The Relationship between Female Top Managers and Corporate Social Responsibility in China: The Moderating Role of the Marketization Level

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theories and Hypotheses

2.1. CSR and Legitimacy

2.2. Gender Diversity

2.3. The Influence of Gender Diversity on CSR

2.4. Tokenism and Token Theory

2.5. The Moderating Role of the Marketization Level

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

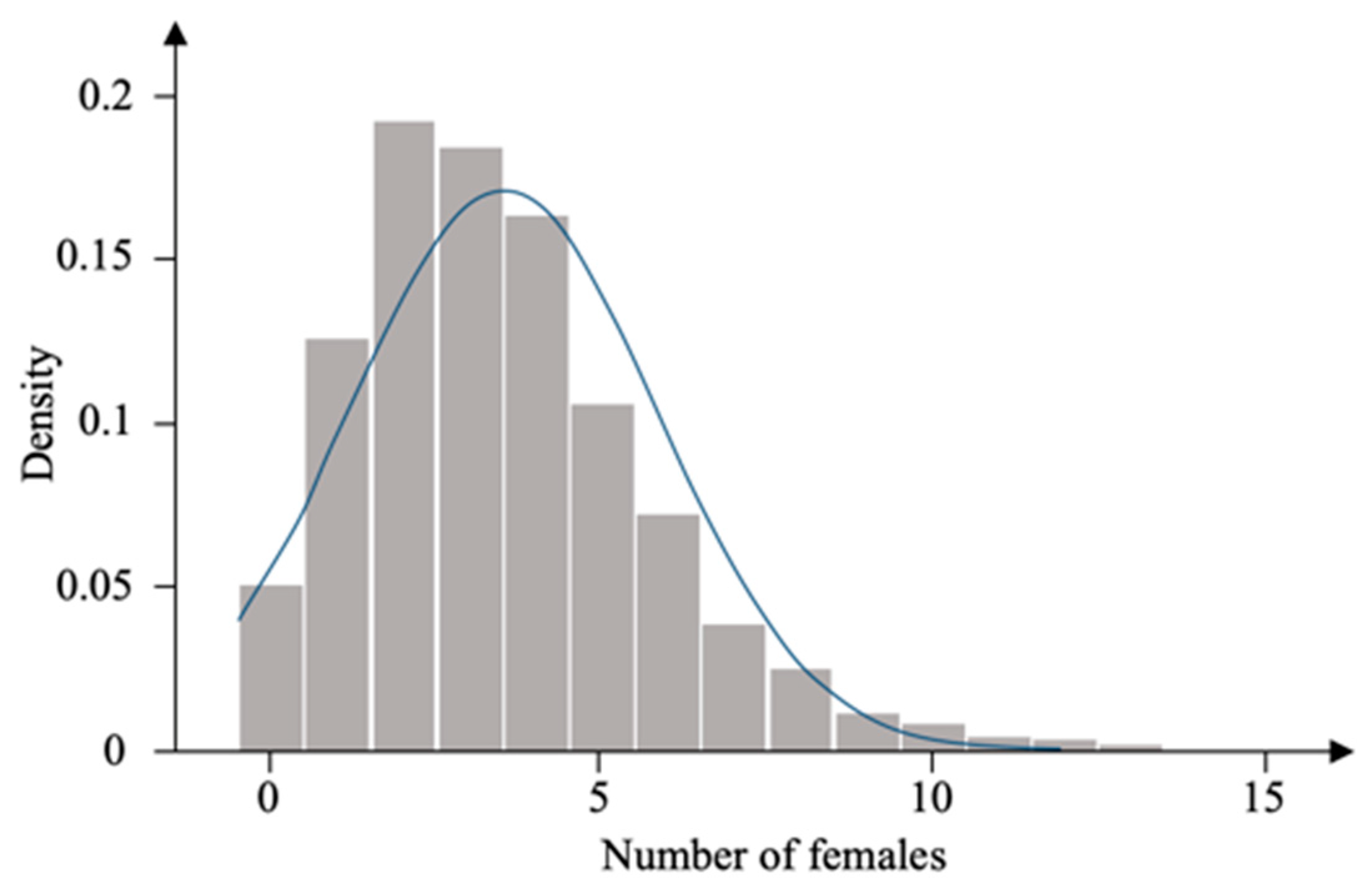

3.2.2. Independent Variable

3.2.3. Moderating Variable

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Estimation Approach and the Econometric Model

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

4.2. Multivariate Regression Analysis

4.3. Robustness Tests

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| First-Level Indicators | Second-Level Indicators | Third-Level Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Shareholders (A) Weight: 30% | Profitability (Aa) 10% | Return on equity (2%) |

| Return on assets (2%) | ||

| Profit margin of main operations (2%) | ||

| Profit margin of the costs and expenses (1%) | ||

| Earn per share (2%) | ||

| Undistributed profit per share (1%) | ||

| Solvency (Ab) 3% | Quick ratio (0.5%) | |

| Current ratio (0.5%) | ||

| Cash ratio (0.5%) | ||

| Equity ratio (0.5%) | ||

| Asset liability ratio (1%) | ||

| Return (Ac) 8% | Dividend financing ratio (2%) | |

| Dividend yield (3%) | ||

| Ratio of the dividends to the distributable profits (3%) | ||

| Disclosure (Ad) 5% | Penalty for improper disclosure (5%) | |

| Innovation (Ae) 4% | Product development expenditure (1%) | |

| Conception of technological innovation (1%) | ||

| Number of technological innovation projects (2%) | ||

| Employees (B) Weight: 15% The weight of consumption industry is 10% | Performance (Ba) 5% | Per capita income (4%) (3%) |

| Staff training (1%) (1%) | ||

| Safety (Bb) 5% | Security check (2%) (1%) | |

| Safety training (3%) (2%) | ||

| Care for employees (Bc) 5% | Consolation consciousness (1%) (1%) | |

| Consolation (2%) (1%) | ||

| Consolation money (2%) (1%) | ||

| Customer and consumer’s rights and interests (C) Weight: 15% Weight: 20% (consumption industry) | Quality of products (Ca) 7% | Quality management awareness (3%) (5%) |

| Quality management system certificate (4%) (4%) | ||

| After-sale service (Cb) 3% | Customer satisfaction survey (3%) (4%) | |

| Honesty and reciprocity (Cc) 5% | Fair competition of suppliers (3%) (4%) | |

| Training against commercial bribery (2%) (3%) | ||

| Environment (D) Weight: 20% Weight:30% (manufacturing) Weight:10% (service industry) | Environmental governance (Dd) 20% | Awareness of environmental protection (2%) (4%) (2%) |

| Environment management system certificate (3%) (5%) (2%) | ||

| Investment on environment protection (5%) (7%) (2%) | ||

| Types of sewage (5%) (7%) (2%) | ||

| Types of energy saving (5%) (7%) (2%) | ||

| Society (E) Weight: 20% Weight: 10% (manufacturing) Weight: 30% (service industry) | Contribution value (Ee) 20% | Ratio of income tax to total profit (10%) (5%) (15%) |

| Amount of public welfare donation (10%) (5%) (15%) |

References

- Rodríguez-Ariza, L.; Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B.; Martínez-Ferrero, J.; García-Sánchez, I.M. The role of female directors in promoting CSR practices: An international comparison between family and non-family businesses. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2017, 26, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setó-Pamies, D. The relationship between women directors and corporate social responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Ding, H. Board composition and corporate social responsibility: An empirical investigation in the post Sarbanes-Oxley era. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, S.; Rahman, N.; Post, C. The impact of board diversity and gender composition on corporate social responsibility and firm reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, C.; Rahman, N.; Rubow, E. Green governance: Boards of directors’ composition and environmental corporate social responsibility. Bus. Soc. 2011, 50, 189–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. Women on corporate boards of directors and their influence on corporate philanthropy. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. Corporate governance practices that address climate change: An exploratory study. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Zhang, Z. Women on boards of directors and corporate philanthropic disaster response. China J. Account. Res. 2012, 5, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deloitte. Women in the Boardroom: A Global Perspective, 5th ed.; Deloitte: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter, R.M. Men and Women of the Corporation; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman, A.J.; Cannella, A.A., Jr.; Harris, I.C. Women and racial minorities in the boardroom: How do directors differ? J. Manag. 2002, 28, 747–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G. Toward a political conception of corporate responsibility: Business and society seen from a Habermasian perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 1096–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El Ghoul, S.; Guedhami, O.; Kim, Y. Country-level institutions, firm value, and the role of corporate social responsibility initiatives. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2017, 48, 360–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nielsen, S.; Huse, M. The contribution of women on boards of directors: Going beyond the surface. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2010, 18, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, F.A.; Srinidhi, B.; Ng, A.C. Does board gender diversity improve the informativeness of stock prices? J. Account. Econ. 2011, 51, 314–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knippen, M.; Shen, W.; Zhu, Q. Limited progress? The effect of external pressure for board gender diversity on the increase of female directors. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 1123–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.C.; Rönnegard, D. Shareholder primacy, corporate social responsibility, and the role of business schools. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. Capitalism and Freedom; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Aupperle, K.E.; Carroll, A.B.; Hatfield, J.D. An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1985, 28, 446–463. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. A Friedman doctrine: The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. N. Y. Times Mag. 1970, 13, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, D.; Walsh, J.P. Misery loves companies: Rethinking social initiatives by business. Adm. Sci. Q. 2003, 48, 268–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orlitzky MSchmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajko, M.; Boone, C.; Buyl, T. CEO greed, corporate social responsibility, and organizational resilience to systemic shocks. J. Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N.; Bansal, P. The long-term benefits of organizational resilience through sustainable business practices. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 1615–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Vredenburg, H. Proactive corporate environmental strategy and the development of competitively valuable organizational capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 729–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surroca, J.; Tribó, J.A.; Waddock, S. Corporate responsibility and financial performance: The role of intangible resources. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 463–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.W. Corporate social responsibility in China: Window dressing or structural change. Berkeley J. Int. Law 2010, 28, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Daily, C.M.; Dalton, D.R. Women in the boardroom: A business imperative. J. Bus. Strategy 2003, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terjesen, S.; Sealy, R.; Singh, V. Women directors on corporate boards: A review and research agenda. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2009, 17, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berle, A.A.; Means, G.C. The Modern Corporation and Private Property; Transaction: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, E.F.; Jensen, M.C. Separation of ownership and control. J. Law Econ. 1983, 26, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Johannesen-Schmidt, M.C.; Van Engen, M.L. Transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles: A meta-analysis comparing women and men. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.; Dalziel, T. Boards of directors and firm performance: Integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, V.W.; Konrad, A.M.; Erkut, S.; Hooper, M.J. Critical Mass on Corporate Boards: Why Three or More Women Enhance Governance; Wellesley Centers for Women: Wellesley, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. Threshold models of collective behavior. Am. J. Sociol. 1978, 83, 1420–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kristie, J. The power of three. Dir. Boards 2011, 35, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Torchia, M.; Calabrò, A.; Huse, M. Women directors on corporate boards: From tokenism to critical mass. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkut, S.; Kramer, V.W.; Konrad, A.M. 18. Critical mass: Does the number of women on a corporate board make a difference. Women Corp. Boards Dir. Int. Res. Pract. 2008, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Xie, F. Do women directors improve firm performance in China? J. Corp. Financ. 2014, 28, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H. NERI Index of Marketization of China’s Provinces; National Economic Research Institute: Beijing, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, G.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H. The report on the relative process of marketization of each region in China. Econ. Res. J. 2003, 3, 259–288. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, G.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H. NERI Index of Marketization of China’s Provinces 2011 Report; National Economic Research Institute: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. Corporate social responsibility and access to finance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, B.; Petrovits, C.; Radhakrishnan, S. Is doing good good for you? How corporate charitable contributions enhance revenue growth. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, T.; Palepu, K.G. Winning in Emerging Markets: Spotting and Responding to Institutional Voids; World Financial Review: Duluth, GA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.P.H.; Wong, T.; Zhang, T. Politically connected CEOs, corporate governance, and Post-IPO performance of China’s newly partially privatized firms. J. Financ. Econ. 2007, 84, 330–357. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, A.W.Y.; Wong, R.M.K.; Firth, M. Can corporate governance deter management from manipulating earnings? Evidence from related-party sales transactions in China. J. Corp. Financ. 2010, 16, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qian, C. Corporate philanthropy and corporate financial performance: The roles of stakeholder response and political access. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 1159–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, J. Managerial Humanistic Attention and CSR: Do Firm Characteristics Matter? Sustainability 2018, 10, 4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, S.; Shao, Y.; Gao, S. CSR and firm value: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fan, G.; Wang, X. The Report on the Relative Process of Marketization of Each Region in China; Economic Science Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, M.; Schoar, A. Managing with style: The effect of managers on firm policies. Q. J. Econ. 2003, 118, 1169–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, Y. Philanthropic disaster relief giving as a response to institutional pressure: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 1377–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodar, N.G.; Porter, D.C. Basic Econometrics; Editura McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, J.J. Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error. Econometrics 1979, 47, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, L.; Li, Z.F. Managerial Attributes, Incentives, and Performance. Rev. Corp. Financ. Stud. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, K.; Kiel, G.C. The role of the board in firm strategy: Integrating agency and organizational control perspectives. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2004, 12, 500–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finegold, D.; Benson, G.S.; Hecht, D. Corporate boards and company performance: Review of research in light of recent reforms. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2007, 15, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A. Firm Size, Organizational Visibility and Corporate Philanthropy: An Empirical Analysis. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2006, 15, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Industry | Code | Firm-Year | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry, husbandry, and fishery | A | 253 | 1.49 |

| Mining | B | 433 | 2.54 |

| Manufacturing | C | 10,988 | 64.51 |

| Power, heat, gas, and water production and supply industry | D | 587 | 3.45 |

| Construction | E | 479 | 2.81 |

| Wholesale and retail | F | 973 | 5.71 |

| Transportation, storage, and postal services | G | 542 | 3.18 |

| Accommodation and catering | H | 62 | 0.36 |

| Technology services | I | 1013 | 5.95 |

| Real estate | K | 815 | 4.79 |

| Leasing and business services | L | 182 | 1.07 |

| Scientific research and technical services | M | 132 | 0.78 |

| Water conservancy, environment, and public facilities management | N | 192 | 1.13 |

| Education | P | 10 | 0.06 |

| Healthcare and social work | Q | 31 | 0.18 |

| Culture, sports, and entertainment | R | 213 | 1.25 |

| Comprehensive | S | 127 | 0.75 |

| Total | - | 17,032 | 100 |

| Variables | Description | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | CSR | Corporate social responsibility, given in five aspects: shareholder, employee, customer and consumer’s rights and interests, environment, society | Hexun.com database |

| Independent variables | Female | If the firm had a female in the top management team, this variable was coded 1, otherwise 0 | CSMAR |

| Moderators | Market index | The level of marketization level of a province or region | Published works |

| Control variables | Leverage | Debt-to-equity ratio, which is equal to the debt divided by the equity | Annual reports |

| Tobin’s Q | Equity plus the market value of liabilities and then divided by the year-end book value of its total assets | CSMAR | |

| SOE | State-owned enterprise: if the firm is owned by the state, this variable is coded 1, otherwise 0 | Wind | |

| Team size | The total number of members from a firm’s board of directors, board of supervisors, and top management team | CSMAR | |

| Industry dummy | Classified by China Securities Regulatory Commission | Wind | |

| Firm size | Logarithm of the firm’s assets, including all debt and equity | Annual reports | |

| ROE | Return on equity, which is equal to the net profit divided by the equity | Annual reports | |

| Firm age | Firm’s age since becoming public | Annual reports | |

| NumFemale | Number of female top managers in a firm | CSMAR | |

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CSR | 25.940 | 0.152 | ||||||||

| 2. Female | 0.949 | 0.002 | −0.025 | |||||||

| 3. Firm size | 12.970 | 0.011 | 0.288 | −0.070 | ||||||

| 4. ROE | 6.614 | 0.229 | 0.167 | 0.016 | 0.055 | |||||

| 5. Market index | 8.339 | 0.016 | −0.000 | 0.070 | 0.000 | 0.053 | ||||

| 6. Leverage | 0.432 | 0.002 | −0.010 | −0.037 | 0.414 | −0.113 | −0.117 | |||

| 7. Tobin’s Q | 2.972 | 0.110 | −0.025 | 0.015 | −0.181 | −0.009 | 0.019 | −0.030 | ||

| 8. Team size | 19.437 | 0.044 | 0.087 | 0.030 | 0.211 | 0.046 | −0.072 | 0.071 | −0.026 | |

| 9. SOE | 0.385 | 0.004 | 0.121 | −0.088 | 0.379 | −0.068 | −0.193 | 0.308 | −0.063 | 0.172 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Team size | −0.009 (0.026) | −0.002 (0.026) | −0.003 (0.026) |

| Leverage | −1.604 *** (0.911) | −1.634 *** (0.912) | −1.627 * (0.912) |

| SOE | 1.425 (1.298) | 1.393 (1.297) | 1.363 (1.297) |

| Firm value (Tobin’s Q) | 0.037 *** (0.014) | 0.036 *** (0.014) | 0.037 *** (0.014) |

| Firm size | 1.101 *** (0.347) | 1.080 *** (0.347) | 1.076 *** (0.347) |

| ROE | 0.026 *** (0.006) | 0.027 *** (0.006) | 0.026 *** (0.006) |

| Market index | −4.835 *** (0.242) | −4.789 *** (0.243) | −5.507 *** (0.489) |

| Female | −2.383 *** (0.838) | −1.782 * (0.910) | |

| Female × market index | 0.755 * (0.446) | ||

| Industry dummies | Included | Included | Included |

| Constant | 52.269 *** | 54.164 *** | 14.17 *** |

| R2 | 0.0517 | 0.0524 | 0.0526 |

| F | 3.81 | 3.82 | 3.82 |

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Female | 0.949 | 0.002 | |||||

| 2. Firm age | 10.206 | 0.059 | −0.016 | ||||

| 3. Market index | 8.339 | 0.016 | 0.073 | −0.120 | |||

| 4. SOE | 0.385 | 0.004 | −0.083 | 0.468 | −0.188 | ||

| 5. Firm size | 12.970 | 0.011 | −0.071 | 0.324 | 0.000 | 0.379 | |

| 6. Team size | 19.44 | 0.044 | −0.003 | −0.078 | −0.072 | −0.173 | 0.211 |

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CSR | 25.86 | 0.15 | |||||||||

| 2. NumFemale | 3.52 | 0.02 | −0.02 | ||||||||

| 3. Firm value (Tobin’s Q) | 3.01 | 0.12 | −0.03 | 0.01 | |||||||

| 4. ROE | 6.68 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.05 | −0.01 | ||||||

| 5. Firm size | 12.95 | 0.01 | 0.30 | −0.11 | −0.18 | 0.059 | |||||

| 6. Team size | 19.47 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.36 | −0.03 | 0.045 | 0.21 | ||||

| 7. SOE | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.12 | −0.12 | −0.06 | −0.067 | 0.36 | 0.17 | |||

| 8. Market index | 8.38 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.049 | 0.01 | −0.07 | −0.18 | ||

| 9. Leverage | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.08 | −0.03 | −0.109 | 0.40 | 0.07 | 0.30 | −0.12 | |

| 10. Inverse Mills ratio | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.17 | −0.20 | −0.10 | −0.023 | 0.52 | 0.03 | 0.68 | −0.60 | 0.28 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Market index | 0.069 *** (0.010) | 0.071 *** (0.010) |

| SOE | −0.254 *** (0.043) | −0.323 *** (0.047) |

| Firm size | −0.070 *** (0.015) | −0.079 *** (0.015) |

| Team size | 0.009 *** (0.003) | 0.011 *** (0.003) |

| Firm age | 0.013 *** (0.003) | |

| Industry dummies | Included | Included |

| Log-likelihood | −2560.35 | −2553.62 |

| Intercept | 2.023 *** (0.248) | 1.992 *** (0.249) |

| 13.47 *** |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firm value (Tobin’s Q) | 0.023 * (0.014) | 0.023 * (0.014) | 0.023 * (0.014) |

| ROE | 0.020 *** (0.006) | 0.020 *** (0.006) | 0.020 *** (0.006) |

| Firm size | −1.618 *** (0.449) | −1.656 *** (0.450) | −1.650 *** (0.450) |

| Team size | 0.413 *** (0.050) | 0.454 *** (0.055) | 0.453 *** (0.055) |

| SOE | −10.018 *** (1.848) | −10.123 *** (1.849) | −10.106 *** (1.850) |

| Market index | −0.801 * (0.476) | −0.731 (0.478) | −0.731 (0.478) |

| Leverage | −1.632 * (0.915) | −1.618 * (0.915) | −1.611 * (0.915) |

| Inverse Mills ratio | 213.807 *** (22.171) | 214.841 *** (22.177) | 214.497 *** (22.21) |

| NumFemale | −0.229 * (0.135) | −0.288 (0.255) | |

| NumFemale2 | 0.005 (0.019) | ||

| Industry dummies | Included | Included | Included |

| Intercept | 32.101 *** (4.908) | 31.968 *** (4.909) | 32.046 *** (4.917) |

| F | 29.87 | 28.59 | 27.29 |

| R2 | 0.0589 | 0.0592 | 0.0592 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, Q.; Chen, S.; Chen, P. The Relationship between Female Top Managers and Corporate Social Responsibility in China: The Moderating Role of the Marketization Level. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187730

Lu Q, Chen S, Chen P. The Relationship between Female Top Managers and Corporate Social Responsibility in China: The Moderating Role of the Marketization Level. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187730

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Qianwen, Shouming Chen, and Peien Chen. 2020. "The Relationship between Female Top Managers and Corporate Social Responsibility in China: The Moderating Role of the Marketization Level" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187730