The Practice of Co-Production through Biocultural Design: A Case Study among the Bribri People of Costa Rica and Panama

Abstract

:1. Introduction

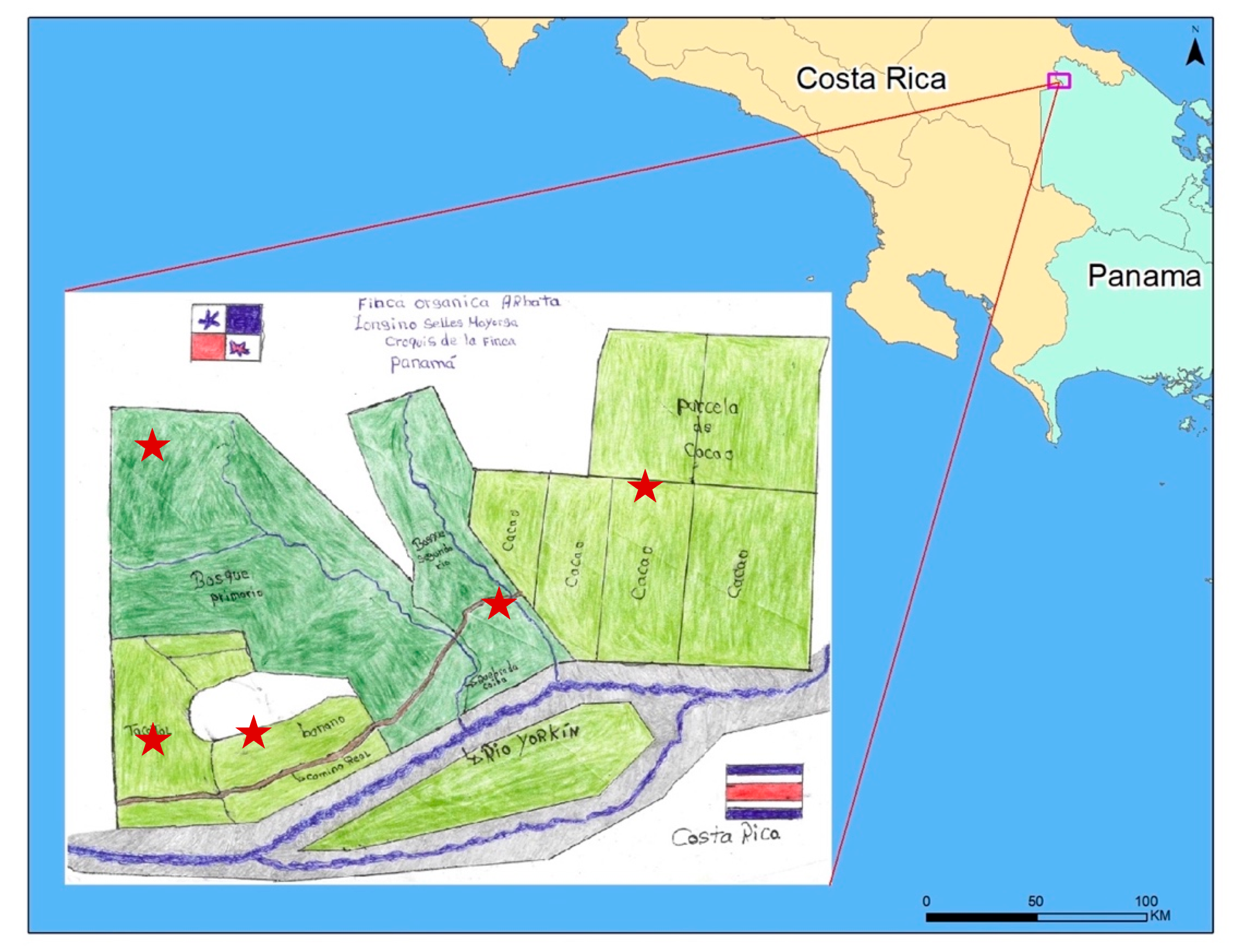

2. Research Methodology

- The majority of people I talked were not interested in designing cacao products and services (N = 14).

- Some community members were not part of this project because they were busy with other activities (e.g., working on their banana/plantain farms) (N = 8).

- A couple of people expected me to teach them “something new” (N = 2).

- Other community members were interested in different types of projects (e.g., people wanted to be part of projects unrelated to the production of cacao) (N = 4).

3. Results

3.1. Inspiration Phase

3.2. Ideation Phase

3.3. Implementation Phase

3.3.1. Developing and Implementing Products with the Morales Family

3.3.2. Developing and Implementing Products with the Celles Family

4. Discussion

- Access and availability of materials (e.g., diversity of Theobroma and other plant species)

- Specialized place-based knowledge (e.g., location and use of biological resources, Bribri cultural narratives)

- Placed-based practices (e.g., techniques to transform plants into dishes and medicines)

- Strategic alliances with key actors to gain access sources knowledge (e.g., neighbors, researchers, Bribri traditional authorities) and access to markets (e.g., touristic operation)

- Strong attachment to biological resources tied to the Bribri identity (e.g., cacao)

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miller, C.A.; Wyborn, C. Co-production in global sustainability: Histories and theories. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.01.016 (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Lemos, M.C.; Kirchhoff, C.J.; Ramprasad, V. Narrowing the climate information usability gap. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hel, S.V.D. New science for global sustainability? The institutionalisation of knowledge co-production in Future Earth. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 61, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schuttenberg, H.Z.; Guth, H.K. Seeking our shared wisdom: A framework for understanding knowledge coproduction and coproductive capacities. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schneider, F.; Giger, M.; Harari, N.; Moser, S.; Oberlack, I.P.; Schmid, L.; Tribaldos, T.; Zimmermann, A. Transdisciplinary co-production of knowledge and sustainability transformations: Three generic mechanisms of impact generation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 102, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Environmental Governance for the Anthropocene? Social-Ecological Systems, Resilience, and Collaborative Learning. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Armitage, D. Social-ecological change in Canada’s Arctic: Coping, adapting, and learning for an uncertain future. In Climate Change and the Coast: Building Resilient Communities; Glavovic, B., Kelly, M., Kay, R., Travers, A., Eds.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Meadow, M.A.; Ferguson, B.D.; Guido, Z.; Horangic, A.; Owen, G. Moving toward the Deliberate Coproduction of Climate Science Knowledge. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2015, 7, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davidson-Hunt, I.J.; Turner, K.L.; Mead, A.T.P.; Cabrera-Lopez, J.; Bolton, R.; Idobro, C.J.; Miretski, I.; Morrison, A.; Robson, J.P. Biocultural Design: A New Conceptual Framework for Sustainable Development in Rural Indigenous and Local Communities. Surv. Perspect. Integr. Environ. Soc. 2012, 5, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Swiderska, K. Protecting Traditional Knowledge: A framework based on Customary Laws and Bio-Cultural HeritagE, Sustainable Agriculture, Biodiversity and Livelihoods Programme. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Endogenous Development and Bio-Cultural Diversity, Geneva, Switzerland, 3–5 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Posas, P.J. Shocks and Bribri Agriculture Past and Present. J. Ecol. Anthropol. 2013, 16, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Serrano, C.R.; Del Monte, J.P. The Use of Tropical Forest (Agroecosystems and Wild Plant Harvesting) as a Source of Food in the Bribri and Cabecar Cultures in the Caribbean Coast of Costa Rica. Econ. Bot. 2004, 58, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, R.; Deheuvels, O.; Calvache, D.; Niehaus, L.; Saenz, Y.; Kent, J.; Vilchez, S.; Vilota, A.; Martínez, C.; Somarriba, E. Contribution of cocoa agroforestry systems to family income and domestic consumption: Looking toward intensification. Agrofor. Syst. 2014, 88, 957–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.; Davidson-Hunt, I.J. Resilience and the Dynamic Use of Biodiversity in a Bribri Community of Costa Rica. Hum. Ecol. Interdiscip. J. 2018, 46, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.A.; Gonzalez, J.; Somarriba, E. Dung Beetle and Terrestrial Mammal Diversity in Forests, Indigenous Agroforestry Systems and Plantain Monocultures in Talamanca, Costa Rica. Biodivers. Conserv. 2006, 15, 555–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deheuvels, O.; Avelino, J.; Somarriba, E.; Malezieux, E. Vegetation structure and productivity in cocoa-based agroforestry systems in Talamanca, Costa Rica. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 149, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, M.R.; Davidson-Hunt, I.J.; Berkes, F. Social-ecological memory and responses to biodiversity change in a Bribri Community of Costa Rica. Ambio 2019, 48, 1470–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlquist, R.M.; Whelan, M.P.; Winowiecki, L.; Polidoro, B.; Candela, S.; Harvey, C.A.; Wulfhorst, J.D.; McDaniel, P.A.; Bosque-Pérez, N.A. Incorporating Livelihoods in Biodiversity Conservation: A case Study of Cacao Agroforestry Systems in Talamanca, Costa Rica. Biodivers. Conserv. 2007, 16, 2311–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzivanova, V.; Davidson-Hunt, I.J. Biocultural Design: Harvesting Manomin with Wabaseemoong Independent Nations. Ethnobiol. Lett. 2017, 8, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterlaken, I. Design for Development: A Capability Approach. Des. Issues 2009, 25, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costa Rican Census. Características Sociales. Población Total en Territorio Indígena, Auto Identificación Étnica, Lengua Indígena, Pueblo, Territorio Indígena. 2011. Available online: https://www.inec.cr/sites/default/files/documentos/inec_institucional/estadisticas/resultados/repoblaccenso2011-12.pdf.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- UN. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, General Assembly Resolution 61/295, 107th Plenary Meeting, UN Doc. A/RES/61295. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html (accessed on 21 August 2020).

- Brown, T. Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Deheuvels, O.; Rousseau, G.X.; Quiroga, G.S.; Franco, M.D.; Cerda, R.; Mendoza, S.J.V.; Somarriba, E. Biodiversity is affected by changes in management intensity of cocoa-based agroforests. AgroFor. Syst. 2014, 88, 1081–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzoli, M.E. Narraciones Bribris. Vínculos 1977, 2, 186. [Google Scholar]

- Jara, C.V.; Segura, A.G. Diccionario de Mitología Bribri; Editioral Universidad de Costa Rica: San Jose, Costa Rica, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alford, J. The Multiple Facets of Co-Production: Building on the work of Elinor Ostrom. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| Desirable Ideas a | Feasible Ideas b and Challenges to Overcome | Strategies Used to Solve the Challenges | Viable Ideas c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trail mix made with seeds of the trees located in cacao agroforestry systems | This idea was not feasible because the availability of seeds was seasonal, and we did not have access to the necessary infrastructure to store the seeds for long periods. | ||

| Chocolate bars | This idea was not feasible because we did not have the knowledge and infrastructure (e.g., thermometers, refrigerator, tempering machines) to transform the cacao mass into chocolate bars. | ||

| Fried plantains | This idea was feasible. However, we did not work on it as we were focused on the elaboration of other products. | ||

| Chocolate beverages with the seeds of different Theobroma species | This idea was feasible because we have access to the seeds of the trees and the participants had the knowledge to elaborate the beverages. However, we could not further develop the products because we did not have access to enough seeds. | We grew the seeds in a nursery. Then, we made a plan to transfer the plants in different landscape patches to mitigate the impact of fungal diseases in the trees. | This idea has to potential of being viable. However, it requires more time to become part of a business model. |

| Showcase farm intercropping cacao/banana in the same area | The idea was feasible. However, we changed our original design after learning about the white cacao and the cacao Bribri cultural narrative. For the development of this idea, we faced the following challenges: (1) It took us a long time to find the seeds of the trees we needed. (2) Once we got the seeds, we needed to figure out the best way to grow them to avoid the incidence of the monilia. | The participants consulted neighbors and relatives to get the location of the trees. I contacted other researchers to learn the scientific and Bribri names of the trees. | The idea has the potential of being viable. However, it requires more time and reflection to become part of a business model. |

| Cacao jam | The idea of creating cacao jam was feasible. However, we faced the following challenges: (1) The fermentation process was interrupted, and the participants could not sell the seeds to the local cooperative. (2) The participants could not remember how to extract the butter (3) We did not have containers to package the product. (4) We did not know how to sell this product to the tourists visiting the community. | (1) We used the fermented seeds to develop a second product: cacao butter. (2) The participants consulted neighbors for the traditional method to extract cacao butter. (3) The participants and I bought glass containers to package the product. (4) We shared the ideas of the project with some community visitors, and they demanded the product. The participants shared our products with other community members, and they traded for other products (e.g., wood, sugar, rice) | This idea was viable because the participants: - Had access to the cacao seeds and to the knowledge to prepare cacao jam. - Had access to other sources of knowledge, which allowed them to remember how to extract cacao butter. - Had the freedom to select the containers and final design for their product - Decided the price of the product and agreed on how to trade the product for other merchandises with neighbors |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez Valencia, M. The Practice of Co-Production through Biocultural Design: A Case Study among the Bribri People of Costa Rica and Panama. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7120. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177120

Rodríguez Valencia M. The Practice of Co-Production through Biocultural Design: A Case Study among the Bribri People of Costa Rica and Panama. Sustainability. 2020; 12(17):7120. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177120

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez Valencia, Mariana. 2020. "The Practice of Co-Production through Biocultural Design: A Case Study among the Bribri People of Costa Rica and Panama" Sustainability 12, no. 17: 7120. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177120

APA StyleRodríguez Valencia, M. (2020). The Practice of Co-Production through Biocultural Design: A Case Study among the Bribri People of Costa Rica and Panama. Sustainability, 12(17), 7120. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177120