Abstract

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), also known as Global Goals, were adopted by the United Nations (UN) in 2015 with a universal call for action to achieve a better and global sustainable future by 2030. Public-private partnerships (PPPs) have been recognized as an innovative mechanism for achieving UN SDGs because they help the public sector provide basic goods and services by enabling the use of the experience and funds of the private sector. This study examines the PPP network by visualizing the relationship among stakeholders through social network analysis. Considering the case of the Partnership for Green Growth and Global Goals 2030 (P4G), this study investigates the actors and the relationship between the actors by stage and year. As a result, the study visualized the network of PPPs in P4G, thereby revealing that the partnerships were evolving since the participants’ relationships became stronger each year. Moreover, the role of each actor became clearer at each stage. The findings provide practical guidance for practitioners interested in promoting international development cooperation through PPPs in the future.

1. Introduction

As globalization progresses, partnerships are more important than ever, especially when various social problems extend beyond country borders and require action from both public and private stakeholders. Therefore, cross-sector partnerships have been established between various participants, such as government, international organizations, civil society, the private sector, and key stakeholders at the local, national, and intergovernmental levels, to promote innovative solutions and address the global challenges of sustainable development [1].

As the United Nations (UN) has adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, as well as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, partnerships have become even more important. Goal 17 aims to “strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development,” focusing on establishing support networks between developed and developing countries, as well as building and improving partnerships between countries and international organizations [2]. In other words, it emphasizes that partnerships are the basis for achieving other goals.

In this regard, public-private partnerships (PPPs) have been recognized as an innovative mechanism for achieving UN SDGs because they help the public sector provide basic goods and services by enabling the use of the private sector’s experience and funds [3]. Although PPP has been variously defined by researchers and practitioners [4,5], the UN Foundation has suggested several PPP requirements in the context of international development [6]. According to these requirements, PPP describes the situation where each participant shares risks to solve a common agenda, combining possible rewards with their resources, skills, and expertise. Therefore, the strength and importance of PPP lie in the fact that cooperative partnerships are more effective in solving complex social problems than single actors.

Thus far, even though numerous studies have defined PPP [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14], no study examines PPP from the cooperation perspective. KS et al. [3] attempted to analyze the PPP structure by applying network theory. However, the findings cannot be generalized since only one project is examined.

Therefore, this study examines the PPP network by visualizing the relationship among stakeholders through social network analysis (SNA). In particular, the analysis at each development stage (start-up to scale-up) and year provides meaningful suggestions for practitioners interested in developing international development projects through PPP. This scope for suggestions is because it is possible to identify which actors should comprise which stage and the role of each actor. Hence, this study selected and analyzed partnerships of “Partnering for Green Growth and the Global Goals 2030” (P4G), a worldwide PPP platform, established in 2018, that aims to elevate public and private participation in international development in line with achieving the SDGs and the Paris climate agreement. P4G is an innovative PPP platform that brings together business, government, and civil society organizations to develop solutions to meet humanity’s greatest needs in five main areas: Food and agriculture, water, energy, urban, and circular economy. Moreover, it currently invests in over 50 PPP projects in developing countries. Therefore, considering partnerships of P4G provides the opportunity to examine how PPP evolves by stage and year, which could inform the future implementation of PPP in international development cooperation.

2. Literature Review

Sustainable development is a global problem. Nonetheless, addressing the problem is challenging since sustainable development must be assessed from a multi-dimensional perspective. Van Huijstee et al. [15] reviewed the literature on partnerships for sustainable development and found that the literature has mostly focused on institutional and actor perspectives. These perspectives consider partnerships as governance regimes and a practical instrument for SDG achievement, respectively. Thus, not only effective partnerships within nations but also global partnerships across nations are required to achieve the SDGs. Furthermore, under the UN’s 2030 agenda, the five critical areas emphasized include partnerships that are essential to accomplishing SDGs [16]. Beisheim and Liese [17] suggested that transnational partnerships are necessary for the effective promotion of sustainable development. Multi-stakeholder partnerships (MSPs) have been recognized as a “new form of global governance with the potential to bridge multilateral norms and local action by drawing on a diverse number of actors in civil society, government, and business,” as announced at the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg 2002 [18]. However, Pinkse and Kolk [19] noted the challenges regarding MSPs in addressing climate change issues. Thus, the effective operation of the partnership requires corporate involvement. Moreover, the main role of the corporate actor is to provide resources to bridge the learning gap (i.e., financial resources, skill, or expertise).

In this context, PPP has emerged as a new way to achieve sustainable development. PPPs first emerged in the 1950s; they were formed to address social problems between the public and private sectors. The two types of PPP (credit assistance and grant-type aid) represent partnerships for the construction of social overhead capital and infrastructure and launching international development projects such as official development assistance (ODA) projects. Given that global interests have shifted to sustainable development, PPP has become crucial for international cooperation. PPP has often been compared with MSPs; MSPs are voluntary agreements between different stakeholders, while PPPs are contracts between a government and a company [20]. The advantage of PPP stems from project duration and financing. The government (public) provides governance at the institutional level such that partnerships can benefit from the binding force of the integration. Meanwhile, private stakeholders procure funds for projects and skills that match the competencies of the partnership and fit within its scope. Colverson and Perera [21] demonstrated that PPPs have the advantage of multi-strategies on financing for accomplishing projects.

According to Lee [22], since many problems related to sustainable development have been enlarged beyond the competency of a single sector, both the government and private sectors must assume social responsibilities. The World Bank [23] proposed PPPs as effective for achieving SDGs. Moreover, a well-designed and implemented PPP under relevant regulations accelerates the project or business efficiency and sustainability in the provision of public services.

Various studies on PPPs have been conducted. Marx [24] contributed an article covering the PPP for sustainable development by analyzing the design and its impact on the PPP. The prior design of the PPP structure is the critical point of success in the business, as the PPP plays a role in climate cooperation. Kumaraswamy and Anvuur [25] showed the importance of PPP from the perspective of sustainability by developing the selection methods for the operation team based on PPP. Zou et al. [26] also identified the critical success factors for relationship management in the PPP project. Thus, for projects based on PPPs, relationship management is the first step to project success. Evidence on the importance of PPP can be found in the national policy literature. Chen et al. [27] investigated PPP-related policies in China and found patterns related to PPP and sustainable development. They found evidence of development in PPP-related policies toward sustainable development as a result of a three-phase analysis of the 1980–2017 period. Cheng et al. [28] agree that sustainability considerations have oriented PPP in China. Zhou and Smith [29] conducted a case study to identify the best practice in PPP from a sustainability perspective. Importantly, Hueskes et al. [30] suggested that relevant governance should oversee PPPs in improving sustainability, which is an essential issue in the partnership.

Clearly, the literature has demonstrated the importance of PPP for sustainable development. Moreover, it is more relevant than ever to utilize the PPP-oriented international network as a global cooperation instrument for sustainable development, such as climate mitigation. Furthermore, the existing literature on SNA attempted to investigate the global business and economy system [31,32], as well as the corresponding action on climate mitigation [33]. However, while the importance of PPP for sustainable development has been emphasized, the cooperation system for climate mitigation has not been investigated.

Divjak et al. [34] emphasized that the SNA method had never been adopted to analyze a project network. Hossain [35] analyzed an organization network from the employee perspective to reveal the centrality of the organization in conducting millions of funding projects. He concluded that well-connected people in the network can handle more projects than others; moreover, they have the opportunity to initiate a funding project.

We apply the same hypothesis [35], where, from the PPP perspective, the importance of well-connected stakeholders will be magnified for global climate cooperation. However, Streeter and Gillespie [36] noted a disadvantage of SNA since it depicts a network in a static sate and is limited to single variable accounts. To overcome this limitation, we apply SNA across multiple periods to capture the change of state of the network among stakeholders. In short, this study investigates P4G, a climate cooperation PPP-based platform, to examine its limitations and opportunities by analyzing the development pattern of the climate cooperation platform.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Study: Partnerring for Green Growth and Global Goals 2030 (P4G)

As aforementioned, P4G is a new initiative designed to facilitate PPPs in delivering on the SDGs and the Paris climate agreement. Different types of stakeholders, such as governments, companies, non-profit and non-governmental organizations, international organizations, and research organizations, have participated in various partnership programs to help meet humanity’s needs in five key areas: Food and agriculture, water, energy, cities, and circular economy.

The P4G partnership program database (the database is obtained from the P4G website (www.p4gpartnership.org)) contains information on 56 partnerships from 2018 to 2020. The data include partnership name, year, focus area (SDG target), partner (donor), recipient country, and a short description of the partnership. The data also includes partnership stages, indicating how much the partnership has matured. The stages are divided into three. The first is “start-up,” while the matured stage is “scale-up.”

Table 1 shows the number of partnerships by stage and by year. Among 46 partnerships, 37 are in the start-up stage, while 10 are in the scale-up stage. The year 2019 has the largest number of partnerships, followed by 2018. The year 2020 has the smallest number of partnerships since the P4G scale-up projects have not yet been selected.

Table 1.

Total number of Partnering for Green Growth and Global Goals 2030 (P4G) partnership programs.

3.2. Analysis

SNA is a useful method to analyze and visualize how relationships between stakeholders constitute a complex network structure. It enables the identification of networked structures in terms of nodes (stakeholders within the network) and the links (relationships between the stakeholders) connecting them [37]. One of the key features of SNA is that network structures can be visualized as network maps. In a network map, nodes are represented as points, and links are represented as lines. This network map helps to identify which stakeholders (nodes) have more (or less) cooperative relationships (links) than others in the network.

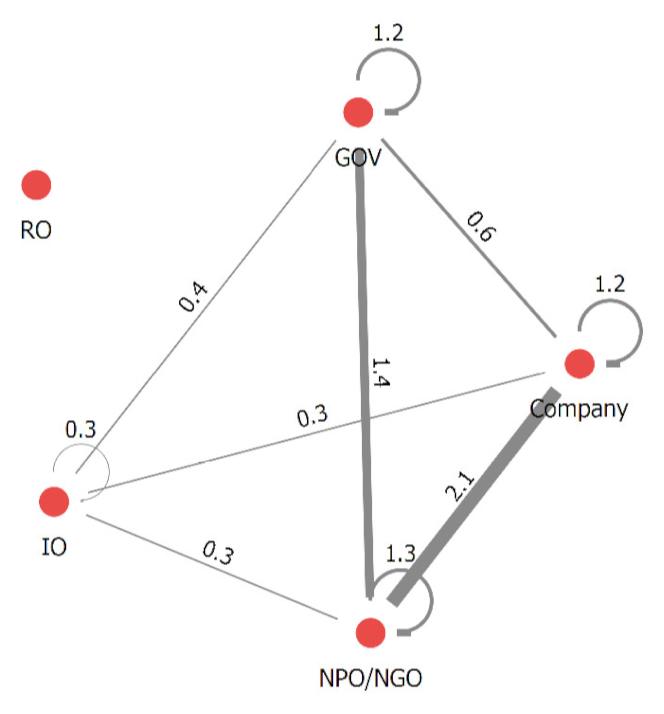

In this study, SNA was used to investigate the cooperative relationships among donors participating in P4G partnership programs and identify how these relationships evolve by partnership stage (start-up and scale-up). The analysis was conducted in the following steps. First, the donors participating in P4G partnership programs from 2018 to 2020 were set as nodes. It is important to note that the donors in P4G programs were divided into five categories (government [GOV], company, non-profit and non-governmental organization [NPO/NGO], international organization [IO], and research organization [RO]) to analyze organizational level interactions. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics denoting the number of donors by type, partnership stage, and year.

Table 2.

Number of donors by type, partnership stage, and year.

Secondly, cooperative relationships between these donors were set as links. It is important to note that the number of cooperative relationships between each donor was considered as the weight of the link. Thus, to calculate the normalized weight, the original weight was divided by the number of cooperative relationships per program.

Finally, network maps that demonstrate cooperative relationships among the donors were drawn annually from 2018 to 2020 according to partnership stages to track the network structure changes over time. In the network maps, the donors (nodes) were represented as points, and the cooperative relationships between the donors (links) were represented as lines. Further, the weights were represented as the thickness of the line. The maps were first drawn in a stress majorization layout, which is among the most widely used layouts. However, each node is subsequently moved slightly to increase visibility. NetMiner 4 was employed for data analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Start-Up

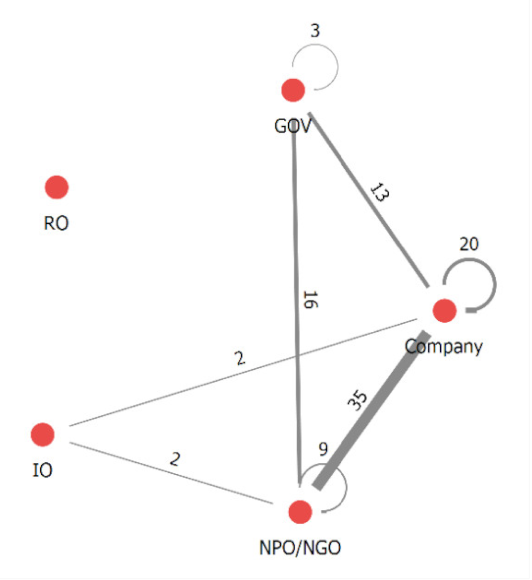

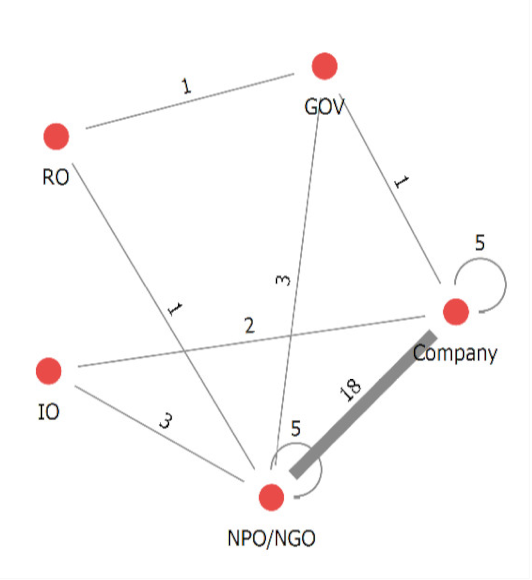

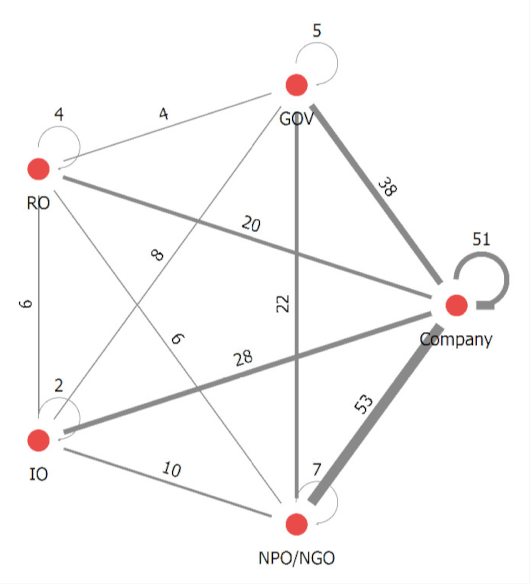

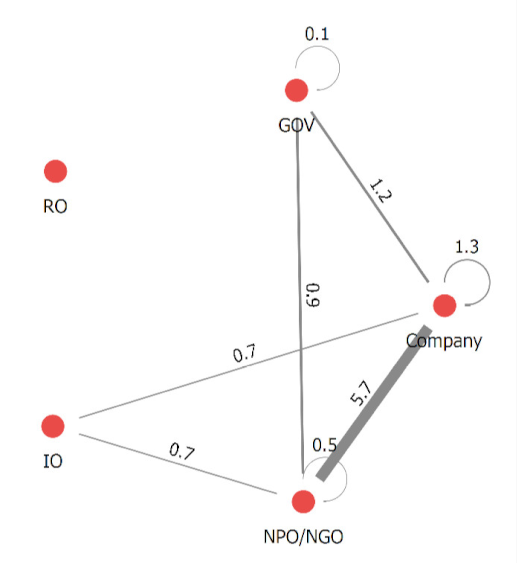

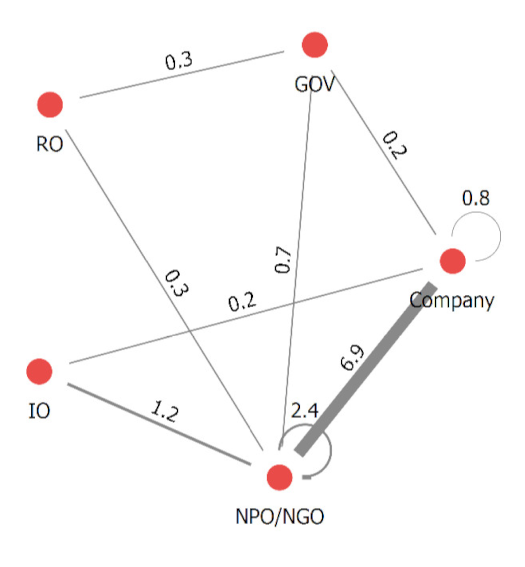

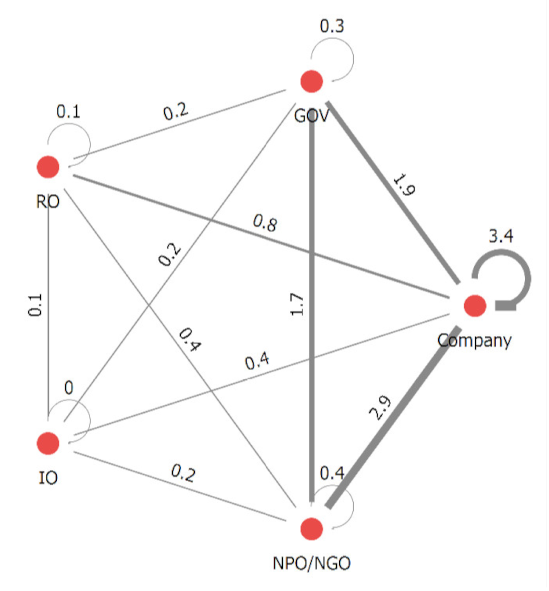

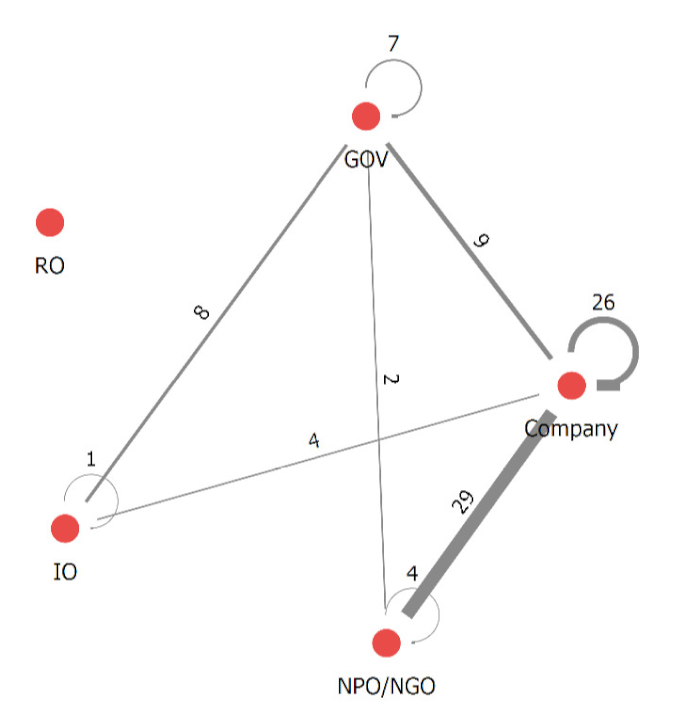

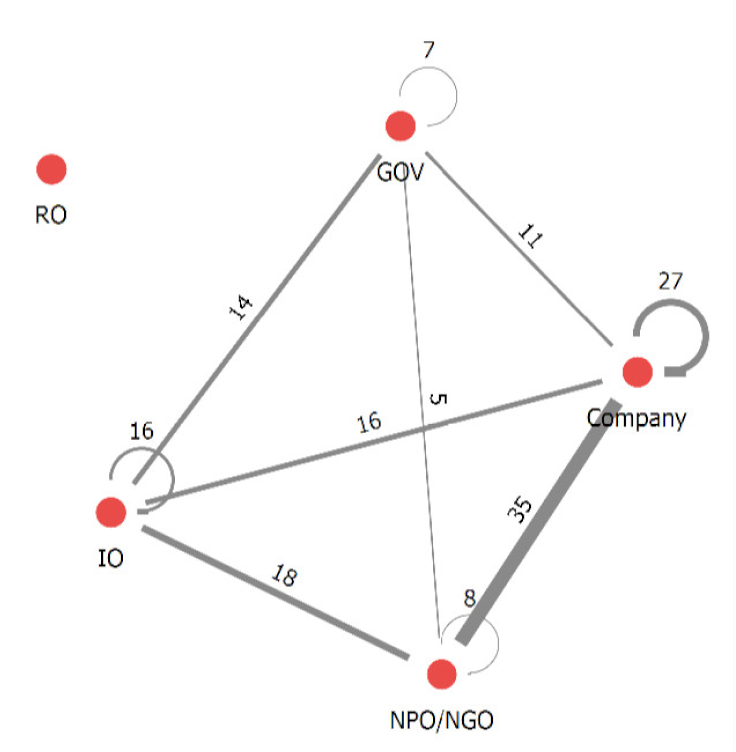

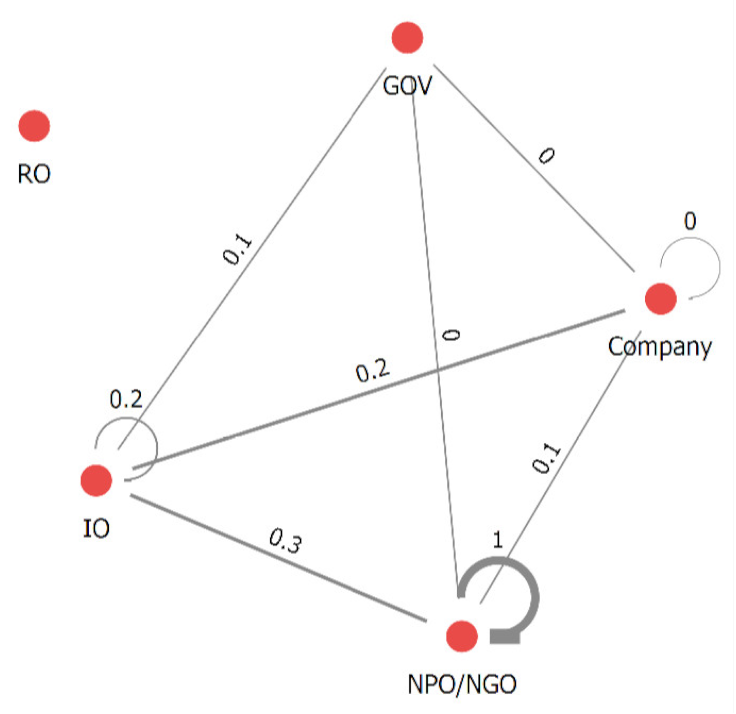

Regarding the investigation of the network relationship between stakeholders in P4G, Table 3 shows the network evolution of start-up projects from 2018 to 2020. The thickness of the line in the network indicates the strength of the connected entities. For instance, the partnership between company and NPO/NGO is strongest among P4G start-ups, according to the network of the sum. In 2018, no start-up projects were connected to RO, which connected to NPO/NGO and GOV in 2019 for the first time. The network connected to RO became much stronger in 2020, which include the connection to IO, company, and RO. Overall, the network between entities is diffused from 2018 to 2019. It means that, while the number of projects reduced in 2019, the network expanded.

Table 3.

Evolution of P4G start-up projects network (The projects network means that the visualization of inter-connections among stakeholders).

As the P4G platform for sustainable development evolves, the connection between GOV and company increasingly achieves the status of the most developed relationship. It indicates that the PPP is vitalized based on the P4G platform. Since the start-up projects have the characteristics of a pilot project and a base study, the participation of RO has been invigorated recently. Furthermore, in 2020, the cooperation between governments has also received a boost, which is evidence that P4G has been utilized as a platform and basis for bilateral and multilateral cooperation between multi-governments. The cooperation between companies has also become strong in 2020. Companies perceived the P4G start-up project as an opportunity for pilot projects, which generated interest in social values and responsibilities.

The summation network shows the extent to which entities participate in the P4G program. Thus, information on the number of projects is integrated with the number of entities. However, the normalized network indirectly presents the effectiveness of P4G start-up projects from a partnership network perspective. The sum of the number presented in the normalized network is equal to the number of projects in the year. It means that for the normalized network, we regard the weight of a project as 1. For example, if a P4G partnership consists of two RO, two company, and one IO, the partnership RO, company, and IO have weights of 0.4, 0.4, and 0.2 in the normalized network, respectively, while, in the summation network, they have 2, 2, and 1. Accordingly, the more stakeholders participated in a partnership, the lower the weight in the normalized network, as compared to the summation network.

The difference between the summation network (upper row) and the normalized network provides meaningful information. For instance, while the connections between GOV and NPO/NGO, on the one hand, and IO and company, on the other hand, are 22 and 28, respectively, in the 2020 summation network, it is 1.7 and 0.4 in the normalized network. The strength of the connections is inverted. Table 4 shows the difference in connection strength between the summation network and the normalized network. In 2020, the connection in the normalized network is stronger in the relationship between company, RO, and NPO/NGO and GOV and NPO/NGO. All connections with IO become small in the normalized network. It means that IO participated in projects consisting of multi-entity partnerships. This situation is evidence that IO plays a binding role in international cooperation businesses in bringing companies and governments together for sustainable development.

Table 4.

Difference in network strengths between the summation and normalized network.

Note: The network is a symmetric matrix. The negative value indicates that the entity tends to participate in projects with many participants.

4.2. Scale-Up

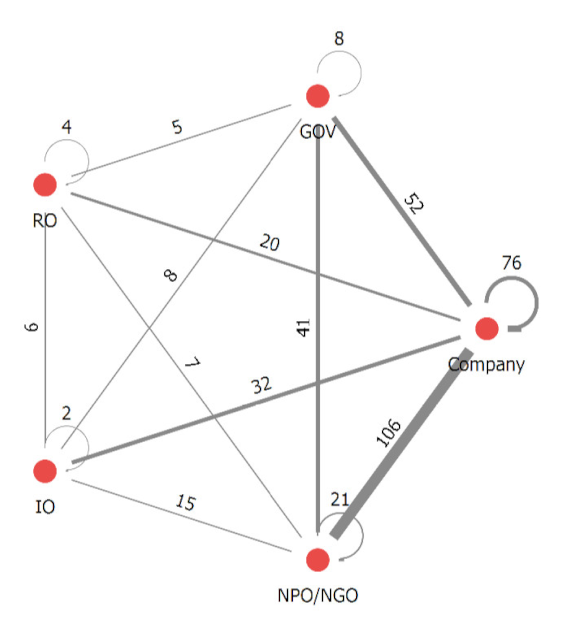

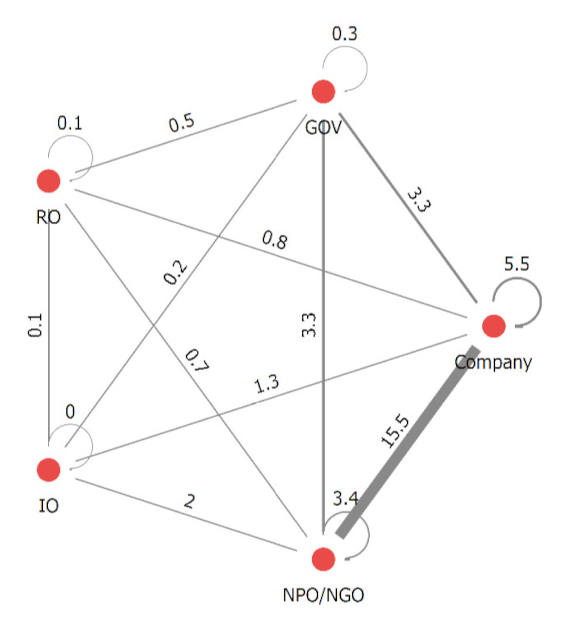

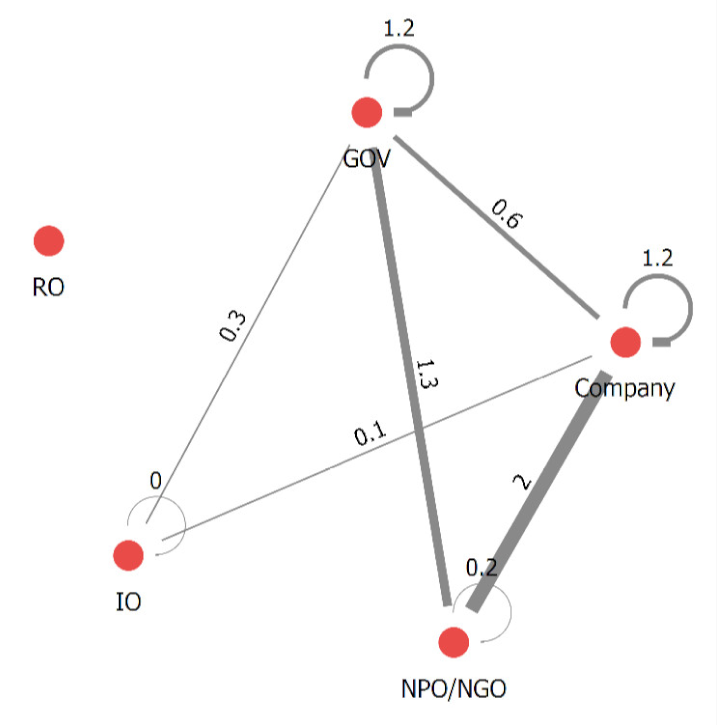

While the P4G start-up partnerships are eligible to be funded up to USD 100,000, the P4G scale-up partnerships are funded up to USD 1 million. Thus, P4G scale-up partnerships are more demonstrative. Currently, there are P4G scale-up projects for 2018 and 2019. Only two projects reached a scale-up status in 2018. The scale-up partnerships increased to seven projects in 2019. Table 5 shows how the networks around P4G scale-up projects evolved. Overall, the scale-up partnership has been unequally distributed yearly. In 2018, IO had the strongest network with entities except for RO. However, company had the strongest relationship in 2019.

Table 5.

Evolution of P4G scale-up projects network.

International organizations have participated in the P4G scale-up projects from the inauguration of the P4G platform. While the connections between international organizations are 15, in the normalized network, the strength is barely 0.2. This situation indicates that international organizations jointly participate in large-funded projects. Moreover, for any year, research organizations have not participated in P4G scale-up partnerships. This situation directly demonstrates the difference between start-up and scale-up partnerships. In the start-up stage, research organizations can assist in Research and Development (R&D) and pilot projects. However, the position of research organizations shrinks in the main demonstration project stage.

The movements of IO are noteworthy. In the start-up stage, IO has no strong relationship with itself and GOV. However, P4G scale-up projects present a different picture. At the start of P4G in 2018, IO has a strong relationship with itself. In addition, IO has developed its relationship with GOV further. From the P4G as a platform for international cooperation perspective, IO seemed to play the pioneering role of at the start of the platform. The phenomenon that IO has cooperated with GOV at the demonstrative project stage shows the importance of the role of IO in international business.

The main body of the network shifts from IO to company. Although the connection between company and IO was quite strong in 2018, as the role of IO became weak, the network between company and NPO/NGO, on the one hand, and company, on the other hand, became strong in 2019. Thus, for the P4G scale-up partnerships, company, as an entity pursuing profit, participated in the project. Given partnership development, the cooperation between GOV and company has become stronger. It also suggests that the P4G scale-up partnerships are heading toward PPP in accord with the P4G start-up partnerships.

The gap between a start-up and scale-up network is also remarkable. For instance, the role of RO in the network cannot be found in the scale-up network, even though many ROs have participated in P4G start-up projects. A reason can be, apart from lab-scale projects, RO has no strong point for a demonstrative project. In the middle of technology innovation (i.e., between lab-scale and demonstrative R&D) exists the valley of death, which can swallow the technology that is quickly commercialized to a demonstrative business from lab-scale R&D. However, RO can play a different role apart from R&D. It can inform the design of the business model for an international cooperation business since it can integrate different characteristics from other stakeholders to generate profit. Accordingly, as a player to design the business model and stimulate partnership, it seems that RO can be a major player in a P4G scale-up project.

The relationship between GOV and NPO/NGO of the normalized network is stronger than of the summation network in 2019. This situation is evidence that the cooperation between GOV and NPO/NGO does not include multilateral partnerships. In 2019, company participated in multilateral partnership projects consisting of the joint consortium of various companies. However, it seems bilateral rather than multilateral cooperation is the mainstream in the cooperation between governments since the network between governments is stronger in the normalized network.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Based on the previous findings, it is found that SDGs work in three perspectives: (1) The emergence of various development assistance actors, (2) the emergence of the development partnership that reflects various actors, and (3) financial resources that must fulfill SDGs and partnership implementation. In particular, to achieve SDGs globally, mobilizing new financing and development partners to lead the implementation beyond the existing ODA has been in the spotlight as a major implementation mechanism by various donors. Indeed, while the global ODA scale has increased, the size of private capital input into the development sector has also increased sharply since 2005. Moreover, in 2009, private development capital exceeds twice the total amount of ODA [38].

In other words, innovation to integrate technology and expertise of private and public sectors, as well as co-financing, will be required to achieve the SDGs. PPPs can provide public services and retain the generated profits. Furthermore, recipient countries of cooperation businesses can pursue sustainable development from the perspective of economic and social development. Advanced assistance institutions have run various PPP programs from a private perspective as a critical partner in international cooperation to improve development effectiveness. P4G supports the funding of projects to implement the Paris Agreement and achieve the SDGs. Thus far, over 50 partnerships are funded by the P4G for international development. In this regard, this study analyzed the partnerships in P4G by stage and year to present PPP implications in international development cooperation.

PPPs in P4G are diversified. Since PPPs create development cooperation through the diversification of financing and participants, P4G proceeds in the desirable direction. Regarding the P4G start-up network, while there is no participation of RO in 2018, the connection between GOV and NPO/NGO was advent in 2019. In 2020, IO and company have demonstrated meaningful cooperation with each other. It implies that for the PPP in international development cooperation, RO can play a crucial role in areas such as field study and commercialization at the start-up stage.

GOV and IO have no direct cooperation relationship in 2018 and 2019, unlike 2020. This result is evidence that governments have made efforts to achieve international society goals, such as SDGs. Moreover, the normalized network results of start-up partnerships show the decline of the role of IO, since IO assumes the adhesive role between company and GOV for partnerships consisting of various entities.

This study gives scope for implications regarding the promotion of PPP in collaborative international business. First, we visualized the evolution of PPPs via a case study of P4G, which is emerging as a promising cooperation platform to achieve SDGs. Second, from the results of network analysis, we defined the role of each stakeholder in the international cooperation business. Finally, future studies can consider respective stakeholders by comparing the network of R&D and demonstrative projects, as represented by the P4G start-up and scale-up stages, respectively.

Regarding the network results of scale-up partnerships, IO has a close relationship with GOV, NGO/NPO, and company, except for RO in 2018. Since the scale-up projects demand the grand scale fund, cooperation between international organizations is vitalized. Furthermore, cooperation between companies is also vitalized. It implies that companies focus on the demonstrative business for the profits at the scale-up stage. Otherwise, the situation can explain why research organizations do not participate in scale-up projects. The demonstrative commercialization at the scale-up stage places the priority on the investment and driving force of company rather than the role of RO. However, in the case where the role of company has continuously been emphasized, the sustainability of further business development can be threatened based on the PPP’s proper intention. Therefore, the potential for RO participation, which can propel commercialization in demonstrative projects, should be encouraged in the long-term. Regarding the implementation of the Paris Agreement, especially, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has emphasized the importance of technology transfer under the technology mechanism, as a technology transfer platform, such as that of the Climate Technology Center and Network. Research organizations may contribute to developing sustainable business models and solution research-based technology for climate mitigation.

As a result of the scale-up network analysis, international organizations in 2018 shows a close partnership with other participants except for research institutions (governments, NGOs/NPOs, and corporations). Cooperation among international organizations is also active due to the need for massive funding for scale-up projects.

Moreover, inter-enterprise cooperation is also notable, as substantial development projects by private companies are undertaken in scale-up projects, which, on the contrary, may explain the absence of the participation of research institutions in the scale-up phase. This situation is because private companies’ investment and business promotion are prioritized over the role of research institutions in the scale-up stage where practical commercialization takes place. However, the situation only highlighted the role of private companies; future developments can be difficult to ensure the sustainability of the business. Therefore, the commercial application of research that can be a boost for potential participants, as well as the participation of research institutions, are required. Regarding the implementation of the Paris Convention, as the UNFCCC highlights the technology mechanism, research institutions can provide practical solutions such as sustainable business models and technology-based solutions to address climate change.

Greenhouse gas reduction by achieving the SDGs under the Paris Agreement is a global agenda that should be achieved through joint efforts of the global community. PPP is meaningful in that it provides opportunities to achieve both public and private social development goals, as well as private business goals by simultaneously channeling public aid and private funds to achieving sustainable economic growth in developing countries.

However, to continue development cooperation projects through PPP, participants must exhibit balance and cooperation. As earlier demonstrated, the definition of PPP varies. However, the underlying concepts that constitute PPP are summarized as follows: (1) Inter-organizational relationship, (2) cooperation, (3) shared objectives, (4) risk-sharing (or allocation), and (5) mutual investments [3]. Thus, the balanced participation of five different participants in developing cooperation projects would be of great importance in managing risks and creating common interests through joint investments. Hence, the development of partnerships among PPP participants should be sought. Moreover, based on the development, it must be self-sustained by phased expansion from the start-up to scale-up stages.

Since public and private sectors have different objectives of existence and behavioral patterns, it is necessary to consider how to coordinate their interests, as well as how to establish a cooperative partnership with recipient countries where the public-private sector is integrated. In the case of governments that provide public funds for international development, they should consider not only the aspect of expanding scarce resources but also the long-term perspective when establishing PPPs. Regarding private sectors, they should consider publicity beyond activities that align with corporate social responsibilities to boost their social values and anticipate “sudden death,” given unexpected global challenges like COVID-19.

Meanwhile, companies should follow the same suggestions pertaining to governments and private sectors. Regarding NGO/NPO, efforts should be made to tackle the problem from the perspective of the recipient country. Regarding research institutions, it should be possible to support the establishment of basic data and strategic development. International organizations play a neutral role between various stakeholders, such as donor and recipient countries and public and private sectors. Meanwhile, it sets up the stage for the international community to prepare for initiatives to achieve SDGs. Thus, participants will have to work harder to attract more interest in their initiatives.

Achieving the SDGs and responding to climate change have been mainly addressed at the UN level. However, in recent years, the initiative is expanding to embrace international development cooperation between international organizations such as the World Bank and the European Union and individual countries. For example, the World Bank is promoting a “strategic framework on development and climate change” to developing countries to respond to climate change and discover related business opportunities. Moreover, the EU adopted the “Climate action and renewable energy package” legislation in April 2009 to seek joint action to counter climate change. In this context, as a platform outside the UN system, P4G is an initiative that emphasizes “action” based on a partnership with governments, businesses, and civil society. In addition, through PPP projects, P4G supports green growth, responds to climate change in developing countries, and aims to achieve SDGs. In other words, P4G aims to achieve the SDGs through innovative partnerships and promotes efficient business by making solutions that are developed in one region applicable to other regions. This study analyzes more than 50 projects conducted in the past three years through P4G from a partnership perspective. Furthermore, the results can help practitioners in establishing partnerships for international development projects for P4G or similar global cooperation platforms.

However, this study has limitations. Only a few PPP cases were analyzed because P4G has been launched for three years. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze more PPP cases in future research. In addition, to derive more practical PPP strategies, the donor and recipient countries of the participating entities, the size of the project, and the field of the sector should be investigated in more detail.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.C. and T.J.; methodology, G.C., T.J., Y.J., and S.K.L.; software, Y.J.; validation, G.C., T.J., and S.K.L.; formal analysis, G.C. and T.J.; investigation, G.C., T.J., and S.K.L.; resources, Y.J. and S.K.L.; data curation, G.C., T.J., Y.J., and S.K.L.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C., T.J.; writing—review and editing, G.C., T.J., Y.J., and S.K.L.; visualization, Y.J.; supervision, G.C., T.J., and S.K.L.; project administration, S.K.L.; funding acquisition, S.K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Green Technology Center Korea, project number C20223.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations. Trustee Council Chamber United Nations Headquarters the Role of Partnerships in the Implementation of the Post-2015 Development Agenda. In Proceedings of the The General Assembly and ECOSOC Joint Thematic Debate/Forum on Partnerships, New York, NY, USA, 9–10 April 2014; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Platform, U.S.K. Goal 17 Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=400&nr=2116&menu=35 (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Jomo, K.S.; Chowdhury, A.; Sharma, K.; Platz, D. Public-Private Partnerships and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Fit for Purpose? United Nations, Department of Economics and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abadie, R.; Howcroft, A. Developing PPPs in New Europe; PricewaterhouseCoopers: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cuttaree, V.; Mandri-Perrott, C. Public-Private Partnerships in Europe and Central Asia: Designing Crisis-Resilient Strategies and Bankable Projects; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The United Nations Foundation. Understanding Public-Private Partnerships; The United Nations Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Taskforce, P.G.B.T. Partnerships for Prosperity: The Private Finance Initiative; HM Treasury: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Forrer, J.; Kee, J.E.; Newcomer, K.E.; Boyer, E. Public-private partnerships and the public accountability question. Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 70, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partnerships, British Columbia. An Introduction to Public Private Partnerships; Partnerships, British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, E.; Fischer, R.; Galetovic, A. Public-Private Partnerships: When and How; University of Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, S.P. Public Private Partnerships: Theory and Practice in International Perspective; Routledge: Abington, UK, 2000; ISBN 9780415212687. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M.K. Risk Management in Public Private Partnerships, 12th ed.; Discussion Papers; Center for European, Governance and Economic Development Research: Göttingen, Germany, 2001.

- Kernaghan, K. Partnership and public administration: Conceptual and practical considerations. Can. Public Adm. 1993, 36, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrich, J.K.; Lewis, M.A.; George, G. Are public-private partnerships a healthy option? A systematic literature review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 113, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Huijstee, M.M.; Francken, M.; Leroy, P. Partnerships for sustainable development: A review of current literature. Environ. Sci. 2007, 4, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, L.K.; Funke, N.; Audouin, M.; Musvoto, C.; Nahman, A. The Sustainable Development Goals in South Africa: Investigating the need for multi-stakeholder partnerships. Dev. South. Afr. 2019, 36, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beisheim, M.; Liese, A. Transnational Partnerships: Effectively Providing for Sustainable Development? Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckstrand, K. Multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainable development: Rethinking legitimacy, accountability and effectiveness. Eur. Environ. 2006, 16, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkse, J.; Kolk, A. Addressing the Climate Change—Sustainable Development Nexus. Bus. Soc. 2012, 51, 176–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, M.; Dodds, F. Paper 3: High-quality Multi-stakeholder Partnerships for Implementing the SDGs; New World Frontier Publications: London, UK, 2016; Available online: http://newfrontierspublishing.com/all-papers/60-paper-3-high-quality-multi-stakeholder-partnerships-for-implementing-the-sdgs (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Colverson, S.; Hargeskog, S.-E.; Sweden, A. Harnessing the Power of Public-Private Partnerships: The Role of Hybrid Financing Strategies in Sustainable Development. Available online: http://docplayer.net/10028756-Harnessing-the-power-of-public-private-partnerships-the-role-of-hybrid-financing-strategies-in-sustainable-development.html (accessed on 25 April 2020).

- Lee, Y. A Study on the Official Development Assistance (ODA) and Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Projects of International Development Cooperation: UNDP and KOICA’s Practices. Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank SDGs and PPPs: What’s the Connection? Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/ppps/sdgs-and-ppps-whats-connection (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Marx, A. Public-Private Partnerships for Sustainable Development: Exploring Their Design and Its Impact on Effectiveness. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaraswamy, M.M.; Anvuur, A.M. Selecting sustainable teams for PPP projects. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Kumaraswamy, M.; Chung, J.; Wong, J. Identifying the critical success factors for relationship management in PPP projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, D.; Man, C. Toward Sustainable Development? A Bibliometric Analysis of PPP-Related Policies in China between 1980 and 2017. Sustainability 2018, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Wang, H.; Xiong, W.; Zhu, D.; Cheng, L. Public–private partnership as a driver of sustainable development: Toward a conceptual framework of sustainability-oriented PPP. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Smith, A.J. Sustainability Best Practice in PPP: Case Study of a Hospital Project in the UK. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/16414723.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Hueskes, M.; Verhoest, K.; Block, T. Governing public–private partnerships for sustainability: An analysis of procurement and governance practices of PPP infrastructure projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogai, Y.; Matsumura, Y.; Hoshino, Y.; Yasuda, T.; Ohkura, K. Centralized Business-to-Business Networks in the Japanese Textile and Apparel Industry: Using Network Analysis and an Agent-Based Model. J. Robot. Mechatronics 2019, 31, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaharudin, M.S.; Fernando, Y.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Sroufe, R.; Jasmi, M.F.A. Past, present, and future low carbon supply chain management: A content review using social network analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.J.; Park, J. Analysis of the partnership network in the clean development mechanism. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divjak, B.; Peharda, P.; Begicevic, N. Social network analysis of Eureka project partnership in Centeral and Soth-Eastern European regions. J. Inf. Organ. Sci. 2010, 34, 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, L. Effect of orgnisational position and network centrality on project coordination. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2009, 27, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streeter, C.L.; Gillespie, D.F. Social Network Analysis. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 1993, 16, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner-Burton, E.M.; Kahler, M.; Montgomery, A.H. Network analysis for international relations. Int. Organ. 2009, 63, 559–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Measuring Aid: 50 Years of DAC Statistics—1961–2011. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/MeasuringAid50yearsDACStats.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2020).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).