Payment for Environment Services to Promote Compliance with Brazil’s Forest Code: The Case of “Produtores de Água e Floresta”

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

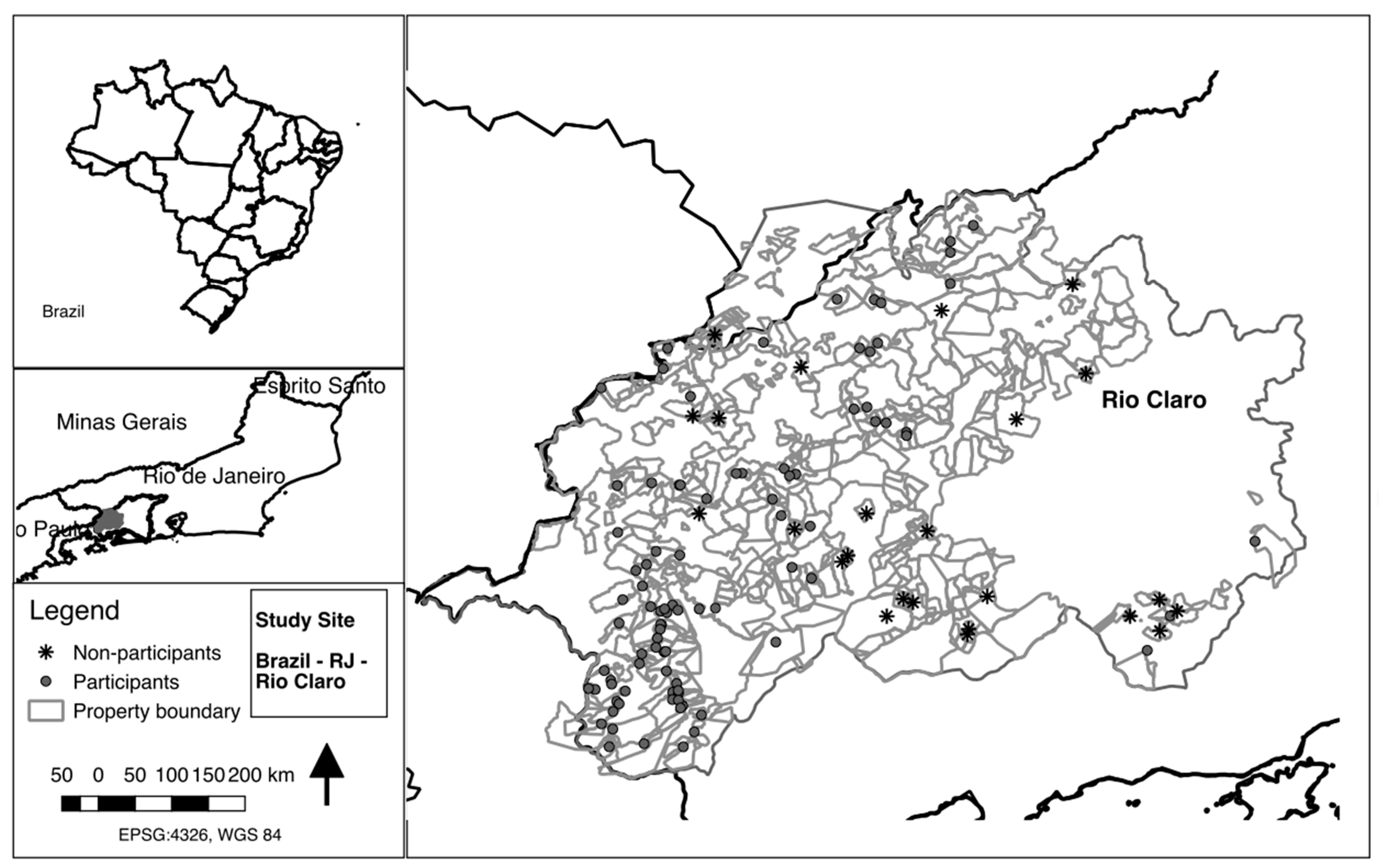

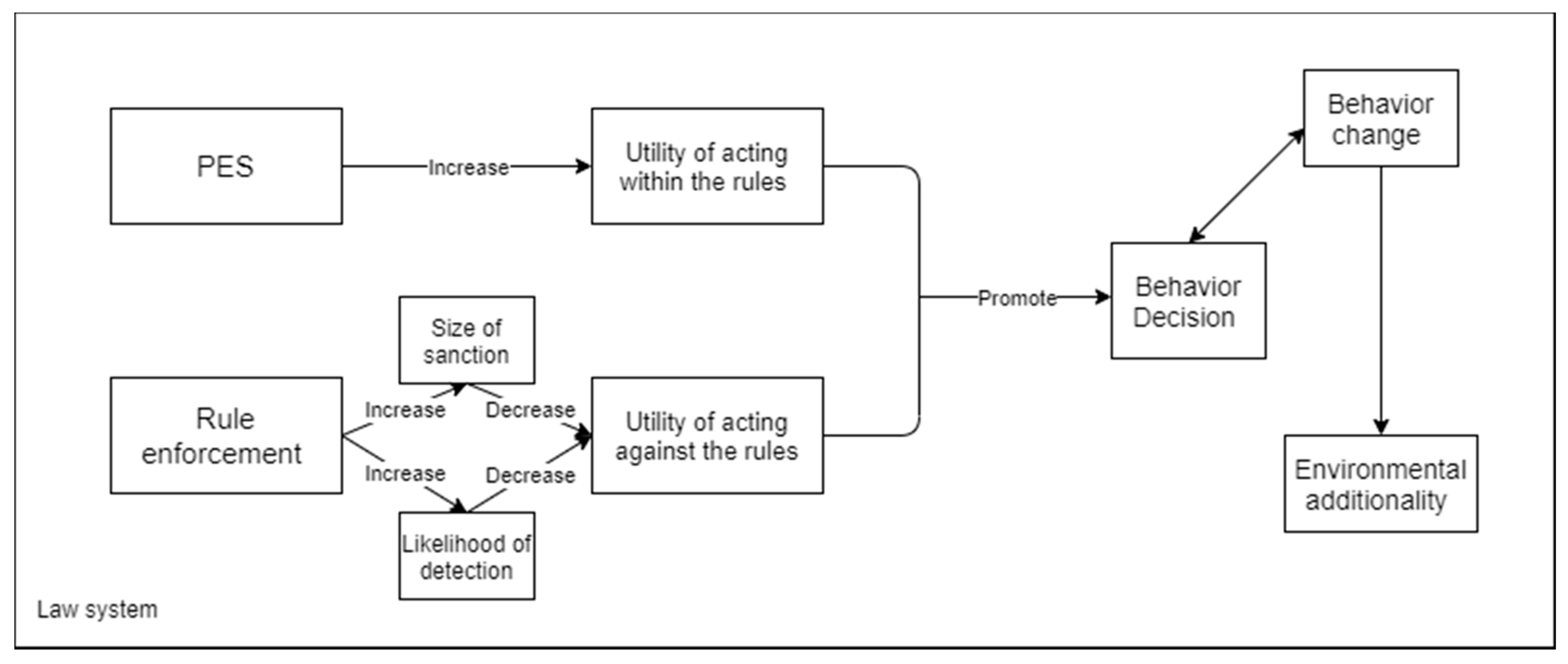

2.1. Study Area

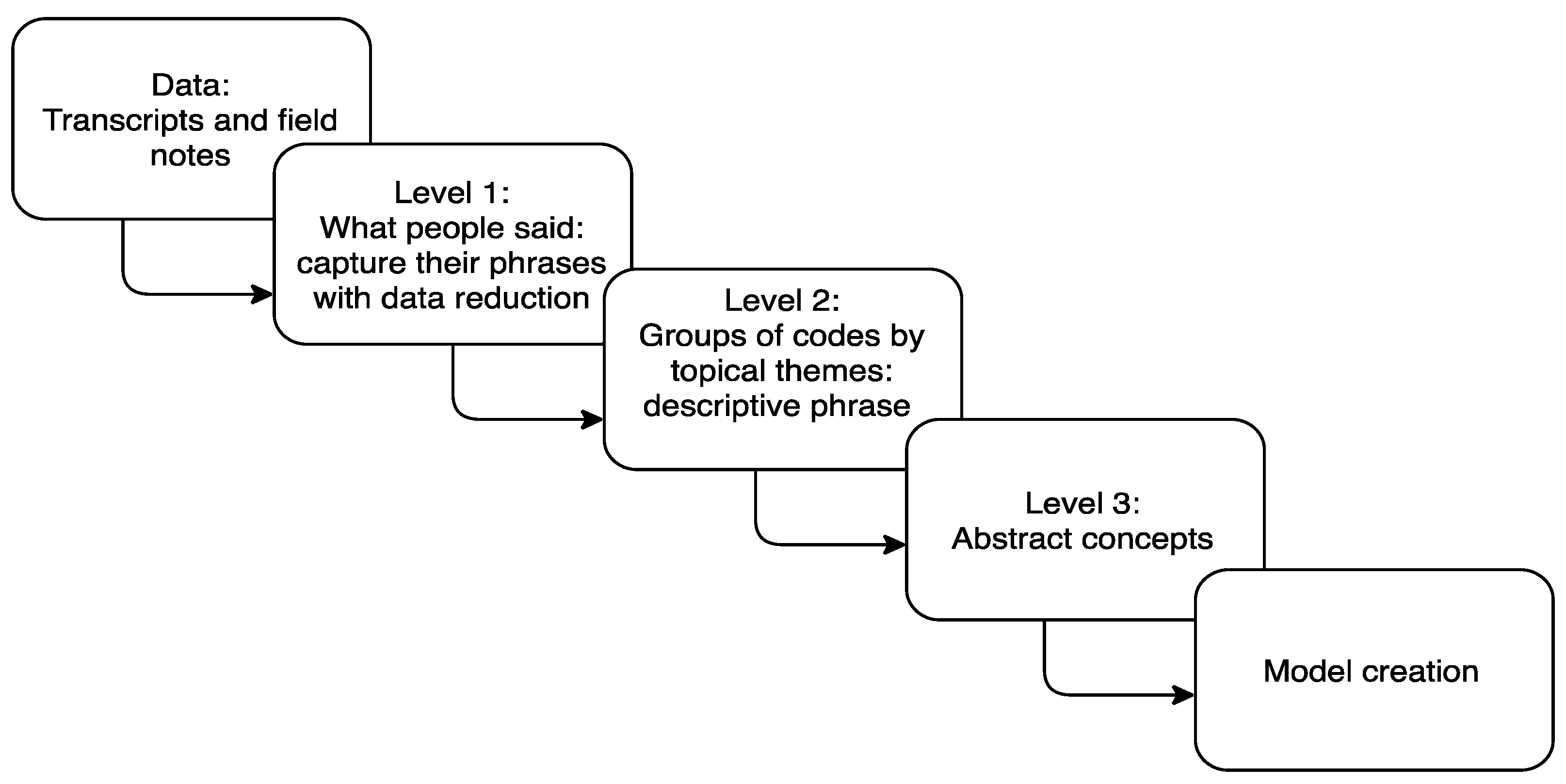

2.2. Methodology

3. Results

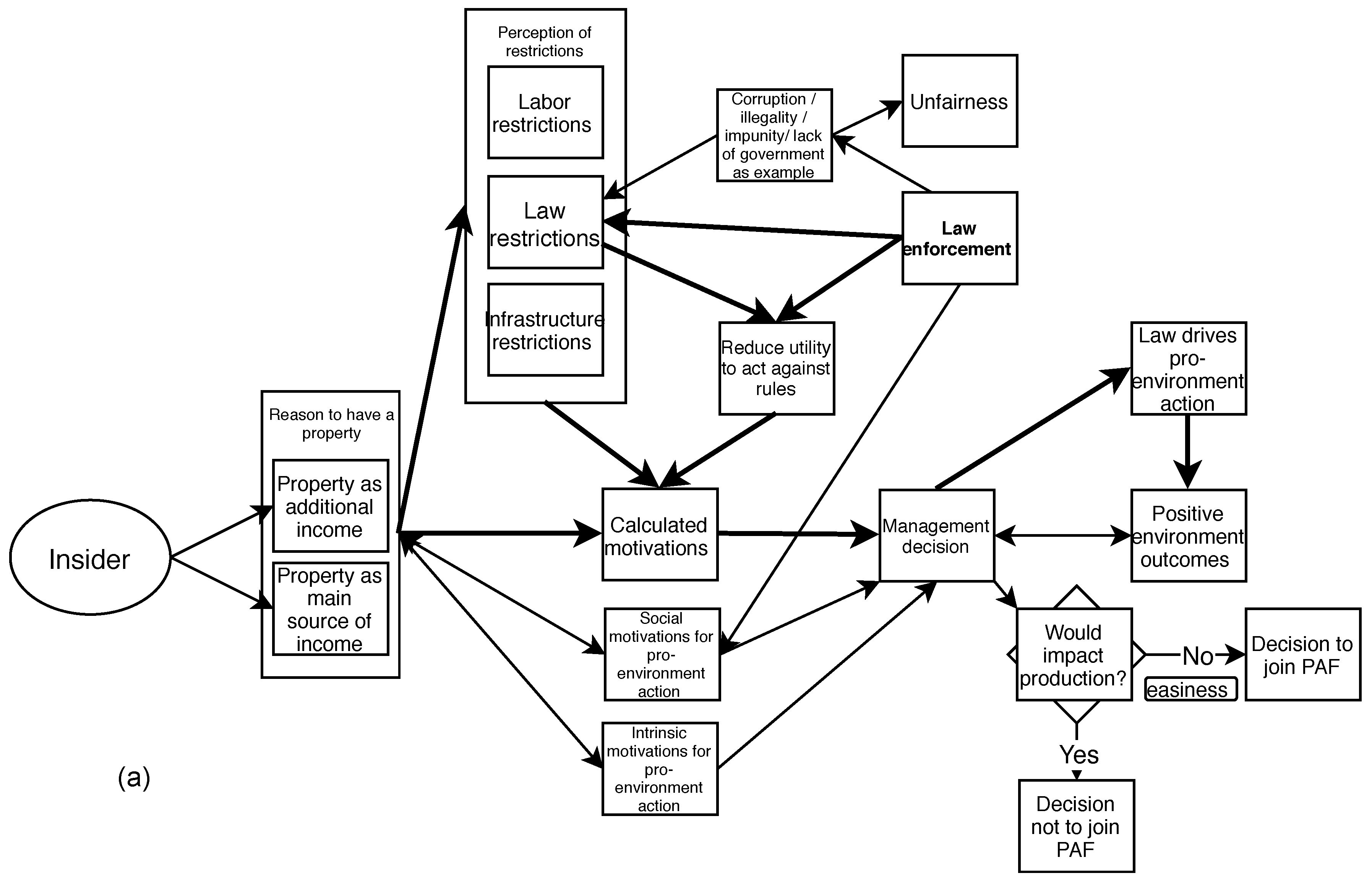

3.1. Motivations

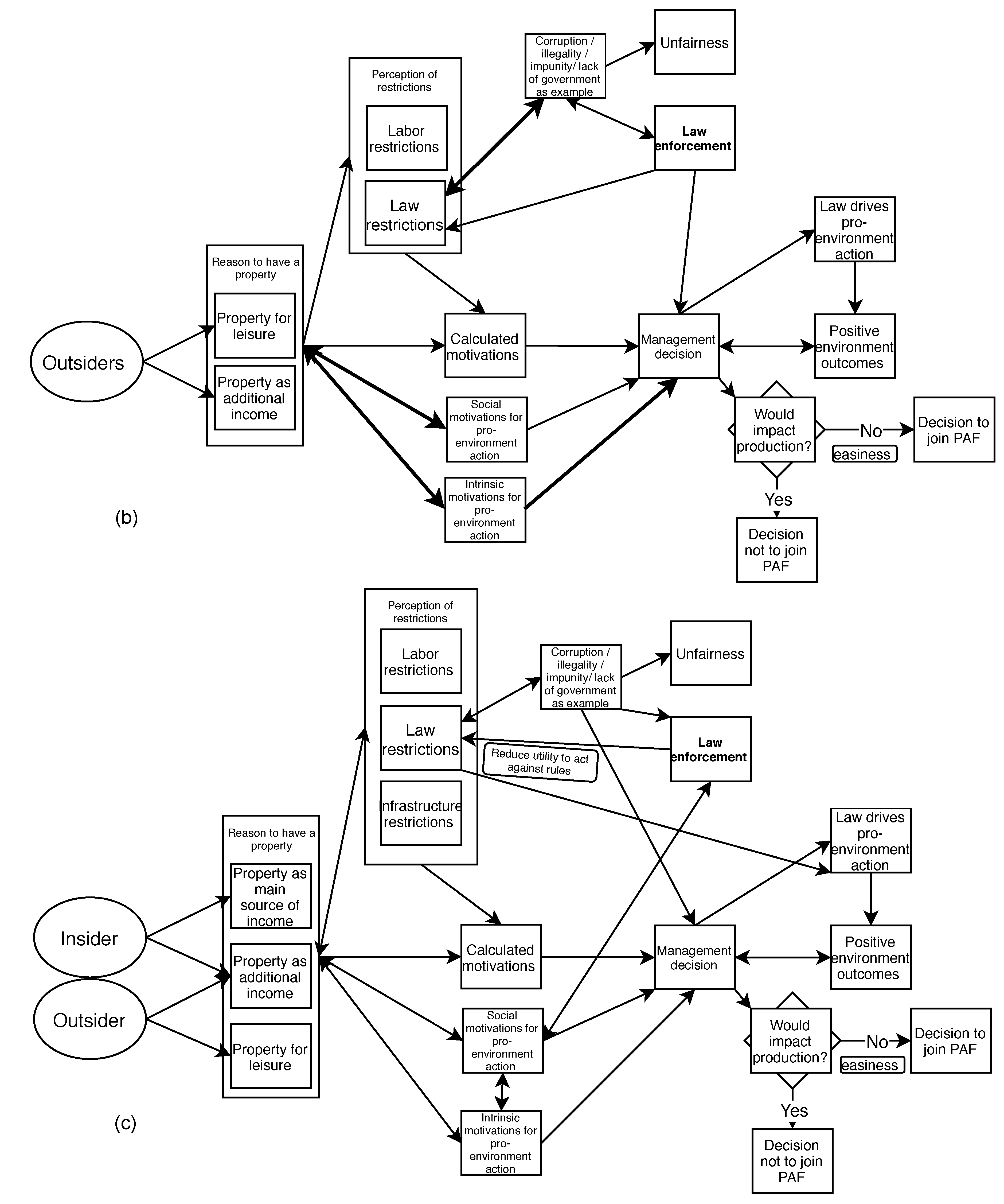

3.2. Relationships between Themes

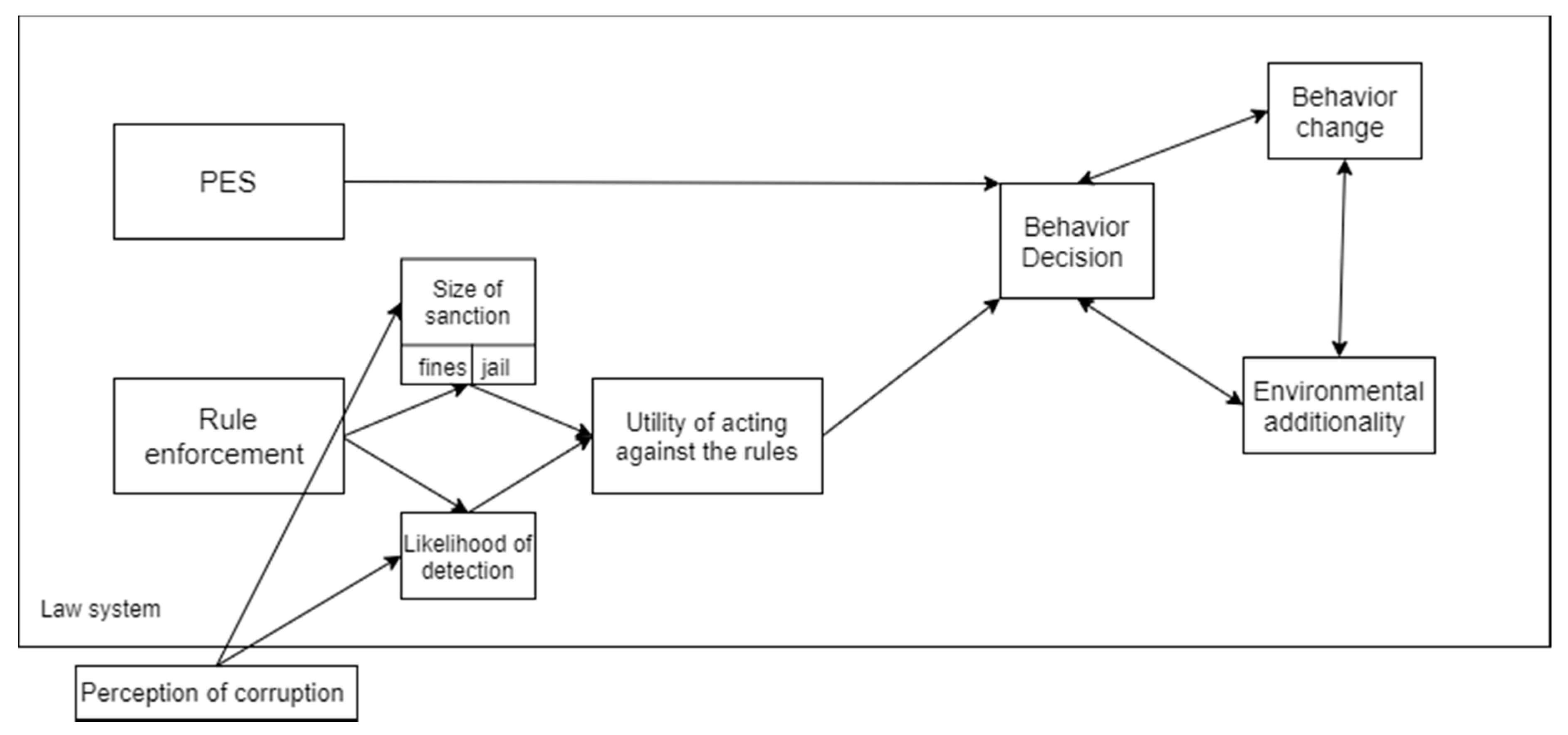

4. Discussion

4.1. Contributions to the PES Literature

4.2. Insights from ELR

4.3. Implications Emerging from the Empirical Findings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Detailed Coding Procedure

| Objective | Open-Response Questions |

|---|---|

| 1. General information about property(ies) management |

|

| 2. Landowners’ perception about forests, ecosystems services and reasons for the distribution of forest and regrowth areas on their land |

|

| 3. Landowners’ motivations for joining or not PAF |

|

| 4. Landowners’ perception and knowledge about environmental legislation |

|

| Topic | First-Level Code | Idea It Refers | Codes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Reasons for having the land | Property for leisure | Uses the property for leisure activities | PAF82, PAF71, PAF33, PAF18, PAF45, PAF12, PAF77, PAF21, PAF17, PAF61, PAF22, PAF23 |

| Property to share with friends | Wanted the property to have a place to enjoy with friends | PAF51 | |

| Desire to pursue a rural lifestyle | Identifies with rural life | PAF82, PAF23, PAF05 | |

| Property as investment | Property is a way of creating savings to meet future necessities in a period of instability in the country | PAF82, PAF68, PAF56, PAF17, PAF25, PAF68, PAF42, PAF81 | |

| Family had the property for leisure | Family had this property before the current owner and used it for leisure | PAF40, PAF56, PAF50, PAF42, PAF45, PAF08, PAF29, PAF32, PAF79, PAF70 | |

| Family livelihood related to property | Property accounts for a big part of family’s income | PAF71, PAF33, PAF50, PAF11, PAF16, PAF47, PAF59, PAF72, PAF78 | |

| Property for cattle ranching, | Has the property to raise cattle | PAF78, PAF86, PAF01 | |

| Family already managed the property | Plans to keep the activity the family had before | PAF78, PAF86, PAF66, PAF10, PAF04, PAF72 | |

| Looking for escape from the city | Wanted to have an alternative to the busy city lifestyle | PAF86, PAF36, PAF89, PAF37, PAF28, PAF18, PAF88, PAF12, PAF68, PAF36, PAF44, PAF61 | |

| Family likes the region and property | Family demonstrates affection for the place | PAF56, PAF54, PAF19, PAF05, PAF12 | |

| Property as inheritance | Leave something for the family | PAF88, PAF12, PAF68, PAF36, PAF63 | |

| Property as additional income source in hard times | Can sell cattle when the family needs money | PAF56 | |

| Family dream | Family member always wanted a property | PAF37, PAF54 | |

| Retirement plan | Bought it thinking about using it when retired | PAF17, PAF81, | |

| Raise horses | Desired to have an income from horses | PAF73 | |

| Housing | Family uses mainly for residency | PAF32, PAF31, PAF14, PAF34 | |

| Inspiration | Bought to have inspiration and creativity to write | PAF67 | |

| Forest conservation | Bought already thinking about forest conservation | PAF64, PAF51 | |

| 2. Aims for the land | Property for forest conservation | Wants to maintain the property for forest conservation | PAF40, PAF88, PAF66, PAF64, PAF51, PAF54, PAF31, PAF67 |

| Property in a park area | Acknowledges the limit use of the property because it is within a protected area | PAF78 | |

| Property for family livelihood | Aims to provide for the family with property | PAF78, PAF16, PAF72, PAF78 | |

| Aims to improve the property | Wants to get more profitability from the property | PAF78, PAF86 | |

| Labor restriction changed the aim of the property | Had to change the aim due high labor cost | PAF68, PAF36, PAF55, PAF01, PAF58, PAF21 | |

| Cattle | Desire to have cattle related activities | PAF56, PAF42, PAF54, PAF57 | |

| Use for leisure | Use the property for leisure | PAF33, PAF77, PAF21, PAF45, PAF12, PAF04, PAF08, PAF74, PAF70, PAF61 | |

| Use for leisure because cannot change it | The law does not allow to change the land cover, so uses for leisure | PAF58 | |

| Aging | Getting older and reducing the work load | PAF37, PAF58, PAF11 | |

| Difficulty in access | Moved from other property to be closer to the city/school | PAF03 | |

| Additional income | Aims to use the property to contribute in the income | PAF18, PAF45, PAF10, PAF73, PAF63, PAF14, PAF05, PAF81 | |

| “Rents” for maintenance | Let people use the property in exchange for work in maintenance of the property | PAF21, PAF08 | |

| Tourism | Aims to implement a tourism related business | PAF06, PAF54, PAF25, PAF61, PAF05, PAF57 | |

| Corruption prevented to implement economic activity | To implement the desire activity would have to “buy” license | PAF42 | |

| Tried activities that did not work | Gave up of activity in consequence of perceived failure in generating income | PAF42, PAF73, PAF81, PAF23 | |

| Bar in the property | Has a bar to complement income | PAF34 | |

| 3. Reason for maintaining forest | Maintain forest because it is not allowed to cut | Clearing forest is not allowed | PAF82 |

| Maintain forest because of water | Believes forest is important for water resources | PAF82, PAF56, PAF89, PAF33, PAF50, PAF03, PAF17, PAF10, PAF54, PAF23, PAF57, PAF81, PAF72 | |

| Maintain forest because of animals | Maintain forest for the sake of animals | PAF82, PAF37, PAF50, PAF51, PAF10, PAF04, PAF08, PAF22, PAF81, PAF72 | |

| Maintain forest because of future generations | Maintain forest for the sake of future generations | PAF82, PAF89, PAF66, PAF51, PAF31, PAF34, PAF67 | |

| Environmental awareness | Maintain the forest because s/he considers her/himself to be an environmentally conscious person | PAF71, PAF68, PAF36, PAF50, PAF18, PAF17, PAF12, PAF51, PAF10, PAF57, PAF31, PAF63, PAF81 | |

| Enjoys the forest | Maintain forest because s/he likes the forest | PAF68, PAF36, PAF40, PAF56, PAF33, PAF50, PAF18, PAF42, PAF10, PAF22 | |

| Obligation as a citizen | Protecting forest is a moral requirement, wanted to be an example for society | PAF40, PAF51, PAF54, PAF57, PAF31 | |

| Wood source | Uses wood extracted from the forest | PAF86, PAF89, PAF03, PAF17, PAF72 | |

| Law required | The law requires forest maintenance | PAF78, PAF86, PAF12, PAF25 | |

| Too small almost does not have forest | PAF28 | ||

| Religion | God thinks it is important to conserve, nature is God | PAF68, PAF18 | |

| Labor expenses | It is too expensive to pay labor to deforest | PAF10 | |

| Family teaching | The family already conserved the forest and wants to pass on this lesson | PAF31 | |

| 4. Reasons to restore forest | Trees are beautiful | Planted Ipes (Handroanthus) because believes they are beautiful or other trees | PAF82, PAF57 |

| Recover a degraded area | Wants to reforest to recover a degraded area | PAF71, PAF56, PAF66, PAF10, PAF63 | |

| Areas around spring | Reforestation is allowed because was around springs, or recover a spring | PAF78, PAF56, PAF89, PAF33, PAF18, PAF63 | |

| Land abandonment and areas that were not being used | Was not using some areas and the forest grew back | PAF86, PAF12 | |

| Changed production for tourism | The forest grew back when changed focus of the property | PAF86, PAF36 | |

| Trees in the fence line with neighbors | Planted trees in the fence line with neighboring property for more privacy and/or not moving the fence | PAF89 | |

| Off-site mitigation | Received money from a company to perform an off-site mitigation to compensate and environment damage | PAF50, PAF54 | |

| Reduce the problem with fire | Believed that the forest existence could reduce the problem and fear of having fires too close | PAF25 | |

| Shade for cattle | Allowed tree regrowth in some spots to provide shade for the cattle | PAF72 | |

| 5. Perceived benefits of forest | Believes forest in important for water | Relates forest to water availability and provision and to high humidity | PAF82, PAF56, PAF37, PAF33, PAF50, PAF03, PAF28, PAF18, PAF88, PAF77, PAF21, PAF17, PAF06, PAF42, PAF45, PAF66, PAF12, PAF10, PAF04, PAF08, PAF25, PAF22, PAF57, PAF31, PAF19, PAF63, PAF67, PAF81, PAF72 |

| Reforestation does not increase water availability | People normally think reforestation increases water availability, but reforestation does not increase water availability | PAF64 | |

| Erosion control | Forest reduces the impact of rain on the soil | PAF28, PAF42, PAF45, PAF64, PAF04 | |

| Believes forest in important for conservation | Believes forest conservation and biodiversity are benefits | PAF82, PAF50, PAF40, PAF03, PAF18, PAF88, PAF42, PAF51, PAF08, PAF25, PAF22, PAF14, PAF31, PAF63, PAF81 | |

| Clear Air | The air is cleaner, “purer,” near forest | PAF86, PAF50, PAF17, PAF45, PAF12, PAF55, PAF25, PAF22, PAF14, PAF31, PAF63, PAF34, PAF81, PAF72 | |

| Breeze | Temperature and breezes are nicer near forest | PAF86, PAF37, PAF42, PAF45 | |

| Peace and beauty, stress relief | The forest provides a feeling of peace and encourages contemplation | PAF50, PAF12, PAF42, PAF51, PAF08, PAF57, PAF31, PAF19, PAF67, PAF81, PAF72 | |

| Society collaboration | Feels that s/he is collaborating in the society | PAF17, PAF51, PAF23, PAF67 | |

| Climate more stable near forest | The forest reduces variations in temperature and humidity | PAF77, PAF17, PAF21, PAF45, PAF66, PAF51, PAF55, PAF10, PAF04, PAF25, PAF34 | |

| Tourism | The forest brings tourism to the region | PAF45 | |

| Firewood | The forest provides firewood | PAF10, PAF22, PAF57 | |

| Payment | The PAF payment is a benefit from forest | PAF08 | |

| Work inspiration | The forest inspires composing music | PAF67 | |

| Better soil close to the forest | PAF72, PAF40 | ||

| 6. Perceived drawbacks from forest | Nothing for heirs | Not drawback, but if they only left the forest to grow back, the heirs would have less land value | PAF64 |

| Not at all | Interviewee demonstrated a strong denial of drawbacks of forest presence | PAF82, PAF56, PAF21, PAF12, PAF51 | |

| No drawbacks, but fencing incurs costs | Interviewee specifically mentioned no drawbacks but | PAF40 | |

| Lost is land for production | The forest occupies an area that could be used for production | PAF78, PAF86 | |

| Problems with hunters or palm extractors | The forest attracts people to hunt and extract palm | PAF36, PAF86, PAF56, PAF42, PAF45, PAF10, PAF54, PAF01, PAF31, PAF19, PAF67, PAF81 | |

| Conflict with neighbors | Neighbor allows cattle to cross into others’ property, which generated conflicts | PAF23 | |

| Too many restrictions on use of forest land | The law places too many restrictions on forest land use, reduces the options for landowners | PAF23 | |

| The landowner incurs more responsibilities with forested land than with pasture | If the pasture burns, nobody says anything, but if the forest burns the landowner is fined | PAF40 | |

| Humidity | Does not want forest near the house because it makes it too humid | PAF25 | |

| 7. Land management resulting in land use changes | Deforested in the past for cattle | Deforested to increase area for cattle | PAF78, PAF86, PAF89, PAF72 |

| Let forest regrow | Forest grew back after abandonment of production | PAF68, PAF36, PAF37, PAF18, PAF66, PAF45, PAF12, PAF64 | |

| Was pasture when arrived | Reported that when arrived in the property everything was pasture and now there is a lot of forest | PAF50, PAF51, PAF67 | |

| Transformed property in condominium | Divided and included many houses | PAF25, PAF55 | |

| 8. Learned about PAF | Neighbors participating | Found out about the project because neighbors were participating | PAF82, PAF71, PAF56, PAF03, PAF77, PAF57, PAF67 |

| Surprised to be accepted in PAF | Has a lot of forest, so did not understand why they would be accepted in a PES project | PAF71 | |

| Part of COMDEMA | Member of the municipality environment committee | PAF40, PAF50 | |

| TV | Saw information about the program on television | PAF78 | |

| Local institution | EMATER Rio Claro (Rio Claro’s technical assistance and rural extension company), rural labor organizations and/or environment secretariat provided information | PAF86 | |

| Created the project | Was part of the group that created the project | PAF68, PAF50 | |

| Project went until property | The project staff visited the property to provide information | PAF89, PAF03, PAF21, PAF45, PAF51, PAF10, PAF04, PAF01, PAF73, PAF08, PAF22, PAF34 | |

| Friend or family | A friend of the family informed him/her about the project | PAF66, PAF12, PAF31, PAF63, PAF81 | |

| Looked for help to restore to fulfil environment regulation | Was informed about PAF while looking for ways to fulfil an environment requirement for building a condominium | PAF55 | |

| 9. Motivation to participate | Everybody around was participating, so joined too | Joined the project because the neighbors were also participating | PAF82, PAF56, PAF89 |

| To protect springs | Joined the project to protect or increase protection for springs | PAF82, PAF56, PAF03, PAF21, PAF06, PAF66, PAF12, PAF57, PAF81 | |

| For help with fencing | Joined the project for the help with fencing | PAF82, PAF56, PAF37, PAF21, PAF51, PAF73 | |

| Would have joined without the money | Would have joined without the money | PAF82, PAF56, PAF89, PAF03, PAF77, PAF21, PAF51, PAF73, PAF57 | |

| Already was doing what was needed and would get money for it | Joined the project because already had forest and would get money by joining | PAF82, PAF33, PAF50, PAF67 | |

| No reason not to join | Did not see any reason not to join; was already doing required practices | PAF50, PAF45, PAF51, PAF57 | |

| Sponsorship of increase in protection | The program provides sponsorship to increase the protected area on the property | PAF40, PAF77, PAF21 | |

| Money | Joined because of payment | PAF78, PAF89, PAF33, PAF10, PAF23, PAF19, PAF67 | |

| No negative impact | Joined because the areas that would go into reforestation would not reduce agricultural production | PAF78, PAF21, PAF06 | |

| Desire to restore areas | Desire to protect areas around river because believes the rivers in the world are drying out; protect areas experiencing erosion | PAF86, PAF42, PAF66, PAF25, PAF63, PAF34, PAF81 | |

| Money attracts corruption | Almost did not join because money attracts corruption | PAF56 | |

| Project people were nice | Joined because the people that were recruiting for the project were very nice; wanted to help the project staff | PAF56, PAF89, PAF14 | |

| Avoid criminal fires and hunt | Joined because other people get to know you are in the program and then do not start fires or hunt on your property | PAF89 | |

| Avoid land invasion | Joined because of concern about land invasion and believed the project’s presence would avoid it | PAF89 | |

| Increase local environment awareness | Joined because wanted to help to increase local environment awareness | PAF33, PAF21, PAF31 | |

| Believes in the PES logic | Believes that the forest is providing a service to society and that landowners should therefore be compensated and that payment is a good incentive for those that depend on the land | PAF50, PAF21, PAF22 | |

| The project sounded important | Project staff explained what the project entailed and it sounded important for the environment | PAF03, PAF45, PAF08, PAF72 | |

| Likes forest | Decided to participate because always liked forest | PAF18, PAF77, PAF21, PAF66, PAF08 | |

| Wanted to restore and could not do it alone | Joined because wanted to restore part of the property and could not do it alone | PAF88, PAF45, PAF66, PAF73, PAF81 | |

| Used the term rent for PAF | Mentioned that s/he “rented” a small area for PAF | PAF28, PAF45, PAF32 | |

| Legislation | Thought about the legislation because would have to do it eventually anyway | PAF45, PAF22 | |

| Contract flexibility | The contract is renewed every two years, allows maintenance of rights | PAF51, PAF73 | |

| Reduce cost of required reforestation | The legislation requires a forest reserve in order to allow property to be divided into a condominium | PAF55 | |

| Help to avoid tax fine | Had a tax fine because the auditor did not believe the amount of production declared in relation to the size of land | PAF54 | |

| Be able to produce something in the forest area | Aimed to use the forest area, to get benefit from it. | PAF23 | |

| Wanted to restore and could not do it alone | Joined because wanted to restore part of the property and could not do it alone | PAF88, PAF45, PAF66, PAF73, PAF81 | |

| Used the term rent for PAF | Mentioned that s/he “rented” a small area for PAF | PAF28, PAF45, PAF32 | |

| Legislation | Thought about the legislation because would have to do it eventually anyway | PAF45, PAF22 | |

| Contract flexibility | The contract is renewed every two years, allows maintenance of rights | PAF51, PAF73 | |

| Reduce cost of required reforestation | The legislation requires a forest reserve in order to allow property to be divided into a condominium | PAF55 | |

| Help to avoid tax fine | Had a tax fine because the auditor did not believe the amount of production declared in relation to the size of land | PAF54 | |

| Produce something in the forest area | Aimed to use the forest area, to get benefit from it. | PAF23 | |

| Guilt for past deforestation | Realized that past deforestation activities could negatively affect downstream water users | PAF01 | |

| Recognition | Recognition by society that they were doing an important thing by preserving their forest | PAF19, PAF40 | |

| Perception of outcome | Saw the forest growing in some properties with the project | PAF67 | |

| Benefit for others | Joined because would be helping to provide water for the city | PAF72 | |

| 10. Behavior changes required | No behavior change | Reported not have changed any behavior due to the project nor received any environmental benefit because of the project | PAF82, PAF40, PAF78, PAF86, PAF56, PAF33, PAF03, PAF21, PAF06, PAF12, PAF64, PAF51, PAF55, PAF04, PAF22, PAF57, PAF31, PAF19, PAF63, PAF34, PAF67 |

| Nothing was done in the property | Reported that the project had not yet completed do the reforestation activities | PAF71, PAF78, PAF86, PAF89, PAF73, PAF67, PAF81 | |

| Became aware of the importance of forest and stopped deforesting | The project increased environment awareness and led stopping deforestation | PAF89 | |

| The change in the property did not impact production | The project protects reforested land and therefore did not have an impact on the productivity of the property | PAF42, PAF66, PAF10, PAF08 | |

| Stopped people from taking wood from the forest | The project would prevent taking wood from the forest | PAF14 | |

| 11. Perception of outcomes | Increase in water availability | Sees an increase in water availability | PAF21, PAF42 |

| Erosion reduced | Perceive erosion reduction affecting the river | PAF45, PAF04 | |

| Needed more audits | The project should have more audits by the state environmental institutions to guarantee that the reforestation was done properly. | PAF54 | |

| Needed more rigor in program execution | Program execution required more generate more results in the reforested areas. | PAF54 | |

| Reduced the problem with fire | The reforestation helped control fires originating on neighbors’ land | PAF14 | |

| Worked in the project | Someone in the landowner family worked on the project | PAF34, PAF14 | |

| 12. Knowledge of environmental regulations | Never worried too much because believes conservation is important | Did not try to find information about environment regulations because they do not want take actions that hurt the environment | PAF82, PAF64 |

| Is aware of PPA and RL | Mentioned the PPA and the RL requirements | PAF82, PAF71, PAF78, PAF89, PAF03, PAF88, PAF06, PAF45, PAF64, PAF01, PAF73, PAF08, PAF25, PAF22, PAF57, PAF63, PAF67 | |

| Increase in environment awareness in the country | Perceives an increase in environmental awareness in the country | PAF71, PAF40, PAF78, PAF36, PAF68, PAF73 | |

| Not allowed to touch anything | The law does not allow changing, extracting, or, removing trees on forest land | PAF78, PAF10, PAF23 | |

| Does not know anything | Claims not to know anything about environmental regulation | PAF86 | |

| Deforestation is not allowed | Deforestation is not allowed | PAF86, PAF89, PAF33, PAF37, PAF21, PAF12, PAF73, PAF08, PAF57, PAF14, PAF34, PAF67 | |

| Fire is not allowed | Using fire for land management is not allowed | PAF33, PAF37, PAF21, PAF22, PAF57, PAF14, PAF34 | |

| Bad chemicals not allowed | Toxic agricultural chemicals cannot be applied near th rivers | PAF06, PAF42, PAF45, PAF14 | |

| Aware of rules | Mentioned many rules including Forest Code requirements | PAF40, PAF56, PAF68, PAF71, PAF50, PAF66, PAF51, PAF55, PAF54, PAF14, PAF31 | |

| Not allowed to extract river sand | The law does not allow to removal of sand from rivers | PAF37 | |

| Not allowed to extract river sand | The law does not allow to removal of sand from rivers | PAF37 | |

| 13. Opinion about environmental regulations | Conservation is important | Thinks the regulations are important because conservation is important | PAF82, PAF40, PAF86, PAF68, PAF36, PAF56, PAF89, PAF33, PAF37, PAF50, PAF03, PAF17, PAF45, PAF66, PAF12, PAF64, PAF51, PAF10, PAF04, PAF54, PAF73, PAF32, PAF22, PAF31, PAF63, PAF34, PAF67, PAF81, PAF72 |

| Some regulations are overdue | Believes there is an excess in some environment regulations, that some go beyond what is necessary | PAF71, PAF40, PAF37, PAF18, PAF42, PAF73, PAF25, PAF19 | |

| Corruption creates difference in actions between big and small landowners | The law is applied differently to rich and poor landowners | PAF71, PAF86, PAF33, PAF21, PAF45, PAF54, PAF23, PAF14, PAF67, PAF72 | |

| Law is not considered for decision-making | The landowners do not consider the law for decision making | PAF71, PAF56, PAF89, PAF33, PAF37, PAF12, PAF51, PAF55, PAF04, PAF34 | |

| In favor of the landowners’ responsibilities | Believes the landowner as a citizen should be responsible for forest on their land | PAF40, PAF88, PAF66 | |

| Any law must be respected | If it is a law, it should be respected | PAF78, PAF03 | |

| People would deforest if it did not exist | If the law did not exist people would cut everything down to plant pasture | PAF78, PAF86, PAF03, PAF18, PAF17, PAF06, PAF45, PAF10, PAF08, PAF25, PAF32, PAF14, PAF63, PAF67, PAF81, PAF72 | |

| Was informed about PPA requirements by the project | When the project was trying to enroll people, the staff informed them that what they were proposing was required in the law | PAF04 | |

| Prevents profiting from the property | The environment regulation restricts the producer too much, it makes the forest of little use | PAF23 | |

| The government itself does not do anything | The government creates all the laws but does not do anything to improve environment awareness | PAF57 | |

| Overlap of legislation | There are so many overlapping environment regulations that it is hard to keep track | PAF19 | |

| 14. Perceived enforcement of environmental regulations | The places with bad roads do not get any enforcement | The places with bad roads do not get any enforcement | PAF56, PAF03, PAF18, PAF67 |

| Never saw law enforcement | Reported that never saw or heard about law enforcement actions | PAF82, PAF03, PAF66, PAF12, PAF23, PAF73, PAF08, PAF63, PAF81 | |

| Rigor in enforcement in relation to deforestation | Reported that the legislation enforcement has been strict or knows people who were fined | PAF71, PAF40, PAF86, PAF36, PAF68, PAF37, PAF50, PAF21, PAF10, PAF04, PAF01, PAF32 | |

| Fine is too high | If environmental enforcement includes fines, the fines are too high | PAF01 | |

| Rigor in the enforcement in relation to hunting | Reported that the legislated enforcement has been strict | PAF40 | |

| Corruption of the enforcement agent | Reported that the enforcement agent may be corrupt | PAF40, PAF68, PAF36, PAF42, PAF45, PAF22, PAF19 | |

| Fine is not paid | The landowners that get fined do not pay the fines | PAF68, PAF36, PAF14 | |

| Was previously fined | Mentioned incurring an environment fine | PAF78, PAF19 | |

| Park area | Property is within the protected area and therefore sees more enforcement | PAF78, PAF21 | |

| Some rigor in environment regulation enforcement | Does not seem to perceive strong rigor, but saw environmental agents or knows people that were fined | PAF89, PAF33, PAF06, PAF42, PAF45, PAF64, PAF54, PAF22, PAF57, PAF34, PAF67, PAF72 | |

| The enforcement agents do not know how to communicate with the landowner | The enforcement agents do not know how to communicate with the landowner, they arrive in the property without explaining the reasoning behind the legislation and give people fines | PAF37, PAF19, PAF67 | |

| Changed behavior because of increased perception of enforcement | Used to deforest, but learned that it was illegal and liable to sanctions | PAF01 | |

| Overlap of enforcement in different levels of government | The overlap of environment regulations in different levels of government leads to excess bureaucracy and confusion | PAF19 | |

| Overlap of enforcement in different levels of government | The overlap of environment regulations in different levels of government leads to excess bureaucracy and confusion | PAF19 | |

| 15. Perceived motivations to comply (or not) with environment legislation | Normative motivations—agrees with the law or believes it is the right thing to do | Complies with environment law because s/he believes it is the right thing to do | PAF82, PAF40, PAF56, PAF17, PAF66, PAF12, PAF55, PAF10, PAF54, PAF23, PAF73, PAF22, PAF14, PAF19, PAF63, PAF34, PAF81 |

| Lack of knowledge about environmental legislation | Believes people do not have knowledge about the legislation | PAF71, PAF77 | |

| Calculated motivations | Believes that the financial utility (money and enforcement) is the most important reason for people to comply or not with environmental regulations | PAF71, PAF78, PAF68, PAF56, PAF89, PAF50, PAF03, PAF18, PAF77, PAF06, PAF45, PAF66, PAF51, PAF55, PAF10, PAF54, PAF01, PAF73, PAF08, PAF22, PAF57, PAF31, PAF19, PAF34, PAF72 | |

| People believe that there will not be sanctions | People are aware of the law, but do not think they will be sanctioned | PAF78, PAF68, PAF56, PAF89, PAF33, PAF50, PAF88, PAF77, PAF25, PAF45, PAF51, PAF10, PAF54, PAF23, PAF08, PAF14, PAF31, PAF34, PAF81 | |

| Cost of bureaucracy | The biggest cost associated with the law if you do not follow regulations is to have to deal with the bureaucracy | PAF68, PAF36, PAF03, PAF18 | |

| Sanctions are not complete and corrupts the citizenry | People do not worry about sanctions because they serve as a way of instituting corruption and bribery | PAF50, PAF77, PAF42, PAF45, PAF51, PAF55, PAF54, PAF23, PAF22, PAF67 | |

| It is necessary to understand the reasoning | People are convinced to conserve forest if they understand the importance of it. | PAF50, PAF77, PAF06, PAF64, PAF31, PAF81 | |

| People live today and do not worry about tomorrow | People make decisions thinking about what they need today, people live today and do not worry about tomorrow, they do not think about the long term | PAF64 | |

| 16. CAR perceived change in environmental regulation and enforcement | Pays someone to deal with bureaucracy | Does not know about CAR, because pays someone to deal with bureaucracy | PAF64 |

| Has not done it | Did not remember to do it or lives in urban area | PAF82, PAF71, PAF28, PAF25, PAF34 | |

| Depends on political will | CAR seems to be a good instrument but its application will depend on the will of politicians; corruption is instituted | PAF40, PAF66, PAF54, PAF23, PAF73, PAF22 | |

| Nothing will change | CAR will not change anything in terms of land management or enforcement | PAF78, PAF86, PAF88, PAF42, PAF66, PAF57 | |

| Only bureaucracy | Nothing will change, it is just another bureaucracy | PAF86, PAF23, PAF57, PAF81 | |

| Is increasing real restrictions | This is a movement to increase real restrictions and enforcement of environmental regulation | PAF68, PAF03, PAF01, PAF72 | |

| Is increasing perception of restrictions | CAR is making people think they will have to comply | PAF77 | |

| Made people more aware of environmental legislation | The registration process in CAR made people more aware of what was required in the Forest Code | PAF56, PAF68, PAF33, PAF50, PAF03, PAF18, PAF88, PAF77, PAF17, PAF66, PAF64, PAF55 | |

| Was too much information, already forgot | While registering in CAR advisors gave too much information and the interviewee even forgot it | PAF89 | |

| Did because goes together with everybody | Everybody did it, so the landowner did it too | PAF18, PAF63 | |

| CAR can help legalization | CAR has instruments to help to legalize the property | PAF31 | |

| 17. Emergent | Necessity drives decision-making process | Necessity is the main driver of decision-making process | PAF82 |

| Does not use the forest | I never walk in the forest | PAF82 | |

| Television as a source of environmental information | Television teaches about environment and environmental regulations | PAF82 | |

| Lack of sewage treatment in the municipality | Sewage treatment has an important impact water and the municipality does not take care of it | PAF71 | |

| People need to understand for themselves | The environmental campaigns have led to people to think and to understand the reasoning for conservation | PAF71 | |

| Participates in the rural labor union because s/he has employees | Main reason to participate in the labor union is that the individual has employees | PAF78 | |

| Criminal fires set | People always make fires in the road, and nobody knows who did it | PAF78, PAF03, PAF10 | |

| Used network to obtain public benefits | Used the network to obtain benefits | PAF56 | |

| Property is the first place to release animals in Rio de Janeiro | Private Reserve of Natural Heritage (RPPN) within property is the first place to release animals in Rio de Janeiro | PAF50 | |

| “Biodigestor” as a reason to join the project | Another reason to participate not related to land use was the inclusion of biodigestors in the project | PAF28 | |

| Water availability reduced | Remembers when the river had more water | PAF18 | |

| Government should invest in policies to keep the people in rural areas | People are leaving the rural areas because there are no options there | PAF06 | |

| RPPN | Created a protected area within property | PAF40, PAF50, PAF64, PAF54 | |

| Created an environmental NGO | Created an environmental NGO | PAF50, PAF51 | |

| Was harder was to convince the family to participate | The family did not want to participate because they believed it was unnecessary | PAF04 | |

| River is very dirty | There is a chicken producer that seems to pollute the river intensely | PAF73, PAF14 | |

| Birds are coming back with the prohibitions of cages | Perceived increase in bird population and believes this is due to the increased prohibition of cages | PAF08, PAF34 | |

| Expansion of the cities, land division into condominium | It is necessary to think how to stop the expansion of the cities, and land division into condominiums. The division is resulting in deforestation | PAF08 | |

| Absence of government | Does not work to report bad actions because the government does not do anything | PAF81 | |

| Bureaucracy in excess to obtain license | There is too much bureaucracy required to obtain a license to make a lake for raising fish. | PAF81, PAF72 |

| Topic | First-Level Code | Idea It Captures | Codes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Reasons for owning the land | Property for livelihood | Family depends on the property for livelihood, main source of family income | N1, N3, N7, N8, N10, N16, N19, N17, N20, N23, N26, N30 |

| Property was already in the family | When they started managing the property it already had the current use | N4, N22, N21 | |

| Property as additional source of family income | Property helps family income | N4 | |

| Property for leisure uses | Has the property for leisure purposes | N18, N19, EX70 | |

| Property as an investment | Bought property as a safe investment | N16, EX92 | |

| Property as a retirement Plan | Bought the property thinking about using it in retirement | N11, N19 | |

| Housing | Has the property only for family residence | N12 | |

| 2. Aims for the land | Property for family livelihood | Aims to provide for the family with property | N17, N1, N3, N7, N8, N30, N18, N19, N20, N22, N26, N23 |

| Bar on the property | Has a bar to complement income | EX70 | |

| Improve income from the property | The aim is to improve income for the property | N3, N4, N10 | |

| Limited labor changed the aim for the property | Had to change the aim due to restricted availability of labor | N10, EX70 | |

| Cattle drives decision making in the property | Sees cattle as a best source of investment and wants to keep cattle, which drives decision making | N16, N26 | |

| Use for leisure | Uses the property for leisure and wants to keep doing so | N11, N9 | |

| Property for housing | Property for housing purposes only | N18, N12, N9 | |

| Future income | Aims to get some income from the property in the future | N11 | |

| Additional income | Wants to keep the additional income from the property | N20 | |

| Condominium | Wants to transform the property in a condominium | N20 | |

| Property to leave something for the kids | Property to leave something for the kids | EX92 | |

| The bad roads are a problem for production | The bad roads are a problem for production | EX92 | |

| 3. Reason to maintain forest | Was already there | When landowner started managing the property the forest was already there | N17, N30, N18, N16, N10, N8, N19 |

| Needs forest because of law | The law requires having forest | N17, N3, N7, N12 | |

| Hunt | Likes to hunt, so maintained forest for hunting | N17 | |

| Likes the animals | Likes the animals, so maintained forest for animal life | N17, N21 | |

| Forest gives better environment | Forest gives a better environment on the farm, it is better to work more closely with the environment | N17, N7 | |

| Family teaching | The family already conserved forest and passed on this legacy | EX70 | |

| Acknowledges the law | Meet legal requirements | N1, N7, N30, N18, N10 | |

| Wood source | Maintain forest for wood source | N1 | |

| Water source | Maintain forest for water source | N1, N4, N7, N22, N20, N19, N16, N12, N11, N10, EX70 | |

| Likes the forest | Likes the forest | N4, N9, N19 | |

| Without the law would have the same amount of forest | The environmental law did not increase the amount of forest that the landowner has | N1 | |

| Stopped deforesting because of the law | When they heard the law was created, they stopped deforesting | N3 | |

| Produces banana within the forest | Maintains forest because s/he believes that banana productivity is higher within the forest | N23 | |

| Collaborate with society | Maintains forest because/he believes this is a way to collaborate with society | N26 | |

| Environmental awareness | Maintains forest because s/he considers him/herself to be an environmentally aware person and sees it importance | N21, N19, N11 | |

| Religious TV shows importance of nature | The religious TV stations talk about how forest is important for life | EX70 | |

| 4. Reason to restore forest | Shade for cattle | Allowed tree regrowth in some spots to provide shade for the cattle | N17 |

| Banana trees near the river | Aims to plant bananas to accumulate water | N1 | |

| No need to restore | Believes already has enough forest so they do not need to reforest | N3, N30, N8, N18 | |

| Wants to restore around springs | Wants to restore forest around springs to maintain water quality and availability | N7, N21, N22, N12 | |

| Pit areas | Allowed forest to grow back in pit areas | N26, N19 | |

| Animals | Planted because believed the animals needed more forest | N21 | |

| Lack of labor | Forest grew back in some areas due to lack of labor force | N23 | |

| Went to prison for deforestation | Was jailed because the employees were deforesting | N23 | |

| Recover degraded area | Let the forest grow back to recover a degraded area | N19, N19 | |

| Land abandonment | Forest grew back in areas are no longer in use | N9 | |

| 5. Perceived benefits of forest | Believes forest is important for water | Relates forest to water (provision and/or availability) and humidity | N17, N1, N3, N4, N23, N30, N21, N23, N22, N11, N9, N8, N10, N19, N12, N18, N20, EX70, EX92 |

| Believes forest does not increase water availability | People normally say that it is necessary to keep forest around springs, but the landowner does not believe that this is true | N26 | |

| Climate | The forest is important for lower temperatures and climate stability | N17, N4, N30, N20, N10, EX92 | |

| Hunting and leisure | Uses the forest to hunt, a source of recreation | N17 | |

| Wood | Used the forest as a wood source | N1, N21, N11, N9, N8 | |

| Air quality | Believes the forest is important for air quality purposes | N3, N4M N30, N21, N26, N22, N12, EX92 | |

| Erosion control | Believes the forest is important for erosion control purposes | N19 | |

| Forest conservation | Believes the forest is important for forest conservation purposes and sees this as a benefit | N30 | |

| Beauty and peace | Mentioned the beauty and the peace that forest provide as benefits | N26, N10, EX70 | |

| Palm/food | Eats palm from forest | N20 | |

| Plants within forest | Plants within forest to increase productivity | N23 | |

| 6. Perceived drawbacks of forest | Problems with hunters or palm extractors | The forest attracts people who hunt and extract palm | N17, N10, EX92 |

| No drawbacks at all | The forest does not produce any drawbacks, demonstrated strong denial of any drawback | N1, N23 | |

| Forest increase would impact livelihood | If I had to increase the forest area in my land, it would impact my family’s livelihood | N26 | |

| Forest around all rivers | Does not make sense to have forest around all rivers | N30 | |

| 7. Land management resulting in land use changes | Deforested in the past for cattle | Deforested to increase area for cattle | N9 |

| Changed the native pasture for bracquiaria to improve pasture | Change the native pasture for bracquiaria to increase productivity, invested in improving pasture | N1, N11 | |

| 8. Discovery of PAF | Project visited the property | Project staff has been to the property to offer PAF | N17, N3 |

| EMATER | Heard about it at the technical institute | N1, N4 | |

| Neighbors participating | Found out about the project because neighbors were participating | N19, N9 | |

| Part of COMDEMA | Member of the municipality environment committee | N26 | |

| TV | Saw a program on television | N11 | |

| Local institution | Heard something about it in one of the local institutions (EMATER Rio Claro), or the rural labor or environmental secretariats | N22, N20, N16, N12, N30 | |

| Project | Follows the project since the beginning | N21 | |

| Project went until property | The project staff visited the property to explain the project | N10 | |

| 9. Motivation not to participate | Not convenient | PAF was not convenient | N17, N4 |

| Low payment | PAF does not cover opportunity costs of reforesting | N17, N26, N16, N20 | |

| Uncertainty about future of the project | They pay now, but who guarantees that the project will keep paying in the future | N17 | |

| Heard about it but nobody offered it | Heard about it, but did not want to follow up to see if it a good deal | N1, N10 | |

| Would reduce agricultural production | The reforestation would reduce production | N3, N26, N16, N20, N22, N8 | |

| If reforestation were mandatory s/he might participate | Would participate if reforest if was mandatory | N22, N26 | |

| If could decide the places to be reforest would join | Could join the project if s/he could choose the places to reforest | N30 | |

| Could consider increasing the % missing from the LR | Might consider participating to increase the % of forest needed to be in compliance with the LR | N26 | |

| Was not directly offered to join | Was not directly offered opportunity to join so did not think much about joining, but from the description provided, might have joined | N30, N19, N12 | |

| Does not want to reforest | Does not want to reforest | N18 | |

| Was already doing | Was already doing what the project is supposed to do so did not see any reason to join; sees it as doing his/her part. | N11 | |

| Would participate if needed to add to participation | If people asked individual to participate s/he would join to contribute with the people | N30, N11 | |

| Does not believe in the project | Does not believe in the project because people only “give the worse part of the property to the project” | N21 | |

| It would be like selling a part of the land | Believes that participating on PAF would be like selling a part of the land | N10 | |

| Small property | Property is too small to reforest part of it | N11, N9, N8 | |

| Contract time | The contracts are for less than 5 years and reforestation is forever | N20, N8 | |

| Does not trust the government | Does not trust the government and believes they would not keep their word and would stop paying whenever | N16, N20 | |

| Left the project because the project wanted to plant in the riparian forest | Family decided left the project because the project wanted to plant riparian forest and they thought they already had too much forest, cancelled enrolment when found out about the reforestation requirement | EX70, EX92 | |

| Wanted to participate for the money | Money drove participation | EX70, EX92 | |

| Land already retains a lot of water and owner should be paid for that | S/he believes the property already produces a lot of water, and s/he should be paid for that | EX92 | |

| 10. What would you require to reforest | Nothing, farm is too small | Would not reforest because farm is too small | N17 |

| Higher and payment in perpetuity | The payments would have to be higher and paid in perpetuity | N17 | |

| Only if was mandatory | Would only reforest if was mandatory | N22, N26 | |

| 11. Perception of outcomes | Not Applicable to Non-Participant Group | ||

| 12. Knowledge of environmental regulations | Deforestation is prohibited | Deforestation is not allowed | N17, N8, N9, N10, N12, N16, N18, N22 |

| Need riparian forest | It is necessary to have forest around rivers | N17 | |

| Fire is prohibited | It is not allowed to use fire to manage the land | N17, N1, N4, N22, N12, N8 | |

| Hunting is prohibited | Hunting is not allowed | N23 | |

| Chemicals are prohibited | Using chemicals near the river is not allowed | N22 | |

| Knows that small landowners have fewer requirements | Small landowners have fewer obligations than big ones in the Forest Code | N17, N30 | |

| Knows about PPA and LR | Is aware of PPA and LR requirements | N17, N1, N3, N4, N22, N26, N30, N18, N16, N12, N11, N10, N8, EX70 | |

| Palm extraction is prohibited | It is prohibited to extract palm | N4, N23 | |

| Aware of law | Mentioned following and knowing about the environmental law | N21, EX92 | |

| Not allowed to touch anything | The law does not allow to the landowner to extract or deforest anything in the forested land | N26, N23, N12 | |

| Never worried too much because believes conservation is important | Did not look to find out about environmental regulations because do not want to act against the environment | N19 | |

| Changes too much | The environmental law changes too much, so it is hard to follow | N30 | |

| 13. Opinion of environmental regulations | Conservation is important | Thinks the regulations are important because conservation is important | N1, N3, N4, N21, N12 |

| Good, but inefficient | Believes that the legislation is good, but most people do not follow the rules | N17 | |

| Differences between small and large landowners | The big landowners deforested around rivers more; there is a difference in the way agents enforce the regulations in big vs. small properties | N17, N12, N11 | |

| Important for environment | Believes environmental regulation is important for the environment | N1 | |

| Much more deforestation would occur without regulation | Without the law would exist much more deforestation | N3, N4, N7, EX70 | |

| What exists is enough | It is not necessary to ask landowners to reforest more if the producer already has 20% of land in forest | N7 | |

| The regulations are not in line with the rural reality | The law does not match the rural reality | N30 | |

| Some regulations are excessively demanding | Believes that some environmental regulations are excessive and go beyond what is necessary | N23, N16, N12 | |

| The legal regulations are not a factor in decision-making | The landowners do not consider the law for decision making | N22 | |

| People would deforest if the regulations did not exist | If the law did not exist, people would cut everything down to put pasture | N12, N9 | |

| It is important for protecting water | Forested land is important in retaining water and therefore the regulation is important | N26, N22, N8 | |

| Corruption | The state is the first to not follow the rules | N16 | |

| Small landowners incapable to comply | Small landowners cannot maintain forest because compliance would mean that would be no land for production | N18 | |

| Protecting hilly lands makes no sense | The Atlantic forest occupies hilly terrain and it makes no sense to protect all of the hill terrain | N18, N20 | |

| 14. Perceived enforcement of environmental regulations | Some enforcement | Sees the enforcement car pass, but does not know anyone that was fined | N17, N1, N26, N20, N12, N11 |

| Only for the small | Big landowners are often unpunished | N3 | |

| Corruption of the agent | Mentioned that knows about enforcement agencies being corrupt, the corruption allows the bribers to get away with environmental crimes | N7, EX70 | |

| Park area | Is within protected area so gets to see more enforcement | N10 | |

| Rigor in enforcement in relation to deforestation | Reported that enforcement of the legislation has been strict or knows people that were fined | N16, N10 | |

| Never saw law enforcement | Reported that never saw or heard about law enforcement actions | N18, N19, N8 | |

| The places with bad roads do not get any enforcement | The places with bad roads do not get any enforcement | N9 | |

| Fines do not affect behavior | Does not think fines affects the behavior of people, because they know people who were fined and did not change their behavior at all | N12 | |

| Does not worry about it | Agrees with it and does not worry about it | N19 | |

| Was jailed before | Was jailed for environmental crimes (deforestation) | N23 | |

| Believes does not see enforcement in the region because the deforestation is over | Believes does not see enforcement in the region because the deforestation is over in the region | N30 | |

| Enforcement in bird caging has increased and know there are more birds | The enforcement of people that practice bird caging has increased and knows there are more birds now | EX70 | |

| Contributed to people leaving rural areas | Believes the rigor in the environmental law contributed to people moving away from rural areas | EX70 | |

| The law is important because otherwise there would be more deforestation | Believes the law has slowed or prevented more deforestation | EX70 | |

| 15. Perceived motivations to comply (or not) with environmental legislation | Normative motivations. Agrees with the law or believes is the right thing to do | Complies with environmental law because believes is the right thing to do | N17, N3, N7, N30, N26, N19, N18, N12, N10, N9, N8, N22 |

| Fear of enforcement | Believes people conserve because they fear enforcement will show up | N1, | |

| Normative motivations | Believe all citizens must follow any rule | N1 | |

| Calculated motivations | People do not comply because there is not enough enforcement | N3, N7, N22, N30, N21, N19, N18, N12, N11, EX70 | |

| People believe that will not be sanction | People are aware of the law, but do not think there will be sanctions | N21, N18, N22 | |

| Bad example of the government | People do not comply because they have a bad example of the government | N18 | |

| People do not know why is important to have forest | People do not know why is important to have forest, so they do not comply | N26 | |

| Necessity of each family | The decision over the land is independent from the legislation and change with the necessity of each family | N30 | |

| 16. CAR perception of change in environmental regulations and in enforcement | Nothing will change | CAR will not change anything in terms of land management or enforcement | N17, N21, N 18, N16, N11 |

| Made people more aware of environmental legislation | The registration process in CAR made people more aware of what was required in the FC and of their rights | N17, N3 | |

| Did the Car because had too | Did the Car because had too, did not learn anything with it | N1, N19, N18, N10, N9, N8. N20, N22, N23 | |

| Will increase real requirements | Believes the government will later start asking landowners to reforest | N3, N30, N26, EX92 | |

| Diagnostic | Believes is a good way to the government to find out about rural areas | N7 | |

| Only bureaucracy | Nothing will change it is just another bureaucracy | N21, N10 | |

| Depends on political will | CAR seems to be a good instrument, but its application will depend on the will of politicians, and corruption is institutional | N12, N16 | |

| 17. Emergent | Participates in Rio Rural | Participates in a World Bank project that requires “an environmental” action | N1 |

| Fire is normally a crime | Someone has set a fire and the fire entered the property | N1 | |

| Heard about the RPPN project, and did not participate because of the family | Mentioned PES from RPPN and only did not join because property was in family name | N3 | |

| “Clear” land is necessary | It is necessary to clean the land every two years, otherwise you lose the right of using it | N22 | |

| Sewage from the property goes to the river | Property owner reported that the sewage from the property goes to the river | N8 | |

| Have cows to maintain the pasture | Cows avoid forest to grow back, and help to maintain the pasture | EX70 | |

| Corruption with bureaucracy to legalize water extraction | The producer gave up of a project because it had Corruption with bureaucracy to legalize water extraction | EX92 | |

| Theme | First-Level Code | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Property for leisure | ||

| Property for leisure | 1 | |

| Property to share with friends | 1 | |

| Desire to pursue a rural way of life | 1 | |

| Family had the property for leisure use | 1 | |

| Family likes the region and the property | 1 | |

| Looking for escape from the city | 1 | |

| Family dream | 1 | |

| Housing | 1 | |

| Inspiration | 1 | |

| Identifies with indigenous culture | 1 | |

| Forest conservation | 1 | |

| Property for forest conservation | 2 | |

| Use for leisure | 2 | |

| “Arrenda” for maintenance | 2 | |

| Enjoys the forest | 3 | |

| Land abandoned in areas that were not being used | 4 | |

| Let forest regrow | 7 | |

| Was pasture when arrived | 7 | |

| Property as additional income | ||

| Property as investment | 1 | |

| Property as inheritance | 1 | |

| Property as additional income in hard time | 1 | |

| Retirement plan | 1 | |

| Raise horses | 1 | |

| Family already managed the property before current owner | 1 | |

| Cattle | 2 | |

| Additional income | 2 | |

| Tourism | 2 | |

| Bar on the property | 2 | |

| Changed from agricultural production to tourism | 4 | |

| Forest as additional source of income (subtheme) | ||

| Off-site mitigation | 4 | |

| Desire to own something in a forested area | 9 | |

| Property as main source of income | ||

| Property for cattle ranching | 1 | |

| Family livelihood is related to the property | 1 | |

| Family already managed the property | 1 | |

| Property provides family livelihood | 2 | |

| Aims to improve the property | 2 | |

| Cattle | 2 | |

| Deforested in the past for cattle | 7 | |

| Transformed property into a condominium | 7 | |

| Perception of restrictions and limitations reduces property profitability | ||

| Labor limitations | ||

| Labor limitations changed the aim for the property | 2 | |

| Aging | 2 | |

| Labor expenses | 3 | |

| Legal restrictions | ||

| Property in a park area | 2 | |

| Use property for leisure because cannot alter it | 2 | |

| Too many restrictions on use of forest land | 6 | |

| The landowner has more responsibility over forest land than over pasture | 6 | |

| Not allowed to alter anything in forested areas | 12 | |

| Law prevents owner from profiting from the property | 13 | |

| Park area | 14 | |

| Infrastructure restrictions | ||

| Difficult access | 2 | |

| Tried activities that did not work | 2 | |

| Legal restrictions are not enforced in areas with bad roads | 14 | |

| Corruption causes ineffectiveness | ||

| Corruption prevented implementing economic activity | 2 | |

| Money attracts corruption | 9 | |

| NGO responsible for reforestation needs to be audited | 10 | |

| More rigor by the executor of the program is necessary | 10 | |

| Some additional regulations are overdue | 13 | |

| Sanctions are not complete and corrupts citizens | 15 | |

| Corruption differs between big and small landholders | 13 | |

| Corruption of enforcement agents | 14 | |

| Individuals use the network to obtain public benefits | 17 | |

| Water | ||

| Maintain forest because of water | 3 | |

| Areas around spring | 4 | |

| Believes forest in important for water | 5 | |

| Conservation is important | 13 | |

| Water availability is reduced over time | 18 | |

| To protect springs | 9 | |

| Social motivations for pro-environmental action | ||

| Obligation as a citizen | 3 | |

| Maintain forest for benefit of future generations | 3 | |

| Societal collaboration | 5 | |

| Everybody around was participating, so joined too | 9 | |

| Project people were nice | 9 | |

| The project sounded important | 9 | |

| Recognition | 9 | |

| Benefit for others | 9 | |

| Worked in the project | 10 | |

| Any law must be respected | 13 | |

| Did because it brings together everybody | 16 | |

| Laws promote pro-environmental action | ||

| Maintain forest because is cutting is not allowed | 3 | |

| Law is required | 3 | |

| Looked for help to restore land in order to fulfill environmental regulation | 8 | |

| Joined PAF because of legislation | 9 | |

| Direct use of the forest/forest utilities | ||

| Water | ||

| Wood source | 3 | |

| Firewood | 5 | |

| Reduce the problems with fire | 4 | |

| Erosion control | 5 | |

| Clear air | 5 | |

| Desire to restore areas | 9 | |

| Environmental awareness and biospheric values | ||

| Environmental awareness | 3 | |

| Maintain forest because of animals | 3 | |

| Believes forest is important for conservation | 5 | |

| Would have joined without the money | 9 | |

| Increase local environmental awareness | 9 | |

| Forest conservation | 1 | |

| Never worried much because s/he believes conservation is important | 12 | |

| Conservation is important | 12 | |

| Normative motivations: Agrees with the law or believes compliance is the right thing to do | 13 | |

| It is necessary to understand the reasoning behind environmental laws | 15 | |

| Intrinsic motivation for pro-environmental action | ||

| Religion | 3 | |

| Trees are beautiful | 4 | |

| Sponsorship for increases in protection | 9 | |

| Increases local environmental awareness | 9 | |

| Likes forest | 9 | |

| Forest conservation | 1 | |

| Forest provides peace and beauty, stress relief | 5 | |

| Forest provides inspiration for work | 5 | |

| People need to understand for themselves | 17 | |

| Recover previous damage to the land | ||

| Recovered a degraded area | 4 | |

| Relieved guilt for past deforestation | 9 | |

| Positive environmental outcomes | ||

| Land was abandoned areas that were not being used | 4 | |

| Changed agricultural production to tourism | 4 | |

| Wanted to restore and could not do it alone | 9 | |

| Perception of positive outcomes | 9 | |

| Became aware of the importance of forest and stopped deforesting | 10 | |

| Stopped harvesting wood from the forest because of PAF | 10 | |

| Increased water availability | 10 | |

| Reduced erosion | 10 | |

| Reduced the problems with fire | 10 | |

| People would deforest if it did not exist | 13 | |

| Changed behavior because increase the perception of enforcement | 14 | |

| Illegality/impunity and lack of government as example | ||

| Problems with hunters or palm extractors | 6 | |

| Avoid criminal fire and hunting | 9 | |

| Avoid land invasion | 9 | |

| People believe that there will not be any sanction | 15 | |

| Sanctions are not complete and corrupts the citizenry | 15 | |

| The government itself does not do anything | 13 | |

| Corruption of the enforcement agents | 14 | |

| Fines are not paid | 14 | |

| Nothing will change | 16 | |

| Depends on political will | 16 | |

| Sewage treatment is lacking in the municipality | 17 | |

| Criminal fires occur (arson) | 17 | |

| Absence of government | 17 | |

| No required behavior change | ||

| Already was complying with the law and would get money for it as well | 9 | |

| No reason not to join | 9 | |

| No negative impact | 9 | |

| No behavior change | 10 | |

| Nothing was done by PAF in the property | 10 | |

| The change in the property did not impact production | 10 | |

| Calculated motivations | ||

| Money | 9 | |

| Believes in the PES logic | 9 | |

| Used the term rent for PAF | 9 | |

| Calculated motivations | 15 | |

| People believe that there will not be sanctions | 15 | |

| People would deforest the law did not exist | 13 | |

| Fine is too high | 14 | |

| People live today and do not worry about tomorrow | 15 | |

| Necessity is critical in the decision-making process | 17 | |

| (subtheme) Autonomy | ||

| Contract flexibility | 9 | |

| RPPN immobilizes the land | 17 | |

| (subtheme) Costs related to land management | ||

| For help with fencing | 9 | |

| Reduce cost of required reforestation | 9 | |

| Not drawbacks, but costs with fencing is costly | 6 | |

| Reduced utility in acting against the law | ||

| Rigor in the enforcement in relation to hunting | 14 | |

| Rigor in the enforcement in relation to deforestation | 14 | |

| Fine is too high | 14 | |

| Changed behavior because of increased perception of enforcement | 14 | |

| Is increasing real restrictions | 16 | |

| Is increasing perception of restrictions | 16 | |

| CAR can help legalization | 16 | |

| Bureaucracy | * moved to be facility easiness | dropped |

| Help to avoid tax fine | 9 | |

| Bureaucracy cost of compliance with environmental regulation | 15 | |

| Overlap of legislation | 13 | |

| Overlap of enforcement in different levels of government | 14 | |

| Only bureaucracy (effort associated with land registration) | 16 | |

| Bureaucracy in excess to obtain license | 17 | |

| Land value as a reason not to conserve | ||

| Nothing for heirs | 6 | |

| Expansion of the cities, land division into condominium | 17 | |

| Unfairness | ||

| The enforcement agents do not know how to communicate with landowners | 14 | |

| Corruption: Difference in enforcement actions taken with small and large landowners | 13 | |

| Awareness (dropped) | ||

| Made people more aware of environmental legislation | 16 | |

| Is aware of PPA and RL | 12 | |

| Increased environmental awareness in the country | 12 | |

| Not allowed to touch anything | 12 | |

| Does not know anything | 12 | |

| Deforestation is not allowed | 12 | |

| Fire is not allowed | 12 | |

| Toxic chemicals are not allowed | 12 | |

| Aware of rules | 12 | |

| Not allowed to extract river sand | 12 |

| Theme | Action |

|---|---|

| Property for leisure | Rational to have a property |

| Property as additional income | Rational to have a property |

| Property as main source of income | Rational to have a property |

| Perception of restrictions reduces property profitability | Keep |

| Labor restrictions | |

| Law restrictions | |

| Infrastructure restrictions | |

| Corruption causes ineffectiveness | Joined into illegality |

| Water | It is part of intrinsic calculations and social motivations |

| Social motivations for pro-environmental action | Keep |

| Laws promote pro-environmental action | Keep |

| Direct use of the forest/forest utilities | Part of calculated motivations |

| Environmental awareness/biospheric values | Part of intrinsic motivations and of how law restrictions are perceived |

| Intrinsic motivation for pro-environmental action | Keep |

| Recover previous damage to the land | Reflects change in intrinsic and/or social motivations to act |

| Positive environmental outcomes | Keep |

| Illegality/impunity and lack of government as example | Joined with corruption |

| No required behavior change | Keep |

| Calculated motivations | Keep |

| (subtheme) Autonomy | |

| (subtheme) Costs related to land management | |

| Reduced utility in acting against the law | Keep |

| Bureaucracy | Included in calculated motivations and in the perception of corruption and Illegality |

| Land value as a reason not to conserve | Included in calculated motivations |

| Unfairness | Keep |

| Awareness | Dropped once the change in awareness about the law does not reflect in the change in behavior |

| Easiness | Keep |

References

- Van Zanten, B.T.; Verburg, P.H.; Espinosa, M.; Gomez-y-Paloma, S.; Galimberti, G.; Kantelhardt, J.; Raggi, M. European agricultural landscapes, common agricultural policy and ecosystem services: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karsenty, A.; Aubert, S.; Brimont, L.; Dutilly, C.; Desbureaux, S.; Blas, D.E.; Le Velly, G. The economic and legal sides of additionality in payments for environmental services. Environ. Policy Gov. 2017, 27, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Meyfroidt, P.; Rueda, X.; Blackman, A.; Börner, J.; Cerutti, P.O.; Dietsch, T.; Jungmann, L.; Lamarque, P.; Lister, J.; et al. Effectiveness and synergies of policy instruments for land use governance in tropical regions. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 28, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.; Gaskell, P.; Ingram, J.; Dwyer, J.; Reed, M.; Short, C. Engaging farmers in environmental management through a better understanding of behaviour. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börner, J.; Kis-Katos, K.; Hargrave, J.; König, K. Post-crackdown effectiveness of field-based forest law enforcement in the Brazilian Amazon. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, I.; Schröter-Schlaack, C. Justifying and assessing policy mixes for biodiversity and ecosystem governance 1544. In Instrument Mixes for Biodiversity Policies; POLICYMIX Report, Issue No. 2/2011; UFZ—Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research: Leipzig, Germany, 2011; pp. 14–35. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, D.N.; Blumentrath, S.; Rusch, G. Policyscape—A spatially explicit evaluation of voluntary conservation in a policy mix for biodiversity conservation in Norway. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 1185–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börner, J.; Wunder, S.; Wertz-Kanounnikoff, S.; Hyman, G.; Nascimento, N. Forest law enforcement in the Brazilian Amazon: Costs and income effects. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 29, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robalino, J.; Sandoval, C.; Barton, D.N.; Chacon, A.; Pfaff, A. Evaluating interactions of forest conservation policies on avoided deforestation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Tort, S. Payments for ecosystem services and conditional cash transfers in a policy mix: Microlevel interactions in Selva Lacandona, Mexico. Environ. Policy Gov. 2019, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.; Heimlich, J.; Braus, J.; Merrick, C. Influencing Conservation Action: What Research Says about Environmental Literacy, Behavior, and Conservation Results; National Audubon Society: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heimlich, J.E.; Ardoin, N.M. Understanding behaviour to understand behaviour change: A literature review. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behaviour. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heukelom, F. Behavioral Economics: A History; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lapeyre, R.; Pirard, R.; Leimona, B. Payments for environmental services in Indonesia: What if economic signals were lost in translation? Land Use Policy 2015, 46, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, G.G.; Fantini, A.C.; Salvador, C.H.; Farley, J. Additionality is in detail: Farmers’ choices regarding payment for ecosystem services programs in the Atlantic forest, Brazil. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 54, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, L.L.; Farley, K.A.; Lopez-Carr, D. What factors influence participation in payment for ecosystem services programs? An evaluation of Ecuador’s SocioPáramo program. Land Use Policy 2014, 36, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansing, D.M. Understanding smallholder participation in payments for ecosystem services: The case of Costa Rica. Hum. Ecol. 2017, 45, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwayu, E.J.; Paavola, J.; Sallu, S.M. The livelihood impacts of the Equitable Payments for Watershed Services (EPWS) Program in Morogoro, Tanzania. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2017, 22, 328–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rode, J.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Krause, T. Motivation crowding by economic incentives in conservation policy: A review of the empirical evidence. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 117, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosoy, N.; Corbera, E.; Brown, K. Participation in payments for ecosystem services: Case studies from the Lacandon rainforest, Mexico. Geoforum 2008, 39, 2073–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, T.M. Carbon forestry and agrarian change: Access and land control in a Mexican rainforest. J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 859–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, L.; Speelman, S.; Aguirre, N. Farmers’ preferences for PES contracts to adopt silvopastoral systems in southern Ecuador, revealed through a choice experiment. Environ. Manag. 2017, 60, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegde, R.; Bull, G.Q.; Wunder, S.; Kozak, R.A. Household participation in a payments for environmental services programme: The Nhambita forest carbon project (Mozambique). Environ. Dev. Econ. 2015, 20, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Polinsky, A.M.; Shavell, S. On the disutility and discounting of imprisonment and the theory of deterrence. J. Leg. Stud. 1999, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Winter, S.C.; May, P.J. Motivation for compliance with environmental regulations. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2001, 20, 675–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wünscher, T.; Engel, S.; Wunder, S. Spatial targeting of payments for environmental services: A tool for boosting conservation benefits. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbera, E.; Kosoy, N.; Martínez Tuna, M. Equity implications of marketing ecosystem services in protected areas and rural communities: Case studies from Meso-America. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2007, 17, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petheram, L.; Campbell, B.M. Listening to locals on payments for environmental services. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 1139–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil. Lei No 12.651, 25 De Maio De 2012. 2012. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2011-2014/2012/Lei/L12651.htm (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Brancalion, P.H.S.; Lamb, D.; Ceccon, E.; Boucher, D.; Herbohn, J.; Strassburg, B.; Edwards, D.P. Using markets to leverage investment in forest and landscape restoration in the tropics. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 85, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, R.B.; Durigan, G.; Brancalion, P.H.S.; Aronson, J. On the need of legal frameworks for assessing restoration projects success: New perspectives from São Paulo state (Brazil): Legal instruments for assessing restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2015, 23, 754–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparovek, G.; Barretto, A.G.; Matsumoto, M.; Berndes, G. Effects of governance on availability of land for agriculture and conservation in Brazil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 10285–10293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparovek, G.; Berndes, G.; Barretto, A.G.; Klug, I.L. The revision of the Brazilian Forest Act: Increased deforestation or a historic step towards balancing agricultural development and nature conservation? Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 16, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castello Branco, M.R. Pagamento Por Serviços Ambientais: Da Teoria à Prática/Maurício; ITPA: Rio Claro, Brazil, 2015; p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- IBGE—Instituto Brasileiro De Geografia e Estatística. Conheça Cidades e Estados do Brasil. 2017. Available online: https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/ (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- AGEVAP—Associação Pró-Gestão das Águas da Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio Paraíba do Sul. 2017. Available online: http://comiteguandu.org.br/publicacoes/boletim/boletim-digital-13.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- IBGE. Censo Agropecuário. 2017. Available online: https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/rj/rio-claro/pesquisa/24/76693 (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bazeley, P. Qualitative Data Analysis: Practical Strategies; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DiCicco-Bloom, B.; Crabtree, B.F. The qualitative research interview. Med Educ. 2006, 40, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halcomb, E.J.; Davidson, P.M. Is verbatim transcription of interview data always necessary? Appl. Nurs. Res. 2006, 19, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, H.R.; Ryan, G.W. Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Felding, L. Handling Qualitative Data, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, L.C.; Fischhoff, B. Injury prevention and risk communication: A mental model approach. Inj. Prev. 2012, 18, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Northcutt, N.; McCoy, D. Comparisons, interpretations, and theories: Some examples. In Interactive Qualitative Analysis; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2004; pp. 394–424. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, M.; Shlonsky, A. Systematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, V.R. PSA Hídrico da Bacia do Guandu/RJ: Aonde Levará o Mercado Que Pretende Salvar a Floresta e a Água? Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Instituto de Pesquisas e Planejamento Urbano e Regional Programa de Pós-Graduação em Planejamento Urbano e Regional: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2017; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Bulte, E.H.; Lipper, L.; Stringer, R.; Zilberman, D. Payments for ecosystem services and poverty reduction: Concepts, issues, and empirical perspectives. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2008, 13, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pagiola, S.; Arcenas, A.; Platais, G. Can payments for environmental services help reduce poverty? An exploration of the issues and the evidence to date from Latin America. World Dev. 2005, 33, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagiola, S.; Rios, A.R.; Arcenas, A. Can the poor participate in payments for environmental services? Lessons from the Silvopastoral Project in Nicaragua. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2008, 13, 299–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Motta, R.S.; Ortiz, R.A. Costs and perceptions conditioning willingness to accept payments for ecosystem services in a Brazilian case. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 147, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.; Porras, I.T.; Moreno, M.L. The Social Impacts of Payments for Environmental Services in Costa Rica: A Quantitative Field Survey and Analysis of the Virilla Watershed; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zbinden, S.; Lee, D.R. Paying for environmental services: An analysis of participation in Costa Rica’s PSA program. World Dev. 2005, 33, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hecken, G.; Bastiaensen, J.; Vasquez, W.F. The viability of local payments for watershed services: Empirical evidence from Matiguas, Nicaragua. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 74, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wünscher, T.; Engel, S. International payments for biodiversity services: Review and evaluation of conservation targeting approaches. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 152, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzine-de-Blas, D.; Ruiz-Pérez, M. Análisis Multi-Dimensional De Pagos Privados y Del Sector Público Por Servicios Ambientales; SMEE: San José, Costa Rica, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa, F.; Caro-Borrero, Á.; Revollo-Fernández, D.; Merino, L.; Almeida-Leñero, L.; Paré, L.; Espinosa, D.; Mazari-Hiriart, M. “I like to conserve the forest, but I also like the cash”. Socioeconomic factors influencing the motivation to be engaged in the Mexican Payment for Environmental Services Programme. J. For. Econ. 2016, 22, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriagada, R.; Villaseñor, A.; Rubiano, E.; Cotacachi, D.; Morrison, J. Analyzing the impacts of PES programmes beyond economic rationale: Perceptions of ecosystem services provision associated to the Mexican case. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 29, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S.; Brouwer, R.; Engel, S.; Ezzine-de-Blas, D.; Muradian, R.; Pascual, U.; Pinto, R. From principles to practice in paying for nature’s services. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Toward a behavioral theory linking trust, reciprocity, and reputation. In A Vol. in the Russell Sage Foundation Series on Trust. Trust and Reciprocity: Interdisciplinary Lessons from Experimental Research; Ostrom, E., Walker, J., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 19–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, C.C.; Williams, J.T.; Ostrom, E. Local enforcement and better forests. World Dev. 2005, 33, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A.A.; Rajão, R.; Costa, M.A.; Stabile, M.C.; Macedo, M.N.; dos Reis, T.N.; Pacheco, R. Limits of Brazil’s Forest Code as a means to end illegal deforestation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 7653–7658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]