The Commodification of Chinese in Thailand’s Linguistic Market: A Case Study of How Language Education Promotes Social Sustainability

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Research Design

- (1)

- To what extent and in which domains is the Chinese language commodified through the linguistic landscape in Chiangmai?

- (2)

- What is the language ideology of local Chinese language learners in Chiangmai?

- (3)

- In what ways might the commodification of the Chinese language affect the sustainability of Thai society?

3.1. Research Methods

3.2. Participants

3.3. Data Collection

4. Findings

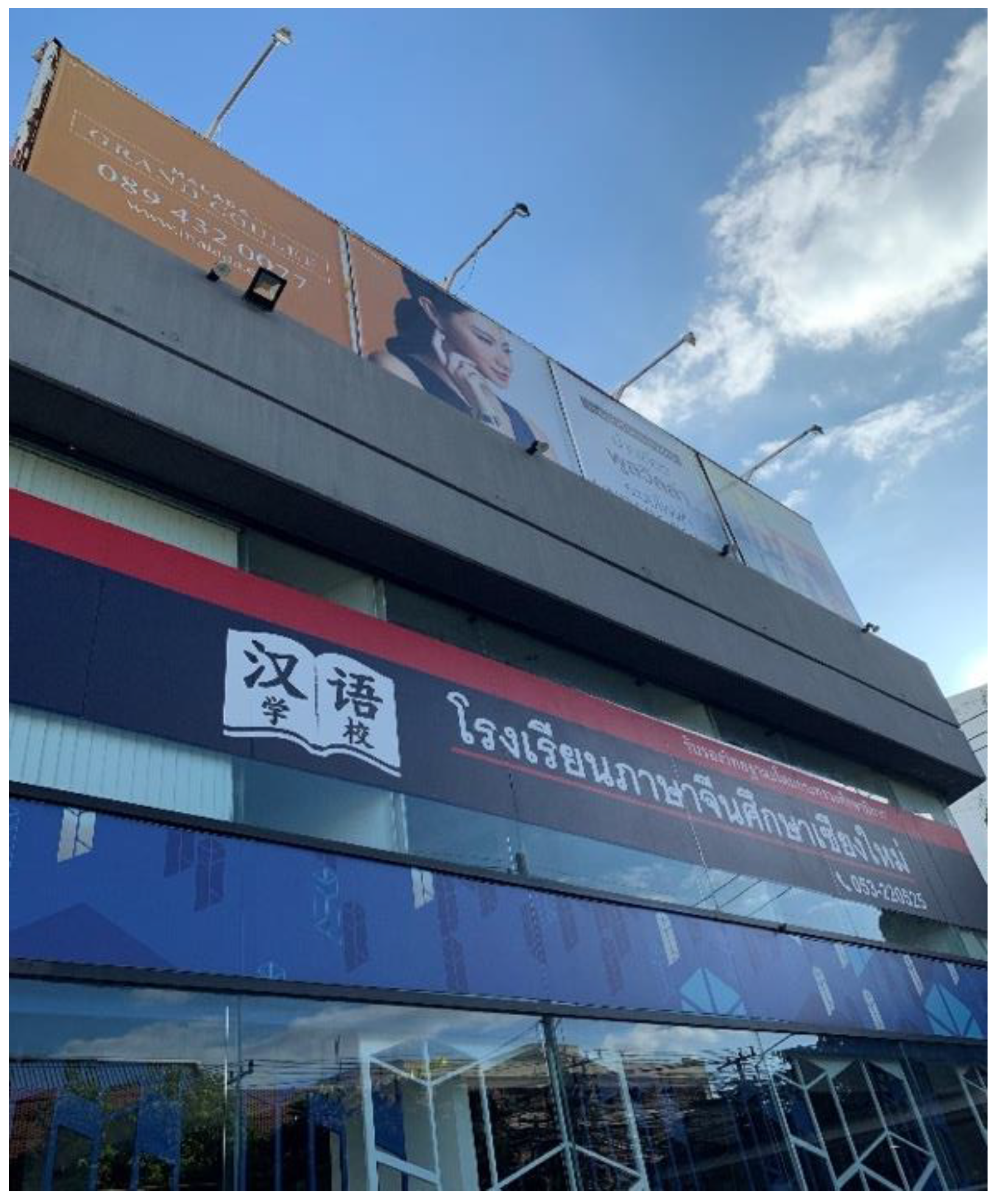

4.1. The Expanding Domain of Chinese Language Commodification

4.2. Ideological Feedback about Language as National Identity or Instrument

(1) Chinese has given me a lot of convenience, especially in my business. If it wasn’t for the fact that I was taught to speak Chinese, a lot of business would be impossible now. The Chinese market is very big now, with a lot of tourists every year. Many of the rich people you see in Thailand are of Chinese descent, like the Central Mall and Charoen Pokphand Group…

(2) The older generations speak southern dialects, such as Minnan and Cantonese. Our generation was adapted to the local society, and was mostly raised speaking Thai and learning Thai in school. Chinese has made it easier for me to do business, because nowadays there are many Chinese tourists, even more than white people. Many of my business customers and my business partners are from China. It (speaking Chinese) makes things very convenient.

(3) My father wanted me to master Chinese, and I am now studying in China. A mastery of language could bring me more opportunities. I don’t speak English well, but in order to be able to study in other countries later, I have to pass the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language).

4.3. The Impacts of the Commodified Chinese Language

(4) In the past, the reason for learning Chinese was that there were Chinese people in the family, but there weren’t many opportunities to use it in life. Now things are different. In the past, there were not many places to learn Chinese, and teaching Chinese is now more accessible than ever. Learners of Chinese in the past would think that Chinese is inferior to English, but today it is different.

(5) Chinese is considered to be an important language in the future, and I was asked to learn Chinese in primary school, but in high school I voluntarily chose to learn Chinese. I chose to study Chinese because I believe I will use it in the future, for example, in my daily life, at school and in travel.

(6) Chinese is important, the Chinese economy is big, and if I graduate, I might be economically independent. I need the scholarship because I don’t want to bother Mom and Dad for the tuition.

(7) I started learning Chinese while working in Bangkok. After graduating from the south for 1 to 2 months, I started working as a clerk at Khun A in Bangkok. Khun himself would study Chinese in his spare time at night, because he had Chinese relatives in his family. He thought I should learn Chinese as well, as it will become an international language in the future. The Chinese are investing more in Thailand, and the various future job opportunities will be better.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cameron, D. Good to Talk? Living and Working in a Communication Culture; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, M. Paths to Post-Nationalism: A Critical Ethnography of Language and Identity; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, M. Globalization, the new economy, and the commodification of language and identity. J. Socioling. 2003, 7, 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H. Language “skills” and the neoliberal English education industry. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2016, 37, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolard, K.A. Simultaneity and bivalency as strategies in bilingualism. J. Linguist. Anthropol. 1998, 8, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujolar, J. Bilingualism and the nation-state in the post-national era. In Bilingualism: A Social Approach; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 71–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.; Lyu, B.; Gao, X. Research on teaching Chinese as a second or foreign language in and outside mainland China: A bibliometric analysis. Asia Pac. Educ. Res. 2018, 27, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung-Yul, P.J.; Lo, A. Transnational South Korea as a site for a sociolinguistics of globalization: Markets, timescales, neoliberalism 1. J. Socioling. 2012, 16, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.F.; Gao, X.A.; Lyu, B. Teaching Chinese as a second or foreign language to non-Chinese learners in mainland China (2014–2018). Lang. Teach. 2020, 53, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganahl, R. Free markets: Language, commodification, and art. Public Cult. 2001, 13, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, M. The commodification of language. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2010, 39, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nair-Venugopal, S. An interactional model of English in Malaysia: A contextualised response to commodification. J. Asian Pac. Commun. 2006, 16, 51–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor, A.M.R. The commodification of English in “Madrid, comunidad bilingüe”: Insights from the CLIL classroom. Lang. Policy 2015, 14, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T. Language ideology, identity and the commodification of language in the call centers of Pakistan. Lang. Soc. 2009, 38, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, X. Commodification of the Chinese language: Investigating language ideology in the Irish media. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosonen, K.; Person, K.R. Languages, identities and education in Thailand. In Language, Education and Nation-Building; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 200–231. [Google Scholar]

- Morita, L. Discussing assimilation and language shift among the Chinese in Thailand. Int. J. Sociol. Lang. 2007, 2007, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, L.C. Language shift in the Thai Chinese Community. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2003, 24, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burin, A.; Boochita, P. Tourism: Still a Reliable Driver of Growth; Bangkok Bank: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Polèse, M.; Stren, R.E.; Stren, R. The Social Sustainability of Cities: Diversity and the Management of Change; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Rethinking Education: Towards a Global Common Good; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Skutnabb-Kangas, T. The globalisation of (educational) language rights. Int. Rev. Educ. 2001, 47, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skutnabb-Kangas, T.; Phillipson, R. A human rights perspective on language ecology. Encycl. Lang. Educ. 2008, 9, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, M.; Duchêne, A. Treating language as an economic resource: Discourse, data and debate. Socioling. Theor. Debates 2016, 139, 156. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimmons-Doolan, S. Language ideology dimensions of politically active Arizona voters: An exploratory study. Lang. Aware. 2011, 20, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimmons-Doolan, S. Identifying and Describing Language Ideologies Related to Arizona Educational Language Policy; Northern Arizona University: Flagstaff, AZ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gorter, D. Linguistic Landscape: A New Approach to Multilingualism; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M. Language ideology and language order: Conflicts and compromises in colonial and postcolonial Asia. Int. J. Sociol. Lang. 2017, 2017, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly-Holmes, H. Analyzing language policies in new media. Res. Methods Lang. Policy Plan. A Pract. Guide 2015, 4, 130. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly-Holmes, H.; Milani, T.M. Thematising multilingualism in the media. J. Lang. Politics 2011, 10, 467–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, Y. Sino-Thai entrepreneurs and the provincial economies in Thailand. Altern. Identities Chin. Contemp. Thail. 2001, 1, 169. [Google Scholar]

- Stroud, C.; Wee, L. Style, Identity and Literacy: English in Singapore; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, S.; Cavanaugh, J.R. Language and materiality in global capitalism. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2012, 41, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R. Outsourced to China: Confucius Institutes and Soft Power in American Higher Education; National Association of Scholars: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. What motivates the spreading of a language. In Chinese Language Globalization Studies; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2011; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Phongpaichit, P. Inequality, wealth and Thailand’s politics. J. Contemp. Asia 2016, 46, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanitcharearnthum, V. Top income shares and inequality: Evidences from Thailand. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blommaert, J. The Sociolinguistics of Globalization; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman, J.; Modan, G. Commodified language in Chinatown: A contextualized approach to linguistic landscape 1. J. Socioling. 2009, 13, 332–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse-Biber, S. Qualitative approaches to mixed methods practice. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Method | Linguistic Landscape Documentary | Questionnaires | Interviews | Online Ethnographies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RQ related | 1 | 1,2 | 2,3 | 2,3 |

| Aim | Analyze the commodification of Chinese in local Thai society | Describe the language beliefs of participants | To understand how interviewees perceive the meaning of Chinese language learning and its impact on their own lives. | |

| Process | Use of iPhone to document the linguistic landscape of Nimman Road, Chiangmai International Airport, and the Inner City | Questionnaires were distributed and collected, coded, and results were calculated. | Selected qualified interviewees, and recorded, translated, and coded their feedback | Accessed, coded, and analyzed content generated by Chinese language learners in forums, discussion groups, and other internet venues. |

| Category | Statements |

|---|---|

| National identity | Language represents a national identity. |

| The law makes a language into an official language of a nation. | |

| School teachers use official language to teach. | |

| Personal identity | Language is a person’s identity. |

| Learning a new language causes trouble for personal identity. | |

| It is a pity if my son or daughter cannot speak my native language. | |

| Language Right | The use of language is a human right. |

| People are encouraged to use dialects and native language. | |

| A language in danger should be saved. | |

| Globalism | Humanity needs a common language. |

| Some languages are dying because they are not useful. | |

| Big countries should spread their language in foreign countries. | |

| Instrumentalism | Learning some languages can help people make more money. |

| Languages are assets for humankind. | |

| I learn a language because it is useful for my career. |

| Number | Description | Method |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chinese language teacher, studied in China for 4 years, Bachelor’s degree in education | Interview |

| 2 | Entrepreneur who has studied and worked in China | |

| 3 | Thai Chinese descendants, owns a company | |

| 4 | High school student, studying in China | |

| 5 | High school student, studying in China | |

| 6 | High school student, studying in Thailand, preparing to study in China | |

| 7 | Businessman, has daughter studying in kindergarten | Online Ethnography |

| 8 | Primary school student | |

| 9 | Employee | |

| 10 | Employee | |

| 11 | Employee | |

| 12 | Student, grandparents were Chinese immigrants |

| Interviewee No. | National Identity | Personal Identity | Language Rights | Globalism | Instrumentalism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | −0.33333 | 1 | −0.66667 | 1.666667 |

| 2 | 0.333333 | 0.333333 | −0.66667 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 1 | −0.33333 | −1 | −1 | 1 |

| 4 | 1 | −0.33333 | −1 | 1 | 1.666667 |

| 5 | −0.33333 | 0.333333 | 1 | 0.333333 | 1.666667 |

| 6 | 0.666667 | −1 | −0.33333 | 1 | 1.666667 |

| 7 | 0.333333 | 0 | −0.33333 | 0.666667 | −1 |

| 9 | 1 | 0.666667 | 1 | −1 | 1 |

| 10 | −0.66667 | 1 | 1.666667 | −1.66667 | 0.666667 |

| 11 | 1.333333 | 0 | −0.66667 | −0.66667 | −0.66667 |

| 12 | 1 | −0.33333 | −0.66667 | 0.666667 | 1 |

| AVERAGE | 0.61 | 0 | 0 | −0.0303 | 0.88 |

| t-test | 0.862 | 0.669 | 0.104 | −0.434 | 2.714 |

| p value | 0.019 * | 0.520 | 0.919 | 0.674 | 0.024 * |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, S.; Shin, H.; Shen, Q. The Commodification of Chinese in Thailand’s Linguistic Market: A Case Study of How Language Education Promotes Social Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187344

Guo S, Shin H, Shen Q. The Commodification of Chinese in Thailand’s Linguistic Market: A Case Study of How Language Education Promotes Social Sustainability. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187344

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Shujian, Hyunjung Shin, and Qi Shen. 2020. "The Commodification of Chinese in Thailand’s Linguistic Market: A Case Study of How Language Education Promotes Social Sustainability" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187344