Abstract

Over the past decade, transit-oriented development (TOD) has been advocated as an applicable urban regeneration planning model to promote the sustainability of cities along with city dwellers’ standards of urban living. On a regional scale, under the directives of the Qatar National Vision 2030 (QNV-2030), the Qatar National Development Framework (QNDF-2032), and the strategies for planned mega events, such as the FIFA World Cup 2022, the State of Qatar launched the construction of the Doha Metro, which consists of four lines. This transport system, linking the center of Doha to several transit villages around approximately 100 metro stations, aims at reducing the number of vehicles on the road networks while providing an integrated transportation and land use strategy through the urban regeneration of transit-oriented developments (TODs), providing both social and environmental economic benefits. Among the most significant transit sites within the Doha Metro lines is the Souq Waqif station. This station is a historical–heritage spot that represents a potential socio-cultural site for the creation of a distinctive urban environment. This research study investigates an approach suitable for an urban regeneration planning scheme for the Souq Waqif TOD, aiming at (i) preserving and consolidating the deeply rooted cultural heritage of the historical site and (ii) enhancing the city dwellers’ and/or the community’s standards of urban living. This study aims to explore the applicability of a TOD planning scheme for the new metro station through urban regeneration and land infill in the existing built environment of the Souq. This study contends that the efficient integration of land use with transport systems contributes to shaping an environment with enhanced standards of living for users while supporting social, economic, and environmental factors. The present research design comprises qualitative data based on theoretical studies and site-based analysis to assess (i) the principles of TODs and (ii) the extent to which their application can be employed for the Souq Waqif to become a sustainable TOD.

1. Introduction

While the worldwide population of urban areas is increasing, few regions are facing urban growth as fast as that in the Middle East and the Arabian Gulf region. For this reason, the rapid development of the Gulf countries, in contrast to Western cities, is described as “instant” growth. In this region, the State of Qatar has witnessed vast and rapid urban growth in the past two decades. The population of Doha, the capital city, increased from below 500,000 to 1.2 million since the year 2000 and is expected to continue to grow [1]. Additionally, as envisioned through the Qatar National Vision 2030, Qatar initiated the construction of various mega projects and facilities, such as metro lines, airports, ports, parks, and stadiums for the upcoming 2022 FIFA World Cup [2,3]. In turn, this intense instant urban and population growth phase has caused serious environmental, economic, and social problems, such as (i) traffic congestion, (ii) environmental pollution, (iii) fragmentation of the urban fabric, and (iv) other ecological and social threats.

Instant urban and population growth contribute to urban sprawl. The sprawling and fragmentation of urban areas cause overdependence on automobiles as the preferred mode of transportation. Scholars argue that the extensive use of private vehicles, which facilitate personal mobility and provide a sensation of security, territoriality, and heightened status, cannot be a sustainable means of transport. Such vehicles represent a menace to city dwellers’ standards of urban living [4,5]. Consequently, scholars and planners in urban design have concurred that the most logical approach to tackle the detrimental effects derived from the excessive use of private vehicles is through interdisciplinary urban regeneration planning schemes. Such schemes aim at integrating land use and multimodal transport systems around compact, mixed-use transit villages located around stations. This model is also defined as “transit-oriented development” (TOD) [6,7,8].

In the case of Qatar, residents’ dependence on the use of private vehicles has been justified by the lack of alternative modes of transportation to connect the fragmented urban districts and provide an effective solution to urban sprawl. Therefore, in response to the drastic increase in traffic congestion and automobiles, the state of Qatar is currently constructing the new Doha Metro project, which includes approximately 100 metro stations along its four main lines.

Doha Metro, along with these stations, will facilitate the creation and urban regeneration of TODs along the metro rail corridors, thereby enhancing the region’s vision for smart growth and sustainable developments by creating vibrant, walkable, and livable neighborhoods.

In this study, we focus on the heritage site of the Souq Waqif (or the local market). Souq Waqif is an old market that underwent renovations in 2006 to conserve its traditional architectural style. The Souq is strategically located in the heart of Doha, adjacent to Msheireb Downtown Doha to the west, Al Bidda Park to the north, and the Corniche waterfront promenade to the northwest. There are limited bus stations and underground car-parking locations that serve the Souq’s daily visitors, in addition to two stations of the future Gold Metro line. Such facts add to the site’s significance as a historical–heritage transit village located along the Doha Metro. Therefore, this study investigates a suitable urban regeneration planning scheme for the investigated Souq Waqif TOD, aiming at (i) preserving and consolidating the deeply rooted cultural heritage of the historical site and (ii) enhancing city dwellers’ standards of urban living.

The objective of this research is twofold. Firstly, we assess the potential of the selected site, namely Souq Waqif, for adaptive transformation as a transit village in a historical–heritage urban node. Secondly, based on this assessment, we provide an applicable urban regeneration planning scheme to contribute to the urban quality of life in the district. Thus, the aim is to foresee the contextualized adapted urban development as a future model for enhancing the long-term health and sustainability of Souq Waqif, while also being applicable to other heritage sites in Qatar.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The TOD as a Model for Sustainable Urban Regeneration

The detrimental effects derived from non-sustainable urban growth over the past decades have prompted municipalities, practitioners, and researchers to implement strategies for the urban regeneration of the built environment of our cities and thus diminish harmful social, economic, and environmental threats. In turn, recent urban regeneration planning schemes have been envisioned with “sustainability” as the leading concept to address and manage the enhancement of social well-being and economic prosperity as much as environmental care, or simply to promote sustainable urbanism [9,10,11,12].

Sustainability and urbanism became popular as global challenges in response to 1987’s Brundtland report, which highlighted, through a thorough body of research, how the conditions of the planet’s ecosystems are degrading due to global-scale human economic activity. This environmental degradation is worsening the majority of people’s quality of life. As a result, the report stressed that the growing human impacts on non-human environments cannot be sustainable and that societies must embrace “environmentally sustainable developments”. It is a challenge to ensure equal opportunities for future generations based on the current triple bottom line model; economic development policies and practices must be balanced with equal care for environmental and social impacts.

In the 21st century, the practice of urban regeneration occupies an increasingly significant role as a mechanism for leading and managing “environmentally sustainable developments”, requiring urban planners and architects to confront the metropolitan growth that occurred in the past century without effective consideration of the threats, constraints, and pressures of rapid population growth, urbanization and intensification, resource consumption, and climate change. Despite urban regeneration being a widely experienced phenomenon, there is no single theoretical explanation or physical model that can be adopted to address all urban problems and/or provide effective solutions. Therefore, effective and lasting urban regeneration intervention must comprehensively consider local circumstances.

Furthermore, since greenfield housing development continues to be the low-density dominant mode of urban expansion, a consistent challenge for urban planners and architects is the containment of urban sprawl, which is considered a major problem. Therefore, practitioners are targeting “infill” housing development—houses built on previously developed land—in an attempt to redirect population and housing investments inwards to avoid urban sprawl from occurring on greenfield sites in the outer suburbs.

At the same time, urban regeneration projects extend beyond an individual or a group of buildings. They also incorporate the re-creation or regeneration of precincts and/or activity centers, comprising parcels of properties and the associated public realm and urban infrastructure. Activity centers are associated with concentrations of residential, retail, commercial, and leisure activities at levels ranging from the central business district (CBD) scale to peripheral villages. This spatial configuration responds to the need to minimize the travel times of the resident population within the central activity node (the poly-centered city–city of cities—the “20 min city”) to diminish the use of private vehicles. The focus is on intensified mixed-use development, integrated with multimodal transport systems such as trains, buses, taxis, walking, cycling, and others. This model is what defines transit-oriented development or TOD as an activity center: a clustered mixture of land uses and housing at a higher density alongside public spaces around high-quality public transport services configured as the core of the enlarged community. TOD is envisioned as a sustainable development model in response to the updated environmental and ecological debate on the contemporary global challenge of climate change [13,14,15].

A TOD is a compact pedestrian-friendly settlement serving a set of compact mixed uses that can be conveniently traversable on foot while also being served by public transport. Calthorpe defined three key criteria known by their initials as the “three Ds”: (i) density, (ii) diversity of land use, and (iii) design of urban spaces. The three Ds are critical for successful metropolitan developments around transit stations. In addition, Ewing Cervero (2010) and other researchers identified another “three Ds,” which are (iv) distance to transit, (v) destination accessibility, and (vi) demand management [4,11,16]. The TOD model has increasingly been adopted for the regeneration of urban communities, promoting higher standards of urban living and representing a tool for reducing uncontrolled urban sprawl, traffic congestion, and urban fragmentation. Moreover, the TOD model creates compact and mixed-use eco-communities that are both walkable and well-served by public transportation.

Significantly, TOD leads to the resilient, adaptive creation of communities based on flexibility for targeting ever-changing demographic, environmental, and socio-economical challenges [17]. Adaptive communities ensure that both individual and community development can be pursued, following the “place” methodology that advocates proactive planning and an interdisciplinary approach based on community consensus [18,19]. Enriching existing land use plans and evaluation methods by incorporating a transit accessibility measure is a popular tool in the process of place making [20,21,22]. The concept of adaptive communities is intertwined with TOD, defined as settlements of a central rail or bus hub bordered by high-density and mixed-use development [23]. TOD settlements prioritize connectivity, walkability, street attractiveness, parking management, adequate facilities, and socio-economic capital, integrated in a comprehensive urban design scheme [24].

Historically, the TOD model has evolved by responding to low-density and sprawling development, which still facilitates its contribution as a workable tool in the process of the smart growth and sustainable urbanism of cities in the 21st century. When a comprehensive land-use planning scheme is provided, TOD can significantly contribute to the (i) sustainable adaptation of declining neighborhoods, (ii) a reduction in automobile use (emission of gas, fuel consumption, and traffic congestion), (iii) the formation of compact districts, and (iv) the enhancement of pedestrian satisfaction and standards of urban living [25,26,27].

Globally, cities like Stockholm, Singapore, and Tokyo showcase the successful implementation of TOD strategies, where the introduction of rail systems has positively influenced standards of urban living. Such cities are referred to in the literature as adaptive cities, which have “created a compact, mixed-use, walking-friendly built form that has enabled high-quality, high-capacity public transit services to thrive” [28]. In the city-state of Singapore, for instance, a national Constellation Plan is guiding its urban development through implementing a sustainable transit system. According to Cervero, this plan consists of “constellation of satellite ‘planets’, or new towns, that orbit the central core, interspersed by protective greenbelts and interlaced by high-capacity, high performance rail transit” [9]. Light rail transit (LRT) systems were recently developed as part of the Constellation Plan, with secondary transport facilities such as bus and park and ride (P&R) networks.

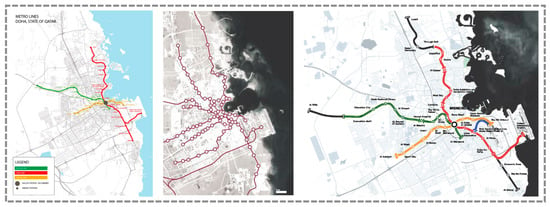

In the case of Qatar, the Qatar Railways Company—Qatar Rail—initiated the construction of the Doha Metro project in 2013, consisting of four lines. The Red line connects the coastal regions in the north of Qatar to the south of the country; the Green line connects Education City to Doha’s cultural core, the Golden line consists of a network of historical districts running east to west, and the future phase of the Blue line is an internal lane within the city of Doha (Figure 1). The Red, Green, and Golden lines depart from the central interchange station in Msherieb Downtown Doha within the city’s most vibrant cultural core, adjacent to Souq Waqif and the Corniche waterfront.

Figure 1.

Maps of the Doha Metro network (source: Qatar Rail 2011).

The success of the metro system as an alternative to vehicular options in Qatar depends on its design, integration, connection, accessibility, and demand by local residents, which recall the key criteria of TOD (the Ds). In this research paper, we argue for the importance of linking Qatar public transportation systems to urban growth patterns through TOD. Specifically, in the sensitive case of the Souq Waqif, TOD can effectively respond to the (i) sustainable adaptation of the neighborhood, (ii) a reduction of automobile use, (iii) the formation of a compact district, (iv) the enhancement of pedestrian satisfaction and standards of urban living, and (v) the preservation and consolidation of the cultural heritage of the site.

2.2. Qatar: (Why Is a TOD Needed in Qatar? How Can We Distinguish a Qatari TOD?) Urban Growth and Cultural Heritage

In this section of the literature review, we attempt to answer the following questions: (i) why is a transit-oriented development needed in Qatar? The answer to this question is linked to urban growth and the rapidity of development, which both require an alternative planning option. The second question is (ii) how can we distinguish a Qatari TOD? In other words, how can we ensure that a TOD in Qatar would reflect its socio-cultural context and respond to its cultural heritage?

2.2.1. Urban Growth

Qatar’s substantial urban settlements were first recorded and documented in the early 1800s–1900s. Prior to the discovery of oil and hydrocarbons, vernacular mud settlements were scattered on the coastline of Qatar as fishing, trading, and pearling villages along with a few pastoral villages in the hinterland. The national population was less than 30,000, and Doha, the capital of Qatar, had a population of 12,000 inhabitants [29]. In the 1950s, the country began a rapid urban revolution caused by the influx of the petrodollar, which was accelerated by the increase in oil revenue after 1971. By 2016, the sprawling city of metropolitan Doha consisted of 1.4 million inhabitants [30].

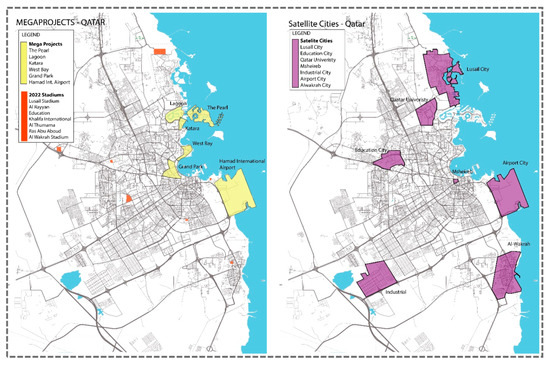

Presently, since 90% of Qatar’s population resides in Doha, the country has taken significant steps towards constructing urban infrastructure and expanding its metropolitan urbanized area [31,32]. Urban megaprojects and large-scale neighborhood developments, such as Education City, Katara Cultural Village, Msheireb Downtown Doha, and Lusail City, as well as the satellite cities and the 2022 World Cup stadiums (Figure 2), are entirely reshaping the urban fringe and fabric of Doha [33,34,35].

Figure 2.

The main megaprojects, satellite cities, and World Cup 2022 stadiums are shown on the map of Qatar. The megaprojects are concentrated along the coastline. The satellite cities are also constructed on a large scale and have reshaped the urban fabric of Qatar (source: the authors based on {Qatar Ministry of Municipality and Environment, MME [36]).

The instant urban growth in Qatar, accompanied by an absent national planning framework, has produced detrimental impacts, such as urban sprawl, traffic congestion, land value increase, affordable housing shortages, and localized negative environmental effects [37]. Therefore, to confront these issues in alignment with an adequate “sustainable urbanism/growth” vision, the Government of Qatar has adopted a national policy called the Qatar National Vision 2030 (QNV-2030) for leading and managing future sustainable development. QNV-2030 is rooted on four pillars: human, social, environmental, and economic development. The human development strategy focuses on citizens’ basic needs, such as healthcare and education. Social development, on the other hand, oversees the establishment of cohesiveness within the entire society. The Ministry of Municipality and Environment (MME) oversees the environment development strategy, and four ministries in cooperation with the Qatar Central Bank have prepared strategies related to economic development. The Qatar National Development Framework (QNDF-2032) stems from QNV-2030 and cumulatively tackles the urban challenges of Qatari cities and urban centers [38,39].

To enhance the standards of urban living, QNDF-2032 foresees the large-scale development of transportation infrastructure in the country, including new road networks and public transit systems, as well as a program of urban regeneration that includes the development of transit villages [40,41,42,43]. Furthermore, QNDF-2032 seeks to achieve sustainable urban development with a balance between modernization, urban growth, and the preservation of heritage culture and identity.

One of the main purposes of QNDF-2032 is to diversify and implement proper urban mobility by enhancing the urban fabric of nodes and centers along the connections and infrastructure networks of the area [44]. To achieve this goal, Qatar launched the construction of the Doha Metro in 2013. This metro began operation in 2019, three years before the 2022 FIFA World Cup event. The Doha Metro project is one of the main contributors to QNV-2030 in resolving (i) the rising demand of the growing population and (ii) the need to enhance urban mobility and reduce overdependence on private vehicles [3,45].

2.2.2. Cultural Heritage

To fit the anticipated TOD planning and design schemes into the socio-cultural context of Qatar, the vision for sustainable urban development raises concerns and challenges related to cultural heritage as an “expression of the ways of living developed by a community and passed on from generation to generation” [46]. Much of the global debate on cultural heritage is concerned with the conservation and sustainable management of heritage sites, where world-class organizations and NGOs play an advocacy role in the process [47,48]. While planning for the sustainable adaptation of communities, planners should also consider contextual issues, challenges, and opportunities, including climatic factors and socio-economic and socio-cultural values. The improvement of public infrastructure, services, and utilities is a principal strategy that requires innovative solutions to maintain the historical–heritage value of historical sites while modernizing the urban fabric, which has been deteriorating. Moreover, transportation policies must be rethought since most cultural heritage sites follow indigenous and spontaneous planning schemes detached from modern transportation systems [49,50,51]. Thus, it is important to integrate the principles of sustainable urbanism, where reliance on eco-mobility, public transportation, and transit systems is key to ensuring sustainable accessibility within conservative heritage districts.

Projecting the broad concept of cultural heritage onto the Middle East region, including Qatar, has triggered an intense debate on the vital cultural assets of Arab heritage, as well as the rapidly evolving socio-economic dynamics of the region [3,32,52]. Therefore, the preservation of cultural heritage extends beyond physical features to include the socio-cultural characteristics of Arab society that are still practiced daily.

One of the most effective principles for the conservation of cultural heritage at an urban scale is the involvement of active governance, which ensures that global policies are effectively translated into locally intensive practices supported by a strong legislative body. In this regard, the QNDF-2032 targets the challenge of the decline in the Qatari identity, sense of belonging, and cultural heritage due to globalization, rapid urbanization, and speculation. According to QNDF-2032:

“Throughout Qatar a more sensitive understanding of the built environment and cultural heritage is required. In the QNDF, emphasis is placed on quantitative and qualitative improvements in the design and provision of parks, gardens, walkways and open spaces. The use of best practice principles in new energy efficient building design whilst conserving the nation’s historic and cultural assets is also promoted”.[39]

The discussion of historic heritage preservation in relation to TOD planning sheds light on the challenges of regeneration and preservation. Hence, the planning scheme for the urban regeneration of the Souq Waqif historic heritage site must focus on fostering the relationship between spatial forms and culture as a way of life, while permitting the development of a place-sensitive TOD characterized by adaptability to site-specific requirements. Site-specific requirements of the Souq Waqif TOD include the following: (i) Souq Waqif has a perceived location, identified geographically with reference to Doha’s shoreline and centralized in the heart of the city. (ii) It is located within a culturally vibrant site due to its commercial activity, thus maintaining its basic essence as a marketplace of Doha. (iii) It is accessible and spatially integrated within the city’s fabric, although it lacks pedestrian connectivity, which could be resolved by a well-planned TOD. (iv) Souq Waqif’s historic evolution and urban character relate to its localization and revitalization in recent decades. (v) It is also a valuable cultural heritage site in the regional context due to its historical roots in Islamic architecture. Recently, (vi) this site has become an attractive destination for tourists, a center and a national landmark to locals, and a leisure spot for the whole city. Incorporating such site-specific criteria into the planning scheme of the Souq Waqif TOD is essential to reflect its socio-cultural context and respond to its cultural heritage.

3. The Research Design

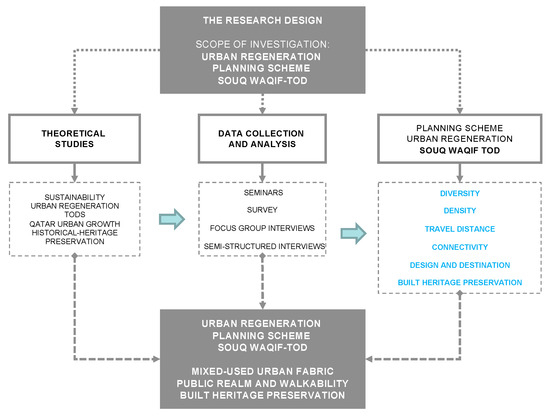

The objectives of this study are (i) to assess the sustainable adaptive transformative potential of the Souq Waqif transit village as a historical–heritage urban node and (ii) to provide applicable solutions to contribute to the urban quality of life of the district. In addition, this study intends (iii) to propose contextualized adapted urban development as a future model for enhancing the long-term health and sustainability of the settlement. We structured our research into three stages, as outlined below.

3.1. Literature Review

The literature review explores the disciplinary context of TOD and related topics to understand the issues, challenges, and opportunities related to the sensitive sustainable adaptation of transit villages in a historical–heritage context [53]. It also provides a brief review of urban growth and development in Qatar as the targeted context of research to assess the potential need for a TOD planning scheme.

3.2. Data Collection and Site Analysis (Graph Theory)

Urbanism and urban design are interdisciplinary fields and thus require an interdisciplinary approach in planning and design through the active involvement of end users/city dwellers, stakeholders, and practitioners. The selected case study was initially explored through a collection of oral and visual data [54,55].

We collected oral data by attending seminars, talks, and unstructured interviews with architects and engineers of various governmental bodies and authorities working in the urban planning sector (e.g., the Ministry of Municipality and Environment (MME)). Amongst the most useful sources were the series of seminars delivered by Mr. Mohammed Ali Abdulla, the designer of the Souq Waqif project, as well as the series of seminars conducted for Souq Waqif’s nomination for the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Such events provide first-hand detailed information on the issues, challenges, and opportunities related to the sensitive sustainable–adaptive planning scheme for the Souq Waqif transit village.

The primary references include visual documentation, historical/cartographic maps, architectural drawings, and photographs of the Souq Waqif area. Secondary references were obtained through a survey distributed in September 2019 to 80 professionals from various governmental agencies, such as the Ministry of Municipality and Environment (MME), Qatar Rail (QR), Qatar Museums Authority (QMA), and Ashghal Public Works Authority. Six categories revealed from the review of theoretical studies were indicated to be the most appropriate for assessing the performance of the selected TOD.

Subsequently, between December 2019 and February 2020, focus group interviews were arranged with 40 participants from the selected governmental agencies. Participants were required to complete an anonymous questionnaire via email to highlight the relative importance of each aspect of success for the selected TOD (as per the pre-identified categories). In addition, 40 end users/citizens/respondents residing in the area were interviewed (semi-structured interviews) and asked to discuss and rate the selected indices and whether further relevant indicators must be listed in the questionnaire.

In addition, inductive and deductive methods—gained through participatory observations, direct site observations, field studies, and on-site analysis—were utilized for the collection of visual data (cartographic maps, aerial views, and photographs). Namely, site analysis based on graph theory provides a method of assessing the transformative potential of the Souq Waqif TOD and identifying the gaps to be addressed in developing a sustainable and adaptive planning scheme for the site [53,56].

3.3. The Urban Regeneration Planning Scheme for the Souq Waqif

Research by design is a commonly applied methodology in urbanism and architecture through two steps: (i) territorial analysis of the investigated area and (ii) the generation of a vision as a way to produce concrete ideas of the investigated area’s metamorphosis through specific design tools. Particular emphasis is given to the interplay between territorial analysis (network analysis based on graph theory) and design exploration (the planning scheme). The resulting planning scheme summarizes the framework that enhances the dependency between mapping and design. As a result, the proposed sustainable–adaptive planning scheme is based on addressing and filling the gaps highlighted through the territorially analyzed design tools of the investigation (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The research design (source: the authors).

4. The Case Study Settings: The Souq Waqif Historical–Heritage Site of Doha

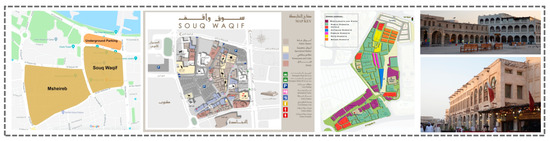

The Souq Waqif (or the local market) is located in the district of Msheireb, near the Museum of Islamic Art and the Corniche waterfront. This site, comprising an area of 164,000 square meters, is one of the top tourist destinations within Doha and displays Qatari-built heritage culture [21] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Map and views of the Souq Waqif in Doha (source: the authors).

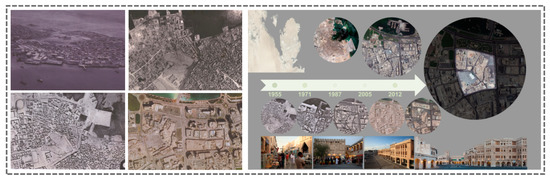

The Souq Waqif, founded a century ago to facilitate the trade of primarily livestock goods, was a labyrinthine market near the city’s waterfront. This part of the city was originally on the shoreline of the Arabian Gulf until developers began turning the water’s edge into more land (Figure 5). Souq Waqif (which means “standing market” in Arabic) is a reference harking back to its beginnings as a gathering place around the riverbed Wadi Msheireb [42,57,58].

Figure 5.

Evolution maps from Ministry of Municipality and Environment (MME) (years: 1947–1952–1955–2005): location and historical profile of Souq Waqif (source: the authors’ graphical regeneration).

Over the three decades preceding the early 2000s, the market was abandoned as malls and other shopping options were developed in Doha. In 2006, the Souq Waqif was subjected to both restoration and reconstruction to preserve its architectural and historical identity [59,60]. Due to the national commercial, touristic, and cultural heritage significance of the site, the metro station located within Doha’s cultural core, bordering the Souq Waqif area, is expected to be one of the busiest nodes with the highest ridership of the entire metro network [61]. Therefore, in this context, it is argued that a contextualized TOD is a key model for the sustainable adaptation of the Souq Waqif transit village, and as such a TOD would revive the spirit and life of the urban fabric, which, in turn, would affect city dwellers’ standards of urban living and the overall health and sustainability of the community.

4.1. Site Analysis and Findings

The proposed strategy for the urban regeneration of the Souq Waqif TOD is centered on the dependency between (i) mapping (on-site analysis based on graph theory) and (ii) an urban design proposal (i.e., a master plan). Therefore, the proposed framework focuses on addressing the gaps highlighted through the territorial analysis, which assesses the performance of the selected TOD based on the six indicators discussed already: diversity, density, travel distance, connectivity, design and destination, built heritage, and preservation.

4.1.1. Diversity

The Souq Waqif metro station is located within a site consisting of low- and medium-density souqs, commercial offices, residential, religious, hotel and public institutions, bank headquarters, mixed-use developments, and significant heritage projects (e.g., the Msheireb project). The metro station, located nearby Doha’s iconic crescent Corniche, connects the three main distinctive districts of the city: (1) the modern northern business district of Wet Bay (or the skyline of Doha), which contains several stunning high-rise buildings; (2) Al Bidda Park (currently under re-development), located in the middle of the Corniche; and (3) the southern area, which includes mid- and low-rise developments and is also identified as the historical and cultural site of Doha. Overall, the mixed-use area utilized for residential, cultural, and touristic purposes is characterized by commercial edges surrounding the zones with residential, touristic, open space, and recreational land uses.

As anticipated, the TOD envisions the integration of a mix of land uses, including residential, civic, and commercial uses, as a strategy for providing services to shape a vibrant community. While an open green area located on the northern boundary of the Souq is directly connected to the Souq and its underground parking facility, the land use map suggests a lack of green pocket areas or nodes within the neighborhood. The nodes, as small green spaces or outdoor neighborhood hubs where people and nature meet for recreation, rest, and community events, should be meaningfully and seamlessly connected to one another by green corridors as green linear lanes providing shade and cooling, as well as accommodating safe, comfortable movement through the urban fabric.

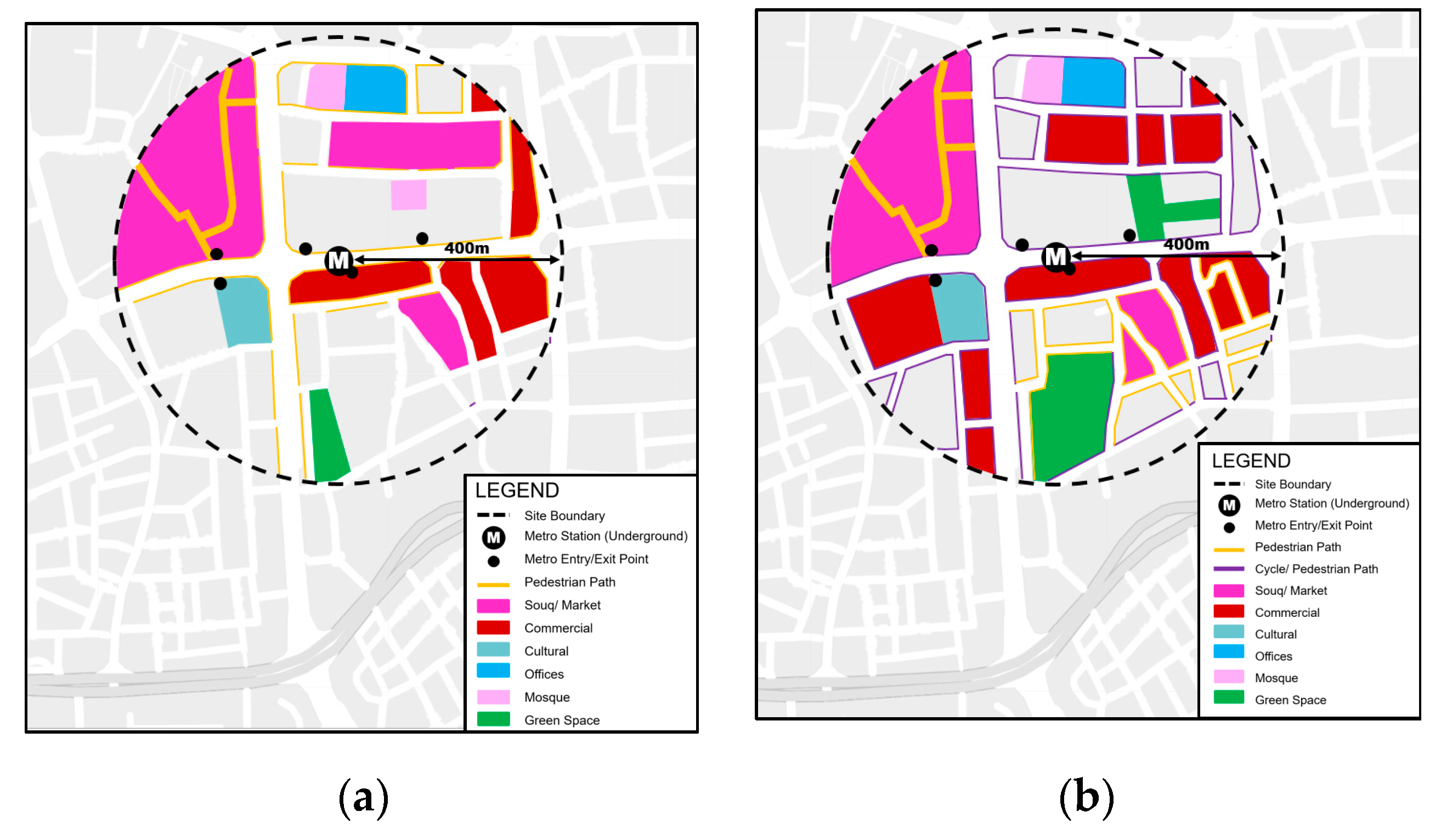

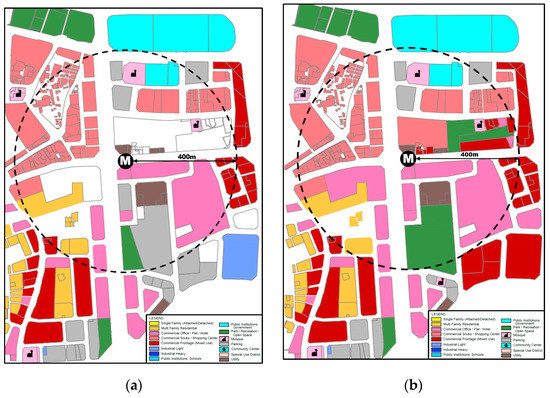

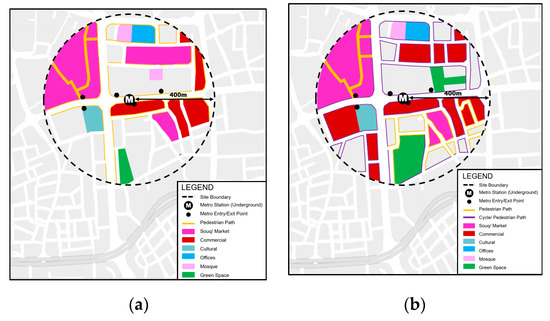

Currently, the site is characterized by a vibrant and active pedestrian environment, efficiently distributed and connected to the new Msheireb project. Moreover, the strategic location between the two metro stations provides the opportunity to concurrently develop and preserve the community’s distinctive urban fabric. Increasing pedestrian accessibility to the surrounding district site would contribute to developing underused areas and enhance livability through the reuse of ineffective buildings (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Land use: (a) existing; (b) proposal (source: the authors).

4.1.2. Density

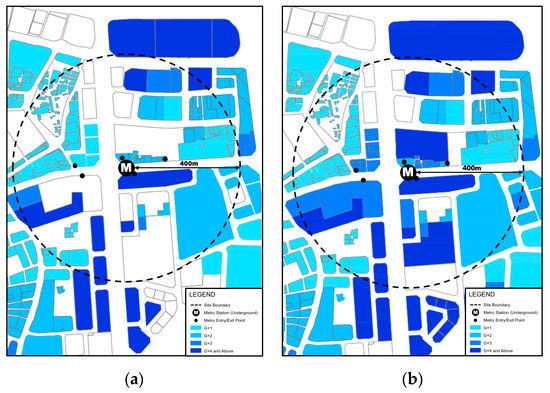

Medium- and low-density levels dominate the area, with 4:1 to 1:1 (vacant) ratios. High-density ratios are found within high-rise buildings on Grand Hamad Avenue, bordering the metro station to the south. As per the 2015 Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics (MDPS) census, this area has a low population concentration compared to the surrounding zones. Additionally, it is relatively high in its establishment distribution, with more than 75% used land.

The proposed planning scheme aims to integrate high-density land such as residential buildings, single-family detached and attached units, and mixed-use commercial units with flats or studios to ensure a constant pedestrian flow to and from the transit access within a comfortable walking distance. This approach would help reduce the current high level of dependency on automobiles (currently the main means of transportation to/from and within the site), which is also supported by the existence of a large new underground parking facility. The new metro station’s presence could reverse this trend through a surrounding built environment supporting high-density development, integrated with a mixed land use that is fully accessible by public systems (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Density: (a) existing; (b) proposal (source: the authors).

4.1.3. Travel Distance

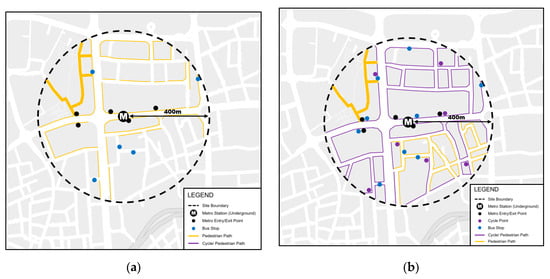

Considering the infill of unused and unbuilt areas, the area should be planned to reduce travel distance, which would encourage the use of the metro station, as well as walking and cycling. Furthermore, distance has critical implications for the viability of multimodal public transport systems. The choice of these different modes of transportation is influenced by various factors, such as land use, cultural, habitual, and practically reasoned components. These factors capture the complexity of transport choices and indicate that accessibility alone is not the determinant for the use of these transit systems. Therefore, interviews with households and city dwellers within and around the site would allow us to better understand how people use walking and cycling as their main transportation modes, where available (Figure 8).

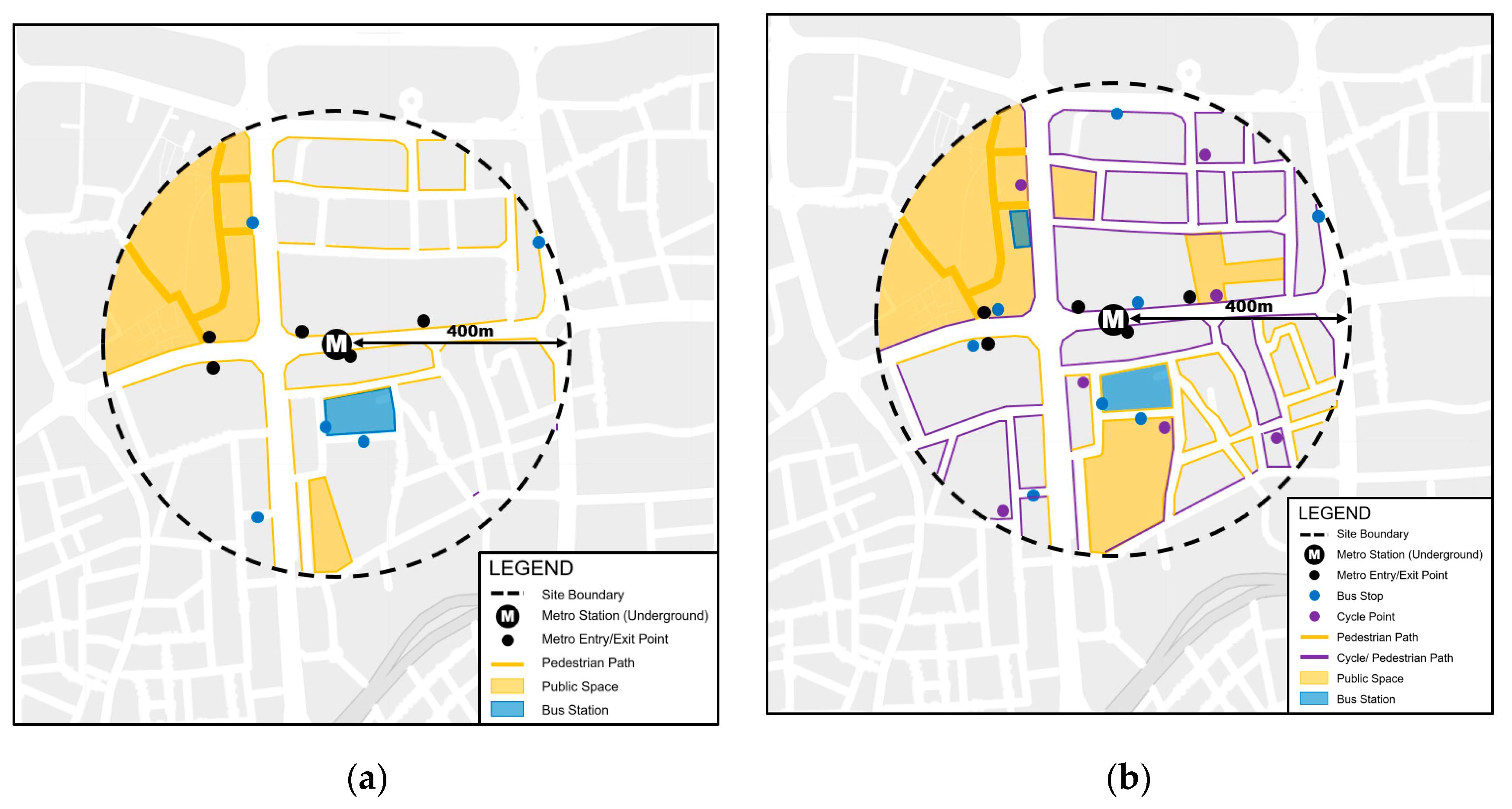

Figure 8.

Travel distance: (a) existing; (b) proposal (source: the authors).

4.1.4. Connectivity: Transport Systems and Public Spaces

Doha is an automobile-dependent city, as most of its urban areas sit within large blocks surrounded by multi-lane highways with grade separations that restrain pedestrian and cycling accessibility. The Souq Waqif neighborhood is surrounded by main streets that are poorly designed for pedestrian use, with large sidewalks dedicated to car parking. Considering these settings, three systems are proposed to enhance connectivity: street networks, reducing the use of automobiles by encouraging walking and cycling, and the integration of multimodal transit systems.

In promoting a less car-dominant lifestyle, the focus is on walkability and cycling. These simple modes of transportation can reduce reliance on private cars for short-distance trips. However, several respondents considered cycling to be an inappropriate approach due to climatic and cultural barriers, arguing that humidity and heat might prevent people from using bicycles as common modes of transportation. In addition, the style of dress for local males and females is considered unsuitable for cycling. The overall conservative culture of Qataris likewise creates a barrier to cycling. Another limitation to cycling is Qatar’s current urban structure, which is based on highway systems. An 800 m trip from Souq Waqif to the neighboring park of Al Bidda takes 15 min by car, with two changes in each direction and requires one to pass through three traffic signals when there is no traffic. However, the same trip can be taken through one line-of-sight pathway using a bicycle in under seven minutes. Therefore, the bicycle infrastructure should be integrated. The climate is restrictive, but cycling remains suitable during the half of the year when Qatar’s weather is pleasant. Appropriate infrastructure, such as special pathways alongside streets or bicycle racks and different amenities should be developed.

Other public transport facilities include bus stations that are accessible within the 400 m radius from the metro station location. However, these bus stops are not accompanied by shaded pedestrian infrastructure. Therefore, pedestrian infrastructure and bicycle lanes should be integrated with existing transit systems, which, in turn, should connect to major metro lines. Intermediate public spaces supporting walkability and climatically adequate (shaded) pedestrian connections, in addition to creating nodes for gathering and mixed-use commercial facilities in between high-rise headquarters, must be planned, as well as pedestrian- and cyclist-friendly networks.

Although the Souq Waqif neighborhood is highly walkable and offers diverse and active movement, the level of the area’s walkability in relation to its edges and surroundings is poor. Most, if not all, the surrounding streets have no decent sidewalks. In this regard, pedestrian connectivity has been provided in three directions: (i) to the north, leading to public governmental agencies and the Corniche; (ii) to the west, through the gold market and Souq Waqif; and (iii) to the south, with access to commercial offices and business centers (in addition to Al Najada Souq and the future developments of its residential quarter). Thus, each direction is treated as an integrated zone with design strategies that align with the destination and user expectation. For instance, (i) the northern zone is expected to include outdoor climatic moderations that capture the sea breeze effectively to improve pedestrian experience and the overall microclimate; (ii) the western zone is an extension of the Souq Waqif, which will offer gradual commercial activities such as open cafes and small culturally themed showrooms, thereby preparing the public for the atmosphere of the Souq Waqif; and (iii) the southern zone includes pedestrian connections that focus on improving accessibility and timesaving approaches to commercial offices and HQs through high-tech pedestrian bridges and skywalks.

There is a need to propose a planning approach for encouraging pedestrian and cyclist connectivity around the metro station. The encouragement of walkability as a healthy pattern of pedestrian mobility within the district and a primary mode of travel should be pursued through the adoption of climatic moderation strategies, which are essential in this context to maintain outdoor thermal comfort due to the overall harsh climatic conditions of the hot–arid Doha. Given the existing orientation of the Souq Waqif TOD, comfortable pedestrian climates could be achieved through the integration of localized land–sea interactions and the cooling effect of prevailing winds, as well as the sea breeze. In addition, considering building heights, in streets and corridors where high- to medium-rise buildings exist, shade and wind flow are supported by the built environment. Mutual shading between towers provides countless possibilities to encourage walkability in well-shaded surroundings, taking advantage of the sea breeze and north winds (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Connectivity: (a) existing; (b) proposal (source: the authors).

4.2. Design and Destination Accessibility

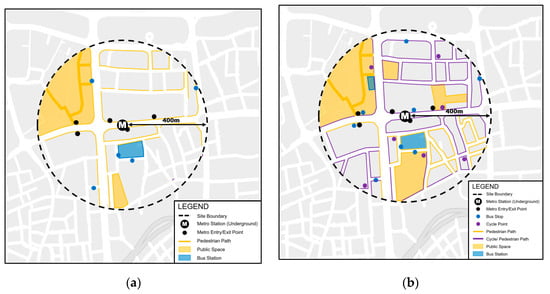

The design aspect relates to an efficient, well-designed built environment. It emphasizes safe and smooth accessibility to transit stations, with the presence of amenities, such as benches, street furniture, trees, and landscaping along the way. This leads to greater mobility by allowing people to move around the city more swiftly and is thus considered an effort for achieving destination accessibility [62]. Many of these amenities are found within the Souq, such as benches, fountains, and street furniture. However, shading elements, signage systems, and free-gathering green spaces are absent.

Moreover, 25% of the Souq area consists of open, empty areas at the edges, with no shelter or use besides their functions as transitional spaces. The Souq also lacks a clear bicycle infrastructure within its boundaries and surroundings. Although connections within the Souq itself have proven efficient, the area lacks easy and safe pedestrian and bicycle connections to its surroundings, as the main priority for transportation remains automobiles.

Therefore, the two main aspects of enhancements needed are street, open space, and station enhancements. While streets could be improved by incorporating efficient signage systems; bicycle lanes; safe, convenient, and comfortable environments for pedestrians and cyclists; curb bump-outs and bright crosswalks; and integrated multimodal connectivity, open spaces and stations could be improved by inserting plazas and open spaces (placemaking to enhance the multimodal circulation network), bike stations, and local art installations and engaging in plaza and open space improvements, thereby providing an improved user experience that is safe, convenient, and comfortable (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Design and destination accessibility: (a) existing; (b) proposal (source: the authors).

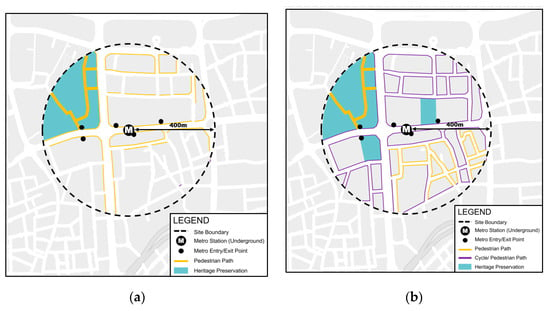

4.3. Built Heritage Preservation

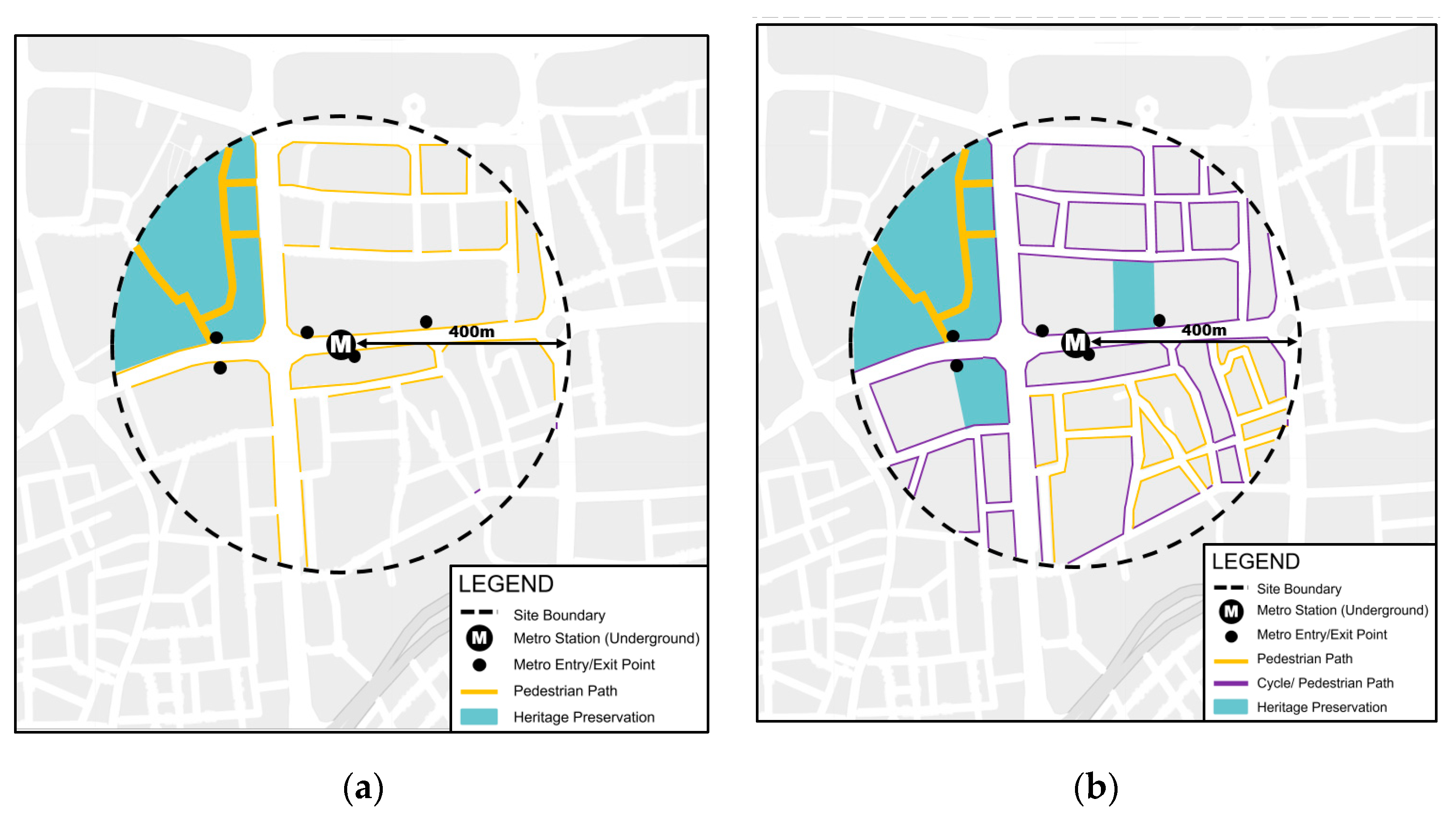

The challenge in the preservation of built heritage extends beyond the physical design of amenities and includes the socio-cultural enhancement of public life in the district [63]. Thus, the sustainable–adaptive planning scheme for the Souq Waqif is strongly related to the approach of anti-global urbanism, which supports the socio-cultural sustainability of the public realm and enriches the cultural heritage of distinctive sites, thereby avoiding the enforcement of imported lifeless architectural forms, embracing the integration of a built form embedding the meaning of a place, and emphasizing tangible and non-tangible sources of identity for individuals and communities.

The Qatari city dwellers’ way of life, along with the area’s richness and cultural meanings, is locally embedded within the urban fabric of the Souq Waqif, even though the site has been revitalized and renewed in its construction and building techniques. Indeed, the principles of the neighborhood are maintained in the Souq Waqif and encompass “the culture, traditions and values of a unified society and through their design express concepts such as extended families, kinship ties, societal activism, local economy, collective identity and a high degree of environmental awareness” [64]. Such principles must be highly integrated as a continuity of style in the sustainable–adaptive planning scheme for the Souq Waqif (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Heritage preservation: (a) existing; (b) proposal (source: the authors).

5. Conclusions

The revenue from oil and gas exports has transformed Doha from a fishing village into a regional economic hub. However, the past decade of rapid economic and urban growth has decreased the standards of urban living. The city has been transformed into a car-dominant, multi-lane superblock environment lacking sustainable modes of transportation, such as walking and cycling. Consequently, under QNV-2030, the State of Qatar launched the construction of Doha Metro along with the urban regeneration of urban villages located around the stations as a comprehensive strategy to pursue sustainable urban growth and urbanism.

This study aimed to explore the impact of the planned metro stations in the Souq Waqif neighborhood as efficient transit-oriented developments (TODs). The Souq lies within approximately 800 m of the station, with clear connections and porosity: Its streets are permeable, walkable, and well connected, with mixed land uses and active ground floors. On the other hand, the Souq’s edges are not well connected to the surroundings and lack pedestrian or cyclist accessibility, as streets are designed to be dominated by automobiles.

As a result, the integration of the recreational spaces of parks, children’s playgrounds, public seating, and plazas, particularly to the west of the Souq, would help enhance the livability of the neighborhood. The close location of the Souq to the Al-Corniche water promenade is also of crucial relevance: the size of the surrounding streets should be decreased to promote the connection of the heritage site with the water promenade and, as a result, to enhance the social, cultural, and architectural sense of the heritage site.

While parts of this paper may appear to be a critique of existing policies or plans or an attempt to provide a set of recommendations to alter and improve these plans, it is important to note that there are currently no on-going policies or plans related to TODs in Qatar, other than the brief conceptual mention of transit-oriented development in QNDF-2032. TOD is a very recent theoretical approach that we aim to promote in Qatar to establish planned schemes for further implementation and adoption by responsible stakeholders. An urban regeneration planning TOD scheme is urgently required in Qatar, specifically for heritage sites, as discussed throughout the paper.

6. Discussion

The assessment of the Souq Waqif neighborhood through the key criteria of TODs allowed us to define recommendations for elements that were found to be missing in the Souq Waqif but could contribute to the main principles of TOD, including pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure, traffic-calming techniques, more public seating, more shading elements, clearer signage, and free green pockets for gatherings. In addition, the findings reveal that the city should consider changing its citizens’ preferences for low-density housing in the districts around Souq Waqif. Enforcing dense neighborhoods with increased residential densities will also aid in decreasing the distance traveled from the metro station to the surroundings. However, enforcing high-density developments among citizens that prefer low-density neighborhoods due to cultural norms challenges the dimension of sustainability; people should be satisfied and feel attached to their living environments. To mitigate such oppositions, experts and politicians should educate the public about TODs through open avenues. To completely understand the opportunities of transparent planning approaches for Qatar’s neighborhoods through TODs, future research should explore the means of engaging the public in urban planning.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed to this research study as follows: Conceptualization, R.F.; methodology, R.F.; software, R.F., A.A.-M.; validation, R.F., A.A.-M.; formal analysis, R.F., A.A.-M.; investigation, R.F., A.A.-M.; resources, R.F., A.A.-M.; data curation, R.F., A.A.-M.; writing—original draft R.F.; preparation; R.F., A.A.-M.; writing—review and editing, R.F., A.A.-M.; visualization, A.A.-M., R.F., supervision, R.F.; project administration, R.F., A.A.-M.; funding acquisition, R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research study was developed under two grant schemes awarded by Qatar University (Grant ID: QUCG-CENG-1920-4) (Grant ID: QUST-2-CENG-2020-14). English editing, proofreading and Open access (OA) publication fees of this paper were supported by Qatar University (Grant ID: QUCG-CENG-1920-4) (Grant ID: QUST-2-CENG-2020-14).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Qatar University for creating an environment that encourages academic research and unlocks the creative potential of budding researchers and for funding for the open access (OA) publication of this article. Also, the authors would like to acknowledge the support of Eng. Labeeb Ali for assisting Raffaello Furlan in the preparation of the visual material. This paper was subject to a Double-Blind Peer Review process. Once accepted for publication, the journal ‘Sustainability’ offered the authors the choice to publish this article on open access (OA), fully supported by the Qatar University. Finally, the authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments, which contributed to an improvement of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Bank Open Data: Qatar. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 25 August 2020).

- Furlan, R.; ElGahani, H. Post 2022 FIFA World Cup in the State Qatar: Urban Regeneration Strategies for Doha. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2018, 11, 355–370. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, R.; Petruccioli, A.; Major, M.; Zaina, S.; Saeed, M.; Saleh, D. The Urban Regeneration of West-Bay, Business District of Doha (State of Qatar): A Transit Oriented Development Enhancing Livability. J. Urban Manag. 2018, 8, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, R.D.; Ferbrache, F. Transit-Oriented Development and Sustainable Cities. Economics, Communities and Methods; Knowles, R.D., Ferbrache, F., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, P. Cities and Design; Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, P.; Skyes, H.; Granger, R. Urban Regeneration; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, M. Sustainability Principles and Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bay, J.H.P.; Lehmann, S. Growing Compact-Urban Form, Density and Sustainability; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cervero, R. Public Transport and Sustainable Urbanism: Global Lessons. In Transit Oriented Development: Making it Happen; Renne, J.L., Curtis, C., Bertolini, L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 23–35. ISBN 9780754673156. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, C.; Renne, J.L.; Bertolini, L. Transit Oriented Development: Making it Happen; Ashgate Publishing Company MPG Books Ltd.: Bodmin, Cornwall, UK, 2009; ISBN 9780754673156. [Google Scholar]

- Renne, J.L. Measuring the success of transit oriented development. In Transit Oriented Development: Making it Happen; Curtis, C., Renne, J., Bertolini, L., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Bodmin, Cornwall, UK, 2009; pp. 241–255. ISBN 9780754673156. [Google Scholar]

- Al Saeed, M. Transit-oriented development in West Bay, Business District of Doha, State of Qatar. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 9, 394–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D. The Age of Sustainable Development; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Calthorpe, P. Urbanism in the Age of Climate Change; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J.; Svarre, B. How to Study Public Life; Island Press: Washigton, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ogra, A.; Ndebele, R. The Role of 6Ds: Density, Diversity, Design, Destination, Distance, and Demand Management in Transit Oriented Development (TOD). In Proceedings of the NICHE-2014 Neo-International Conference on Habitable Environments, Jalandhar, India, 31 October–2 November 2014; pp. 539–546. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzeo, L.; James, N.; Young, G.; Farrell, B. Sustainable Places: Delivering Adaptive Communities. In Building Sustaianble Citities of the Future; Bishop, J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 163–193. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, L. La Cultura delle Citta; Edizioni di Comunita: Milano, Italy, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, R.; AL-Harami, A. Qatar National Museum-Transit Oriented Development: The Masterplan for the Urban Regeneration of a ‘Green TOD’. J. Urban Manag. 2020, 9, 115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Linchuan, Y. Evaluating the urban land use plan with transit accessibility. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 45, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, R.; Petruccioli, A.; Jamaleddin, M. The authenticity of place-making: Space and character of the regenerated historic district in Msheireb, Downtown Doha (State of Qatar). Archnet IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2019, 13, 151–168. [Google Scholar]

- AL-Mohannadi, A.; Furlan, R. Socio-cultural patterns embedded into the built form of Qatari houses: Regenerating architectural identity in Qatar. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2019, 12, 336–358. [Google Scholar]

- Ehsani, M.; Wang, F.-Y.; Brosch, G.L. Transportation Technologies for Sustainability; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Plattus, A.J.; Shibley, R.G. Time-Saver Standards for Urban Design; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. The Mutual Interaction of People and their Built Environment; Aldine Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira, F.L. Green Wedge Urbanism-History, Theory and Contemporary Practice; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zaina, S.; Zaina, S.; Furlan, R. Urban Planning in Qatar: Strategies and Vision for the Development of Transit Villages in Doha. Aust. Plan. 2016, 53, 286–301. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, H.; Cervero, R.; Iuchi, K. Transforming Cities with Transit. Transit and Land-Use Integration for Sustainable Urban Development; The World Bank: Washigton, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Adham, K. Rediscovering the Island: Doha’s Urbanity from Pearls to Spectacle. In The Evolving Arab City: Tradition, Moderniy and Urban Development; Elsheshtawy, Y., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Remali, A.M.; Salama, A.M.; Wiedmann, F.; Ibrahim, H.G. A chronological exploration of the evolution of housing typologies in Gulf cities. City, Territ. Archit. 2016, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Asiri, A. Sustainable Urbanism: Adaptive Re-Uses For Social-Cultural Sustainability in Doha. Master’s Thesis, Hamad Bin Khalifa University in Doha, Doha, Qatar, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, R.; Sipe, N. Light Rail Transit (LRT) and Transit Villages in Qatar: A Planning-Strategy to Revitalize the Built Environment of Doha. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2017, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, A. Rapid urban development and national master planning in Arab Gulf countries. Qatar as a case study. Cities 2014, 39, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Mohannadi, A.S.; Furlan, R. The Practice of City Planning and Design in the Gulf Region: The Case of Abu Dhabi, Doha and Manama. Archnet IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2018, 12, 126–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, R.; Petruccioli, A. Affordable Housing for Middle Income Expats in Qatar: Strategies for Implementing Livability and Built Form. Archnet IJAR, Internatinal J. Archit. Res. 2016, 10, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MME Ministry of Municipality and Environment. Available online: http://www.mme.gov.qa (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- Rizzo, A. Metro Doha. Cities 2013, 31, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Mohannadi, A.; Furlan, R.; Major, M. Socio-Cultural Factors Shaping the Spatial Form of Traditional and Contemporary Housing in Qatar: A Comparative Analysis Based on Space Syntax. In Proceedings of the 12th International Space Syntax Symposium Proceedings, Beijing, China, 8–13 July 2019; Beijing Jiao Tong University: Beijing, China, 2019; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- QNDF. Qatar National Development Framework 2032; Ministry of Municiplity and the Environment: 2014. Available online: http://www.bluepenjournals.org/ijres/pdf/2019/October/Al-Thani.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- Jodidio, P.; Halbe, R. The New Architecture of Qatar; Skira Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, K. The Qatar National Master Plan. In Sustainable Development: An Appraisal from the Gulf Region; Sillitoe, P., Ed.; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fromherz, A. Qatar: A Modern History; I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd.: Washigton, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jaidah, I.M.; Bourennane, M. The History of Qatari Architecture from 1800 to 1950, 1st ed.; Skira Editore: Milano, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, R. Light Rail Transit and Land Use in Qatar: An Integrated Planning Strategy for Al-Qassar’s TOD. Archnet IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2016, 10, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, R.; Alattar, D. Urban Regeneration in Qatar: A Comprehensive Planning Strategy for the Transport Oriented Development (TOD) of Al-Waab. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2017, 11, 168–193. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. International Cultural Tourism Charter: Principles and Guidelines for Managing Tourism at Places of Cultural and Heritage Significance (Report); Burwood, VIC, Australia, 2002; Available online: http://openarchive.icomos.org/607/1/308.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- Jokilehto, J. A History of Architectural Conservation; Oddy, A., Linstrum, D., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Culture: Urban Future. Global Report on Culture for Sustainable Urban Development; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Siravo, F. Planning and Managing Historic Urban Landscapes. In Reconnecting the City. The Historic Urban Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage; Bandarin, F., van Oers, R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, R.; Petruccioli, A. Doha come citta’ multietnica: Pianificazione urbana e nuovi spazi insediativi delle communita’ migranti. Urbanistica 2020. Accepted for Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, R. Modern and Vernacular Settlements in Doha: An Urban Planning Strategy to Pursue Modernity and Consolidate Cultural Identity. Arts Soc. Sci. J. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, E.; Kourtit, K.; Nijkamp, P.; Painho, M. Spatial analysis of sustainability of urban habitats, introduction. Habitat Int. 2015, 45, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.; Rossman, G. Designing Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Thousand Oaks: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsson, R. Case Study Methodology. In Proceedings of the International Conference Methodologies in Housing Research, Stockholm, Sweden, 22–24 September 2003; Available online: www.psyking.net/HTMLobj-3839/Case_Study_Methodology-_Rolf_Johansson_ver_2.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- Ragin, C. Constructing Social Research; Pine Forge Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fromherz, A.J. Qatar-Rise to Power and Influence; I.B Tauris & Co. Ltd.: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Salama, A.M.; Wiedmann, F. Demystifying Doha. On Architecture and Urbanism in an Emerging City; Ashgate Publishing Ltd.: Surrey, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, R.; Tannous, H. Livability and Urban Quality of the Souq Waqif in Doha (State of Qatar). Saudi J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 3, 368–387. [Google Scholar]

- Nafi, S.I.; Alattar, D.A.; Furlan, R. Built Form of the Souq Waqif in Doha and User’s Social Engagement. Am. J. Sociol. Res. 2015, 5, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, R. Urban Design in the Arab World: Reconceptualizing Boundaries; Ashgate Publishing: Burlington, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tannous, H. Traditional Marketplaces in Context: A Comparative Study of Souq Waqif in Doha, Qatar and Souq Mutrah in Muscat, Oman. Master’s Thesis, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Molotch, H.; Ponzini, D. The New Arab Urban. Guld Cities of Wealth, Ambition, and Distress; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bullivant, L. Masterplanning Futures; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).