Abstract

Farm mechanization can promote the economic sustainability of small farms and in the context of cereal-legume systems strengthen plant protein-based diets, which support human health and environmental sustainability. However, mechanization inevitably displaces hired laborers who depend on manual farm work for their income. Few studies have systematically analyzed the differential effects on women and men hired labor. Here, we use primarily qualitative data from Myanmar and Bangladesh to test the hypothesis that the effects of mechanizing mung bean harvesting—which is now commencing in both countries—are likely to weaken women hired workers’ economic and personal empowerment. We focus on rural landless women laborers as an important part of the agricultural labor force. The results broadly confirm the hypothesis, although there is variation between the research sites. Harvesting mung beans is the only fieldwork task available to many landless women, particularly married women with children, in both countries. Gendered restrictions on women’s mobility and their role as family caregivers, as well as norms about appropriate work for women and men, restrict women’s options regarding alternative work both locally and further away. The effects are likely to be particularly negative in locations with minimal off-farm economic diversity and more restrictive gender norms. Overall, men across all sites will be less affected since their participation rates in harvesting and post-harvest processing are low. They are less restricted by gender norms and can travel freely to find work elsewhere. However, women and men in low asset households will find it problematic to find alternative income sources. Less restrictive gender norms would help to mitigate the adverse effects of farm mechanization. It is important to invest in gender transformative approaches to stimulate change in norms and associated behaviors to make a wider range of choices possible.

1. Introduction

Across much of tropical Asia smallholder farms are proving productive, resilient and ever-capable of transformation [1]. One expression of transformation is small-scale mechanization and associated practices. Mechanization raises the productivity of smallholder farms, thereby contributing to their economic sustainability and survival in the face of the rising labor costs. The availability of small farm machinery in association with machine rental markets is facilitating mechanization on ever-smaller and fragmented holdings [1,2,3,4]. However, mechanization implies the inevitable displacement of family, and hired, labor. This potentially creates a trade-off between the economic and social sustainability of smallholder farms and the economic and social sustainability of households depending on agricultural wage labor for their livelihood.

Our article focuses on the actual and potential impacts of mechanization in mung bean harvesting on landless agricultural laborers, particularly women since they dominate the harvesting workforce, in Myanmar and Bangladesh. The mung bean is an important legume crop in these countries and contributes to smallholder incomes and family nutrition. During the agricultural year 2017/2018, mung bean was grown on 37,600 hectares in Bangladesh and 1,200,000 hectares in Myanmar [5,6]. Raising the profitability of mung bean production is important to maintain and expand its role in local food and agricultural systems. Including legumes in crop rotations mitigates greenhouse gas emissions by reducing the need for nitrogen fertilizer [7,8]. The role of legumes such as mung bean as part of healthy diets is also increasingly well recognized, particularly as a source of plant-based proteins, which contribute to better human health and environmental sustainability [9,10]. However, the need for labor intensive, repeated hand harvesting of mung bean pods is a major threat to the economic sustainability of production as wages rise and less agricultural labor is available. At the same time, the ending of hand harvesting as means of paid employment for large numbers of women has potentially significant consequences for their livelihoods. This, in turn, has implications for their empowerment in various domains and threatens equitable and socially sustainable development in rural areas. Mechanization of mung bean harvesting has been observed in parts of India [11] and Pakistan [12].

Field research was carried out between 2018 to 2020 as part of an Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) funded project “Improved Mung bean Harvesting and Seed Production Systems for Bangladesh, Myanmar and Pakistan” (https://www.aciar.gov.au/project/CIM-2016-174). The project is coordinated by the World Vegetable Center with key national partners being the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute, the Department of Agricultural Research in Myanmar and the Pakistan Agricultural Research Council. The aim of the project is to establish and validate a practical and economically viable system to mechanically harvest mung beans, using adapted combine harvesters, on smallholder fields in each country. Currently, hand harvesting accounts for around half of the production costs of mung beans. This restricts its expansion despite high demand and its nutritional importance. The project recognizes that women spend considerable time hand-harvesting pods and will therefore lose work. The mung bean is usually harvested three times due to staggered ripening of the bean pods, and post-harvest processing is also necessary. The hypothesis of the research conducted in Myanmar and Bangladesh was that the (potential) impacts of mechanizing mung bean harvesting are likely to weaken women hired workers’ economic and personal empowerment. In our study, we focused on rural landless women laborers because they are a principal source of agricultural labor in mung bean harvesting in both countries. The research questions are:

- How is mechanizing mung bean harvesting likely to impact upon the income of women workers?

- Are women workers likely to be able to innovate into alternative sources of income?

- How might the loss of income affect the economic and personal empowerment of women workers?

Regarding the final question, we are interested in moving beyond merely mapping changes to the ability of women to earn income and instead developing a richer understanding of whether the loss of income from harvesting mung beans might hamper the ability of women to make a meaningful or good life [13]. As part of this, we consider that defining—and realizing—one’s aspirations is critical if one is to be able to live a life in which women and men are able “to imagine, to wonder and … to know” [14]. Hence, we also explore whether women’s work contributes to their sense of wellbeing.

The hypothesis and research questions are intrinsically relational questions. They can only be properly assessed by examining the importance of mung beans to men, either as workers in the mung bean industry or as partners to women working with mung beans. We therefore present data related to men’s work and benefits related to mung beans as well.

1.1. Selected Studies on the Impact of Mechanization on Women Hired Labor

Women and men experience transformation processes in farm systems differently. Gender norms, attitudes and power relations differentially frame the ways in which women, and men, perceive and are able to capture opportunities for change [4,15]. “Society’s understandings of what is acceptable for women and men to be, do, own and control may […] pose barriers” to women’s ability to take advantage of new technologies [16] or to adjust to their implications for their livelihoods. The effects of new technologies upon women’s and men’s work, and the benefits they accrue, vary between members of a household, between households and between social groups [17,18,19,20]. Technologies that alter demand for labor rarely have the same implications for women as for men because each gender generally conducts different tasks during production, harvesting, post-harvest processing and storage. Other criteria of social difference, such as age, caste, class and ethnicity—and the size and type of household resource portfolios—also affect the ways in which labor is affected when new technologies are introduced. Some technologies increase women’s workloads, others diminish it, and others create new income generation opportunities [18].

Research shows that the impacts of mechanisation on hired women are mixed. In Vietnam, for instance, the introduction of drum seeder technology caused 97% of landless women to lose their work in gap filling and weeding. Nearly half (43%) found it difficult to find alternative sources of income [21]. In Bangladesh, the introduction of mechanical rice mills replaced women’s work in hand-pounding rice. Since gender norms prevented women from leaving their homestead, they could not look for alternative employment opportunities and thus lost an important income source. In Indonesia, though, poor women impacted by the same technology did not face mobility restrictions and entered other occupations [18]. In the Philippines, the introduction of mechanical threshers meant women initially lost work. However, faster threshing was a factor in allowing two crops of rice instead of one to be grown, thus increasing opportunities for women in transplanting, weeding and harvesting [18]. By way of contrast, gender inequalities were exacerbated when high yielding varieties of wheat—a male-labor dominated crop—were introduced in India between 1956 and 1987. Female wages declined whilst male wages increased [22]. In association with the local gender division of labor, and gender norms, therefore, mechanization has the potential to masculinize, or feminize opportunities for hired labor in crops.

The data presented so far appears to imply that hired workers lack agency, and that the gendered division of labor does not change. However, gender norms change over time, sometimes incrementally such that change is hardly perceived [23], and sometimes more rapidly [24]. In some contexts, women struggle openly for their rights. Rigg [25] describes how in Malaysia between 1970 and 1979 women workers organized against male landowners for higher wages and the right to work in labor gangs (rather than being employed individually). Ultimately, the women failed in their initiative as the introduction of direct seeders undermined the bargaining power of women transplanters, the interests of wives and daughters were pitted against those of men in the household and the wider political economy reduced the price of capital relative to labor [25]. In other contexts, broader processes are changing “who does what” in farming. In India, Nepal and Bangladesh for example, men are out-migrating from rural areas in both the short- and long-term. As a consequence women, as family members or as hired laborers, are taking on an increasing proportion of agricultural work [4,26,27] and in some situations women are seizing the chance to become decision-makers [28,29,30]. Finally, it is well established that across South and East Asia, agricultural laborers are moving out of the sector in search of better paid jobs, as domestic helpers, in service industries, in construction and in factories [31,32].

This brief roundup suggests that the implications of mechanizing field processes for women and men agricultural laborers are complex and difficult to generalize. The degree to which women and men hired laborers are “winners” and “losers”, and the degree to which they can take some control over their destinies, can only be established with reference to specific forms of mechanization in specific locations. The next sub-section provides the context of our study by reporting on mechanization processes in Myanmar and Bangladesh.

1.2. Agricultural Mechanization Processes in Myanmar

Myanmar has experienced structural transformation since 2011 leading to new employment opportunities in the agricultural and industrial sectors. Economic growth and reforms in the non-farm sector have accompanied attempts to intensify agricultural production and mechanization to meet production targets [3]. The Government of Myanmar (GoM) National Strategy on Poverty Alleviation and Rural Development (NSPARD) states “postharvest works in pulses are still weak in using machines. Harvesting, threshing, grading and cleaning process are still made by hand”. The GoM’s Country Statement on Agriculture, prepared by the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (MOAI) in 2014, urges full mechanization. Machinery supply businesses are opening across the country, even in distant rural locations. Small farmers are increasingly able to access machinery due to the declining real price of some types of machinery, increased availability of financial resources through formal sector lending and the rise of rental markets [31,33].

There are three types of agricultural labor in Myanmar: unpaid family labor, casual hired labor (paid per day or per task) and seasonally-hired labor [34]. The actual combination varies considerably across the country [35]. Whilst a variety of households, including smallholders, provide labor [31], landless households in particular have provided farms with labor for generations [3,35]. These linkages are unravelling due to the emergence of new industries, urbanization, improved market and road infrastructure and internal and international migration [3]. Migrants from the Central Dry Zone highlight push factors as being a desire for a higher income, unwillingness to work in agriculture and insufficient land [31]. Aspiration is important, with many parents hoping to save their children a life of drudgery by earning better wages elsewhere [1,36]. Even when on- and off-farm wages are similar, acquiring new skills offers landless people the chance to start their own business and become independent [3]. In the Central Dry Zone, long-term migration is fairly equally split by gender (46% women) whereas short-term migration is dominated by men (70% men). This is largely because short term migrants work in jobs culturally constructed as male like carpentry, whereas long-term jobs are more likely to include opportunities considered suitable for women in factories and in services [31].

As a consequence of these changes, farmers are increasingly experiencing labor shortages at critical times [3,33]. Between 2015 to 2018, the percentage of hired labor in agriculture decreased from 36% to 26%, and the proportion of women hired labor decreased from 46% to 43% (FAO). Real wage rates for hired agricultural laborers are increasing as hired laborers exploit their newly won bargaining power [3,33]. In the Central Dry Zone, real daily wages reportedly rose by 42% for women, and 37% for men between 2012 and 2016. Gender inequalities remain, however, with women earning on average 20% less than men [31]. The bargaining power of laborers is not only due to the dynamic effect of other opportunities. Local relationships—which differ around the country—structure the ability of landless people to negotiate wages [35]. Mechanization is also propelling women and men workers out of agricultural work. Whilst almost all farm households in the Central Dry Zone provide some hired labor to others, landless households provide 61% of all hired labor (11.7 million days). Hired work generates an average of 464 USD per year to these landless households. However, over the past decade (to 2017) mechanization of farm processes reduced agricultural labor days for landless households by an estimated one million days, resulting in a loss of potential agricultural wages of 2.7 million USD, equivalent to 41% of household income. Landless households have compensated, though, by seeking other work. This has increased their overall income by an average of 182 USD per year [31].

There is little data on how women and men who depend on agricultural labor for their livelihoods view the changes brought by mechanization. A small study in the Ayerwaddy Delta shows that smallholders and landless laborers have different, gendered perspectives on labor shortages in agriculture [37]. Farmers complain that they have to pay higher wages, and bemoan that “there are no more female transplanting or harvesting teams in the villages as we had before”. However, women laborers complain that, due to mechanization, there is almost no paid work for women (ibid.). This situation arises because the division of labor is strongly gendered, both on- and off-farm [31]. In other words, the crisis in farm labor is partly produced by gender norms that confine women and men to certain tasks.

1.3. Agricultural Mechanization Processes in Bangladesh

The Government of Bangladesh (GoB) has supported agricultural mechanization to intensify production for many years and, as a consequence, mechanization is more widespread than in other parts of South Asia [2,38]. Today, over half a million power tillers prepare 80% of Bangladesh’s cropland and further mechanization is proceeding apace [2]. There are strong rental markets, with owners of agricultural machinery servicing even the smallest farms [2].

In Bangladesh, labor is transacted under three major arrangements: seasonal or annual contract, daily wage contract and piece-rate contract. Around 35% of rural households provide agricultural labor [39]. Wage rates for hired labor vary by gender, task, season, ethnicity and location [40,41]. The agricultural year lasts around 5 to 6 months, with men workers obtaining, on average, 10–20 days of work per month. The peak season provides around 30–45 days of work. During this time, men migrate from labor surplus areas to labor deficit areas around the country. Women in many parts of the country are increasingly active in fieldwork alongside post-harvest processing, homestead gardening and managing household fish ponds [4]. Over the past twenty years, the male labor force participation rate (in all sectors) has declined from 84% in 1999/00 to just above 80% (2016/17) whereas the female labor force participation rate increased from 23.9% to 36.3% over the same time period [42]. However, the participation of women in off-farm work of all kinds has stagnated since around 2010, with a concomitant rise in low-skilled agricultural work since 2013. Indeed, women now dominate the agricultural labor force, though much of this is unpaid (ibid).

Despite some opportunities opening up for women in agriculture, purdah—female seclusion—continues to limit women’s mobility and restrict their interactions with non-family men, thus placing significant constraints on their ability to earn an income [4,42] There remains a bias against women agricultural laborers, with women often being employed when men are unavailable [43]. The daily agricultural wage varies around the country and by task, but the female to male wage rate ratio narrowed from 73% in FY2010 to 78% in [41].

2. Materials and Methods

In this article, we report primarily on data derived from qualitative research, though we bring in insights from associated quantitative research. The quantitative research identified the districts and communities to be sampled, and the qualitative research took place in four of those pre-selected locations. We now describe the methodology for each.

2.1. Quantitative Research

The quantitative research used a stratified sampling strategy to interview mung bean farmers in major mung bean producing areas of Bangladesh and Myanmar. Data collection took place between July 2018 and February 2020. One set of survey questions related to farmer labor hiring practices. Gender-disaggregated labor data were collected separately for 11 activities from ploughing through to transporting the harvest to the market. This included data on labor provided by hired laborers, family laborers, laborers that did not receive monetary payments, and children. For each type of laborer, and activity, respondents reported the number of days of work, the average number of persons involved, and the average number of hours spent. From this we calculated standardized 8-h labor-days. Extreme outliers were removed. (Where the total labour input per hectare was more than two inter-quartile ranges above the 3rd quartile, we replaced it with the largest remaining value in the country. We replaced 9 outliers in Bangladesh and 26 in Myanmar. All contributing labour sources and their wages were reduced by the same factor).

In Myanmar, the Magway and Sagaing Regions were chosen to represent the Central Dry Zone while Bago and Yangon were chosen to represent Lower Myanmar. In Bangladesh, the Natore and Pabna Districts were selected to represent the north and Jhenaidah to represent the south. Patuakhali was also included, though quantitative data collection was prevented by the COVID-19 pandemic. In each administrative area the research team identified three townships (in Myanmar) or four unions (in Bangladesh) where mung bean production is concentrated. Two to three villages per township/district were randomly selected to ensure 125 interviews per region/district. The survey included 334 mung bean farmers from 40 villages in Bangladesh and 518 farmers from 44 villages in Myanmar (Table 1).

Table 1.

Geographic distribution of the quantitative sample of mung bean farmers.

As the sampling is not proportional to the area planted with mung bean, we weight the data based on the official statistics of mung bean production area in the regions/districts and the area planted by each farmer. The weights represent the importance of the area planted with mung bean by each farm compared to the national mung bean production area.

2.2. Qualitative Research

The qualitative research sites were purposively selected from the quantitative research sampling frame based on the national partners’ knowledge of the sites.

Seven research activities were conducted in each research site (Table 2). These included four sex-disaggregated focus group discussions (FGDs), (4 with women, 3 with men) held with facilitators of the same gender, and one wife-husband activity. Additional activities informing this study include a community profile (mixed gender); and a mung bean value chain analysis with associated individual key informant interviews (KIIs) (mixed gender). Tools were partly based on the GENNOVATE (gender, norms and innovation) research guide [24].

Table 2.

Qualitative research tools applied in Myanmar and Bangladesh, showing the average numbers of participants per tool.

FGDs 1 and 2 investigated the role of mung bean in the local agricultural system and its relative importance by activity—compared to other income generation opportunities—in women’s and men’s livelihoods. FGD 3 asked a couple to reflect individually and then together on their visions for the future. Discussion focused on (gendered) factors hampering or facilitating vision realization. FGD 4 asked respondents to explore the respective abilities of women and men to respond to mechanization through innovating into new livelihoods. FGD 5 asked women to reflect on their sense of empowerment. As part of these exercises, respondents were asked to reflect on who makes key decisions on the topics discussed, and in relation to the management of their asset portfolios. In all FGDs, forces driving system change, and their effects, were explored. To help understand gender norms, and if they are changing, all respondents in all FGDs were asked to discuss what gender equality meant to them.

Sampling criteria were as follows: 6 to 8 respondents per sex-disaggregated FGD. They had to be landless women and men workers known to regularly participate in mung bean harvesting (or in mung bean production and post-harvest tasks). Every respondent had to come from a different household, and respondents had to be drawn from different locations in each community. Respondents for the community profile (average 8 per community, women and men) were expected to be of high standing in the community and to be able to contribute diverse knowledge: for instance, elected village leaders, health care staff and teachers. The value chain exercise was conducted more opportunistically, with respondents selected on the basis of their known participation in the mung bean value chain.

Village 1 is in Lower Myanmar. It had 917 households in 2019. Of these, 600 HH (around two thirds) were landless and worked as hired laborers. We met members of 52 households (8.67% of eligible households). Village 2 in the Central Dry Zone in Myanmar had 214 households in 2019. Of these, 98% (210 households) provided hired workers. About one third (30% = 63 households) worked primarily as agricultural laborers. Of these, we met with 46 households (73% of eligible households). Village 3 in northern Bangladesh had around 785 households. Of these, 456 households provided hired labor (58%) and we met members of 30 such households (6.6%). Village 4 in southern Bangladesh had 687 households in 2019 with 376 providing hired labor (54%). Of these, we met representatives of 54 (14.3%) of the eligible households.

2.3. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Table 3 presents the demographic characteristics of the FGD and husband-wife activity respondents in Myanmar. In both sites, all respondents lived locally and were aged between 40 and 46 years old. The youngest was 19 and the oldest 72. Whilst most women had completed primary education, more men had completed secondary and tertiary schooling.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of hired workers in Myanmar and Bangladesh.

In Bangladesh, hired women and men workers in both sites live in the same community as their employers (Table 4). Hired workers derive mainly from low and middle income households in the community. The average age of respondents was between 40 and 43 years old with the youngest being 15 and the oldest 79 years old. Most respondents, particularly women, were married with 4 to 5 family members. Women respondents had less formal education than men in Village 3 but were more educated than men in Village 4.

Table 4.

Labor-days and wages per hectare of mung bean.

An important feature of the demography is that almost all women sampled were married with families. They participated more than any other household typology in mung bean harvesting due to their responsibilities for childcare, household maintenance and other tasks around the home. This hampered their ability to participate in off-farm work in nearby towns and villages, or further afield.

2.3.1. Site Characteristics in Myanmar

Village 1 is in Bago East Region, Taungo District, in Lower Myanmar. Almost everyone grows mung bean in rotation with paddy rice. Overall, the community exhibits low crop and livestock diversity. This is related to its challenging agro-ecological environment. The village floods to a depth of two meters from late July for three months with people moving around by boat. Livestock need to be housed in wooden buildings on stilts with fodder brought to them by boat. Around one third of the land is lowland and hard to mechanize. Overuse of pesticides is reducing biodiversity leading to ever more pests, and less wild foods for local people. There are very few local work opportunities, particularly for married and older women. Apart from working in mung bean and a few other crops, such women mostly rely on open access resources for income, for example by picking and selling water spinach (ipomea aquatica) leaves, and fishing. This access could be ended at any time by the authorities. Men earn money as carpenters, masons and in fieldwork. The local town is about 7 km away. Community profile respondents consider 1/3 of households to be middle-income, and 2/3 to be low income. The latter are landless—though they have homestead gardens of around 0.1 acre—and depend on working as agricultural laborers. Wholesalers buy mung bean for export, and often pre-finance production as well. There is a small buyer in the village as well. Farmers began using power tillers and tractors for land preparation, and mechanical rice threshers, a decade ago. Some farmers started using combine harvesters for rice in 2015. In 2017 the first few farmers started harvesting mung bean using a combine, with two thirds using combines in 2019. Rapid take up is due to catastrophic floods in 2018 plus heavy rains just prior to harvest in 2019 which led to farmers panicking. One third of farmers grew mung bean on low land which is unsuitable for machinery and so hand harvesting has continued. Research took place a week or so after the mostly mechanized mung bean harvest in February 2019.

Village 2 is located in Magway Region, Natmauk District in the Central Dry Zone. On-farm diversity is higher than in Village 1. Sesame, groundnut and pulses, including mung bean are principal crops. Mung bean is mainly line sown as a sole crop but some farmers intercrop with pigeon pea. Maize, chickpea, onion and sunflower are also grown. Year-round irrigated vegetable production using tube wells began in 2012. Some people raise poultry, cattle, pigs and sheep. Almost everyone makes rope from toddy palm which is sold nationally. Community profile respondents considered about 2% of households to be wealthy and around 96% of households to be middle-income. The remainder (2%) are low-income households. Wage laborers are drawn from the latter two categories. The local town is 1 km distant. Village 2 is considerably better developed than Village 1 with many more options for generating income. Mechanization has proceeded slowly, largely because rice is primarily a subsistence crop. Mechanization of land preparation using tractors and power tillers began in 2008–2009 yet was only fully mechanized in 2016. Rice threshers have been used for twenty years but mechanized harvesting of monsoon rice was only introduced in 2018. In that year, a private company showed women and men how to use combine harvesters for rice but to date take up has been low. Research took place in July 2019, the peak labor time for farmers and laborers.

2.3.2. Site characteristics in Bangladesh

Village 3 is in Lalpur Upazilla in Natore District in northern Bangladesh. Apart from mung bean, farmers grow paddy, wheat, jute, sugarcane, cotton, pulses and vegetables. Demand for agricultural labor is high. As a community profile respondent (man) explained, “There’s been a revolution in agriculture. Productivity has increased tremendously. About 10 years ago we got 5 mon [1 mon = 40 kg] boro rice from 33 decimals of land but now we get 20 to 25 mon from the same land area. Previously lentil productivity was 2 mon per bigha but now it is 8”. Women’s participation in most fieldwork tasks is non-existent to low, though some opportunities are emerging in horticultural crops, and in weeding crops like jute and sugarcane. Middle- to high-income men reject manual labor as demeaning. Despite the general bar on fieldwork, women and hired laborers (nearly all women) always work in mung bean harvesting and post-harvest processing, and women are increasingly working on the family farm and in road maintenance. One older woman we met, a widow, worked alongside men on all tasks, including sugarcane, but she was seen as an exception. Women, and men, are engaged in cottage industries such as making molasses, tailoring and making sweets. All women tend livestock. Over the past decade, women have become much more visible. Whilst they still do not sell or buy groceries or crops in the market, some women now shop for other items. Women also engage in farmgate sales to local businessmen. Their mobility is considerably more limited than men’s, and they require men’s permission to leave home. However, few women are restricted to the household. Today, all girls go to school and are more likely than boys to transition to secondary school because the poorest families often take boys out to earn an income. Whereas almost no women were teachers a decade ago, they now form the majority—partly as a consequence of government quotas. Poor men work locally and through migration to harvest paddy. Men typically work 15 days locally in harvesting rice, and 15 days elsewhere. The in-kind payment covers, for many, their family’s rice requirements for the entire year. Machinery including power tillers, threshers and sprayers have been introduced through rental markets. Some cattle-drawn ploughs are still in use. Rice is hand-harvested, though a few people have seen combine harvesters being used to harvest rice elsewhere. Overall, Village 3 has not experienced significant mechanization.

Village 4 is a southern coastal community located in Sreerampur Union in Dumki Upazilla in Patuakhali District in southern Bangladesh. It is highly prone to natural disasters including cyclones in 2007 and 2009, and hailstorms and drought hit every year. There is limited scope for off-farm employment so most people make a living from farming. Men typically fish in rivers and canals and others work in rickshaw pulling, motorbike-taxi driving, making and repairing of fishing nets, and in shops and restaurants. Very poor women work as servants—there are almost no other opportunities for women available. About half the population rear poultry. Wealthier farmers have buffalo and cattle, and poorer ones raise goats. Aquaculture is increasing. Experience of mechanization is limited, though many farmers use power tillers.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Data Findings

In the quantitative survey, we found that mung bean farmers planted on average 0.18 ha of mung bean per year in Bangladesh and 3.42 ha in Myanmar (Table 4). Each hectare planted with mung bean provided on average 35 labor-days of employment across all tasks for hired women in Bangladesh and 31 in Myanmar. Hired men obtained about 10 labor-days across all mung bean tasks in Bangladesh and about 9 in Myanmar. Taken together, hired laborers provided about half of all labor required in Bangladesh, and about 81% in Myanmar where the planted areas are larger. Particularly for women, most of their work and thus wages were in mung bean harvesting. In Bangladesh, farmers paid on average a total of 115 USD per hectare to women hired for harvesting, whilst farmers in Myanmar paid women about 110 USD per hectare (Currencies are converted using the annual average of the official exchange rate to USD of 2018 for Myanmar (1429.808 MMK/USD) and of 2019 for Bangladesh (84.454 BDT/USD).) As fewer men were hired for the harvest, farmers paid on average 9 USD per hectare to men in Bangladesh and 16 USD per hectare to men in Myanmar. In both countries, wages for all activities on the fields before the harvest total about 40 USD per hectare for men and women combined. This work is mostly done by men workers in Bangladesh but equally shared between men and women in Myanmar. Post-harvest activities on the farm provide about 4 USD per hectare to women and men hired workers in Bangladesh and 9 USD per hectare in Myanmar. Combining these results with national statistics of mung bean production [5,6], our data suggest that in Bangladesh the mung bean harvest provides ca. 4.75 million USD of annual income to rural women laborers and 0.37 million USD to men laborers. In Myanmar it provides 134.75 million USD to hired women and 20.33 million USD to hired men.

3.2. Qualitative Data Findings

The data are combined from all seven qualitative research tools unless otherwise indicated. All data refer specifically to the four study sites and cannot be assumed to represent the situation in each country in general.

3.2.1. Research Question 1. “How Is Mechanizing Mung Bean Harvesting Likely to Impact upon the Income of Women Workers?”

To answer this, we assessed the number of days women and men work in mung bean harvesting, and the wages received. Whilst the quantitative survey shows the importance of wages at the population level, the qualitative data shows the relative importance of income from mung bean harvesting compared to wages in other forms of fieldwork. We further considered that it was important to break down the actual tasks women and men perform in mung bean harvesting so as to avoid assumptions about their work. For instance, women’s work in land preparation and pesticide spraying is often overlooked. Given the small sample of respondents, we do not present how many respondents in our sample earned a specific income. Rather, we provide the full range of data provided by the respondents in relation to days worked and income.

In our research sites in both countries, hired workers are recruited from within the community directly by farmers rather than through agents. Hired laborers are paid only in cash. The exception in all sites is when a hired laborer is indebted to the farmer due to borrowing money; then they must work on the farmer’s fields to repay the loan. In Myanmar, in Village 1, farmers hire laborers as individuals but in Village 2, a farmer asks one hired laborer to organize a group of men, or women, depending on the task. Often, when women obtain work, their husband or other family members must take on their household and childcare tasks. In Bangladesh, women prefer to work with the same group of women year after year. Some men form groups, and others work as individuals. Women we met in Bangladesh needed their husband’s permission to work in mung bean harvesting or any other task. They also performed the majority of household and care work though many men contributed in minor ways to childcare, cooking etc.

Table 5 shows the gender division of labor in mung bean, and the average number of days worked, in Villages 1 and 2 in Myanmar, and in Villages 3 and 4 in Bangladesh. It should be noted that in Myanmar in our two sites, the women to men labor force in mung bean harvesting averages 80% women to 20% men (or at the most 70%:30%). In the Bangladesh sites, very few men (a handful) work on harvesting mung bean. The figures in the table thus do not mean that all men work on mung bean harvesting, but rather show the number of days worked by men on average should they work in harvesting mung bean.

Table 5.

Labor-days worked by women and men hired workers in mung bean.

In both sites, women and men work from 7 am to 12 midday with a one- to two-hour lunch break. They then resume work from 2 pm to 5 pm or longer (women reported working 8 to 9 h a day on mung bean harvesting). Women’s daily wage in agriculture, regardless of crop or task, is 2.80 USD per day. Men receive 3.50 USD per day. For certain tasks, such as spraying, men earn up to 4.20 USD/day. When asked what they thought about the gender gap in wages, some women said that men work harder than women, but another said, “According to tradition, men get more wages than women, but there’s no reason for it and I cannot agree with it”.

In Village 1 women workers are hired for hand weeding and carrying water for foliar and pesticide application, which happens twice during the mung bean growing season. Spraying is normally done by men though a few women spray. Fieldwork provides women with about 10 to 15 days work a year. During manual harvesting in January through to February, women work 8 to 10 h per day for up to 30 days. Mung bean pods are not handpicked. Rather, the whole mung bean plant is uprooted, sundried and then mechanically threshed. Almost all women hired workers glean mung bean from the fields for around 15 days after the harvest. This involves collecting the fallen bean pods, threshing using a stick, sun drying, sieving for contaminants such as small stones and chaff, and selling directly to small buyers in the village. Some farmers allow hired workers to keep all the mung bean they glean whereas others request half of the product. If mung bean is manually harvested, each person can glean around 1.25 baskets (one basket is 32.7 kg–23.78 USD) over five days. This results in an income of 89.17 USD from 3.75 baskets for 15 days. Gleaning after manual harvesting provides high quality mung bean. However, mechanized harvesting is proving less favorable to gleaning. The quality is lower because mechanical harvesting can crush beans and pods, and also some beans are unripe. Each person can glean for around five days, and are only able to collect around one basket. This means women receive less money. In total, women in Village 1 work for 55 to 60 days per year on mung bean (30 days in manual harvesting). This suggests that women earn an average of 83.93 USD for manual harvesting, and the same again for other tasks. The income range is 83.93 USD to maximum 215.06 USD. The recent mechanization of mung bean harvesting has, however, removed a significant source of income for women. One woman explained how she is coping, “I have to pick wild vegetables and sell them, and I sell fish. Just yesterday I was diving in the irrigation canal for edible snails to sell”. It should be noted that though men can obtain work harvesting mung beans in nearby villages, this option is not open to married women due to their mobility constraints. As noted above they are expected to take care of children, other family members, livestock and to maintain the household in general.

Hired men in Village 1 are involved throughout the production cycle in mung bean harvesting, including land preparation using tractor and power tillers, cleaning the field (for men this means removing small bushes), broadcasting seed, foliar fertilizer application, herbicide spraying (men bring water themselves), pesticide spraying, inter-cultivation (weeding, hoeing), manual harvesting (though to a lesser extent than women) and threshing. Prior to mechanical threshing, men worked for 20 days threshing mung. Today, they work for just five days. In total, men work between 34 to 45 days on mung bean, with some men obtaining an additional twenty days per year if they follow the harvest elsewhere. Men can earn approximately 101.41 to 139.88 USD in mung bean harvesting (plus an additional 69.94 USD if they follow the harvest to local villages).

In Village 2 in the Central Dry Zone, women’s work in mung bean harvesting ranges from cleaning the fields (which for women means removing brash and crop residues from ploughed fields) and applying basal fertilizer and seeds into rows prepared by men, to harvesting and post-harvest operations. Harvesting involves handpicking mung bean and is conducted two to three times. During the third harvest, some farmers hire workers to uproot harvested mung bean plants (i.e., residue) for cattle fodder (a very few hired respondents both have cattle and use residue as fodder). There is no gleaning. Women are engaged for between 44–68 days per mung bean season and earn 2.80 USD/day (123.09–190.24 USD). Of this, 10 to 15 days are in harvesting (27.98–41.96 USD). Men have around 30 to 40 days work per mung bean season and receive 3.50 USD/day (104.91–139.88 USD).

In Villages 3 and 4 in Bangladesh, women rarely engage in field activities associated with mung beans. However, harvesting mung bean is considered a woman’s task, though a very few men—the most poor—also pick mung bean. Working hours are the same for both genders. The day starts at 7 am with breakfast at 9 am for 20 min. Lunch is from 2–3 pm. Workers finish between 5 pm and 6 pm. Men and women workers are paid the same piece rate per kilo instead of a fixed daily wage.

In Village 3, women pick pods for 30 days. They also have another 10 to 15 days in post-harvest operations. The piece rate varies by harvest. For the first picking, women are paid 0.12 USD/kg. For the second picking, they receive 0.14 USD/kg and for the third picking, 0.18 USD/kg. There is a fourth picking where hired workers share 50% of the crop with the smallholder. On average, women pick 15 kg of mung bean per day. This gives nominal figures across the season of 1.78 USD/day; 2.13 USD/day and 2.66 USD/day. Post-harvest operations include grading mung bean for five days, winnowing for three days, drying for three days and threshing for four days (this is about 15 days but the days required vary between 10 to 15 days). They are paid about 2.37 USD/day. It is rare for hired workers to glean though farmers invite widows and elderly people to do so. In total women obtain 30 days harvesting mung bean, and about 10 to 15 days on post-harvest operations (40–45 days a year), thus earning between 71.04 and 106.57 USD in total.

Men in Village 3 are engaged in all field tasks for mung bean. This includes land preparation, weeding and spraying. For most tasks, men are paid an average daily wage of 2.96 USD for a half day (7 am to 1 pm). For specific tasks men are paid piece rates (0.59 USD for 0.13 ha of land), for example for spraying pesticides. In total, men work for around 40–45 days in mung bean (excluding harvesting and post-harvest processing), earning between 118.41 to 133.21 USD. As mentioned, only the poorest men harvest mung bean. Whereas one wealthy farmer contemptuously described men harvesting mung bean as ‘weak’ and claimed it is not a man’s job, a landless laborer described how he works every day as a hired laborer—mostly in sugar cane—from 6 am to 1 pm (seven hours). Meanwhile, his wife tends their two dairy cows and takes care of their child and household. They eat together and rest and then—in the mung bean season—both harvest mung bean together—as hired labor—from 3 pm to 7 pm or until darkness falls. This equates to at least an 11-h day for the male hired laborer, and the woman works a similarly long day. It is hard to consider such a man ‘weak’ and the remark by the wealthy farmer suggests a gap in understanding of the reality of people’s lives between community members.

In Village 4, women work for an average of 30 days on manual harvesting. A few women glean mung bean for home consumption (2 to 3 kg of mung bean from 0.4 ha). Women thus obtain between 40 to 45 days a year of work on mung bean on harvest and post-harvest operations and they earn between 125.51 and 137.35 USD. As in Village 3, men work across a range of tasks during the growing season. They obtain 45 to 55 days of work on mung beans. The average male wage is 4.74 to 5.92 USD per day. Across the mung bean season men earn 239.78 to 293.06 USD. Men laborers also collect residues for their livestock, for free, and give them to their wives to feed livestock (nominal market value of residue 5.92 to 8.23 USD from 0.13 ha).

Taken together, the findings show that for women in all study sites mung bean is an important source of income. Women in Village 1 in Myanmar work for around two months on mung bean, one in field operations and one on harvesting alone, and earn between 83.93 USD to 215.06 USD in total. In Village 2, women work between 1.5 to just over 2 months on this crop with about 0.5 months in harvesting (123.09–190.24 USD). In Bangladesh, women earn money from harvesting and postharvest operations. In Village 3, this accounts for around 1.5 month’s work (71.04–106.57 USD) and in Village 4 women likewise work 1.5 months and earn 125.51 USD to 137.35 USD. Mung bean harvesting is one of the only sources of income for women in Villages 1, 3 and 4 and provides women with a significant opportunity to contribute to the household budget.

3.2.2. Research Question 2: Are Women Workers Likely to Be Able to Innovate into Alternative Sources of Income?

The data above suggest that women, and men to a lesser extent, will face a significant loss of income if mung bean harvesting is mechanized. This will also reduce income from post-harvest processing and gleaning. We therefore investigate whether women and men are likely to innovate into alternative livelihood activities. To do this, we discussed gender norms across the research tools and how they relate to the ability of women, and men, to innovate. In FGD 4, we asked: What characteristics help women, or men, to succeed in a new enterprise? Which factors promote, or hamper women and men who want to innovate?

In Myanmar, respondents in Village 1 argued that women and men innovators share some characteristics. They need to be willing to work hard, be creative, have good management skills and have access to sufficient funds. The characteristics ascribed specifically to women innovators, however, are deeply influenced by assumptions around their gender roles. As noted above, almost all our women respondents were married with families and are considered primary carers. Therefore, it was argued that women must be good at allocating time between their business, care and household activities. Critically, women need the support of their spouse and wider family to innovate. Men also need the support and trust of their family, but this is less of a deal-breaker than for women. Men are more likely to be innovators because men are already associated with decision-making over large sums of money, whereas women—though they hold the household budget—are able to make independent decisions only over small sums. Women had few ideas when asked how they could respond to mechanization of mung bean harvesting. They suggested opening pharmacies or grocery shops, buying land and livestock. However, in general they argued that the village is simply too small to accommodate many businesses, and well-educated women—“we have so many graduates”—also find it almost impossible to find work. One woman (Village 1) explained, “Some young women can out-migrate, but we all have children, and have to care for them. We don’t have any networks to help us migrate, and we cannot take our families if we don’t know where we can sleep. We are scared to do that”.

In Village 2, respondents claimed that women are usually less innovative than men. However, this is slowly changing because young, educated women want to do things differently. Furthermore, training courses in leadership and communication skills are encouraging women to participate in different activities. Men who are good leaders and communicators, and who are knowledgeable, always seek to innovate. Respondents argued that women and men need technical support, training, sufficient money and motivation to do new things. However, even if women have these things, norms which frame men rather than women as innovators continue to pose a significant barrier to women’s ability to do new things. For example, respondents argued that women have the capacity to use machinery since modern machinery is considered easy to handle. However, most women said they are afraid of machines and do not trust themselves with them. They feel that handling, managing and repairing machinery is a man’s job.

In Bangladesh, respondents in Village 3 thought that young, intelligent, educated women who are eager and courageous may be able to change their situation. A few women have innovated in terms of technology, for example by using electric fans rather than bamboo sticks to winnow some crops. However, women respondents working in mung bean harvesting—who, as in Myanmar, are mostly married with children—said that innovation was difficult due to a lack of family support, insufficient money, lack of local government/NGO support and criticism from the community. Men respondents commented that, “It‘s really tough to be a woman innovator. In our society a woman cannot do anything alone, she needs permission from the family to go outside or to do anything”.

Gender norms expressed by some men respondents in Bangladesh suggest that women should prioritize their household and care work and focus on raising livestock. Women who leave their homes can face abuse from community members. However, practice can be different. An important innovation in Village 3 is that more women have started working in the fields over the past five years or so. This is largely a consequence of the rapid increase in agricultural productivity in the past decade, reported above. More labor is required, yet men’s labor is insufficient. This is partly because men are mobile and can pursue more lucrative opportunities elsewhere, but also because some wealthier men refuse to work in agriculture. Beyond this, increased education and social awareness are seen as contributing causes to women’s ability to earn money outside the home. A community profile respondent (man, Village 3) indicated that in the past “society did not accept women working in the fields, nowadays, it’s accepted as a job. She’s earning for her family”.. A hired woman in the same community said, ‘Society honors women who work as hired agricultural labor. They respect us. They know we are working for the family. If you can give a contribution it raises your prestige. People look at you in a different way”. This contributes to the community level empowerment of poor women. “Even poorer women are now able to go to the Union Parishad and raise their issues and expect to be listened to. Her issues are taken seriously” (Community profile respondent, man). When asked what they would do if mung bean harvesting was mechanized, women rapidly listed some ideas, such as embroidery and making quilts. However, as in Myanmar, women would need support in developing such cottage industries, and in particular in selecting competitive businesses.

In Villages 3 and 4, social norms permit men to freely pursue their interests. Male respondents in Village 3 commented that “Men have enormous power and liberty to do what they want. We don’t need to think about social limitations. So, we have the maximum possibility to innovate”. Men are under no obligation to consult with their wives. Even so, several men said they “discuss everything with my wife”. Although men, as in Myanmar, tend to make key decisions around large assets, poor men do not have such assets. A lack of capital, land and lack of local political support often hinder poor men from doing things differently. One man said, “Our life is painful. You cannot understand it. It is difficult to earn money by selling your labor in the fields. Poor people like us live hand to mouth”.

3.2.3. Research Question 3. How might this Change in Income Affect the Economic and Personal Empowerment of Women Workers?

In the introduction, we said we were interested in whether the loss of income from mechanizing mung bean harvesting could hamper the ability of women to make a meaningful life. Our data shows that for women, their ability to contribute to their family’s needs, develop a sense of self-esteem and develop a sense of renewing cultural identity are all important to them.

In both countries women’s visible participation in fieldwork and in providing income to their families earns them respect from their families and from the wider community. In Myanmar, the normative assumption is that women need to engage in paid work. Their earnings are important to meet household needs. Today, no household can depend only on a man’s income. Women’s economic contributions are noticed and valued in the household and in the community. Whilst a few women respondents in Village 1 said that mung bean was not key to their family’s livelihoods, other women said it was very important. “It is my main source of income”, and “Income from mung bean is higher than selling fish and vegetables”. The data shows that income from mung bean forms 50–100% of a woman’s earnings in this community. The money is spent on all household needs including food, clothes, school fees, livestock inputs, social occasions, health and more.

Whereas in the past in Bangladesh women working in the fields were considered to be of exceptionally low status, all the hired women respondents we met were proud of their work in harvesting mung bean. Their financial contribution is valued by their husbands and recognized as important by many others in the community. Women would certainly swop fieldwork for easier work should it exist—but the income they currently earn from fieldwork is vital to their sense of self-esteem. It is important to their household’s functioning, too, with women and men agreeing that women’s income is critical to the education of their children. One man (Village 3) confirmed that his wife’s income from mung bean covered one month of their outgoings and added, “We cannot run the family without my wife’s income”. Women use their income to keep their children in school and into college. Children recognize their mother’s efforts and “see it as important”. One woman (Village 3) commented “My children are my dream and my life. I invest my income and my life in both of them. I pray they won’t be like me. They’ll create a position for themselves in society”.

Turning to the renewal of cultural identities, in Myanmar it became clear that the importance to respondents of being able to engage in various Buddhist ceremonies and community works cannot be underestimated. They wanted to participate in donation ceremonies (which includes providing food to the local monastery) and more generally through ‘good deeds,’ which includes providing free labor to community works. These issues were raised by respondents because such deeds help towards effective reincarnation, as well as contribute to village development and thus build good social capital. However, hired workers generally do not have enough time for such works, though they do contribute annually to road repair. Hired women (Village 1) reported that “We try hard to contribute to the wellbeing of the community, but we have little time and leisure to relax. We only have an average of 15 days income per month and the other days we are always busy in mind trying to find work and money”. Another added that “We can’t give money or food, but we can donate our time. We contribute physical labor. Every year the roads have to be rebuilt after the floods in September or October so we help for free”.

In Bangladesh, respondents face similar issues in relation to their ability to contribute effectively to community needs and causes. Since men have much higher mobility, this was particularly an issue for male hired laborers. As in Myanmar, men contribute labor rather than money to local causes. This may include road maintenance, water switch gate operating and helping to build mosques.

4. Discussion

The research hypothesis of this article is that the (potential) impacts of mechanizing mung bean harvesting are likely to weaken women hired workers’ economic and personal empowerment. The data broadly confirm the hypothesis.

However, there are likely to be differences in impact within and between Myanmar and Bangladesh. Mechanization is an inevitable process, and will remove an important source of income for women, and to a lesser extent men laborers. In our two Bangladesh research sites, harvesting mung bean is the only fieldwork task open to nearly all of the landless women we met. They are otherwise restricted to engaging in time-consuming cottage industries with low profit margins, or working unpaid on the family farm and in the home. In Myanmar, in Village 1 women earn between 50% to 100% of their annual agricultural income from mung bean and 20%–28% of this is from harvesting and post-harvest processing. In contrast, the impacts may be less serious in Village 2 as women may experience around 10% loss of income.

Will women be able to substitute this income? The evidence unsurprisingly suggests that the impact of mechanizing mung bean harvesting is likely to differ according to the relative degree of alternative on- and off-farm income generating opportunities available locally and nationally. Village 1 in Myanmar experiences low on-and-off-farm economic diversity. Gender norms mean that men are far more likely to find work in local off-farm industries and services than women, particularly married women with families—who form the bulk of hired laborers. In Village 2, though, women are, potentially at least, more likely to be able to find alternative sources of income. The site benefits from broader on-farm crop and livestock diversity than Village 1, and a much wider range of potential income-generation opportunities locally. Over 70% of women have already moved out of agriculture and gender norms are shifting to accommodate this. Even so, married women may find it harder than their daughters or single peers to find other forms of income.

Our data indicate that a dynamic economic environment per se is insufficient to allow women to take up alternative opportunities. The literature review noted that typical local off-farm opportunities, such as construction and carpentry, tend to benefit men in Myanmar due to the gendered construction of labor. In Bangladesh, the gendered construction of local labor opportunities is more constrained still, with the added constraint that women’s mobility—which is part of a broader set of patriarchal concepts around women’s roles and what they should be and do—is severely restricted. Furthermore, women we met in both countries are primarily mothers, charged with household and care work, and this is another factor that contributes to their lack of mobility. This means that women in both countries, with few assets of their own, are largely confined to seeking, or building, economic opportunities within their own communities. This is a challenging task. In Bangladesh, opportunities for women in off-farm work appear to be stagnating after a period of sustained growth, and women are mainly concentrated in low-paid insecure jobs rather than moving into white collar jobs [42].

What would a loss of income mean for the women respondents? A lower contribution to household income may reduce their voice in intra-household decision-making. The important support that women in the Bangladesh sites can provide to their children to enable them to stay at secondary school, and into tertiary education, may no longer function. Gender norms around “what is possible” for women may potentially become more rather than less restrictive as women are pulled out of the field. In locations such as Village 2 in Myanmar, where women are already pushing the envelope, and where alternative employment exists for many, mechanization may simply speed up the pace of change. Even so, it is probable that not all women will have the skills, time or capacity to adapt (otherwise they most probably would have moved out of mung bean harvesting already). Overall, men across all sites will be less affected since their participation rates in harvesting and post-harvest processing are low. Also, men are less restricted by gender norms and can travel freely to find work elsewhere. This said, the women and men respondents to this study have an extremely low asset base and they have, up to now, lacked the resources to invest in alternative forms of income generation, including outmigration. In all four study sites, women find it harder to innovate than men. Men rather than women are framed as innovators, and so it is simpler for men to accrue family and community level support, and financial resources to innovate.

Income is not the only proxy for empowerment. The human development approach, measured in the Human Development Reports, considers the object of development to be about expanding the capabilities of individual women and men to define and live the lives they want to have. In this shift from desire to realization, people move from having a potential of being, and doing, into actually being able to be, or to do [44]. Our data suggest that respondents make clear associations between doing, and being, and income. Women shared ways in which their income benefited their families, for example in Bangladesh through supporting their children’s education. They also shared ways in which their lack of income hampered their ability to participate effectively in community level practices, including religious observance. Research conducted in Cambodia [45] showed that rather than seeking personal autonomy, women see empowerment as an outcome of contributing to, and gaining respect from, others, including partners, the wider family and the community. Our findings echo this understanding.

Moving Forward

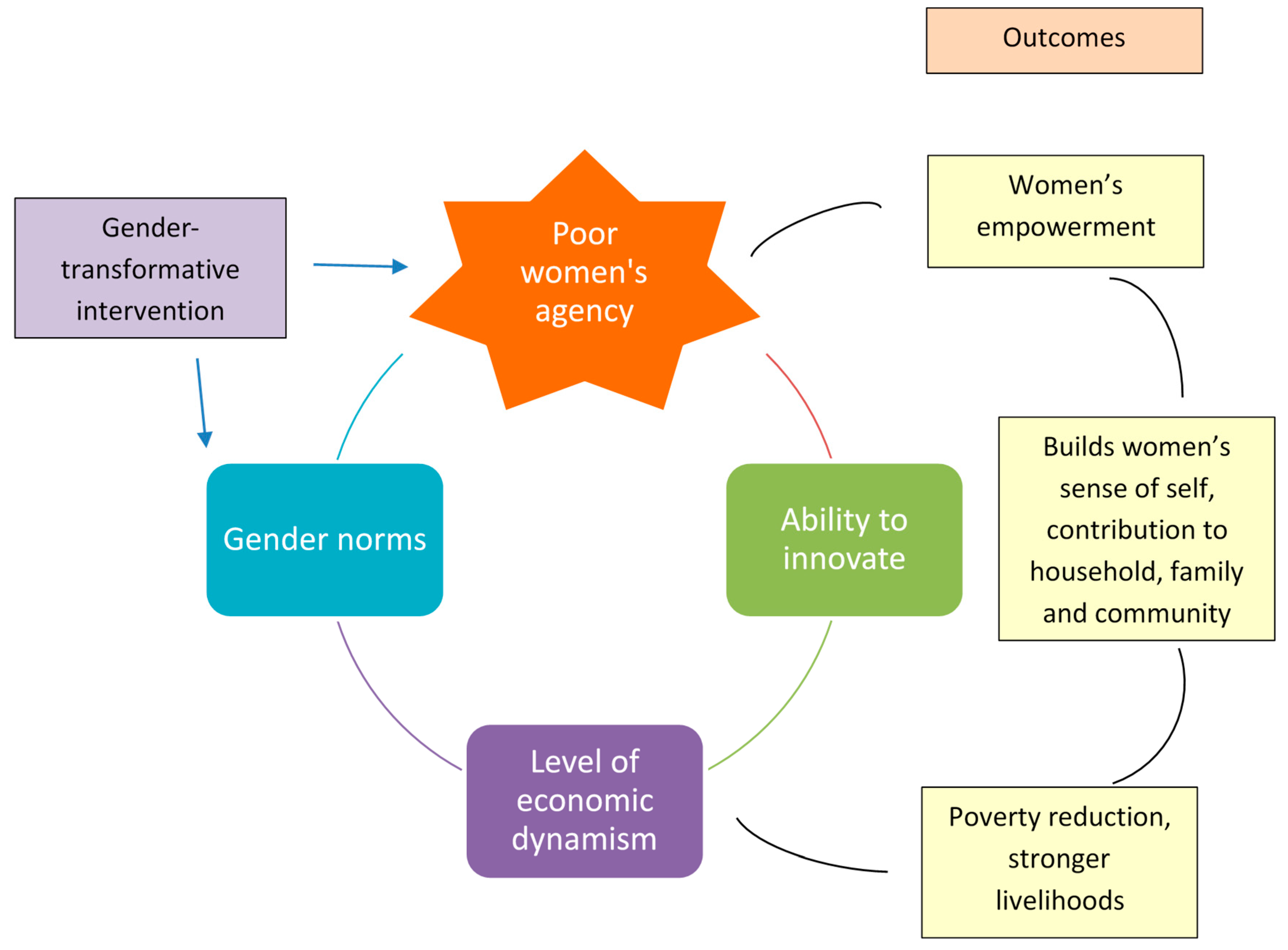

The dilemma explored in this article is the fact that mechanization of mung bean harvesting, which is inevitable because it reduces farmers’ costs and increases profits, may well do harm to potentially hundreds of thousands of women laborers who rely on harvesting mung bean for an important part of their income. Given this scenario, development actors need to take mitigating action. Investing in women’s capacity, helping them to develop small and medium-scale enterprises (SMEs), and assisting them in entering new forms of work is important. However, such activities do not challenge the underlying issue constraining women’s ability to take charge of their destinies. This is that gender norms strongly determine appropriate behaviors for women and underpin local assumptions of which work is considered suitable for each gender. One way forward is to invest in gender transformative approaches [46,47]. These aim to stimulate change in norms and associated behaviors to make a wider range of choices possible. Gender transformative approaches target gender relations rather than women, or men [48,49,50], to facilitate transformation. They aim to ensure that men as much as women benefit from transformation, and to ensure that the whole community sees the benefits. We show how this could happen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Strengthening women’s agency. Source: Partly based on [15].

Figure 1 sees promoting women’s agency (the spark) as key to moving forward. Without strengthening women’s agency, and thus their power as actors, women will not be able to innovate and do things differently. Moving anti-clockwise, it suggests that gender transformative approaches also need to work on gender norms because they limit the scope of what women can be and do. Changing gender norms and strengthening women’s agency is contingent upon men’s buy in, and in particular, that men do not see women’s empowerment as a zero-sum game [51,52]. This is why gender transformative approaches prioritize working with women and men together, and the wider community, to secure change. At the bottom of Figure 1, we suggest that changes in gender norms can be facilitated by a dynamic economy, but the economy per se does not define what is possible for women to be and to do. We have already shown that norms can preclude women from actively engaging in various economic activities. The economy provides opportunities which can be better taken advantage of by women and men who possess the capacity to innovate. Moving upwards, we suggest that participation in the economy in turn can promote women’s agency in a dynamic process of change. Turning to outcomes, we suggest that effective implementation of gender transformative approaches, alongside more traditional interventions to develop the economy and help build skills, capacity and assets, women may become empowered both personally and economically. This could strengthen their sense of self, and their ability to contribute to their families and community, and to get this recognized. Empowerment is a goal in itself, but women’s empowerment may also facilitate other beneficial development impacts.

5. Conclusions

The mechanization of farm operations is arguably inevitable as farmers adopt technologies that reduce their input costs. It is a gradual and cumulative process that happens at different speeds at different locations. In Myanmar and Bangladesh, the adoption of mechanization in mung bean harvesting is likely to displace labor supplied by landless households. This is very likely to accentuate socio-economic disparities between community members—between farmers who can, and cannot mechanize, and between farmers and landless people. The displacement of labor will probably have disparate effects on women and men hired laborers as well. Women, particularly married women in landless households, are likely to lose an important source of income. Men will be less affected as they derive less income from mung bean harvesting, have more opportunities for off-farm work, and are more mobile to seek employment elsewhere. However, the loss of women’s income in the household budget may place stresses on men to earn more, and in general negatively impact on the well-being of the whole family. This may have intergenerational effects if children are pulled out of school or do not move into higher education. Mechanization thus forces a harsh tradeoff between the social and economic sustainability of farmer livelihoods, and the social and economic sustainability of the livelihoods of hired workers, and it has particularly harsh potential implications for women hired workers.

Whilst government agencies are promoting the adoption of mechanization of agriculture in Myanmar and Bangladesh with the aim of stimulating agricultural growth, it is important that such initiatives are accompanied by socio-economic programs that attempt to mitigate potential impacts on landless households and particularly women in such households. Such programs need to adopt gender transformative approaches to stimulate change in norms and associated behaviors, among more conventional investments in the economy, to make a wider range of choices possible.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R.F.; methodology, C.R.F., L.D., T.M., R.M.N., P.S., A.M.S.; investigation, C.R.F., A.M.S., R.J., N.D.K., T.M., L.D.; formal analysis, C.R.F., A.M.S., M.M.I., N.D.K., L.D.; writing–original draft preparation, C.R.F., A.M.S., M.M.I., N.D.K., L.D.; writing—review and edition as previous and P.S., R.M.N., T.M., R.J.; visualization, C.R.F., A.M.S., L.D., M.M.I., N.D.K.; supervision, P.S., R.M.N.; project administration, L.D., P.S.; funding acquisition, R.M.N., P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) under the project “Improved Mung bean Harvesting and Seed Production Systems for Bangladesh, Myanmar and Pakistan” and other long-term strategic donors to the World Vegetable Center: Taiwan, UK aid from the UK government, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Germany, Thailand, Philippines, Korea, and Japan.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all the hired workers, and other informants, in Myanmar and Bangladesh. They spent a huge amount of time with us, patiently answering our questions and adding so much more. We would also like to thank the local extension services for arranging the fieldwork in both countries. We thank AKM Mahbubul Alam of the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI) for his administration of the project in Bangladesh and we thank Abdur Rashid of BARI and Mohammad Mizanul Haque Kazal of Sher-e-Bangla University and his team for their contribution to the qualitative research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Rigg, J.; Salamanca, A.; Thompson, E.C. The puzzle of East and Southeast Asia’s persistent smallholder. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 43, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottaleb, K.A.; Krupnik, T.J.; Erenstein, O. Factors associated with small-scale agricultural machinery adoption in Bangladesh: Census findings. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 46, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phyo, A.S.; Grunbuhel, C.M.; Williams, L.; Htway, S.S. Does selective mechanisation make up for labour shortages in rural Myanmar? IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 338, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theis, S.; Krupnik, T.J.; Sultana, N.; Rahman, S.-U.; Seymour, G.; Abedin, N. Gender and Agricultural Mechanization: A Mixed-Methods Exploration of the Impacts of Multi-Crop Reaper-Harvester Service Provision in Bangladesh; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Volume 1837. [Google Scholar]

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Yearbook of Agricultural Statistics-2019; Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2020.

- Central Statistical Organization. Myanmar Statistical Yearbook 2018; Central Statistical Organization: Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar, 2018.

- Barton, L.; Thamo, T.; Engelbrecht, D.; Biswas, W.K. Does growing grain legumes or applying lime cost effectively lower greenhouse gas emissions from wheat production in a semi-arid climate? J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 83, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Lam, H.-M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Varshney, R.K.; Colmer, T.D.; Cowling, W.; Bramley, H.; Mori, T.A.; Hodgson, J.M.; et al. Neglecting legumes has compromised human health and sustainable food production. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 16112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Clark, M.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Wiebe, K.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Lassaletta, L.; de Vries, W.; Vermeulen, S.J.; Herrero, M.; Carlson, K.M.; et al. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature 2018, 562, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreinemachers, P.; Sequeros, T.; Rani, S.; Rashid, M.A.; Gowdru, N.V.; Rahman, M.S.; Ahmed, M.R.; Nair, R.M. Counting the beans: Quantifying the adoption of improved mungbean varieties in South Asia and Myanmar. Food Secur. 2019, 11, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Schreinemachers, P.; Shah, H. An Exploration of the Gendered Effects of Mechanical Mungbean Harvesting in Pakistan. Gomal Univ. J. Res. 2019, 35, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Faxon, H.O. Securing meaningful life: Women’s work and land rights in rural Myanmar. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 76, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M.C.; Sen, A. The Quality of Life; Clarendon Press and Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1993; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Badstue, L.; Elias, M.; Kommerell, V.; Petesch, P.; Prain, G.; Pyburn, R.; Umantseva, A. Making room for manoeuvre: Addressing gender norms to strengthen the enabling environment for agricultural innovation. Dev. Pract. 2020, 30, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantor, P. Transforming Gender Relations: Key to Positive Development Outcomes in Aquatic Agricultural Systems; WorldFish: Penang, Malaysia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Badstue, L.; Lopez, D.E.; Umantseva, A.; Williams, G.; Elias, M.; Farnworth, C.R.; Rietveld, A.M.; Njuguna-Mungai, E.; Luis, J.; Najjar, D. What drives capacity to innovate? Insights from women and men small-scale farmers in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. J. Gend. Agric. Food Secur. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, T.R.; Pingali, P.L. Do agricultural technologies help or hurt poor farm women? In Competition and Conflict in Asian Agricultural Resources Management: Issues, Options, and Analytical Paradigms; IRRI: Los Banos, Laguna, 1996; pp. 237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Rathgeber, E.M. Rural Women’s Access to Science and Technology in the Context of Natural Resource Management. In Proceedings of the Expert Group Meeting “Enabling Rural Women’s Economic Empowerment: Institutions, Opportunities and Participation”, Accra, Ghana, 20–23 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rigg, J.; Salamanca, A. Aggregate trends, particular stories: Tracking and explaining evolving rural livelihoods in Southeast Asia. In Routledge Handbook of Southeast Asian Development; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, T.R.; Chi, T.T.N. The Impact of Row Seeder Technology on Women Labor: A Case Study in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2005, 9, 157–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, A. Technical Change and Gender Wage Inequality: Long-Run Effects of India’s Green Revolution. SSRN 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risseeuw, C. Bourdieu, power and resistance: Gender transformation in Sri Lanka. In Masters of Modern Social Thought: Pierre Bourdieu; Robins, D., Ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK; New Delhi, India, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Petesch, P.; Badstue, L.; Camfield, L.; Feldman, S.; Prain, G.; Kantor, P. Qualitative, comparative, and collaborative research at large scale: The GENNOVATE field methodology. J. Gend. Agric. Food Secur. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigg, J. More Than the Soil: Rural Change in SE Asia; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Farnworth, C.R.; Jafry, T.; Lama, K.; Nepali, S.C.; Badstue, L.B. From Working in the Wheat Field to Managing Wheat: Women Innovators in Nepal. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2019, 31, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, I.; Lahiri-Dutt, K.; Lockie, S.; Pritchard, B. The feminization of agriculture or the feminization of agrarian distress? Tracking the trajectory of women in agriculture in India. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2018, 23, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnworth, C.R.; Jafry, T.; Rahman, S.; Badstue, L.B. Leaving no one behind: How women seize control of wheat–maize technologies in Bangladesh. Can. J. Dev. Stud. Rev. Can. D’études Dév. 2020, 41, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartaula, H.N.; Visser, L.; Niehof, A. Socio-Cultural Dispositions and Wellbeing of the Women Left Behind: A Case of Migrant Households in Nepal. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 108, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnworth, C.R.; Jafry, T.; Bharati, P.; Badstue, L.; Yadav, A. From Working in the Fields to Taking Control. Towards a Typology of Women’s Decision-Making in Wheat in India. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belton, B.; Filipski, M. Rural transformation in central Myanmar: By how much, and for whom? J. Rural Stud. 2019, 67, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Gao, Q.; Li, X. The Impact of Rural-urban Migration on Gender Relations in Chinese Households. Asian J. Women’s Stud. 2013, 19, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, M.T.; Thinzar, A.M.; Zu, A.M. Supply Side Evidence of Myanmar’s Growing Agricultural Mechanization Market; Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics, Michigan State University, Justin S. Morrill Hall of Agriculture: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki, T. Labor contracts, incentives, and food security in rural Myanmar. In Hi-Stat Discussion Paper Series; Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University: Olsztyn, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boutry, M.; Allaverdian, C.; Mellac, M.; Huard, S.; Thein, S.; Win, T.M.; Sone, K. Land Tenure in Rural Lowland Myanmar: From Historical Perspectives to Contemporary Realities in the Dry Zone and the Delta; Gret: Yangon, Myanmar, 2017. [Google Scholar]