Abstract

There is a need to monitor the growing prevalence of childhood weight issues and obesity worldwide. Parents can establish a set of family rules regarding child behaviors, but parents’ favorable attitudes toward healthy nutrition are also necessary. Despite the importance of this issue, there has been very little research on the most efficient means of communication to improve parental intentions to give fruits and vegetables to their children. Social marketing plays a key role in formulating effective communication campaigns targeting parents. We focus on two elements of the communication process, the message endorser and the message framing, and run an experiment with a sample of parents. Results demonstrate that parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables to children will be higher when the related message is backed by an expert endorser (vs. a celebrity endorser), the message is positively framed (vs. negatively framed) and when the message is emotionally framed (vs. rationally framed). Moreover, there is an interaction effect between the influence of the expertise/celebrity characteristic of the endorser and the message framing on parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables, and the effect is higher when the rational message framing is endorsed by an expert.

1. Introduction

Adult and childhood obesity has become pandemic in recent decades in Western countries [1]. Prevention of childhood obesity is now an urgent issue for public health, particularly in many industrialized countries. As family is the first, and one of the most important, socialization agents, with parents being responsible for buying food, cooking, and, in general, governing eating habits at home, the behavioral eating norms prevailing at home do play an essential role in childhood obesity. Family rules regarding food and children may favor behaviors such as fussy eating and consumption of junk or fast food, which clearly influence children’s weight [2].

One approach by which to tackle childhood obesity through healthy eating is to increase the share of low-density foods in children’s diets—namely fruit and vegetables. Literature has shown that behavior-based interventions contribute to children’s behavior changes [3,4] and, at a low rate, to fruits and vegetable intake [5]. However, despite the relevance of the childhood obesity problem, literature has not considered how communication activities with strong foundations on consumer behavior can contribute to changes toward healthier behaviors that can reduce childhood obesity. Parents have a significant influence on their children’s diet [6], and a simple and cost-effective social marketing intervention (postcard administered to families with children aged 5 to 12 years) may favorably influence parents’ practices with regard to feeding [7]. Communication activities via social marketing can lead to changes in parents’ attitudes, intentions, and behaviors that may serve to change children’s habits related to fruit and vegetable consumption at home. In this respect, as children are a focal concern for their parents, the message content is a key element in communication effectiveness [8].

Communication activities, such as advertising (e.g., tv commercials) and promotions (e.g., product gifts), are highly persuasive and commonly used to encourage children to consume products, offering them positive emotions and experiences as purchase benefits [8,9]. The efficacy of these communication activities implemented by many companies works against public strategies for the prevention of childhood obesity. This idea extols the relevance of public advertising campaigns to sending effective messages, not only to children but also to parents. However, the message content, in addition to the increasingly competitive media environment, may lead social advertising campaigns to fall short, or even backfire.

While previous studies have shown that communication campaigns addressed to parents increase awareness and beliefs [10], and even children’s intake of fruits and vegetables [11], more studies are needed concerning the message of these communication activities. Many communication interventions have focused on positive messages focusing on food healthiness, but they have proven to be not enough to significantly influence families [12]. More studies on message characteristics are, therefore, needed to look for more effective ways to favor healthier behaviors for children. Moreover, when parents make food decisions for the family, they take into account criteria that are different to those used for their own food decisions [13].

The goal of this research is to find efficient patterns of advertising messages in order to increase parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables to children. To achieve this goal, we run an experimental study that assesses which types of endorsers and message framing are most efficient to increase parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables to children. We want to determine how to design the most effective message for communication campaigns to change parental intentions to provide fruits and vegetables to children. To this end, we propose a framework regarding endorsement and message framing. The results can be used by public administrations and private organizations to implement effective childhood obesity prevention and communication policies specifically in the domain of fruit and vegetable consumption.

2. Literature Background and Hypotheses

Previous research has found evidence of a positive relationship between children’s fruit and vegetable intake and parental feeding style [14], home availability/accessibility [15], and parental eating behavior [16]. Parents can influence their children’s diet in many ways, such as through food provision, child-feeding behaviors/strategies, role modeling, or social eating environment [6], or even through feeding strategies such as rules, table food management, and verbal instructions [14]. Parental modeling and parental intake are positively associated with children’s fruit and vegetable consumption [17]. As shown by Kristjansdottir et al. [18], the strongest determinants of fruit and vegetable intake are availability at home, modeling, demanding family rules, and knowledge of recommendations.

In response to the increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity, public health efforts to curb these conditions have been delivered in abundance. However, there is concern that the messages used to target these conditions may be increasing risk factors for disordered eating; for example, Bristow et al. [19] research provided both quantitative and qualitative insights into how public communication messages may have adverse effects on eating behaviors. High vegetable consumption during childhood is important for children’s optimal health and development, and the prevention of obesity and associated chronic diseases later in life [15].

Public health communication strategies aimed at parents may certainly benefit from knowledge of the determinants of message effectiveness when promoting healthy child feeding behaviors [20]. One way to raise awareness among parents and change their behavior and attitudes is to use communication, which in this area of health can be classified as social marketing [4]. Indeed, parents’ exposure to energy-dense food advertising has been found to be associated with more positive attitudes toward feeding fruits and vegetables [21].

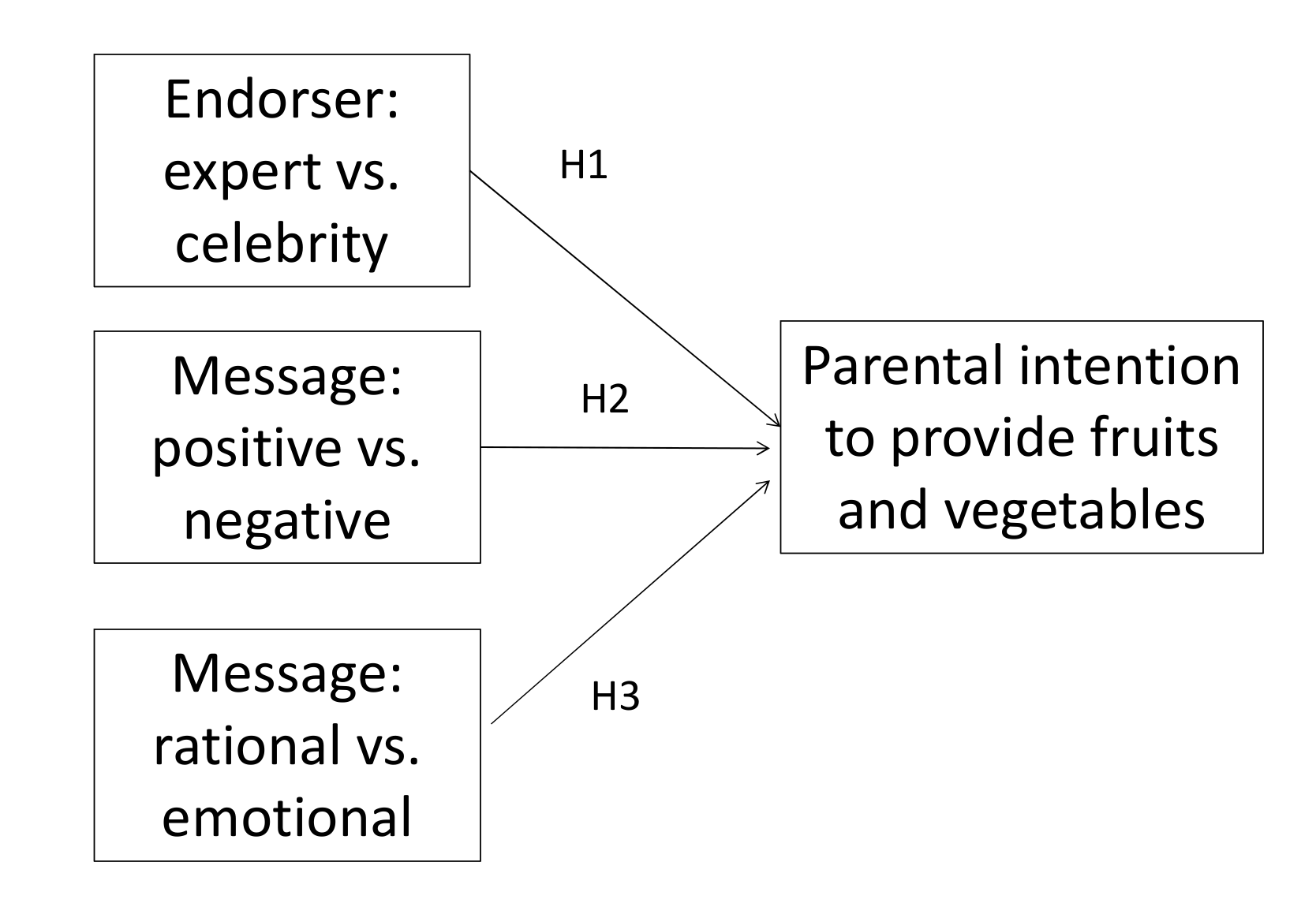

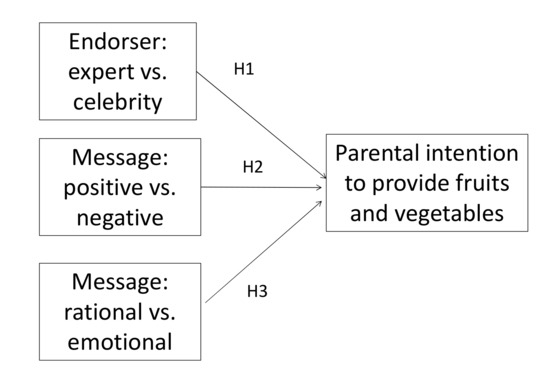

Communication campaigns comprise an organized activity directed at a particular population for a particular period in order to achieve a specific goal [13,22]. Communication planners often establish a theoretical model of how changes in behavior might take place, and use this to guide their goal setting and message design [23]. One of the main communication functions is changing attitudes, intentions, and behavior [24]. Mass media campaigns can produce positive changes in health-related behaviors across large populations. In order to conduct a persuasive communication campaign, however, all elements must be utilized effectively so that the desired goals can be attained. Sources and their credibility are a key aspect of persuasive message presentation [25]. To increase the acceptance of a message, the campaign must thus select credible spokespeople and organizations that balance the two dimensions of credibility: trustworthiness and expertise [26,27]. Message is another important element of the communication process. Depending on its configuration, the message will attract the receivers’ attention and be more or less persuasive. Messages need to capture attention and be easily remembered by all members of the target population [28]. This goal can be accomplished by using multiple executions (different versions of the same underlying concept); being creative and novel; refreshing media messages often; representing people who are clearly members of the target population; ensuring messages are of high quality; using explicit, intense, emotional, or entertaining messages; and including logos, slogans, or jingles [29,30]. We propose that the type of endorser (expert vs. celebrity) and the message framing (rational vs. emotional, positive vs. negative) impact parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables to their children (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Impacts on the effectiveness of healthy-eating messages aimed parents.

2.1. Endorser: Expert vs. Celebrity

Recommendations about a healthy diet can be communicated to parents through various sources, such as experts in nutrition. This is similar to the tactics companies employ daily in terms of using message endorsers such as models or product experts. Because acceptance is one of the main goals of such messages, many companies design their communication campaigns to utilize credible spokespeople and organizations that balance trustworthiness and expertise [26]. Sources and their credibility are a key aspect of message persuasion [25].

Source credibility theory explains how perceived credibility of the source influences a communication’s persuasiveness [31,32]. The credibility of any communication, regardless of its format, is heavily influenced by the perceived credibility of the source of that communication [33]. Source credibility can be enriched by the incorporation of source attractiveness [34], and trustworthiness associated with the perceived honesty of a celebrity endorser [35]. Source model theory [25] combines the two traditional facets of the endorser effect—credibility and attractiveness—to explain how trustworthiness and likeability contribute to communication effectiveness.

A celebrity endorser is “any individual who enjoys public recognition and who uses this recognition on behalf of a consumer good by appearing with it in an advertisement” ([36], p. 310). Celebrities also add value to the brand [36] and enhance message persuasion, which, in turn, contributes to advertising effectiveness [37]. However, Callcott and Phillips [38] suggested that celebrity endorsements are more appropriate for low- than for high-involvement products. On the other hand, an expert is a person with some ability to share information with others based on their experience, education, or competence [39]. That ability is essential to ensure the audience develops a set of associations linked to the brand/product, which is one of the main goals of advertising.

According to extant literature, expert endorsements enhance the believability of an advertisement primarily due to the increased source credibility endorsements provide [22]. We argue that parents care about the health of their children, and that this will drive them to pay more attention to, and process more deeply, information received from experts versus celebrities concerning food products for children. In other words, parents will pay greater intention to communications aimed at increasing the amount of fruits and vegetables they feed to their children when these messages come from experts. We therefore propose:

Hypothesis (H1).

Parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables to children will be higher when the related message is backed by an expert endorser than when is backed by a celebrity endorser.

2.2. Message Framing: Negative vs. Positive

Prospect theory [40] proposes that when faced with two choices (one posing little risk and one posing some higher degree of risk), a person’s preference for one option over the other will be influenced by the way the choices are framed. If the choices emphasize potential losses, individuals are often willing to choose the risky option, as they wish to prevent those losses. However, if the choices emphasize potential gains, individuals are generally less willing to choose options that involve risk in order to secure those gains. Rothman and Salovey [41] applied this reasoning to how people might respond to framed health messages. They suggested that gain-framed messages should be more effective than loss-framed messages for promoting health behaviors perceived to be only minimally risky. For health behaviors whose performance is associated with a higher perceived degree of risk, loss-framed messages should be more effective.

The elaboration likelihood model [42] can also be used to explain how people respond to positively- or negatively-framed messages. Health messages can be framed to highlight either the benefits of engaging in a particular behavior (a gain-frame, or positive-frame) or the consequences of failing to engage in a particular behavior (a loss-frame, or negative-frame) [43]. For example, a gain-framed message aimed at increasing parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables to their children might be “Giving fruits and vegetables to your children will improve their health.”

Following Gallagher and Updegraff [43], gain-framed messages are significantly more persuasive than loss-framed messages in promoting actual preventive health behavior (smoking cessation, skin cancer prevention, and physical activity). They found no case in which there was a significant loss-frame advantage within any specific domain of behavior prevention. This conclusion is in line with the idea that, in many circumstances, messages that evoke positive emotions may have a greater impact on the target group compared to those evoking negative emotions, such as fear [44]. In summary, positive messages are more effective when it comes to persuading audiences to perform a behavior. Therefore, we posit the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (H2).

Parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables to children will be higher when the related message is positively framed than when it is negatively framed.

2.3. Message Framing: Emotional vs. Rational

The goal of communication is persuasion [45]. Organizations have a common goal when they create advertisements for magazines, newspapers, television, or radio, which is to persuade consumers to perform a certain behavior. Two common marketing techniques used by organizations to convince consumers to perform a behavior are rational and emotional message framings.

Following Wood [46], when an advertiser uses rational appeal, it is also appealing to the consumer’s logic—to their systematic processing system. On the other hand, by nature, human beings are emotional creatures. Organizations use a variety of techniques to appeal to consumer emotions. Although many advertisements use a combination of both types of appeal (rational and emotional), a distinct difference exists between advertisements that are primarily rational and those that are primarily emotional. The type of organization, the products it sells, and the services it provides all play a role in the type of marketing appeal utilized [47]. For example, nonprofit organizations (NPOs) that seek consumer donations may use more emotional appeals; these may include facts and statistics to show that the cause is real and valid, but the NPO must appeal to human emotion in order to drive a response [48].

The above-described research allows us to conclude that a rational framing can be more efficient for technological and durable goods, in the credence service condition, when the individual has a tendency to engage in systematic processing thinking. On the other hand, the emotional framing can be more persuasive in the experience service condition. The bottom line of the communication is a rational message aimed at transmitting a scientifically proven message—that is, “If you provide fruits and vegetables to your children they will be healthier”—but the relationship between parents and children is more emotional than rational [49]. For most parents, the wellbeing of their children is one of their primary goals. This is an emotional feeling, rather than a rational one. When parents receive an emotional message, their cognitions will be more consistent than when this message is rational, and therefore the persuasion of an emotional message will be higher than that of a rational message. Therefore, we posit the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (H3).

Parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables to children will be higher when the message is emotionally framed than when it is rationally framed.

2.4. Interaction Effects

The theory of cognitive dissonance [50] postulates that messages may be consonant (i.e., consistent), dissonant (inconsistent), or irrelevant to each other. If a cognitive inconsistency of sufficient magnitude is present, then an individual will perceive psychological discomfort, leading to an attempt to restore cognitive balance by reducing or eliminating the inconsistency [51,52]. Credibility has a positive and significant influence on the receiver’s acceptance of the message.

Most people have a stereotypical picture of scientific experts as more rational individuals, and of artists such as actors, painters, and musicians as being more emotional people. We expect that receivers will perceive high fit between an expert and a rational message, and between a celebrity and an emotional message. Thus, a rational message promoted by an expert endorser will be more consistent to the receiver than a rational message presented by a celebrity endorser, and therefore more persuasive. We predict that we will find an interaction effect when the rational-framed message is endorsed by someone who is an expert on the issue. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (H4).

There is an interaction effect between the influence of the expertise/celebrity characteristic of the endorser and the message framing on parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables. The effect will be higher when the rational message framing is endorsed by an expert.

3. Method

The experiment comprised a 2 (endorser: expert vs. celebrity) × 2 (message: emotional vs. rational) × 2 (message: positive vs. negative) between-subjects design. Each of the eight groups of parents was exposed to a different ad combining independent variables: celebrity endorser vs. expert endorser; negative vs. positive framing of the message; and rational vs. emotional framing of the message. We kept a database of parents belonging to 41 schools in a Spanish region. The questionnaire was pretested with a marketing and nutritional expert panel. Before sending the final questionnaire, a trial run was carried out to check that the parents understood everything. In this pretest, we asked the recipients to highlight any questions that were unclear or confusing. We asked the respondent to think about their eldest child in primary school (from grade 1 to 6, aged 6 to 12 years old), and answer the questions after carefully reading the ad presented to them. The self-administered questionnaire was sent to 1463 respondents via email, and 290 parents clicked the link and completed the questionnaire. On the first page, the entire process was explained and consent to participate in the study was obtained.

After reading the landing page, they clicked the “access” button and were then randomly exposed to one of the eight different conditions. Every ad included an image of the official logo of the Spanish Ministry of Health, in order to promote realism. The celebrity endorser that backed half of the ads was the actor George Clooney, while in the other four ads an expert endorser, referred to as a Harvard University professor specializing in pediatrics, Dr. Marshall, was shown. Regardless of which endorser was presented, the message framing (rational: rationally, recent scientific studies have shown…; emotional: emotionally, it is very satisfying to see…; see below) and valence (positive: their chances of having a healthy weight … positive; negative: likelihood of being overweight … negative; see below) of each ad, the message intention, and length was always the same, and covered the importance, in terms of health and mood, of providing fruits and vegetables to children. The full message was as follows:

“(Rationally recent scientific studies have shown/Emotionally, it is very satisfying to see) that the more fruits and vegetables you provide to your children, the greater their (chances of having a healthy weight/likelihood of being overweight). Additionally, a healthy diet improves their health and mood regulation. Providing plenty of fruits and vegetables is (a rational/emotional positive/negative) choice.”

The questionnaire started with instructions to view and carefully read the ad and complete the questionnaire. The dependent variables were then assessed—that is, parental intention to provide fruits to their children and parental intention to provide vegetables to their children. With these two variables we constructed a composite variable named “parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables to their children.”

We used Machleit et al.’s [53] scale to measure behavior and intention to provide fruits, and also to measure intention to provide vegetables, to their children. Afterwards, we included items to check the manipulation of the endorser’s attractiveness through a scale adapted from Feick and Higie [54]. In addition, we checked the manipulation of the message and valence through scales proposed by Maheswaran and Meyers-Levy [55].

In order to account for additional effects on parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables to children (dependent variable, DV), we considered four control variables. According to the theory of planned behavior, attitudes are an antecedent of intention [56]; however, they not only apply to intentions to buy or consume products, but also to intentions to use products. Attitudes towards fruits and vegetables, measured using the Child Feeding Questionnaire [57], are also an antecedent of the DV. Gender of the parent comprised the second control variable, since women show more positive attitudes towards fruits and vegetables [58] and are more likely than men to consume these low-density products [59]. In addition, more-educated parents typically have access to more information and are more aware of the advantages of giving fruits and vegetables to their children. Parental education level has been found to have a positive correlation with children’s daily fruit and vegetable intake [60]. Finally, our fourth control variable was children’s age. As children grow older, they usually tend to consume more fruits and vegetables [61]; therefore, the age of the child was expected to have a reverse effect on the DV.

Sample Description

The sample included 226 mothers (77.9%) and 64 fathers (22.1%), predominantly with a university degree (66.6%). Respondents children comprised 143 girls (49.3%) and 147 boys (50.7%) aged between 6 and 15 years old. Even if mothers/fathers variable was not balanced, there were enough parental observations to consider this variable in the study. Each of the parents was randomly assigned to one of the eight treatments. The sample distribution across the different treatments is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample distribution of treatments.

The minimum number of individuals in one treatment condition was 29 and the maximum was 48. The mean size per cell was 36. The celebrity endorsement scenario had 138 cases, while there were 152 in the expert condition. The negative framing situation comprised 132 respondents, and there were 158 in the positive one. The emotional framing scenario had 151 cases and the rational one had 139. The scales’ reliability was assessed through Cronbach’s alpha. Reliability was found to be high and exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70 for all scales.

4. Results

4.1. Manipulation Check

We used one-way analysis of variance in order to check that all the manipulations and treatments were well understood by the respondents. All manipulations showed significant differences between conditions. When we asked the interviewees if the person in the ad was a celebrity (1: “not celebrity” to 7: “celebrity”), the respondents indicated that George Clooney was more celebrity than Dr. Marshall, as intended (MClooney = 5.50; MDrMarshall = 3.07; F(1289) = 139.11; p < 0). We also asked the respondents if they thought the subject in the ad was a nutritional expert (1: “not an expert” to 7: “very much an expert”). As expected, the respondents found Dr. Marshall to be more of a nutritional expert than George Clooney, and the average difference was statistically different from zero (MClooney = 2.82; MDrMarshal = 5.66; F(1289) = 156.20; p < 0). Parents were asked, using a seven-point semantic differential scale (1: “very negative” to 7: “very positive”), whether the ad message framing was more negative or positive. The subjects found the positive ad to be more positive than the negative one (MNegative = 3.87; MPositive = 5.65; F(1289) = 65.87; p < 0).

Finally, respondents were asked, using a seven-point semantic differential scale (1: “very emotional” to 7: “very rational”) whether the message was more emotional or rational. The results were again significant (MEmotional = 4.12; MRational = 5.26; F(1289) = 29.12; p < 0) and in the expected direction.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

A three-way ANCOVA was used to confirm the hypothesis. Most studies have considered the consumption of both products together—that is, fruits and vegetables as a single product [14]. We measured these separately, but built a composite variable to join them into a variable “parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables to their children”. In order to be consistent with the literature, control variables were included as covariates: (1) parents’ characteristics, such as gender, education, and attitude towards fruits and vegetables, and (2) daily amount of fruits and vegetables eaten by the child, and the child’s gender and age.

Research has recognized gender as moderating consumption and behavior intention [62,63]. The results of our study show that mothers and fathers had a similar intention to provide fruits and vegetables to their children (MMother = 5.27; MFather = 5.05; F (1289) = 0.67; p > 0.1), but, as expected, women were more sensitive to emotional framing compared to men (MMother = 5.61; MFather = 4.71; F (1149) = 5.55; p < 0.05). On the other hand, although men appeared to be more persuaded by rational messages versus women, the difference was not significant (MMother = 4.87; MFather = 5.33; F (1137) = 1.56; p > 0.1). Surprisingly, the difference in the influence of celebrity classified by gender was zero (MMother = 4.99; MFather = 4.94; F (1136) = 0.18; p > 0.1)—in other words, George Clooney was found to be accepted as a celebrity by women and men equally. Table 2 shows the results regarding parents’ intention to provide fruits and vegetables across the conditions, with standard deviations in parentheses.

Table 2.

Means of parental intention to provide fruit and vegetables to children.

Most of the control variables did not make a significant difference in parental intentions to provide fruits and vegetables to their children. The only two covariates that increased the fit of the proposed model were children’s age and parents’ attitude toward fruits and vegetables. Thus, we ran the final ANCOVA with only these two covariates (see Table 3).

Table 3.

ANCOVA for dependent variable parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables to their children.

The results showed that parental attitude toward fruits and vegetables exerted a significant effect on their intention to provide fruits and vegetables to their children (F(1289) = 63.23; p < 0.000). Correlation analysis (r = 0.45; p < 0.00) indicated that the higher the parental attitudes toward fruits and vegetables, the higher their intention to provide fruits and vegetables to their children.

We also found a significant main effect of the type of endorser. As predicted in H1, the parents’ intention to provide fruits and vegetables to their children was higher when parents were exposed to the ad with the expert endorser (Dr. Marshall) than when they were exposed to the ad with the celebrity endorser (George Clooney): (MCelebrity = 4.98; MExpert = 5.43; F (1289) = 4.11; p < 0.05).

Additionally, the valence of the message revealed, as predicted in H2, a significant main effect. Parents’ intention to provide fruits and vegetables to their children was higher for parents who were exposed to the ad with a positive message than for those who were exposed to that with a negative one (MNegative = 4.98; MPositive = 5.42; F (1289) = 3.89; p < 0.05).

The emotional/rational message framing also revealed a significant main effect. The dependent variable, parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables to their children, was higher for parents who were exposed to the rational ad than for those that were exposed to the emotional one (MEmotional = 5.44; MRational = 4.98; F (1289) = 4.16; p < 0.05).

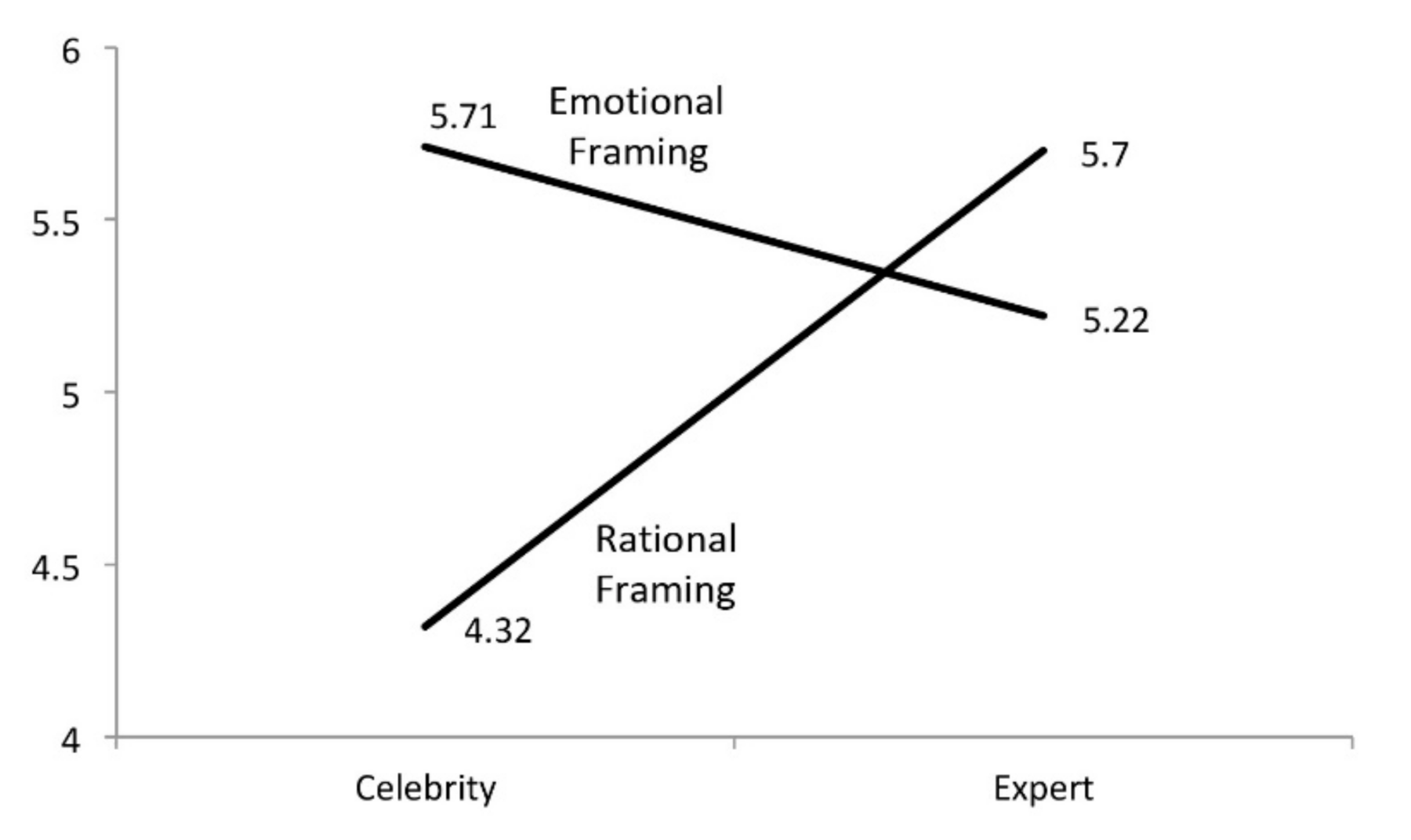

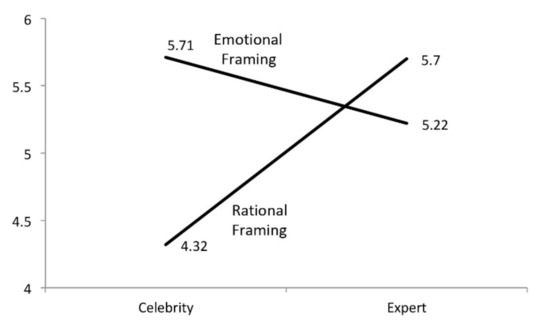

Additionally, we found a highly significant interaction effect between the celebrity/expert endorser and the emotional/rational message framing (F (1289) = 12.60; p < 0.000), which confirms H4. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Interaction effect of attractive/expert endorser and emotional/rational message framing on parent’s intention to provide fruits and vegetables to their children.

Figure 2 shows that when we used an expert endorser there was no difference depending on whether the message was emotional or rational (MEmotional = 5.22; MRational = 5.70; F (1149) = 2.34; p > 0.10)—that is, the tone of the framing was not relevant. On the other hand, when the endorser was celebrity, emotional framing was associated with a higher parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables to their children (MEmotional = 5.71; MRational = 4.32; F (1136) = 21.85; p < 0.000), compared to using a rational framing.

We can also see that if the message framing was emotional, the message endorser was irrelevant (MCelebrity = 5.71; MExpert = 5.22; F(1149) = 2.49; p > 0.10); however, if the message framing was rational there was a significant difference between the celebrity endorser and the expert endorser (MCelebrity = 4.32; MExpert = 5.70; F (1150) = 2.34; p > 0.10). Thus, parents found the rational message more credible, and therefore more persuasive, when it was endorsed by the doctor rather than the actor.

However, no interaction was found between the celebrity/expert endorser and the negative/positive message framing (F (1289) = 0.13; p > 0.1), or between the negative/positive and emotional/rational message framings (F (1289) = 0.53; p > 0.1). The triple interaction effect was also not significant (F (1289) = 0.02; p > 0.1). The adjusted R-squared value for the complete model was 0.251.

5. Discussion and Recommendations

Our research stemmed from the idea that changing parental attitudes toward giving fruits and vegetables to their children can mitigate the issue of childhood obesity. Our intention was to define a standard for communications to parents regarding the importance of providing children with more fruits and vegetables, which will ideally increase children’s consumption of these foods.

Parenting practices, such as pressure, restriction, modeling, and availability, influence their children’s eating patterns [64]. Thus, parents’ degree of awareness and level of concern and commitment toward healthy habits should have a strong influence on their own behavior, and in turn have a positive influence via modeling on their children’s habits [65]. Specifically, we considered how to improve communication to parents in order to change their attitudes toward giving fruits and vegetables to their children.

Our findings show that parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables is influenced by the message endorser, with the effect found to be higher for the expert endorser than for the celebrity one. This result is consistent with those found by Pornpitakpan [66], who indicated that higher source credibility results in greater persuasion in terms of both attitudinal and behavioral measures. The trustworthiness and the expertise dimensions of source credibility contribute to this effect on parental intentions.

Our research also contributes to the literature on social marketing by examining the effectiveness of campaigns targeted toward changing parents’ attitudes. It extends prior studies on health communications to the domain of message framing, specifically concerning the valence of the message in prevention-focused health communications [67]. The results show that positive messages have a greater and more significant main effect on intention to provide fruits and vegetables versus negative messages. This is in line with the idea that messages that evoke positive emotions may have a greater impact on the target group versus those evoking negative emotions, such as fear [44].

We also extend prior research findings to the domain of emotional and rational message framing. In our study, the emotional message framing had a greater effect on parental intention to provide fruits and vegetables than the rational message framing. This means that, for most parents, the wellbeing of their children is one of their central drivers, and is an emotional feeling rather than a rational one. When parents receive an emotional message, their cognition will be more consistent with their relationship with their children versus when the message is rational; therefore, the persuasion from the emotional message will be higher than that from the rational one.

The significant interaction effect between the celebrity/expert endorser and the emotional/rational framing means that the celebrity endorser sounds emotional, while the expert appears indifferent. In summary, increasing parental intention to give fruits and vegetables to their children is based on the consideration of three variables: the endorser, the valence, and the emotional/cognitive dimension of the message. We found no significant difference in the mean of intention to provide fruits versus the mean of the intention to provide vegetables. Therefore, as far as this research is concerned, fruits and vegetables can be considered together despite the slight behavior differences that might be expected.

In addition to these contributions to marketing literature, this research has important implications for policy-makers and managers. Policy-makers in charge of public health have huge responsibilities, since health is one of the top priorities for most citizens and, therefore, for voters. Good health can be achieved via two means: prevention and cure. As a general rule, prevention is less expensive than cure, and in many Western societies budgets for the public health system are rising rapidly. Therefore, health policy-makers should focus on fighting causes of illness in order to attain the maximum results with the minimum budget. Furthermore, we provide significant insights into how communication campaigns should be designed in order to promote parental intention to give more fruits and vegetables to their children. The endorser should be an expert and the message should be positive and emotional, while rational messages endorsed by celebrities should be avoided. In summary, our contribution can make a significant difference in terms of increasing efficiency and reducing costs when designing campaigns that encourage children to eat more fruits and vegetables through targeting parents.

Future research related to communication design when promoting the consumption of fruits and vegetables can extend our study in three main ways. First, while we found significant results in the experiment, the limited sample prevented us generalizing the results. In order to compensate this limitation, future studies may use national representative samples. Second, our ad combined fruits and vegetables in the same message. Therefore, new studies may consider replication with an exclusive ad for fruits and another for vegetables to check whether results are the same. Finally, some celebrities may now be considered as experts, as may be the case with influencers, and new studies may consider this as a third condition to complement the celebrity/expert duality included in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.G.-C.; L.M. and S.R.D.M.; methodology, M.G.G.-C.; L.M. and S.R.D.M.; formal analysis M.G.G.-C.; investigation, M.G.G.-C.; resources, L.M. and S.R.D.M.; writing M.G.G.-C.; L.M. and S.R.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Cátedra RSC Universidad de Murcia.

Acknowledgments

L.M. and S.R. want to thank Miguel Giménez for the lessons about the life he gave them during the development of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Sun, S.; Hea, J.; Shen, B.; Fan, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, X. Obesity as a “self-regulated epidemic”: Coverage of obesity in Chinese newspapers. Eat. Weight. Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, M.; Crow, S. Parents Are Key Players in the Prevention and Treatment of Weight-related Problems. Nutr. Rev. 2004, 62, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracia-Marco, L.; Vicente-Rodríguez, G.; Borys, J.M.; Le Bodo, Y.; Pettigrew, S.; Moreno, L.A. Contribution of social marketing strategies to community-based obesity prevention programmes in children. Int. J. Obes. 2010, 35, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubacki, K.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Lahtinen, V.; Parkinson, J. A systematic review assessing the extent of social marketing principle use in interventions targeting children (2000–2014). Young Consum. 2015, 16, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, C.A.; Ravia, J. A Systematic Review of Behavioral Interventions to Promote Intake of Fruit and Vegetables. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 1523–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anzman, S.L.; Rollins, B.Y.; Birch, L.L. Parental Influence on Children’s Early Eating Environments and Obestiry Risk: Implications for Prevention. Int. J. Obes. 2010, 34, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, S.; Pescud, M. Improving parents’ child-feeding practices: A social marketing challenge. J. Soc. Mark. 2012, 2, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davó-Blanes, M.C.; Ortiz-Moncada, R.; Gil-González, D.; Álvarez-Dardet, C.; Lobstein, T. The impact of marketing practices and its regulation policies on childhood obesity. Opinions of stakeholders in Spain. Appetite 2013, 62, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, G.J.; Zambrano, R.E.; Galiano-Coronil, A.; Ravina-Ripoll, R. Food and Beverage Advertising Aimed at Spanish Children Issued through Mobile Devices: A Study from a Social Marketing and Happiness Management Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobey, L.; Koenig, H.F.; Brown, N.A.; Manore, M.M. Reaching Low-Income Mothers to Improve Family Fruit and Vegetable Intake: Food Hero Social Marketing Campaign—Research Steps, Development and Testing. Nutrients 2016, 8, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blitstein, J.L.; Cates, S.C.; Hersey, J.; Montgomery, D.; Shelley, M.; Hradek, C.; Kosa, K.; Bell, L.; Long, V.; Williams, P.A.; et al. Adding a Social Marketing Campaign to a School-Based Nutrition Education Program Improves Children’s Dietary Intake: A Quasi-Experimental Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1285–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettigrew, S. Pleasure: An under-utilised ‘P’ in social marketing for healthy eating. Appetite 2016, 104, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, C.G.; Worsley, A.; Liem, D.G. Parents’ food choice motives and their associations with children’s food preferences. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 18, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeinstra, G.G.; Koelen, M.A.; Kok, F.J.; Van Der Laan, N.; De Graaf, C. Parental child-feeding strategies in relation to Dutch children’s fruit and vegetable intake. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 13, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bere, E.; Klepp, K.-I. Changes in accessibility and preferences predict children’s future fruit and vegetable intake. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2005, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, H.; Pealing, J.; Hayter, A.K.; Pettinger, C.; Pikhart, H.; Watt, R.G.; Rees, G. Parental food involvement predicts parent and child intakes of fruits and vegetables. Appetite 2013, 69, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, N.; Biddle, S.J.H.; Gorely, T. Family correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjansdottir, A.G.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Klepp, K.-I.; Thorsdottir, I. Children’s and parents’ perceptions of the determinants of children’s fruit and vegetable intake in a low-intake population. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, C.; Meurer, C.; Simmonds, J.; Snell, T. Anti-obesity public health messages and risk factors for disordered eating: A systematic review. Health Promot. Int. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persky, S.; Ferrer, R.A.; Klein, W.M.P.; Goldring, M.R.; Cohen, R.W.; Kistler, W.D.; Yaremych, H.E.; Bouhlal, S. Effects of Fruit and Vegetable Feeding Messages on Mothers and Fathers: Interactions Between Emotional State and Health Message Framing. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018, 53, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabashkina, L.; Quester, P.G.; Crouch, R.; Lee, N.; Carrillat, F. Children and energy-dense foods—Parents, peers, acceptability or advertising? Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 1669–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaña, M.; Morales, M.J. Soft Drinks and Sugar-Sweetened Beverages Advertising in Spain: Correlation between Nutritional Values and Advertising Discursive Strategies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noar, S.M. A 10-Year Retrospective of Research in Health Mass Media Campaigns: Where Do We Go From Here? J. Health Commun. 2006, 11, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980; Volume 278. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen, A.R. Marketing Social Change: Changing Behavior to Promote Health, Social Development, and the Environment; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Roberto, E. Social Marketing: Strategies for Changing Public Behavior; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, W. Theoretical Foundations of Campaigns; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1981; pp. 41–70. [Google Scholar]

- Manoff, R. Social Marketing: New Imperative for Public Health; Preeger: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Shimp, T. Advertising, Promotion, and Supplemental Aspects of Integrated Marketing Communications; Harcourt Brace College Publishers: San Diego, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, A. Involuntary Attention and Physiological Arousal Evoked by Structural Features and Emotional Content in TV Commercials. Commun. Res. 1990, 17, 275–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlo, D.K.; Lemert, J.B.; Mertz, R.J. Dimensions for Evaluating the Acceptability of Message Sources. Public Opin. Q. 1969, 33, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.I.; Weiss, W. The Influence of Source Credibility on Communication Effectiveness. Public Opin. Q. 1951, 15, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, J.E.; Rogers, W. Effects of source expertness, physical attractiveness, and supporting arguments on persuasion: A case of brains over beauty. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and Validation of a Scale to Measure Celebrity Endorsers’ Perceived Expertise, Trustworthiness, and Attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B.Z. Celebrity Endorsement: A Literature Review. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B.Z. Reasons for using celebrity endorsement. Admap Mag. 2005, 459, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Amos, C.; Holmes, G.; Strutton, D. Exploring the relationship between celebrity endorser effects and advertising effectiveness. Int. J. Advert. 2008, 27, 209–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callcott, M.F.; Phillips, B.J. Observations: Elves make good cookies: Creating likable spokes-character advertising. J. Advert. Res. 1996, 36, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Horai, J.; Naccari, N.; Fatoullah, E. The Effects of Expertise and Physical Attractiveness Upon Opinion Agreement and Liking. Sociometry 1974, 37, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 1981, 211, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothman, A.; Salovey, P. Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behavior: The role of message framing. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 121, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petty, R.; Cacioppo, J.T. Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, K.M.; Updegraff, J.A. Health Message Framing Effects on Attitudes, Intentions, and Behavior: A Meta-analytic Review. Ann. Behav. Med. 2011, 43, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monahan, J. Thinking Positively: Using Positive Affect when Designing Health Messages; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hovland, C.; Janis, I.; Kelley, H. Communication and Persuasion; Psychological Studies of Opinion Change; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, O. How Emotional Tugs Trump Rational Pushes: The Time Has Come to Abandon a 100-Year-Old Advertising Model. J. Advert. Res. 2012, 52, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Fakharyan, M.; Dadkhah, R.; Khodadadian, M.R.; Vosta, S.N.; Jafari, M. Investigating the Effect of Rational and Emotional Advertising Appeals of Hamrahe Aval Mobile Operator on Attitude towards Advertising and Brand Attitude (Case Study: Student Users of Mobile in the Area of Tehran). Int. J. Asian Soc. Sci. 2015, 5, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelis, E.; Adams, L.; Cauberghe, V. The Effectiveness of Emotional and Rational Regulatory (In)congruent Messages for a Fair Trade Campaign. Adv. Advert. Res. 2011, 2, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J.; Harter, M. Parent-Child Relationships. In Crosscurrents in Contemporary Psychology. Well-Being: Positive Development across the Life Course; Bornstein, M.H., Davidson, L., Keyes, C.L.M., Moore, K.A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Stiff, J.B.; Mongeau, P.A. Persuasive Communication; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones, E. A Cognitive Dissonance Theory Perspective on Persuasion. In The Persuasion Handbook: Developments in Theory and Practice; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Machleit, K.A.; Allen, C.T.; Madden, T.J. The Mature Brand and Brand Interest: An Alternative Consequence of Ad-Evoked Affect. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feick, L.; Higie, R.A. The Effects of Preference Heterogeneity and Source Characteristics on Ad Processing and Judgments about Endorsers. J. Advert. 1992, 21, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheswaran, D.; Meyers-Levy, J. The Influence of Message Framing and Issue Involvement. J. Mark. Res. 1990, 27, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, L.L.; Fisher, J.; Grimm-Thomas, K.; Markey, C.; Sawyer, R.; Johnson, S. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: A measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite 2001, 36, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emanuel, A.S.; McCully, S.N.; Gallagher, K.M.; Updegraff, J.A. Theory of Planned Behavior explains gender difference in fruit and vegetable consumption. Appetite 2012, 59, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanck, H.M.; Gillespie, C.; Kimmons, J.E.; Seymour, J.D.; Serdula, M.K. Trends in fruit and vegetable consumption among US men and women, 1994–2005. Preven. Chronic Dis. 2008, 5, A35. [Google Scholar]

- Lehto, E.; Ray, C.; Velde, S.T.; Petrova, S.; Duleva, V.; Krawinkel, M.; Behrendt, I.; Papadaki, A.; Kristjansdottir, A.; Thorsdottir, I.; et al. Mediation of parental educational level on fruit and vegetable intake among schoolchildren in ten European countries. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 18, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, M.; Krølner, R.; Klepp, K.-I.; Lytle, L.A.; Brug, J.; Bere, E.; Due, P. Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents: A review of the literature. Part I: Quantitative studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2006, 3, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Silva, A.; Sánchez-García, M.; Nunes, C.; Martins, A. Gender differences in condom use prediction with Theory of Reasoned Action and Planned Behaviour: The role of self-efficacy and control. AIDS Care 2007, 19, 1177–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, L.; Morgan, M.S. Trend Effects and Gender Differences in Retrospective Judgments of Consumption Emotions. J. Consum. Res. 1996, 23, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, A.K.; Birch, L.L. Does parenting affect children’s eating and weight status? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaglioni, S.; Salvioni, M.; Galimberti, C. Influence of parental attitudes in the development of children eating behaviour. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, S22–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pornpitakpan, C. The Persuasiveness of Source Credibility: A Critical Review of Five Decades’ Evidence. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 243–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaña, M.; Morales, M.J.; Vàzquez, M. Food Advertising and Prevention of Childhood Obesity in Spain: Analysis of the Nutritional Value of the Products and Discursive Strategies Used in the Ads Most Viewed by Children from 2016 to 2018. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).