Rapid Games Designing; Constructing a Dynamic Metaphor to Explore Complex Systems and Abstract Concepts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What value does RGD provide to workshop participants and organizers?

- How does RGD work and function to provide this value?

- How does RGD compare to similar methods, and for which applications is it particularly valuable?

2. Literature Review

2.1. What Knowledge-Building Field Does RGD Fit within?

2.2. Where Does RGD Fit in the Literature?

2.3. How New Is “Rapid Games Designing”?

- The search terms used (in various combinations) were as follows:

- [design/making/self-designed/self-made/co-design*/student-designed/student-made/participant-designed/participant-made]

- [games/board games/card games/serious games]

- [serious play/creative visualization/prototype*/lego]

- [facilitation/creative facilitation/workshop/social learning/scenario*/participation/engagement/communication/participatory development communication]

3. Results

3.1. Assessing the RGD Workshops

3.1.1. Reflections on Workshop Efficacy by Facilitators

3.1.2. Reflections on Workshop Efficacy by Participants

- Game design yielded significant insights into assumptions, perceptions and resulting designs of games to reflect real-world or idealistic-world scenarios.

- Stimulation of thought processes and looking at situations from a multifaceted point of view.

- The effectiveness of games to get to the bottom of people’s mindset.

- The idea of playing a game to get people thinking together towards common goals.

- First for me with the interactive creative games. Very powerful tool. Would like to learn more.

- The approach of the games stimulates thinking. I liked the tools/approach.

- Interesting way of learning (games).

- Using games to illustrate “real-world” issues that educate people.

- Very interesting to use games as a way of thinking and training.

3.2. Assessing the Games Designed

3.2.1. Content: Real World Elements Expressed in the Games

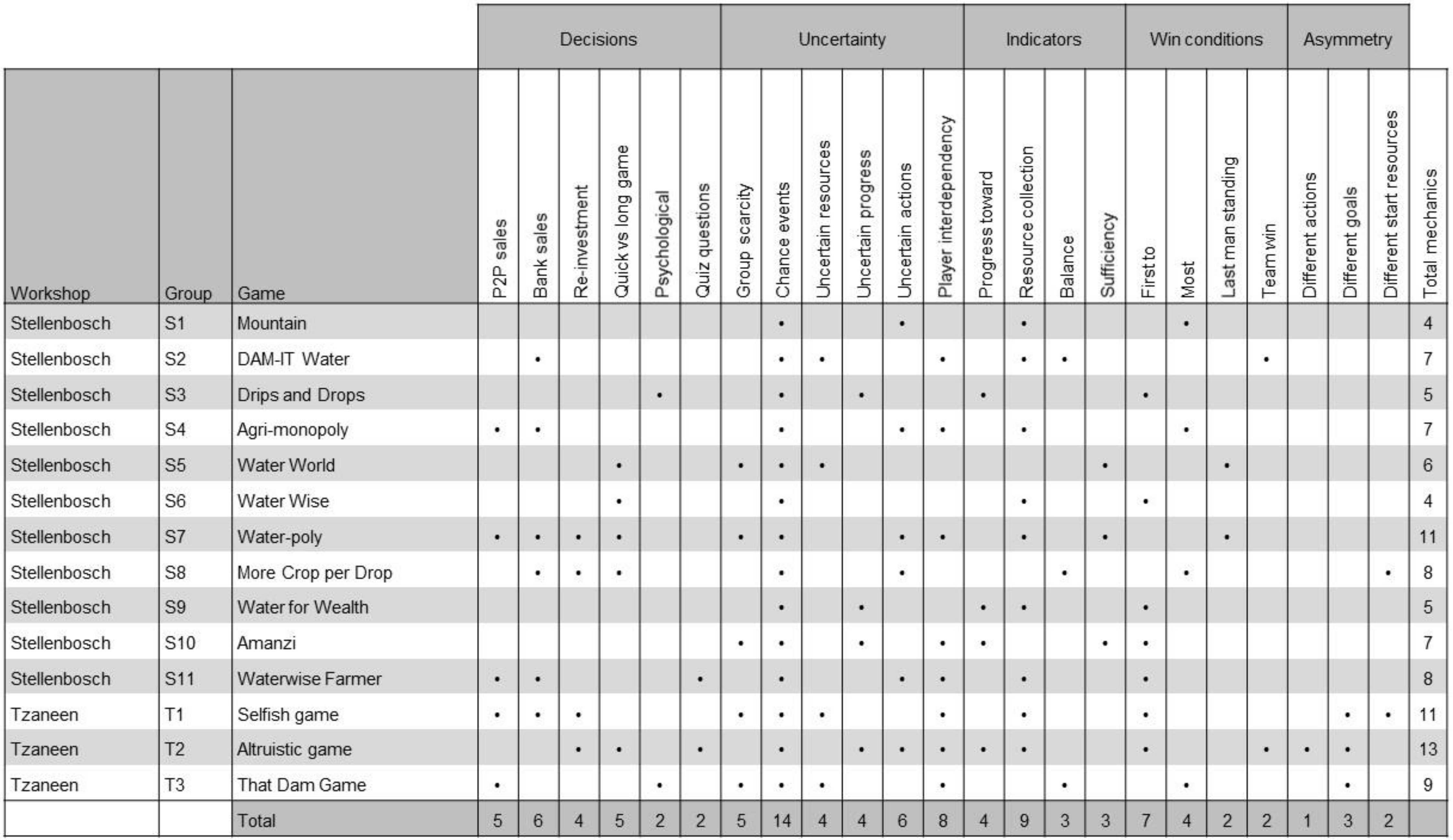

3.2.2. Game Mechanics Used to Express Real-World Dynamics in the Games

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion Question 1: Value of RGD for Workshop Participants and Organizers

4.1.1. Exposing Tacit System Maps: Boundaries, Internal and External Components and Risks

4.1.2. Winning: Perspectives on Success

4.1.3. Human Dimensions

4.1.4. To What Extent Can We Connect the Game World with the Real World?

4.1.5. Additional Benefits: Building Trust and a Shared Vision

4.2. Discussion Question 2: “Under the Hood”—How Does RGD Work and Function?

4.2.1. Rapid Trust Pedagogy

4.2.2. Playfully Designing Games

4.2.3. Expressing the Complex System as a Game Metaphor

4.2.4. Interrogating the Game World Iteratively as a Group

4.3. Discussion Question 3: Contextualizing and Comparing RGD

4.3.1. Comparison with Other Methods

4.3.2. Where Is RGD Particularly Useful?

4.3.3. Future Work to Compare Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Delivering a ‘Rapid Games Designing’ Workshop

Appendix A.1. Introduction, Background and Logistics

- Although the workshop assumes one day is available, the schedule here runs for about five hours with a lunch break in the middle.

- We do not cover the arrangements for setting up and hosting the workshop—e.g., details about email correspondence etc. are not included.

- We use the word ‘dice’ for singular and plural.

Appendix A.1.1. Pre-Workshop Preparation

Appendix A.1.2. Room Arrangements, Group and Table Numbers

Appendix A.1.3. Overall Scheduling of the Workshop

| Welcome and introductions | 10–12 min |

| Stage 1. Introductory technical presentations | 10–12 min |

| Presentation—“why games?” | 10–12 min |

| Presentation—“what to be gamed?” | 10–12 min |

| Presentation—“how to design a game?” | 45–50 min |

| Stage 2. Games designing exercise | 60–80 min |

| Lunch or break | 30–60 min |

| Stage 3. Presentations of games | 40–60 min |

| Stage 4. Plenary discussion | 60–90 min |

| Total: 4.5–6.5 h | |

| Stage 5. Post-workshop discussion and analysis by facilitators/organizers | |

Appendix A.1.4. Support by the Facilitators

Appendix A.1.5. The Games Materials Used

Appendix A.2. Stage 1: Introduction to Games Designing

Appendix A.2.1. Introductory Technical Presentations (10–12 min)

Appendix A.2.2. Presentation—‘Why Games?’ (10–12 min)

Appendix A.2.3. Presentation—‘What to Be Gamed?’ (10–12 min)

Appendix A.2.4. Presentation—‘How to Design a Game?’ (45–50 min)

- What do we mean by winning? What is the win objective?

- Defined by total win or relative win? First to arrive?

- By forms of accumulation? (Of money, marbles, score, a step forward on the game)

- Enabled by speed, strength, position, luck, information, turn, role, bluster, acting and mimicry

- To win, are negotiations mediated by (a) the players, (b) the game physicality & interfaces (c) the game stages, roles and rules, and (d) the game mediator/observer?

- What are the consequences of not winning?

- Intermediate sequences and stages or trade-off positions?

- Start the baby steps by asking someone in the group to select a games world counter or token and to place it in front of their group and then explain the role or actor this token or counter might represent in the real-world (e.g., “this blue counter represents a water law judge or ‘hydropower’”). After a few minutes the tables can shout out some roles they have imagined.

- In the second ‘baby step’, using a photograph of a relevant theme (e.g., a dry landscape or some cattle around a borehole) as a prompt, ask participants to complete the sentence: ‘Interpreting actions as players winning in the real-world and thinking about the resource system (e.g., WASH in a rural or urban community or growing a crop in the Sahel) express to your group ‘how you/he/she/it ‘succeeded/won’ in the real-world when…’. Then we provided an example such as “I won during a drought because I had access to freshwater from a borehole.” (Participants are given 2–3 min working in their table groups to give another real-world example of how they ‘won’ or succeeded).

- Ask the groups ‘Select a dice from in front of you’. (Remember the dice is in the game-world). Then ask them to decide ‘what does the dice represent in real-world terms?’ (For example, the dice represents the rainfall pattern for the year). Now decide what the real-world outcome of rolling the dice is. (Remember the number on the dice is in the game-world). E.g., the number ‘six’ represents a flood. If a table does not already suggest it, you could add a second dice to represent another feature and therefore the impact of the outcome of the first dice. For example, one dice represents rainfall pattern and a second dice represents population density.

- State or instruct: ‘Select a blank card and write on it two related events’: a real-world event and game-world event. An example is ‘a drought’ and ‘deduct 10 points or lose 50% of your money’.

- State: “A pile of counters on the table represents water in a shallow aquifer; taking only two minutes design a simple game to share this water to different players around your table.” (An example might be that each person throws a dice and the person who throws the highest score has total control in deciding who gets the counters).

- State: “Draw any diagram/squiggle/sketch on a poster paper”. (An example is given by the facilitator). Allow the groups to create a diagram, then state again “Now explain how this might be the basis for a game.” For example a large ‘S-shaped line’ becomes a path for players to move along from start to finish similar to ‘snakes and ladders’.

Appendix A.3. Stage 2: The Games Designing Exercise (60–80 min)

- What is the game-world about? What ‘real-world’ is it rendering?

- What is the aim/purpose of your game?

- What are the materials & what do they do?

- Who are the players? Do they have roles?

- What can the players do/how move? (Rules to move next stages/rounds)

- What happens then to the players at the stage/round (stage obstacles and or stage successes)?

- How do they win the game overall?

Appendix A.4. Stage 3: Presentations about the Games by Each Table (40–60 min)

Appendix A.5. Stage 4: Plenary Discussion by Workshop Participants (60–90 min)

Appendix A.6. Stage 5: Post-Workshop

Appendix A.6.1. Analysis of the Games Designed

- “ARDI” analysis: listing Actors, Resources, Decisions and Indicators

- Win conditions

- Role of randomness

Appendix A.6.2. Workshop Analysis by Facilitators/Organizers

- Did the game workshop meet the original objectives of the organizers? How was this tested objectively?

- Did participants arrive at new understandings and/or provide new definitions of the subject matter that was ‘rapidly game designed’? How was this verified?

- What immediate follow-up is required to sustain learning outcomes and actions?

- What improvements might be made in the future to the format and facilitation of a workshop where RGD is employed?

Appendix A.7. Two Reflections on the Workshop Logistics

Appendix A.7.1. Group Size

Appendix A.7.2. Materials and Prompts

Appendix A.8. Photos of Designed Games from Recent Workshops

References

- Harteveld, C. Triadic Game Design: Balancing Reality, Meaning and Play; Springer: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aubert, H.A.; Bauer, R.; Lienert, J. A Review of Water-Related Serious Games to Specify Use in Environmental Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. Environ. Model. Softw. 2018, 105, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maren, W.; Stoll-Kleemann, S. Role-Playing Games in Natural Resource Management and Research: Lessons Learned from Theory and Practice. Geogr. J. 2018, 184, 298–309. [Google Scholar]

- Rieber, L.P.; Smith, L.; Noah, D. The Value of Serious Play. Educ. Technol. 1998, 38, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, W. Serious Play in Education for Social Justice—A Mixed-Methods Evaluation. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 2018, 7, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organisation; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kriz, W.C. Creating Effective Learning Environments and Learning Organizations through Gaming Simulation Design. Simul. Gaming 2004, 34, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, H. From Metaphor to Practice: Operationalizing the Analysis of Resilience Using System Dynamics Modelling. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2017, 34, 444–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alison, J.; Brookfield, S. The Serious Use of Play and Metaphor: Legos and Labyrinths. Int. J. Adult Vocat. Educ. Technol. 2013, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kafai, Y.B. Playing and Making Games for Learning. Games Cult. 2006, 1, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aubert, A.H.; Medema, W.; Wals, A.E.J. Towards a Framework for Designing and Assessing Game-Based Approaches for Sustainable Water Governance. Water 2019, 11, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arthur, P.; de Garine-Wichatitsky, M.; Valls-Fox, H.; le Page, C. My Cattle and Your Park: Codesigning a Role-Playing Game with Rural Communities to Promote Multistakeholder Dialogue at the Edge of Protected Areas. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Steve, C.; Walker, B.; Anderies, J.M.; Abel, N. From Metaphor to Measurement: Resilience of What to What? Ecosystems 2001, 4, 765–781. [Google Scholar]

- Norgaard, R.B. Ecosystem Services: From Eye-Opening Metaphor to Complexity Blinder. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankford, B.; Watson, D. Metaphor in Natural Resource Gaming: Insights from the River Basin Game. Simul. Gaming 2007, 38, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M.A. Sparkling Fountains or Stagnant Ponds: An Integrative Model of Creativity and Innovation Implementation in Work Groups. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 51, 355–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannino, A.; Ellis, V. Activity-Theoretical and Sociocultural Approaches to Learning and Collective Creativity: An Introduction. In Learning and Collective Creativity; Sannino, A., Ellis, V., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wietske, M.; Furber, A.; Adamowski, J.; Zhou, Q.; Mayer, I. Exploring the Potential Impact of Serious Games on Social Learning and Stakeholder Collaborations for Transboundary Watershed Management of the St. Lawrence River Basin. Water 2016, 8, 175. [Google Scholar]

- Joanne, C.; Angarita, H.; Perez, G.A.C.; Vasquez, D. Development and Testing of a River Basin Management Simulation Game for Integrated Management of the Magdalena-Cauca River Basin. Environ. Model. Softw. 2017, 90, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Jean, S.; Medema, W.; Adamowski, J.; Chew, C.; Delaney, P.; Wals, A. Serious Games as a Catalyst for Boundary Crossing, Collaboration and Knowledge Co-Creation in a Watershed Governance Context. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 223, 1010–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafai, Y.B.; Burke, Q. Constructionist Gaming: Understanding the Benefits of Making Games for Learning. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 50, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roger, E.; Smith, S. From Playing to Designing: Enhancing Educational Experiences with Location-Based Mobile Learning Games. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2017, 33, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Loizos, H.; Jacobs, C.D. Crafting Strategy: The Role of Embodied Metaphors. Long Range Plan. 2008, 41, 309–325. [Google Scholar]

- Johan, R.; Victor, B. Towards a New Model of Strategy-Making as Serious Play. Eur. Manag. J. 1999, 17, 348–355. [Google Scholar]

- Hmelo, C.E.; Holton, D.L.; Kolodner, J.L. Designing to Learn About Complex Systems. J. Learn. Sci. 2000, 9, 247–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, G.; Statler, M.; Flanders, M. Developing Practically Wise Leaders through Serious Play. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2007, 59, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, S.; Oliver, D. Facilitating Serious Play. In The Oxford Handbook on Organizational Decision-Making; Hodgkinson, G.P., Starbuck, W.H., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 475–494. [Google Scholar]

- Hinthorne, L.L.; Schneider, K. Playing with Purpose: Using Serious Play Enhance Participatory Development Communication in Research. Int. J. Commun. 2012, 6, 2801–2824. [Google Scholar]

- Klaus-Peter, S.; Geithner, S.; Woelfel, C.; Krzywinski, J. Toolkit-Based Modelling and Serious Play as Means to Foster Creativity in Innovation Processes. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2015, 24, 323–340. [Google Scholar]

- Swyers, E.L. Investigating Learner Beliefs Using the Lego Serious Play Method. Master’s Thesis, University of Waterlooand and the Universität Mannheim, Waterloo, ON, Canada, Mannheim, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Irene, G.; Flores, A. Using Student-Made Games to Learn Mathematics. Primus 2010, 20, 405–417. [Google Scholar]

- Jon, C.K.; Rule, A.C.; Forsyth, B.R. Mathematical Game Creation and Play Assists Students in Practicing Newly-Learned Challenging Concepts. Creat. Educ. 2015, 6, 1484–1495. [Google Scholar]

- Joli, S. A Game Design Assignment: Learning About Social Class Inequality. Horizon 2016, 24, 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- D’Aquino, P.; Le Page, C.; Bousquet, F.; Bah, A. Using Self-Designed Role-Playing Games and a Multi-Agent System to Empower a Local Decision-Making Process for Land Use Management: The Selfcormas Experiment in Senegal. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2003, 6, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Arnab, S.; Berta, R.; Earp, J.; de Freitas, S.; Popescu, M.; Romero, M.; Stanescu, I.; Usart, M. Framing the Adoption of Serious Games in Formal Education. Electron. J. e-Learn. 2012, 10, 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Cheok, A.D.; Hwee, G.K.; Wei, L.; Teo, J.; Lee, T.S.; Farbiz, F.; Ping, L.S. Connecting the Real World and Virtual World through Gaming; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Proulx, J.N.; Romero, M.; Arnab, S. Learning Mechanics and Game Mechanics under the Perspective of Self-Determination Theory to Foster Motivation in Digital Game Based Learning. Simul. Gaming 2016, 48, 81–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Maele, D.; Van Houtte, M.; Forsyth, P.B. Introduction: Trust as a Matter of Equity and Excellence in Education. In Trust and School Life; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, C.D.; Matt, S. Toward a Technology of Foolishness: Developing Scenarios through Serious Play. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2006, 36, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. The Technology of Foolishness. In Ambiguity and Choice in Organizations; March, J.G., Olsen, J.P., Eds.; Universitetsforlaget: Bergen, Norway, 1979; pp. 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, T. Slow Serious Games, Interactions and Play: Designing for Positive and Serious Experience and Reflection. Entertain. Comput. 2016, 14, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensky, M. Students as Designers and Creators of Educational Computer Games: Who Else? Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2008, 39, 1004–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrea, V.; Marchetti, E. Make and Play: Card Games as Tangible and Playable Knowledge Representation Boundary Objects. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 15th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies, Hualien, Taiwan, 6–9 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Single User | Multiple Users | |

|---|---|---|

| Single resource | S03, S06, S10 | T03 |

| Multiple resources | S01, S02, S04, S05, S07, S08, S09, S011 | T01, T02 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lankford, B.A.; Craven, J. Rapid Games Designing; Constructing a Dynamic Metaphor to Explore Complex Systems and Abstract Concepts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177200

Lankford BA, Craven J. Rapid Games Designing; Constructing a Dynamic Metaphor to Explore Complex Systems and Abstract Concepts. Sustainability. 2020; 12(17):7200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177200

Chicago/Turabian StyleLankford, Bruce A, and Joanne Craven. 2020. "Rapid Games Designing; Constructing a Dynamic Metaphor to Explore Complex Systems and Abstract Concepts" Sustainability 12, no. 17: 7200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177200

APA StyleLankford, B. A., & Craven, J. (2020). Rapid Games Designing; Constructing a Dynamic Metaphor to Explore Complex Systems and Abstract Concepts. Sustainability, 12(17), 7200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177200