Consumers’ Behavior in Selective Waste Collection: A Case Study Regarding the Determinants from Romania

Abstract

:1. Introduction

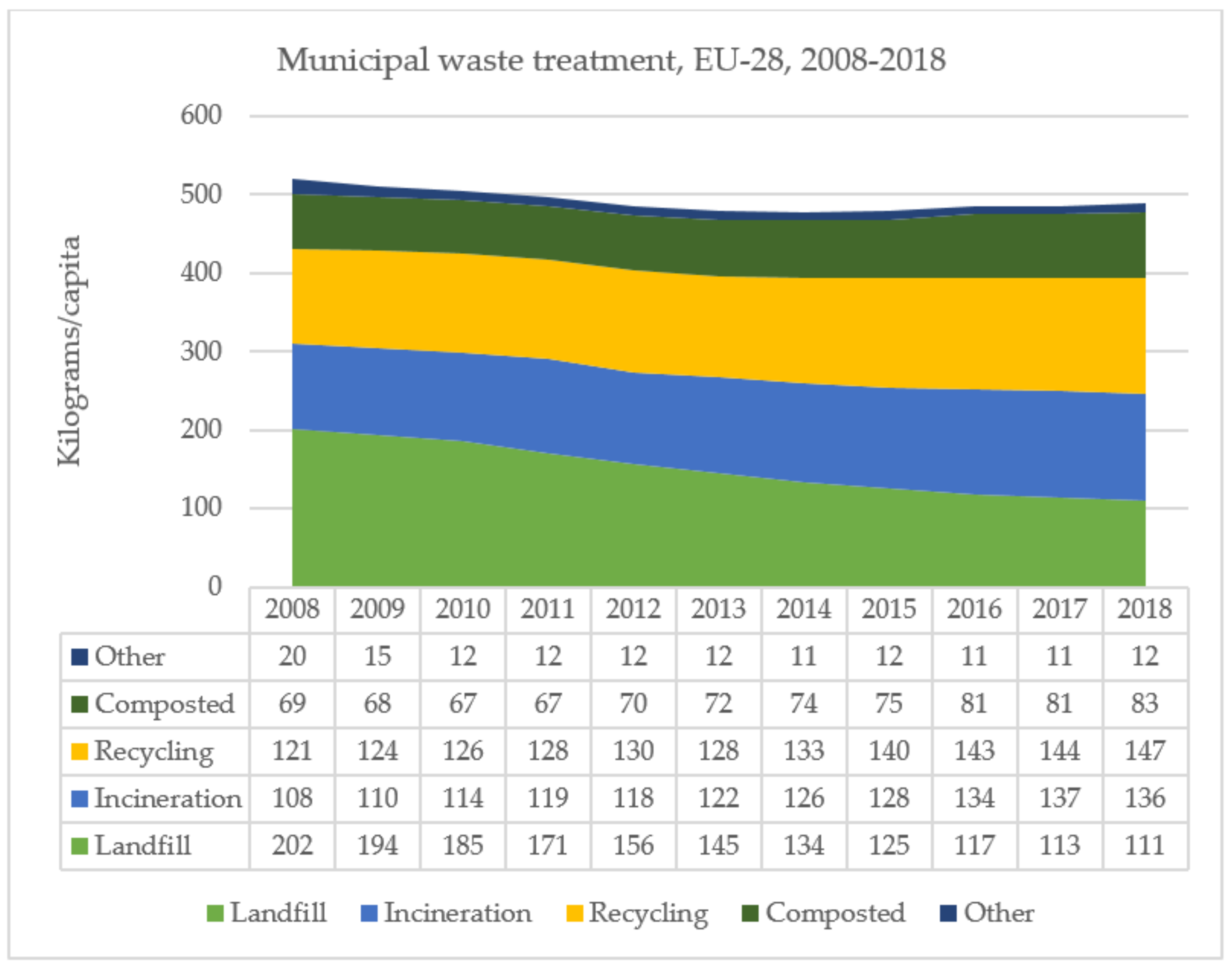

2. The Waste Situation in Romania

3. Literature Review

3.1. Research Variables

3.1.1. Social Norms

3.1.2. Social Media

3.1.3. Attitude

3.1.4. Perceived Behavioral Control

3.1.5. Intention

3.1.6. Convenience

3.1.7. Government Measures

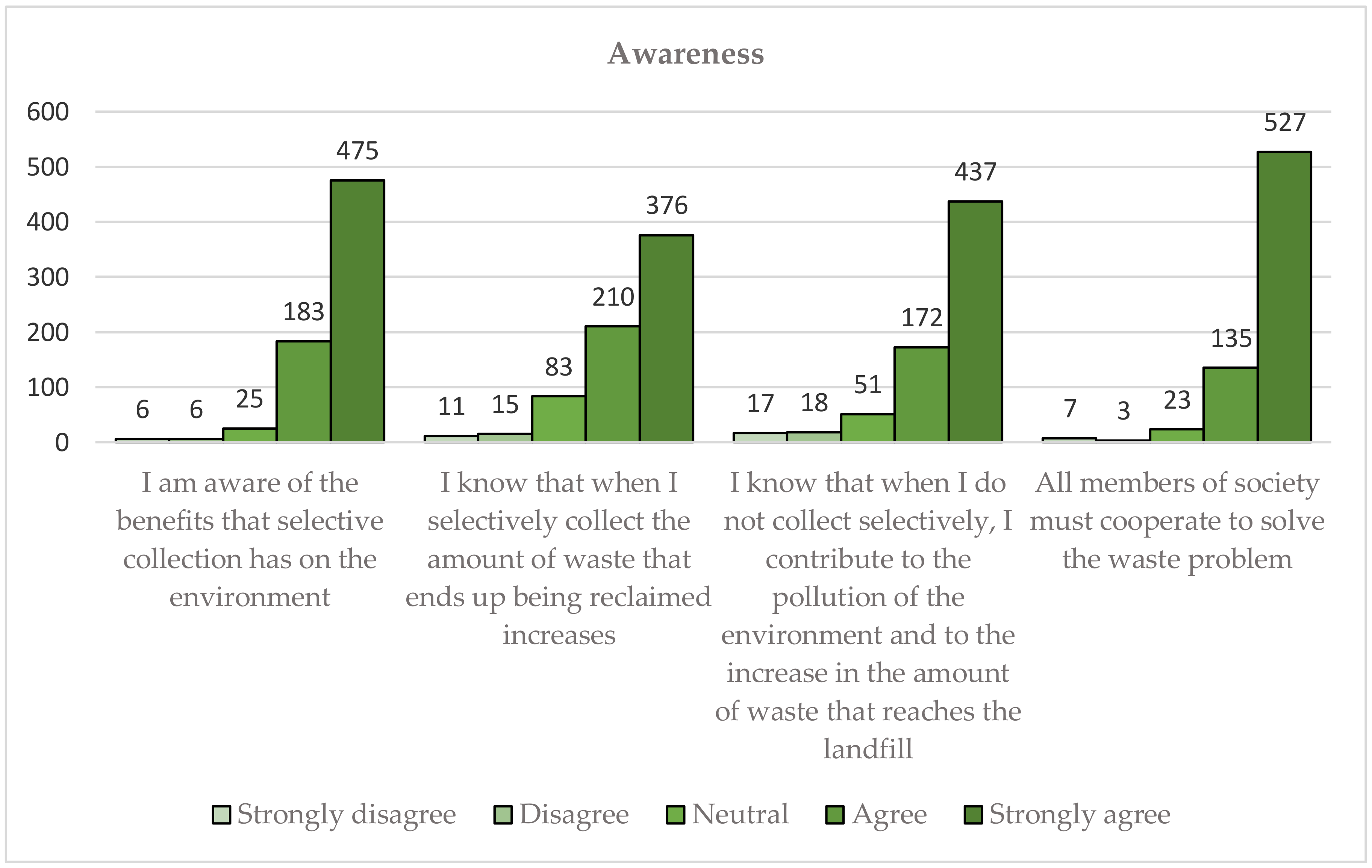

3.1.8. Awareness

3.1.9. Responsibility

3.1.10. Personal Norms

3.1.11. Trust

3.1.12. Environmental Knowledge

3.1.13. Collection Infrastructure

3.2. Research Methods and Tested Hypotheses

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Survey Design

4.2. Distribution

4.3. Questionnaire Analysis and Validation

4.4. Hypotheses

5. Case Study

5.1. Demographic and Socio-Economic Characteristics

5.2. Selective Collection Behavior

5.2.1. Attitude

5.2.2. Awareness

5.2.3. Environmental Knowledge

5.2.4. Waste Collecting Infrastructure

5.2.5. Perceived Behavioral Control

5.2.6. Selective Collection Behavior

5.2.7. Intention

5.2.8. Responsibility

5.2.9. Reward

5.2.10. Convenience, Government Measures, Social Norms and Taxation

5.3. Structural Model Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Research Questionnaire

| Issue | Acronym | Questions | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | AT | Selective collection is beneficial to society. (AT1) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I believe that when I collect selectively, I contribute to the protection of the environment. (AT2) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Selective collection reduces the amount of waste I produce. (AT3) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| I enjoy and it makes me feel good to collect selectively. (AT4) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Awareness | AW | I am aware of the benefits that selective collection has on the environment. (AW1) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I know that when I collect selectively, the amount of waste that ends up being reclaimed increases. (AW2) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| I know that when I do not collect selectively, I contribute to the pollution of the environment and to the increase in the amount of waste that reaches the landfill. (AW3) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| All members of society must cooperate to solve the waste problem. (AW4) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Perceived Behavioral Control | PBC | For me, selective collection is a difficult activity. (PCB1) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I know where to dispose the waste that I have selectively collected so that it can be recycled. (PCB2) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| The authorities provide enough containers to collect selectively. (PCB3) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Convenience | CON | Collecting selectively involves allocating the necessary space in the house. (CON1) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Selective collection requires time that I cannot allocate to this activity. (CON2) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Environmental Knowledge | EK | I know how to selectively collect correctly and what are the types of waste that can be recycled. (EK1) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I know that disposing of all the waste together can contaminate recyclable waste, making it impossible to recycle. (EK2) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| I know that storing waste on the ground can affect the groundwater and thus human health. (EK3) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Selective Collection Behavior | SCB | I separate all the waste I produce. (SCB1) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I do not collect selectively; I throw all the waste in the same container. (SCB2) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| I selectively collect the paper. (SCB3) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| I selectively collect plastic items. (SCB4) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| I selectively collect household appliances. (SCB5) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Government Measures | GM | If selective collection were mandatory, I would start collecting selectively. (GM1) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| If the trash that is not selectively collected wouldn’t be collected, I would start collecting selectively. (GM2) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| I believe that the application of strict laws on selective collection would lead people to engage in this process more. (GM3) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| If the sanitation fee were lower for the households who are selectively collecting, more households would engage in this activity. (GM4) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Intention | INT | I aim to selectively collect all the waste I produce, even if it is not always easy for me. (INT1) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I intend to actively participate in the selective collection initiatives promoted on social media. (INT2) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| I intend to buy only products whose packaging is 100% recyclable. (INT3) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| I intend to selectively collect all the waste I produce and reduce the amount of waste I generate annually. (INT4) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Waste Collection Infrastructure | INFR | In my opinion, collection centers must be properly managed. (INFR1) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I will selectively collect all waste if the authorities provided a modern collection infrastructure. (INFR2) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| I believe that collection centers must be close to homes. (INFR3) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Selective collection centers must not pose a danger to human health and must be kept in safe conditions. (INFR4) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Social Norms | SN | All the people who matter to me (family, friends and relatives) expect me to collect selectively. (SN1) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Neighbors and other community members will criticize me if I do not collect selectively. (SN2) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| If all the members of the community I belong to collect selectively, I will also start collecting selectively. (SN3) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Responsibility | RSP | I feel responsible to collect selectively to increase the amount of waste recovered. (RSP1) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I feel responsible for the amount of waste that I generate and that instead of being recycled, ends up in the landfill. (RSP2) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Reward | RW | I would be more likely to collect selectively if selective collection programs involved a financial reward. (RW1) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I would be more likely to collect selectively if I received a discount on the supermarket tax receipt for the packaging I return. (RW2) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Taxation | TAX | If I were charged double for the amount of waste I did not collect selectively, I would sort all the waste I produce. (TAX1) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| If I wouldn’t be charged extra for the amount of waste I don’t selectively collect, I wouldn’t sort all the waste I produce. (TAX2) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Appendix B. Answers Distribution for Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC), Convenience (CON), Selective Collection Behavior (SCB), Government Measures (GM), Intention (INT), Waste Collection Infrastructure (INFR), Responsibility (RSP), Reward (RW) and Taxation (TAX)

| Acronym | Questions ID | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCB | PCB1 | 213 (30.65%) | 208 (29.92%) | 157 (22.59%) | 79 (22.59%) | 38 (5.47%) |

| PCB2 | 67 (9.64%) | 100 (14.39%) | 119 (17.12%) | 196 (28.20%) | 213 (30.65%) | |

| PCB3 | 243 (34.96%) | 152 (21.87%) | 128 (18.42%) | 108 (15.54%) | 64 (9.21%) | |

| CON | CON1 | 45 (6.47%) | 51 (7.34%) | 132 (18.99%) | 239 (34.39%) | 228 (32.81%) |

| CON2 | 249 (35.83%) | 193 (27.77%) | 159 (22.88%) | 52 (7.48%) | 42 (6.04%) | |

| SCB | SCB1 | 38 (5.47%) | 124 (17.84%) | 174 (25.04%) | 205 (29.50%) | 154 (22.16%) |

| SCB2 | 290 (41.73%) | 180 (25.90%) | 93 (13.38%) | 75 (10.79%) | 57 (8.20%) | |

| SCB3 | 64 (9.21%) | 77 (11.08%) | 78 (11.22%) | 183 (26.33%) | 293 (42.16%) | |

| SCB4 | 42 (6.04%) | 40 (5.76%) | 76 (10.94%) | 182 (26.19%) | 355 (51.08%) | |

| SCB5 | 42 (6.04%) | 66 (9.5%) | 96 (13.81%) | 185 (26.62%) | 306 (44.03%) | |

| GM | GM1 | 60 (8.63%) | 60 (8.63%) | 145 (20.86%) | 130 (18.71%) | 300 (43.17%) |

| GM2 | 71 (10.22%) | 69 (9.93%) | 183 (26.33%) | 131 (18.85%) | 241 (34.68%) | |

| GM3 | 14 (2.01%) | 12 (1.73%) | 56 (8.06%) | 186 (26.76%) | 427 (61.44%) | |

| GM4 | 54 (7.77%) | 65 (9.35%) | 187 (26.91%) | 155 (22.30%) | 234 (33.67%) | |

| INT | INT1 | 13 (1.87%) | 26 (3.74%) | 136 (19.57%) | 252 (36.26%) | 268 (38.56%) |

| INT2 | 47 (6.76%) | 102 (14.68%) | 245 (35.25%) | 197 (28.35%) | 104 (14.96%) | |

| INT3 | 16 (2.30%) | 35 (5.04%) | 139 (20.00%) | 255 (36.69%) | 250 (35.97%) | |

| INFR | INFR1 | 7 (1.01%) | 4 (0.58%) | 35 (5.04%) | 183 (26.33%) | 466 (67.05%) |

| INFR2 | 20 (2.88%) | 30 (4.32%) | 87 (12.52%) | 183 (26.33%) | 389 (55.97%) | |

| INFR3 | 15 (2.16%) | 21 (3.02%) | 118 (16.98%) | 208 (29.93%) | 333 (47.91%) | |

| INFR4 | 11 (1.58%) | 6 (0.86%) | 26 (3.74%) | 158 (22.73%) | 494 (71.08%) | |

| RSP | RSP1 | 10 (1.44%) | 16 (2.30%) | 70 (10.07%) | 194 (27.91%) | 405 (58.27%) |

| RSP2 | 13 (1.87%) | 17 (2.45%) | 73 (10.50%) | 207 (29.78%) | 385 (55.40%) | |

| RW | RW1 | 105 (15.11%) | 171 (24.60%) | 204 (29.35%) | 118 (16.98%) | 97 (13.96%) |

| RW2 | 73 (10.50%) | 96 (13.81%) | 149 (21.44%) | 207 (29.78%) | 170 (24.46%) | |

| TAX | TAX1 | 66 (9.50%) | 72 (10.36%) | 161 (23.17%) | 141 (20.29%) | 255 (36.69%) |

| TAX2 | 194 (27.91%) | 149 (21.44%) | 217 (31.22%) | 77 (11.08%) | 58 (8.35%) |

References

- Rai, R.K.; Nepal, M.; Khadayat, M.S.; Bhardwaj, B. Improving Municipal Solid Waste Collection Services in Developing Countries: A Case of Bharatpur Metropolitan City, Nepal. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rai, R.K.; Bhattarai, D.; Neupane, S. Designing solid waste collection strategy in small municipalities of developing countries using choice experiment. J. Urban Manag. 2019, 8, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Statistics Eurostat—Recycling Rate of Municipal Waste. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/sdg_11_60/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 4 March 2019).

- Hansmann, R.; Bernasconi, P.; Smieszek, T.; Loukopoulos, P.; Scholz, R.W. Justifications and self-organization as determinants of recycling behavior: The case of used batteries. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2006, 47, 133–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Trends in Solid Waste Management. Available online: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/what-a-waste/trends_in_solid_waste_management.html (accessed on 11 July 2020).

- Lebreton, L.; Andrady, A. Future scenarios of global plastic waste generation and disposal. Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neagu, L. Minister of Environment Warns: Romania will Miss the 50% Target for Waste Recycling at the End of the Year and We Will Pay Penalties. Available online: https://www.green-report.ro/ministrul-mediului-avertizeaza-romania-va-rata-tinta-de-50-pentru-reciclarea-deseurilor-la-finele-anului-si-vom-plati-penalizari/ (accessed on 16 July 2020).

- Eurostat Municipal Waste by Waste Management Operations. Available online: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do (accessed on 16 July 2020).

- Romanian Government OUG 68 12/10/2016. Available online: http://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/182700 (accessed on 16 July 2020).

- Li, W.; Achal, V. Environmental and health impacts due to e-waste disposal in China—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 139745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZWN the Zero Waste Network. Available online: http://www.zerowastenetwork.org/ (accessed on 16 July 2020).

- ZWE European Zero Waste Municipalities—Compare European Cities’ Performance with Resource Recovery. Available online: http://zerowasteeurope.eu/zerowastecities.eu/city/107 (accessed on 16 July 2020).

- Boldero, J. The Prediction of Household Recycling of Newspapers: The Role of Attitudes, Intentions, and Situational Factors1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 25, 440–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés, C.; Lafuente, A.; Pedraja, M.; Rivera, P. Urban waste recycling behavior: Antecedents of participation in a selective collection program. Environ. Manag. 2002, 30, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonglet, M.; Phillips, P.S.; Read, A.D. Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to investigate the determinants of recycling behaviour: A case study from Brixworth, UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2004, 41, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, P.O.D.; Rebelo, E.; Reis, E.; Menezes, J. Combining Behavioral Theories to Predict Recycling Involvement. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 364–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, S.N.D.; Osman, K. The determinants of recycling intention behavior among the Malaysian school students: An application of theory of planned behaviour. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 9, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.; Paik, H.S. Korean household waste management and recycling behavior. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A.; Oppedal, I.O. General vs. domain specific recycling behaviour—Applying a multilevel comprehensive action determination model to recycling in Norwegian student homes. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, S.A.; Omar, M.S.; Bidin, Y.H.; Awang, Z. Environmental Problems and Quality of Life: Situational Factor as a Predictor of Recycling Behaviour. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 35, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bezzina, F.H.; Dimech, S. Investigating the determinants of recycling behaviour in Malta. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2011, 22, 463–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Yu, A. The role of perceived effectiveness of policy measures in predicting recycling behaviour in Hong Kong. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 83, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, F.; Ahmad, J.; Ambali, A.R. The Influence of Reward and Penalty on Households’ Recycling Intention. APCBEE Procedia 2014, 10, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, S.; O’Regan, B. Attitudes and actions towards recycling behaviours in the Limerick, Ireland region. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 87, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.P.; Zhu, D.; Le, N.P. Factors influencing waste separation intention of residential households in a developing country: Evidence from Hanoi, Vietnam. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, W.K.; Musa, N.D.; Hashim, N.H. Understanding Environmentally Friendly Consumer Behavior. In Regional Conference on Science, Technology and Social Sciences (RCSTSS 2014); Abdullah, M.A., Yahya, W.K., Ramli, N., Mohamed, S.R., Ahmad, B.E., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 909–921. ISBN 978-981-10-1456-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hynes, N.; Wilson, J. I do it, but don’t tell anyone! Personal values, personal and social norms: Can social media play a role in changing pro-environmental behaviours? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 111, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miliute-Plepiene, J.; Hage, O.; Plepys, A.; Reipas, A. What motivates households recycling behaviour in recycling schemes of different maturity? Lessons from Lithuania and Sweden. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 113, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Nomura, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Yabe, M. Model of Chinese Household Kitchen Waste Separation Behavior: A Case Study in Beijing City. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, M.; Yu, X.; Ren, H. What keeps Chinese from recycling: Accessibility of recycling facilities and the behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 109, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nduneseokwu, C.; Qu, Y.; Appolloni, A. Factors Influencing Consumers’ Intentions to Participate in a Formal E-Waste Collection System: A Case Study of Onitsha, Nigeria. Sustainability 2017, 9, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, H.; Lobo, A.; Dao, T. Encouraging Vietnamese Household Recycling Behavior: Insights and Implications. Sustainability 2017, 9, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pop, I.N.; de Ramírez, G.M.S.; Baciu, C.; Bican-Brișan, N.; Muntean, O.L.; Costin, D. Life cycle analysis in evaluation of household waste collection and transport in Cluj-Napoca, Romania. AES Bioflux 2017, 9, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Tan, X.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Z.; Tao, Y.; Qian, Y. Investigation on decision-making mechanism of residents’ household solid waste classification and recycling behaviors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, S. Procedural Information and Behavioral Control: Longitudinal Analysis of the Intention-Behavior Gap in the Context of Recycling. Recycling 2018, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strydom, W. Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior to Recycling Behavior in South Africa. Recycling 2018, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sujata, M.; Khor, K.-S.; Ramayah, T.; Teoh, A.P. The role of social media on recycling behaviour. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 20, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ng, S.-L. Predicting multi-family dwelling recycling behaviors using structural equation modelling: A case study of Hong Kong. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi Thu Nguyen, H.; Hung, R.-J.; Lee, C.-H.; Thi Thu Nguyen, H. Determinants of Residents’ E-Waste Recycling Behavioral Intention: A Case Study from Vietnam. Sustainability 2019, 11, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, B.; Ren, C.; Dong, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z. Determinants shaping willingness towards on-line recycling behaviour: An empirical study of household e-waste recycling in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 143, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamuk, S.; Kahriman-Pamuk, D. Preservice Teachers’ Intention to Recycle and Recycling Behavior: The Role of Recycling Opportunities. Int. Electron. J. Environ. Educ. 2018, 9, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Delcea, C.; Crăciun, L.; Ioanăș, C.; Ferruzzi, G.; Cotfas, L.-A. Determinants of Individuals’ E-Waste Recycling Decision: A Case Study from Romania. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halder, P.; Singh, H. Predictors of Recycling Intentions among the Youth: A Developing Country Perspective. Recycling 2018, 3, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delcea, C.; Popa, C.D.S.; Boloş, M. Consumers’ Decisions in Grey Online Social Networks. J. Grey Syst. 2015, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Delcea, C.; Cotfas, L.-A.; Trică, C.; Crăciun, L.; Molanescu, A. Modeling the Consumers Opinion Influence in Online Social Media in the Case of Eco-friendly Products. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.-C.; Chen, C.-W.; Tung, Y.-C. Exploring the Consumer Behavior of Intention to Purchase Green Products in Belt and Road Countries: An Empirical Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; SSSP Springer Series in Social Psychology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. ISBN 978-3-642-69746-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.-Y.; Chiu, J.-F. Factors Influencing Household Waste Recycling Behavior: Test of an integrated Model1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 33, 604–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Foxall, G.R.; Pallister, J. Beyond the Intention–Behaviour Mythology: An Integrated Model of Recycling. Mark. Theory 2002, 2, 29–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miafodzyeva, S.; Brandt, N. Recycling Behaviour Among Householders: Synthesizing Determinants Via a Meta-analysis. Waste Biomass Valorization 2013, 4, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.; Morgan, A. Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to determine recycling and waste minimisation behaviours: A case study of Bristol City, UK. Spec. Ed. Pap. 2008, 20, 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kite, J.; Gale, J.; Grunseit, A.; Li, V.; Bellew, W.; Bauman, A. From awareness to behaviour: Testing a hierarchy of effects model on the Australian Make Healthy Normal campaign using mediation analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Grob, A. A structural model of environmental attitudes and behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM. IBM SPSS Amos. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/ro-en/marketplace/structural-equation-modeling-sem (accessed on 6 March 2020).

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-317-63312-9. [Google Scholar]

- Spanos, Y.E.; Lioukas, S. An examination into the causal logic of rent generation: Contrasting Porter’s competitive strategy framework and the resource-based perspective. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 907–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcea, C.; Bradea, I.-A. Patients’ perceived risks in hospitals: A grey qualitative analysis. Kybernetes 2017, 46, 1408–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed.; Methodology in the social sciences; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4625-1779-4. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, D. Confirmatory Factor Analysis; Pocket guides to social work research methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-19-533988-8. [Google Scholar]

- Paswan, A.; D’Souza, D.; Zolfagharian, M.A. Toward a Contextually Anchored Service Innovation Typology. Decis. Sci. 2009, 40, 513–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-13-813263-7. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–40. ISBN 978-3-319-05542-8. [Google Scholar]

- Arcury, T.A.; Scollay, S.J.; Johnson, T.P. Sex differences in environmental concern and knowledge: The case of acid rain. Sex Roles 1987, 16, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladié, Ò.; Santos-Lacueva, R. The role of awareness campaigns in the improvement of separate collection rates of municipal waste among university students: A Causal Chain Approach. Waste Manag. 2016, 48, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffett, R.; Edu, T.; Haydam, N.; Negricea, I.-C.; Zaharia, R. A Multi-Dimensional Approach of Green Marketing Competitive Advantage: A Perspective of Small Medium and Micro Enterprises from Western Cape, South Africa. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Author | Determinants/Questions Referring to These Determinants Used in Research Papers * | Year | Country | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | |||

| Boldero [13] | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 1995 | Australia | ||||||||||||||

| Garces et al. [14] | x | x | x | 2002 | Spain | |||||||||||||||||||

| Tonglet et al. [15] ** | x | x | x | x | x | x | 2003 | United Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||

| Valle et al. [16] | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 2005 | Portugal | ||||||||||||||

| Mahmud and Osman [17] | x | x | x | x | 2010 | Malaysia | ||||||||||||||||||

| Lee and Paik [18] ** | x | x | 2010 | Korea | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Klöckner and Oppedal [19] | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 2010 | Norway | |||||||||||||||

| Latif et al. [20] ** | x | x | 2011 | Malaysia | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Bezzina and Dimech [21] ** | x | x | x | x | x | x | 2011 | Malta | ||||||||||||||||

| Wan et al. [22] ** | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 2014 | China | |||||||||||||||

| Amini et al. [23] | x | x | x | x | x | 2014 | Malaysia | |||||||||||||||||

| Byrne and O’Regan [24] ** | x | x | x | 2014 | Ireland | |||||||||||||||||||

| Nguyen et al. [25] ** | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 2015 | Vietnam | ||||||||||||||

| Yahya et al. [26] | x | x | x | 2016 | Malaysia | |||||||||||||||||||

| Hynes and Wilson [27] | x | x | x | 2016 | n.a. (Facebook) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Miliute-Plepiene et al. [28] | x | x | x | x | 2016 | Lithuania and Sweden | ||||||||||||||||||

| Yuan et al. [29] | x | x | x | x | 2016 | China | ||||||||||||||||||

| Zhang et al. [30] ** | x | x | x | x | 2016 | China | ||||||||||||||||||

| Nduneseokwu et al. [31] | x | x | x | x | x | x | 2017 | Nigeria | ||||||||||||||||

| Nguyen et al. [32] | x | x | x | x | 2017 | Vietnam | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pop et al. [33] ** | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 2015 | Romania | |||||||||||||||

| Meng et al. [34] ** | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 2018 | China | |||||||||||||

| Rosenthal [35] ** | x | x | x | x | 2018 | Singapore | ||||||||||||||||||

| Strydom [36] | x | x | x | x | 2018 | South Africa | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sujata et al. [37] ** | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 2019 | Malaysia | ||||||||||||||

| Ng [38] ** | x | x | x | x | 2019 | China | ||||||||||||||||||

| Nguyen et al. [39] | x | x | x | x | x | x | 2019 | Vietnam | ||||||||||||||||

| Wang et al. [40] | x | x | x | x | x | 2019 | China | |||||||||||||||||

| Pamuk and Kahriman-Pamuk [41] | x | x | x | x | 2019 | Turcia | ||||||||||||||||||

| Delcea et al. [42] | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 2020 | Romania | |||||||||||

| Model | NPAR | CMIN | DF | P | CMIN/DF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Default model | 201 | 3702.720 | 701 | 0.000 | 5.282 |

| Saturated model | 902 | 0.000 | 0 | ||

| Independence model | 82 | 15576.565 | 820 | 0.000 | 18.996 |

| Model | NFI Delta1 | RFI rho1 | IFI Delta2 | TLI rho2 | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Default model | 0.762 | 0.722 | 0.798 | 0.762 | 0.797 |

| Saturated model | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Independence model | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Model | RMSEA | LO 90 | HI 90 | PCLOSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Default model | 0.079 | 0.055 | 0.081 | 0.00 |

| Independent model | 0.161 | 0.181 | 0.163 | 0.000 |

| Model | NPAR | CMIN | DF | P | CMIN/DF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Default model | 104 | 421.078 | 171 | 0.000 | 2.462 |

| Saturated model | 275 | 0.000 | 0 | ||

| Independent model | 44 | 8534.238 | 231 | 0.000 | 36.945 |

| Model | NFI Delta1 | RFI rho1 | IFI Delta2 | TLI rho2 | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Default model | 0.951 | 0.933 | 0.970 | 0.959 | 0.970 |

| Saturated model | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Independent model | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Model | RMSEA | LO 90 | HI 90 | PCLOSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Default model | 0.046 | 0.040 | 0.051 | 0.886 |

| Independent model | 0.228 | 0.223 | 0.232 | 0.000 |

| AT | AW | EK | RSP | PBC | INFR | RW | INT | SCB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT1 | 0.830 | ||||||||

| AT2 | 0.833 | ||||||||

| AT3 | 0.467 | ||||||||

| AW1 | 0.849 | ||||||||

| AW2 | 0.702 | ||||||||

| AW3 | 0.740 | ||||||||

| AW4 | 0.809 | ||||||||

| EK2 | 0.832 | ||||||||

| EK3 | 0.827 | ||||||||

| RSP1 | 0.920 | ||||||||

| RSP2 | 0.810 | ||||||||

| PBC2 | 0.992 | ||||||||

| PBC3 | 0.437 | ||||||||

| INFR1 | 0.805 | ||||||||

| INFR4 | 0.791 | ||||||||

| RW1 | 0.918 | ||||||||

| RW2 | 0.720 | ||||||||

| INT1 | 0.878 | ||||||||

| INT2 | 0.655 | ||||||||

| SCB3 | 0.743 | ||||||||

| SCB4 | 0.817 | ||||||||

| SCB5 | 0.712 | ||||||||

| AVE | 0.534 | 0.604 | 0.688 | 0.751 | 0.588 | 0.637 | 0.681 | 0.600 | 0.575 |

| CR | 0.839 | 0.914 | 0.890 | 0.917 | 0.781 | 0.863 | 0.881 | 0.834 | 0.876 |

| Demographic and Socio-Economic Variables | Group/Components | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 554 | 79.71% |

| Male | 141 | 20.29% | |

| Age | ≤20 | 89 | 12.80% |

| 21–30 | 237 | 34.10% | |

| 31–40 | 234 | 36.67% | |

| 41–50 | 100 | 14.39% | |

| ≥51 | 35 | 5.04% | |

| Educational level | Secondary education | 16 | 2.30% |

| High school education, lower cycle | 24 | 3.45% | |

| High school education, upper cycle | 190 | 27.34% | |

| Post-secondary education | 18 | 2.60% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 223 | 32.09% | |

| Master’s degree | 202 | 29.07% | |

| PhD | 22 | 3.15% | |

| Residential area | Urban | 565 | 81.71% |

| Rural | 130 | 18.29% | |

| Marital status | Single | 380 | 54.67% |

| Married | 284 | 40.87% | |

| Divorced | 31 | 4.46% | |

| Occupation | Student | 206 | 29.64% |

| Employed in the public sector | 80 | 11.51% | |

| Employed in the private sector | 274 | 39.42% | |

| Entrepreneur | 51 | 7.34% | |

| Freelancer | 34 | 4.89% | |

| Others | 50 | 7.20% | |

| Family size | 1–2 persons | 321 | 46.19% |

| 3–4 persons | 317 | 45.61% | |

| ≥5 persons | 57 | 8.2% | |

| Income | ≤280€ | 171 | 24.60% |

| 281–400€ | 73 | 10.50% | |

| 401–750€ | 139 | 20.00% | |

| 751–1000€ | 150 | 21.57% | |

| 1001–1500€ | 85 | 12.22% | |

| >1500€ | 78 | 11.01% | |

| Number of years in e-waste recycling | Do not practice | 196 | 28.20% |

| ≤1 year | 166 | 23.88% | |

| 2–3 years | 202 | 29.06% | |

| 4–5 years | 60 | 8.64% | |

| ≥6 years | 71 | 10.22% | |

| Most frequently used social media | 430 | 61.87% | |

| 8 | 1.15% | ||

| 222 | 31.95% | ||

| 14 | 2.01% | ||

| Others | 21 | 3.02% |

| Hypotheses | Relationship | Decision |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Attitude → Intention | Not supported |

| H2 | Reward → Intention | Supported + |

| H3 | Perceived Behavioral Control → Intention | Supported *** |

| H4 | Environment Knowledge → Intention | Not supported |

| H5 | Responsibility → Intention | Supported *** |

| H6 | Waste Collection Infrastructure → Intention | Supported *** |

| H7 | Awareness → Selective Collection Behavior | Supported ** |

| H8 | Intention → Selective Collection Behavior | Supported *** |

| Hypotheses | Relationship | Gender | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | ||

| H1 | Attitude → Intention | Not supported | Not supported |

| H2 | Reward → Intention | Supported + | Supported * |

| H3 | Perceived Behavioral Control → Intention | Supported *** | Supported *** |

| H4 | Environment Knowledge → Intention | Not supported | Not supported |

| H5 | Responsibility → Intention | Supported *** | Supported *** |

| H6 | Waste Collection Infrastructure → Intention | Supported *** | Supported *** |

| H7 | Awareness → Selective Collection Behavior | Supported ** | Supported * |

| H8 | Intention → Selective Collection Behavior | Supported *** | Supported *** |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jigani, A.-I.; Delcea, C.; Ioanăș, C. Consumers’ Behavior in Selective Waste Collection: A Case Study Regarding the Determinants from Romania. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6527. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166527

Jigani A-I, Delcea C, Ioanăș C. Consumers’ Behavior in Selective Waste Collection: A Case Study Regarding the Determinants from Romania. Sustainability. 2020; 12(16):6527. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166527

Chicago/Turabian StyleJigani, Adina-Iuliana, Camelia Delcea, and Corina Ioanăș. 2020. "Consumers’ Behavior in Selective Waste Collection: A Case Study Regarding the Determinants from Romania" Sustainability 12, no. 16: 6527. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166527

APA StyleJigani, A.-I., Delcea, C., & Ioanăș, C. (2020). Consumers’ Behavior in Selective Waste Collection: A Case Study Regarding the Determinants from Romania. Sustainability, 12(16), 6527. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166527