Territorial Management and Governance, Regional Public Policies and their Relationship with Tourism. A Case Study of the Azores Autonomous Region

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Sustainable Development, Tourism, and Insular Regions

- (i)

- Economic—sustainability requires an economic system that matches the interests of its citizens, offers enough employment, and can rejuvenate its population to address these services in the long term [24,25]. To meet those requirements, the competitiveness of the economic system must be part of the concept of sustainability [25]. It can be further extrapolated ahead of this description to include regional and local economic development models, land use and land cover, and real estate markets, among others [26,27,28].

- (ii)

- Social—in general, this pillar refers to public policies that undertake social challenges. Such social problems are related to our collective well-being and prosperity—i.e., healthcare, education, housing, and employment, among many other factors [29]. As part of the social pillar, the institutional dimension must also be addressed. According to Jörg Spangenberg [25]: “Institutions are the success of social interactions, along with established rules over society, by decision-making processes and their tools to apply such policies. Thus, the institutional dimension includes groups from civil society and the policy-makers, from the administrative system, and technicians.” Therefore, from a sustainable development perspective, we should consider public participation, equality of opportunities, no social discrimination, and strong political commitment and transparency.

- (iii)

- Environmental—the environmental dimension is described as the sum of all bio-geological processes along with their elements. Therefore, it demands the conservation and preservation of ecological systems as the natural basis for supporting human society [25,30]. Through well-designed and executed planning strategies, the integration and cooperation between societies and the environment may create several benefits for cities and territories in different contexts. Such synergies support green areas with ecological and cultural heritage value, protecting biodiversity and preventing the formation of heat islands in urban territories, among several other benefits [11,31]. It should also consider the estrangements arising from disparities in planning intentions, such as differing interests of stakeholders, or issues related to the planning of waste management, among many other challenges in rural and urban territories. In fact, those planning problems will be used as incentives to promote economic performance, social equity, and environmental efficiency, instead of sustainable development barriers.

Peripheral and Insular Areas

3. Spatial Planning of Tourism and Sustainability in the Azores Archipelago

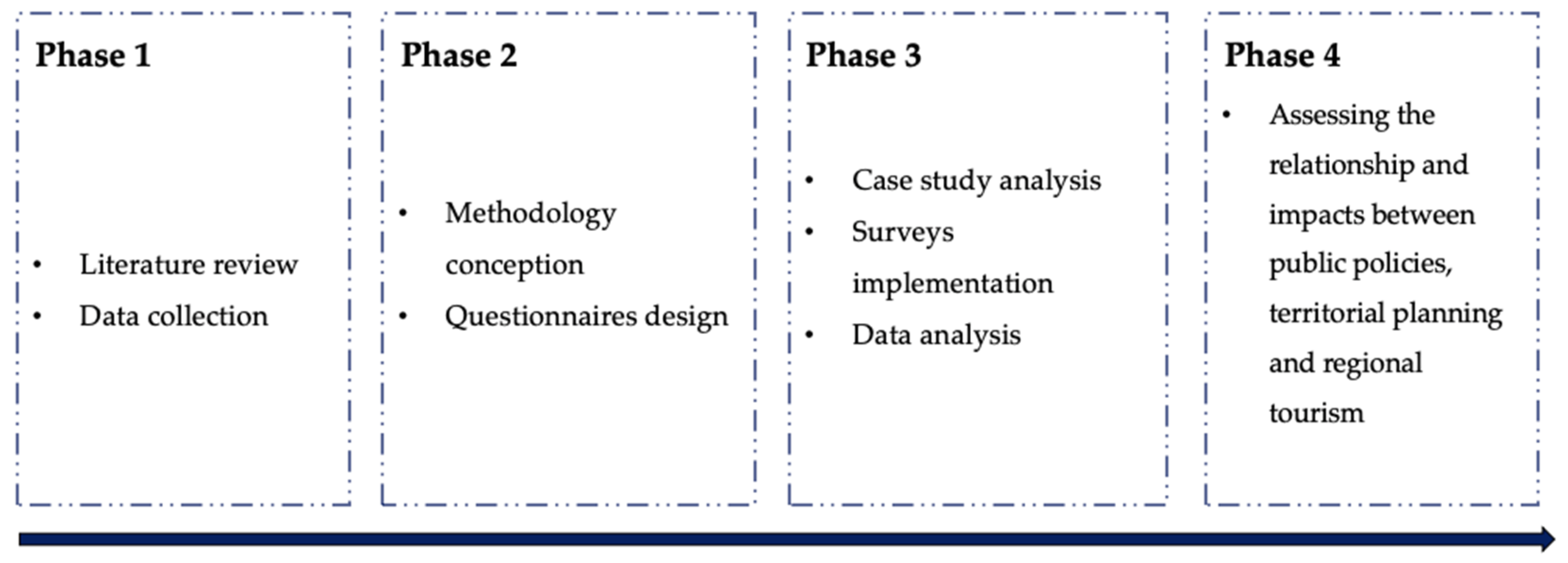

4. Material and Methods

5. Questionnaires and Results

6. Discussions and Conclusions

- design policies that focus on sustainable development, endeavoring to create meaningful investments in infrastructure and services (mainly on accessibility by air);

- promote the conservation and preservation of ecological systems;

- encourage the interaction between societies and the environment;

- support entrepreneurship associated with small and medium-sized businesses (promoting the variety of offering);

- prioritize rural tourism over mass tourism.

7. Study Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marchant, R.; Lane, P. Past perspectives for the future: Foundations for sustainable development in East Africa. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 51, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, M. Planeamento Urbano Sustentável; Caleidoscópio: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009; ISBN 9789728801748. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Lippolis, L. Viaggio al Termine Della Cità—La Metropoli e le Arti Nell′Áutumno PostModerno (1972–2001); Eleuthera: Genova, Italia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, R. O Regresso dos Emigrantes Portugueses e o Desenvolvimento do Turismo em Portugal. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo Gómez, J.M.; Lousada, S.; Velarde, J.G.; Castanho, R.A.; Loures, L. Land-use changes in the canary archipelago using the CORINE data: A retrospective analysis. Land 2020, 9, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J. Towards Sustainable Europe, A Study from the Wuppertal Institute for Friends of the Earth Europe; Russel Press: Luton, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Vulevic, A.; Macura, D.; Djordjevic, D.; Castanho, R. Assessing Accessibility and Transport Infrastructure Inequities in Administrative Units in Serbia´s Danube Corridor Based on Multi-Criteria Analysis and GIS Mapping Tools; Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences; Babes-Bolyai University: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2018; Volume 53, pp. 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadigas, L. Urbanismo e Território, As Políticas Públicas; Edições Sílabo: Lisbon, Portugal, 2015. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Loures, L.; Panagopoulos, T. Reclamation of derelict industrial land in Portugal–greening is not enough. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2010, 5, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loures, L. Post-industrial landscapes as drivers for urban redevelopment: Public versus expert perspectives towards the benefits and barriers of the reuse of post-industrial sites in urban areas. Habitat Int. 2015, 45, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loures, L.; Naranjo Gómez, J.M.; Castanho, R.A.; Loures, A. Benefits and limitations of public involvement processes in landscape redevelopment projects—Learning from practice. In Regional Intelligence Spatial Analysis and Anthropogenic Regional Challenges in the Digital Age; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo, J.M. Impacts on the social cohesion of mainland Spain’s future motorway and high-speed rail networks. Sustainability 2016, 8, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vulevic, A. Infrastructural Corridors and Their Influence on Spatial Development—Example of Corridor VII in Serbia. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Geography, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, R.; Castanho, R.A.; Lousada, S. Return migration and tourism sustainability in portugal: Extracting opportunities for sustainable common planning in southern europe. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jurado Almonte, J.M.; Tristancho, A.F. Experiencias En Turismo Accesible En Andalucía Y Portugal: Especial Atención Al Ámbito Alentejo-Algarve-Provincia De Huelva; Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Huelva: Huelva, Spain, 2016; Volume 182. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, C.; Couto, G.; Pimentel, P.; Vieira, J. Quality of the Azores destination in the perspective of tourists. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 12, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanho, R.A.; Couto, G.; Pimentel, P.M. Principles of sustainable tourism and cultural management in rural and ultra-peripheral territories: Extracting guidelines for its application in the Azores Archipelago. Cult. Manag. Sci. Educ. 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrop, M. Sustainable landscapes: Contradiction, fiction or utopia? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loures, L.; Castanho, R.A.; Vulevic, A.; Naranjo Gómez, J.; Cabezas, J.; Fernández-Pozo, L. The multi-variated effect of city cooperation in land use planning and decision-making processes–a european analysis. In Urban Agglomerations; InTech: Vienna, Austria, 2018; pp. 87–106. ISBN 978-953-51-5884-4. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, M. A Arquitectura Paisagista: Morfologia e Complexidade; Editorial Estampa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vargues, P.; Loures, L. Using geographic information systems in visual and aesthetic analsis: The case study of a golf course in Algarve. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2008, 4, 774–783. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgili, F.; Ulucak, R.; Koçak, E.; İlkay, S. Does globalization matter for environmental sustainability? Empirical investigation for Turkey by Markov regime switching models. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 1087–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faludi, A.; Valk, A. Rule and order dutch planning doctrine in the twentieth century. In The GeoJournal Library; Springer: Heidelberg, The Netherlands, 1994; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. Risikogesellschaft—The Risk Society; BACHELOR MASTER: Frankfurt, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J. Sustainable Development–Concepts and Indicators; Russel Press: Koln, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo Gómez, J.M.; Loures, L.; Castanho, R.A.; Cabezas, J.; Fernández-Pozo, L.; Lousada, S.; Escórcio, P. Assessing Land Use Changes in European Territories: A Retrospective Study from 1990 to 2012; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Codosero Rodas, J.; Cabezas, J.; Naranjo Gómez, J.; Castanho, R.A. Risk premium assessment for the sustainable valuation of urban development land: Evidence from Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Codosero Rodas, J.; Castanho, R.A.; Cabezas, J.; Naranjo Gómez, J. Sustainable valuation of land for development, Adding value with urban planning progress, A Spanish case study. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union (EU). Policy Forum on Development, Working Group: Social Pillar of Sustainable Development. Available online: www.europa.eu (accessed on 11 July 2020).

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Dur, F.; Dizdarogluc, D. Towards prosperous sustainable cities: A multiscalar urban sustainability assessment approach. Habitat Int. 2015, 45, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaletová, T.; Loures, L.; Castanho, R.A.; Aydin, E.; Gama, J.; Loures, A.; Truchy, A. Relevance of Intermittent Rivers and Streams in Agricultural Landscape and Their Impact on Provided Ecosystem Services—A Mediterranean Case Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hui, E.; Bao, H. The logic behind conflicts in land acquisition in contemporary China: A framework based upon game theory. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, S.P. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order; Penguin Books: Haryana, India, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, A.T.W.; Wu, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhang, X.; Shen, L.; Shan, L. The key causes of urban-rural conflict in China. Habitat Int. 2015, 49, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, J.; Castanho, R.A.; Loures, L.; Pinto-Gomes, C.; Santos, P. Villagers’ Perceptions of Tourism Activities in Iona National Park: Locality as a Key Factor in Planning for Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez-Serrano, I.; Caldés, N.; De La Rúa, C.; Lechón, Y.; Garrido, A. Using the Frame-work for Integrated Sustainability Assessment (FISA) to expand the Multiregional Input–Output analysis to account for the three pillars of sustainability. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2017, 19, 1981–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadahunsi, J.T. Application of geographical information system (GIS) technology to tourism management in ile-ife, osun state, nigeria. Pac. J. Sci. Technol. 2011, 12, 274–283. [Google Scholar]

- Labrianidis, L.; Thanassis, K. A Suggested Typology of Rural Areas in Europe. Available online: Cordis.europa.eu (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Sharpley, R.; Vass, A. Tourism, farming and diversification: An attitudinal study. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1040–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. Introduction. In Southern Europe Transformed-Political and Economic Change in Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain; Williams, A., Ed.; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, A.; Felsenstein, D. Support for rural tourism—Does it make a difference? Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 1007–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, H.; Ahmed, M.; Al-Amin, Q. Estimating total contribution of tourism to Malaysia economy. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2009, 2, 146–159. [Google Scholar]

- Reeder, R.; Brown, D. Recreation, Tourism, and Rural Well-Being, Economic Research Report, Number 7; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Castanho, R.A.; Behradfar, A.; Vulevic, A.; Naranjo Gómez, J. Analyzing Transportation Sustainability in the Canary Islands Archipelago. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulevic, A.; Castanho, R.A.; Naranjo Gómez, J.M.; Loures, L.; Cabezas, J.; Fernández-Pozo, L.; Martín Gallardo, J. Accessibility Dynamics and Regional Cross-Border Cooperation (CBC) Perspectives in the Portuguese-Spanish Borderland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kilkenny, M.; Partridge, M. Export Sectors and Rural Development. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2009, 91, 910–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahony, K.; Zyl, J. The impacts of tourism investment on rural communities: Three case studies in South Africa. Dev. S. Afr. 2002, 19, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decreto Legislativo Regional, n.º 38/2008/A. Available online: https://dre.pt/application/conteudo/455635 (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- Silva, F.; Almeida, M. Sustentabilidade do turismo na natureza nos Açores—O caso do canyoning. In Turismo e Desporto Na Natureza; do Céu Almeida, M., Ed.; Associação de Desportos de Aventura Desnível: Estoril, Portugal, 2013; pp. 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, J.; Couto, G.; Pimentel, P.; Menezes, A.; Moniz, A.; Sousa, F. The Satisfaction of the Nordic Tourist with the Azores as a Destination. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2013, 13, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varley, P.; Semple, T. Nordic Slow Adventure: Explorations in Time and Nature. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 15, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varley, P.; Farkic, J.; Carnicelli, S. Hospitality in Wild Places. Hosp. Soc. 2018, 8, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Couto, G.; Pimentel, P.; Ponte, J. Tourism development potential in an insular territory: The case of ribeira grande in the Azores. J. Tour. Res. Hosp. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, G.; Ponte, J.; Pimentel, P.; Sousa, Á.; Oliveira, A. Tourist satisfaction with the Municipality of Ponta Delgada (Azores). Rev. de Gestão e Secr. 2019, 10, 192–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, J.; Couto, G.; Pimentel, P.; Santos, C.; Oliveira, A. Tourism activities and companies in a sustainable adventure tourism destination: The Azores; CEEAplA–Centro de Estudos de Economia Aplicada do Atlântico, Universidade dos Açores, Working Paper; CEEAplA: Ponta Delgada, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Couto, G.; Ponte, J.; Pimentel, P.; Oliveira, A. Tourism activities and companies in a sustainable adventure tourism destination: The Azores. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2018, 14, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, G.; Pimentel, P.; Ponte, J.; Gonçalves, P.; Duarte, D.; Arruda, A.; Oliveira, B.; Rodrigues, F. Açores Guia do Investidor para o Turismo Sustentável/Azores Investor’s Guide to Sustainable Tourism; Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento (FLAD): Lisboa, Portugal, 2018; ISBN 978-972-8654-61-0. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. AM Reports, Volume Nine—Global Report on Adventure Tourism; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2014; Available online: https://bit.ly/2HxnY3z (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Yin, R. Case Study Research Design and Methods, 5th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4522-4256-9. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, M. A Case Study Method for Landscape Architecture; Urban Land Institute, University of California: Davis, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Castanho, R.A.; Lousada, S.; Camacho, R.; Naranjo Gómez, J.; Loures, L.; Cabezas, J. Ordenamento territorial e a sua relação com o turismo regional: O Caso de Estudo da Região Autónoma da Madeira (RAM). CIDADES Comunidades e Territ. 2018, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacelar-Nicolau, H. On the distribution equivalence in cluster analysis. In Pattern Recognition Theory and Applications, NATO ASI Series, Series F: Computer and Systems Sciences; Devijver, P.A., Kittler, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lerman, I.C. Classification et Analyse Ordinale des Données; Dunod: Paris, France, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Lerman, I.C. Foundations and methods in combinatorial and statistical data analysis and clustering. In Series: Advanced Information and Knowledge Processing; Springer: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bacelar-Nicolau, H. Two probabilistic models for classification of variables in frequency tables. In Classification and Related Methods of Data Analysis; Bock, H.-H., Ed.; Elsevier Sciences Publishers B.V.: North-Holland, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolau, F.C.; Bacelar-Nicolau, H. Some trends in the classification of variables. In Data Science, Classification, and Related Methods; Hayashi, C., Ohsumi, N., Yajima, K., Tanaca, Y., Bock, H.-H., Baba, Y., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 1998; pp. 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Couto, G.; Pimentel, P.; Ponte, J. Estratégia de Desenvolvimento Turístico da Ribeira Grande; Universidade dos Açores/Centro de Estudos de Economia Aplicada do Atlântico–CEEAplA: Ponta Delgada, Portugal, 2017; ISBN 978-989-8870-05-6. [Google Scholar]

- Couto, G.; Pimentel, P.; Santos, C.; Ponte, J.; Oliveira, A. Estratégia de Desenvolvimento Turístico de Ponta Delgada; Universidade dos Açores/Centro de Estudos de Economia Aplicada do Atlântico–CEEAplA: Ponta Delgada, Portugal, 2017; ISBN 978-989-8870-08-7. [Google Scholar]

- Couto, G.; Pimentel, P.; Ponte, J.; Gonçalves, P.; Duarte, D.; Arruda, A.; Oliveira, B. Açores na Europa–Impacto dos Fundos Estruturais; Edição Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento (FLAD): Lisboa, Portugal, 2017; ISBN 978-972-8654-60-3. [Google Scholar]

| Award | Organization | Comments | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top 10 Most Sustainable World Destinations | Green Destinations | Best of the Atlantic | 2018 |

| Top 100 Most Sustainable World Destinations | Green Destinations | First place in 2014, with 8.9 points out of 10 | 2018 2017 2016 2014 |

| QualityCoast Platinum Award | QualityCoast—Coastal and Marine Union of the European Union |

| 2017 2014–2016 |

| QualityCoast Gold Award | QualityCoast—Coastal and Marine Union of the European Union | Best Quality Coastal Destination in Europe | 2013 |

| Best of the Best – Nature Award | European Commission | Granted to Project “Life Priolo”, which was developed between 2003 and 2008, focused on the protection and restoring of the risk vegetation of the laurel forest of the Azores | 2010 |

| Second-Best Islands in the World for Sustainable Tourism | National Geographic Traveler | - | 2010 |

| Ospar Convention | OSPAR Commission |

| 2010 |

| Biosphere Reserves | UNESCO |

| 2007 2007 2009 |

| Natura Network 2000 | European Commission |

| 1989 |

| UNESCO World Heritage | UNESCO |

| 1983 2004 |

| Variables | % | Variables | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Field of expertise | ||

| Economic Sciences | 11.9% | ||

| Male | 36.8% | Education | 10.4% |

| Female | 63.2% | Engineering | 2.9% |

| Age Group | Management and Administration | 16.4% | |

| 18–35 | 57.5% | Medical Sciences and Biology | 5.8% |

| 36–50 | 22.6% | Planning | 4.4% |

| + 50 | 19.8% | Social Sciences | 17.9% |

| Resident of the Azores | Tourism | 5.9% | |

| Yes | 92.5% | Others | 23.8% |

| No | 7.5% | ||

| Questions * | Answers % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–35 | 36–50 | +50 | Do not know / Do not answer | |

| A | 10.4% | 51.9% | 34.0% | 3.8% |

| B | 3.8% | 40.6% | 43.4% | 12.3% |

| Questions * | Answers % | ||

| Yes | No | Do not know/Do not answer | |

| a | 99.1% | 0.9% | 0.0% |

| b | 96.2% | 0.9% | 2.8% |

| c | 85.8% | 9.4% | 4.7% |

| d | 84.9% | 2.8% | 12.3% |

| Question ** | Answers % | ||

| Positives | Negatives | Do not know / Do not answer | |

| e | 45.3% | 36.8% | 17.9% |

| Sentences * | Level of Agreement ** % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| i | 0.0% | 6.7% | 41.9% | 39.0% | 12.4% |

| ii | 0.0% | 12.3% | 37.7% | 40.6% | 9.4% |

| iii | 0.0% | 11.3% | 45.3% | 38.7% | 4.7% |

| iv | 2.8% | 9.4% | 42.5% | 39.6% | 5.7% |

| v | 1.9% | 17.0% | 37.7% | 31.1% | 12.3% |

| i | ii | iii | iv | v | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | 0.512 ** | 0.412 ** | 0.444 ** | −0.110 | |

| ii | 1.000 | 0.521 ** | 0.545 ** | −0.025 | |

| iii | 1.000 | 0.555 ** | 0.049 | ||

| iv | 1.000 | 0.137 | |||

| v | 1.000 |

| i | ii | iii | iv | v | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | 1.000000 | 0.993178 | 0.992565 | 0.991502 | 0.980975 |

| ii | 1.000000 | 0.993654 | 0.993040 | 0.981013 | |

| iii | 1.000000 | 0.993396 | 0.983799 | ||

| iv | 1.000000 | 0.982136 | |||

| v | 1.000000 |

| Activities | Answers (%) |

|---|---|

| Accommodation | 54.7% |

| Culture | 15.1% |

| Nature | 51.9% |

| Rental/hire services | 17.9% |

| Restoration | 38.7% |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castanho, R.A.; Couto, G.; Pimentel, P.; Carvalho, C.B.; Sousa, Á. Territorial Management and Governance, Regional Public Policies and their Relationship with Tourism. A Case Study of the Azores Autonomous Region. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6059. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156059

Castanho RA, Couto G, Pimentel P, Carvalho CB, Sousa Á. Territorial Management and Governance, Regional Public Policies and their Relationship with Tourism. A Case Study of the Azores Autonomous Region. Sustainability. 2020; 12(15):6059. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156059

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastanho, Rui Alexandre, Gualter Couto, Pedro Pimentel, Célia Barreto Carvalho, and Áurea Sousa. 2020. "Territorial Management and Governance, Regional Public Policies and their Relationship with Tourism. A Case Study of the Azores Autonomous Region" Sustainability 12, no. 15: 6059. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156059

APA StyleCastanho, R. A., Couto, G., Pimentel, P., Carvalho, C. B., & Sousa, Á. (2020). Territorial Management and Governance, Regional Public Policies and their Relationship with Tourism. A Case Study of the Azores Autonomous Region. Sustainability, 12(15), 6059. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156059