1. Introduction

Given recent academic studies highlighting the social aspect of sustainable development [

1,

2], it is apparent that all stakeholders should be considered in the sustainable development of society [

3]. As one of the three components of sustainable development, social development, especially in the disability field, has until now been somewhat neglected compared with the investigation on environmental protection and economic development [

4,

5,

6]. Noteworthy, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) established the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for the year 2030. Among these goals, one notably demonstrates to “promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels” [

7].

The facilitation of tourism for individuals with disabilities is a crucial dimension in sustainable tourism development, and it advocated the proposal of “Accessible Tourism for All [

8].” As Tourism for All [

9] reports, “Tourism is important to our lives, we believe that it is the right of disabled people to participate in all areas of community life. Few areas are more important than Tourism and Travel—which restore our energies, broaden our minds, and serve our deepest human instincts to explore new places and enjoy and share new experiences.” As determined by the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), the benefits of tourism participation by persons with disabilities could boost economic development along with the prosperity of the destination society. UNWTO emphasizes the availability of support services in destinations for people with special needs and the necessity to offer explicit guidelines on accessible tourism facilities [

10]. Accordingly, academic investigations for disabled tourists paid more attention to physical ability and age-related concerns [

11,

12], while the current literature about the difficulties encountered by travelers with visual impairments seems insufficient to address their desires.

People with visual impairments are often assumed to be not interested in traveling since travel is considered full of visual encounters [

13]. Indeed, they hold the same expectations of tourism as other social groups [

14]. In her travel adventure memoir, Susan Krieger, a professor with visual impairment at Stanford, described how fantastic the trips she experienced were [

13]. Visual impairment has been considered one of the most feared disabilities, often evoking emotional reactions that can cause extreme loss of independence and confidence in individuals facing this disability [

15]. Small, Darcy, and Packer [

16] (p. 946) stated that “for many sighted tourists, travel is an achievement, for those with vision impairments, this achievement can be profound.” As a starting point, the present study targets one specific disabled group in Hong Kong, namely those with visual impairments, to determine their standpoints towards tourism.

Hong Kong has approximately 174,000 people with visual impairments, representing 2.4% of the total population. After people with physical impairments, those with visual impairments comprise the second-largest category [

17]. Hong Kong is characterized by its economy and in people’s living standards [

18]. Increasing importance has been attached to enhancing the quality of life of the visually impaired community [

19]. The Hong Kong Government gives special consideration to visually impaired people and has endeavored to build an accessible living environment and promote their full integration into society, such as educating citizens the awareness of inclusiveness, removing the physical barriers, and developing various forms of digital products. Over the past few years, the recurrent expenditure on this matter has increased from HKD 16.6 billion in 2007 to HKD 31.5 billion in 2017 [

20].

Among the recurrent expenditure, the Hong Kong government set aside HKD 500 million on funding to address the needs of specific community groups and enhance daily living. In the funded projects, app development and innovative technology solutions were made to be the majority in assisting people with special needs to promote their full integration into society [

21]. The apps on smartphones could assist people with visual impairments to access information and blend into society [

22,

23]. Additionally, the current Hong Kong Budget will promote smart tourism that involves adopting smart technology to improve the tourism experience [

24]. Smart tourism defines as the tourism supported by integrated destination efforts to gather data derived from government sources and physical infrastructure by using sophisticated analytics through 5th generation mobile networks (5G) to transform that real-time and real-world data to enrich the on-site tourism destination experiences [

25]. The proliferation of smartphones has further expedited this development by merging communication, entertainment, social networking, and information search to assist tourists in their tourist experiences [

26]. The smart experience primarily targets for technology-mediated tourism experiences using smartphones during the trip and enhancing real-time monitoring, context awareness, and personalization [

27].

There are several advantages for smartphones as an assistive purpose to facilitate the on-site tourism experience for people with visual impairments, including enabling the affordability and accessibility for the target users, offering information access anytime and anywhere [

28]. Notably, since the Hong Kong Government aims to foster an inclusive society [

20], smartphones for visual impairments embedded into mainstream devices can help individuals feel less labeled or stigmatized [

29].

To date, little research has examined the aspiration of travelers with visual impairments, particularly in the realm of smart tourism. Through advanced smart technology, the features in the existing apps, such as navigation and object recognition, can meet their basic travel requirements. Yet, tourism experience involves a series of emotional encounters [

30]. Maslow claimed that humans would pursue the next level once the current level is fulfilled [

31]. While current apps successfully meet the basic requirements of visually impaired users (e.g., navigation and object recognition), the higher-order needs (such as their social needs, namely friendship, intimacy, and trust) have not yet been sufficiently fulfilled by such apps. The self-determination theory proposed perceived competence, relatedness, and autonomy as fundamental psychological needs [

32]. Based on the higher-level needs mentioned above, the research question is how to propose an approach to design tourism apps that can transcend the fundamental functions but offer higher needs, such as psychological needs related to emotions for people with visual impairments? The objective of this study is to propose a gamified application approach that can enhance the tourism experience for those people at an emotional level.

This paper is structured as follows. In the following section, we reviewed the extensive literature on the encountering issues of persons with visual impairments while traveling, the limitation of existing tourism apps for persons with visual impairments, tourism experience design, and the gamification approach.

Section 3 explains the methodology, focused on multisensory observation and interviews, to examine the needs and usage of mobile applications of people with visual impairments while on-site tourism.

Section 4 provides the results of these encounters. Here, content analysis is demonstrated in each section interpreting the themes. We concluded with a discussion concerning the on-site tourism needs and proposed a gamified approach with features to the tourism app design, which could enhance engagement, motivation, and enjoyment in the tourism experience.

3. Methodology

The study adopted the qualitative research approach that is often applied to study people with visual impairments, particularly in tourism [

69]. The goal was to establish a comprehensive understanding of the subjects and derive the corresponding requirements that would allow us to analyze tourism aspirations. Concerning the importance of the multisensory nature of the tourism experience for tourists with visual impairments [

16], we applied it as a methodological starting point to study the needs of such groups. The methodology mainly includes expert interviews and the methods derived from the sensory ethnography methodology to uncover the real-life stories and understand the potential needs of people with visual impairments (

Figure 1).

There are two rounds of expert interviews. One is gaining the necessary knowledge before researching with target participants. The second round is parallel as an expert validation of findings resulting from interviews. We conducted in-depth expert interviews and multisensory observation at the Ebenezer School, the only school for visually impaired people in Hong Kong, to understand how they are trained to live independently. We can learn their capabilities after fully understanding learning behaviors. Later on, based on their capabilities, we could propose the gamified approach that could empower people with visual impairments.

We spent three days observing how the students with visual impairments work and live at the Ebenezer School by conducting unobtrusive measures and “Fly-on-the-wall” observation. The unobtrusive approach is utilized to gain information without directly interacting with participants, through observations, nonreactive physical traces, and archives [

70]. Firstly, we conducted unobtrusive measures that involve walking, observing, taking photos, and taking notes around the entire school. The observation covered different floors, the playground, and vacant classrooms. The social worker accompanied and showed us the tools and other must-know techniques. During the observation, the social worker answered various questions from us. We conducted “Fly-on-the-wall” observation, which involved standing outside the classroom and observing through the window when students were having a class or taking an examination in the classroom. Note-taking and discretion are both keys for a successful “Fly-on-the-wall” method. When conducting this observation, we took hand notes to document what we observe and our reflection. We also marked down questions to follow up with interviewees later. In terms of discretion, hand notes could be less evident than documenting with a mobile phone or camera. “Fly-on-the-wall” observation was chosen because it enables researchers to acquire information unobtrusively by observing and listening without interfering with the individuals or behaviors observed [

70].

While conducting the observation at the Ebenezer School, some matters needed to be considered. As the sense of hearing of Ebenezer school students is very sensitive, researchers had to wear shoes that do not make too much noise. When conducting interviews or observation, we should never wear perfume, as the senses of the participants are delicate and sensitive. Additionally, while conducting the studies, the participants were always punctual, even arriving at least 10 minutes before. While asking them why they were so punctual, they mentioned that this was due to their disabilities, and they tried to leave home earlier to make sure they would not be late. Therefore, it is better to keep “being on time” in mind. Then, we conducted multisensory participant observations and interviews from sensory ethnography, reflecting of the ethnographic approach, with a focus on sensory perceptions and experiences [

71]. The innovative multisensory observation and interviews refer to walking, eating, and sensing with users.

To ensure that the conversation would run smoothly and naturally, dining and walking with the interviewees was beneficial because it could help the researcher raise the questions and help the participants to recall their memories naturally. We have engaged in sensorial observations through people with visual impairments participating in real environments. Furthermore, we have sought to understand their living environments and everyday activities. This process encompasses the material, digital, social, invisible, and intangible aspects. Multisensory participation, which spans from textures and sounds to unanticipated smells and unexpected sensory experiences, can enhance the researcher’s empathy towards the target users of this research [

71]. Questions relating to their feelings, opinions, and different ways of using their body and senses were asked to participants.

Additionally, we observed the participants undertaking activities together, such as walking, having dinner, and perceiving five-sense experiences in natural contexts, rather than in controlled settings, taking video in the research procedure that enables researchers to investigate the material and sensory qualities. During the video tour, we encouraged participants to express and show how they explore a new location using their multiple senses and utilizing various materials as props and prompts. Certain participants will actually feel, sense, and engage in a multisensory way with objects in the surroundings as a way of advocating their sensory qualities while engaging in the verbal decision-making procedure as well as explaining their meanings [

71]. The video will encourage the participants to utilize their whole bodies to demonstrate their multisensorial experiences via these behaviors. Overall, the multisensory interviews and observation can offer researchers a deep understanding and holistic explanation of everyday life and practice in ways that are impossible to reduce to number [

72]. The expert interviews can be regarded as a complementary method in the study. Talking to experts could provide a valuable perspective in a systems-level view of the project area [

73].

3.1. Selection of Participants

In the recruiting process, two types of blindness, congenitally blind and adventitious blind, were included. The different levels of visual impairments, comprising blindness, severe, moderate, and mild, were also considered in this study.

This study concentrated on people with visual impairments aged between 18 and 55 in Hong Kong. We chose this age range based on the following considerations: (1) they can afford the travel fee, (2) they are likely to travel, (3) they can travel independently, and (4) utilize mobile phones. The age range and considerations are also based on the suggestions and validations by other expert interviews conducted. Most experts confirmed that “visually impaired people over the age of 55 are relatively weak at traveling alone and their families do not feel comfortable allowing them to travel alone. It is more difficult for them to use smartphones as well while traveling.” However, seniors with visual impairments over 55 could be included in future studies. The ethical application was approved by the Departmental Research Committee, the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (reference HSEARS20161006001). Participants were provided with informed consent and all the related information about the purpose and context of the study.

As a downside to the sensory ethnographic approach, recruiting participants, especially visually impaired participants, was arguably the most challenging aspect of the project. The traditional interview is simply conducted in a controlled environment. It is a time-consuming process to identify the right interviewees willing to dine and walk with us. A snowball sampling tactic, a method which refers to the researcher accessing interviewees through other interviewees, applied in this study [

74]. Hong Kong Society for the Blind, the biggest blind community, supported by the Government and Hong Kong Blind Union, the first and biggest self-help organization managed by people with visual impairments, assisted us in arranging 10 visually impaired members, consisting of five males and five females, at their community to attend the in-depth interview. Their demographical information is illustrated in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. We also conducted expert interviews (

Table 1).

3.2. Data Analysis

Subsequently, a thematic analysis approach was implemented in the data analysis section. Thematic analysis offers a useful and flexible approach for analyzing the rich, complex, and intensive data from the interviews and observations to identify overlapping patterns of meaning [

75]. We uploaded all the transcripts, notes, photos and videos into ATLAS.ti (ATLAS.ti Scientific Development, Berlin, Germany), the qualitative data analysis computer software. As observational data such as notes, photographs and videos can be incorporated into the interview data as auxiliary or confirmatory research [

76], we analyzed all the different kinds of data together. We were open to seeking findings not demonstrated in the past investigation; hence, the method was to conduct coding by following the “bottom-up” inductive in which data are gathered, and theory is established as a result of data analysis adopted in this project [

77]. We followed the five steps of coding in the thematic analysis [

78]. Through the expert interviews, we gained valuable feedback from experts who offer a holistic view of this study and offer organizations’ perspectives, such as NGOs and social enterprises. Based on the findings from the need’s analysis, the experts provided a triangulation on the gamification approach to affirm and endorse the implication for gamified application design. After organizing and analyzing the observations, interview materials, and photographs, they were categorized into eight themes.

4. Results

Actual quotations from the participants generated the following themes of the research. The coding scheme consists of the following eight themes, with subthemes in each category (

Figure 6). The figure illustrates design inspiration, training, and love of traveling, which are the three most frequently mentioned themes clustered from the data. Under each theme, the indicated subthemes are also illustrated with percentages to show the importance within.

Figure 7 indicates the eight main themes corresponding to each interviewee. The detailed descriptions of the themes, with appropriate citations from the text to describe the meaning of the themes, are presented from

Section 4.1,

Section 4.2,

Section 4.3,

Section 4.4,

Section 4.5,

Section 4.6 and

Section 4.7. All quotes present in quotation marks in the body of the text or, if extensive, in indented blocks for ease of reading. Excerpts from interviews are included to provide an actual voice to the interviewees and have been selected as instances that represent the collective themes.

4.1. Understanding Their Attitude as Aspiration

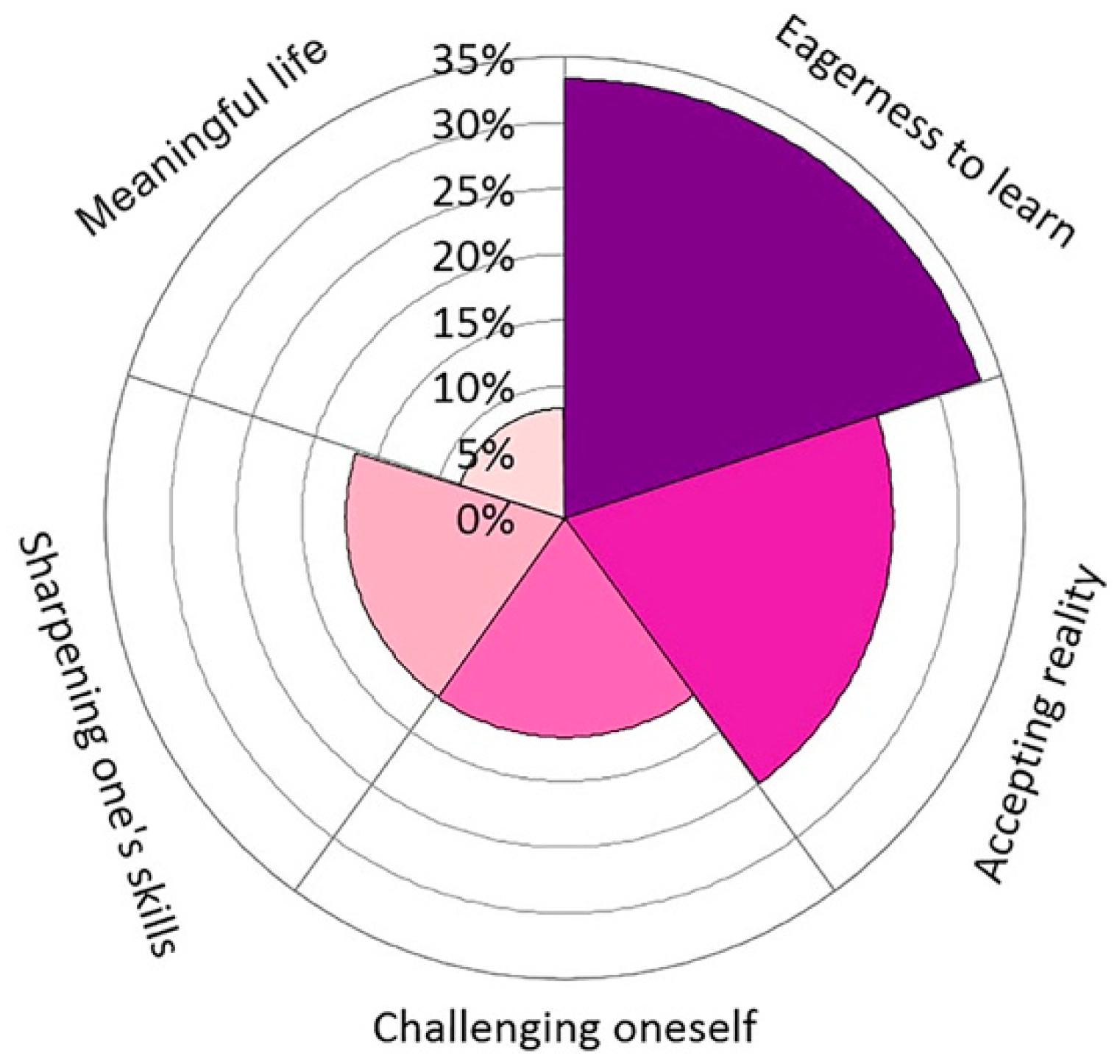

Under the theme ‘attitude as aspiration’, there are five sub-themes (

Figure 8). In this context, ‘meaningful’ means they can participate in activities that seem impossible because they are visual such as watching television, doing artworks, and traveling from their sighted peers’ point of view. The interviews highlighted the capacity and ability of people with visual impairments, and one participant emphasized: “What you can do, we can also do.”

During the observations, we noted that although people with visual impairments cannot see well, they put effort into learning through their laptops and books (

Figure 9).

When students with visual impairments study at school, they are encouraged to take care of themselves, such as take-off/put on clothes, organize their clothes, and do the housework. If they manage a challenge successfully, they can get two stamps, and if not, they can get one stamp. When they successfully challenge themselves, they can join the peer challenges; the winner can get two stamps. Four stamps can be exchanged for a secret reward. This is another way to use challenges, rewards, and collections to motivate students.

The majority of the interviewees emphasized that they wished to challenge themselves, although they understood how difficult it would be. One interviewee conveyed his wish, saying: “Yes, I wish to travel abroad alone. No matter how hard and what the result is, I wish to have this experience at least once.”

The interviews suggested that many people with visual impairments be eager to sharpen their skills instead of staying at home in their comfort zone. While willing to learn and cope, they may be concerned about other people’s attitudes. Human beings have an instinct to adapt to the environment, challenge various difficulties, and develop their abilities. Gamification on the app could fulfill the demand of people with visual impairments for autonomy that willing to finish particular jobs and the aspiration for self-development.

4.2. Understanding How They Had Been Trained

Under the theme ‘training,’ there are five sub-themes (

Figure 10). The premise of designing a meaningful gamified travel app for them is to understand their abilities. We could perceive their capabilities through observation and interviews of how they have been trained to adapt to life without vision. After fully understanding their possible abilities to travel independently, we can better propose the key features of applications that could empower them. The principal at Ebenezer School also stated that when they teach students at school: “Visually impaired students have lost their sight, but their other senses are trained to be greater.”

The first process of navigation training involves memorization. When students enter a new room, they have to memorize, for example, where the restroom is located by touching the objects in the room. As one participant pointed out, they could not memorize the location of the objects immediately, so they have to practice hard: “We people with visual impairments have to put more effort into memorizing things than normal people.” However, when they are outside their home, they also mentioned they cannot always memorize many steps between every two objects: “Many people think we remember the route by counting our steps. However, I cannot memorize all the steps.”

Another aspect of navigation training is combining one’s memories and senses. One participant expressed how he used his memory and his senses when he went out:

“I usually will touch and count the telegraph poles or the pillars. I remember there is a bakery where I can smell the bread aroma to recognize the location.”

O&M’s essential skill is clock positioning, where the relative direction of an item is described using the analogy of a 12-h clock. When showing the direction to people with visual impairments, people are recommended to refer to these clock positions (

Figure 11).

“This way” or “that way” is exceptionally unclear for some interviewees. The method of positioning employing clock position is a metaphor designed for the visually impaired to indicate directions. Another interviewee described how his teacher was training his O&M skills:

“I remember the positions of immobile things around me as reference points when I go out. They must be immobile things, not temporary things. My teacher told me there are some bus stations next to me when I go out of the building. Moreover, there are handrails and trees to my left. I have to count the handrails before arriving at the fourth tree; then, I must turn to my two o’clock position.”

Indeed, people with visual impairments are encouraged to try doing things by themselves. The principal at Ebenezer School stated the importance of being trained to be independent: “We teach our students that you should try to do everything by yourself before you seek other people’s help.” Cognitive training for visually impaired students includes the use of their other senses, which refers to smell, touch, hearing, memory, and imagination. Interviewees regarded sensory compensation as an essential coping strategy.

4.3. Needs for Sensory Compensation

Totally blind people who have lost their eyesight strive to use their other senses to experience and sense the world around them. Thanks to the multisensory participant observation and interview, we were able to obtain detailed ‘sensory compensation’ evidence from the interviewees. All participants highlighted the magnitude of sensory compensation, such as adopting auditory, olfactory, taste, and tactile experience.

In school, teachers will teach students cognition in sensory compensation. “Teachers teach us basic cognitive training, such as what we can eat and what we cannot eat by using our noses.” There is the sensory park for training students’ senses in the Ebenezer School (

Figure 12).

Sensory compensation by people with visual impairments is evident in the following quotations: “When my sight deteriorated, my mind tried to focus on other things such as what I heard rather than what I saw.”

Interviewees gave examples to demonstrate how they use their non-visual senses, such as hearing, taste, touch, and smell, to assist themselves in perceiving the world. One interviewee gave an example:

“As I approach a place slowly, I will always try to hear my footsteps. I can feel the change of the environment around me. If my skin becomes wet or cold, I know there is an entrance of a building since there is always an air conditioner near the entrance.”

Another participant touched on the same point:

“I use my senses a lot. I can recognize different sounds. On the way to the Blind Society, I hear the sound of construction work, and my shoes can feel the uneven wood boards. Above all, I know it is under construction now.”

[…]

“As I cannot see, I must try hard to find a way to get to know the outside world. I cannot always rely on the sense of touch, so I need to use the sense of hearing.”

The sense of hearing is quite significant: “When I use a white cane, I will tap the white cane and use my senses to see whether there is a barrier on the road. I use my sense of hearing to recognize the different sounds, too.” When they travel, they perceive unfamiliar environments through different senses: “When I travel, I try to build a sense of space in my mind. In the hotel, I will walk around and try to get to know which place has what.”

We were impressed by how perceptive people with visual impairments can be to feel the world by using their other senses. This can be shown in their travel diary. As stated by one informant: “In my travel diary, I describe the whole environment. I describe the whole atmosphere I experience.”

She then shared her experience about how she used her other senses to feel the atmosphere when she traveled around Tibet:

“…We arrived early. I could sense the golden sunlight from the sunrise. I can hear the sound of birds and the sound of the river. It is quiet there, with no cars. I can smell the aroma of the flowers and fresh air.”

After she wrote her travel experience diary in Tibet, she showed the diary to her friends with sighted peers who also traveled to Tibet. Her friends were surprised by how she focused on describing the sounds and aroma that they usually do not notice. Another interviewee shared his experience of using his senses when he travels to different places:

“Compared to Beijing, it is humid in Guangzhou. I can smell the dry and cold air while the air in Guangzhou is cold and wet. When I visited the suburban areas, such as the Baiyun Mountain, the refreshing air made me feel invigorated.”

The key findings in the sensory compensation section could be fed into app design, such as a feature to provide audio descriptions of different senses that enable people with visual impairments to better understand the destination.

4.4. Passion on Traveling

Under the theme ‘love traveling’ there are six sub-themes (

Figure 13). Despite potential difficulties that people with visual impairments face when venturing into the outside world, the study showed that, in contrast, they expressed a passion for travel.

Regarding traveling, sighted people may think it is pointless for people with visual impairments to travel because they cannot see at all. However, as expressed by one visually impaired respondent: “I can ‘see’ the scene by experiencing the atmosphere.” She shared her experience on ‘seeing’ students after school when she traveled to Nepal to exemplify this point:

“In Nepal, I was ‘watching’ students leaving school. Junior-grade students were first leaving school; they were jumping out from school happily. Then, there were intermediate grade students coming out from school, who tried to act mature and not show how happy they were. Finally, senior-grade students were coming out from school, who behaved like adults, just chatting with each other.”

They also love sharing their traveling experience with their peers: “I love to share where I went and what I ate in the ‘WeChat Moment’ because I want to share my travel experience with my friends.”

The majority of respondents maintained that they do not want to always stay in one place, so they like traveling. They can come into contact with the outside world by traveling. Most of the interviewees maintained that the most prominent benefit of travel is that it allows them to focus less on their disabilities temporarily and more on the experience of traveling itself, such as experiencing local customs.

The interviewees also wanted to try new things and experiences. Noteworthy, they can learn about different cultures in different places. Although they cannot see, they still wanted to use another method to experience the locals’ culture and customs, supported by another participant who stated the following:

“As the proverb says’ It is better to travel ten thousand miles than to read ten thousand books.’ I wished I could travel around.”

They also emphasized that they love trying the local food while traveling, and an interviewee stated: “I will use the food app to discover the local food.”

4.5. Needs for Understanding the Difficulties in Traveling

Under the theme ‘difficulties in traveling’, there are three sub-themes (

Figure 14). People with visual impairments encounter many difficulties while traveling. Most of the interviewees stated that they need sighted counterparts to go with them. This is because sighted counterparts can describe the scenes for them.

Although they travel with sighted peers, visually impaired people still face challenges while traveling. They complained about their awful travel experience with sighted people. Given the lack of audio description training, sighted people do not know how to describe the surroundings when accompanying people with visual impairments on outings. One participant expressed his dissatisfaction when his sighted peer accompanied him while traveling: “My friend only told me that there is much grass, how beautiful the sun is today, and there is much garbage on the beach.”

Even partially sighted people do not know how to describe the surroundings if they are not trained in audio description. One respondent with a low vision shared her experience when she accompanied three people who are totally blind on their outings.

“I have been diagnosed with low vision so that I can see a little bit. I once told them there are trees on both sides. However, they complained to me that ‘you only tell us there are trees, can you describe them in more detail?’ I then learned how to accompany the totally blind people gradually. When I accompanied them when we took a bus, I would tell them what shops appeared outside the windows. Alternatively, I would introduce where we were heading next.”

Therefore, the audio description with detailed descriptions in real-time should be provided. Visually impaired people depend on sighted people to describe their surroundings when traveling. However, visually impaired individuals currently have to accept the information passively, although they wish to obtain and control the information by themselves. This is in accordance with the self-determination theory [

32] that the following three elements are determined as intrinsic motivators: competence, autonomy, and relatedness. Understanding such obstacles enabled us to design a better experience for the target users.

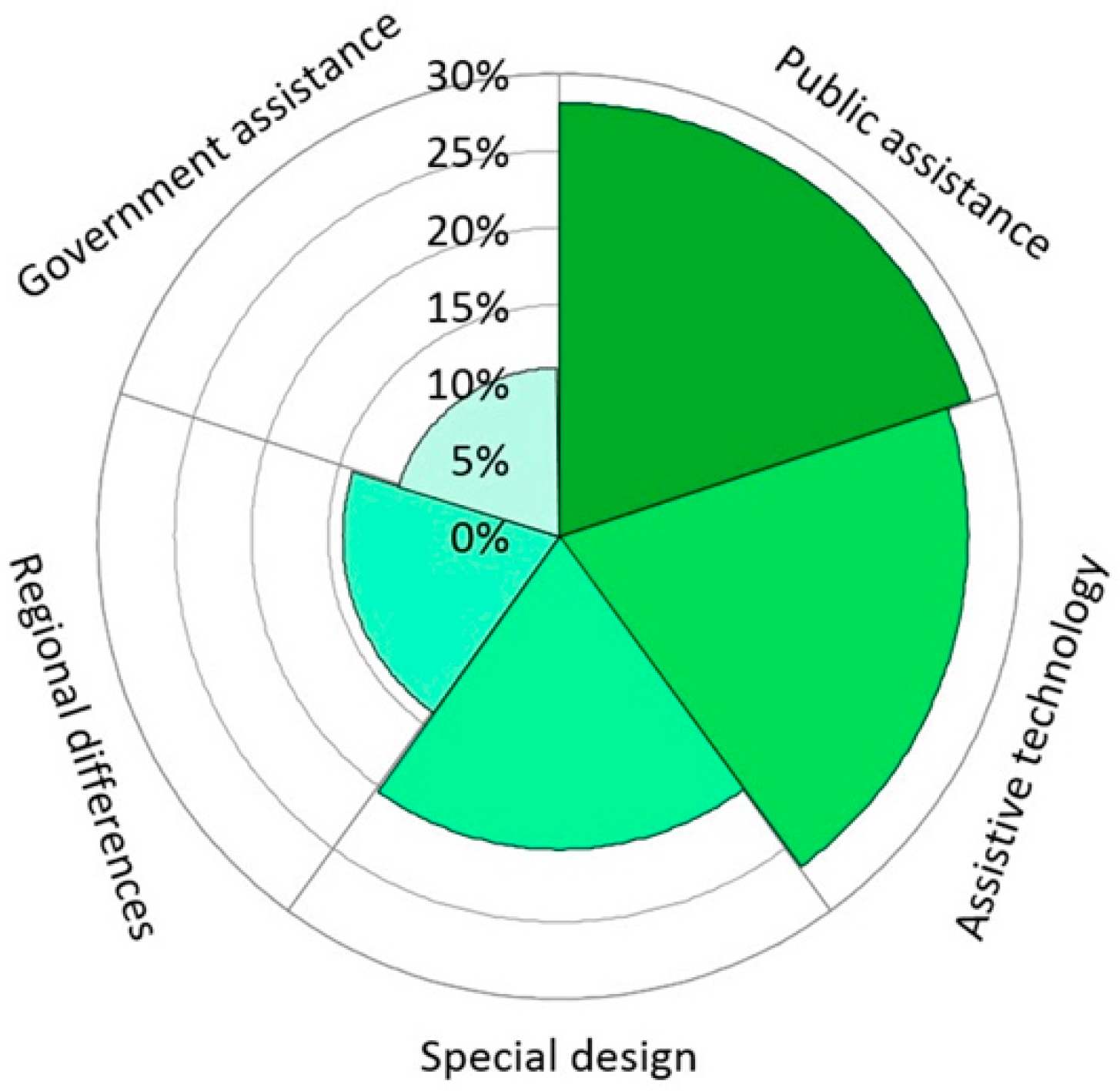

4.6. Needs for Accessibility

Under the theme ‘accessibility issues’, there are five sub-themes (

Figure 15).

Accessibility varies from area to area in different regions as commented by one interviewee:

“In Hong Kong, it is safe for visually impaired people to walk in the blind track by using a white cane. However, I do not think drivers will let you go first in Mainland China. The blind track is terrible in Mainland China. As such, I think the visually impaired in Hong Kong can walk independently.”

Another interviewee compared the accessible pedestrian signals (APS) in Hunan, Beijing, and Hong Kong:

“The APS in Hunan is not as loud as in Hong Kong and Beijing. Not all the traffic lights support APS, so only the main routes have it. All the traffic lights in Hong Kong have APS. The sound in Hong Kong is loud enough to stand out from the traffic sound. When I cross the road, I usually use my sense of hearing to listen to the volume of sound to make sure I am walking in a straight line.”

Another interviewee shared his travel experience of the regional accessibility differences. “The traffic lights in Japan are worse than the traffic lights in Hong Kong owing to the low sound. However, the lifts in Japan are better than the lifts in Hong Kong, because the lifts produce a sound to indicate to the visually impaired the floor information, whether the lift is going up or down, and whether the door is opened or closed.”

The Hong Kong government fully supports the community of people with visual impairments. When they move to a new area, they were provided with mentor services to be familiar with the community. The Hong Kong government also trains volunteers with audio description skills that enable people with visual impairments to visit museums and watch films. However, volunteers were limited that cannot provide services at all times.

The interviewees stated that the accessibility features on the iPhone help them to improve their lives significantly. iPhone’s ‘VoiceOver’ function can turn text into speech to enable visually impaired people to receive the information on their iPhone. To support different types of vision challenges, such as color blindness, the iOS system allows users to invert colors, to reduce white points, to enable greyscale, or to select from different color filters. IOS has a built-in screen magnifier called Zoom that allows users to view the magnified area in an independent window while allowing the other part of the screen to remain at its original size.

The interviewees were eager to show how the accessibility works on an iPhone by using the shortcuts they set on their iPhone. We observed that they could immediately turn the accessibility mode on and off. Users can significantly benefit from powerful accessibility features. However, enabling all the accessibility features, especially the VoiceOver function, would lead to much more power consumption. Therefore, another thoughtful design in the iPhone allows users to turn on the ‘Curtain’ function, which saves power by darkening the screen while retaining functionality. Apple has notably effective accessibility on the iPhone. However, the interviewees emphasized that all the accessibility features work fully only when developers ensure that the coding meets the requirements that enable the app to avail of all the accessibility features.

Most Hong Kong citizens have a positive attitude and are willing to help people with visual impairments. Many interviewees mentioned they would seek help from other citizens if they could not solve something by themselves while on outings. Besides the endeavor on building accessibility in public amenities, the Hong Kong Government also educate citizens to lead awareness of inclusiveness and accessibility (

Figure 16).

Figure 16 is one example that demonstrates how the Hong Kong Government tries to educate citizens on how to care about the guide dog when they were working with people with visual impairments on the bus. This education has remarkable achievements. While the researchers were conducting the walking together method from sensory ethnography in the street to accompany the people with visual impairments, we could hear some children said the dog was cute and beautiful. Their parents immediately told them that the guide dog was working, so we can only see but not touch them.

4.7. Needs for Design Inspiration

Under the theme ‘design inspiration,’ there are five sub-themes (

Figure 17). All of the interviewees agreed that ensuring the accessibility features on the iPhone is the most fundamental issue. All of them recommended that knowledge and information should be fully provided in the app design. In this vein, the detailed description and the audio description for the destination are vital.

They also suggested that traveling apps should provide various recommendations that users can follow. Another interesting point is that when asking participants for suggestions about the app design, all of them would emphasize some key points, such as the detailed descriptions needed while traveling. However, interviewees were able only to provide some suggestions based on the existing applications they had tried. Additionally, the features of the existing applications were limited. Therefore, the users did not know what the application could be in the future, and they did not fully articulate the exact need. We also tried to offer the features based on literature as prompts to interviewees. Yet, similar to existing applications, most of the features from the literature were based on the computer science and high-tech domain, such as the use of computer vision to enhance object recognition or navigation. The emotional and psychological needs, which seem to be intangible elements, were hard to present. Therefore, the in-depth interviews about their past travel experience (

Section 4.5) were useful, which can be added to the app design recommendation.

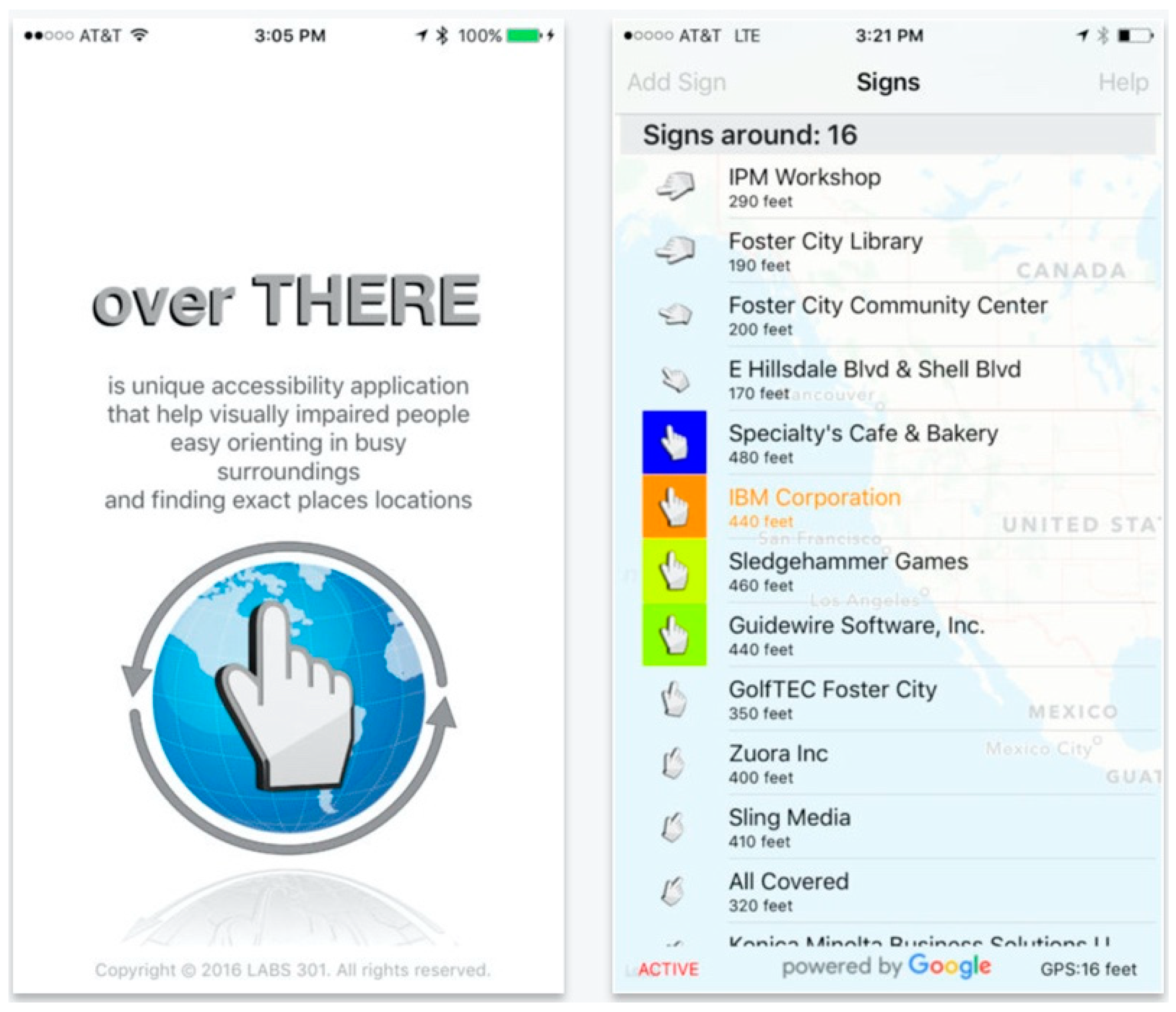

All interviewees emphasized that mobile apps assist them in different ways. Navigation and object recognition are the two essential app categories that most interviewees mentioned could benefit from in the existing applications. For the navigation function, they use Google Maps frequently. When they go out, they also need to take transportation. Therefore, they use a bus app to gather information. With the bus and navigation app, they can go out more easily compared to before. For example, the KMB app (KMB, Hong Kong, China), a bus information app, allows people with visual impairments to obtain bus information about when the bus will arrive in the station and also tell the users what the next station is, or how long it will be before they get off. When they travel, they prefer to use Uber (Uber Technologies, San Francisco, CA, USA) or DiDi (Didi Chuxing Technology, Beijing, China) apps, an efficient mobility service that can describe where they are, and the driver can pick them up easily and drive them to their destination quickly. Another category is object recognition. Some interviewees mentioned the challenges they face when traveling alone. They used an app called Tap Tap See (Cloudsight, Los Angeles, CA, USA), which utilizes the phone’s camera to recognize the station board and objects around them. Although the recognition accuracy of these apps is not 100% accurate, the interviewees maintained that the object recognition helped them considerably, and they were positive about this technology.

Additionally, they mentioned that they use WhatsApp, WeChat, and Facebook, which sighted people use for social purposes. These apps have relatively satisfactory accessibility. The lessons learned from the previous app design are two-fold. The first is the proper design we can learn from; the other is the poor design we should prevent. Indeed, most of the apps with negative reviews did not follow the guidelines from WCAG2.0 or the Hong Kong government’s guidelines. The best choice is using the checklist for accessibility checking. Several apps are full of small fonts in the interface, which can be applied in bigger size and bold, such as app OverThere (LABS 301, San Francisco, CA, USA) (

Figure 18).

Some interviewees complained that the accessibility function was not fully accessible in some apps because some buttons did not have detailed descriptions. Those buttons should be read clearly in the app, or it will cause repeated actions. The app should be divided into subtitles and sub-buttons so that users can choose from a clear hierarchy.

Even if all buttons were given descriptions, if there were too many buttons on one page, it will also make it hard for people with visual impairments to handle it. This is because they have to go through all the buttons from the left top to right bottom to find the one they need. The participants demonstrated a desire to play games on their iPhone, like the popular game Pokémon Go (Niantic, San Francisco, CA, USA). The playfulness component of exploratory play was emphasized by the interviewees. The participants maintained that there were numerous ways to learn about the destination but playing game-like applications and knowing about the destination is more fun. Compared with other conventional ways of learning about a destination (such as books, the internet, travel agents), playing a game related to a destination is more playful. However, few games or game-like applications are specifically designed for them. This finding draws our attention to the importance of considering gamification strategy for app design, which enables people with visual impairments to have a travel experience that is more engaging, motivating, and enjoyable. Interviewees also complained that some apps were useful initially but were not updated to solve technical issues and add more content. Therefore, continued app enhancement for people with visual impairments is crucial.

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings From Needs Analysis

The interviewees were generally particularly positive about travel and socializing with other people. Although they cannot see the scenes, they can engage with the atmosphere, customs, food, and the locals of the travel location. They also demonstrated a desire to play games on their iPhones. Therefore, we considered adding gamification elements to the app design to enhance engagement, motivation, and enjoyment in the travel experience.

The findings can be approached by Self-Determination Theory [

32] and Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs [

31]. The results show that the participants want to achieve self-actualization, such as challenging themselves and sharpening their skills once they have satisfied their physiological needs. They all agreed that as a tourist, in an unfamiliar environment, can contribute to their personal development, offer a chance to show one’s capabilities, and achieve a feeling of accomplishment. The study resonates with research, which states that the achievement of tourism for those with visual impairments can be profound compared to sighted tourists [

16]. The findings demonstrate that knowing one has overcome challenges in an unfamiliar environment can help one to cope with the day-to-day challenges in familiar places and prove that they can do it. The findings provide detailed information about how they are trained to use their other senses to engage with the world. Understanding their training enables researchers to comprehend their unique skills, which can be used for further design. The findings are corroborated by the existing literature from other countries that many visually impaired people can use their remaining vision, supplemented by their other senses and their kinaesthetic skills [

30]. Valuable results in the sensory compensation section can also be considered in app design functions, such as the usage of audio description, and how to utilize different senses to enable their travel experience.

During the interviews, all participants emphasized how smartphones have positively changed their lives. The accessibility features in iPhones are powerful and useful so that they should be fully used. In this way, when designers and developers create an app for visually impaired users should always consider the accessibility features in their minds and test the accessibility features of visually impaired users as early as possible. It is vital to follow the accessibility guidelines and regulations for app design. The participants are interested in challenging themselves to fully benefit from sensory compensation and to gain in-depth descriptions of their environments, which were among the key insights that led to the gamified app implication.

5.2. Gamification Approach

The PERMA model was selected as a framework for designing the app in this study because of its suitability for both tourism experiences and the gamification domain. From a practical gamification design point of view, the researchers also applied Lazzaro’s [

67] four kinds of fun theory and MDA framework [

68]. Mechanics are the instruments adopted to design games, whereas dynamics refers to how players interact with game playing. Aesthetics represent how the game enables the player to feel during the game experience. These aesthetics in MDA refer to eight types of the fun of playing games: narrative, sensation, challenge, fantasy, expression, fellowship, discovery, and submission [

79], as detailed in

Table 2.

In design practice, the three levels in the MDA model enabled us to start from the emotional points, then set the design goals, and conceptualize the dynamic user behavior in the gamified system. Zichermann and Cunningham [

59] assisted in designing the sequence and structure of app features. Additionally, the concept of the engagement loop discussed by renowned game designer and scholar would also be considered. The core engagement loop associated with game mechanics can be merged with positive reinforcement and feedback loops that ensure the user remains engaged in the game. The gamification design loop is based on the workflow: a motivating emotion that contributes the social call to action, which then contributes player re-engagement, and then feedback or reward.

Figure 19 represents this concept.

The player’s motivation subsequently drives the outcome in any system. Therefore, comprehending player motivation is of paramount importance when developing a successful gamified system. Based on Radoff’s [

66] general game experience research on game mechanics that entice positive emotions, Zichermann and Cunningham [

59] conclude with 12 motivations for gamification design. We regarded these motivations and related game mechanics as the dominant design theoretical approach of this project.

5.3. The Implication of Gamification of App Design

All the insights and findings provided several crucial design implications for designing a better tourism app for people with visual impairments. The participants admitted that, among numerous ways to learn about the destination, playing game-like applications and knowing about the destination are more enjoyable. Compared with other conventional approaches of learning about a destination (such as online, books, travel agents), playing a game related to a destination is more playful.

Pokémon Go is an app based on exploratory play; however, according to the interviewees, they stated it was challenging to manage the visual clues. The app could provide another opportunity for them to play Pokémon Go, with which users felt satisfied. Hence, adding the gamification strategy in the app design is applicable. Therefore, the challenges of gamification should be less considered. Indeed, for people with visual impairments, traveling is already a challenge to them. The app makes “challenge(s)” more meaningful and exciting, especially for assisting people with visual impairments. These two are the main ideas why games are so addictive to players. For those who like traveling but are hesitant, this app gives them the support and motivation to feel more comfortable. In this light, the notion of challenge, one of the standard gamification concepts, was shifted in the context of this specific audience.

Before adopting the gamification elements, full accessibility should be enabled. Apple has devoted notable efforts to improve the accessibility of the iPhone. Therefore, those who wish to create applications for people with visual impairments must follow the relevant international and local accessibility guides and fully understand all the accessibility features implemented on the iPhones.

The app could provide two travel modes (exploration mode and relaxation mode), that enable users to travel based on their preference. In the exploration mode, users will be given multiple tasks, including discovering hidden virtual items through a vibration pathway, finding hidden voices through narration, and seeking photo-sharing opportunities for locals. Here, the features of challenge, narrative, and discovery are drawn from LeBlanc’s eight types of fun [

79], and ‘missions’ from motivations for gamification design [

59]. In the chill mode, the app will recommend spots where users can relax or meditate. The feature provides ‘easy fun’ [

67].

Users could automatically receive feedback by listening to the music to check whether they have completed the mission. The reward can be points for a coupon or a part of a song. The user should check all the spots that the app suggests in order to gain the whole song or a coupon. Surprise, gifting, collecting, coupons, and reward system build on concepts presented by Lazzaro [

67], Zichermann, and Cunningham [

59], while joy and gratitude are associated with positive emotions [

56]. This feature stimulates the exploration of the destination space (‘easy fun’ in Lazzaro [

67]).

The app should provide “autonomy” that allows people with visual impairments to obtain and control the information themselves, and not just wait and accept passively for other sighted people to “feed” the information. Information feeding could be provided through an automatic well-designed audio description that consisted of the advice and stories from various senses when users pass by a new site within an attraction. The feature creates a sense of accomplishment by ‘unlocking’ them and triggers curiosity by providing new knowledge without user prompts [

59].

Users can leave messages for other visually impaired users, such as tips, experiences, and feelings. Other users’ messages can be liked, with the top 10 popular messages displayed on the leaderboard of the app. Users can also post questions that everyone can answer. Users can explore the wonderful experiences with valuable tips in each destination. Users can make friends with any users on the leaderboard by leaving a message for them. This feature provides users opportunities to make new friends and to expand their circle of friends. Getting attention, sharing, gaining status, competition, fame, leaderboard, and “a social call” to action in line with suggestions offered by Zichermann and Cunningham [

59], while Lazarro’s [

67] ideas on communication and social aspects of fun serve to build the foundation of positive emotions.

With a growing community, users could contribute to a detailed database of localized information. The information grows with the community, forming an utterly crowd-sourced tourism map of the world. Community, increasing content, community status, collaboration, co-creativity, and feeling of “growing” are particularly inspired by Zichermann and Cunningham [

59].

6. Conclusions

As a highly developed region, the Hong Kong Government has given special consideration to removing the physical barriers and educating the general public about disability, but the meaningful experience to ensure a higher quality of life for people with visual impairments should be offered. In order to comply with the sustainability goals from UNGA [

7] and the “Accessible Tourism for All” call from UNWTO [

10], this study first examined the needs of people with visual impairments and then investigated how gamification features can be implemented to enhance the on-site tourism experiences of people with visual impairments. The study conducted multisensory participant observations and interviews that provided a more comprehensive view of people with visual impairments in Hong Kong and an in-depth analysis of the aspirations of people with visual impairments.

From the research standpoint, this research has shown that the infrastructure in Hong Kong is highly accessible, and the awareness and knowledge of Hong Kong residents about accessibility to this infrastructure for people with visual impairments are relatively positive. This is because the Hong Kong government focuses on creating and promoting an inclusive and sustainable society so that all individuals can enjoy respect and equality in various aspects of life. In view of this inclusive society, there are more opportunities to create meaningful research beyond the basic needs of people with special needs. The finding is consistent with that other scholars stated that people with visual impairments had the same desire to enjoy traveling [

14].

All interviewees contended that they benefit significantly from smartphones (

Figure 20). The existing apps can meet their basic life requirements. However, few studies have examined whether apps can offer higher needs related to emotions for people with visual impairments. ‘Smart tourism’ with embedded and state-of-the-art technology, especially 5G, can transform real-time and real-world data to enrich the on-site tourism destination experiences.

The insights led to the specific design implications, which suggested that applying gamification could enrich the tourism experience and create an emotional connection with a place. Additionally, gamification could provide meaningful goals, a sense of purpose, achievement and enjoyment, and a feeling of autonomy, while traveling with the use of emerging technology.

This study proposed a gamified approach to future app design for people with visual impairments. As its foremost contribution to knowledge, this investigation advances the understanding of the needs of people with visual impairments, particularly from the mobile device from the tourism perspective. This new knowledge can contribute to filling both the research gap and product gap about people with visual impairments in the field of app design generally and in travel-supporting apps specifically. This project offered empirical notes on the implementation of sensory ethnography methods to understand visually impaired people’s needs. A further point is that the visually impaired community will derive a benefit by delivering them with more meaningful tourism experiences in the economic aspect of ensuring digital products are more affordable from this research. The research provides insights into social enterprises, organizations, and government entities, serving people with visual impairments. Ultimately, the findings of the study can contribute to academia in tourism and travel research, gamification research, user experience design research, and disability studies.

Although a diverse range of visually impaired participants were involved in this research, more participants could ideally have been involved. It should be noted that this study included most of the participants from a low-income background only, and they were all mainly linked to two organizations, one is the biggest and the other has the longest history, serving people with visual impairments locally in Hong Kong. Potential target users with a higher income who have more possibilities to travel outside their home city/country may require a more nuanced and customized approach regarding safety and cultural factors. Future studies should include further understanding and needs on the smart app design and prototype testing for people with visual impairments.