Developing a Wine Experience Scale: A New Strategy to Measure Holistic Behaviour of Wine Tourists

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review: Wine Tourism Experience and the Domain of Constructs

2.1. Wine Tourism Experience

2.2. Wine Excitement

2.3. Wine Sensory Appeal

2.4. Winescape

2.5. Wine Storytelling

2.6. Wine Involvement

3. Research Method

3.1. Scale Development Process

3.2. Item Generation

3.3. Purifying the Measurement

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Sample Profile

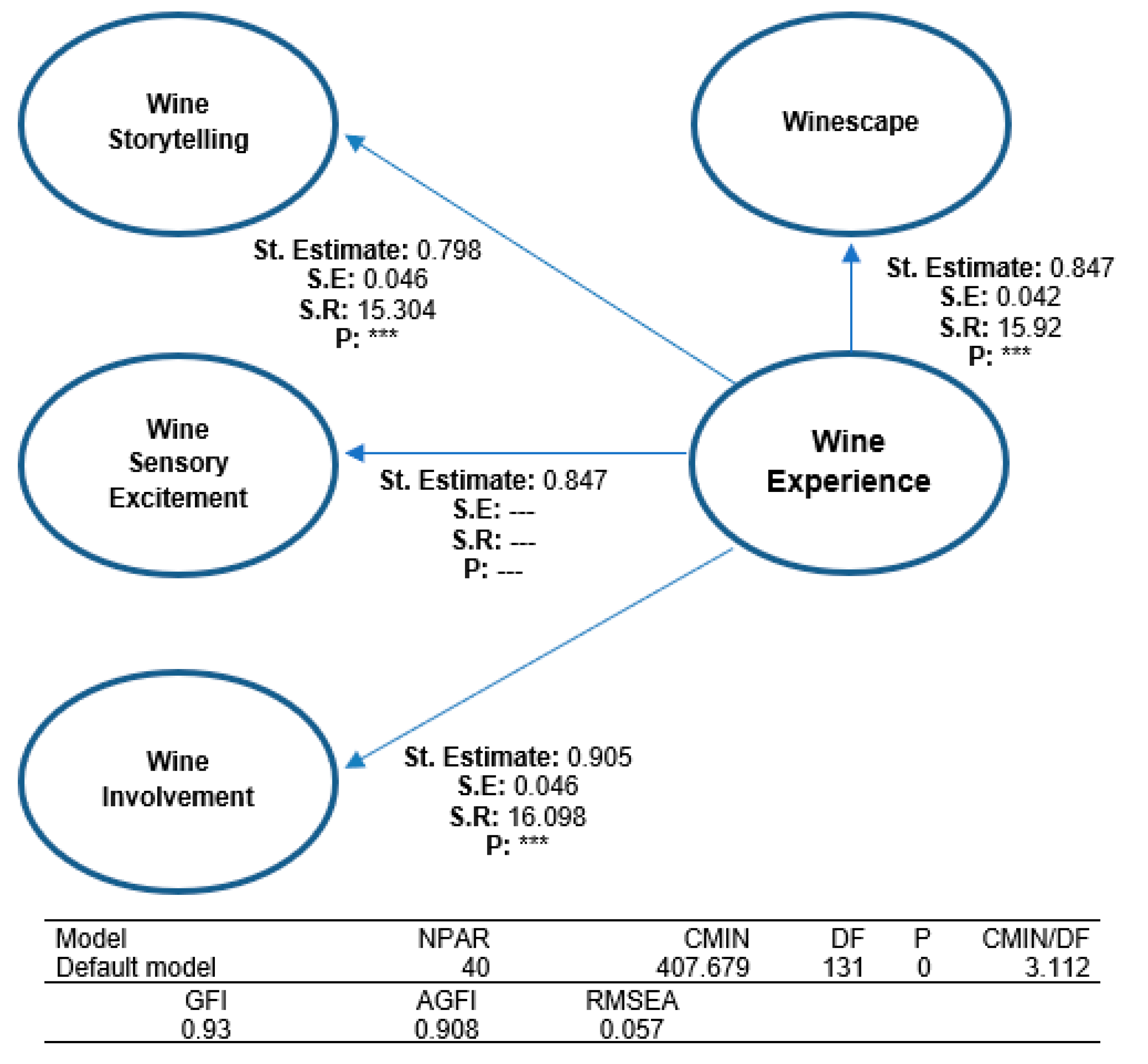

4.2. Finalising the Measurement

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- INE. Estatísticas do Turismo—2019; INE: Lisbon, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Turismo de Portugal. Turismo em Portugal—Visão Geral 2020. Available online: http://www.turismodeportugal.pt/pt/Turismo_Portugal/visao_geral/Paginas/default.aspx (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Thanh, T.V.; Kirova, V. Wine tourism experience: A netnography study. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 83, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIV. Statistical Report on World Vitiviniculture 2019. Available online: http://oiv.int/public/medias/6782/oiv-2019-statistical-report-on-world-vitiviniculture.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- IVDP 2020. Available online: https://www.ivdp.pt/consumidor/vendas-de-vinho-do-porto (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Madeira Wine, 2019, 2020. Available online: https://vinhomadeira.com/storage/uploads/statistics/variao-homloga-2019---2020-mercado-comercializao-de-vinho-da-madeira-por-mercado5f297f4254a1a.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Bruwer, J.; Rueger-Muck, E. Wine tourism and hedonic experience: A motivation-based experiential view. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 19, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, A.; Correia, A.; Filipe, J. Modelling wine tourism experiences. Anatolia 2019, 30, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Sharples, L.; Cambourne, B.; Macionis, N. Wine Tourism around the World; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J. A Model of Wine Tourist Behavior: A Festival Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, Indiana Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, B. Planning a wine tourism vacation? Factors that help to predict tourist behavioural intentions. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1180–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bruwer, J. South African wine routes: Some perspective on the wine tourism industry’s structural dimensions and wine tourism product. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, T.H.; Yuan, J.; Adams, C.; Kolesnikova, N. Motivations of young people for visiting wine festivals. Event Manag. 2006, 10, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, B.; Quintal, V.; Phau, I. Wine Tourist Engagement with the Winescape: Scale Development and Validation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2016, 42, 793–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.M.G.; Santos, V.R.; Almeida, N. Main challenges, trends and opportunities for wine tourism in Portugal. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S.; Fountain, J.; Fish, N. “You Felt Like Lingering...” Experiencing “Real” Service at the Winery Tasting Room. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brás, J.M.; Costa, C.; Buhalis, D. Network analysis and wine routes: The case of the Bairrada Wine Route. Serv. Ind. J. 2010, 30/10, 1621–1641. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, V.; Almeida, N.; Santos-Pavón, E. Wine and wine tourism experience: A theoretical and conceptual review. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2019, 11, 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachão, S.; Breda, Z.; Fernandes, C.; Joukes, V. Food-and-wine experiences towards co-creation in tourism. Tour. Rev. 2020. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Cai, L.; Morrison, A.M.; Linton, S. A Model of Wine Tourist Behaviour: A Festival Approach. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 10, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S.; Ali-Knight, J. Who is the wine tourist? Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, B.; Peters, M.; Boksberger, P.; Secco, M. The Staging of Experiences in Wine Tourism. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Alant, K. The hedonic nature of wine tourism consumption: An experiential view. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garibaldi, R.; Pozzi, A. Creating tourism experiences combining food and culture: An analysis among Italian producers. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leri, I.; Theodoridis, P. The effects of the winery visitor experience on emotions, satisfaction and on post-visit behaviour intentions. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 480–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leri, I.; Theodoridis, P. How do personality traits affect visitor’s experience, emotional stimulation and behaviour? The case of wine tourism. Tour. Rev. 2020. in-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Hall, C.M. Wine Tourism Research: The State of Play. Tour. Rev. Int. 2006, 9, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festa, G.; Vrontis, D.; Thrassou, A.; Ciasullo, M.V. A value co-creation model for wine tourism. Int. J. Manag. Pract. 2015, 8, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadri-Felitti, D.; Fiore, A. Experience economy for understanding wine tourism. J. Vacat. Mark. 2012, 18, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.; Pratt, M.A.; Molina, A. Wine tourism research: A systematic review of 20 vintages from 1995 to 2014. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 22, 2211–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, D. Food, the Body and Self; Sage: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, K. Demand for the gastronomy tourism product: Motivational factors. In Tourism and Gastronomy; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; pp. 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.G.; Eves, A.; Scarles, C. Building a model of local food consumption on trips and holidays: A grounded theory approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urry, J. The Tourist Gaze, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Trauer, B.; Ryan, C. Destination image, romance and place experience—An application of intimacy theory in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Eves, A. Construction and Validation of a Scale to Measure Tourist Motivation to Consume Local Food. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1458–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Su, S.; Chiang, C. Dual attractiveness of winery: Atmospheric cues on purchasing. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2008, 20, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, A.M.; Tasci, A. Customer experience in tourism: A review of definitions, components, and measurements. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapito, D.; Pinto, D.; Mendes, J. Tourists’ memories, sensory impressions and loyalty: In loco and post-visit study in Southwest Portugal. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, R.; Go, F.; Kumar, K. Virtual destination image: A new measurement approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 977–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Ryan, S. Tourism sense-making: The role of the senses and travel journalism. Travel Tour. Mark. 2009, 26, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A.; Stoleriu, O.; Lupu, C. Wine tourism: A multisensory experience. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, T.; Gustafson, A. Product, environmental, and service attributes that influence consumer attitudes and purchases at wineries. J. Food Prod. Mark. 1997, 4, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzdine-Chameeva, T.; Durrieu, F. A sense of place in wine tourism: Differences between local and non-local visitors in Bordeaux region. In Proceedings of the 6th AWBR International Conference, Bordeaux Management School, BEM, Bordeaux, France, 9–10 June 2011; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ali-Knight, J.; Carlsen, J. An Exploration of the use of “Extraordinary” Experiences in Wine Tourism. In Proceeding of the International Colloquium in Wine Marketing; Wine Marketing Group, University of South Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2003; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.; Bruwer, J. Regional brand image and perceived wine quality: The consumer perspective. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2007, 19, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alebaki, M.; Lakovidou, O. Market segmentation in wine tourism: A comparison of approaches, Tourismos. Int. Multidiscip. J. Tour. 2011, 6, 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Bruwer, J.; Lesschaeve, I. Wine tourists’ destination region brand image perception and antecedents: Conceptualisation of a winescape framework. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B.P. Wine tourist motivation and the perceived importance of servicescape: A study conducted in Goa, India. Tour. Rev. 2006, 61, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Gross, M.J. A Multilayered Macro Approach to Conceptualizing the Winescape Construct for Wine Tourism. Tour. Anal. 2017, 22, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. The Shaping of Tourist Experience: The Importance of Stories and Themes; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2010; pp. 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, M.; Charters, S. Service quality at the cellar door: Implications for Western Australia’s developing wine tourism industry. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2000, 10, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, P.; Livat, F. Does storytelling add value to fine Bordeaux wines? Wine Econ. Policy 2013, 2, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bach, K. Talk about Wine? Wine and Philosophy. A Symposium on Thinking and Drinking; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, P.; Moscarola, J. Representations of the emotions associated with a wine purchasing or consumption experience. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 34, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Brown, G. Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.P.; Havitz, M.; Getz, G. Relationship between wine involvement and wine-related travel. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2007, 21, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, N.; Ismail, J.; Dodd, T. Purchase attributes of wine consumers with low involvement. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2007, 14, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Cai, L.; Morrison, A.; Linton, S. An analysis of wine festival attendees’ motivations: A synergy of wine, travel and special events? J. Vacat. Mark. 2005, 11, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E.; Chiappa, G.D.; Coudounaris, D.; Björk, P. Tourism experiences, memorability and behavioural intentions: A study of tourists in Sardinia, Italy. Tour. Rev. 2019, 75, 533–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santos, V.; Caldeira, A.; Santos, E.; Oliveira, S.; Ramos, P. Wine Tourism Experience in the Tejo Region: The influence of sensory impressions on post-visit behaviour intentions. Int. J. Mark. Commun. New Media, Special Issue 5—Tourism Marketing 2019, 54–75. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, G. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. 1979, 16, 4–73. [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer, R.; Bearden, W.; Sharma, S. Scaling Procedures: Issues and Applications; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Moore, M. Confirmatory factor analysis. In Handbook of Structural Equation Modelling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 361–379. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, B.; Babin, R.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Eves, A.; Scarles, C. Empirical verification of a conceptual model of local food consumption at a tourist destination. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential Marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, D.; Gilmore, J. The Experience Economy; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Shin, W. Marketing tradition-bound products through storytelling: A case study of a Japanese sake brewery. Serv. Bus. 2014, 9, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ben-Nun, L.; Cohen, E. The perceived importance of the features of wine regions and wineries for tourists in wine regions. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference of the Academy of Wine Business Research, Siena, Italy, 17–19 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.; Gerbing, D. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 10, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garver, M.; Mentzer, J. Logistics research methods: Employing structural equation modeling to test for construct validity. J. Bus. Logist. 1999, 20, 33–57. [Google Scholar]

- Asero, V.; Patti, S. From Wine Production to Wine Tourism Experience: The Case of Italy; American Association of Wine Economists, Economic Department, New York University: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, J.; Gonçalves, R.; Branco, F.; Barbosa, L.; Melo, M.; Bessa, M. A multisensory virtual experience model for thematic tourism: A Port wine tourism application proposal. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M.; Robinson, R. Wine Tourism Destination Management and Marketing; Palgrave: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Terziyska, I. Wine Tourism: Critical Success Factors for an Emerging Destination; Gea-Libris: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, C. Tourism planning: A perspective paper. Tour. Rev. 2019, 75, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço-Gomes, L.; Pinto, L.M.; Rebelo, J. Wine and cultural heritage. The experience of the Alto Douro Wine Region. Wine Econ. Policy 2015, 4, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Canziani, B.F. Wine Tourism: Balancing Core Product and Service-Dominant Strategies in Wine Tourism Destination Management and Marketing; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Boatto, V.; Galletto, L.; Barisan, L.; Bianchin, F. The development of wine tourism in the Conegliano Valdobbiadene area. Wine Econ. Policy 2013, 2, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions | Scale Items Adjusted to Wine Experience | Support References |

|---|---|---|

| Wine Tasting Excitement | 1. Tasting this wine in its original wine cellars makes me excited 2. Tasting this wine on holidays helps me to relax 3. Tasting this wine makes me feel exhilarated 4. Tasting this wine on holidays makes me stop worrying about routine | [41,67,68]. |

| Winescape | 5. This winery landscape has a rural appeal 6. These buildings have historic appeal 7. There is an old-world charm in these wine cellars 8. This architecture gives the winery character | [14,23,56,68,69]. |

| Wine Storytelling | 9. Stories told about the wine positively influenced the value I attribute to it 10. Stories told about the wine positively influenced the value I attribute to the wine tasting 11. Stories told about the wine positively influenced the value I attribute to this visit 12. Stories told about the wine enabled me to have an enjoyable time 13. Stories told about the wine enabled me to learn ancient facts about wine that I did not know | [53,54,70]. |

| Wine Involvement | 14. I like to purchase wine to match the occasion 15. For me, drinking this wine gives me pleasure 16. I enjoyed these wine activities which I really wanted to do 17. For me, these wine tastings are a particularly pleasurable experience 18. My interest in this wine makes me want to visit these wine cellars | [57,71]. |

| Dimensions and Items | Factor Loading | Mean | SD | Total Variance Explained (%) | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wine Tasting Excitement | - | - | - | 16.662 | 0.887 |

| 1. Tasting this wine in its original wine cellars makes me excited | 0.697 | 6.23 | 1.074 | - | - |

| 2. Tasting this wine on holidays helps me to relax | 0.688 | 5.90 | 1.281 | - | - |

| 3. Tasting this wine makes me feel exhilarated | 0.725 | 5.91 | 1.256 | - | - |

| 4. Tasting this wine on holidays makes me stop worrying about routine | 0.658 | 5.88 | 1.414 | - | - |

| Wine Storytelling | - | - | - | 15.952 | 0.888 |

| 1. Stories that the wine tour guide/winemaker/wine producer told about the wine positively influenced the value I attribute to the wine | 0.819 | 6.30 | 1.014 | - | - |

| 2. Stories that the wine tour guide/winemaker/wine producer told about the wine positively influenced the value I attribute to the wine tasting | 0.770 | 6.15 | 0.977 | - | - |

| 3. Stories that the wine tour guide/winemaker/wine producer told about the wine positively influenced the value I attribute to this visit | 0.703 | 6.21 | 0.882 | - | - |

| 4. Stories that the wine tour guide/winemaker/wine producer told about the wine enabled me to have an enjoyable time | 0.689 | 6.22 | 0.916 | - | - |

| 5. Stories that the wine tour guide/winemaker/wine producer told about the wine enabled me to learn ancient facts about wine that I did not know | 0.691 | 6.30 | 1.029 | - | - |

| Wine Involvement | - | - | - | 14.442 | 0.876 |

| 1. I like to purchase wine to match the occasion | 0.626 | 6.16 | 1.071 | - | - |

| 2. For me, drinking this wine gives me pleasure | 0.677 | 6.33 | 0.886 | - | - |

| 3. I enjoyed these wine activities which I really wanted to do | 0.689 | 6.19 | 0.926 | - | - |

| 4. For me, these wine tastings are a particularly pleasurable experience | 0.699 | 6.34 | 0.857 | - | - |

| 5. My interest in this wine makes me want to visit these wine cellars | 0.534 | 6.27 | 1.012 | - | - |

| Winescape | - | - | - | 11.880 | 0.793 |

| 1. This winery landscape has a rural appeal | 0.570 | 6.20 | 1.017 | - | - |

| 2. These buildings have historic appeal | 0.642 | 6.40 | 0.846 | - | - |

| 3. There is an old-world charm in these wine cellars | 0.705 | 6.27 | 0.868 | - | - |

| 4. This architecture gives the winery character | 0.585 | 6.32 | 0.855 | - | - |

| Gender | Age | Education Level | Country of Origin | Job |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (49.7%) | 18–24 years old (7.1%) | Less than high school graduate (3.7%) | Portugal (8.3%) Spain (5.6%) | Businessperson/manager (16%) Freelancer/self-employed (17.9%) |

| Female (50.3%) | 25–34 years old (21.3%) 35–44 years old (21%) 45–54 years old (27.8%) 55–64 years old (16%) 65 or > years old (6.8%) | High school graduate (18.5%) Degree (43.8%) Master’s degree (27.2%) Doctorate (6.8%) | France (24.7%) Germany (7.7%) United Kingdom (25.9%) Other countries (27.8%) | Middle/senior employed management (17%) Civil servant (11.4%) Worker (17.4%) Pensioner/retired (4%) Domestic/unemployed (1.5%) Student (6.5%) Other (8.3%) |

| Constructs and Indicators | St. Regression | S.E. | C.R. | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stories that the wine tour guide/winemaker/wine producer told about the wine enabled me to learn ancient facts about wine that I did not know | <--- | Wine Storytelling | 0.798 | - | - | - |

| Stories that the wine tour guide/winemaker/wine producer told about the wine enabled me to have an enjoyable time | <--- | Wine Storytelling | 0.848 | 0.042 | 23.778 | *** |

| Stories that the wine tour guide/winemaker/wine producer told about wine positively influenced the value I attribute to this visit | <--- | Wine Storytelling | 0.826 | 0.044 | 22.402 | *** |

| Stories that the wine tour guide/winemaker/wine producer told about the wine positively influenced the value I attribute to the wine tasting | <--- | Wine Storytelling | 0.88 | 0.05 | 22.376 | *** |

| Stories that the wine tour guide/winemaker/wine producer told about the wine positively influenced the value I attribute to the wine | <--- | Wine Storytelling | 0.891 | 0.045 | 25.063 | *** |

| Tasting this wine on holidays makes me stop worrying about routine | <--- | Wine Tasting Excitement | 0.84 | - | - | - |

| Tasting this wine makes me feel exhilarated | <--- | Wine Tasting Excitement | 0.808 | 0.046 | 23.441 | *** |

| Tasting this wine on holidays helps me to relax | <--- | Wine Tasting Excitement | 0.874 | 0.043 | 25.592 | *** |

| Tasting this wine in its original wine cellars makes me excited | <--- | Wine Tasting Excitement | 0.79 | 0.035 | 22.06 | *** |

| My interest in this wine makes me want to visit these wine cellars | <--- | Wine Involvement | 0.773 | - | - | - |

| For me, these wine tastings are a particularly pleasurable experience | <--- | Wine Involvement | 0.846 | 0.044 | 21.931 | *** |

| I enjoyed these wine activities which I really wanted to do | <--- | Wine Involvement | 0.833 | 0.05 | 21.069 | *** |

| For me, drinking this wine gives me pleasure | <--- | Wine Involvement | 0.837 | 0.048 | 20.021 | *** |

| I like to purchase wine to match the occasion | <--- | Wine Involvement | 0.841 | 0.056 | 21.02 | *** |

| This winery landscape has a rural appeal | <--- | Winescape | 0.75 | - | - | - |

| These buildings have historic appeal | <--- | Winescape | 0.78 | 0.052 | 17.594 | *** |

| There is an old-world charm in these wine cellars | <--- | Winescape | 0.805 | 0.056 | 17.29 | *** |

| This architecture gives the winery character | <--- | Winescape | 0.82 | 0.055 | 17.62 | *** |

| Dimensions | CR | AVE | MSV | ASV | Wine Involvement | Wine Storytelling | Wine Tasting Excitement | Winescape |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wine Involvement | 0.915 | 0.683 | 0.594 | 0.570 | 0.826 | - | - | - |

| Wine Storytelling | 0.928 | 0.721 | 0.527 | 0.479 | 0.726 | 0.849 | - | - |

| Wine Tasting Excitement | 0.897 | 0.687 | 0.594 | 0.537 | 0.771 | 0.690 | 0.829 | - |

| Winescape | 0.868 | 0.623 | 0.590 | 0.521 | 0.768 | 0.659 | 0.735 | 0.789 |

| GOF Indexes | - | X2 | Df | p-value | X2/df | GFI | AGFI | RMSEA |

| Whole sample (n = 647) | - | 406.302 | 129 | *** | 3.15 | 0.93 | 0.907 | 0.058 |

| Dimensions and Constructs | - | Porto Wine Cellars | Madeira Wine Cellars | - | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | - | Estimate | p | Estimate | p | z-Score |

| Wine Storytelling | <--- | Wine Experience | 0.574 | *** | 0.718 | *** | 1.72 * |

| Wine Involvement | <--- | Wine Experience | 0.720 | *** | 0.696 | *** | −0.273 |

| Winescape | <--- | Wine Experience | 0.696 | *** | 0.655 | *** | −0.501 |

| Wine Tasting Excitement | <--- | Wine Experience | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - | - |

| Wine Storytelling 5 | <--- | Wine Storytelling | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - | - |

| Wine Storytelling 4 | <--- | Wine Storytelling | 1.137 | *** | 0.949 | 0.000 | −1.942 * |

| Wine Storytelling 3 | <--- | Wine Storytelling | 1.092 | *** | 0.977 | 0.000 | −1.149 |

| Wine Storytelling 2 | <--- | Wine Storytelling | 1.314 | *** | 1.050 | 0.000 | −2.273 ** |

| Wine Storytelling 1 | <--- | Wine Storytelling | 1.327 | *** | 1.011 | 0.000 | −3.027 *** |

| Wine Tasting Excitement 3 | <--- | Wine Tasting Excitement | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||

| Wine Tasting Excitement 2 | <--- | Wine Tasting Excitement | 1.124 | *** | 1.011 | 0.000 | −1.349 |

| Wine Tasting Excitement 1 | <--- | Wine Tasting Excitement | 0.807 | *** | 0.718 | 0.000 | −1.261 |

| Wine Involvement 5 | <--- | Wine Involvement | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - | - |

| Wine Involvement 4 | <--- | Wine Involvement | 0.991 | *** | 0.953 | 0.000 | −0.423 |

| Wine Involvement 2 | <--- | Wine Involvement | 1.031 | *** | 1.091 | 0.000 | 0.589 |

| Wine Involvement 2 | <--- | Wine Involvement | 0.885 | *** | 1.045 | 0.000 | 1.652 * |

| Wine Involvement 1 | <--- | Wine Involvement | 1.240 | *** | 1.086 | 0.000 | −1.326 |

| Winescape 1 | <--- | Winescape | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | - | - |

| Winescape 2 | <--- | Winescape | 1.058 | *** | 0.668 | 0.000 | −3.895 *** |

| Winescape 3 | <--- | Winescape | 1.074 | *** | 0.693 | 0.000 | −3.587 *** |

| Winescape 4 | <--- | Winescape | 0.944 | *** | 0.850 | 0.000 | −0.906 |

| Wine Tasting Excitement 4 | <--- | Wine Tasting Excitement | 1.076 | *** | 1.040 | 0.000 | −0.400 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, V.; Ramos, P.; Almeida, N.; Santos-Pavón, E. Developing a Wine Experience Scale: A New Strategy to Measure Holistic Behaviour of Wine Tourists. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198055

Santos V, Ramos P, Almeida N, Santos-Pavón E. Developing a Wine Experience Scale: A New Strategy to Measure Holistic Behaviour of Wine Tourists. Sustainability. 2020; 12(19):8055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198055

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Vasco, Paulo Ramos, Nuno Almeida, and Enrique Santos-Pavón. 2020. "Developing a Wine Experience Scale: A New Strategy to Measure Holistic Behaviour of Wine Tourists" Sustainability 12, no. 19: 8055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198055

APA StyleSantos, V., Ramos, P., Almeida, N., & Santos-Pavón, E. (2020). Developing a Wine Experience Scale: A New Strategy to Measure Holistic Behaviour of Wine Tourists. Sustainability, 12(19), 8055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198055