Traditional or Fast Foods, Which One Do You Choose? The Roles of Traditional Value, Modern Value, and Promotion Focus

Abstract

:1. Introduction

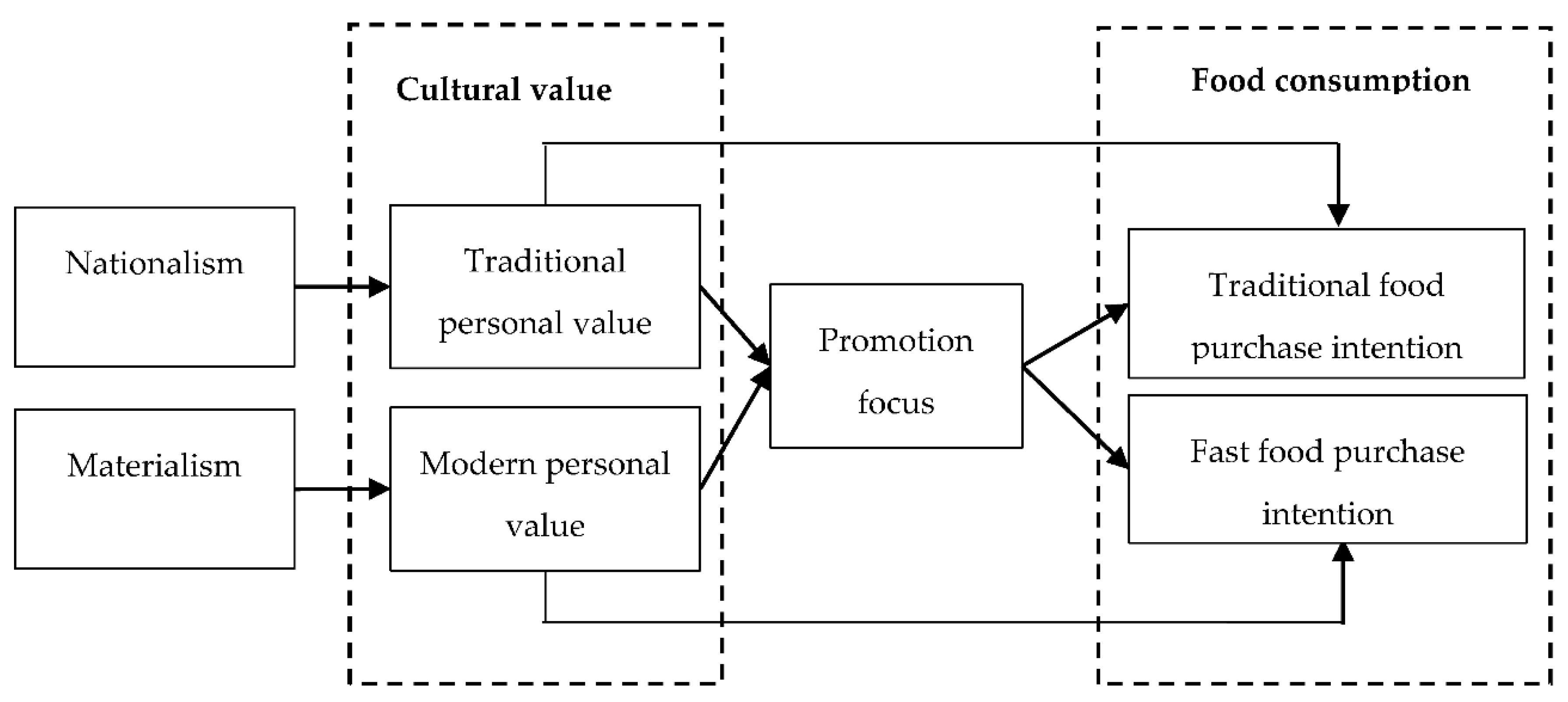

2. Literature and Hypotheses

2.1. National Cultural Value and Chinese Cultural Value

2.1.1. Nationalism and Traditional Personal Value

2.1.2. Materialism and Modern Personal Value

2.2. Cultural Value and Food Consumption

2.3. The Mediating Role of Promotion Focus

2.4. Comparing the Effects of Traditional Personal Value and Modern Personal Value on Food Consumption

3. Methods

3.1. Instrument and Measures

3.2. Data Collection Procedure

3.3. Ethics Approval

3.4. Analysis Methods

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.3. Common Method Bias

4.4. Testing the Direct Effect

4.5. Testing the Mediating Effect

4.6. Comparing the Effect of Traditional and Modern Personal Vaules

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alae-Carew, C.; Nicoleau, S.; Bird, F.A.; Hawkins, P.; Tuomisto, H.L.; Haines, A.; Dangour, A.D.; Scheelbeek, P.F. The impact of environmental changes on the yield and nutritional quality of fruits, nuts and seeds: A systematic review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 023002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banik, R.; Naher, S.; Pervez, S.; Hossain, M.M. Fast food consumption and obesity among urban college going adolescents in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. Obes. Med. 2020, 17, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, L.; Stubbs, B.; Firth, J.; Smith, L.; Haro, J.M.; Koyanagi, A. Fast food consumption and suicide attempts among adolescents aged 12–15 years from 32 countries. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 266, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado-Oliveira, M.C.; Nezlek, J.; Rodrigues, H.; Sant’Ana, A.S. Personality traits and food consumption: An overview of recent research. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2020, 33, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhen, L.; Wei, Y. Food consumption and its local dependence: A case study in the Xilin Gol Grassland, China. Environ. Dev. 2019, 34, 100470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.I.N.; Hou, L.L.; Hermann, W.; Huang, J.K.; Mu, Y.Y. The impact of migration on the food consumption and nutrition of left-behind family members: Evidence from a minority mountainous region of southwestern China. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 1780–1792. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.C.; Chang, C.T.; Chen, Y.H.; Huang, Y.S. The spell of cuteness in food consumption? It depends on food type and consumption motivation. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 65, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwah, S.; Dhir, A.; Sagar, M.; Gupta, B. Determinants of organic food consumption. A systematic literature review on motives and barriers. Appetite 2019, 143, 104402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, M.; O’Cass, A.; Otahal, P. A meta-analytic study of the factors driving the purchase of organic food. Appetite 2018, 125, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scalco, A.; Noventa, S.; Sartori, R.; Ceschi, A. Predicting organic food consumption: A meta-analytic structural equation model based on the theory of planned behavior. Appetite 2017, 112, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G. Food, eating behavior, and culture in Chinese society. J. Ethn. Foods 2015, 2, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenheck, R. Fast food consumption and increased caloric intake: A systematic review of a trajectory towards weight gain and obesity risk. Obes. Rev. 2008, 9, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, A.M.; Bezerra, I.W.; Pereira, G.S.; Torres, K.G.; Costa, R.M.; Oliveira, A.G. Relationships between Motivations for Food Choices and Consumption of Food Groups: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Survey in Manufacturing Workers in Brazil. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchet, R.; Willows, N.; Johnson, S.; Okanagan Nation Salmon Reintroduction Initiatives; Batal, M. Traditional Food, Health, and Diet Quality in Syilx Okanagan Adults in British Columbia, Canada. Nutrients 2020, 12, 927. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs, S. The Chinese Medicine Cookbook: Nourishing Recipes to Heal and Thrive; ALTHEA Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M.; Esmaeilzadeh, P.; Uz, I.; Tennant, V.M. The effects of national cultural values on individuals’ intention to participate in peer-to-peer sharing economy. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 97, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Organising for cultural diversity. Eur. Manag. J. 1989, 7, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Huang, S.S. Reconfiguring Chinese cultural values and their tourism implications. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y. A classification of Chinese culture. Cross Cult. Manag. 2000, 7, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.; Greenfield, P.M. Cultural evolution over the last 40 years in China: Using the Google Ngram Viewer to study implications of social and political change for cultural values. Int. J. Psychol. 2015, 50, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, H. Personal value vs. luxury value: What are Chinese luxury consumers shopping for when buying luxury fashion goods? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boobalan, K.; Nachimuthu, G.S. Organic consumerism: A comparison between India and the USA. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Ploeger, A. Explaining consumers’ intentions towards purchasing green food in Qingdao, China: The amendment and extension of the theory of planned behavior. Appetite 2019, 133, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thøgersen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, G. How stable is the value basis for organic food consumption in China? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Beyond pleasure and pain. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, E.T. Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Academic: San Diego, CA, USA, 1998; Volume 30, pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- China Industry Reports. Available online: www.Chinairr.org (accessed on 11 July 2020).

- Tan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, H. Healthy China 2030, a breakthrough for improving health. Glob. Health Promot. 2019, 26, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Xue, H.; Qu, W. A review of the growth of the fast food industry in China and its potential impact on obesity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.C. Food in Chinese Culture: Antropological and Historical Perspectives; Yale University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Lee, P.; Law, R. Impact of cultural values on technology acceptance and technology readiness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Ding, Z.; Li, X.; Sun, J.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, R.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W. How cultural values and anticipated guilt matter in Chinese residents’ intention of low carbon consuming behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 119069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Han, X.; Wen, H.; Ren, J.; Qi, L. Better dietary knowledge and socioeconomic status (ses), better body mass index? evidence from china—An unconditional quantile regression approach. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.W.; Peng, K. Culture and cause: American and Chinese attributions for social and physical events. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Huang, S.S.; Ying, T. Relationships between Chinese cultural values and tourist motivations: A study of Chinese tourists visiting Israel. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 14, 100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Yin, J. Linking Chinese cultural values and the adoption of electric vehicles: The mediating role of ethical evaluation. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 56, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.D. Nationalism: Theory, Ideology, History; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.D. Nationalism in the Twentieth Century; Australian National University Press: Canberra, Australia, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J. Modern Chinese Nationalism; Hunter College: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, S.S. The Widening Gulf: Asian Nationalism and American Policy; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney, J.B.R. China: Area, Administration and Nation-Building; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, C.R. Chinese Nationalism in the Global Era; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ojha, I.C. Chinese Foreign Policy in an Age of Transition: The Diplomacy of Cultural Despair; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Unger, J. Chinese Nationalism; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, J. Chinese nationalism. Aust. J. Chin. Aff. 1992, 27, 97–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. Cultural Nationalism in Contemporary China; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y. The Chinese path to individualization. Br. J. Sociol. 2010, 61, 489–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maercker, A.; Mohiyeddini, C.; Müller, M.; Xie, W.; Yang, Z.H.; Wang, J.; Müller, J. Traditional versus modern values, self-perceived interpersonal factors, and posttraumatic stress in Chinese and German crime victims. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2009, 82, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lu, L.; Kao, S.F. Traditional and modern characteristics across the generations: Similarities and discrepancies. J. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 142, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belk, R.W. Materialism: Trait aspects of living in the material world. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K. Materialism among children in urban China. In Proceedings of the American Academy of Advertising Asia Pacific Conference, Hong Kong, China, 12 December 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.T.; Yin, L.J.; Saito, M. Function of traditional foods and food culture in China. Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. JARQ 2004, 38, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, F.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, G.; Hu, X. Survey of acrylamide levels in Chinese foods. Food Addit. Contam. 2008, 1, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Tan, Y.; Wu, C.; Wang, S.; Yu, C.; Cao, W.; Gao, W.; Lv, J.; Li, L. City level of income and urbanization and availability of food stores and food service places in China. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148745. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Yin, L.; Zhang, J.-H.; Zhange, X.-F.; Zhao, L. Functionalities of Traditional Foods in China; Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences: Ibaraki, Japan, 16 October 2003; pp. 140–144. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, E.; Higgins, E.T. Regulatory focus and strategic inclinations: Promotion and prevention in decision-making. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1997, 69, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, T.Y.; Kim, S.; Sung, L.K. Fair pay dispersion: A regulatory focus theory view. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2017, 142, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezewska-Zychowicz, M.; Gębski, J.; Kobylińska, M. Food involvement, eating restrictions and dietary patterns in polish adults: Expected effects of their relationships (LifeStyle Study). Nutrients 2020, 12, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfattheicher, S.; Sassenrath, C. A regulatory focus perspective on eating behavior: How prevention and promotion focus relates to emotional, external, and restrained eating. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Armstrong, G.M.; Kotler, P.; Harker, M.; Brennan, R. Marketing: An introduction; Pearson: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Myszkowska-Ryciak, J.; Harton, A.; Lange, E.; Laskowski, W.; Wawrzyniak, A.; Hamulka, J.; Gajewska, D. Reduced Screen Time is Associated with Healthy Dietary Behaviors but Not Body Weight Status among Polish Adolescents. Report from the Wise Nutrition—Healthy Generation Project. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, S.J.; Nowson, C.A. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition 2007, 23, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Z.; Zhai, F.; Du, S.; Popkin, B. Dynamic shifts in Chinese eating behaviors. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 17, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, B.; Ford, K. Binge eating and dietary restraint: A cross-cultural analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1991, 10, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.E.; Kim, N.L.; Yang, H.; Jung, M. Effect of country image and materialism on the quality evaluation of Korean products. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 32, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatz, R.T.; Staub, E.; Lavine, H. On the varieties of national attachment: Blind versus constructive patriotism. Political Psychol. 1999, 20, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J.; Lwin, M.O. Regulatory focus theory, trust, and privacy concern. J. Serv. Res. 2009, 12, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dang, V.T.; Pham, T.L. An empirical investigation of consumer perceptions of online shopping in an emerging economy. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2018, 30, 952–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, E.N. The Food in China; Yale University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Andreyeva, T.; Kelly, I.R.; Harris, J.L. Exposure to food advertising on television: Associations with children’s fast food and soft drink consumption and obesity. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2011, 9, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Constructs | Item | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional personal value | I am a self-confident person. | [18] |

| I am the person who focuses on long-term orientation. | ||

| I am a person who is self-disciplined. | ||

| I always have a sense of obligation to everything in my life. | ||

| I always seek ways to be competitive in my life. | ||

| Modern personal value | I’m very easily indulgent | [35] |

| I’m a type of person who pursues individualism | ||

| I tend to pursue materialism and ostentation | ||

| I appreciate foreign cultures. | ||

| Materialism | I like a lot of luxury in my life | [65] |

| I admire people who own expensive homes, cars and clothes | ||

| I like to own things that impress people | ||

| My life would be better if I owned certain thing I do not have | ||

| The things I own say a lot about how well I’m doing in life | ||

| I would be happier if I could afford to buy more things | ||

| Buying things give me a lot of pleasure | ||

| Nationalism | People who do not wholeheartedly support China should live elsewhere | [66] |

| I would support my country right or wrong | ||

| If I criticize China, I do so for love of country | ||

| If you care about China, you should notice her problems and work to correct them | ||

| Promotion focus | I often devote time and energy to understand foods | [67] |

| I make efforts to show my interest in food consumption | ||

| I often seek information and obtain knowledge about food. | ||

| Traditional food purchase intention | If I need to eat, I intend to purchase Chinese food. | [68] |

| I intend to continue purchasing Chinese food in the future. | ||

| I will regularly purchase Chinese food in the future. | ||

| Fast food purchase intention | If I need to eat, I intend to purchase fast food. | [68] |

| I intend to continue purchasing fast food in the future. | ||

| I will regularly purchase fast food in the future. |

| Variable | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 238 | 34.40% |

| Female | 453 | 65.60% |

| Age | ||

| Under 20 | 125 | 18.10% |

| 20-under 30 | 424 | 61.40% |

| 30-under 40 | 100 | 14.50% |

| 41 and above | 42 | 6.10% |

| Marital status | ||

| Marriage | 502 | 72.70% |

| Not marriage | 189 | 27.40% |

| City | ||

| Beijing | 196 | 28.36% |

| Shanghai | 199 | 28.80% |

| Guangzhou | 296 | 42.84% |

| Education | ||

| High school and below | 187 | 27.10% |

| University | 486 | 70.30% |

| Master and above | 18 | 2.60% |

| Income | ||

| Under 500 USD | 186 | 26.90% |

| 500-under 1000 USD | 445 | 64.40% |

| 1000 USD or above | 60 | 8.60% |

| Note: n = 691 |

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | TPV | MPV | Nat | Mat | PRF | TFPI | FFPI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPV | 3.73 | 0.81 | 0.80 | ||||||

| MPV | 3.59 | 0.85 | 0.51 ** | 0.73 | |||||

| Nat | 3.65 | 0.83 | 0.53 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.80 | ||||

| Mat | 3.79 | 0.77 | 0.56 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.87 | |||

| PRF | 3.47 | 0.86 | 0.34 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.72 | ||

| TFPI | 3.49 | 0.87 | 0.49 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.87 | |

| FFPI | 3.62 | 0.85 | 0.51 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.83 |

| Constructs | Item | Factor Loadings | CR Value | AVE Value | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional personal value (TPV) | TPV1 | 0.644 *** | 0.898 | 0.639 | 0.894 |

| TPV2 | 0.820 *** | ||||

| TPV3 | 0.826 *** | ||||

| TPV4 | 0.858 *** | ||||

| TPV5 | 0.830 *** | ||||

| Modern personal value (MPV) | MPV1 | 0.679 *** | 0.823 | 0.537 | 0.818 |

| MPV2 | 0.758 *** | ||||

| MPV3 | 0.733 *** | ||||

| MPV4 | 0.764 *** | ||||

| Materialism (MAT) | MAT1 | 0.704 *** | 0.926 | 0.641 | 0.925 |

| MAT2 | 0.770 *** | ||||

| MAT3 | 0.826 *** | ||||

| MAT4 | 0.817 *** | ||||

| MAT5 | 0.810 *** | ||||

| MAT6 | 0.834 *** | ||||

| MAT7 | 0.836 *** | ||||

| Nationalism (NAT) | NAT1 | 0.892 *** | 0.923 | 0.749 | 0.923 |

| NAT2 | 0.881 *** | ||||

| NAT3 | 0.824 *** | ||||

| NAT4 | 0.864 *** | ||||

| Promotion focus (PROF) | PROF1 | 0.674 *** | 0.760 | 0.515 | 0.690 |

| PROF2 | 0.740 *** | ||||

| PROF3 | 0.736 *** | ||||

| Traditional food purchase intention (TFPI) | TFPI1 | 0.903 *** | 0.901 | 0.753 | 0.872 |

| TFPI2 | 0.872 *** | ||||

| TFPI3 | 0.827 *** | ||||

| Fast food purchase intention (FFPI) | FFPI1 | 0.799 *** | 0.872 | 0.695 | 0.901 |

| FFPI2 | 0.865 *** | ||||

| FFPI3 | 0.836 *** |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bu, X.; Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, Q.H.; Chen, C.-P.; Chou, T.P. Traditional or Fast Foods, Which One Do You Choose? The Roles of Traditional Value, Modern Value, and Promotion Focus. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7549. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187549

Bu X, Nguyen HV, Nguyen QH, Chen C-P, Chou TP. Traditional or Fast Foods, Which One Do You Choose? The Roles of Traditional Value, Modern Value, and Promotion Focus. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7549. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187549

Chicago/Turabian StyleBu, Xiangzhi, Hoang Viet Nguyen, Quang Huy Nguyen, Chia-Pin Chen, and Tsung Piao Chou. 2020. "Traditional or Fast Foods, Which One Do You Choose? The Roles of Traditional Value, Modern Value, and Promotion Focus" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7549. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187549