In the following sections, key findings are provided that should be of interest to organisations responsible for developing landslide risk mitigation strategies and for assisting the GOB in determining the appropriateness of the government’s preparedness strategy. Sequentially, this paper explores: socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents; communities’ perception of the causes of increasing landslide hazards; migration and landslide susceptibility; the reasons for living in high-risk areas; the challenges of relocation to safe areas; and conclusions and implications.

4.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

The 208 respondents consisted of 60% males and 40% females. The respondents’ age ranges were categorised as 20–30, 31–40, 41–60, 61–70 and >70 years, and the percentage for each group were 35%, 34%, 13%, 8%, 6% and 4%, respectively. The average family size of the respondents was six members. The percentage breakdown of the completion of schooling up to junior level, secondary school certificate (SSC), higher secondary school certificate (HSC), graduate and postgraduate levels were 45%, 6%, 8%, 7% and 1%, respectively. The remaining 33% of the respondents were illiterate. Of the respondents, 14% were unemployed and the professions of the remaining 86% included housewives, businesspeople, students, day labours, transport workers, teachers, farmers and government employees, at 35%, 14%, 11%, 10%, 8%, 6%, 3% and 1% respectively. The house structure of the respondents were semi-built, bamboo-made, built, corrugated iron sheet and polythene sheet at 53%, 26%, 12%, 6% and 3% respectively. The ownerships of houses that included personally owned, rental, inherited from parents, government camp and lease were 67%, 21%, 5%, 4% and 3%, respectively. On average, the duration of occupying is 12 years. The duration of occupying a residence for 0–5, 6–10, 11–15, 16–20 and over 20 years account for 23%, 27%, 9%, 7% and 34% respectively. The respondents’ house locations included hill slope, valley area and hill-top and were occupied at 45%, 36% and 19%, respectively. The average monthly income of the respondents was USD 60. Of the respondents, 25% suggested there was no cash income. Of the remaining 75% of respondents, those with income range of below Taka (1 USD equaled to 85 Bangladeshi Taka (currency unit in Bangladesh) in June 2020) 5000, 5001–10,000, 10,001–20,000 and above 20,000 were 12%, 30%, 26% and 7%, respectively.

4.2. Communities’ Perception of the Causes of Increasing in Landslide Hazards

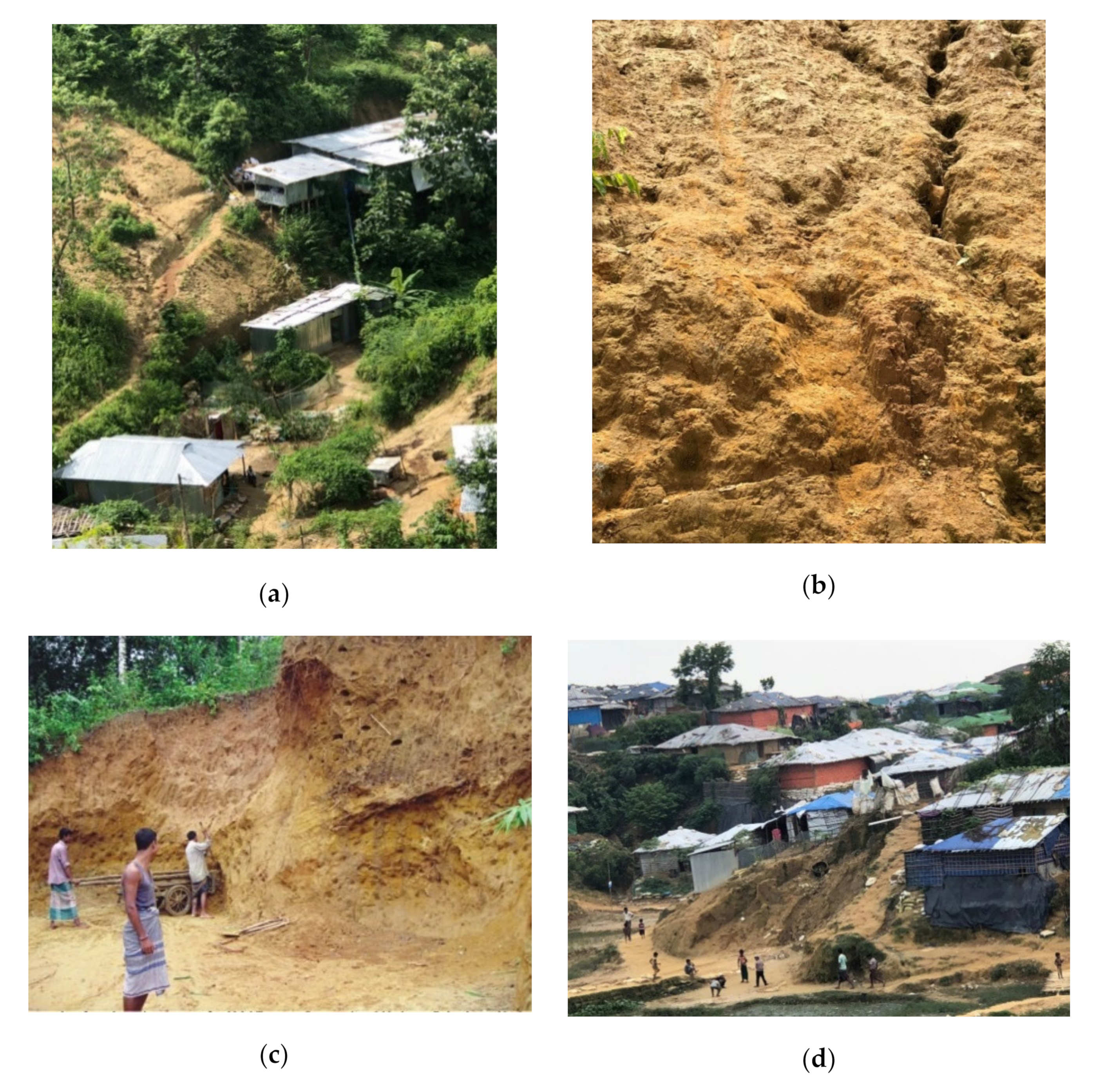

In response to the increase in recent landslide occurrence, 59% of residents attributed this to both natural and man-made causes. Separately, they opined that natural and man-made reasons constituted 39% and 2%, respectively. Of the natural causes, the residents believe that heavy rainfall is the most determining factor for landslide occurrence (

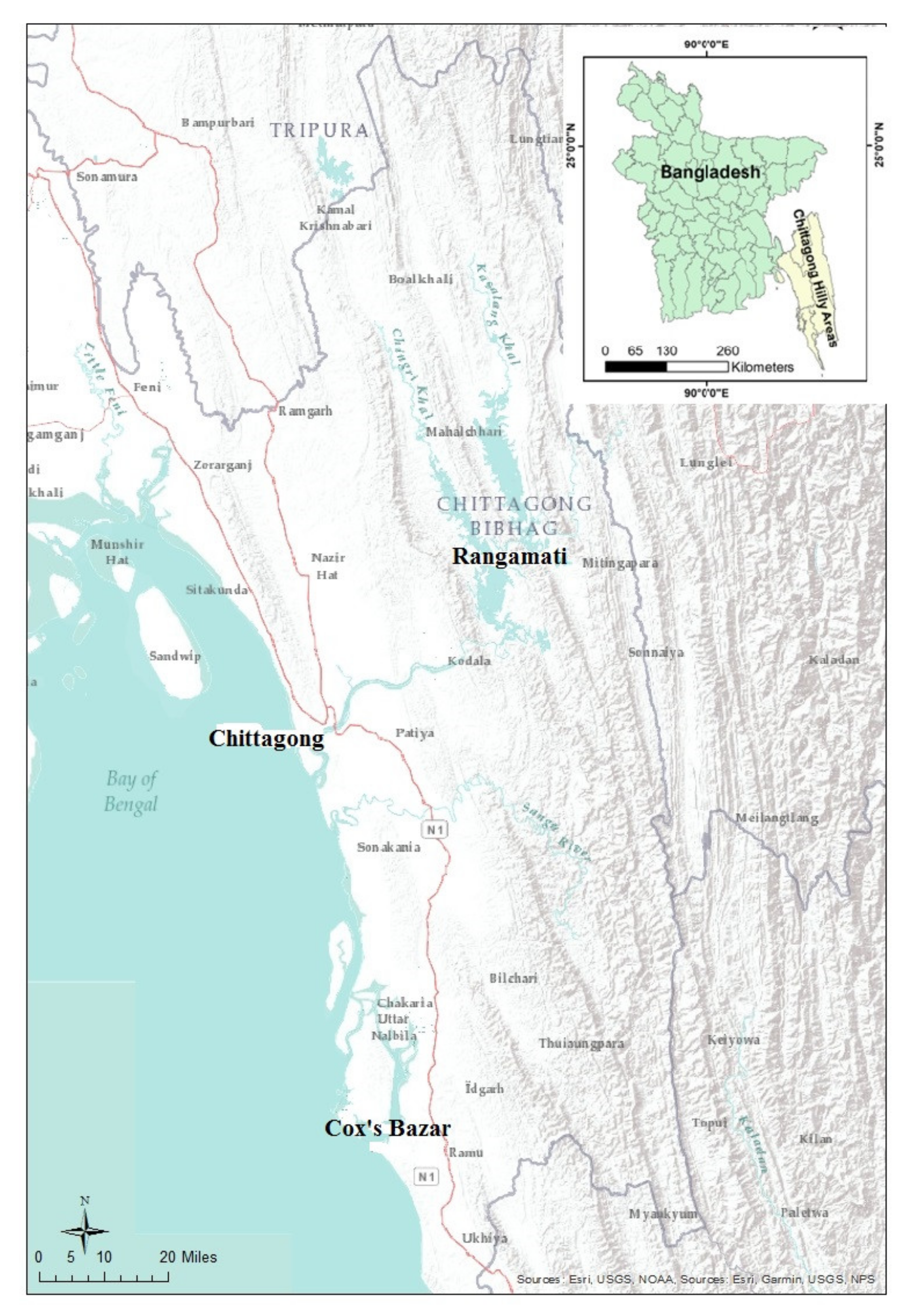

Table 2). This view coincides with expert opinion, which identified there was a record rainfall of 397 cm in Rangamati and 190 cm in Chittagong immediately before the 13 June 2017 landslide [

38]. Similarly, on 12 June 2007, a rainfall of 397 cm triggered landslides causing 150 deaths in Chittagong. Heavy rainfall invades inside through soil and infiltrates underneath the surface, creating pressure on the subsoil, and, subsequently, hilly soils become soft and loose and slides down to the surface [

23,

39]. Following the 2017 landslide, the residents who live close to landslide-prone areas become anxious if heavy rainfall starts in the area. From the experience of recent landslides, the residents believed that the occurrence of heavy rainfall for an extended period generates landslides (

Table 3). Generally, the residents in Rangamati do not want to attribute causes of landslide occurrence to man-made activities. However, when directed to some specific man-made reasons for landslide occurrence, they opined that recent increases in hill cutting, deforestation and human settlement in risk areas are contributory factors to the landslides (

Table 4). The local communities believed that, on the night of 12 June 2017, exceptionally severe thunderstorms occurred which shivered hilly areas. Heavy rainfall coupled with thunderstorms caused fragmentation and movement of soils in the hilly areas, which subsequently caused landslides.

4.5. Disaster Preparation and Response

Before the 2017 landslides, the residents in Rangamati have not experienced previous disaster. The landslides were an unprecedented disaster. The occurrence of a major disaster on communities increases disaster preparation [

41,

42]. Following the landslide disasters in 2007 and 2017, the GoB has significantly increased landslide preparation activities. Local communities have helped each other through warning dissemination, which should continue as ongoing activities for an effective warning respond. Currently, about 94% of the residents have received landslide warnings that are being disseminated by the local governmental organisations. When heavy rainfall lasts for a couple of hours, the Deputy Commissioner (DC) organises the warning about possible landslide occurrence to be disseminated through a hand microphone (

Table 7). If heavy rainfall lasts for several hours, the administrative staff under the DC sometimes visits the high-risk areas to execute the evacuation of vulnerable people. There are limited road transport systems for the people who live in the high-risk areas to move to a safe place. It is challenging to reach to communities and to undertake evacuation during heavy rainfall before any landslide occurs. Discussions with administrative officials suggest that there is limited logistical support to organise warning dissemination and evacuation in remote locations. It is challenging that many residents perceive there is a low-risk and consider a disaster might not occur. Even though the government officials organise forced evacuation for residents, the locals manage to return to the house in a short time.

Shamol (44), a resident who experienced damage to his building in 2017 at Rangapani of Rangamati, still considers the area safe for him.

Of the respondents, 77% believe that there are safe public infrastructures where they can take shelter if required. However, during the previous disaster when they faced evacuation, 37.5% moved to relatives and neighbours’ houses. The communities’ usage of public buildings such as municipal halls, public school buildings and cyclone shelters as shelter places were 28.9%, 10.6% and 1% respectively. It was noted that 22% of the people remained at their houses despite being made aware of the dangers of landslide occurrence. By experiencing issues in shelter centres during past disasters, 68.3% of respondents suggest they would not move to a shelter centre even if there were substantial landslide occurrence in the future. Some residents stated they were kept in the shelter centre as fish shelved one after another. There are differences in views among residents coming from various places. The native Bengali residents usually do not want to go to the shelter centre because of maintaining their prestige/self-esteem; they further opined that people who migrated from other districts went to shelter centre. Comparatively, wealthy people having their buildings had experienced shame going to a shelter centre. The tribal community suggests they would not go to a shelter centre because they were not anxious about landslides. Findings from FGDs suggest parents with young daughters do not want to move to a shelter centre where they might not have a private room and could experience sexual harassment. They also opined that, even if they went, they could experience theft at their houses.

Of the 208 participating respondents, about 12.5% of respondents received training on landslide risk reduction. However, the remaining 87.5% did not receive any training on landslide risk reduction. Those who attended the training learned about warning signals, identification of hazards and first aid procedures. The participants received training on landslide risk reduction from the district and sub-district administration. The city corporation, central government, NGOs and volunteer organisations provided training to the vulnerable communities. Of those who participated in the trainings, 62% opined the trainings were beneficial but the remaining 38% concluded that the training outcome was not practical due to the lack of reality.

4.6. Challenges of Relocation to Safe Areas

The people who live in the high-risk areas do not want to relocate to new safe areas. Many residents opined that a landslide is not a scatter event; they are living in this area due to livelihood opportunities. The majority of the respondents do not consider the area is at risk of a landslide. The tribal community suggests that they would not relocate to plain land. However, they suggest they might consider relocation if this can be organised for the entire tribal community. If the GoB plans to relocate a cluster of tiny houses without livelihood opportunity, they would not accept the relocation package. Every respondent preferred a single house with livelihood opportunity. When severe adversity was faced during the 2017 landslides, some 2124 people moved into 19 shelter centres in Rangamati [

43].

Findings from FGD in Cox’s Bazar: “some residents opined that they grew their generation there. It is their heredity, culture, sense of place and living within and adjacent to the places. They have not undergone that hardship to leave the area to seek only for a safe place. They have spent their whole life saving to buy land and construct the houses; now someone (indicating to Governmental officials) says to leave the houses. This poised a question; why do we listen to them? If we own our land, why do we move to another area? This is not a feasible way to solve the problem. No area in Bangladesh is completely safe.”

People who do not have permanent income opportunities and are landless would move to a suitable place. FGD with residents in Rangamati: “We do not want to relocate to a tribal majority area because we are not safe among them. On extreme occasions, those people who have recently migrated to Rangamati and reside in rental houses could agree to relocate to other areas. If we need to die, we die at this place. We would not move to the new area.”

Of the 208 respondents, 54% completely disagreed with relocating to new areas. About 40% of respondents want to be relocated to a suitable place. The remaining 6% indicated a few specific suitable places that include inside Chittagong and Rangamati cities and better places adjacent to their current houses (

Table 8). Some poor and landless residents would relocate if construction materials, cash, employment and space for constructing a house in plain land were provided. Concerning reasons for non-relocation, the answers included a lack of suitable facilities in a new location; not having a safe place in adjacent areas; possible fragmentations in family relations; do not consider current living areas as at-risk places; and affection for the current location. It is a prerequisite that economic, social and psychological aspects of the community would need to be carefully evaluated to identify an appropriate place for relocation.