Sustainable Development and European Banks: A Non-Financial Disclosure Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Toward which SDGs is the non-financial reporting activity of European banks oriented?

- What is the contribution of European banks to the SDGs?

- Which contextual factors seem differentiate the contribution of European banks to the SDGs?

2. Literary Review

2.1. SDG Reporting and Banking Sector

2.2. Literary Review on SDGs

- The use of accounting technologies for monitoring the pursuit of the SDGs, both individually and combined together [34];

- The use of social media and big data for the collection and subsequent elaboration of relevant information for the analysis of the SDGs and the implementation of specific performance indicators;

- The importance of a synergy between the various levels of governance (local, domestic, and global) for achieving the goals (among which, in particular, are SDGs 16 and 17), the implementation of which is subordinated to the adoption of a range of instruments [34].

- Empirical studies that seek to identify factors, internal and external, affecting or discriminating the SDG reporting [3].

- Deloitte-SDA Bocconi [10], a report showing that 21% of EIP (198 DNF published within 15 July 2018)—within the scope of the Legislative Decree 254/16—provides SDG reporting mainly on goals 1, 3, and 11.

- GBS [15], a research showing that 17% of EIP (202 DNF published within 31 August 2018) provides SDG reporting. Banks, in particular, in addition to presenting a good level of SDG reporting compared with other sectors, provide quantitatively reliable and more relevant information with regard to goal 8 and higher-quality information as for goals 3, 6, 7, and 14 [15].

3. The Sample

4. Methodology

- Number of reported SDGs (a proxy for social, economic, and environmental breadth of the contribution in terms of sustainable development (although this evaluation complies with a level of discretion, it should be noted that the proxy examined is consistent with the content of the 2030 Agenda, which suggests not only to the subscribers of the agreement, but also to the economic operators involved to commit to as many SDGs as possible, by measuring and monitoring the contributions provided).

- Level of detail in statements (proxy for the commitment and attention paid to the SDGs by banks); for each bank, a score of 0.5 was assigned to generic disclosure and the value 1 to detailed information. The choice of 0.5 instead of 0 (in analogy with what was done previously for the other components of the score) is justified with a purely computational purpose: The score derives from the product of the 4 components considered, one of which is the level of detail of disclosure. In the case of generic disclosure for a bank, assigning the value 0 to it, the score would have been improperly equal to 0 regardless of the value of the other components.

- Number of sections in which the SDGs appear (proxy for the degree of integration of the information concerning the SDGs and attention paid to the SDGs). Six sections were considered for each bank (the letter from the CEO, the materiality analysis, the business model, the strategic plan, stakeholder engagement, and the correlation table SDG-GRI) and, to each of them, a value of 0 was assigned in case of absence and a value of 1 in case of presence of SDGs disclosure.

- Number of stakeholders (proxy for the level of attention to the demands expressed by the stakeholders involved). For each bank, 8 stakeholders were considered (customers, suppliers, employees, lenders, shareholders, institutions, communities, and the environment) assigning to each of them a value of 0 in case of absence or 1 in case of presence in the disclosure.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Priority SDGs for European Banks

5.2. The Contribution of European Banks to the SDGs

5.3. Factors Differentiating the Contribution of Banks to the SDGs

- “Home country” factor and 22 groups of banks (one group per country) have been examined. At the level of significance of 5%, the country is a discriminatory factor in the contribution of banks to the SDGs. The null hypothesis (p-value < 0.05) is rejected: It can be affirmed that the country may differentiate the contribution to the SDGs. Consistently with Jensen and Berg [70] and Vormedal [71], specific attributes of the country of origin are relevant determinants for reporting. The relevance of a link between country and orientation toward the SDGs is confirmed by recent papers, which stress the importance of studies based on a comparison between the policies implemented by each country in pursuing the 17 goals [72]. This result also corroborates the findings obtained from the study by Ike et al. [20], which shows that the influence of the Country System in the reporting on the SDGs also impacts on the prioritization of goals.

- The “legal system” factor and two groups have been examined: The civil law system and common law system. At the level of significance of 5%, the legal system is a discriminatory factor in the contribution of banks to the SDGs. The null hypothesis (p-value < 0.01) is rejected; in the two groups of civil law and common law a significant statistical difference exists between the distributions of scores. The result could confirm the findings found by other studies, which, comparing sustainability disclosure between companies in civil law and common law countries, show the presence of significant statistical differences [73,74,75,76].

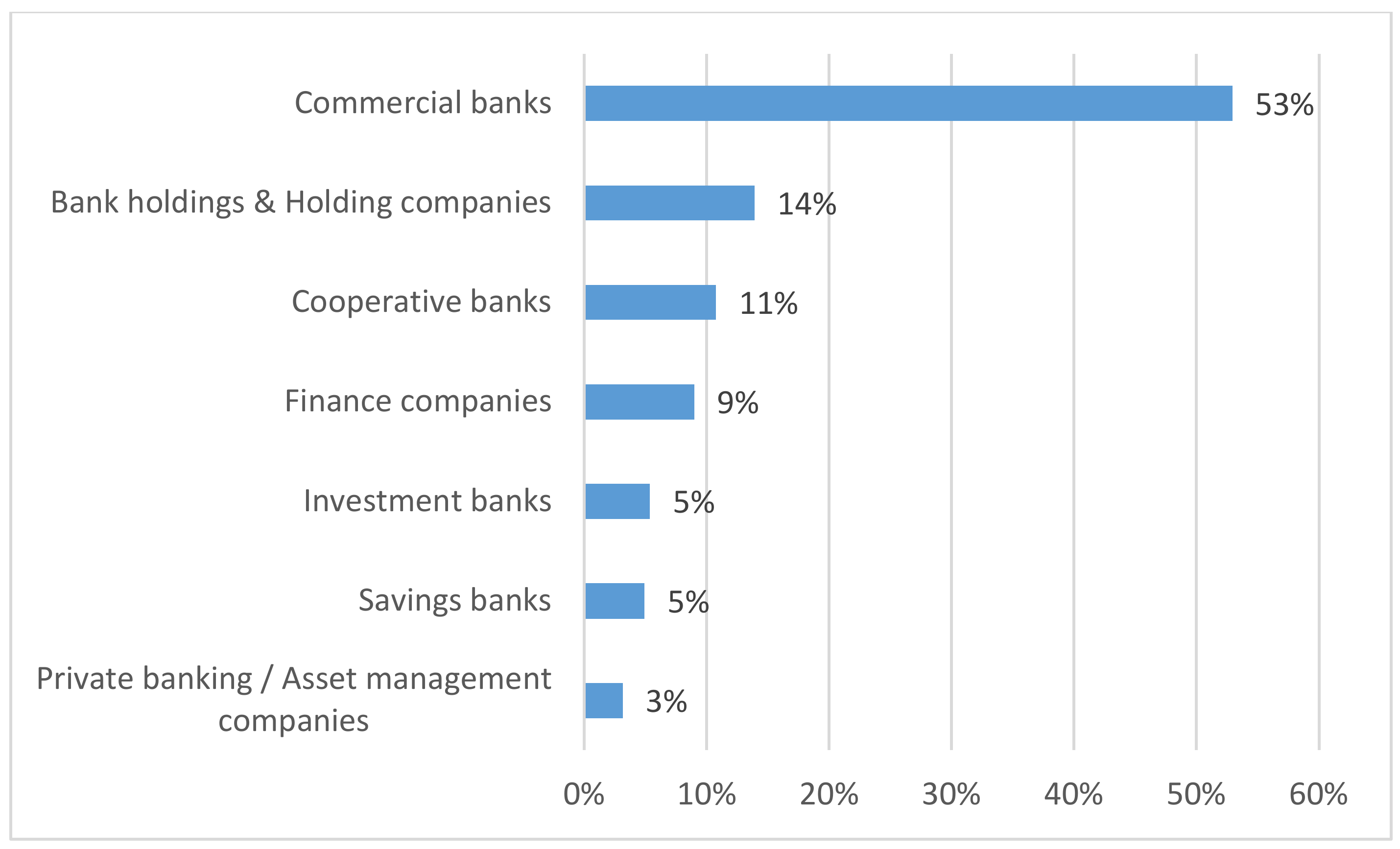

- The “Business model” factor and seven groups of banks (one group per each business model) have been examined. Table 2 indicates that, at the level of significance of 5%, the difference between various bank models shall not be considered discriminatory of the contribution toward the SDGs.

- The “Stock exchange listing” factor and two groups of banks have been examined. The tests indicate that the listing of banks does not seem to represent a discriminatory factor in the orientation toward the SDGs. Consistent with signaling theory and previous literature [77,78,79] on the role of listed firms in driving change, we expected listed banks to have a much broader approach to SDGs than unlisted banks. The results do not confirm expectations.

- The “Integrated report” factor and two groups of banks have been examined. Table 2 shows that, at the level of significance of 5%, the null hypothesis (p-value < 0.01) is rejected: The choice to draw up an integrated report is a discriminatory factor in the contribution to the SDGs. This result is consistent with the findings of the study by Rosati and Faria [3], in which the compliance with a sustainability framework represents an internal discriminatory factor in terms of SDGs reporting.

- 1

- Country of origin;

- 2

- Legal system;

- 3

- Adoption of an integrated report;

6. Conclusions

- There is a substantial uniformity in the prioritization of the SDGs within EU countries and types of bank, also confirmed by a comparison between listed and non-listed banks.

- The “scope” of contribution to SDGs from the European banks is narrow. It is higher in emerging countries such as Estonia, Croatia, and Poland with significant differences in comparing banks operating in the same country.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pillai, K.V.; Slutsky, P.; Wolf, K.; Duthler, G.; Stever, I. Companies’ Accountability in Sustainability: A Comparative Analysis of SDGs in Five Countries. In Sustainable Development Goals in the Asian Context; Servaes, J., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 85–106. ISBN 978-981-10-2815-1. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, N.; Gneiting, U.; Mhlanga, R. Raising the bar: Rethinking the role of business in the Sustainable Development Goals; Oxfam Discussion Papers; Oxfam: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosati, F.; Faria, L.G.D. Business contribution to the Sustainable Development Agenda: Organizational factors related to early adoption of SDG reporting. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures. Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures i Letter from Michael R. Bloomberg; TFCD: Basel, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- EU Commission. Directive 2014/95/eu of the European Parliament and of the Council-of 22 October 2014-Amending Directive 2013/34/EU as Regards Disclosure of Non-Financial and Diversity Information by Certain Large Undertakings and Groups; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Storey, M.; Killian, S.; O’Regan, P. Responsible management education: Mapping the field in the context of the SDGs. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leadership Council of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network. Indicators and a Monitoring Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals. Launching a Data Revolution for the SDGs; SDSN: Paris, France, 2015; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Global Compact. United Nations Global Compact Progress Report: Business Solutions to Sustainable Development; UN Global Compact: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. 99. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. The Word Bank-Annual Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte-SDA Bocconi. Osservatorio Nazionale sulla Rendicontazione non Finanziaria ex D. Lgs. 254/2016; Report; Deloitte: Milan, Italy, 2018; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- United States Council for International Business. Leveraging the Business Sector for a Sustainable Future. Achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals through Corporate Sustainability; USCIB: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler. How to Report on the SDGs What Good Looks Like and Why it Matters; KPMG International: Amstelveen, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers. SDG Reporting Challenge 2017: Exploring Business Communication on the Global Goals; Annual Report; PwC: London, UK, 2017; 40p. [Google Scholar]

- Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler. The Road Ahead: KPMG International Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting; KPMG International: Amstelveen, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 8, pp. 792–793. [Google Scholar]

- Gruppo di Studio per il Bilancio Sociale. The SDGs in the Reports of the Italian Companies; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2019; p. 156. ISBN 9788891797537. [Google Scholar]

- Donald, K.; Way, S. Accountability for the Sustainable Development Goals: A Lost Opportunity? Ethics & International Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- World Business Council for Sustainable Development. Striking the Balance Sustainable Development Reporting; WBCS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Weitz, N.; Carlsen, H.; Nilsson, M.; Skånberg, K. Towards systemic and contextual priority setting for implementing the 2030 agenda. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Zanten, J.A.; van Tulder, R. Multinational enterprises and the Sustainable Development Goals: An institutional approach to corporate engagement. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2018, 1, 208–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ike, M.; Donovan, J.D.; Topple, C.; Masli, E.K. The process of selecting and prioritising corporate sustainability issues: Insights for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.; Shigetomi, Y. Developing national frameworks for inclusive sustainable development incorporating lifestyle factor importance. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 200, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.; Parker, L.D.; Dumay, J.; Milne, M.J. What counts for quality in interdisciplinary accounting research in the next decade: A critical review and reflection. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2019, 32, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bebbington, J.; Unerman, J. Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: An enabling role for accounting research. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S. Linking Environmental Management Accounting: A Reflection on (Missing) Links to Sustainability and Planetary Boundaries. Soc. Environ. Account. J. 2018, 38, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, S.; Venturelli, A.; Caputo, F. The “comply-or-explain” principle in directive 95/2014/EU. A rhetorical analysis of Italian PIEs. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2020. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D. From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. Lancet 2012, 379, 2206–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, J.; Frost, G.; Beck, C. Material legitimacy: Blending organisational and stakeholder concerns through non-financial information disclosures. J. Account. Organ. Change 2015, 11, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C. Introduction: The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures—A theoretical foundation. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Aibar-Guzmán, B.; Aibar-Guzmán, C.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L. “Sell” recommendations by analysts in response to business communication strategies concerning the Sustainable Development Goals and the SDG compass. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, K. Future perspectives: Doing good but avoiding SDG-washing Creating relevant societal value without causing harm. In OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises: A Glass Half Full; OECD: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Tsalis, T.A.; Malamateniou, K.E.; Koulouriotis, D.; Nikolaou, I.E. New challenges for corporate sustainability reporting: United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for sustainable development and the sustainable development goals. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1617–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrampou, A.; Skouloudis, A.; Iliopoulos, G.; Khan, N. Advancing the Sustainable Development Goals: Evidence from leading European banks. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifácio Neto, J.; Branco, M.C. Controversial sectors in banks’ sustainability reporting. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 26, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Ahmed, F.; Singh, R.K.; Sinha, P. Determination of hierarchical relationships among sustainable development goals using interpretive structural modeling. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 20, 2119–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unerman, J.; Chapman, C. Academic Contributions to Enhancing Accounting for Sustainable Development. Account. Organ. Soc. 2014, 39, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.; Power, D.; Stevenson, L.; Collison, D. Shareholder protection, income inequality and social health: A proposed research agenda. Account. Forum 2017, 41, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Annan-Diab, F.; Molinari, C. Interdisciplinarity: Practical approach to advancing education for sustainability and for the Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R. Is accounting for sustainability actually accounting for sustainability…and how would we know? An exploration of narratives of organisations and the planet. Account. Organ. Soc. 2010, 35, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneva, J.M.; Archel, P.; Correa, C. GRI and the camouflaging of corporate unsustainability. Account. Forum 2006, 30, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouf, D.; Boiral, O. The quality of sustainability reports and impression management: A stakeholder perspective. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2017, 30, 643–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.; Shrives, P.; Marston, C. Voluntary disclosure of accounting ratios in the UK. Br. Account. Rev. 2002, 34, 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Blanc, D. Towards Integration at Last? The Sustainable Development Goals as a Network of Targets. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moggi, S.; Bonomi, S.; Ricciardi, F. Against food waste: CSR for the social and environmental impact through a network-based organizational model. Sustainability 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Griggs, D.; Nilsson, M.; Stevance, A.; McCollum, D. A Guide To SDG Interactions: From Science; International Council for Science: Paris, France, 2017; pp. 1–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M.; Nilsson, M.; Raworth, K.; Bakker, P.; Berkhout, F.; de Boer, Y.; Rockström, J.; Ludwig, K.; Kok, M. Beyond cockpit-ism: Four insights to enhance the transformative potential of the sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1651–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gunawan, J.; Permatasari, P.; Tilt, C. Sustainable development goal disclosures: Do they support responsible consumption and production? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 118989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, F.; Faria, L.G.D. Addressing the SDGs in sustainability reports: The relationship with institutional factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, M.F.; Ciaburri, M.; Tiscini, R. The challenge of sustainable development goal reporting: The first evidence from italian listed companies. Sustainability 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kourula, A.; Pisani, N.; Kolk, A. Corporate sustainability and inclusive development: Highlights from international business and management research. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 24, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ranängen, H.; Cöster, M.; Isaksson, R.; Garvare, R. From global goals and planetary boundaries to public governance-A framework for prioritizing organizational sustainability activities. Sustainability 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ernst & Young. How Do You Fund a Sustainable Tomorrow? EY: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mhlanga, R.; Gneiting, U.; Agarwal, N. Walking the Talk; Oxfam Discussion Papers; Oxfam: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hák, T.; Janoušková, S.; Moldan, B. Sustainable Development Goals: A need for relevant indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 60, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Kühnen, M. Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. A holistic perspective on corporate sustainability drivers. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A. The Sustainable Development Goals, Integrated Thinking and the Integrated Report; IIRC and ICAS: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-909883-41-3. [Google Scholar]

- Biermann, F.; Kanie, N.; Kim, R.E. Global governance by goal-setting: The novel approach of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26–27, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Guidelines on Reporting Climate-Related Information; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; 44p. [Google Scholar]

- Consob. Documento di Consultazione 21 Luglio 2017-Disposizioni Attuative del decreto legislativo 30 Dicembre 2016, n.254 Relativo Alla Comunicazione di Informazioni di Carattere non Finanziario; Consob: Rome, Italy, 2017; pp. 3–4.

- Global Reporting Initiative; CSR Europe. Member State Implementation of Directive 2014/95/EU: A comprehensive overview of how Member States are implementing the EU Directive on Non-financial and Diversity Information; CSR Europe and GRI: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis, 4th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- GRI; UN Global Compact; WBSCD. Linking the SDGs and GRI; Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Beattie, V.; McInnes, B.; Fearnley, S. A methodology for analysing and evaluating narratives in annual reports: A comprehensive descriptive profile and metrics for disclosure quality attributes. Account. Forum 2004, 28, 205–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beck, A.C.; Campbell, D.; Shrives, P.J. Content analysis in environmental reporting research: Enrichment and rehearsal of the method in a British-German context. Br. Account. Rev. 2010, 42, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfaya, A.; Whittington, M. Does designing environmental sustainability disclosure quality measures make a difference? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 28, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopizzi, R.; Iazzi, A.; Venturelli, A.; Principale, S. Nonfinancial risk disclosure: The “state of the art” of Italian companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, M.D.; Jenkins, J.G. The influence of firm performance and (level of) assurance on the believability of management’s environmental report. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2020. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, O.N.; Adebisi, F.A.; Opara, M.; Okafor, C.B. Deployment of whistleblowing as an accountability mechanism to curb corruption and fraud in a developing democracy. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat; European Commission. Sustainable Development in the European Union-Monitoring Report On Progress Towards the Sdgs in An Eu Context; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Volume 2001, ISBN 9789279887451. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, J.C.; Berg, N. Determinants of Traditional Sustainability Reporting Versus Integrated Reporting. An Institutionalist Approach. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2012, 21, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vormedal, I.H.; Ruud, A. Sustainability reporting in Norway—An assessment of performance in the context of legal demands and socio-political drivers. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2009, 18, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusmão Caiado, R.G.; Leal Filho, W.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; de Mattos Nascimento, D.L.; Ávila, L.V. A literature-based review on potentials and constraints in the implementation of the sustainable development goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 1276–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, K.A.; Cahan, S.F.; Sun, J. The effect of globalization and legal environment on voluntary disclosure. Int. J. Account. 2008, 43, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frías-Aceituno, J.V.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L.; García-Sánchez, I.M. Is integrated reporting determined by a country’s legal system? An exploratory study. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 44, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mio, C.; Venturelli, A. Non-financial Information About Sustainable Development and Environmental Policy in the Annual Reports of Listed Companies: Evidence from Italy and the UK. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturelli, A.; Caputo, F.; Leopizzi, R.; Pizzi, S. The state of art of corporate social disclosure before the introduction of non-financial reporting directive: A cross country analysis. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, D.; Gao, Y. How industry peers improve your sustainable development? The role of listed firms in environmental strategies. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2018, 27, 1313–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.X.; Xu, X.D.; Yin, H.T.; Tam, C.M. Factors that Drive Chinese Listed Companies in Voluntary Disclosure of Environmental Information. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Li, W.; Lu, X. Government engagement, environmental policy, and environmental performance: Evidence from the most polluting chinese listed firms. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2015, 24, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Volume 53. [Google Scholar]

- La Torre, M.; Sabelfeld, S.; Blomkvist, M.; Tarquinio, L.; Dumay, J. Harmonising non-financial reporting regulation in Europe: Practical forces and projections for future research. Meditari Account. Res. 2018, 26, 598–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative. Linking the SDGs and the GRI Standards; Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, C.; Metternicht, G.; Wiedmann, T. Initial progress in implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A review of evidence from countries. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1453–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Business Model | Most Reported SDGs | Least Reported SDGs |

|---|---|---|

| Bank holdings & Holding companies | SDG 8 | SDG 14 |

| Commercial banks | SDG 8 | SDG 14 |

| Cooperative banks | SDG 16 | SDG 17 |

| Finance companies | SDG 13 | SDG 14, SDG 15 |

| Investment banks | SDG 7 | SDG 6 |

| Private banking/Asset management companies | SDG 13, 7 | SDG 14, 15, 16, 17 |

| Savings banks | SDG 8, 13 | SDG 6 |

| EU Country | Average Number of SDGs for Bank by Country |

|---|---|

| Denmark | 4 |

| Finland | 6 |

| Norway | 7 |

| Cyprus | 7 |

| Ireland | 7 |

| Sweden | 7 |

| Greece | 8 |

| Belgium | 8 |

| Luxembourg | 8 |

| Italy | 8 |

| Portugal | 9 |

| Germany | 9 |

| Spain | 10 |

| Estonia | 10 |

| UK | 10 |

| Romania | 10 |

| Holland | 10 |

| Hungary | 11 |

| Croatia | 11 |

| Austria | 11 |

| France | 12 |

| Poland | 13 |

| Business Model | Mean of Score | Dev Standard of Score | Max Score | Min Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bank holdings & Holding companies | 5.0 | 4.4 | 14.7 | 0.5 |

| Commercial banks | 7.2 | 7.9 | 43.8 | 0.5 |

| Cooperative banks | 7.4 | 5.4 | 14.7 | 0.2 |

| Finance companies | 8.8 | 7.7 | 21.9 | 1.1 |

| Investment banks | 4.9 | 3.9 | 10.3 | 0.2 |

| Private banking/Asset management companies | 2.5 | 1.9 | 5.9 | 0.2 |

| Savings banks | 8.3 | 6.1 | 20.2 | 1.5 |

| Stock Exchange Listing | Mean of Score | Dev Standard of Score | Max Score | Min Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not listed | 7.1 | 6.9 | 43.8 | 0.2 |

| Listed | 6.4 | 7.0 | 43.8 | 0.4 |

| Integrated Reporting | Mean of Score | Dev Standard of Score | Max Score | Min Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No itegrated report | 6.7 | 7.1 | 43.8 | 0.2 |

| Integrated report | 8.4 | 5.5 | 20.6 | 3.7 |

| Grouping Variable | Test | Sig. |

|---|---|---|

| Country | Independent samples Kruskal-Wallis Test | 0.037 ** |

| Legal system | Independent samples Mann Whitney U Test | 0.007 *** |

| Business model | Indipendent samples Kruskal-Wallis Test | 0.137 |

| Stock exchange listing | Independent samples Mann Whitney U Test | 0.454 |

| Report type (integrated or not) | Independent samples Mann Whitney U Test | 0.007 *** |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cosma, S.; Venturelli, A.; Schwizer, P.; Boscia, V. Sustainable Development and European Banks: A Non-Financial Disclosure Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6146. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156146

Cosma S, Venturelli A, Schwizer P, Boscia V. Sustainable Development and European Banks: A Non-Financial Disclosure Analysis. Sustainability. 2020; 12(15):6146. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156146

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosma, Simona, Andrea Venturelli, Paola Schwizer, and Vittorio Boscia. 2020. "Sustainable Development and European Banks: A Non-Financial Disclosure Analysis" Sustainability 12, no. 15: 6146. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156146

APA StyleCosma, S., Venturelli, A., Schwizer, P., & Boscia, V. (2020). Sustainable Development and European Banks: A Non-Financial Disclosure Analysis. Sustainability, 12(15), 6146. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156146