1. Introduction

It has become commonplace to start academic and policy papers on the future of cities with the observation that, nowadays, the majority of the world population lives in cities and that this trend will continue in the future. This triumph of the city [

1] is not only based on quantitatively outnumbering, but also on qualitatively outperforming all other places. Neoliberal policy mantras emphasise the crucial role of cities in providing the appropriate ecosystem for businesses to be competitive in global markets [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Social liberals also stress the opportunities that cities provide for a better quality of life through cultural diversity. Cities are seen as the breeding ground for socially inclusive and sustainable policy initiatives. If mayors ruled the world, the perilous challenges of our time, like climate change and poverty, would be handled better [

7].

This success of cities in relation to economic performance, political leadership, and defining ethical standards is now being challenged. The interests and identities of the metropolitan elites increasingly diverge from the rest of the country. Continued economic globalisation generates increasing inequalities between cities and between groups within cities. This also puts additional strains on the relation between cities and their neighbouring regions. The shift in focus of neoliberal policies from strengthening the competitiveness of individual cities to innovative regional networks and production chains makes cities dependent on ever larger metropolitan regions. This necessitates increasing cooperation between urban and regional politicians, who frequently do not share their economic and social liberal outlook, as is reflected in the support for populist politicians in the provinces [

6,

8,

9]. This anti-liberal counterrevolution opposes not only the growing wealth of the urban elites compared to the declining economic prospects of the rest of the population, but also opposes the cosmopolitan identities and liberal social values which legitimise these urban centred policies. As this shift from economic to ecological policies occurs, these divisions between the urban elites and the rest of country deepen. Policies to reduce CO

2 emission based on renewable energy and the transformation from a wasteful linear to a more circular economy, will be primarily realised outside the cities and thus further strain the relation between cities and their neighbouring regions [

10].

This paper analyses the changing character of the relations between cities and their neighbouring regions. This is linked to the transformation of the traditional role of territorial states by decades of neoliberal globalisation and the growing importance in recent years of international policies to tackle global environmental problems. Globalisation was based on the neoliberal erosion of territorial regulation and a concomitant decline of national redistributive policies. Both neoliberal and climate change policies tend to polarise the relation between cities and the rest of the country. This feeds the surge in anti-urban “populism” and further undermines the capacities of the nation state to control its own territory. The combination of these global challenges and territorial fragmentation is beginning to undermine the historic role of the nation state as the cornerstone of modern society. For some, this development is reminiscent of the political arrangements in the Middle Ages which preceded the emergence of the modern nation states [

11,

12,

13,

14]. The Middle Ages are traditionally used as the counter-image of modernity. Following the conceit of Enlightenment philosophers, the evils of these “Dark Ages” are used as a foil to highlight subsequent social, economic, and political progress since the Age of Reason. The current crises in modern societies and the loss of faith in further modernisation to solve our global problems is beginning to render the Middle Ages in a different, and more positive, light. Re-examining and reconceptualising the Middle Ages can help us to better understand how a political system can operate which is not dominated by sovereign territorial states. This is of course only one of many possible futures as for a resurgence in power of nation states is also a distinct possibility which has widespread support, as for instance indicated by the election of Donald Trump and the vote for BREXIT.

In line with the goal of this special issue on “The political economy of home: settlement, civil society, and the (post-)global eco-city,” this paper focusses not on the detailed technical transformations necessary to make the 21st century cities more sustainable. Instead, this paper will engage in an extended reflection on the political transformations related to the changing role of cities in the change from neoliberal globalisation, to a more locally and regionally rooted circular economy and sustainable society as discussed in the call for this special issue [

15]. This can be done from many different perspectives. The perspective adopted in this paper for this special issue is that of neomedievalism. However, neomedievalism is one of many possible ways of how the future could develop and there are many different types of neomedievalist futures possible. This paper explores how a more neomedievalist perspective can help us to better understand the possible development towards a more sustainable urban future. This has consequences for the methodology and design of this more conceptual paper which makes it different from papers reporting on detailed empirical studies. The broad social and political changes through which the role of cities and their neighbouring regions has changed during the formation and transformation of the territorial nation state. Here we focus on how the Middle Ages are used to conceptualise these changes. It analyses how the changes in the relations between cities, their regions, and the territorial state are reflected in their appreciation and conceptualisation of the Middle Ages. The focus of this paper is thus on how the changing conceptualisation of the Middle Ages is linked to changes in the development of society.

First, the conceptualisation of the Middle Ages as the contra-image of modernity and cities as the sparks for the development towards our modern society are discussed. This is supported by the writings of some key thinkers on the relation between social development who focus on the relations between cities and territorial powers. These developments culminated in the formation of modern states in which cities were subjugated by territorial policies to integrate and homogenise national territories. These modernist conceptualisations of territorial state sovereignty have been challenged by globalisation. State sovereignty is now challenged by ever more complex relations between states, cities, and many other global and regional centres of power. This has sparked a renewed interest in the Middle Ages when states functioned in a complex layered system, in which weak territorial rulers operated in a complex political forcefield of local lords, self-governing cities, dynastical networks, and central ecclesiastic control. Neomedievalism is one of the conceptualisations used to reconceptualise the role of nation states towards other powers. This is based on how (neo)medievalism is conceptualised in academic literature. The general characteristics of prospective neomedieval political systems are discussed in more detail and applied to the regulatory challenges faced by neoliberalism. The focus of the latter has shifted in recent years from the competitiveness of cities to that of metropolitan regions, where diverging urban and provincial interests hamper neomedievalist coordination. Besides this neoliberal form of neomedievalism, there is also an alternative neomedieval urban future emerging in which metropolitan regions play a crucial role in the transformation to a more circular economy. This discussion, in the last part of this paper, centres first on the problems of the transition to a more circular economy. The complex and multiscale geographical environment is a critical context for this transformation. A neomedievalist perspective can contribute to the better understanding and management of such complexity and particularly the involvement of many political actors across a variety of different scales. Such a process could overcome the current polarisation in metropolitan regions driven by neoliberal policies and assist in the transition to a more sustainable society and a more circular economy.

3. Neomedievalism

It is beyond the scope of this paper to analyse the actual complexities and multi-layered character of the politics in the Middle Ages. These were based on complex interlocking power systems, ranging from individual merchants and noble men, to continental networks, like the German Hanse, and intercontinental territories, like the Habsburg empire [

32]. The organisation of these complex political relations between different actors and scales changed over time and differed widely between different areas. Despite these differences, they all showed that the nation state-based political system is not the only way in which the politics in a large area can be organised. Instead of focusing on the decline and fragmentation of the current nation state-based system, some academics therefore make comparisons to the Middle Ages to better understand how a political system can function which is not dominated by nation states.

Neomedievalism is used to characterise a possible form of political organisation, which could emerge when the centralised territorial coordination of nation states would continue to fragment, and urban networks would further increase their significance. According to Jan Zielonka [

11], state territorialism and neomedievalism are based on opposing principles.

“The former is about concentration of power, hierarchy, sovereignty, and clear-cut identity. The latter is about overlapping authorities, divided sovereignty, diversified institutional arrangements, and multiple identities. The former is about fixed and relatively hard external borderlines, while the latter is about soft-border zones that undergo regular adjustments. The former is about military impositions and containment, the latter about export of laws and modes of governance” [

11].

Hedley Bull used neomedievalism already in 1977 to characterise a possible scenario of the future development of the international order. Neomedievalism is not the most likely, but one of several possible futures. He discussed first several state-based scenarios. In contrast, in his neomedieval scenario there would not be a central authority or sovereign states, but a political system with a multitude of authorities both below and above the scale of the nation state, none with sovereign power.

“If modern states were to come to share their authority over their citizens, and their ability to command their loyalties, on the one hand with regional and world authorities, and on the other hand with sub-state or sub-national authorities, to such an extent that the concept of sovereignty ceased to be applicable, then a neo-mediaeval form of universal political order might be said to have emerged” [

33]. If such a neomedieval scenario would become reality, the political loyalties of inhabitants of for instance Glasgow would fragment between local, Scottish, UK, EU, and UN authorities, without the government in London having primacy or being able to exercise sovereignty [

33].

Such a mosaic of multiple overlapping and conflicting allegiances will be difficult to coordinate. This necessitates a secular alternative to Christianity as a normative cohesive framework and the Catholic Church as an overarching arbitrator. During the Middle Ages, the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor had some limited form of central supervision. They had some partial and competing regulating powers, not only over territorial states, but also over local authorities, cities, religious organisations and guilds. Neomedievalism “

promises to avoid the classic dangers of the system of sovereign states by a structure of overlapping authorities and criss-crossing loyalties that hold all peoples together in a universal society, while at the same time avoiding the concentration of power inherent in a world government” [

33]. All political actors are in a neomedievalist structure part of an overarching global society, but this is not based, as during the Cold War, on institutionalised political relations between sovereign states, but must rely more on a moral authority grounded in shared values and attitudes [

10,

11,

13,

34,

35,

36,

37]. This can be based on different, or even competing, value systems, like neoliberal economic dogma, or on a normative framework centred on sustainability. These different value systems can focus on different spatial frameworks, like the European Union, or the entire world.

Towards an European Neomedieval Empire?

The importance of scale is also stressed by Jan Zielonka [

11], who is like Hedley Bull sceptical of the emergence of neomedievalism in the whole world. Territorial states are still important and transnational organisations are hardly gaining power. The recently growing influence of national populist politicians tends to strengthen the position of nation states towards international organisations. Neomedievalism is according to Zielonka less a global, but more a European phenomenon. The European Union has over time largely developed akin the neomedieval scenario. The EU in Brussels operates in a multipolar and multi-layered system of overlapping authority and multiple loyalties. The European Commission, Council, Court, and Parliament share power and loyalties with the UN, the US dominated NATO, and EU member states. The sovereignty of the member states has eroded and is losing out to EU policies and regulations, which increasingly directly affect urban and regional authorities [

11,

14].

Despite some centralisation of control, the EU is far from sovereign. Member states and local administrations have ample opportunities to formally opt-out, ignore, or only partly implement EU policies and regulations. The EU thus resembles more a neomedieval empire than a Westphalian super state. This corresponds with the lack of democratic legitimacy at the EU level. Instead through the “voice” option in the form of democracy, EU is legitimised more through these “exit” options from centralised control the EU tolerates like a neomedieval empire [

11]. In contrast, “exit” strategies pose an existential threat to territorial states which depend on uniformisation and hierarchical control. “Exit” strategies menace the assumed coherence between society, territory, and political deliberation, which legitimises the nation state. As was discussed earlier, this can also be seen as part of a territorial trap hindering political thinking about the appropriate scale at which shared communal interests legitimises the production of public goods. Legitimacy depends on the coherence between the community and territory people identify with, and the public space in which interests are balanced, through debate and democratic representation. These hardly exist at the European level and are increasingly challenged at the national level through the polarisation between cosmopolitans in cities and provincials in the rest of the country [

11,

19].

4. Neoliberal Competitiveness Driving Neomedieval Fragmentation

The current driving force behind this fragmentation of the nation state and the emergence of competing centres of power is the neoliberal preoccupation with competitiveness. This focused initially on the deregulation of the economy, but has over the last decades permeated the whole of society. Being outstanding in the competition with others has become the driving force in modern society. According to Andreas Reckwitz [

4], we are now living in a society of singularities. This new form of modernity replaces industrial modernity, which has dominated much of the twentieth century. The focus on standardisation and homogenisation has over the last decades been replaced by a focus on particularisation and differentiation. Individualisation and globalisation have become key characteristics of this late modernity, liquifying the societal and territorial structures of the previous period into the direction of a neomedieval form of political fragmentation. In recent years, the legitimacy of the dominant neoliberal doctrine is being undermined by increasing social and economic polarisation.

During industrial modernity, the social peace in the nation state was based on improving the conditions of the working class and the expansion of the middle class. The transformation to late modernity triggered by the loss of competitiveness of Western industries, degraded large sections of the skilled manual workers into a precariat doing temporary routine jobs [

4]. The educated new middle classes, primarily pursuing professional careers in cities, not only profited from globalisation, but also incorporated competitiveness in their normative framework and worldview. This competition is based on the winner-takes-all principle. The losers in the competition lose out not only materially, but they are also marginalised and excluded as inferior and abject [

4]. The clinging to a traditional way of life, short-termism, an instrumental attitude to work, and unhealthy habits of the precariat result in an almost physical aversion by the new middle class. The offensive vulgar bodies of the precariat are contrasted with the fit, healthy, and mobile bodies the new middle class value so much [

4,

6,

38,

39].

This class polarisation is strengthened through spatial segregation. Urban communities emerge based on lifestyles which provide a suitable environment for the new middle class to pursue their individual life plans. The gentrification of some neighbourhoods within cities excludes the urban precariat and migrants from this urban community [

40]. In the provinces, the livelihood strategy of the precariat relies on their position in the local community. This provides a social safety net, consisting of nearby family and friends, which can help to alleviate their mounting problems in daily life. This form of localism is frequently linked to traditional forms of nationalism and the rise of populism [

4,

5,

37,

40].

The Competitiveness of the Metropolitan Region and Polarisation

At the same time as the polarisation between urban and provincial communities increases, the zones outside the cities have become more important for the success of the urban economy [

10]. Cities increasingly depend on the active cooperation of non-urban municipalities to strengthen the complementarity in metropolitan networks and further increase their attractiveness and competitiveness. The areas outside the cities can provide the metropolitan region with room for urban functions in order to ease pressures on urban areas. They can, for instance, accommodate distribution centres, or new housing estates. Not only the quantity of space available, but also the quality of areas outside cities can strengthen metropolitan regions. They can provide cities and their inhabitants with very different, but complementary amenities and utilities, like residential and recreational facilities, but also with high-quality business services and manufacturing. Non-urban areas can also accommodate many different lifestyles, ranging from the exuberant to the ecological. Non-urban areas not only quantitatively add volume to metropolitan networks, they can also make a significant qualitative contribution to metropolitan networks [

41,

42,

43,

44].

The growing importance of non-urban areas for the economic competitiveness of metropolitan networks challenges the traditional economic and political dominance of cities over their surrounding areas. The urban periphery gains a more central position in metropolitan networks. This gives non-urban administrations a strong bargaining position towards cities when they cooperate in metropolitan regions. For instance, the expansion of the infrastructure between cities is frequently hindered because the dominant stakeholders in local communities fear more the negative externalities, like pollution or unwanted migration, than that they expect to profit from new opportunities, like increased accessibility to urban markets. The development of the competitiveness of metropolitan economic networks depends not only on preventing this kind of passive blocking of infrastructure. It also depends on persuading non-urban administrations to actively participate in the formulation and implementation of more intricate policies to become more complementary to urban areas [

44,

45,

46].

A kind of reformed neoliberal neomedievalism could emerge in metropolitan regions when this growing gap between the interests and identities in the cities and in their surrounding countryside is bridged. But there are other neomedievalist urban futures possible. The current economic and socio-political fragmentation and polarisation can also be accommodated in an alternative, more sustainable neomedievalist arrangement.

5. A Neomedieval Route towards a Circular Economy?

The areas outside the cities have not only become more important for policies stimulating neoliberal competitiveness in metropolitan regions. These areas between cities are also crucial for the transformation to a more sustainable society. Not only as sites for a more sustainable agriculture or for solar and wind farms, but as part of metropolitan regions which have the appropriate scale to coordinate the networks of the circular economy [

47,

48]. This coordination in the circular regional economy can transform the neomedieval fragmentation and polarisation, which currently hinder metropolitan regions which are focussed on more neoliberal policies on competitiveness. The shared values on ecological sustainability linked to a more equitable distribution of benefits and costs can create an alternative neomedieval form of integration of actors and institution focusing on distinct locations and operating at different scales. Exploring the outlines of a neomedieval future in the transition to a more sustainable society based on a more circular economy does not mean that such a from of neomedievalism will become reality. Neomedievalism helps to conceptualise a possible scenario along which this possible shift to a more sustainable society could take place. For instance, ESPON (European Spatial Planning Observation Network) uses different scenarios of how this transition could take place [

49]. Others focus on the complexities and diversity of how these transition processes can be governed [

50].

The doctrine of a circular economy focuses on the transformation of the current linear economy which is based on the destructive extraction of raw materials, a polluting production process, and the dumping of the products after consumption. Closing material cycles is the key to a circular economy. This involves transforming all aspects of the production process. Waste management is one route to a more circular economy. Instead of using landfills and incineration, it is better to recycle waste. But recycling tends to decrease the value of the material. Instead of down cycling, it is better to repair products. Products must be redesigned to make them more repairable and durable. The earlier the interventions in the production process, the more sustainable the outcome [

51]. Whereas the dogma of neoliberal global competitiveness has over the last decades transformed metropolitan regions, the new dogma of a circular economy is still more successful in developing and distributing new ideas, than in transforming economic and spatial structures [

52]. Whereas the socio-technic imaginary of neoliberalism is omnipresent, the transformation to circular economy is still limited to some iconic projects and remains largely a dreamscape [

53].

This transformation to a circular economy will transform space and affect different sites and scales in different ways. The territorial state will play a role in this transformation, but it has to be part of a more neomedieval complex political system. Linking different scales and differentiating between areas is crucial to realise this encompassing transformation and to avoid the pitfalls of policies focusing on a single facet of the transformation to a circular economy.

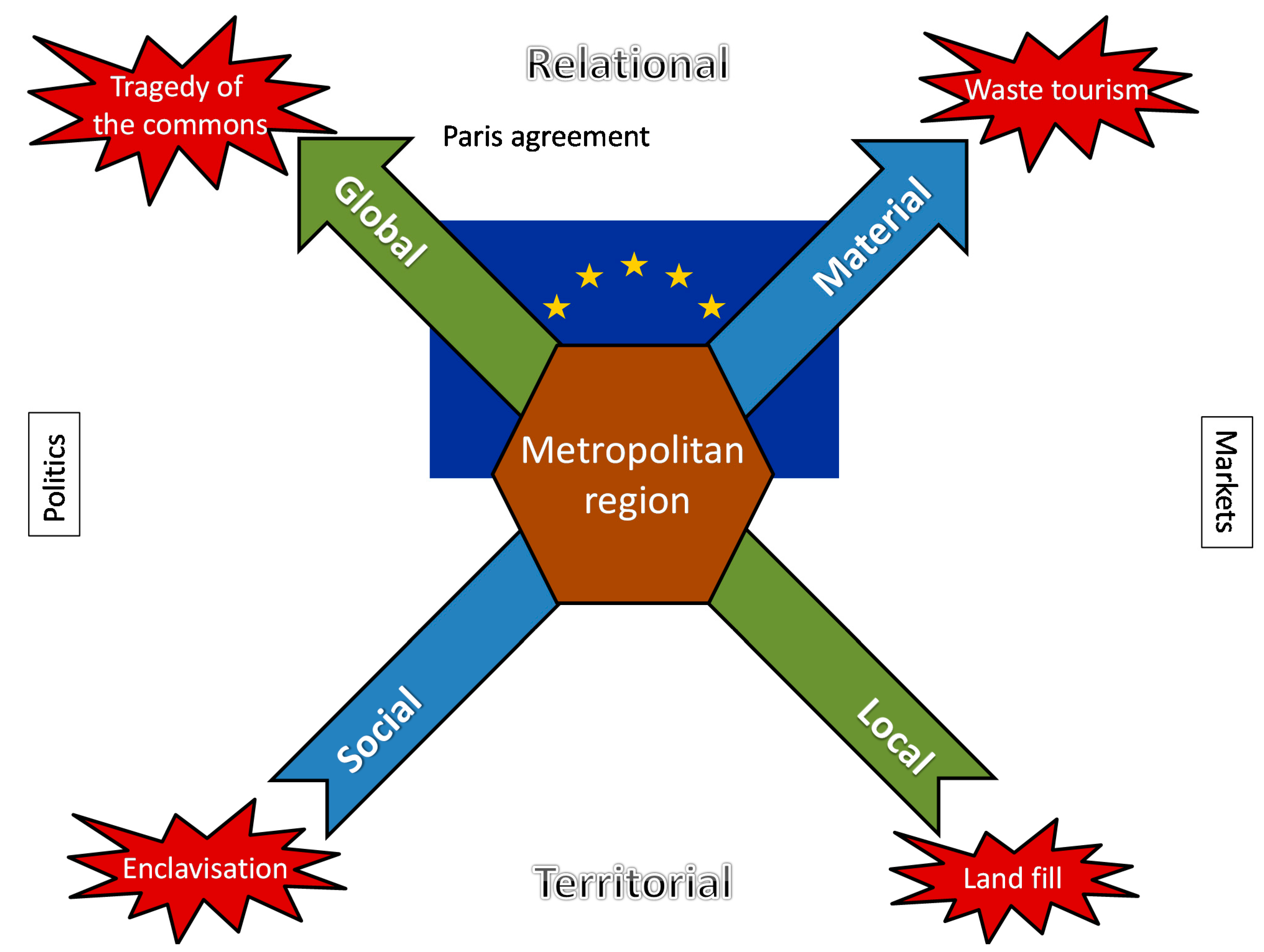

Figure 1 depicts several aspects involved in the transformation to a circular economy and how an overemphasis on one aspect can lead to a pitfall, which can be avoided in the complex, layered, but rooted, neomedievalist metropolitan region.

Figure 1 simplifies the many different approaches and categorisations of the transformation to a circular economy along two dimensions. The first, blue, dimension in

Figure 1 is inspired by the ladder used by many to characterise the various stages of the transformation to a circular economy. The climbing of a ladder from refuse, recycling, repair, to redesign will in the end create a more circular economy [

54]. The first steps of the ladder focus on materials, while at the top the focus is more on the social aspects of the transformation to a circular economy [

48]. The blue dimension in the figure represents these aspects of the transformation to a circular economy not as a ladder, but as a dimension ranging between a fixation on material and a focus on social aspects. The variation in scale at which different material cycles can be closed is another important aspect [

51]. This is depicted in

Figure 1 as the second, green, dimension ranging from the local to the global.

Figure 1 depicts various aspects and approaches to the transformation to a circular economy along these two dimensions. The blue one covers the range between more social to more material approaches, the other, green one, represents the importance of scale, ranging from the local to the global.

Figure 1 shows at each end of these dimensions the pitfalls which must be avoided, and which occur when too much emphasis is given to a single aspect of the transformation to a circular economy. Avoiding these pitfalls calls for a more neomedieval structure in which metropolitan regions will play a vital role. In the next sections, we develop this argument starting from the very local and material aspects depicted in the bottom right corner of

Figure 1. We continue our line of reasoning counter clockwise in this figure to the other pitfalls and discuss in more detail the role of the EU and the importance of metropolitan regions in this neomedievalist restructuring of the role of cities in the transformation to a circular economy.

Waste disposal is the endpoint of the linear economy. Through its distinct material and local character, it is the most conspicuous negative consequence of the linear economy [

51]. Concerns for public health have for centuries driven local authorities to regulate waste disposal. In an agrarian economy, waste was mostly used to fertilise land, but with rapidly growing industrial production, consumer waste was increasingly dumped in landfills. These smelly, polluting, and very visible garbage heaps became early rallying points for environmentalists. This traditional form of waste management could be realised within the institutional territorial framework of the nation state. However, the further recycling and reduction of wasteful production is becoming complex and is difficult to regulate by the nation state. The complexity and growing international dependencies are beyond the control of the nation state. This lack of control can perhaps be resolved through some more neomedievalist forms of integration focussing on flexible urban territories, like metropolitan regions.

The national regulations controlling refuse dumping have over the last decades been augmented by attempts to stimulate recycling. These are much more difficult to regulate through the nation state, which is both too big and too small to regulate the transition to a more circular economy. The complexity and costs of waste separation and its reuse makes the regional scale suitable to organise recycling. Sometimes this upscaling goes further, and waste is exported to be recycled elsewhere. There has emerged an international market for waste recycling. The competitive drive to minimise costs and maximise profits has sometimes resulted in waste collected in rich Western states being exported to peripheral states in the global south. It is officially to be recycled using cheap labour, but it is frequently dumped or incinerated. This “waste tourism” or “waste imperialism” profits from differences in administrative control across borders. It is now increasingly regulated against, by both importing and exporting states [

51]. Controlling these kind of material exports across borders and activities within their territory, befits the traditional regulatory role of states. The international system of sovereign states has much more difficulties in tackling global environmental problems like climate change. This is an example of the “tragedy of the commons” which is based on the mismatch between the benefits companies and sovereign states acquire from the unsustainable linear economy, and the collective costs of global warming nobody can escape from. Regulating to balance these individual benefits and collective costs is difficult in an international system of sovereign states [

48,

55,

56]. Their cooperation in the United Nations is based on a precarious balance between protecting territorial sovereignty and stimulating international relations to address global problems affecting every state. The Paris agreement to contain global warming by reducing greenhouse gas emissions depends on states for implementation. This makes it difficult to avoid this pitfall of this global tragedy of the commons.

5.1. The EU Extending Its Control Outside and Inside Its Territory

The difficulties in implementing these global agreements is used by the European Union to justify increasing its legal authority inside and outside the territory of the EU [

57]. The introduction by the EU of costly new environmental regulations will make production in the EU more expensive. To protect the competitiveness of the European companies, the EU will levy extra taxes on products from outside the EU if these imported products are cheaper while they are produced in states without similar strict environmental standards [

57]. The EU will thus not only increase its authority within its borders, but also extends its control beyond its borders. Industries in other states must accept EU standards or must pay extra duties at the external border of the EU through this carbon border adjustment mechanism [

57,

58]. This appears to be part a neomedievalist restructuring of the international system of sovereign states.

Within its borders, the EU undermines the hierarchical control of its member states. The EU will not only give special support to coal dependent regions, but will also mobilise through subsidies and persuasion local stakeholders and local communities [

57]. Instead of hierarchically controlled fixed competences, the EU relies more on cooperation based on commitment to specific projects. The EU even wants that all “

EU initiatives live up to a green oath to ‘do no harm’” [

57]. This is more like a neomedieval form of politics based on commitment and cooperation to realise specific local projects, than the standardised hierarchical control over a uniform territory.

5.2. From Local Initiatives to Communitarian Metropolitan Regions?

Besides these top-down initiatives to gradually transform the whole of society to a circular economy, there are many bottom-up initiatives. Some devoted individuals want to take direct action with similar minded individuals to make a more radical break with the conventional linear economy through local circular initiatives. They are in danger of falling into the pitfall of enclavisation depicted in

Figure 1, while they tend to focus on internal bonding based on their joint commitment to circularity. Their shared doctrinal world view, combined with their more cosmopolitan identity and green lifestyle, tends to isolate these circular projects from the rest of the local community [

59].

Bonding and pontificating within the congregation of the converted to the circular economy, frequently leads to self-enclavisation of housing and business projects. Being rooted in the local community by developing linkages to other groups and stakeholders is however crucial for the wider application and upscaling of these local circular initiatives [

59]. Like medieval monasteries, activists not only have to bond within their networks, but they also have to reach out to their local communities where people have different ideas and resources. They also have to link up with local and regional administrations, with their own special interests, experts, and knowledge. The success of these circular projects depends on their outside linkages, which legitimise their local circular project horizontally to the local community, and vertically across administrative scales. In these vertical relations, local activists are wary to lose autonomy and idealistic purity, while administrations expect of local activists commitment and rational knowledgeability [

48,

51,

59,

60,

61]. Territories and hierarchies are thus important for these bottom-up local circular economy initiatives to develop and have a wider impact in the transformation to a more circular economy. These locally rooted long-term commitments across scale can spatially converge in metropolitan regions.

“This is an eco-economy which will not only be more adept at sustaining vibrant rural communities and places, but one which will provide the revised socio-ecological functions for the growing and indeed dominant cosmopolitan arenas in which most people live” [

60].

This creates possibilities for more communitarian metropolitan regions [

55,

60]. Instead of being subjected to neoliberal marginalisation, rural areas can provide key services to cities. This enables the linking of different knowledge networks and stakeholders at different scales. The strengthening of these multi-level forms of collaborative governance are primarily coordinated through cooperation based on commitment and shared knowledge. The refocussing on the quality of life for the whole community however also necessitates more hierarchical interventions to strengthening integration and equity within and between territories [

55]. This proposed organisation of these communitarian metropolitan regions is based on a neomedievalist alternative to wasteful modernisation and polarising neoliberalism.

“We need then to plan for a range and diversity of ‘metropolitan countrysides’; ones which are integrated in new ways with regenerative cities. Here then, and indeed very much in part a result of the uneven processes we are exposing in the development of the post carbon transition, we will need to completely explode the modernist and neo-liberalised myth of the rural-urban divide” [

60].

This hope to create a new kind of communitarian metropolitan region is still largely a dreamscape yet to be realised. It is hampered by traditional regionalisms and the rise of provincial populism opposing both neoliberal competitiveness and social liberal environmental policies. Cities depend on their neighbouring regions for the construction not only of business parks, roads, housing estates, and recreation facilities, but also for recycling facilities, wind and solar farms. The necessity to locate the infrastructure for both neoliberal competition and sustainable transitions in the regions outside the cities calls for a kind of neomedieval form of accommodation yet to be realised.

6. Conclusions

In the centuries following the Middle Ages, the development of modern society was conceptualised as increasingly freeing humanity from the medieval constraints holding back societal development. The development of the modern state regulating an ever more homogenous and integrated fixed territory was based on the social logic of industrial modernity. When this became crisis ridden in the late twentieth century, a new form of social logic emerged, based on competition based on singular qualities. Whereas neoliberal globalisation dominates the economy, the competitiveness in late modernity dominates all social spheres through the rise of the new educated middle classes in the cities. The resulting economic and socio-political fragmentation undermined the dominant position and regulatory powers of the nation state, which is no longer the unquestioned dominant political power. After these centuries of integration through the development of modern nation states, there is an increasing interest in alternative political arrangements and perspectives.

Neomedievalism is one such perspective which helps us to look beyond not only the traditional nation state, but also to alternatives to neoliberal globalisation. Neomedievalism thus does not imply a return to the Middle Ages, nor offers a clear-cut vision of the future. Neomedievalism does not suggest a single societal developmental path after the decline of sovereign territorial states. Both a further development of the neoliberal regime, or the transformation to a circular economy, can be governed in a neomedievalist manner. There are of course other types of futures possible, like the revitalisation of a nation states based political system. There are also many types and degrees of neomedievalist futures possible.

In the neoliberal variety, the focus of policies to further promote global competitiveness will shift further from the relation between individual cities and their territorial state, to much more diverse and complex horizontal and vertical relations and dependencies in metropolitan regions. In this neomedievalist political structure, the sovereignty of territorial states will further decline and be challenged by other political institutions which focus more on specific tasks and other spatial scales. This will increase the fragmentation of territorial sovereignty, which will be increasingly difficult to offset by the normative framework based on a global neoliberal economic dogma.

The growing resistance against neoliberal globalisation from both the national populist and the environmentalist movements, makes this type of neoliberal neomedievalism increasingly problematic, especially while these challenges to the neoliberal dogma further polarises the relations between cities and their countryside. This undermines the operation of metropolitan regions which have in recent years become crucial for neoliberal economic policies. It also further fragments the territory of the nation state and destabilises its political institutions. While the legitimacy of these neoliberal policies based on strengthening the competitiveness of metropolitan regions has become very problematic, other, more communitarian types of metropolitan regions have more potential to form the basis of some neomedievalist political structure which can organise the transition to a more circular economy and avoids many of the pitfalls threatening this transition. This form of neomedievalism has the potential to lessen the current polarisation between the cosmopolitan cities, and the provincial populism and traditionalism in more rural areas. Metropolitan regions can organise links across these divides between groups with different interests, identities, and ideas. These more neomedieval organisation of metropolitan regions can create an urban future that is more sustainable. This is only a possibility and hardly a certainty, as this rural-urban divide can easily be deepened by overzealous activists and populist politicians.