Sustaining Collaborative Effort in Work Teams: Exchange Ideology and Employee Social Loafing

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Hypotheses Development

2.1. Exchange Ideology and Social Loafing

2.2. Task Visibility and Social Loafing

2.3. Professional Respect and Social Loafing

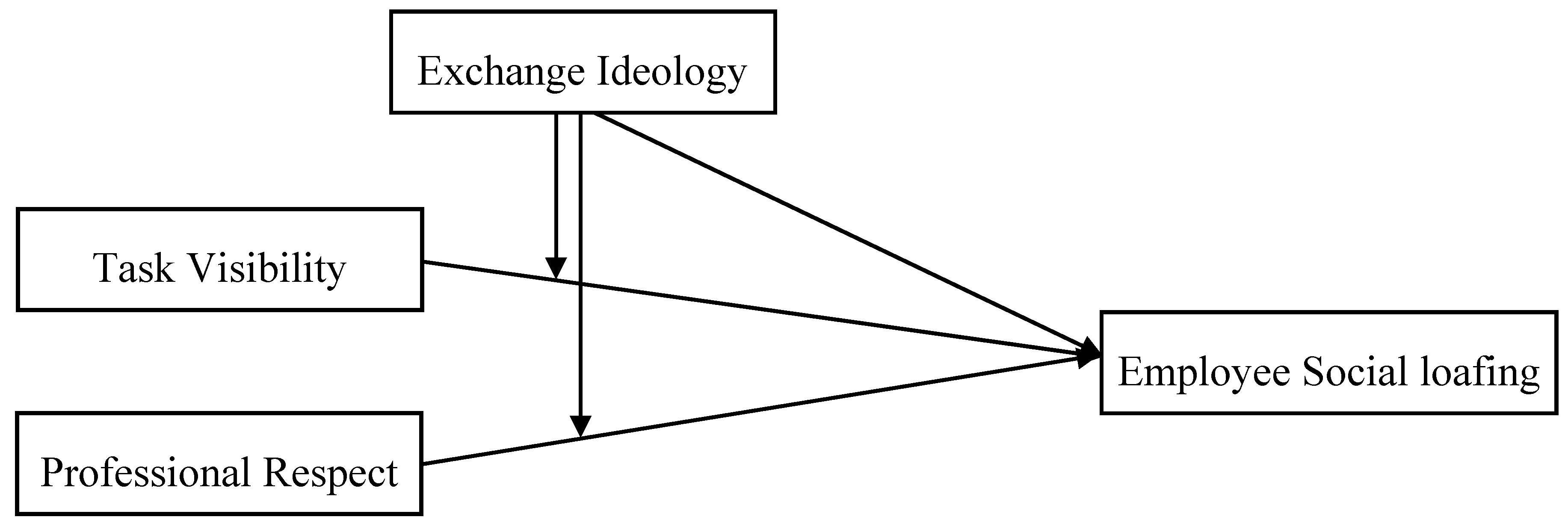

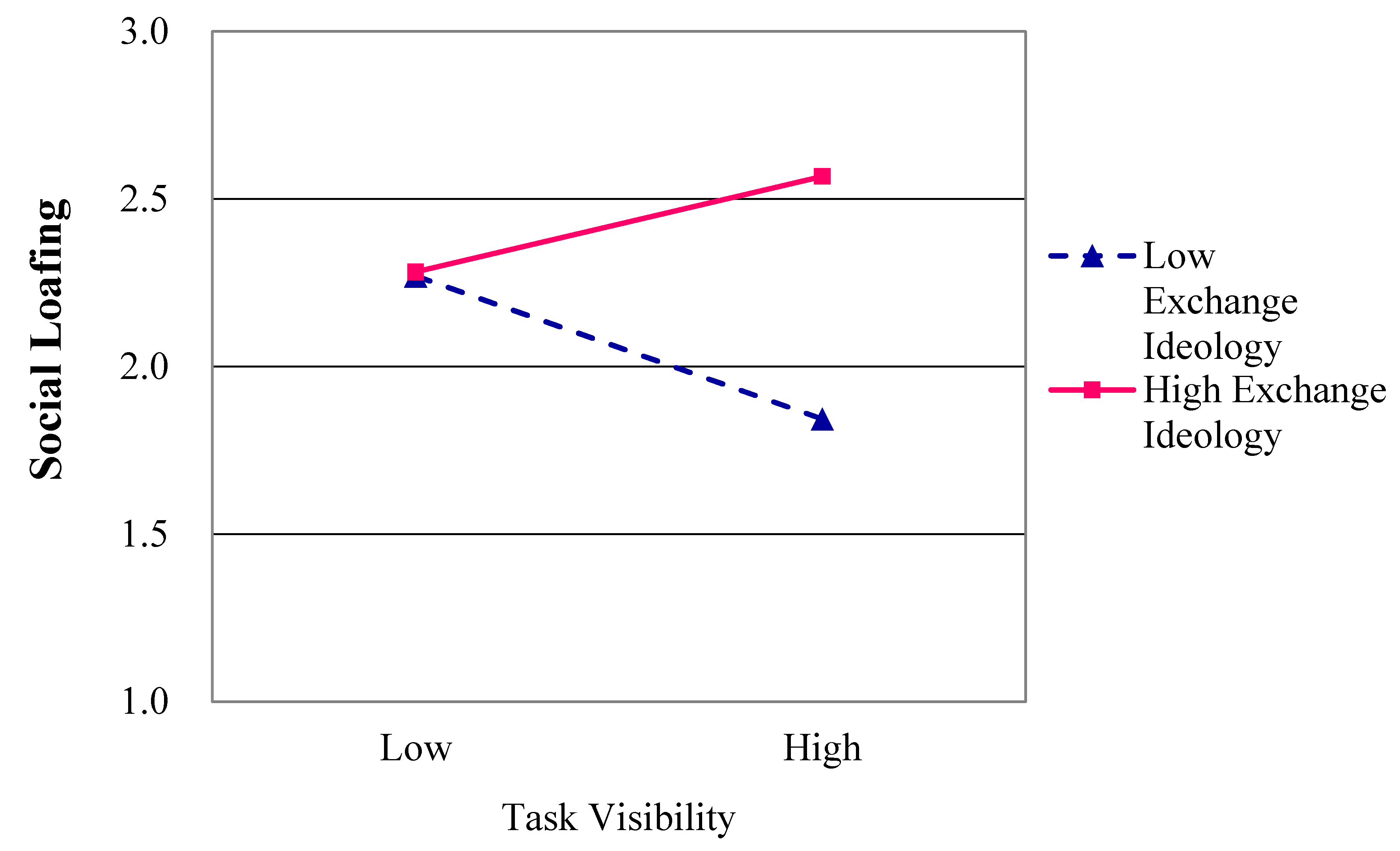

2.4. Interaction Effects

3. Method

Participants and Procedures

4. Measures

5. Results

Test of Hypotheses

6. Discussions

6.1. Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davis, J.H. Group Performance; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Price, K.H.; Harrison, D.A.; Gavin, J.H. Withholding inputs in team contexts: Member composition, interaction processes, evaluation structure, and social loafing. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1375–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karau, S.J.; Wilhau, A.J. Social loafing and motivation gains in groups: An integrative review. In Individual Motivation within Groups: Social Loafing and Motivation Gains in Work, Academic, and Sports Teams; Karau, S.J., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 3–51. [Google Scholar]

- Karau, S.J.; Williams, K.D. Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 681–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M. Asymmetrical effects of rewards and punishments: The case of social loafing. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1995, 68, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.N.; Kerr, N.A.; Markus, M.J.; Stasson, M.F. Individual differences in social loafing: Need for cognition as a motivator in collective performance. Group Dyn. Theory, Res. Pr. 2001, 5, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.W.; Karau, S.J.; Stasson, M.F.; Kerr, N.A. Achievement Motivation, Expected Coworker Performance, and Collective Task Motivation: Working Hard or Hardly Working? J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 984–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoon, H.; Tan, H.H. Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Social Loafing: The Role of Personality, Motives, and Contextual Factors. J. Psychol. 2008, 142, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smrt, D.L.; Karau, S.J. Protestant work ethic moderates social loafing. Group Dyn. Theory, Res. Pr. 2011, 15, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugihara, N. Gender and Social Loafing in Japan. J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 139, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, M. Social Loafing Tendencies and Team Performance: The Compensating Effect of Agreeableness and Conscientiousness. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2014, 13, 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, R.M. Social Exchange Theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1976, 2, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brief, A.P.; Aldag, R.J. The economic functions of work. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Rowland, K., Ferris, G.R., Eds.; JAI Press: Stamford, CT, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Origins of Perceived Social Loafing in Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.R. Task Visibility, Free Riding, and Shirking: Explaining the Effect of Structure and Technology on Employee Behavior. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.C.; Witt, L.; Kacmar, K.M. The interactive effects of organizational politics and exchange ideology on manager ratings of retention. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 62, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle-Shapiro, J.A.-M.; Neuman, J.H. The psychological contract and individual differences: The role of exchange and creditor ideologies. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Takeuchi, R.; Yun, S.; Wong, K.F.E. Social influence of a coworker: A test of the effect of employee and coworker exchange ideologies on employees’ exchange qualities. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2011, 115, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, T.; Snape, E. Exchange Ideology and Member-Union Relationships: An Evaluation of Moderation Effects. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseman, R.C.; Hatfield, J.D.; Miles, E.W. A New Perspective on Equity Theory: The Equity Sensitivity Construct. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vroom, V.H. Work and Motivation; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams, D.; Hogg, M.A. Social Identity Theory: Constructive and Critical Advances; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Goethals, G.R.; Darley, J.M. Social Comparison Theory: Self-Evaluation and Group Life. In Theories of Group Behavior; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin, Germany, 1987; pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Karau, S.J.; Williams, K.D. Understanding individual motivation in groups: The Collective Effort Model. In Groups at Work: Theory and Research; Turner, M.E., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 113–141. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K.; Harkins, S.G.; Latané, B. Identifiability as a deterrant to social loafing: Two cheering experiments. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 40, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkins, S.G.; Szymanski, K. Social loafing and self-evaluation with an objective standard. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 24, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Jaworski, R.A.; Bennett, N. Social Loafing: A Field Investigation. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwall, S.L. Two Kinds of Respect. Ethics 1977, 88, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Maslyn, J.M. Multidimensionality of leader-member exchange: An empirical assessment through scale development. J. Manag. 1998, 24, 43–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.M.; Wayne, S.J.; Liden, R.C.; Erdogan, B. Understanding Social Loafing: The Role of Justice Perceptions and Exchange Relationships. Hum. Relations 2003, 56, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harkins, S.G.; Petty, R.E. Effects of task difficulty and task uniqueness on social loafing. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 43, 1214–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaburu, D.S.; Baker, V.L. Extra-role behaviors challenging the status-quo. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 620–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology; Triandis, H.C., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; Volume 2, pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-P. To share or not to share: Modeling knowledge sharing using exchange ideology as a moderator. Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, L.; Reis, H.T.; Bond, M.H. Collectivism-individualism in everyday social life: The middle kingdom and the melting pot. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, P.C. East Meets West Meets Mideast: Further Explorations of Collectivistic and Individualistic Work Groups. Acad. Manag. J. 1993, 36, 319–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, N.; Manes, J. The compliment as a social strategy. Pap. Linguist. 1980, 13, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, K.; Lacinak, T.; Tompkins, C.; Ballard, J. Whale Done!: THE Power of Positive Relationships; Simon and Schuster: New York City, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswesvaran, C.; Schmidt, F.L.; Ones, D.S. Is There a General Factor in Ratings of Job Performance? A Meta-Analytic Framework for Disentangling Substantive and Error Influences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 108–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Employee age a | 34.13 | 5.51 | ||||||||||

| 2. | Employee gender a | 1.55 | 0.50 | 0.02 | |||||||||

| 3. | Employee organizational tenure a | 6.30 | 4.84 | 0.64 *** | 0.09 | ||||||||

| 4. | Employee tenure with their leader a | 2.03 | 2.21 | 0.26 *** | 0.06 | 0.35 *** | |||||||

| 5. | Leader age b | 41.95 | 6.17 | 0.25 *** | −0.08 | 0.33 *** | 0.02 | ||||||

| 6. | Leader gender b | 1.45 | 0.50 | 0.15 * | 0.58 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.11 | −0.24 *** | |||||

| 7. | Exchange ideology a | 3.70 | 1.15 | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.02 | (0.88) | |||

| 8. | Task visibility a | 4.96 | 0.96 | −0.03 | 0.19 ** | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.08 | 0.17 ** | −0.31 *** | (0.84) | ||

| 9. | Professional respect for employee b | 5.25 | 1.21 | 0.16 * | 0.10 | 0.15 * | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.14 * | −0.30 *** | 0.19 ** | (0.95) | |

| 10. | Employee social loafing b | 2.19 | 1.07 | −0.06 | −0.19 ** | −0.15 * | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.23 *** | 0.24 *** | −0.16 * | −0.45 *** | (0.92) |

| Employee Social Loafing a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2A | Model 2B | Model 2C | Model 3 | |

| Step 1: control variables b | |||||

| Employee age | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Employee gender | −0.08 | −0.08 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.05 |

| Employee organizational tenure | −0.10 | −0.14 | −0.09 | −0.06 | −0.07 |

| Employee tenure with their leader | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.04 |

| Leader age | −0.10 | −0.09 | −0.11 | −0.13 | −0.16 * |

| Leader gender | −0.18 * | −0.17 * | −0.17 * | −0.15 | −0.14 |

| Step 2: Main effects | |||||

| Exchange ideology (EXID) | 0.24 *** | 0.06 | |||

| Task visibility (TV) | −0.13 * | 0.02 | |||

| Professional respect (PR) | −0.43 *** | −0.42 *** | |||

| Step 3: interaction effects | |||||

| EXID c × TV d | 0.13 * | ||||

| EXID c × PR e | 0.15 * | ||||

| Overall F | 2.94 ** | 4.81 *** | 3.15 ** | 10.45 *** | 8.42 *** |

| R2 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.30 |

| Change in F | 14.39 *** | 3.74 * | 51.38 *** | 5.46 ** | |

| Change in R2 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.04 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Byun, G.; Lee, S.; Karau, S.J.; Dai, Y. Sustaining Collaborative Effort in Work Teams: Exchange Ideology and Employee Social Loafing. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6241. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156241

Byun G, Lee S, Karau SJ, Dai Y. Sustaining Collaborative Effort in Work Teams: Exchange Ideology and Employee Social Loafing. Sustainability. 2020; 12(15):6241. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156241

Chicago/Turabian StyleByun, Gukdo, Soojin Lee, Steven J. Karau, and Ye Dai. 2020. "Sustaining Collaborative Effort in Work Teams: Exchange Ideology and Employee Social Loafing" Sustainability 12, no. 15: 6241. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156241