1. Introduction

Efforts to eliminate health inequalities are a matter of global importance [

1]. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, established at the request of the United Nations, proposes global and regional commitments to reduce these inequalities [

2,

3].

It has been revealed that health inequalities exist between the population of African descent of the Americas and other population groups [

4], with scientific evidence of these differences shown in conceptualisation, methodologies, and research tools, and ways of analysing or intervening [

5].

The World Health Organization (WHO), in the document for the World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance, held in 2001, urges the link between racial discrimination and health, noting the need for further research to study the connections between health outcomes and racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, and forms of intolerance [

6]. In addition, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO/WHO) has raised racial discrimination as a social factor in the establishment of health differentials among individuals. Discrimination at the health level operates in different forms: difficulties in accessing services, low quality of available services, lack of adequate information in decision-making, or through indirect mechanisms such as lifestyles, place of residence, type of occupation, income level, or individual status [

7].

Subsequently, PAHO/WHO’s 29th Pan American Health Conference called for the study of presumptive discrimination against minorities with regard to access to health services, highlighting that the population of African descent of the Americas often has more unfavourable health outcomes than the rest of the population [

8]. The region of the Americas thus becomes the first to respond to the need to adopt an intercultural approach in the context of social determinants of health with the adoption of the first policy on ethnicity and health by all its Member States in 2017 [

4].

Prior to this study, a systematic literature review was conducted to identify health inequalities amongst people of African descent in the Americas, which has guided the design and analysis of this work [

5]. The systematic review allowed us to support our claim for the need to work on the concepts of racism and racial discrimination as central categories of analysis with evidence, and provided evidence for our work on the concepts of racial ethnic identity, Afro-descendant culture, traditional medicine, social determinants, racial segregation, community health, intercultural health, availability, accessibility, acceptability, morbidity, and mortality. These variables would be addressed from the differentiated roles of the three groups of interviewee experts on intercultural health, representatives of ministries of health, or Leaders of Afro-descendant organisations. The references provided in this article complement these variables and address, among other things, the health inequalities and social determinants faced by and affecting Afro-descendant populations in the Americas. They also help to show how these inequalities relate to stigmatisation and racial discrimination. In addition, these references highlight some important efforts that are being conducted, both regionally and globally, to eliminate these inequalities, including the approval by all ministries of health of the first policy on ethnicity and health in 2017.

Problems have been identified during data collection regarding people of African descent, as this is not clearly differentiated in the statistics. However, despite this and with the available information, inequities have been found with respect to the rest of the population [

9]. Some of these problems are related to the conceptual differences needed to define the ethnic-racial variable and the underutilization of the variable in data collection, among others. This work proposes a qualitative approach to discriminatory health issues, in particular regarding the population of African descent of the Americas. This qualitative approach is intended to complement the quantitative evidence that exists in relation to this health inequality [

1,

5,

9,

10,

11,

12] by providing a certain level of detail that is typical of the qualitative analytical approach, especially in complex and multi-causal matters, as is the case here.

The objective of this work is the internal thematic exploration of ethnic-racial discrimination towards people of African descent of the Americas regarding their access to health services, abuse during care, and the quality of the received services. In particular, emphasis is placed on the description of public policies, universal access to health and coverage, accessibility of health services, discriminatory behaviours and attitudes towards Afro-descendants while accessing health care, racism, and ethnic inequalities in health.

2. Materials and Methods

Given the complexity of the topic to be explored, a qualitative design was used, which takes elements of grounded theory and supports the analysis with the Atlas.ti v.8.2 software. In the design, the categories and variables assessed through questions to the interviewees were defined. Through their answers, approximations to the relationships between these categories and the different variables were codified for the analysis [

13]. The analysis and results of this work are considered an approximation, which should be further researched from the conclusions extracted.

2.1. Sample

An intentional sampling was carried out, selecting people from different social or institutional areas, in order to identify differentiated knowledge and explanations of ethnic inequalities concerning the health of the population under study. For the choice of informants, the geographical region, country, age, and sex of the person to be interviewed were considered. The final number of interviewees was 20. Of these, 5 were linked to ministries of health and other relevant ministries and government entities in Costa Rica and Peru (including the Ministry of Culture and the Social Security Fund); 1 was linked to the ORAS CONHU (Andean Health Agency, Hipólito Unanue Convention), representing 6 Ministries of Health (Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela); 7 were international leaders from Colombia, Mexico, Panama, and Peru; and 7 were international technicians specialised in intercultural health and African descent populations. The interviews were conducted after signing the informed consent and with the support of a guide with semi-structured questions; some were conducted virtually and others face-to-face. Of the 20 people interviewed, 8 were women and 10 identified themselves as Afro-descendants. The average age of the interviewees was 30 to 50 years old. At the time of the interview, they were located in Peru, Costa Rica, United States, Panama, Mexico, and Colombia.

2.2. Procedure

The interviews were conducted by the lead researcher, trained in qualitative methodology. Appointments adapted to the participants’ agendas were arranged and held in a familiar environment that each of them proposed so as to facilitate communication. The script was designed with the questions (see

Table 1). Each interview lasted approximately 45 min, with a range of between 30 and 60 min. Interviews were recorded, and a code was assigned to each participant to maintain their anonymity. These were subsequently transcribed to facilitate the extraction and analysis of the contents.

2.3. Data Analysis

The texts from the interviews’ transcripts were independently analysed by two researchers. Subsequently, the results were triangulated, resolving the discrepancies through consensus, without requiring the intervention of a third researcher as a mediator. The Atlas.ti v.8.2 software was used for the analysis.

A two-way categorisation and coding process has been applied:

Top-down: Based on the fundamental theoretical models and concepts found in the specialised reference literature, a category structure was established as indicated in

Table 2. Each of the defined categories was linked with its concept or its higher category in the hermeneutic unit, thus establishing a top-down tree under a theoretical foundation logic. We use here “hermeneutical unit” in reference to the set of elements, interrelated among themselves, and with different levels of abstraction and utilities, that make up a qualitative analysis process with Atlas.ti. The idea is based on the Grounded Theory, originally by Glaser and Strauss [

14]. In basic terms, the structure of any qualitative analysis should be supported by pre-existing general theories (that give researchers some references to construct their own analytic and flexible structure, changeable during the analytic process), specific theories (that grow out of data from interview transcription in our case), dimension and categories (middle abstraction ideas), codes (first steps in abstraction), and quotes (or units of context, that give sense to codes). With regard to this article, the main categories considered were socio-racial segregation and racial discrimination, which would be linked to each other in a hermeneutic unit. The theoretical study found the need to include the living conditions category, which refers to social determinants, and these in turn to inequality, race, class, poverty..., as shown in

Table 1. The definition of the codes thus shared a top-down basis from the theoretical dimensions and categories but was completed bottom-up [

15,

16].

Bottom-up: Based on the transcripts, a count was made of the words contained therein, which was prioritised by frequency, from highest to lowest. From this list, words that met the following criteria were selected: (1) maintain a clear semantic relationship with the research objectives, and specifically with the selected categories (socio-racial segregation and racial discrimination); (2) appear in the list of frequencies with a relative weight in the transcriptions greater than 0.025% of the total words posted for the total analysed documents. These two criteria were intended to strengthen the coding system on theoretical and, at the same time, objective-quantitative criteria because, when applied, the selected words nominated the codes used in the automatic coding process. This process was extended, as usual, to the families of the selected words, using the lexeme root in the search. For example, the “racial” code was used when “race”, “races”, or “racial” appeared in the transcribed text. But “world” was not used, despite meeting criterion 2, because it did not meet criterion 1 (semantic relationship with selected categories). As a unit of context for coding (defining what Atlas.ti calls “quotes”), the phrase was adopted, that is, the text space between one point and another. With this in mind, the transcripts were made with special care in respecting the punctuation marks.

In addition, to introduce links between codes into the hermeneutic unit, an objective criterion based on a certain level of co-occurrence was used in the same unit of context. Co-occurrence is defined as the number of times two codes match within the same unit of context. The relativization of this absolute number of events was done by means of the co-occurrence coefficient: “C”, calculated as

where:

n12 = cooccurrence frequency of two codes, c1 and c2,

n1 = frequency of occurrence of code c1,

n2 = frequency of occurrence of code c2.

The calculation of the co-occurrence coefficients was carried out by following the corresponding order to the system. In the rows of the cooccurrence table, all the codes of the hermeneutic unit were established, and, in the columns, the codes were established following the criteria described above, which defined the theoretical system (concepts, categories, dimensions) that underpin this work. This decision also intended to consider the relative presence of the theoretical construct used in this article (segregation–discrimination), independently of the total discourse (multi-conceptual complex) collected in the interviews.

Finally, the linking system (edges) between the elements of the conceptual maps was based, in turn, on two criteria. (1) Theoretical criterion: the category that includes a code is linked to that code, and the codes included in the same category are linked to each other. For example, the “socio-racial segregation” category is linked to the “racial” code and to others included in its theoretical system, which explain the category. All codes included in that category are linked to each other. (2) Objective criterion: Codes of different categories are linked to each other only when they show a co-occurrence coefficient greater than or equal to 0.15. The choice of this cut-off point (0.15) was made on the basis of the simultaneous consideration of the statistical distribution of the co-occurrence frequencies and the symbolic interest of the resulting cognitive network map. This use of mixed foundations (qualitative and quantitative) is increasingly common in analyses using CAQDAS software, regardless of the subject of research [

31,

32].

2.4. Ethical Aspects

At the operational level, and to consider the possible ethical aspects related to data collection and the subsequent analysis, the person was informed, prior to each interview, about both the objectives of the study and the methodology. A written informed consent model was provided to each participant containing the reference person’s name and surname (ultimately responsible), the purpose of the study, the guarantee of privacy and anonymity of the participants, and date and signatures of the researcher and the participant. The data and transcripts of the interviews were saved anonymously, maintaining confidentiality and the anonymity of the participants. The project has the authorisation of the Research Ethics Committee of the Andalusian Health Administration, Spain.

3. Results

Table 3 shows the most cited codes, which offer an overview of the expert discourse on the subject matter at hand. Beyond general matters, which are indicated by the primary positions of the frequency column (care, politics, inequalities, access), reasoning elements were articulated that, despite claiming to be general concepts, relate to specific aspects. Thus, important references to power, skin colour (black as a “class mark”), differences (as the basis of inequality), rights (as ethical-legal bases), or mortality (as a result of inequalities) appear.

Once the concurrency coefficients linked to the theoretical construct “socio-racial segregation + discrimination” is calculated, the highest values are observed in the following codes: “racism” (0.29), “care” (0.18), “racial” (0.12), “access” (0.11), and “black” (0.10). Conversely, the lowest concurrency coefficients are found in “exclusion” (0.01), “mortality” (0.02), “power” (0.04), and “segregation” (0.05) (

Table 2).

Moreover, the basic exploration of the concurrence of the most frequent codes with the “socio-racial segregation and discrimination” theoretical construct offers a double discourse dimension: on the one hand, a more axiological dimension composed of needs, values, and fundamentals (race, racism, care, access to health) and, on the other hand, a more practical dimension (related to the consequences of discrimination) with arguments such as power and authority management for access to health systems (politics, inequalities, segregation) and mortality and exclusion (as more frequently verbalised matters).

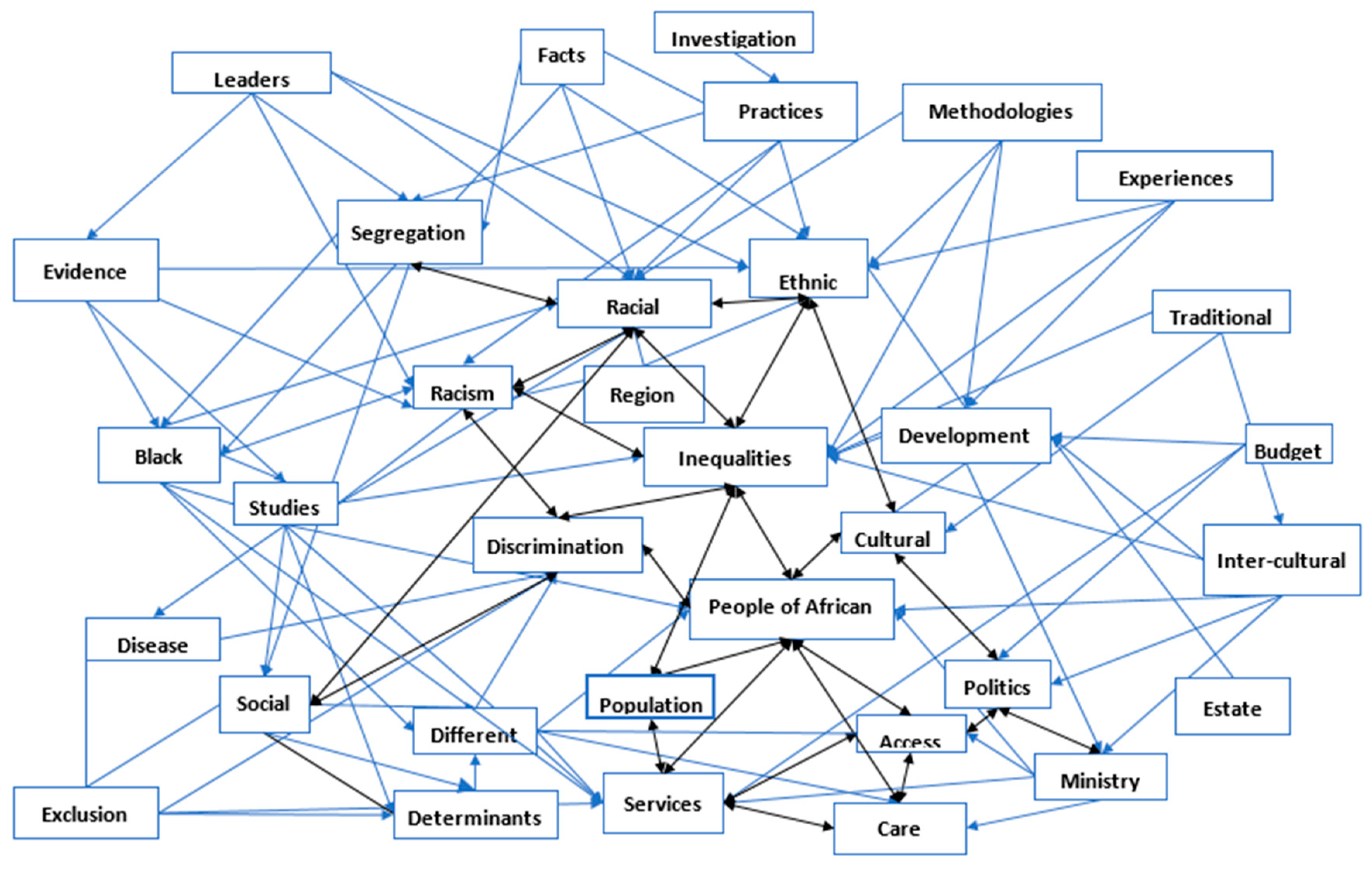

Similarly, from the interviewees’ responses, a global conceptual map was generated that allowed greater content and better understanding of the relationship between the most relevant categories obtained in the results (

Figure 1). The network displayed in the conceptual map in

Figure 1 shows the complexity of relationships where ethnicity, with different levels of concurrence with two-way directionalities (see arrows), interacts with politics, access, services, and care; furthermore, the map gives a great weight to racial discrimination and segregation and inequalities, in this case ethnic inequalities regarding health issues (see arrows in black).

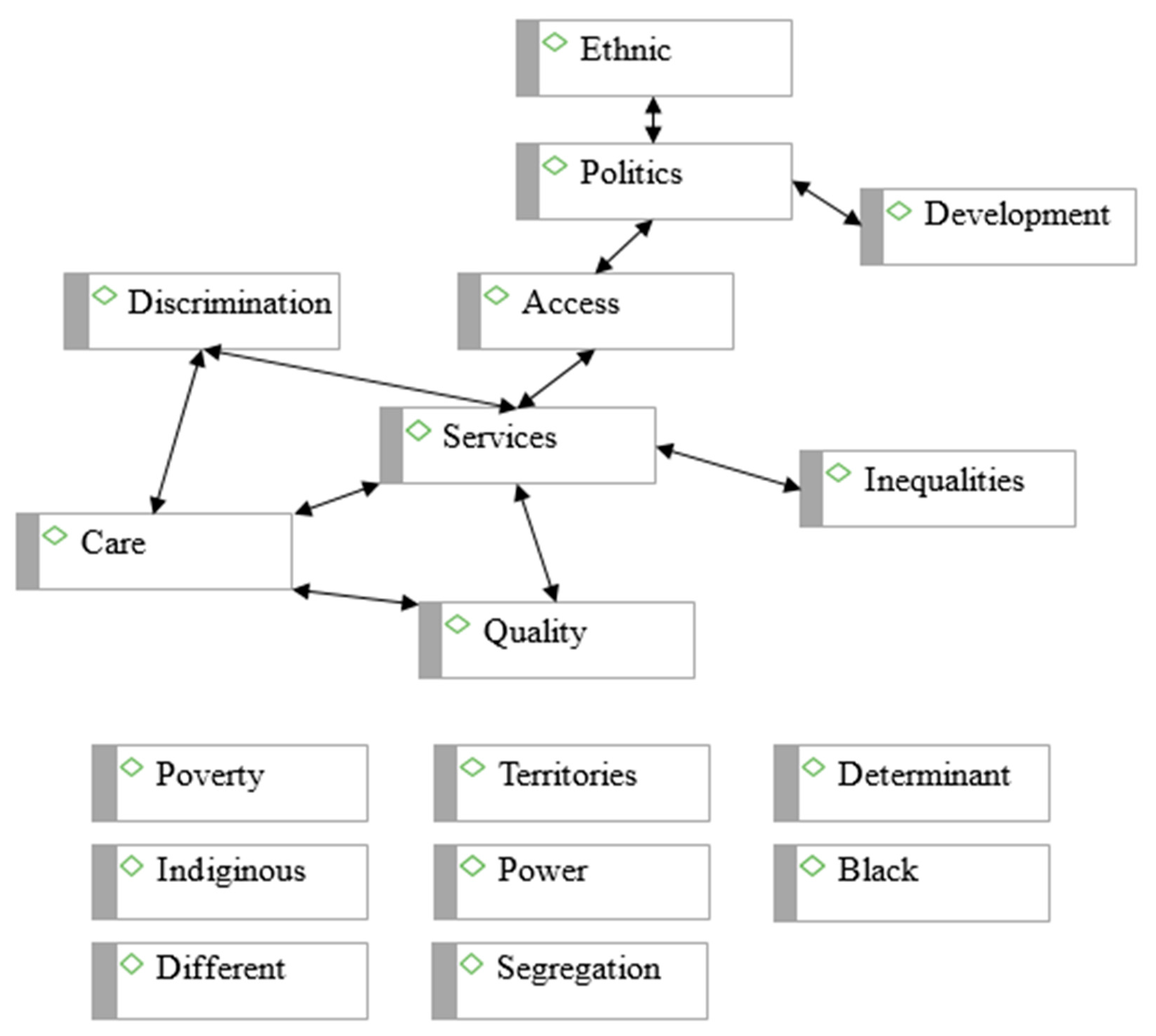

3.1. Racial Discrimination

Figure 2 shows the strength of the relationship, through two-way arrows, of race issues and their connection with discrimination and care (this image reflects data on concurrency coefficients of 0.29), and the latter with the degree of health care (concurrency coefficient of 0.18). In turn, race issues are associated with segregation (concurrency coefficient of 0.04). On the other hand, a relationship between politics and the level of access to healthcare is found.

In the interview analysis, racial discrimination is negatively related to access possibilities and quality of the health services received by people of African descent, both in rural and urban areas:

“This discrimination influences all aspects of treatment experienced by patients of African descent, such as considering their participation in what is health, among other things. Discrimination is very strong in the countries of the region, and the development of specific care protocols and care guides to combat discrimination is currently being considered for the Andean region” (Ministry Official, E2).

“There is strong discrimination in the countries of the Andean region, with the development of specific care protocols and care guides to combat discrimination being considered for the region” (Ministry Official, E2).

Leaders believe that this discrimination is a general problem in all countries of the region and that it has an effect on access to services and quality of care, while technicians, from a more academic and advisory approach, propose:

“... in the region’s health systems and services, in the different countries, there is tacit recognition that there should be no discrimination. However, this standard is not present in notices or protocols. The truth is that health services discriminate, and they do so in a very subtle way or, in other cases, in a very obvious way” (International Technician, E2).

3.2. Ethnic-Racial

The conceptual map allows to observe the relationship between ethnicity, policies, access to services, and quality care, with the side effect of discrimination and inequalities. This map reflects the data obtained in the interviews and is organised according to concurrency coefficients that express the strength of the relationship between the aforementioned variables.

As shown in

Figure 3, the racial ethnic concept makes it possible to identify racism as one of the elements that contributes to health inequalities for the African descent population of the Americas. Ethnicity relates to access to health services through politics, being conditioned by the level of development and influencing their level of care and quality. This difference in health services results in inequality and discrimination among the collective.

Both leaders and officials believe that evidence and vindication to act against the collective’s discrimination regarding their health care has been initiated:

“… since the Santiago de Chile Conference, preparatory to the third World Summit against racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, and related intolerance, where leaders of African descent claimed the African descent concept, … situations of racism and racial, structural, and systemic estimation are highlighted as they affect the population of African descent, as well as how the racial ethnic dimension … has an important connotation in all aspects of the health and economic and social development of people of African descent due to the weight of racism … to evidence how on equal characteristics, the racial ethnic status affects the different social indicators, which are recorded and show the asymmetries associated with the African descent population” (Leader of African descent, E1).

“… we have seen how the population with the lowest level of education is the African descent population; it is the one that has more pregnancies and where maternal mortality rates are higher often because pregnancies are complicated by diseases typical of the African descent population” (Ministry Official, E1).

3.3. Health Policies for the Collective

Policies on access to health services seem to have a significant weight, so the perceived need to promote health policies for the population of African descent may be inferred (

Figure 3).

Technicians indicate that important policy steps have been taken:

“The important step that has been taken in the region with the approval of the PAHO Member States is the first policy on ethnicity and health in 2017” (International Technician, E2).

“… The progress that has been made in the region has been made with the adoption of the Strategy and Action Plan on Ethnicity and Health in 2019, which incorporates the intercultural approach and the impetus, among others, of traditional medicine, the generation of evidence, the promotion of politics within ethnic groups, including the population of African descent” (International Technique, E2).

Similarly, technicians raise the need for an intercultural approach towards the promotion of these policies:

“… the importance of an intercultural approach to foster policies, since although there is wide regulation in the region, it is essential to have support for implementation and follow-up in terms of monitoring and evaluation” (International Technique, E2).

“… the intercultural approach to health issues is key to narrowing these health gaps because it will allow traditional systems to understand that these communities have particularities” (Leader of African descent, E2).

Leaders and technicians share the belief that positive steps have been taken but that there is still a long way to go:

“… there are important opportunities to carry this out, including the 2030 agenda and the International Decade for People of African Descent” (Leader of African descent, E2).

“… Despite some progress, there is a long way to go and greater commitment is needed; more budget should be allocated because the debt to this population is very large” (Ministry Official, E2).

3.4. Access to and Quality of Health Services

In

Figure 3, access to health services, mediated by politics in the ethnicity variable, conditions the quality of the service, this being a reason for inequality and discrimination. Differences based on rural or urban areas have also been observed in interviews.

Leaders have identified differences in access and quality of the service between the rural and urban populations and the influence of these on the African-American population of the Americas.

“… of particular concern is the situation of the population of African descent living in remote areas, where health care is precarious. These communities are also considered to be the most excluded in public policy issues” (Leader of African descent, E2).

Officials and technicians recognise the level of exclusion, vulnerability, and stigmatisation, in part because of a lack of sensitivity towards the collective:

“When analysing the situation of the population of African descent, these people are recognised as excluded, vulnerable, and stigmatised, thus affecting the coverage, access, and quality of the health services provided to them because of stigma, as stating their African descent is a way in which they become isolated from access to the services” (Ministry Official, E1).

“… and this lack of sensitivity in the context is what generates exclusionary practices that do not allow adequate care for people or that cause many doctors or nurses to refuse to go to those areas of African descent populations; well, they say that these are remote areas, where there is no means of communication or infrastructure, and where they are besieged by armed conflict” (International Technician, E1).

Technicians consider it necessary to break down access barriers:

“… the causal relationship is quite clear: if we want to promote access and universal population coverage of quality and comprehensive health services, we need to break down or reduce access barriers. And all official, regional, and national studies coincide in pointing out that one of the most important of these is cultural barriers” (International Technician, E1).

“… hindering people’s access to health services is certainly an issue that requires a lot to work on because it is not only racial discrimination but also social; it is cultural discrimination of which not only the population of African descent is a victim, so are other minorities like transgenders, minorities with different gender identities, women…” (International Technician, E1).

Leaders highlight greater discrimination against women in access to health care:

“… So when those women, many of whom are single mothers, heads of households, go to the clinics alone, with no one to support them, with no one to protect them, they still receive discrimination and abuse from doctors and many people who work in those health centres” (Leader of African descent, E2).

“The wide number of women these midwives receive, including prenatal and postnatal care with babies and other traditional forms that are used, have come to contribute, to a greater or lesser extent, to gaps in health care on the part of the authorities regarding the care that should be provided by the authorities” (Leader of African descent, E2).

Technicians suggest that traditional medicine could contribute to greater access to health care for the collective:

“… Although there are no studies, it has been observed that working with traditional medicine would allow us to contribute to universal access to health care for these populations. So, it would definitely be a key factor in guaranteeing these populations access to health services” (International Technician, E2).

“… Some research has been mainly developed in rural communities that have been working on the need to recover the medicinal knowledge that communities of African descent have; the research is mainly on traditional midwifery and on the use of plants to meet the health needs that most affect these populations” (International Technician, E1).

Leaders also believe that traditional medicine and plant use could decrease barriers and strengthen conventional medicine:

“… initiatives could be created to reduce the existing gaps and where traditional medicine of the population of African descent is valued; a dialogue with conventional medicine could be generated to improve the health conditions of the people of African descent” (Leader of African descent, E1).

“… I do believe that traditional medicine, body care, and plant use can strengthen Western forms of health, and that we will be able to see, from there, the common points which can be used in African descent and non-African descent people” (Leader of African descent, E2).

Community leaders of African descent claim their role in improving the coordination of their actions with traditional medicine:

“… Leaders of African descent can mediate between state health care practices and many more community forms, bringing closer these demands from community to state … in order to incorporate elements into health systems that overcome discrimination and contribute to reducing health gaps” (Leader of African descent, E1).

Officials also believe that government agencies are playing an important role in solving the problem:

“… I do think we are now having new proposals as a State with the Health Network System” (Ministry Official, E2).

“Some actions have been done within these areas, but what is needed is the sustainability of the work to be carried out” (Ministry Official, E1).

Technicians highlight the need to evaluate and monitor the quality of the health care offered to African descent groups:

“These models of evaluation and monitoring respond to the differentiated needs of the population of African descent. I think it is an interesting topic to investigate because my impression is that these models of monitoring and quality of care assessment are not adequately gathering the differentiated needs of the populations of African descent and other ethnic groups. I am referring to models of assessment and monitoring of the quality of care applied at the macro level, at the national level driven by large banks, by multilateral agencies, by the academy... These needs are not being collected” (International Technician, E1).

3.5. Negative Outcomes, Diseases, Mortality, Seen as Health Inequalities

Leaders see a higher level of morbidity, with a higher proportion of homicides, while higher maternal mortality is only evidenced in the US (there not being data from other countries):

“… homicide is the leading cause of death among young people in Brazil, and it disproportionately affects young people of African descent; 80% affect people of African descent” (Leader of African descent, E2).

“… there is no inference of data that allows saying, except in the US, that maternal mortality occurs especially among black populations. As statistics in these countries are in the process of improvement so as to include ethnicity…” (International Technician, E1).

Leaders observe how specific or differentiated diseases such as sickle cell anaemia or skin cancer are often unknown in these countries:

“… I am saying this with much sorrow: diseases related to the population of African descent—I’m specifically talking about sickle cell anaemias and others—are not known in our countries” (Leader of African descent, E2).

“… diagnosis of health-related disparities such as skin cancer and other problems for which artificial intelligence is now far from a solution may involve some discriminating factors against people of African descent” (Leader of African descent, E2).

Technicians confirm these inequalities:

“… there are studies that reveal the existence of inequalities in health outcomes, i.e., morbidity and mortality, but sadly no mechanisms have been specifically worked on to reduce this ethnic social exclusion and racial segregation” (International Technician, E1).

“… the epidemiological profile of the African descent population that is related to chronic diseases since adolescence, such as hypertension, overweight, etc., is striking, and it suggests a very subtle discriminatory burden on health services regarding access, which is equal to indigenous populations” (International Technician, E1).

4. Discussion

This study has facilitated analysing the different aspects linked to discrimination regarding access to and quality of health care for the people of African descent of the Americas, as well as discriminatory behaviours and attitudes towards Afro-descendants while accessing healthcare. An approach is made to possible causes and solutions through the contribution of a group of key informants made up of social, institutional, and academic actors with experience in the field.

The data in this study are consistent with the benchmarks for clarifying the meaning of racial discrimination and segregation proposed by WHO [

6] and the joint position adopted by PAHO [

7]. The contributions of leaders of African descent, interviewed according to their different roles, stated that discrimination is present in all countries of the region with effects on access to services and on the quality of healthcare.

The need to clarify the racial ethnic concept was identified in at least two ways: on the one hand, for the verification of racist actions that occur in health services and, on the other hand, for use in data collection systems. In this regard, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) states that notions of “race” and “ethnicity” have not only served as a conceptual platform for mobilising the political identity processes of people of African descent but that notions of “race” and “ethnicity” have allowed the foundation for self-identification of these populations in censuses and surveys. An improvement in data is indeed observed, but weaknesses and limitations are also still perceived, generating statistical invisibility [

33].

Public policies should evaluate and respond to the links between negative health outcomes and racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, and related intolerance. In this regard, the National Policy of Integral Health Care of the black population set up by the Ministry of Health of the State of Sao Paulo between 2003 and 2010 is a reference. After analysing the strategies and mistakes made, racism was included on the political agenda as a social determinant of health. This facilitated professional and civil society awareness, the inclusion of race/skin colour in information systems, and consciousness of the need to invest in assessment indicators and renewal of the learning processes for policy feedback [

10]. However, the present study revealed that the same is not true in most surrounding countries that do not include specific mechanisms to ensure access to the health services.

Our results confirm the PAHO proposal’s recognition of the need for political commitment and a consensus strategic framework to move towards health equity by developing the first policy on ethnicity and health for the Americas; it was unanimously approved by all ministries of health in September 2017 during the 29th Pan American Health Conference. The Report called for exploring the weight of the assumed segregation and discrimination against minorities [

8].

Studies in the United States have shown that doctors and health workers do not take medical complaints from people of African descent seriously, and that medical mistrust can be a consequence of segregation [

34]. In addition, African Americans/black people are less likely to find an unrelated donor [

35]. All of this led to the statement that improving quality and reducing racial and ethnic health care disparities are two important and related health care challenges in the United States [

36,

37,

38].

The present study highlighted the geographical variable, because of the worrying situation of the population of African descent living in remote areas, where health care is more precarious. These results coincide with a study conducted in Mexico, where a geographical pattern of distribution of the marginalisation index and the Afro-Mexican population was established, and which is far from random [

39]. In Colombia, the geographical variable has been found to be a source of residential segregation, which appears as discrimination with respect to the use of reproductive health services [

22].

The interviews carried out in the present study highlight the situation of single mothers who attend clinics alone and receive discrimination and abuse from doctors and other health centre workers. A possible solution would be to value the traditional medicine of the people of African descent, generating a dialogue with conventional medicine. Rescuing traditional medicine, body care, and plant use may strengthen Western ways of health care, both for people of African descent and for the rest of the population. The literature refers to experiences in which the intercultural dialogue is a strategy that allows complementing traditional medicine. Such is the case of working in child maternal health in Afro-Colombian communities [

11].

Coordinated work with community leaders at the local level can be a step forward in overcoming discrimination and reducing health gaps. Leaders of African descent often act as mediators between state health care practices and community processes, making it easier to bring the demands of the community closer to the state. An example is the Special Plan for the Safeguarding of Knowledge Associated with Midwifery of the Afro-Pacific Communities in Colombia. However, midwives claim that they often refer pregnant or sick women to doctors who respond by rebuking these women for having turned to midwives [

40].

The use of the word “black” and its connotations may vary by region. Hoffman states that “black” does not belong to the Mexican collective national imaginary and that it only represents decontextualised stereotypes or alienating images, which identify the person as a foreigner. In certain regions of the country, these connotations and associated implications vary depending on the history of those black populations and the elite positions of the collective [

12]. In the present study, this issue was placed in the fifth level of concurrence as regards racial discrimination.

As for racial discrimination related to the use of ethnic-racial categories in censuses and surveys, the initiative of the Peruvian Statistical Institute must be cited here as it is aimed at improving the measurement of the ethnic dimension in official statistics. The National Household Survey (ENAHO) included a variable of ethnic/racial self-identification, while in two rounds of the Demographic and Family Health Survey (ENDES), a module was added with indicators on ethnic markers (such as clothing and link to the community of origin) [

41]. The emergence of the ethnic dimension in the surveys facilitates the investigation of this variable, and this has shown statistical inequality in both morbidity and mortality data; in Brazil, black people have more than twice the risk of death by homicide as white people [

22,

42].

Among the limitations of the study, the number of interviewees may be mentioned, taking into account the variety, among Latin American countries, of approaches to addressing the health of African descent populations in different ways. Future studies could complement and deepen current results with the vision of other subject matter experts.

Finally, the study may allow ministries of health to consider incorporating the training of professional competencies in intercultural health into their plans for healthcare human resources, as well as the use of tools to change racist and discriminatory behaviours and attitudes, which have consequences on the health of the Afro-descendant population.

5. Conclusions

In the present study, racial discrimination and its relationship to accessibility of health services and abuse during care have been studied in the populations of African descent of the Americas, both in urban and rural areas. In relation to racial ethnicity, two dimensions are made evident: one is the politically demanding nature of racial discrimination and the ways African descent organisations deal with this, and the other is that changes must be implemented by institutions in order to have disaggregated information on the population of African descent by including them as a variable in surveys, censuses, and continuous records. Ministries of health perceive the need for more research and training to make appropriate and useful decisions that affect these populations. It is important to emphasise the need for differentiated approaches that consider the ethnic-racial needs of people of African descent. And to do so, intercultural approaches are a fundamental tool.

With regard to public health and ethnicity policies, the lack of budget for implementation and, as the evidence indicates, the lack of monitoring, evaluation, and accountability are identified as the main problem.

Based on racial discrimination, structural and functional discrimination are observed. Thus, the latter entails barriers to access to health services and deficiencies in the quality of care, which has negative effects that are expressed through ethnic inequalities in the face of disease and death. Such racial discrimination, when associated with spatial racial segregation, social class, sex inequalities, and other conditions may lead to its maximum expression of intolerance and discrimination in the health services context.

The manifestations of racial discrimination in the health care context are related to the availability of these services in urban and rural areas where people of African descent live, to the prioritisation of delivering services of medium and high complexity, to the undervaluation when organising and providing services, to stigmatisation against certain types of health issues, and to the quality of services to the detriment of the expected results.

A pending issue for countries is to improve health information management, in this case, generating the necessary input on racial discrimination through systems that ensure the quality of the health care services so as to design monitoring, evaluation, accountability, and improvement plans.

With the evidence and the approaches obtained from the interviewees as a benchmark, knowledge has been widened on understanding how racial discrimination is one of the main mechanisms that generate ethnic inequalities in health matters by hindering access to and quality of the health services provided to people of African descent in the Americas.