Abstract

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established in 1967 to promote the integration and creation of new opportunities for citizens of ASEAN member countries. ASEAN member countries have signed mutual recognition agreements on services (including services in the construction industry) since 2005 to facilitate the movement of human resources in ASEAN countries, with engineering services qualifications being one of the eight professional qualification recognition schemes in the region. In particular, a recent trend in the construction industry is the use of building information modeling (BIM). While BIM practitioners are increasing, BIM Practitioner Certifications (BPCs) have not yet been legalized and recognized. This study conducted interviews and a survey with industry experts, finding as a result that the recognition of the competency of BIM practitioners is in demand and needs to be legalized with the recognition of experienced engineers via registration or licensing to include BPCs. This is an important step for removing artificial barriers to the free movement and practice of professional engineers amongst ASEAN countries. Additionally, evidence suggests that the BIM workforce’s benefits only become realizable when BIM certifications are systematic and recognized. Based on the survey results and expert interviews, BIM practitioners are certificated according to three main roles: manager, coordinator and modeler. Finally, a framework for issuing BPCs is proposed in this study. This study’s results are expected to contribute significantly to the success of BIM practitioner mobility among ASEAN member countries for sustainable economic development.

1. Introduction

Regional integration plays a crucial role in driving economic and social development in many regions of the world. The member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) have signed a mutual recognition agreement on engineering consultancy services (including services in the construction industry) since 2005 for recognizing the development of human resources. ASEAN Mutual Recognition Arrangements (MRAs) promote the cross-border mobility of professionals through mutual recognition of authorization, licensing or qualifications certificated by professional service suppliers [1]. As such, each ASEAN engineer has the opportunity to work in another ASEAN member country as long as he or she is recognized and granted the registration certificate as an ASEAN Chartered Professional Engineer (ACPE), which is issued by the ASEAN Federation of Engineering Organizations (AFEO) or the ASEAN Chartered Professional Engineer Coordinating Committee (ACPECC). As of March 2018, there were 2876 engineers registered as ACPEs, and the ASEAN Architect Register listed 475 architects [2]. Preexisting recognition standards, such as the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) engineering initiative, contributed to the relatively quick establishment of the ASEAN engineer framework [3]. Several simulation analyses have been conducted to investigate the impact of recognizing labor mobility agreements among ASEAN member countries [1,2]. The results indicated that labor mobility and recognition in regulated professions bring opportunities for labor and have a positive impact on economic development. Other previous studies have proven that individual competencies are the fundamental building blocks of an organization’s competency. Furthermore, for human resource planning, management is the key to the development of a firm [4,5].

Building information modeling (BIM), a relatively new trend, has played an essential role in the construction industry nowadays. BIM has become an invaluable process enabler for modern architecture, engineering and construction [6]. BIM-enabled projects are more productive, predictable and profitable by upholding the integrity and transparency of information across the life cycle of built assets [7]. Recognizing the benefits of BIM, public sectors in Europe, the United States, the United Kingdom and some Asian countries started mandating BIM in the early twenty-first century [6]. Integrating BIM into the construction industry is increasing for sustainability purposes [8]. BIM practitioners are considered similarly important to specialists in other fields such as construction surveying, planning, design, field supervision and quantity surveying. BIM implementation contributes to optimizing energy efficiency and investment costs [9]. Furthermore, BIM is considered a supplement to expertise in the construction industry. While other fields have been included in Mutual Recognition Arrangements as engineering consultancy services (including services in the construction industry) since 2005, BIM practitioners are not recognized yet. This current status leads to the overarching questions:

- (i)

- What is the demand of the BIM workforce on certifications and competency recognition nationally and regionally?

- (ii)

- What are the benefits of legalizing a BIM practicing certification?

- (iii)

- Should authorities enact recognition agreements for BIM practitioners in removing barriers to the free movement and practice of BIM practitioners amongst ASEAN countries?

- (iv)

- What is the solution for regional BIM practitioner mobility?

Kim et al. indicated that BIM adoption requires flexible work processes through BIM human resources training [10]. Some ASEAN countries lack BIM experts and BIM practitioners. This has led to high demand for BIM practitioners in ASEAN countries as well as BIM practitioner mobility in the region. This raises the issue of whether ASEAN member countries have regulations or intentions to implement a BIM certification system for quality assurance of construction activities. When hiring BIM personnel, it is important to consider a candidate’s level of BIM proficiency, and a BIM certificate can well serve this purpose [11]. In addition, based on the BIM needs of a company, practitioners with different levels of BIM proficiency could be hired, and a corresponding management system could be developed [4]. Previous studies show that a professional engineer certificate brings engineers career opportunities and promotions [1]. However, regional and international recognition of professional engineering certificates faces critical challenges in creating and revising domestic policies, regulations and processes to make them consistent with the spirit of mutual recognition [12]. Lack of BIM regulations is one critical barrier for cross-nation recognition of BIM practitioners [13,14]. This leads to the necessity of national and international legalization of BIM Practitioner Certifications (BPCs). Regional agreements for the recognition of BIM experts are currently in demand in the construction industry to promote collaboration among ASEAN member countries.

Several BIM studies have mentioned individual BIM competencies and other equivalent roles in construction projects [4,11,15]. However, there is a lack of research on systematic BIM certification, which reinforces the confidence of the construction industry in using BIM human resources in BIM-adopted construction projects. The gap in the current status of BIM adoption accelerates the need for a critical review of the legal issues associated with BPC recognition in the construction industry to address the associated legal issues and discuss how current regulations could be improved.

This study was conducted with four objectives: (i) to identify the benefits of recognition agreements for BIM practitioners in removing artificial barriers to the free movement and practice of BIM experts amongst ASEAN countries, (ii) to identify the current status of BIM practitioner realization in the ASEAN countries and the various issues in regional labor mobility, (iii) to evaluate the demand of the BIM workforce on certifications and competency recognition nationally and regionally and (iv) to propose a framework for the issuance of BIM certifications. The outcome of this proposed framework for BPC issuance will provide a temporary analysis of the potential agreements among ASEAN countries that are practical and feasible for future BIM human resource recognition.

2. Research Method

To meet the above-mentioned objectives, the current status of BIM engineer mutual recognition as well as BIM adoption in ASEAN were reviewed. From there, fifty-five journal papers, conference papers and reports relevant to BIM competency and engineering mobility recognition were collected and analyzed. The agreements among ASEAN member countries and domestic regulations on engineering practice certificates were reviewed as well. BIM competencies were analyzed to the construction projects’ BIM requirements. Through this, the qualification criteria were identified through the required BIM competencies.

The application of BPCs cannot be justified and the envisioned benefits cannot be enumerated without understanding the current ASEAN professional engineering certification. Therefore, a semistructured interview approach was adopted to determine the necessity of BPCs and BIM individual competencies. Experts were selected based on their general involvement and experience in labor mobility policy and particular involvement and experience with BIM practitioners. The interviews aimed to explore the perspectives and experiences of researchers and experts who have experience in engineering practice management among ASEAN member countries and, particularly, in the construction industries in those countries. This method sheds light on the insufficient transition from research into practice [16]. The focus of the interviews was on the existing problems and challenges and the proposed directions for recognizing the capacity of BIM practice certifications to create favorable conditions for ASEAN engineer mobilization. The targeted interviewees included government authorities, researchers and leaders of professional associations who have experience in engineer certifications and regulations in ASEAN member countries.

The questionnaire for the semistructured interview consisted of twenty initial questions, with the interviews recorded and transcribed. During the semistructured interview, the questions were developed, and the interviewees were encouraged to provide their opinions when appropriate to the research objectives. It was also possible to ask additional questions if the BIM expert raised issues that the interviewer had no prepared questions for and to allow the experts to speak in more detail on BPCs that the researcher raised as well as introduce solutions for BPC issuance that were relevant to the research theme. The primary entities affected by general labor mobility and specifically BIM practitioner mobility were also discussed. In this phase, the researchers were prepared to change the order of the questions depending on the conversation flow. Furthermore, sixteen individuals were interviewed to identify perspectives on BIM engineer certifications and competency. These interviewees have experience in different countries in ASEAN, thus providing diverse opinions. All the information and data gathered were qualitative in nature.

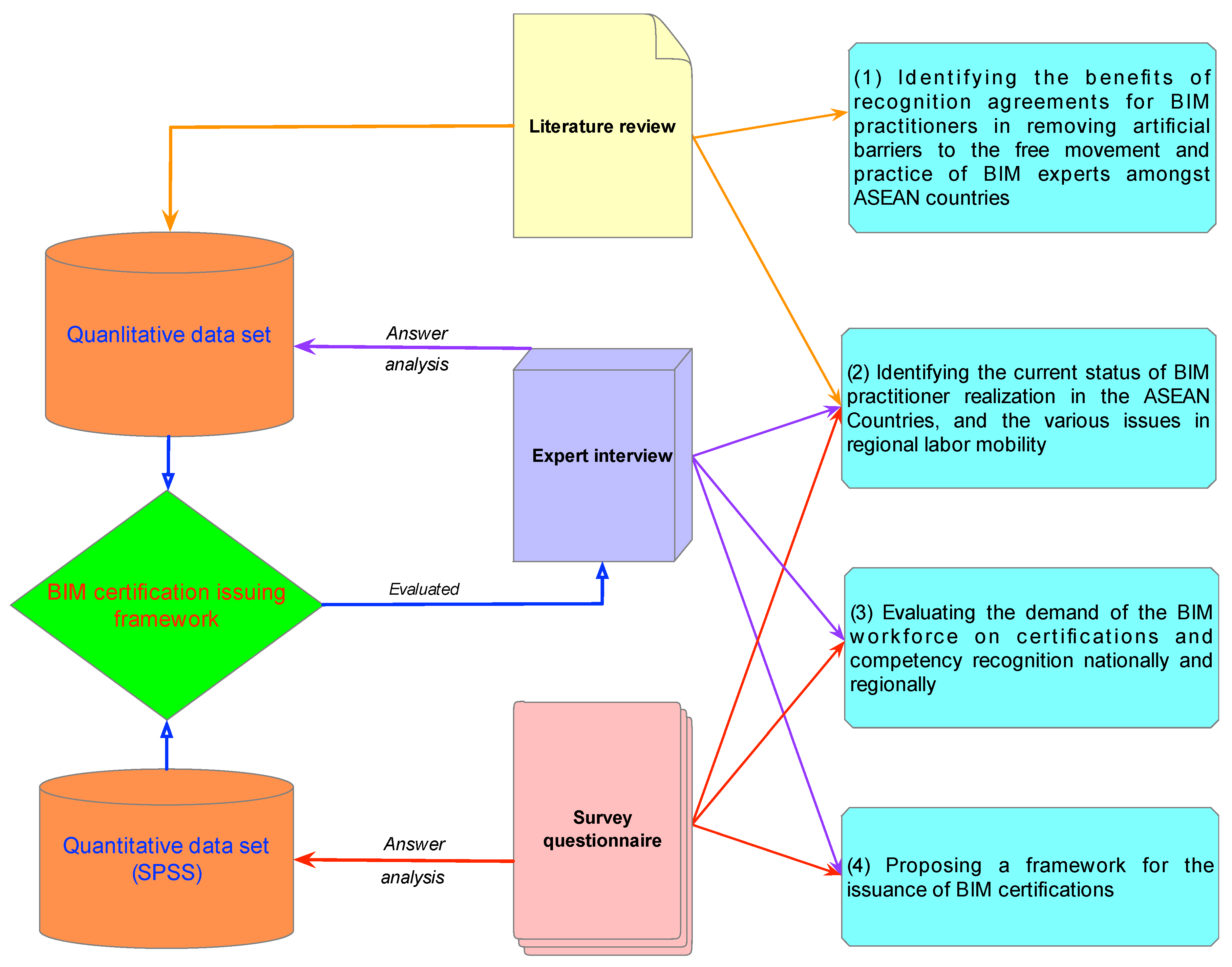

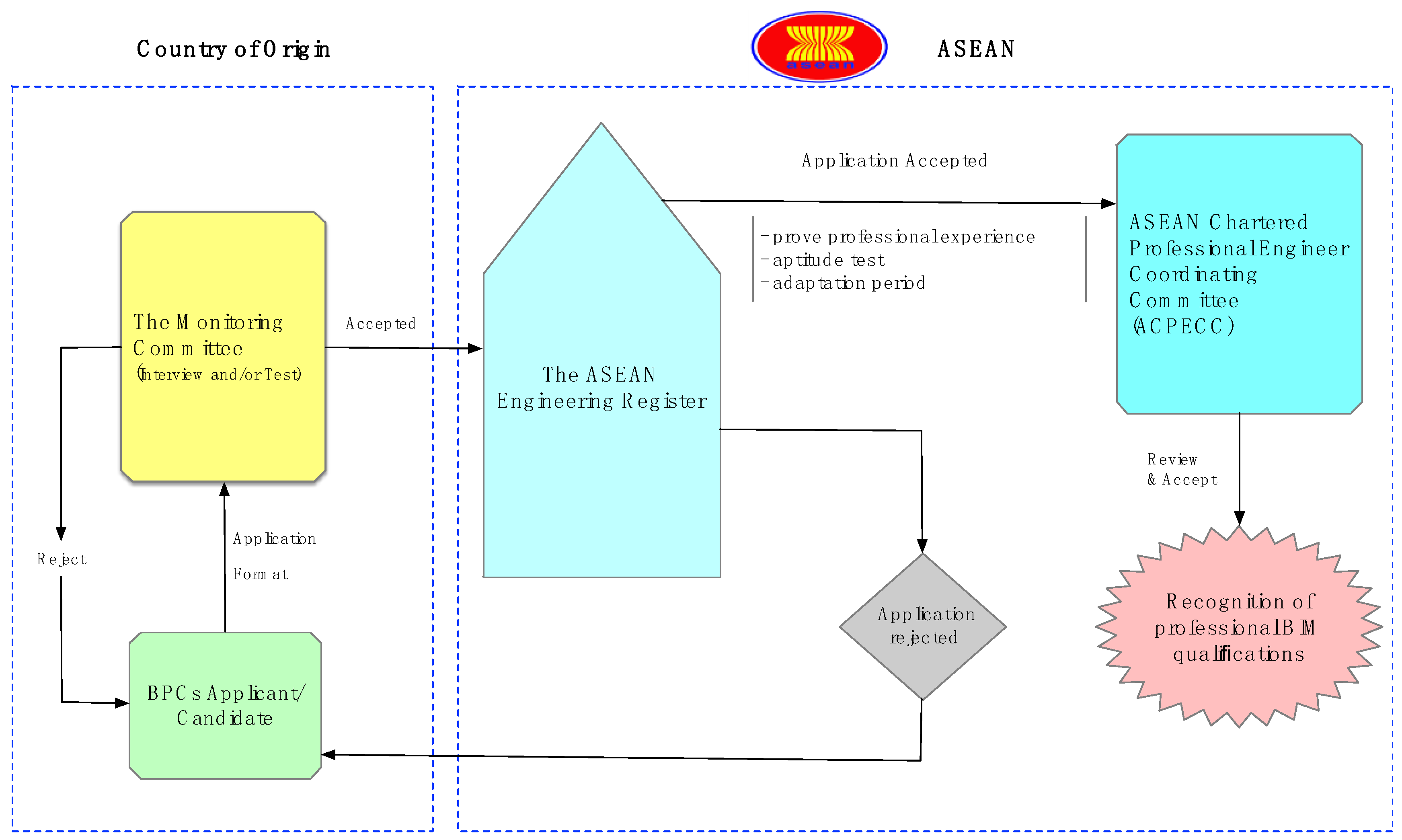

After reviewing the literature and analyzing the experts’ answers, a questionnaire survey was conducted targeting practitioners working in the construction sectors in ASEAN member countries. See Figure 1. This survey collected diverse opinions on BPCs regarding (i) the necessity of legalization of the certification of competency of skilled practitioners of BIM, (ii) granting BIM practice certifications as a supplementation tool for the construction industry, (iii) the conditions for BIM certificate issuance and (iv) other opinions on BPCs. After evaluating 180 completed responses, selected available respondents were contacted for further discussion. All the answers were tested and ranked by the Friedman test and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Subsequently, an in-depth expert interview was again used to validate the research results. From these results, a framework for issuing BIM professional certificates was proposed. The research process is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research method framework.

3. Review of BIM Practitioner Certifications (BPCs) and Competencies

Engineers are working more across national borders. Therefore, it is increasingly vital to agree on international professional regulations, standards and recognitions. The global need for the mobility of engineers requires the accreditation of engineering educational programs and professional competence. The World Federation of Engineering Organizations (WFEO), the international organization for the engineering profession, was founded in 1968 under UNESCO’s auspices. National engineering institutions from one hundred nations with more than thirty million engineers joined WFEO [5]. ASEAN is an active market and production base, a highly competitive region with equitable economic development and is fully integrated into the global economy. To promote commerce, investment and labor exchange, ASEAN countries are trying to build equivalence in technical regulations, standards harmonization, alignment with international standards and MRAs [12].

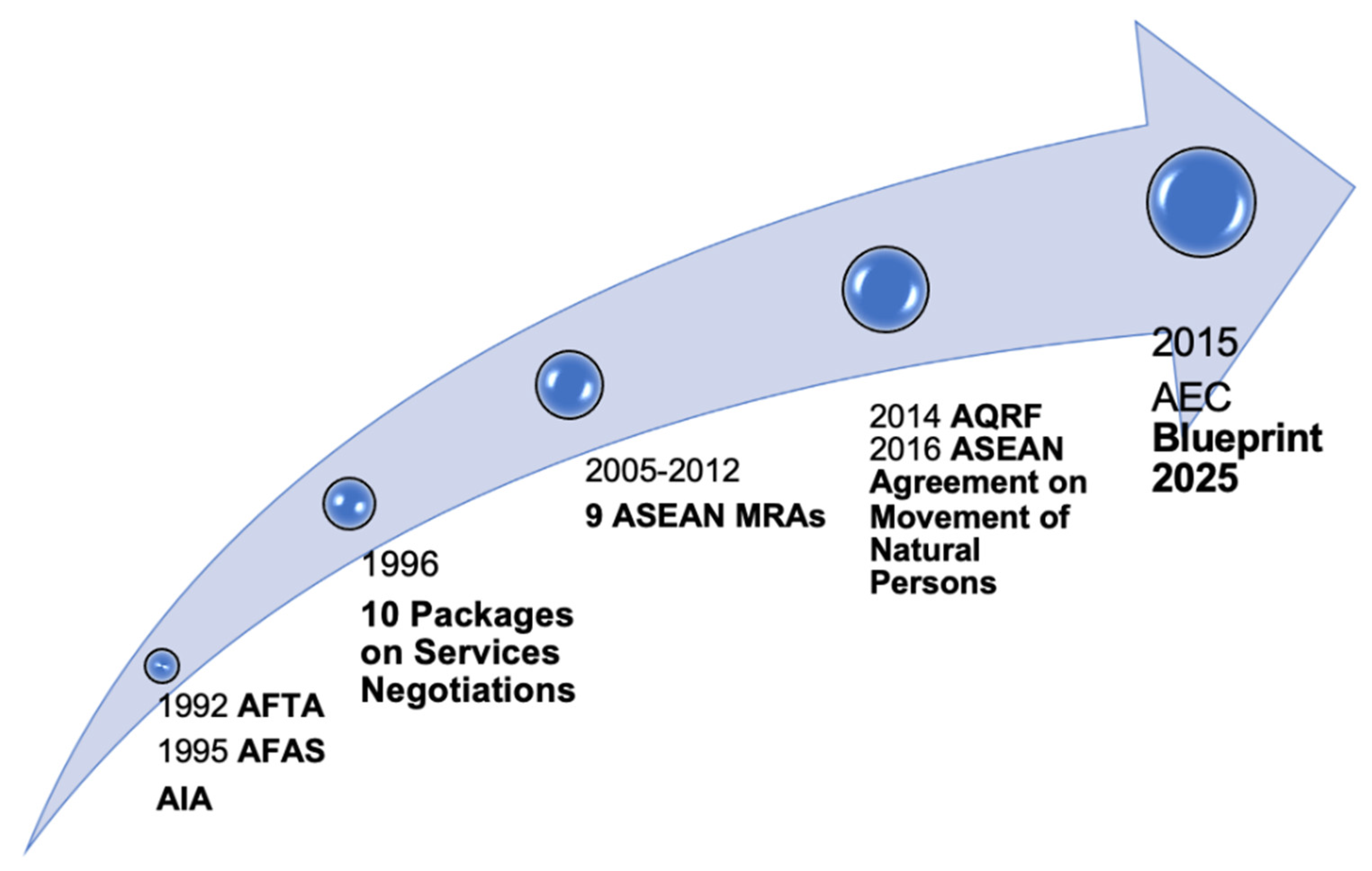

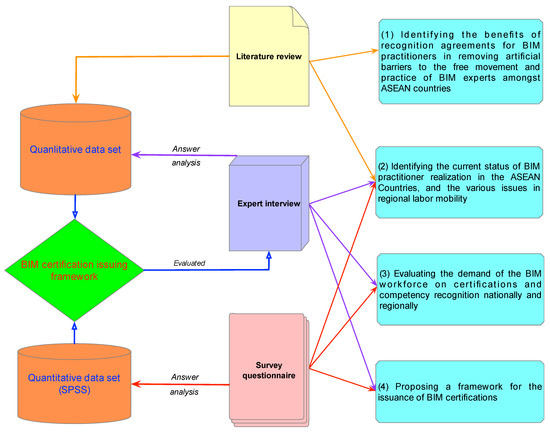

In 1992, the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) was established as a trade bloc by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations for supporting local trade and manufacturing in all ASEAN countries. To build the ASEAN community, MRAs were signed by nine ASEAN member countries in 2005. The MRAs are agreements among ASEAN member countries that provide mutual recognition of the results of conformity assessments conducted in one member state by authorities in the other ASEAN member states. As of June 2019, there were 3733 engineers on the ASEAN Chartered Professional Engineers Register and 545 architects registered as ASEAN Architects [12]. In 2007, the ASEAN member states’ leaders created their vision for a realization of the ASEAN economic community. The first pillar of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) Blueprint 2015 is “a single market and production base”, listing a variety of free-flow policies, including the free flow of skilled labor [2]. In 2016, the ASEAN Agreement on the Movement of Natural Persons was passed, and ASEAN planned the AEC Blueprint 2025. Vision 2020 called for a “free flow of skilled labors and professionals in the region”, including the creation of “ASEAN lanes” at ports of entry to facilitate travel by citizens of member states [5]. The AEC Blueprint 2025 moves the member states towards being more highly integrated and cohesive, competitive, innovative and dynamic, with enhanced connectivity and sectoral cooperation and a more resilient, inclusive and people-oriented, people-centered community integrated with the global economy [3]. The governments in the region acknowledge the importance of mutual recognition and professional mobility [12]. The expectation of skilled labor recognition agreements of BIM experts in ASEAN has also spread more widely. An overview of selected ASEAN agreements related to MRAs is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overview of selected Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) agreements related to Mutual Recognition Arrangements (MRAs).

The term “competency” refers to an individual’s ability to perform a specific task or deliver a measurable outcome. The competency of an individual is the fundamental basis of an organization’s capability [1]. Riyan Arthur et al. proposed that the required competency of construction workers is high, and the certification of competency must be improved through measurement and evaluation [17]. Succar et al. developed the model of individual competency from Benner’s study, which includes (0) none, (1) basic, (2) intermediate, (3) advanced and (4) expert [18].

Individual competency includes five distinct levels [4,18]. In this study, Level 3 (advanced), which denotes significant conceptual knowledge and practical experience in performing a competency to a consistently high standard, and Level 4 (expert), which denotes extensive knowledge, refined skills and prolonged experience in performing a defined competency at the highest standard, were both considered for granting BPCs.

ASEAN member countries’ regulations on professional engineer licenses/certifications are required for individuals conducting construction activities. For instance, in Vietnam, according to the Vietnam Construction Law 2014, individuals conducting construction activities must have diplomas and training certificates relevant to their construction jobs granted by lawful training institutions [19]. The construction practicing certificate shall be issued to Vietnamese citizens, overseas Vietnamese citizens or foreigners who legally carry out construction activities in Vietnam for them to hold certain positions or run their own construction business as prescribed in Clause 3, Article 148 of the Law on Construction 2014 [19]. In Singapore, professional engineer licenses will be provided to candidates if they have passed the Practice of Professional Engineering Examination or an oral examination [20].

ASEAN member countries have not gotten regulations or intentions to implement a BIM certification system for quality assurance of BIM-enhanced construction activities. Recently, licenses/certifications for BIM human resources have been granted by individual private institutes instead of through systematic regulations or general standards. For example, in Singapore, academic centers that provide BIM courses give learners who meet all the requirements a BIM certificate. Another academy named Building and Construction Authority (BCA) has BIM courses and a corresponding BIM certificate as a Specialist Diploma in Building Information Modeling, with a certification course in BIM, BIM management and BIM planning (building developers and facility managers) [21]. In another center named Singapore Polytechnic, different kinds of BIM certificate programs are available, such as a Specialist Diploma in BIM, BIM Basics, BIM Intermediate and BIM Advanced (combined architecture track and structure track) [22]. In Thailand, the Zigurat Global Institute of Technology has some BIM programs, such as a Master’s in Global BIM Management. Silicon Valley is a company that provides BIM courses, such as in BIM drafting and drawing services, BIM construction documentation, conflict detection, parametric family creation, 3D visualization and virtual building projects [23]. In Myanmar, another Silicon Valley location supplies BIM courses, BIM diplomas, etc.

The intention of developing BIM roles and responsibilities is to enhance the competencies of the disciplines in an integrated manner. The three leading roles of BIM practitioners are modeling (modeler), management (manager) and coordination (coordinator). Succar et al., in 2013, identified a set of BIM-specific roles (including a BIM manager, model manager and lead BIM coordinator) [4]. The UK AEC BIM Protocol also records the responsibilities of BIM managers, BIM coordinators and BIM modelers [24]. Based on the British Construction Industry Council (CIC) guidelines, the responsibilities of the BIM manager, the BIM coordinator and the BIM modeler are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Responsibilities of the building information modeling (BIM) manager, BIM coordinator and BIM modeler (source: [25]).

4. Expert Interviews

A significant amount of information on BIM human resource recognition was gathered from experienced BIM experts from different ASEAN member countries. The interviews were conducted to collect perspectives from BIM experts regarding their BIM knowledge via BIM publications, their working position and BIM research experience. In particular, the criteria for the selected experts were as follows:

- (i)

- at least five years of experience working in the construction sector,

- (ii)

- at least three years of experience with BIM,

- (iii)

- having BIM-related publications or at least one BIM project and

- (iv)

- working positions and working areas relevant to the ASEAN economic community.

Based on these criteria, five experts were approached in BIM-related international conferences, and another eleven experts were selected from those who work in ASEAN or national organizations. As a result, sixteen experts participated in individual in-depth interviews, conducted either face-to-face or via telephone (Table 2).

Table 2.

Basic details of the sixteen selected experts.

The interview aimed to explore the perspectives and experiences of researchers and experts who have experience in engineering practice management among ASEAN member countries and in the construction industry in particular about the existing problems, challenges and proposed directions for recognizing BIM practice certifications to create favorable conditions for ASEAN engineer mobilization. The interview questions focused on whether each ASEAN country has regulations or intentions to apply a type of BIM practice certification for management of the quality of construction activities and the necessity of BPCs and BIM individual competencies. The interviewees were asked to evaluate the framework for issuing BPCs suggested in this research as well. Interviewees were chosen using the purposive sampling technique. Saunders et al. explained that this technique enables researchers to use their judgment to select cases that will help answer research questions [26]. Table 2 shows the basic details and backgrounds of the experts.

According to the interviewees, BPCs not only bring benefits to the individual, but they also help the contractor in enhancing the strength of the contract profile in the bidding process. Besides, a BPC is a criterion for evaluating the bidding documents for construction projects involving BIM. The interviewees agreed that BPCs should be classified following the three main roles of BIM human resources, as mentioned above. From Expert 4, “BIM is the future of the construction industry”, and “critical regulations on BPCs enacted in ASEAN countries will set the fundamentals for regionalization and internationalization of BIM experts certifications recognition”. From Expert 14, “BPCs legalization is a way to verify the project team’s capability or provider BIM serviceability to deliver a BIM project.”

5. Survey Questionnaire

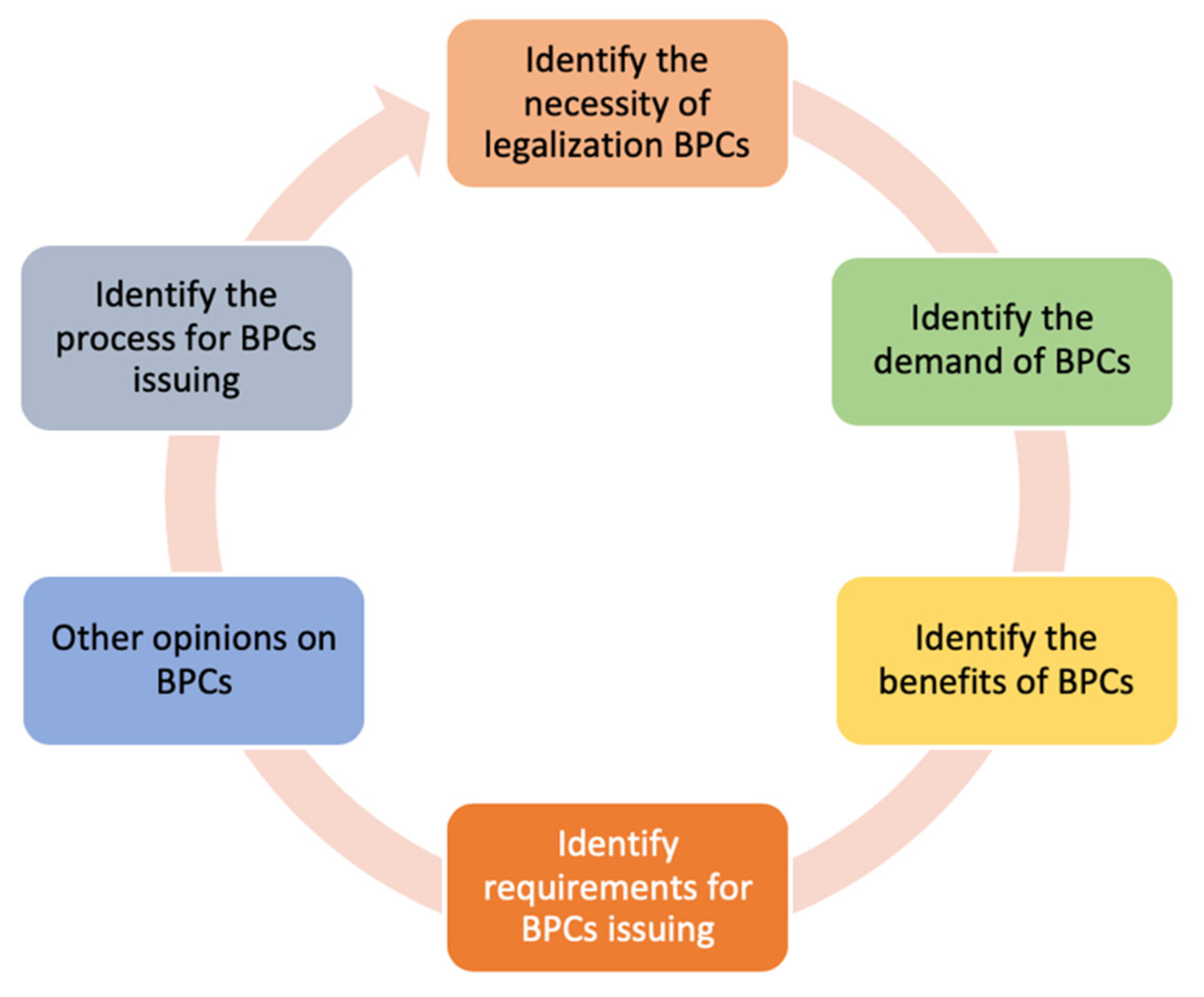

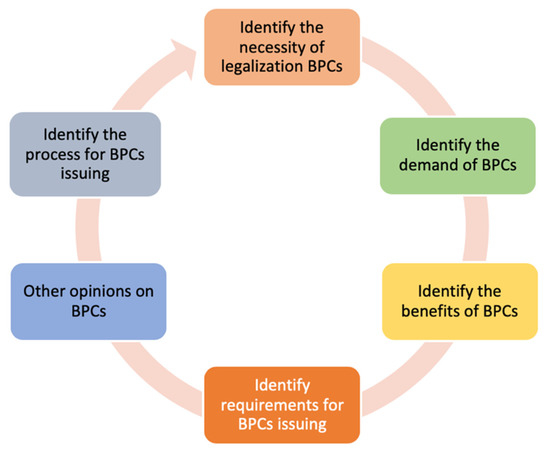

Qualitative and quantitative approaches were used to develop a comprehensive perspective on BPCs regarding stakeholders working in the construction sector in ASEAN member countries. Thirty-five survey questions were developed with information attained from the interviews and literature review. This online survey was then sent to possible participants in the ASEAN construction industry, with 180 complete answers collected in return. The survey aimed to explore the perspectives and experiences of respondents about the BIM practice certification demand as well as the proposed directions to recognize the capacity of BIM practice certifications to create favorable conditions for ASEAN engineer mobilization (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Objectives of the questionnaire survey.

The goals of the survey are to answer the following key questions:

- (1)

- Is the legalization of the certification of competency of skilled workers in BIM necessary in practice?

- (2)

- What are the benefits of legalizing and recognizing BPCs?

- (3)

- How about the process of issuing BIM practice certifications?

- (4)

- What are the requirements for issuing BIM certificates?

- (5)

- Do participants have other opinions on BPCs?

The questionnaire contained five main sections:

- (i)

- the extraction of the necessary information on the respondents,

- (ii)

- identifying the respondents’ perspectives on the necessity of legalization of BIM practitioner certification,

- (iii)

- the benefits of legalizing BIM practice certification,

- (iv)

- the process for issuing BIM practice certification and

- (v)

- open questions for respondents’ suggestions related to requirements for issuing BIM certificates.

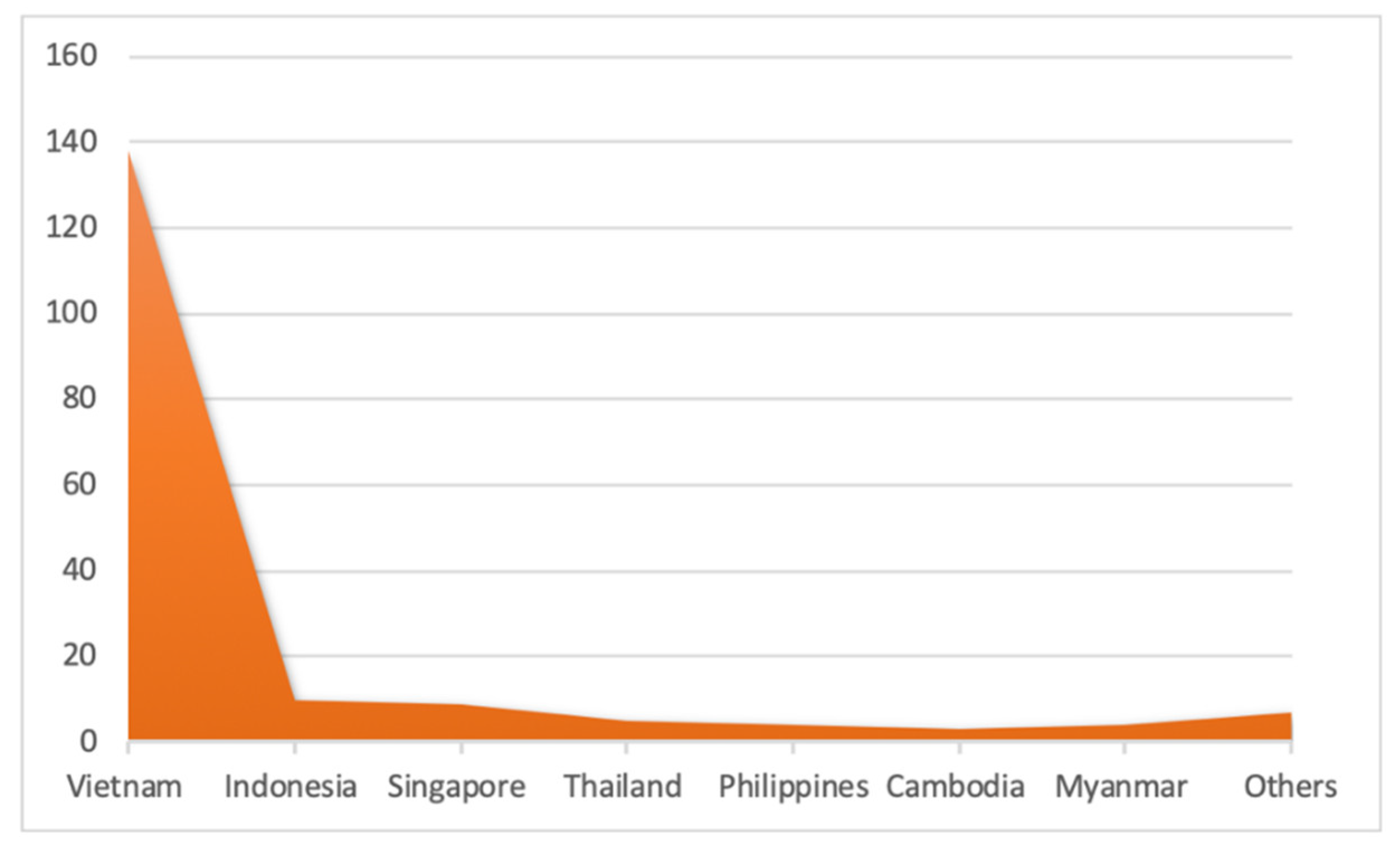

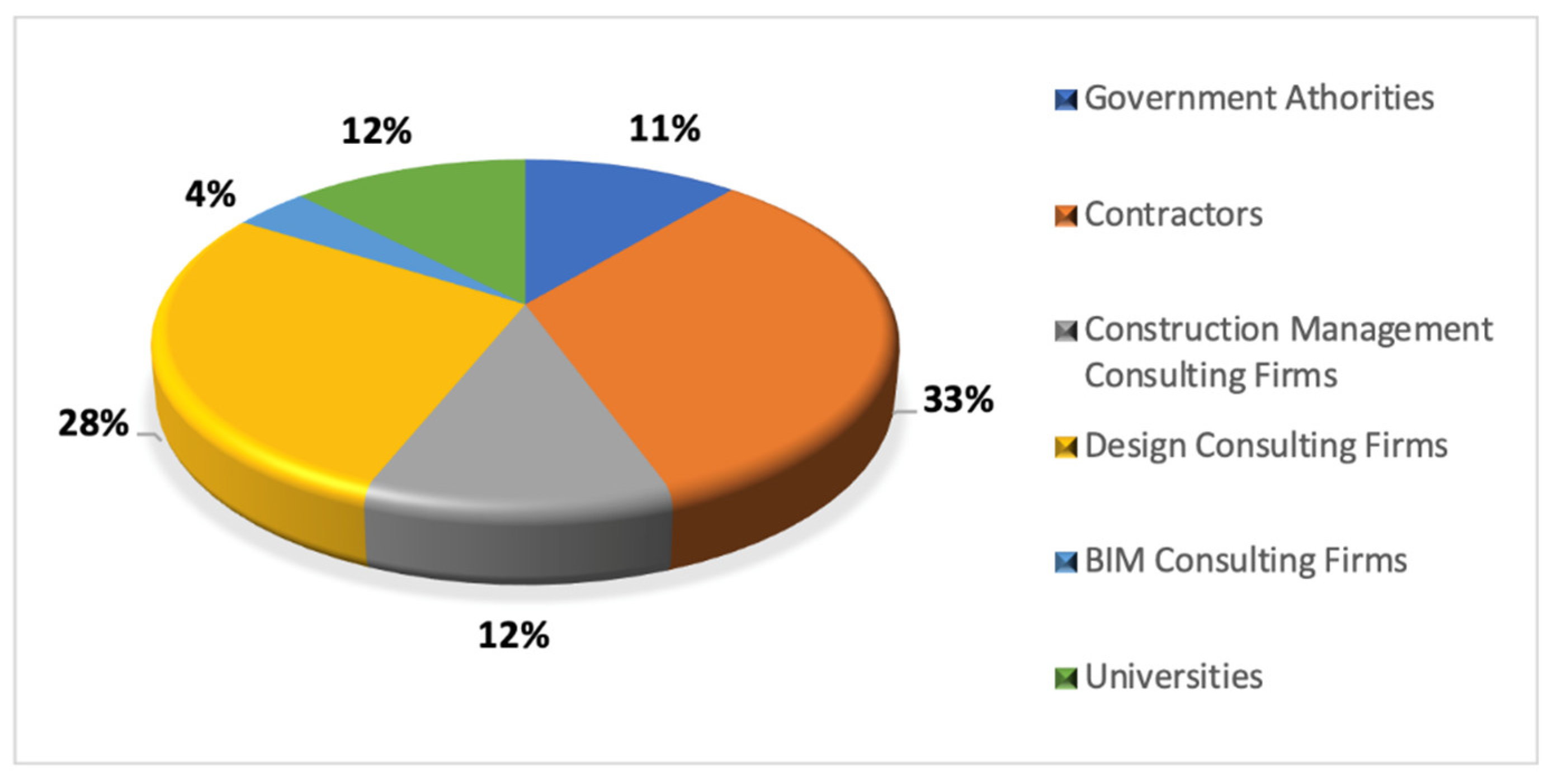

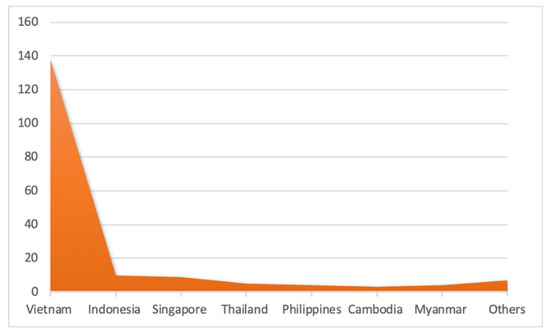

In Section (ii)–(iv), the respondents rated the answers using a five-point Likert scale: strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neutral (3), agree (4) and strongly agree (5). The questionnaires were sent to workers in the construction sector in ASEAN member countries. A total of 180 respondents completed the survey, including government authorities, owners, contractors, project managers, supervision consultants, BIM managers, BIM coordinators, BIM modelers, architects and engineers who work for public organizations, nongovernmental organizations, BIM consulting firms, construction management consulting firms, design consulting firms and universities from seven countries: Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines, Cambodia and Myanmar. Figure 4 illustrates the allocation of respondents according to the nation of work.

Figure 4.

Nations in which the respondents are working.

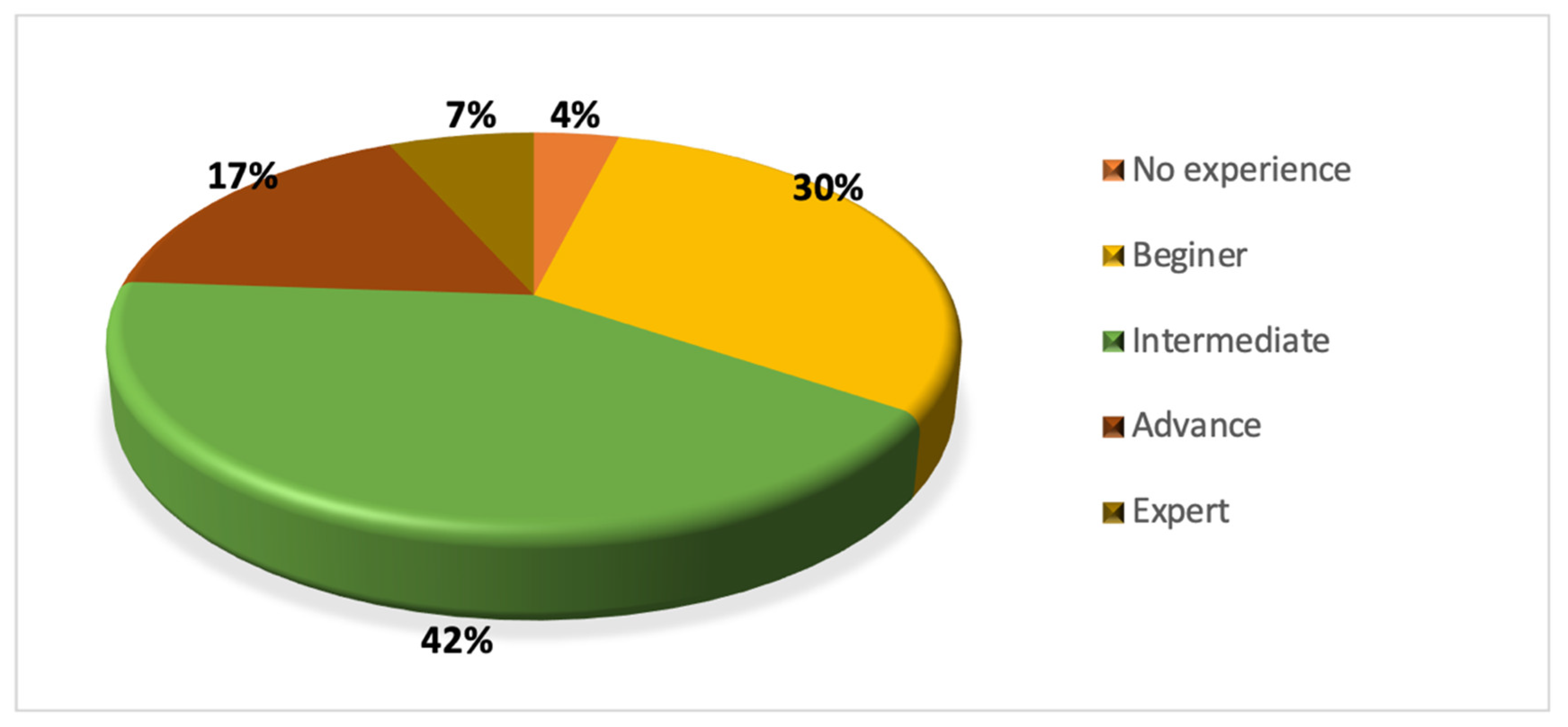

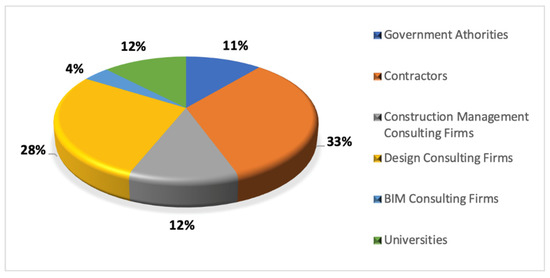

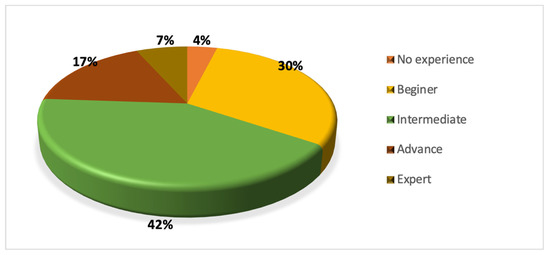

Figure 5 and Figure 6 illustrate the occupations and years of experience of respondents within the construction sector, respectively. The survey collected 180 responses from government authorities, contractors, construction management consulting firms, design consulting firms, BIM consulting firms and universities (Figure 5). Among them, there were 118 (~66%) respondents that had intermediate and above BIM experience, 31 respondents were advanced in BIM and 12 respondents were experts (Figure 6). Additionally, more than half of the respondents noted that they often worked with BIM in their projects. The answers received were evaluated by the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), with the output illustrated in Table 3 and Table 4: Asymp. Sig. p = 0.03. From these results and the respondents’ background information, their consistent answers indicate that the survey results are reliable.

Figure 5.

Occupations of the survey respondents.

Figure 6.

BIM experience of the survey respondents.

Table 3.

Benefits of BIM Practitioner Certifications.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of BIM Practitioner Certifications (BPCs)’ benefits.

According to the survey results, 91.67% of respondents required BIM certification and competency recognition in their nation and region and found it necessary to legalize BPCs. Most respondents agreed that BPCs bring a number of benefits (96% agreed and absolutely agreed) and BPCs should be legalized nationally and regionally. Those benefits are illustrated in Table 3.

The Friedman test was performed to see the most significant benefit that BPCs bring to BIM human resources as well as to employers. The Friedman test is known as a nonparametric alternative to one-way ANOVA with repeated measures, able to compare more than two dependent samples [27]. To compute the rank value of BPCs’ benefits (Fr), a table of data collected from the survey results was created. Then, the values for each benefit of BPCs were placed in columns next to the appropriate subjects, followed by the rank of the values for each subject across each condition. As there were ties (the collected data values were repeated) from the BPCs’ benefits, Equation (1) was used to determine the Friedman test statistic F [27]:

In Equation (1), n (180) is the number of answer forms received, k (12) is the number of benefits of BPCs, Ri is the sum of the ranks from column i and rij is the rank corresponding to subject j in column i. is the ties correction, calculated by Equation (2):

The test results suggested that there was no significant difference between all the identified BPCs (Table 3). Additionally, further analysis was conducted to observe if there were any significant differences when considering different groups of each pair of benefits. The results are shown in Table 4.

From the Friedman test results, the associated low significance level (p = 0.03) indicates that it was appropriate to use factor analysis. The sum of the ranks with positive differences was then computed. Based on the results from the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and the Friedman test results, the ranks with positive differences were 7.05, 6.78, 6.71, 6.68, 6.65, 6.56, 6.55, 6.43, 6.24, 6.16, 6.16, 6.11 and 6.08, respectively.

A total of twelve variables were related. To compare two related samples, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used, and two among the eleven samples were selected for analysis and comparison. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test is frequently used for the nonparametric testing of paired data based on independent units of analysis [28]. This test was performed to evaluate the tenability of the null hypothesis that two samples arose from the same population. The Friedman test was also used as a nonparametric method for repeated measures on three trials. The test came out statistically significant (p = 0.03), providing evidence that the samples were not drawn from the same population. Follow-up Wilcoxon signed-rank tests confirmed that pairwise differences existed between all trials [29]. The output is shown in Table 4. The correlation matrix is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Variable correlation (test statistic).

The analysis of BPCs’ benefits was done in two steps: (1) basic statistics (to determine the factors of primary concern among a list of twelve variables) and (2) factor analysis (to present a list of twelve variables in each pair of variables). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test (N = 180, p = 0.03 < 0.05) indicated that the percentage of successful interventions was significantly different. In contrast, if p > 0.05, then the percentage of successful interventions would not be significantly different [27]. In Table 5, the orange-colored output shows the correlation coefficients among the twelve variables. In particular, this table shows that all pairs had a low correlation, and the Friedman test output is reliable. Among the variables, the greatest benefit of BPCs was in aiding BIM practitioners to have a recognized professional standing, nationally and internationally (C10), followed by bringing BIM practitioners more job opportunities (C2).

A further association was needed for which kind of BPCs should be provided since there are varying BIM roles in a construction project; i.e., BPCs for BIM practitioners can be classified according to three main jobs of BIM employees: management (manager), coordination (coordinator) and modeling (modeler). It is possible to divide BIM employees according to construction expertise in either surveying, design, construction or operation. This raises the question of whether BPCs should be integrated with existing engineering practice certifications or whether BIM practice certifications should be separate. To answer this question from the survey data collected, the Friedman test was performed again. The output is illustrated in Table 6: Asymp. Sig. p = 0.000. This result indicates that the survey results are reliable. Equations (1) and (2) were used to calculate the mean rank, with n = 180 and k = 3.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics on the methods for BPC.

The interviews with the experts and the survey results had the same output. Interviewees agreed with certified BIM human resources following the three main jobs of BIM employees. The survey of 180 respondents processed by SPSS (N = 180; Asymp. Sig. p = 0.000) with the Friedman test found that granting a BPC for the three main jobs of BIM employees had a mean rank of 5.20, and granting a BPC that is integrated with existing practice certifications in the respondents’ country or granting a BPC generally for people who are working on BIM both had a mean rank of 4.33. In particular, BPCs should be granted as a supplementary tool for the construction industry according to the main jobs of BIM employees, the BIM manager, BIM modeler and BIM coordinator, as mentioned in the UK AEC BIM Protocol [24] and described in Table 1.

All of the respondents agreed that ASEAN countries had signed mutual recognition agreements on technical advisory services and an engineer who acts legally in other countries must register. “It’s necessary for extra this kind of agreement for BIM practitioner recognition”, a respondent shared.

6. Framework for Issuing BIM Practitioner Certifications

In this section, the requirements for three types of BPCs are presented. A framework for the issuance of BIM certifications was proposed and evaluated by experts. This framework was created depending on (i) existing ASEAN regional agreements, (ii) current regulations of ASEAN member countries, (iii) the questionnaire survey and (iv) expert interviews. The framework incorporated suggestions and opinions from the experts.

6.1. BIM Practitioner Certificate Requirements

There is a global need for the mobility of engineers and international agreements to serve as a platform for promoting technology exchange and accreditation of engineering education programs and professional competency [12]. Building a systematic requirement for BPCs could help address the widening skills gap in BIM in the ASEAN region to provide a better allocation of labor. This then also provides an explicit mechanism for capacity building and the training of BIM professionals.

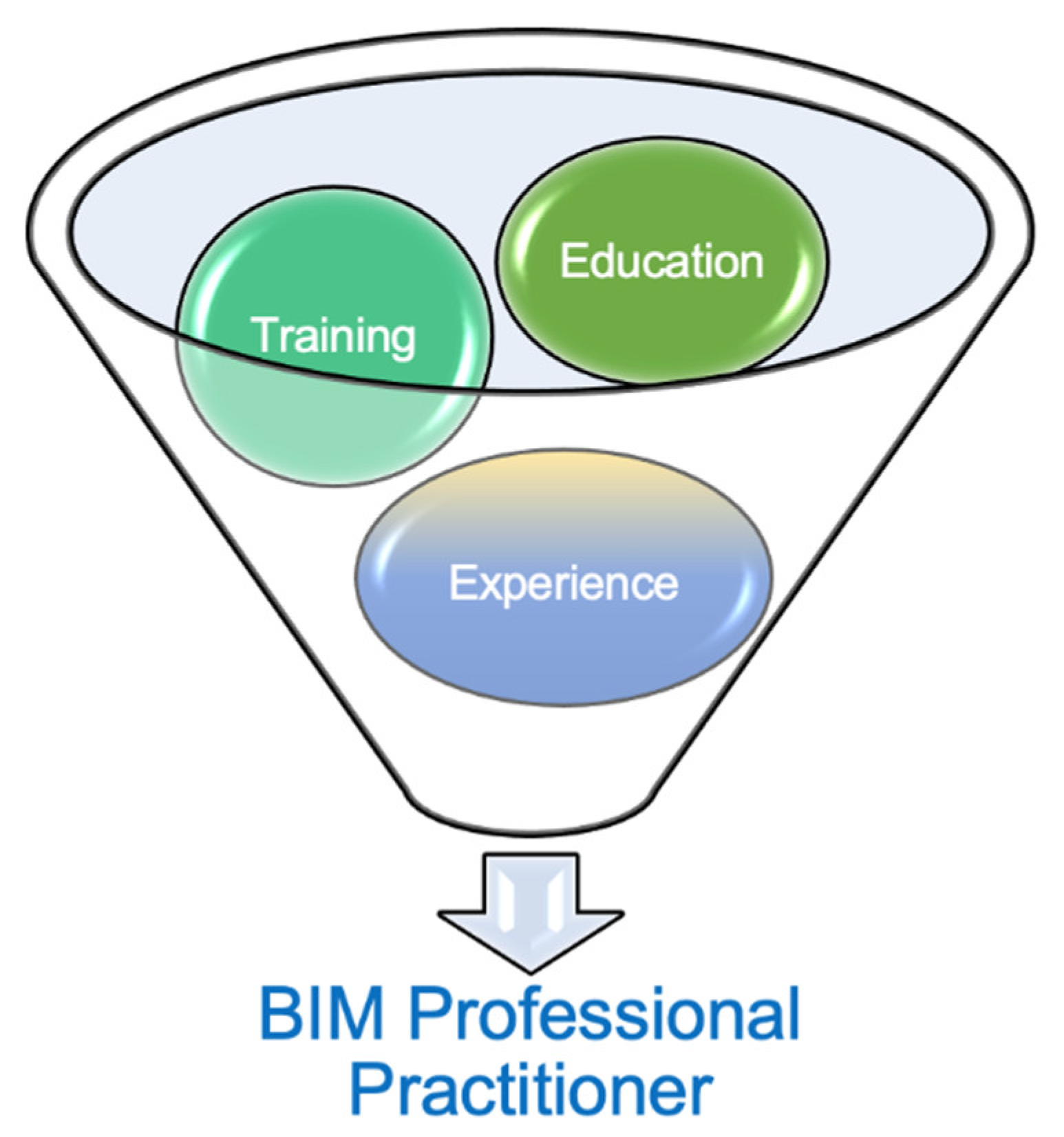

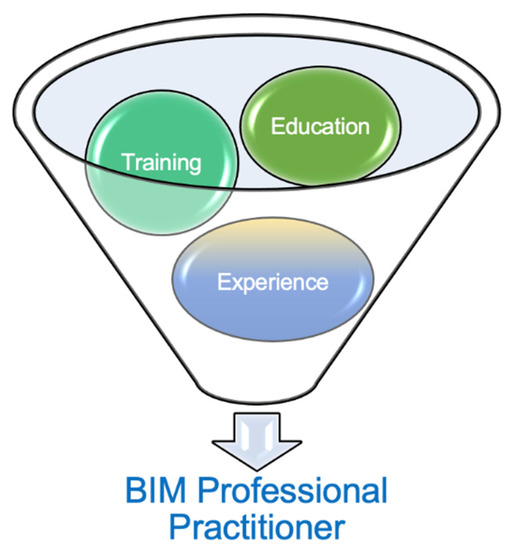

In this section, the raw data on the requirements for three types of BPCs are described in Table 7 by integrating Table 1 and the literature review. From these results, a candidate needs to have the correct education degree(s), a training program certificate(s) and several years of experience in BIM for each kind of certificate, as shown in Figure 7.

Table 7.

BIM competency requirements.

Figure 7.

Candidate requirements for BIM Practitioner Certification.

Following the certification, as an ASEAN Chartered Professional Engineer from the ASEAN Chartered Professional Engineer Coordinating Committee, an applicant must have education, training and experience (Figure 7). For degrees with appropriate majors and the years of experience in a BPC application, there are significant issues that need to be addressed through more in-depth discussion and examination by empirical research.

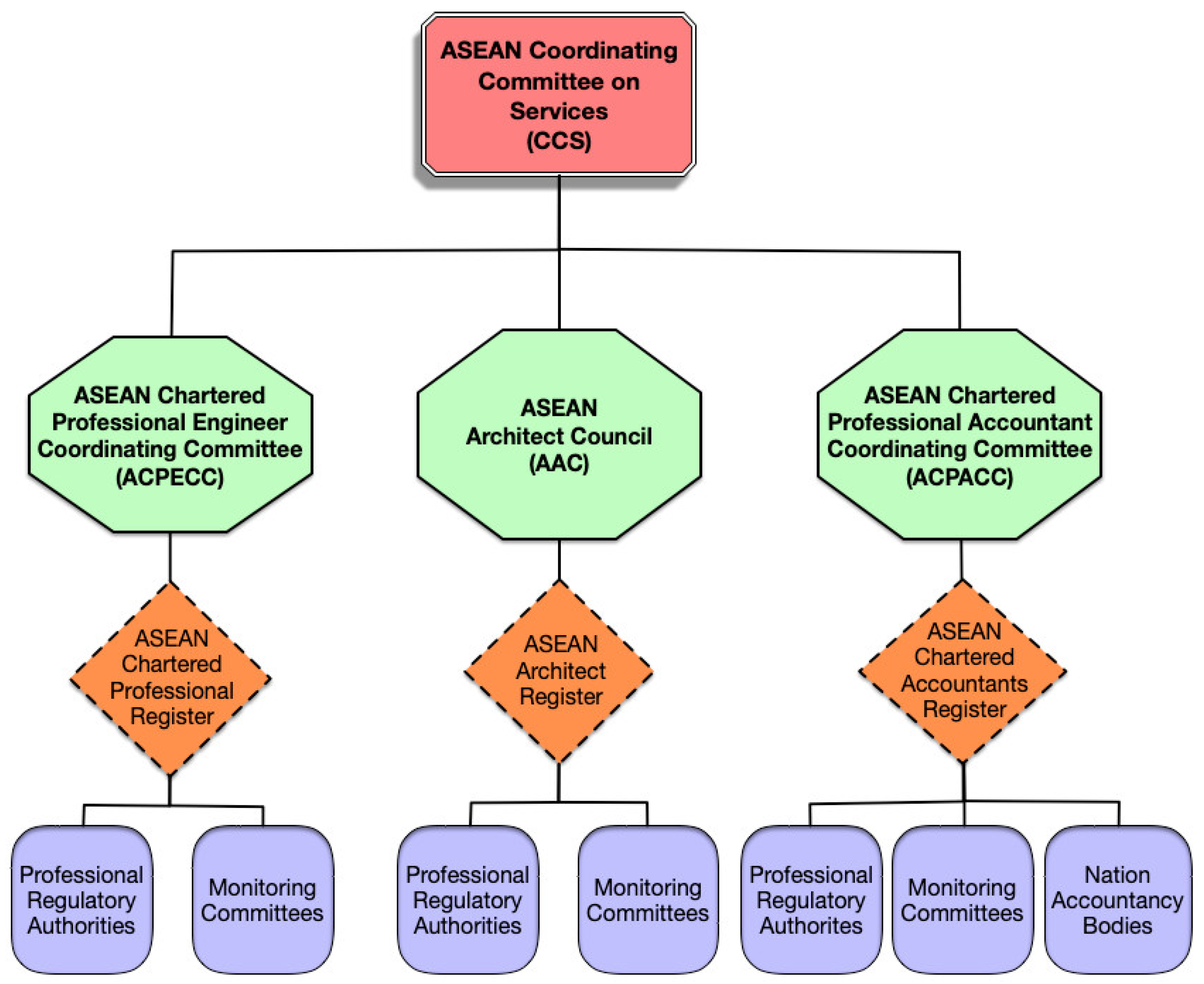

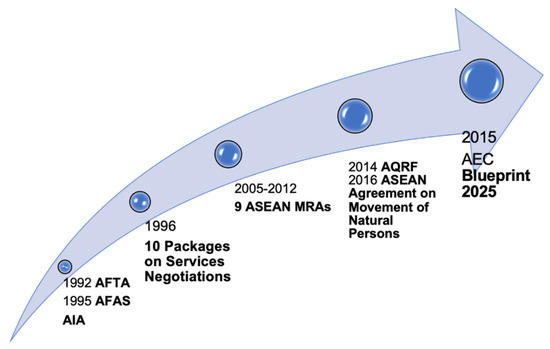

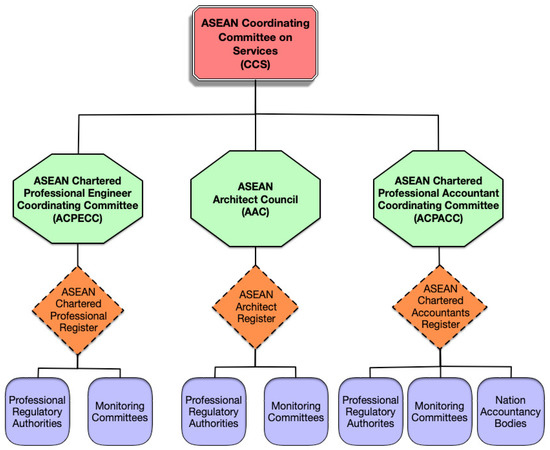

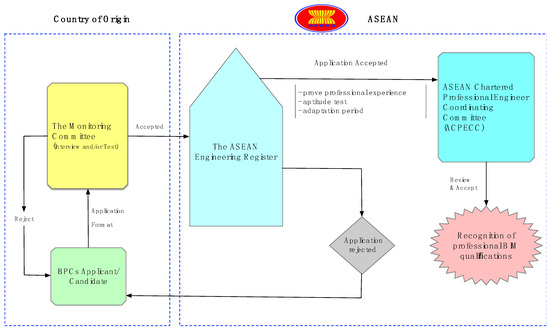

6.2. Issuance of BIM Practitioner Certificates

Progress in granting BPCs cannot be made without first addressing the restrictive domestic regulations that facilitate mobility. Countries in the region may consider testing ways to legalize BPCs. This then can be extended if proven effective and integrated into the current regional agreement as MRAs. Through the mechanisms available within ASEAN as MRAs, issuing BPCs can follow the current status of agreements in the region. For instance, according to ASEAN member countries’ current agreements, a candidate who has completed the process outlined in the MRA will enter into the registry and earn a special designation as an ASEAN Architect, an ASEAN Chartered Professional Accountant or an ASEAN Chartered Professional Engineer. The coordinating committees for three occupations are the ASEAN Architect Council (AAC), the ASEAN Chartered Professional Accountant Coordinating Committee (ACPACC) and the ASEAN Chartered Professional Engineer Coordinating Committee (ACPECC). The three committees are in charge of conferring the special ASEAN-level professional titles. Figure 8 below illustrates the implementation of MRAs on accounting, architecture and engineering services [3,31,32].

Figure 8.

MRAs on accounting, architecture and engineering services (drawn by the authors based on the integrated knowledge from [3,31,32]).

The experts interviewed and the questionnaire survey indicated that ASEAN countries had signed mutual recognition agreements on technical advisory services and an engineer who acts legally in other countries must register. It is necessary for additional agreements for BIM practitioner recognition. Current regulations of ASEAN member countries are appropriate for MRAs. Since there are available registration requirements as an ACPE, ASEAN governments and stakeholders can learn from these requirements by enacting domestic regulations on BPCs. To meet the demand for BPC recognition regionally and internationally, there are necessary regulatory and legislative changes. Integrating BPCs into current MRAs can lead to a regulatory regime that imposes requirements on the national legal system and cross-border agreements. Each government needs to enact the necessary regulations for ensuring the availability of technical infrastructure to assess conformance to standards, which could be generated through the exchange of information and frequent working contacts with other countries in the region since governments play an important role in leading the process of BIM implementation and certification [14]. Subsequently, a code of practice for BPC areas could be established as applicable to ASEAN countries. As a result, BIM practitioners can apply for the BPCs via the Monitoring Committee in their country of origin. A BIM practitioner who meets the listed qualifications can apply to be an ACPE in BIM if they meet all requirements for each kind of certificate (Table 7) and agree to be bound by the code of professional conduct and ethics. The proposed framework for the issuance of BIM practitioner certifications was evaluated as an appropriate suggestion by the experts (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

A proposed framework for the issuance of BIM certifications.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

This study shows that there is significant demand for the recognition of BIM practitioners, and recognition agreements for BIM practitioners would help with the implementation of BIM. This leads to the necessity of recognizing experienced engineers via registration or licensing, which is a means to remove artificial barriers to the free movement and practice of BIM human resources amongst ASEAN countries. In the absence of proper BIM Practitioner Certification systems, various related issues in regional labor mobility may come up. National regulatory and legislative changes and supplementary regional agreements are necessary to meet this demand. Through these changes, experts from neighboring countries can come to work and help push the construction industry in some ASEAN countries that lack BIM experts. A BIM practitioner who possesses the qualifications, complies with the imposed conditions and satisfies the assessment statement should be placed on the ASEAN Chartered Professional Engineers (ACPE) Register and conferred the title of ACPE in BIM. BPCs should be listed on the ASEAN Chartered Professional Engineers Register to ensure that BIM practitioners have opportunities to have their professional standing recognized within the ASEAN region, thereby contributing to the globalization of professional engineering services. To support this, each ASEAN member country’s authorities, as well as the professional regulatory authority in the ASEAN Mutual Recognition Arrangement on Engineering Services, need to enact the relevant regulations on BIM.

From the perspective of an owner choosing tenders on projects involving BIM, it was found that proving the BIM capability of both organizations and individuals is an important criterion. National regulatory and legislative changes and supplementary regional agreements are necessary to fulfill this demand. The integration of BPCs into current MRAs leads to a regulatory regime that imposes requirements on the national legal system and cross-border agreements. Each government needs to enact the necessary regulations for ensuring that its technical infrastructure can assess conformance to standards, which could be generated through the exchange of information and frequent working contact with other MRA partners. Alternatively, these could be generated through attestation by a higher-level system, such as an international organization, using objective and recognized standards. As a result, this study proposed a framework for the issuance of BIM practitioner certifications (Figure 9). This study shows that BPCs should be granted according to three main jobs of BIM employees: modelers, managers and coordinators.

Certain limitations must be considered due to the restriction of the diversity of interviewees and survey respondents. The three types of BPCs need to be discussed and researched further empirically. This new idea leads to a challenge on how to overcome restrictive domestic regulations. Future research is necessary to examine the potential solutions for certifying and recognizing BIM practitioners and their competency.

8. Future Research

Future research can increase the sample size of the questionnaire and later, the respondents in ASEAN countries. An in-depth interview with experts is a necessity to discuss further the issues mentioned above and findings as well as examine the potential solutions for certifying and recognizing BIM practitioners and their competency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-N.D., T.-Q.N. and P.-H.C.; methodology, P.-H.C. and T.-N.D.; investigation, T.-N.D. and T.-Q.N.; writing—original draft preparation and data analysis, T.-N.D.; writing—reviewing and editing, P.-H.C., T.-N.D. and T.-Q.N.; visualization, P.-H.C. and T.-N.D.; supervision, P.-H.C.; funding acquisition, T.-Q.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National University of Civil Engineering, Hanoi, Vietnam under grant number 223-2018/KHXD-TĐ.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the National University of Civil Engineering, Hanoi, Vietnam for supporting this research under grant number 223-2018/KHXD-TĐ.

Conflicts of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| No. | Abbreviations | Definitions |

| 1 | ASEAN | Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

| 2 | BPCs | BIM Practitioner Certifications |

| 3 | MRAs | ASEAN Mutual Recognition Arrangements |

| 4 | ACPE | ASEAN Chartered Professional Engineer |

| 5 | AFEO | ASEAN Federation of Engineering Organizations |

| 6 | ACPECC | ASEAN Chartered Professional Engineer Coordinating Committee |

| 7 | APEC | Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation |

| 8 | WFEO | World Federation of Engineering Organizations |

| 9 | AFTA | ASEAN Free Trade Area |

| 10 | CIC | British Construction Industry Council |

| 11 | EPC | Engineering, Procurement and Construction |

| 12 | M&E | Mechanical and Electrical |

| 13 | AAC | ASEAN Architect Council |

| 14 | ACPACC | ASEAN Chartered Professional Accountant Coordinating Committee |

References

- Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). ASEAN Integration Report; ASEAN: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga, Y. Challenges of ASEAN MRAs on Professional Services. In ASEAN Law in the New Regional Economic Order, 1st ed.; Hsieh, P.L., Mercurio, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint 2025; ASEAN: Singapore, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Succar, B.; Sher, W.; Williams, A. An integrated approach to BIM competency assessment, acquisition and application. Autom. Constr. 2013, 35, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, P. Up-Dated Information Paper on Mobility Prepared for WFEO Standing Committee on Education in Engineering; CEIE: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman, C.M.; Teicholz, P.M.; Sacks, R.; Lee, G. BIM Handbook: A Guide to Building Information Modeling for Owners, Managers, Designers, Engineers and Contractors, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Poljanšek, M. Building Information Modelling (BIM) Standardization; JRC Joint Research Centre: Ispra, Italy, 2017; Volume 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.P.; Bragança, L.; Mateus, R. A Systematic Review of the Role of BIM in Building Sustainability Assessment Methods. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-U.; Hadadi, O.; Kim, H.; Kim, J. Development of A BIM-Based Maintenance Decision-Making Framework for the Optimization between Energy Efficiency and Investment Costs. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.P.; Freda, R.; Nguyen, T.H.D. Building Information Modelling Feasibility Study for Building Surveying. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhm, M.; Lee, G.; Jeon, B. An analysis of BIM jobs and competencies based on the use of terms in the industry. Autom. Constr. 2017, 81, 67–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, D.R.; Sugiyarto, G. The Long Road Ahead: Status Report on the Implementation of the ASEAN Mutual Recognition Arrangements on Professional Services; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thuy-Ninh, D.; Po-Han, C. The-Quan Nguyen Critical Success Factors and a Contractual Framework for Construction Projects Adopting Building Information Modeling in Vietnam. Int. J. Civil Eng. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.-N.; Nguyen, T.-Q.; Chen, P.-H. BIM Adoption in Construction Projects Funded with State-managed Capital in Vietnam: Legal Issues and Proposed Solutions. In Innovation for Sustainable Infrastructure. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiebat, M.; Ku, K. Industry’s Expectations of Construction School Graduates’ BIM Skills; Associated Schools of Construction: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Fargnoli, M.; Lombardi, M. Building Information Modelling (BIM) to Enhance Occupational Safety in Construction Activities: Research Trends Emerging from One Decade of Studies. Buildings 2020, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, R.D. A Need Assessment on Competency Certification of Construction Workers in Indonesia. KSS 2019, 3, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deakin University, Faculty of Education, Open Campus Program. In A Collection of Readings Related to Competency-Based Training; Deakin University: Geelong, VC, USA, 1994.

- The National Assembly. The Construction Law, No 50/2014/QH13, 2014; The National Assembly: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Singapore; Professional Engineer Act: Singapore, 1992. Available online: https://sso.agc.gov.sg (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- BCA Academy. Certification Course on BIM Management. 2020. Available online: https://www.bcaa.edu.sg/ (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Singapore Polytechnic Specialist Diploma in Building Information Modelling Management. Available online: https://www.sp.edu.sg/ (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Silicon Valley BIM Services. BIM Services 2020. Available online: https://www.siliconinfo.com/ (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Construction Industry Council bim-protocol-2nd-edition-2. In Building Information Modeling (BIM) Protocol, 2nd ed.; CIC: Hong Kong, China, 2018.

- AEC (UK). BIM Technology Protocol: Practical Implementation of BIM for the UK Architectural, Engineering and Construction (AEC) Industry. Available online: https://aecuk.wordpress.com/ (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Balina, S. Research Methods for Business Students, 7th ed.; Mark, N.K., Saunders, P.L., Thornhill, A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, W.; Corder, D.I. Foreman—Second Edition. Nonparametric Statistics: A Step-By-Step Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner, B.; Glynn, R.J.; Lee, M.-L.T. The Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test for Paired Comparisons of Clustered Data. Biometrics 2006, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, D.J. SPSS Data Analysis for Univariate, Bivariate and Multivariate Statistics; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- British Standards Institution. PAS 1192-2:2013: Specification for Information Management for the Capital/Delivery Phase of Construction Projects Using Building Information Modelling; British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ASEAN Consultative Committee for Standards & Quality. Guidelines for The Development of Mutual Recognition Arrangements; ASEAN Consultative Committee for Standards & Quality: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2018.

- Fukunaga, Y. Assessing the Progress of ASEAN MRAs on Professional Services; Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).