1. Introduction

Developing environmental literacy (EL) is fundamental for dealing with the pressing environmental challenges we face in today’s world. Much research on developing EL focuses on students and teachers in formal education settings, such as assessment of students’ EL skills [

1,

2,

3], students’ attitudes [

4,

5], awareness [

6] and behaviours [

7], as well as teachers’ perceptions of environmental education [

8]. Few studies, however, have highlighted the role parents play in socialising children into environmentally responsible individuals. For example, how do parents involve their children in everyday decisions regarding reduction of energy consumption? What do parents do to (dis)encourage their children to respect nature? What is the efficacy of the parents’ engagement with their children? This exploratory study sets out to examine how parents engage with their children with regard to EL development. In particular, it investigates how confident parents feel (efficacy) in their own environmental awareness, and whether their efficacy has an effect on their engagement with their children. It further explores whether levels of parental engagement and their confidence are affected by other factors, such as the family’s socio-economic status (SES), parents’ age, or children’s age.

China is one of the most polluting countries in the world [

9]. Although the government has implemented various regulations and introduced strong enforcement tactics to reduce toxic emissions and encourage recycling, little is known about how grassroots initiatives and private households are dealing with these environmental challenges in everyday life. Moreover, since China has the world’s largest population (>1.39 billion people), any grassroots initiative would have significant implications for protecting the environment. Parents play an active role in modelling their children’s behaviour in private domains and have a vital influence on their children’s pro-environmental behaviour and awareness [

10,

11]. In this regard, it is vital to study how parents socialise their children into understanding the impact of high energy consumption, climate change, and the loss of biodiversity on their everyday life. Most importantly, children learn from observations and experiences. These direct and implicit learning experiences can build positive attitudes, develop environmental values, and cultivate efficacy. Parents’ active involvement and direct engagement with their children, thus, can lead to social and environmental changes.

2. Literature Review: Environmental Education, Parental Engagement, and Socialisation

Research in environmental education has stressed the importance of developing environmentally literate citizens [

2,

12,

13]. Becoming environmentally literate entails a process of acquiring environmental knowledge, having positive attitudes, and obtaining cognitive skills to solve environmental problems. It also entails a process of cultivating responsible behaviour patterns to protect the environment [

14,

15,

16]. In our study, EL, thus, includes knowledge of the environment and ecology, attitudes towards environmental issues, skills and strategies for solving problems, and, finally, active participation/behaviour patterns in protecting the environment.

Research into EL shows that knowledge about the local ecology, socio-political system, and the causes of environmental problems and issues is a crucial factor for making well-informed decisions about one’s behaviour and actions [

3,

13,

17]. Kuthe et al. (2019), for example, conducted a comparative study of the young German and Austrian generation’s awareness of climate change. By involving 760 youths through a questionnaire, they found that these young people have a relatively low level of knowledge about scientific facts. In a similar vein, Chu and his colleagues (2007), in their study of year-three schoolchildren in Korea, also found a low level of knowledge about the local ecology and the relationship between humanity and nature. Similar findings have also been reported in other parts of the world [

1,

2,

3].

Although knowledge is an important component of EL, research shows that there can be a gap between knowledge and attitudes and knowledge and behaviour [

5,

18,

19,

20]. Liefländer and Bogner’s (2018) study of German school children suggests that there is no correlation between environmental knowledge and children’s attitudes within the framework of an environmental intervention programme. Clayton and her colleagues (2019) studied EL and nature experience of different age groups of children and adults in China; they reported that knowledge about environment and nature increased with age, while environmental concerns decreased. While younger children were very positive about nature and the need to protect it, their knowledge about environmental protection was moderate. With regard to the adult group, their knowledge about nature and conservation was associated with intent to protect nature, but not with actual sustainable behaviour. Similarly, Negev et al. (2008) studied Israeli elementary and secondary schoolchildren’s level of EL. Their findings suggest that while there was a strong correlation between attitudes and knowledge, there was negative correlation between environmental behaviour and knowledge. Arnon et al. (2015) [

21], in their study of college students in Israeli, also found that the general level of environmental values and attitudes was high, but the level of environmental knowledge was low, and so was the pro-environmental behaviour.

While the studies reviewed above highlight the importance of an educational pathway for dealing with the current environmental crisis by implementing or updating educational programmes and curricula, it is vital not to overlook the impact of parents on the process of knowledge learning and behaviour formation [

22]. Parents, as the primary socialisation agents, can have profound influence on their children’s beliefs, values, attitudes, and behavioural patterns in the early years [

23,

24]. Research on intergenerational transmission of pro-environmental practices, however, has been limited, and little has been done concerning parents’ engagement with their children in this regard.

The limited number of studies on intergenerational transmission of EL have mainly focused on environmental attitudes and behavioural patterns. Grønhøj and Thøgersen (2009) [

25] for instance, studied 601 families in Denmark, where they explored parent–children (adolescents) similarities in three common household practices: Purchasing environmentally friendly products, curtailing electricity use, and handling waste. The findings indicate that the correlation between parent and child attitudes was strong for buying organic and environmentally friendly products, weak for saving electricity, and medium for the source separation of waste. The study suggests that family socialisation exerts a significant influence on children’s pro-environmental orientation. Likewise, Leppänen et al. (2012) studied parent–child similarity in environmental attitudes in Finland. In this pairwise study involving 237 schoolchildren (15 years old) and 212 parents, the researchers found a significant, positive correlation between mothers and fathers. Parents’ environmental attitudes were also related to the children’s attitudes. The above reviewed studies and other research projects indicate that family socialisation is more pronounced when children are younger [

10]. However, when children become older, other socialisation agents, such as media, teachers, and peers, may have more influence. Despite the external factors, behavioural patterns formed in childhood can have a long-lasting effect, regardless of the generation gap in the environmental attitudes.

Stern et al. (2018) [

26] investigated children’s environmental behaviour patterns and responsibility from a role model perspective. The study involved 5498 middle school students in a residential centre of environmental education in the United States (US). Although the students were in identity transition from children to adolescents, and despite the fact that the students attended the environmental education programme, they identified their parents as strong role models in their development of environmentally responsible behaviour. The parental role is also evident in studies of children’s knowledge and awareness of energy literacy, carbon dioxide reduction, and climate change [

10,

27,

28,

29].

Aguirre-Bielschowsky and colleagues (2017) conducted a qualitative study in New Zealand by interviewing year-five schoolchildren (9–10 years old,

n = 26) and their parents (

n = 26) through focus group discussions. The study aimed to investigate children’s energy literacy regarding electricity production, energy consumption, and their consequences. With regard to children’s knowledge about energy, they reported that the source of learning was largely informal and mostly from family talk. While the children were aware of the importance of electricity and energy in modern life, they were not able to identify any method of energy generation, such as coal, gas, or geothermal energy generation, neither were they able to identify the sources of climate change. Parents admitted that they had provided inadequate information on how and only superficial justification for why to save power, as they were concerned about their children’s cognitive ability to understand complex energy-related issues, such as the relationship between electricity production, consumption at home, and environmental problems. They also admitted struggling to explain these issues because of their own lack of knowledge. With regard to affect, children showed generally weak positive attitudes towards saving power. The small number of children who “displayed an environmental identity and understood the relationship between the environment and energy consumption” [

10] were influenced by parents who themselves expressed strong environmental convictions and lifestyles and very often talked about environmental issues.

The studies above illustrate the strong connections between children and parents in terms of knowledge about environmental issues and corresponding behavioural patterns. The findings suggest that in-depth conversations about energy issues are a critical knowledge source and socialisation mechanism that can lead to pro-active behaviours and positive attitudes. These studies point out the importance of parents’ efficacy in their environmental engagement with their children [

30,

31]. Our study addresses these important aspects of parental engagement by answering the following research questions:

What are the levels of parental engagement with environmental literacy in China?

What is the relationship between this engagement and parents’ efficacy beliefs for environmental literacy?

Are there any factors that are related to environmental literacy, such as children’s age, parent’s age, or family socio-economic status (SES)?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

We recruited participants through an online invitation sent to families in our social networks. Thereafter, potential participants were contacted through the method of snowballing. Recruiting criteria included that families have at least one child between 5 and 12 years of age, as this age group of children tends to be strongly influenced by families [

22,

24]. In total, 368 eligible participants answered an online questionnaire. Of these, 267 were mothers, 83 fathers, while a further 12 were grandparents (eight grandmothers, four grandfathers), and six individuals were ‘other female carers’. The participants were aged between 22 and 62 years, with a mean age of 37.3. The largest group of the participants were in the 35–39 age bracket (close to 40%), followed by those aged 40–44, who constituted almost a quarter of the sample, and then those in their early thirties, who added just over 20% to the sample. Their education level ranged from pre-primary to postgraduate, with over 80% of participants having some education beyond secondary school level (see

Table 1 for more details about education and age of the participants).

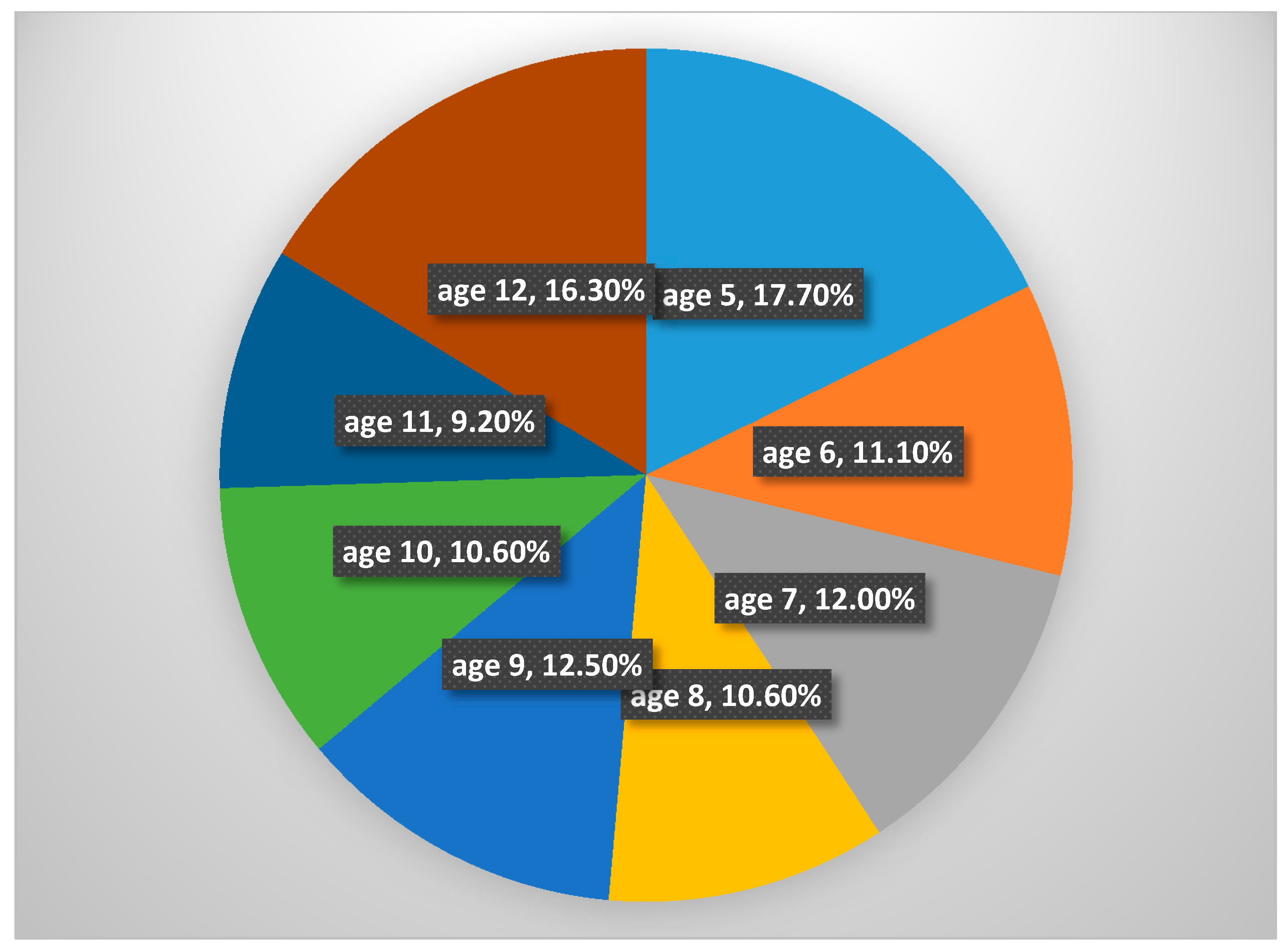

With regard to children’s age, there was a good spread of ages reported, as can be seen from

Figure 1 below. While there were some differences in numbers, none of the age groups were particularly underrepresented. A total of 197 participants had a male child, whereas 171 had a female child.

3.2. Questionnaire

The questionnaire was prepared in English and then translated into Chinese. To ensure the quality of translation, it was translated by four individuals. When a term emerged with different translations, the authors consulted with publications and online sources to identify the correct terminology in Chinese. A final version was based on a combined translation after a pilot had been conducted.

The questionnaire included four sections: (1) Information sheet and consent form, (2) section about the child, (3) section about EL, and (4) section about the parent. The first section contained information about the study, the participants’ rights, and their consent to participating in the study. As the study is about parents’ and carers’ interactions with children, the participants were asked to think about a specific child when answering the individual items. Hence, in the second part, information about this child was collected, including child’s age, gender, school year, and personal possessions.

Section 3, the main section, included 48 items reflecting four components of EL, including knowledge, skills, affect, and behaviour [

15,

16]. In order to find out whether the parents felt competent in explaining environmental issues and to address the gap in the field, we also included five items that tapped into the parents’ efficacy in engaging with their children about EL. These included items such as “I feel confident that I can teach my child about the environment”, “I feel confident that I understand the relationship between environment and society”, etc. The participants responded to these questions by using a six-point Likert scale (6 strongly agree, 5 agree, 4 somewhat agree, 3 somewhat disagree, 2 disagree, 1 strongly disagree).

In the final section, parents and carers were asked to provide relevant biodata about themselves, including their age, relation to the child, education and job level, and a list of household items (computer, air conditioner, smart TV, etc.). These data, alongside the data on their child’s personal possessions from

Section 2, provided the information necessary to establish the family’s SES background.

3.3. Procedures and Data Analysis

All the items were translated into Chinese and piloted with a small group of Chinese parents. They were asked to point out unclear items, suggest modifications, and even add on new items to the existing pool. The questionnaire was then uploaded to onlinesurveys.ac.uk and screened for errors before it was sent to the participants. The participants were encouraged to share the link with other parents and caregivers. Therefore, the data were collected through the snowball sampling method.

We conducted statistical analysis of data by employing SPSS. The analysis involved the initial screening of data for errors to ensure data quality. Following that, exploratory factor analysis (Maximum Likelihood, Direct Oblimin Rotation) was used to ascertain if there were any meaningful factors on EL in the dataset. Further analysis involved counting Cronbach’s alpha to establish reliability, and correlational analysis to investigate the relationships between variables. Principal components analysis was used to obtain an index of SES, and correlation analysis was subsequently used to examine whether SES, as well as its two main components, parental education and parental job level, were related to levels of EL. Similarly, correlations were also used to determine if the child’s age was in any relation to parental talk and encouragement with regards to EL.

4. Results

4.1. Aspects of Environmental Literacy and Efficacy

In factor analysis, four factors related to environmental literacy were identified, i.e., knowledge and understanding, affect, consumption-related behaviours, and nature protection behaviours. Additionally, the structure of parental efficacy beliefs about EL was confirmed. The reliability of the scales was high, ranging from 0.88 for the consumption-related behaviours to 0.96 for knowledge and understanding. In the following, we first present the results of the study by describing these five factors, and then report on the analysis of the relations between these factors and demographic variables. Further statistical details of the scales from factor analysis, including final item numbers and reliability, can be found in

Table 2.

Knowledge and understanding: Items on this scale touched upon key information about the environment and the interaction of different components of the environment that parents discussed with their children. Example: I explain how animals survive in nature.

Affect: Items on this scale aimed to reflect parents’ conversations and discussions with their child to instil concern about and responsibility for the environment, and to show that humans are also dependent on the environment. Example: I read to my child stories that show how important nature is.

Consumption-related behaviours: Behaviours encouraged by parents that are related to everyday life choices, particularly consumptionism. Example: I encourage my child not to use disposable bowls and chopsticks.

Nature protection behaviours: Behaviours encouraged by parents and which are related to protecting nature and saving resources. Example: I encourage my child not to damage plants.

Parental efficacy beliefs about environmental literacy: Parental beliefs about their own ability to pass on environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours to their children. Example: I feel confident that I can teach my child about the environment.

As can be seen in

Table 2, the participants reported very high levels of engagement with issues related to developing their children’s EL, with all the means oscillating between 5 and 6, indicating agreement or strong agreement with the statements included in the scales. In particular, it can be seen that parents encourage behaviours that are related to nature protection, such as saving water or not damaging plants. For this particular factor, a quick glance at the standard deviation shows that there is generally little variation in parents’ responses, with an overwhelming majority of participants choosing ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’ as answers to the individual statements. As such, these behaviours appear to be almost universally endorsed by the participants. Parents also declared that they draw their children’s attention to the role of humans on Earth and the responsibility that comes with it, i.e., environmental affect. In contrast, the lowest score on scales for EL, albeit still very high, was found on the scale for knowledge and understanding. This scale also had more variation in responses than other scales related to engagement with EL, namely 0.62. Even that, however, suggests that the participants tended to pass on key facts about the environment to their children in informal conversations.

The average score on the scale for parental efficacy beliefs about environmental literacy was the lowest on all scales, showing the highest degree of variation. However, this result still points to a high confidence in beliefs about passing on environmental knowledge and skills and instilling responsibility for most of the population, and to a moderate confidence for a small proportion of respondents.

4.2. Correlations

The factors were all strongly or moderately correlated. From

Table 3 can be seen that the parental efficacy beliefs were more closely related to the cognitive aspects of EL, i.e., knowledge and understanding (Pearson correlation = 0.845, p. = 0.000), than to the more affective (Pearson correlation = 0.669, p. = 0.000) and behavioural components. There was also a difference between the two factors indicating behavioural aspects of EL, in that behaviours related to consumption (Pearson correlation = 0.762, p. = 0.000) were more strongly related to parents’ efficacy beliefs than those related to nature protection (Pearson correlation = 0.583, p. = 0.000).

Correlation analysis showed that the levels of engagement with EL were not related to children’s age. The parents’ age, however, was inversely correlated, even though this correlation was weak regarding levels of knowledge and understanding as well as consumption-related behaviours. This means that the younger the parents, the higher the engagement with these topics in their interactions with their children.

Furthermore, correlational analysis revealed a significant relationship between only one aspect of EL and SES, namely consumption-related behaviour; this relationship was negative and the correlation was weak (see

Table 3 for further details). This points to the pattern that parents with lower SES were declaring higher levels of environmentally friendly consumer choices, such as avoiding buying products in excessive packaging, or encouraging their children to use public transport or walk, rather than choosing to go by car.

When looking at the influence of the two major components of SES, a similar pattern can be seen. When job level was concerned, as with the composite SES score, there was only one significant correlation, namely with consumption-related behaviours, and it was also inverse and weak. This means that parents with higher job levels tended to report slightly lower levels of engagement with issues to do with environmentally friendly consumption and travel choices.

There were more significant correlations with parental education level than with the job level or the composite score for SES, although all of them were weak. In all cases, the direction of the relationship was negative, meaning that with higher parental education level, the scores on the variables tended to be lower. Apart from the consumption-related behaviours, parents with lower levels of education tended to report more talk with their children about relevant environmental knowledge and understanding, and they also felt slightly more confident about their ability to pass on environmental knowledge, instil desired environmental attitudes, and inculcate environmentally friendly behaviours than more educated parents did.

From these results, we can infer that parents’ level of education was more closely related to their engagement in EL than the compositive SES factor or the job level. Of all factors, consumption-related behaviours and knowledge and understanding were most sensitive to the influence of age and SES-related factors. Considering the complexity of family socialisation patterns, we discuss below how parents as agents interact with the different factors when socialising their children into becoming environmentally conscious citizens.

5. Discussion

The current study yields three preliminary but important findings: There are (1) a high level of engagement with children in general, (2) a significant relationship between parents’ SES and consumption-related behaviour, and (3) a significant relationship between parents’ ages and their engagement with children in environmental knowledge and consumption behaviour.

Firstly, the study shows that Chinese parents are actively engaged with their children in all issues regarding EL. Consistently with studies in other educational contexts related to the Chinese parental role [

24,

32,

33], this study revealed that parents in China tend to be pronounced in their agentive role in all aspects of children’ education and life. According to Ahearn (2001, p. 112) [

34], agency is “the sociocultural mediated capacity to act.” Our findings suggest that the way parents act is highly related to their cultural upbringing and beliefs; in particular, their strong feeling of responsibility for their children’s education, conduct, and wellbeing shows this [

35,

36]. The Chinese parenting style is traditionally considered authoritative, but with a strong sense of self-control and a clear understanding of the importance of being role models for the children [

37,

38]. Influenced by Taoism and Confucianism, Chinese parents believe in imperceptible influence through actions. The ideology of governing by modelling is deeply rooted and shows itself in their everyday conduct [

37], also when they socialise their children to become environmentally responsible citizens.

The agentive role of parents is also consistent with studies in other contexts in Europe and New Zealand [

10,

22,

24] where parents act as socialisation agents influencing children’s attitude towards and behaviour regarding the environment. The high level of engagement found in this investigation reflects the implicit efforts that parents make through the process of socialisation. Discussions about an environmental TV programme, reading a story about environmental protection, and talking about nature during an excursion are all part of implicit socialisation, reflecting some “conscious decisions” through “unconsciously” produced family interactions and parental modelling. Unlike the findings from Aguirre-Bielschowsky et al.’s study (2017) in New Zealand, where parents felt less confident when explaining environment-related knowledge, the parents in our study showed strong beliefs in their efficacy when engaging with children’s EL. This again reflects their beliefs in the “capacity to act” as role models, especial with regard to behavioural patterns, such as their ability to explain “why using public transport/walking is better than driving”.

Secondly, there was a significant relationship between parents’ SES and consumption-related behaviours, but the relationship was negative. The same was even more strongly reflected in parents’ level of education, which indicated that the higher the level of parental SES and education, the lower the level of engagement in knowledge acquisition and environmentally friendly consumption behaviour. This relationship is not in line with studies from the UK [

12] and Australia [

39], where parents with higher education were more inclined to talk about and act upon environmental issues. One of the explanations is that Chinese parents with higher SES or education tend to have a relatively busier work schedule and, therefore, less time to engage with their children’s construction of knowledge and understanding of the environment. Another explanation could be that parents with higher SES and higher levels of education are financially better off and, therefore, care less about saving energy by reducing consumption, such as “not buying excessive toys and gadgets” or “not using bottled water”. On the contrary, parents who are well off are often reported to use toys and gadgets as rewards for their children’s academic achievements or other accomplishments. As many families have only one child, the practice of rewarding the child with toys and gadgets may not be considered damaging to the environment [

40]. In addition, most Chinese parents have high academic expectations for their children; if the environmental knowledge/protection is not included in the formal educational curriculum, parents may not prioritise it as an educational goal for their children. In the mundane everyday life, pro-environment practices may be ignored or pushed aside by parents. Most importantly, environmental issues may not be seen as important when related to financial concerns or other pressing issues in everyday life, so engagement in the environment is likely to be at the bottom of the “to do” list.

The third finding from the study showed a close inverse relationship between parents’ age and their engagement in knowledge acquisition and consumption-related behaviour. This finding is, however, not entirely supported by other empirical studies in the literature [

41,

42,

43]. Torgler et al. (2008), for example, found no visible parental age effect in terms of environmental preferences; nor did the studies by Thomas et al. (2018) in the United Kingdom (UK) and Milfont et al. (2020) in New Zealand, which showed that parents’ age has a significant effect on their environmental behaviour. Researchers argue that parenthood may be complicated by stress, income problems, and workload; parents may need to use their resources and energy for more immediate and pressing issues related to childcare responsibilities and their children’s needs, health, and wellbeing. As a result, this may reduce their motivation, capacity, and ability to act in a pro-environmental manner.

While empirical studies may not provide evidence of the effect of parental age on environmentalism, a recent Gallup poll in the US showed different results [

44]. For example, it was reported that “70% of Americans age 18 or 34 worry about global warming. This compares with 62% of those 35 to 54 and 56% who are 55 or older” [

44]. Similarly, our findings indicate that younger parents are more active in their engagement with their children in EL. This is also not surprising, as parents born in the late 1970s and 80s were exposed to a more environment-related curriculum in formal education, so they may be more aware of the impact of various problems on the environment. These younger parents have been exposed to media reports about the environment and climate change most of their lives, so they are more alert to the impact of increased levels of carbon dioxide and other types of pollution. They are more receptive to new approaches to protecting the environment and have formed habits in relation to pro-environmental activities that are different from those of the older generations.

6. Conclusions

Previous researchers have found that parents’ environmental knowledge, attitude, and behaviour can have various degrees of influence on their children [

22,

25]. Our study contributes to the limited literature on parents’ agentive socialisation role in their engagement with children on pro-environmentalism. While our findings indicate the importance of socialisation at home for forming children’s pro-environment acts, more studies are needed to understand how such agency can be a force for social transformation and change. In this respect, building children’s agency is particularly crucial, as they are the future bearers of the impact of today’s environmental problems. Although our study focused on the parental role in the private household sphere, we argue that making social and environmental changes for the better is a concerted effort that requires both schools and families to work closely together.

Educating the next generation needs new curricula that take into consideration the environmental problems that have direct personal relevance in children’s lives. Social change is driven by collective action; only when parents, children, and teachers work together can environmentalism be successful.

Our study has limitations. Firstly, the snowball sampling does not provide a fully representative sample of the population of parents in China. In particular, our sample included a disproportionate number of parents with higher levels of education and higher than average SES. As the data were collected via an online survey, it is difficult to estimate what proportion of individuals who received a link to the survey decided to fill it in, and how this sample compares to those who did not decide to participate in the study. Secondly, it can be seen that the average results are very high, which suggests that there is a ceiling effect in the case of some variables. Changing the response options from agreement to frequency might solve this issue. It might also give us more insight into how frequently parents engage their children in issues related to the environment. Nevertheless, being one of its own kind, this study provides a set of baseline data necessary for future research into parents’ engagement in EL with children in China.