking Sustainable Development in Teams: Towards Improving Team Commitment through Person-Group Fit

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Person-Environment (PE) Fit and Multiple Targets of Commitment

2.2. PG Fit and Team Commitment

2.3. Interactive Effects of the Multiple Types of Fit on Work-Related Outcomes

2.4. PO Fit as a Moderator

2.5. PS Fit as a Moderator

2.6. Three-Way Interactive Effects of PG Fit, PO Fit, and PS Fit on Team Commitment

3. Methods

3.1. Data and Sample

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Control Variables

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Examination of Common Method Bias

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jackson, C.L.; Lepine, J.A. Peer responses to a team’s weakest link: A test and extension of LePine and Van Dyne’s model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- LePine, J.A.; Van Dyne, L. Peer responses to low performers: An attributional model of helping in the context of groups. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-Supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, J.Y.; Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Park, W.W.; Hong, D.S.; Shin, Y. Person-group fit: Diversity antecedents, proximal outcomes, and performance at the group level. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1184–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, J.Y.; Kristof-Brown, A.L. Testing multidimensional models of person-group fit. J. Manag. Psychol. 2012, 27, 536–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Jansen, K.J.; Colbert, A.E. A policy-capturing study of the simultaneous effects of fit with jobs, groups, and organizations. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-Y.; Kim, M. Leaders’ moral competence and employee outcomes: The effects of psychological empowerment and person–supervisor fit. J. Bus. Ethic 2013, 112, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwater, L.; Dionne, S. A process model of leader-follower fit. In Perspectives on Organizational Fit; Ostroff, C., Judge, T.A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 183–208. [Google Scholar]

- Dansereau, F.; Graen, G.; Haga, W.J. A vertical dad linkage approach to leadership within formal organizations: A longitudinal investigation of the role making process. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1975, 13, 46–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epitropaki, O.; Martin, R. LMX and work attitudes: Is there anything left unsaid or unexamined? In The Oxford Handbook of Leader-Member Exchange; Bauer, T.N., Erdogan, B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R.; Guillaume, Y.R.F.; Thomas, G.; Lee, A.; Epitropaki, O. Leader-member exchange (LMX) and performance: A meta-analytic review. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 69, 67–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matta, F.K.; Van Dyne, L. Leader-member exchange and performance: Where we are and where we go from here. In The Oxford Handbook of Leader-Member Exchange; Bauer, T.N., Erdogan, B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 157–173. [Google Scholar]

- Astakhova, M.N. Explaining the effects of perceived person-supervisor fit and person-organization fit on organizational commitment in the U.S. and Japan. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vianen, A.E.; Shen, C.-T.; Chuang, A. Person-organization and person-supervisor fits: Employee commitments in a Chinese context. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 906–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sekiguchi, T. How organizations promote person-environment fit: Using the case of Japanese firms to illustrate institutional and cultural influences. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2006, 23, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, T.; Huber, V.L. The use of person–organization fit and person–job fit information in making selection decisions. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2011, 116, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R. An examination of competing versions of the person-environment fit approach to stress. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 292–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edwards, J.R. Person-environment fit in organizations: An assessment of theoretical progress. Acad. Manag. J. Ann. 2008, 2, 167–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchinsky, P.M.; Monahan, C.J. What is person-environment congruence? Supplementary versus complementary models of fit. J. Vocat. Behav. 1987, 31, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Chatman, J.; Caldwell, D.F. People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 487–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saks, A.M.; Ashforth, B.E. A longitudinal investigation of the relationships between job information sources, applicant perceptions of fit, and work outcomes. Pers. Psychol. 1997, 50, 395–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrow, J.B.; Behrend, T.S. Person-environment fit is a formative construct. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 103, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, K.J.; Kristof-Brown, A.L. Toward a multidimensional theory of person-environment fit. J. Manag. Issues 2006, 18, 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, I.-S.; Guay, R.P.; Kim, K.; Harold, C.M.; Lee, J.-H.; Heo, C.-G.; Shin, K.-H. Fit happens globally: A meta-analytic comparison of the relationships of person-environment fit dimensions with work attitudes and performance across East Asia, Europe, and North America. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 67, 99–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroff, C.; Schulte, M. Multiple perspectives of fit in organizations across levels of analysis. In Perspectives on Organizational Fit; Ostroff, C., Judge, T.A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, R.M.; Feldman, D.C. Integrating the levels of person-environment fit: The roles of vocational fit and group fit. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 75, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof, A.L. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salthouse, T.A. Refining the concept of psychological compensation. In Compensating for Psychological Deficits and Declines: Managing Losses and Promoting Gains; Dixon, R.A., Bäckman, L., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1995; pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckman, L.; Dixon, R.A. Psychological compensation: A theoretical framework. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adkins, C.L.; Russell, C.; Werbel, J.D. Judgments of fit in the selection process: The role of work value congruence. Pers. Psychol. 1994, 47, 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E.T.; Billings, R.; Eveleth, D.; Gilbert, N.L. Foci and bases of employee commitment: Implications for job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 464–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D.; Morgan, R.M. Organizational commitment: One of many commitments or key mediating construct? Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 1568–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichers, A.E. A review and reconceptualization of organizational commitment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasti, S.A.; Can, O. Affective and normative commitment to organization, supervisor, and coworkers: Do collectivist values matter? J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Stevens, C.K. Goal congruence in project teams: Does the fit between members’ personal mastery and performance goal matter? J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretz, R.D.; Judge, T.A. Person–organization fit and the theory of work adjustment: Implications for satisfaction, tenure, and career success. J. Vocat. Behav. 1994, 44, 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretz, R.D.; Rynes, S.L.; Gerhart, B. Recruiter perceptions of applicant fit: Implications for individual career preparation and job search behavior. J. Vocat. Behav. 1993, 43, 310–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. An overview (and underview) of research and theory within the attraction paradigm. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1997, 14, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.; Abrams, D. Social Identification; Routledge: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Seong, J.Y.; Hong, D.S. Interaction of person-group fit: Supplementary fit and complementary fit go together? Presented at the 76th-Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Anaheim, CA, USA, 7–11 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Resick, C.J.; Baltes, B.B.; Shantz, C.W. Person-organization fit and work-related attitudes and decisions: Examining interactive effects with job fit and conscientiousness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1446–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, B.J.; Woehr, D.J. A quantitative review of the relationship between person–organization fit and behavioral outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verquer, M.L.; Beehr, T.A.; Wagner, S.H. A meta-analysis of the relations between person-organization fit and work attitudes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werbel, J.D.; Johnson, D.J. The use of person-group fit for employment selection: A missing link in person-environment fit. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2001, 40, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, M.R. Acculturation in the workplace: Newcomers as lay ethnographers. In Organizational Culture and Climate; Schneider, B., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 85–129. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Political Psychology; Informa UK Limited: Informa, UK, 1986; pp. 276–293. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, T.E. Foci and bases of commitment: Are they distinctions worth making? Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatman, J.A. Improving interactional organizational research: A model of person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- French, J.R.P., Jr.; Rogers, W.; Cobb, S. Adjustment as person-environment fit. In Coping and Adaptation; Coelho, G.V., Hamburg, D.A., Adams, J.E., Eds.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 316–333. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, B. The people make the place. Pers. Psychol. 1987, 40, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.N.; Green, S.G. The development of leader-member exchange: A longitudinal test. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 1538–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meglino, B.M.; Ravlin, E.C.; Adkins, C.L. A work value approach to corporate culture: A field test of the value congruence process and its relationship to individual outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, J.; Lam, S.S. How similarity to peers and supervisor influences organizational advancement in different cultures. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 1120–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Senger, J. Manager’s perceptions of subordinates’ competence as a function of personal value orientations. Acad. Manag. J. 1971, 14, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjosvold, D. Power and social context in superior-subordinate interaction. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1985, 35, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Sparrowe, R.T.; Wayne, S.J. Leader-member exchange theory: The past and potential for the future. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1997, 15, 47–119. [Google Scholar]

- Rockstuhl, T.; Dulebohn, J.H.; Ang, S.; Shore, L.M. Leader-member exchange (LMX) and culture: A meta-analysis of correlates of LMX across 23 countries. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 1097–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Decoster, S.; Camps, J.; Stouten, J.; Vandevyvere, L.; Tripp, T.M. Standing by your organization: The impact of organizational identification and abusive supervision on followers’ perceived cohesion and tendency to gossip. J. Bus. Ethic 2013, 118, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schyns, B.; Schilling, J. How bad are the effects of bad leaders? A meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes. Lead. Q. 2013, 24, 138–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Vegt, G.S.; Bunderson, J.S.; Van Der, G.S. Learning and performance in multidisciplinary teams: The importance of collective team identification. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 532–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, S.C.; Huffman, A.H. A longitudinal examination of the influence of mentoring on organizational commitment and turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Quinn, R.E.; Rohrbaugh, J. A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: Towards a competing values approach to organizational analysis. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, J.; Richter, A.W. Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: Development and application of a slope difference test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepper, B.J.; Dimotakis, N.; Lambert, L.S.; Koopman, J.; Matta, F.K.; Park, H.M.; Goo, W.; Goo, W. Examining follower responses to transformational leadership from a dynamic, person–environment fit perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 1343–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bruce, K.; Nyland, C. Elton Mayo and the deification of Human Relations. Organ. Stud. 2011, 32, 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, E.S. The politics of management thought: A case study of the Harvard Business School and the Human Relations School. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roethlisberger, F.J.; Dickson, W.J. Management and the Worker; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, R.; Puranam, P. Renewal through reorganization: The value of inconsistencies between formal and informal organization. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soda, G.; Zaheer, A. A network perspective on organizational architecture: Performance effects of the interplay of formal and informal organization. Strat. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 751–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Chung, M.H.; Labianca, G. Group social capital and group effectiveness: The role of informal socializing ties. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 860–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level, multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, M.G. A Monte Carlo study of the effects of correlated method variance in moderated multiple regression analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1985, 36, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemsen, E.; Roth, A.; Oliveira, P. Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 13, 456–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obstfeld, D. Social networks, the tertius lungens orientation, and involvement in innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 100–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Seong, J.Y.; DeGeest, D.; Park, W.W.; Hong, D.S. Testing the homology of person-group fit: A multilevel analysis of supplementary and complementary fit. Presented at the Academy of Management Annual Meeting, Academy of Management, San Antonio, TX, USA, 7–11 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis, H.C. Individualism and collectivism: Past, present, and future. In The Handbook of Culture and Psychology; Matsumoto, D., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

| Model | Description | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | RMR | Change from Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δχ2 | Δdf | |||||||||

| 1 | One-factor model a | 798.12 *** | 104 | 7.67 | 0.65 | 0.60 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 604.53 | 6 |

| 2 | Two-factor model b | 652.12 *** | 103 | 6.33 | 0.72 | 0.68 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 458.53 | 5 |

| 3 | Three-factor model c | 456.54 *** | 101 | 4.52 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 262.95 | 3 |

| 4 | Four-factor model d | 193.59 *** | 98 | 1.97 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.07 | 0.04 | ||

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Gender | 1.15 | 0.35 | - | |||||||

| 2. | Age | 1.89 | 0.72 | 0.46 ** | - | ||||||

| 3. | Rank | 1.85 | 0.95 | 0.37 * | 0.59 ** | - | |||||

| 4. | Tenure | 2.80 | 1.51 | −0.45 ** | −0.15 | 0.55 ** | - | ||||

| 5. | PG fit | 3.61 | 0.63 | −0.22 ** | −0.18 * | 0.18 * | 0.02 | (0.89) | |||

| 6. | PO fit | 3.46 | 0.65 | −0.17 * | −0.10 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.59 ** | (0.92) | ||

| 7. | PS fit | 3.35 | 0.79 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.04 | −0.05 | 0.43 ** | 0.51 ** | (0.89) | |

| 8. | Team Commitment | 3.70 | 0.79 | −0.25 ** | −0.11 | 0.18* | −0.01 | 0.65 ** | 0.65 ** | 0.55 ** | (0.93) |

| X | Y | M | |

|---|---|---|---|

| X (PG fit) | (0.89) | ||

| Y (Team commitment) | 0.65 *** | (0.80) | |

| M (Organizational culture) | 0.11 | 0.04 | (0.80) |

| ryx.m | 0.67 *** |

| Team Commitment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Step 1 | Gender | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.03 |

| Age | 0.28 ** | 0.16 * | 0.17 * | 0.17 * | |

| Rank | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.06 | |

| Tenure | −0.20 * | −0.12 | −0.11 | −0.10 | |

| Step 2 | PG fit | 0.34 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.40 *** | |

| PO fit | 0.30 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.31 *** | ||

| PS fit | 0.24 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.33 *** | ||

| Step 3 | PG fit × PO fit | 0.04 | 0.04 | ||

| PG fit × PS fit | −0.14 + | −0.17 * | |||

| PO fit × PS fit | 0.07 | 0.13 | |||

| Step 4 | PG fit × PO fit × PS fit | −0.17 * | |||

| Overall F | 3.93 ** | 31.33 *** | 22.34 *** | 21.22 *** | |

| R2 | 0.09 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.62 | |

| F change | 3.93 ** | 61.64 *** | 1.15 | 4.59 * | |

| R2change | 0.09 ** | 0.50 *** | 0.01 | 0.01 * | |

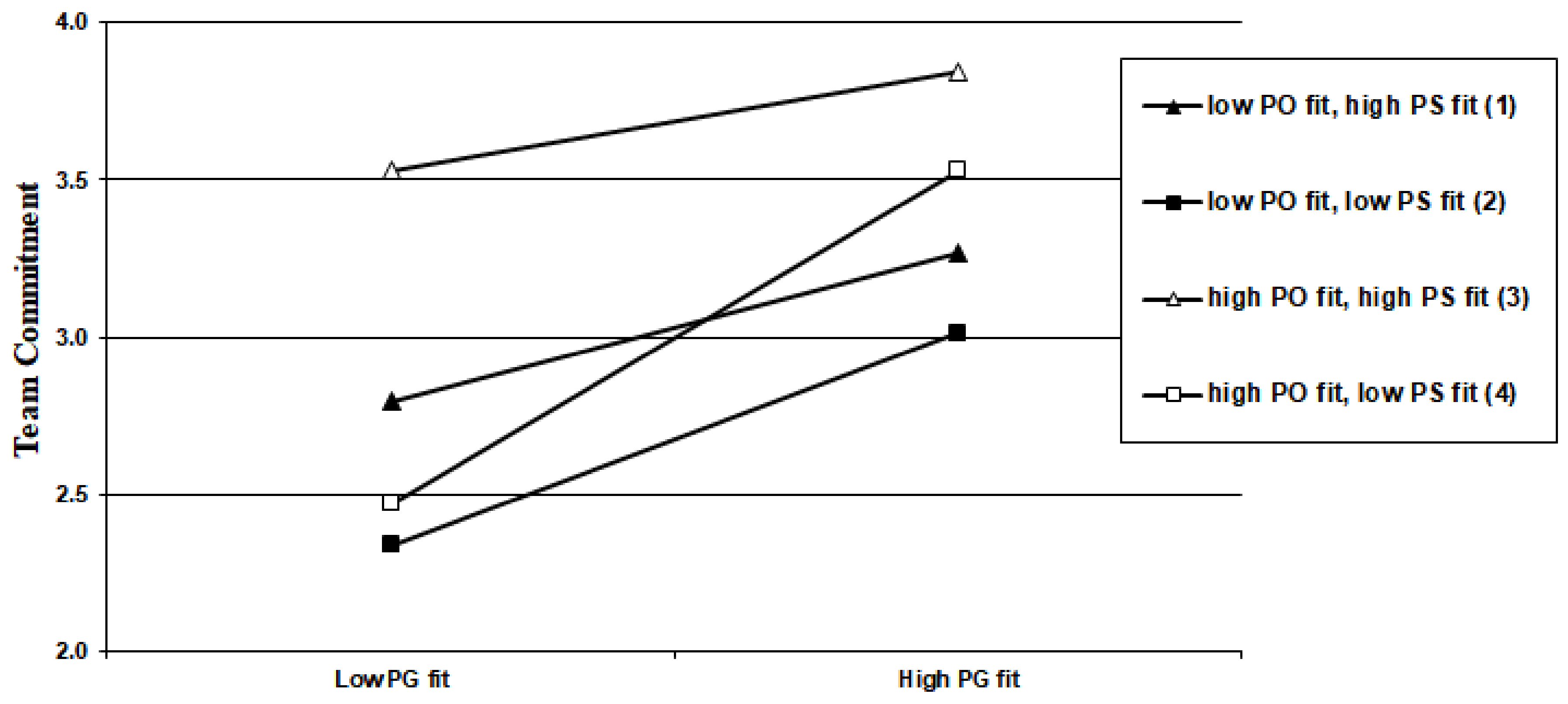

| Slope | b | t |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (Low PO fit, high PS fit) | 0.37 | 2.19 * |

| 2 (Low PO fit, low PS fit) | 0.54 | 4.66 *** |

| 3 (High PO fit, high PS fit) | 0.25 | 2.06 * |

| 4 (High PO fit, low PS fit) | 0.84 | 4.22 *** |

| Slope difference | ||

| (1) and (2) | 0.86 | |

| (1) and (3) | 0.73 | |

| (1) and (4) | 1.61 | |

| (2) and (3) | 1.80 + | |

| (2) and (4) | 1.61 | |

| (3) and (4) | 2.66 ** |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sung, S.H.; Seong, J.Y.; Kim, Y.G. Seeking Sustainable Development in Teams: Towards Improving Team Commitment through Person-Group Fit. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156033

Sung SH, Seong JY, Kim YG. Seeking Sustainable Development in Teams: Towards Improving Team Commitment through Person-Group Fit. Sustainability. 2020; 12(15):6033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156033

Chicago/Turabian StyleSung, Sang Hun, Jee Young Seong, and Yong Geun Kim. 2020. "Seeking Sustainable Development in Teams: Towards Improving Team Commitment through Person-Group Fit" Sustainability 12, no. 15: 6033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156033

APA StyleSung, S. H., Seong, J. Y., & Kim, Y. G. (2020). Seeking Sustainable Development in Teams: Towards Improving Team Commitment through Person-Group Fit. Sustainability, 12(15), 6033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156033