3.1. The Environmental Crisis

Environmental pollution has been present for several decades, and part of the population has become accustomed to this fact, treating it as an immanent part of our existence on earth. Due to their actions focused mainly on living comfort and economic benefits, people have transformed 2/3 of their ecosystems for their needs [

2]. For several years now, we have been experiencing the effects of the global environmental and climatic crisis more and more acutely. One of the causes of the environmental crisis is the still high emission of carbon dioxide CO

2 into the atmosphere, as a by-product of industry and electricity production. Let the data speak for itself. After rapid global growth of almost 40% in the first decade of the 21st century from 22 to 30 gigatonnes (GT), the second decade brings a flattened growth rate of about 33 GT on average, according to the latest report published in 2019 by the International Energy Agency [

3]. An extremely important element of this data is the visible decrease in CO

2 emissions in high-economy countries, which confirms the rightness of their development strategies based on respect for the environment by introducing elements of a sustainable economy in which land resources are not exploited faster than nature renews them. This applies mainly to industries related to fossil fuel-based power generation but also the construction industry. What is worrying, however, is the continuing increase in CO

2 emissions in less affluent countries, which rose from 10.5 GT CO

2 to 22 GT CO

2 from 2010 to 2019, sending a clear signal to rich societies and international organisations that, in the face of the environmental crisis, only joint action is the most rational and effective direction. Unfortunately, it meets with resistance, resulting from the need to invest in new expensive technologies, which slows down the process of enrichment of communities in poorer countries. The largest contributor to carbon dioxide emissions in the world is the construction industry. In total, buildings and construction account for 39% of total carbon emissions (World Green Building Council (WGBC)) [

4]. Emissions from the energy used to heat and cool buildings account for 28%. The remaining 11% of carbon dioxide emissions come from building processes throughout the life cycle of a building—construction, alteration, renovation (WGBC). Therefore, the promotion of the development and use of low-carbon construction materials and services, the energy efficiency of construction machinery, and the use of renewable energy have been identified as the three main potential ways to reduce carbon emissions in the construction sector [

5].

The promotion of activities in harmony with nature and ecology was formalised in 1987; the term ‘sustainable development’ was first introduced in the report titled “Our Common Future,” created by the World Commission on Environment and Development. It was this committee that convened the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. It is difficult to quote here all the documents adopted at that time that relate to climate protection, biodiversity, or forest protection and use, but also sustainable urban development. Dozens if not hundreds of major international conferences on sustainable urban design have been held around the world. It has been three decades of action with very little effect, because all these years, the world’s most important decision-makers have not wanted to hear about the problems ahead of us by not respecting basic standards of environmental protection and ecology. The threats have been ignored for the benefit of global consumerism. Environmental consciousness emerged at the beginning of the 21st century when human activity led to irreversible changes on earth. One example of positive developments is China and its economic policy, which in recent years has taken a clear course towards sustainable development. However, it did not look so optimistic until several years ago. In terms of GDP size, China became the second-largest economy in the world at the beginning of the century. A poor country gave birth to an economic tiger that everyone has to reckon with. Everyone also wanted to cooperate, hoping for concrete profits. At that time, the Chinese built en masse, changed cities, built new ones. In 2012, it was typical brick construction with a monolithic or prefabricated structure, meeting the requirements of current regulations and standards; that year The Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of China (MOHURD) announced an ambitious plan for sustainable construction at a level of 24% in 2020; in 2017, the targets have been revised by 2020. The new green building area across the country is expected to reach 2 billion square metres, or almost 50% of all residential and commercial investments completed in the year (

Figure 1).

Regrettably, the visual change of cities took place to the detriment of their own identity. An example is Beijing, where historic low-rise residential buildings were demolished, replaced by multi-family buildings, sometimes several or several dozen floors high. No lessons have been learned from earlier demolitions, from the cultural revolution that abandoned the history and tradition of housing construction, in particular, which had lasted continuously for 800 years [

6]. Sustainable development of cities is also non-material elements with a high emotional load, such as historical and cultural continuity, shaping our identity. Today, many companies producing building materials and technical equipment for sustainable, green, and passive buildings have their headquarters and production facilities in China. This includes cladding systems, glazing, heating and cooling of buildings, finishing materials and furniture, but also computers, servers, various types of control panels responsible for the operation of systems optimizing energy consumption and living comfort in buildings. There are also photovoltaic panels, wind turbines, and several other elements important for green architecture certification. Ironically, the country’s economy is still the most energy-intensive of all countries in the world, and China is very reluctant to change its industrial pollution limits under pressure from other countries. The threats to a growth-oriented society—as China has experienced over the years—are primarily environmental and sociocultural ones. Environmental threats generate costs as a result of greenhouse gas emissions, environmental degradation, increasing use of non-renewable resources, abuse of renewable resources, and increased emissions of harmful substances and noise [

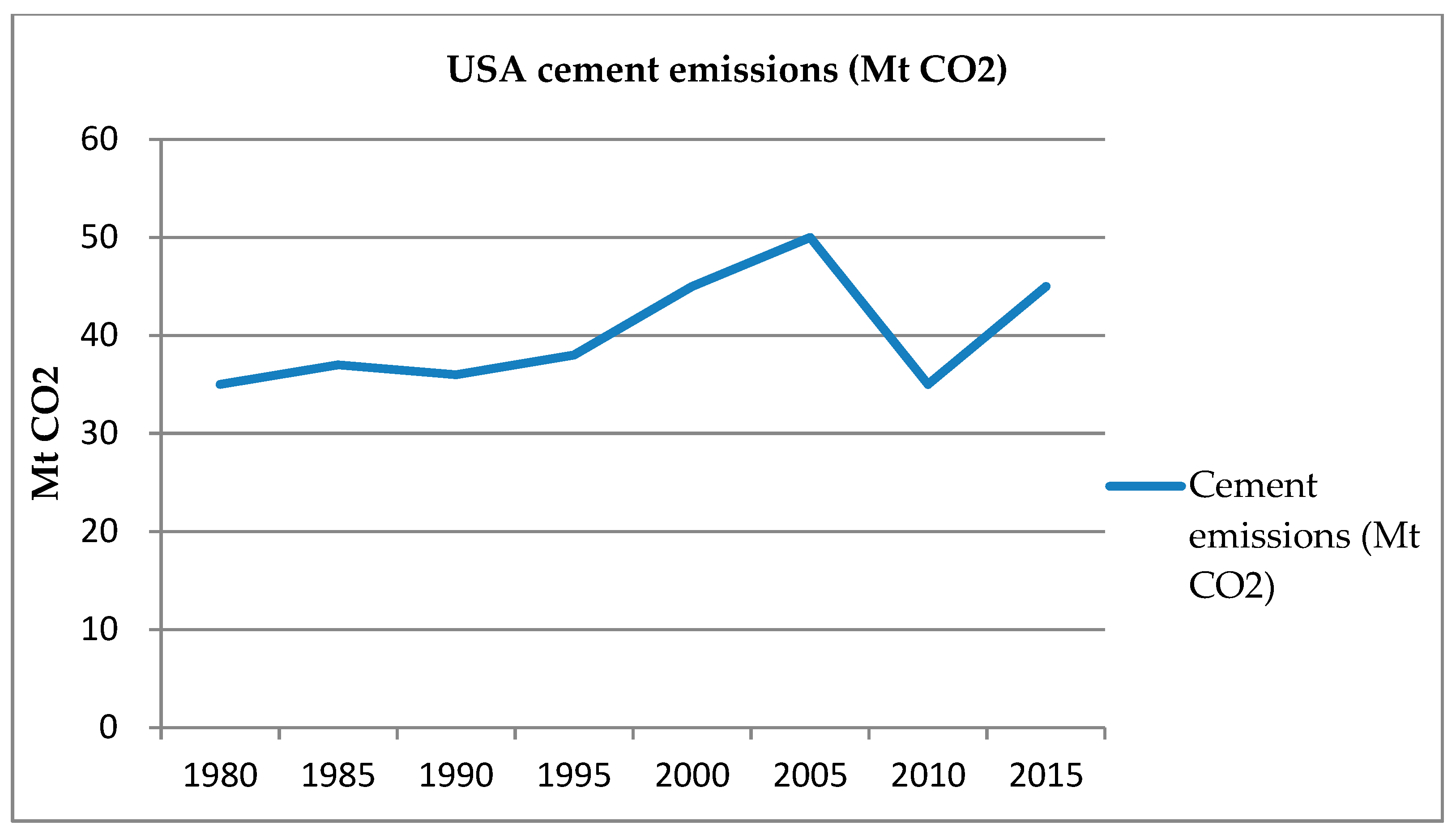

7]. This is illustrated by the diagram of CO

2 emissions from cement production. In 2015, the emissions reached 1.2 billion tonnes per year—as compared to “only” 45 million tonnes in the U.S. at the same time. The graph also shows that the peak growth in emissions occurred during the financial crisis that started in the USA in 2007 (

Figure 2) [

8].

China has been growing rapidly for a long time, regardless of the cost to the surrounding nature. This has resulted in a huge increase in air, water, and soil pollution, which threatens human health and life. Research carried out by the World Bank, the World Health Organization, and the Chinese Academy of Environmental Planning said that environmental pollution in China is responsible for the premature death of between 350,000 and 500,000 people [

7]. However, there came a time when it became clear that this model was no longer sustainable and new mechanisms of development solutions had to be developed which would also take into account environmental protection [

7]. In China, the acquisition of modern technology was mainly due to the inflow of foreign direct investment and the related flow of knowledge. Since the 1980s, the country has pursued a deliberate policy ensuring that foreign corporations have access to its market in exchange for advanced technologies [

9]. The cheap labour force, access to raw materials (oil, iron ore, non-ferrous metal ores, raw materials for fertilizer production) and the prospect of high profits have been the mainstay of Western capital for many years. However, rising production costs over time have resulted in the relocation of production to other countries of the Asian continent mainly. Some industries, primarily those related to new technologies, have remained, not always acting ethically. China is now the largest producer of various types of batteries for the electronics industry as well as batteries for electric cars, the most important element of sustainable urban development—zero-emission transportation. Cobalt is used in their production. However, the most popular electronics manufacturers such as Apple, Samsung, and Sony, manufacturers of electric cars, including Volkswagen, General Motors, Fiat, and Chrysler, have not been interested in the way cobalt used in their devices and cars is obtained for many years. According to a report by Amnesty International (2016) and AfreWatch, which deals with working conditions in cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where the largest supplies of this raw material come from, there are tens of thousands of children working in the mines with many as young as 7-year-olds among them [

10]. After the report, some companies have responded appropriately, increasing monitoring of cobalt supplies; some like Microsoft did not react at all. To think about a sustainable living environment, environmental and even, as described above, ethical measures are of fundamental importance. We have less and less space for a healthy life every year. In 2019, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated that as much as 91% of the world’s population live in areas where poor air quality threatens life and health [

11].

3.2. 2007. Financial Crisis

The environmental crisis has been growing for years; living with it has limited our vigilance in predicting the consequences. The financial crisis is different, with its severe negative economic and social consequences, felt by the majority of citizens of the country affected by the crisis. An event of global significance was the financial crisis which began in the USA with the collapse of subprime loans to citizens to purchase real estate [

12]. The spectacular collapse of Lehman Brothers Bank has only completed the formalities, spreading the financial crisis and, consequently, the economic crisis to virtually all countries of the world. In the USA alone, more than 8.7 million people lost their jobs, especially in male-dominated industries such as construction and manufacturing. The recession lasted three years [

13]. The chart below shows the scale of the market collapse in the long run with the example of traditional single-family house construction in the U.S., and the optimistic trend of green construction (

Figure 3) [

14]. The recovery from the crisis has positioned these two types of single-family buildings in completely different proportions. An authoritative report by Smart Market: National Green of Home Builders -NAHB: Green Multifamily and Single-Family Homes 2017, indicates that, although the share of green single-family houses was only 2% in 2005, it rose to 33% in 2017. It was expected to rise to 38% in 2019 and continue to rise to 44% by 2022 [

15].

It can be assumed that it was the financial crisis that drew the attention of hundreds of thousands of Americans to a more rational way of investing in their homes, making them not only greener, but also cheaper in their later exploitation, and that is sustainable construction.

Although the above optimistic example of a change in the social attitude towards the construction of single-family houses is not a reflection of the global processes of change that took place after 2007, it is a harbinger of correct actions taking into account the ecological and economic aspect, which Rutkowska-Podolska wrote about in 2016.

However, the economic crisis hinders solving the world’s environmental problems and exacerbates the environmental crisis, which in turn further increases the total losses caused by the economic and financial crisis. This creates a feedback effect that is dangerous for the economy. Therefore, to maximise the quality of life and minimise human pressure on the planet, it is important to consider economic, ecological, and sociocultural aspects [

16]. Unfortunately, during the recovery from the economic crisis, part of the economy is focused on improving macroeconomic indicators as soon as possible, the aim being to reach pre-crisis levels as a rebound point. Under these circumstances, is caring for the environment an encouraging factor? Unfortunately, the answer is no. The graph below shows the CO

2 emissions of the cement industry in the U.S. during the years of the financial crisis (

Figure 4) [

8].

The visible slump is typical for most of the world’s cement producers outside China, as already noted (

Figure 2). In those years, China competed with its goods on the world markets mainly through price, so it can be presumed that the global construction industry relied on a Chinese product to save money when recovering from the crisis. The product paid for came with a high mortality rate due to environmental pollution and underestimated emission standards of harmful factors into the atmosphere. Even the greenest buildings, certified office buildings, residential buildings, schools, trade, etc., completed at that time raise ethical concerns once again. Since 2014, when the crisis and its consequences became averted, sales of Chinese cement have been steadily decreasing and will reach 2.14 million tonnes in 2020 [

17]. Given the current state of the world caused by the coronavirus, there are already many warnings in the Western media about China’s renewed domination after the crisis. The mechanism of action may be the same as described above. The consequence of civilization is man’s drive for profit at all costs and a lack of sensitivity to nature, which in turn has led to an ecological crisis [

16].

3.3. Covid-19 Humanitarian Crisis

The date of November 17, 2019, will be recorded in history books all over the world. It was on that day that a 55-year-old man, described after a time as patient “0,” became infected with the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. By the end of December, there were already 60 patients, but the worst was to come a little later. Within only 5 months, the virus attacked all over the world. By the end of May 2020, there were already more than 5 million people sick and over 328,000 confirmed deaths due to the infection. Currently, there is no country where its health care system can control the virus because there is not yet an effective cure to fight the infection while for procedural reasons of laboratory testing, an effective vaccine may not be effective until next year. The only effective protection against infection is isolation from the environment in which there may be other people. This is what has happened, those who can work remotely, work from home, those who cannot, like a whole host of services that look after our safety and health, do it with personal protective equipment (PPE). Organisational prevention and protection measures were developed and implemented to minimise the likelihood of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 [

18]. Some companies have discontinued their operations. Some branches of the economy are going bankrupt or will go bankrupt in the foreseeable future; the whole tourist and hotel sector, land and air transport are going into decline [

19]. At the end of March, just at the beginning of the pandemic, stock exchanges around the world were reaching levels not seen for 30 years, the main index on Wall Street on March 17 alone lost over 12%. The crisis caused by the coronavirus has already put 38.6 million Americans in line for benefits, i.e., one in five citizens has lost their jobs. At the end of April, unemployment in the U.S. was 14%, and it could actually be much higher. On May 5, Reuters published Federal Reserve FED calculations according to the new U-Cov unemployment rate, its value exceeds 30%. All over the world, where COVID-19 appeared, as this is the official name of the coronavirus announced by the World Health Organization, the economic situation looks similar or hardly better. The European data does not show such a drastic desolation of the labour markets in individual countries. The unemployment rate is mostly below 10% with Spain leading with 14% [

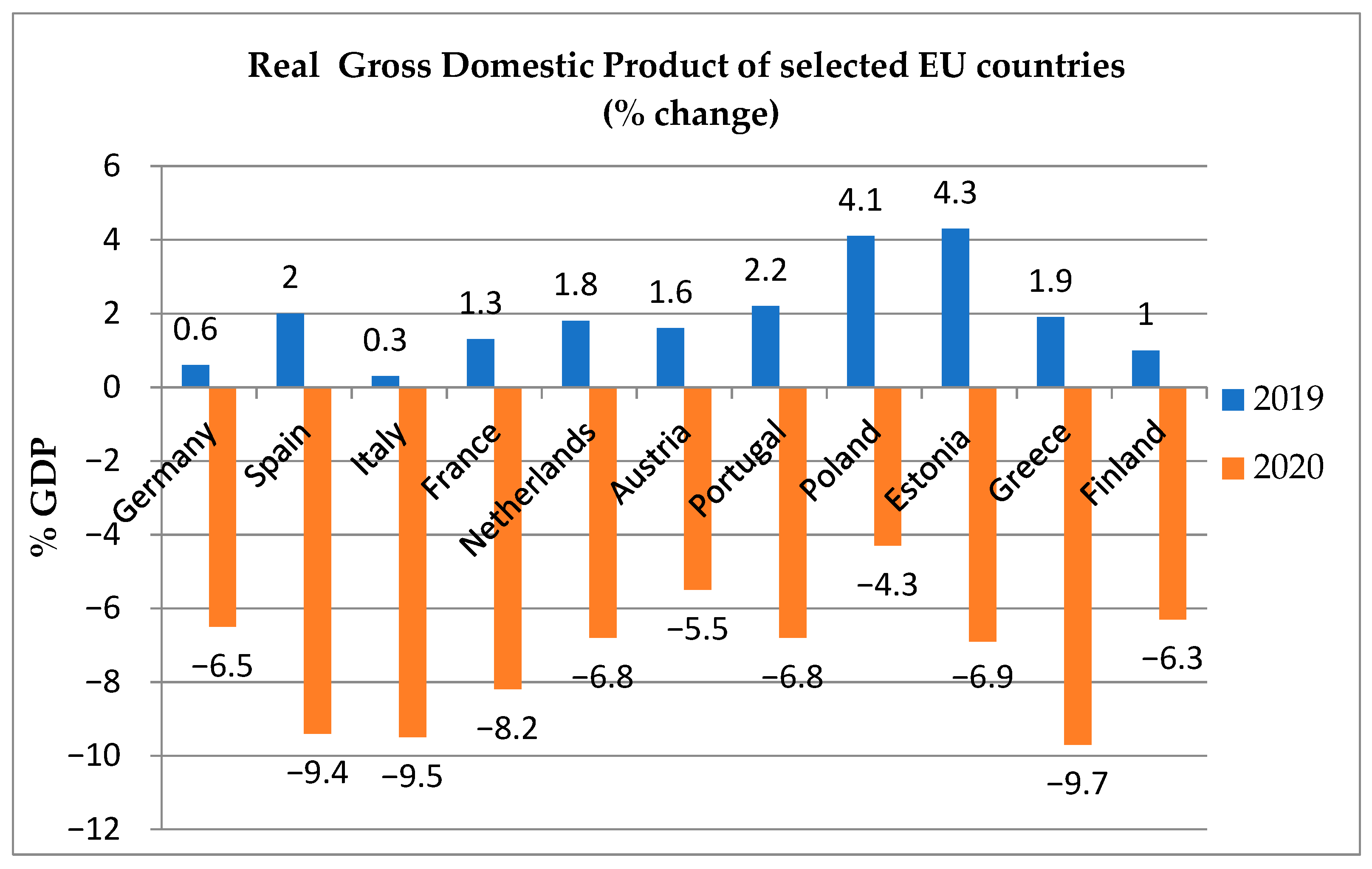

20]. However, the readings come from March, when the spread of the disease was just developing. The actual gross domestic product looks similar. In the entire European Union, GDP is forecast to fall to −7.7%. In the first half of 2020, the U.S. economy shrank by 5.0% year-on-year and the Chinese economy by 6.8% [

21]. The scale of the decline in several selected European countries in relation to the previous year 2019 is shown in the graph below (

Figure 5) [

22].

What will be the economic impact of the pandemic? This is not easy to predict, especially as there is a lack of historical references. Periods of high unemployment and low interest rates are the right time for new investments in low-carbon infrastructure this time, as the next step towards a transition to clean energy [

23]. This area of government interest should encompass concern for our future. We have been given one more chance, perhaps the last one to gain public awareness that sustainable development is the direction without an existing alternative today.