1. Introduction

Unchecked economic growth is no longer a viable alternative. In recent years, civil society, institutions, and governments have increasingly focused on the economic activity of companies, in the search for a more balanced economic system in which sustainability prevails over other results.

Thus, the growing interest in the activity of businesses—mainly since the recent severe economic and financial crisis—has generated growing expectations regarding the need for organizations to reverse their inefficiencies, moving towards more sustainable models that place people at the center of their activity and at the heart of their decision-making processes. Consequently, a framework has been created to drive the transformation of corporate management systems so that companies can combine their competitive strategies with new lines of governance which support the adjustment between business growth and responsible, sustainable growth. Institutional activities have not remained on the sidelines of this movement. On the one hand, various international bodies such as the European Union (EU) and the United Nations (UN) have introduced the social economy (SE) into their agendas and discourse as a model of organization that is especially propitious to the creation of quality employment, local development, the improvement of social welfare, and citizen empowerment [

1,

2,

3,

4]. On the other hand, national governments are increasingly concerned to promote sustainable economic and business development models that contribute to reversing the existing socio-economic imbalances [

5,

6].

In this context, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—adopted by the UN General Assembly in New York on 25 September 2015—provide a road map for change. The common denominator among these objectives is the need to reconcile economic growth with the sustainability of the system, which requires profound transformations in the management of organizations and their production processes. In short, the aim is to link commitment to the SDGs with the economic activities to be developed.

The SE has drawn attention to this process of change. With over 150 years of history, this alternative represents the solution to the rapidly changing demands, generating new business opportunities without ignoring the social aspect inherent in economic relations; equally, it is the means of achieving a more egalitarian, integral, and environmentally-friendly kind of development. The importance of the SE in fulfilling the SDGs has recently been recognized by the United Nations Task Force on Social and Solidarity Economy (UNTFSSE), Social Economy Europe (SEE), and Cooperatives Europe of the International Co-operative Alliance.

However, there is a dearth of empirical work (with the notable exception of Mozas, 2019) examining this relationship in order to determine its effect. Additional efforts are therefore needed to link the SE to progress in achieving the SDGs. This study addresses this research gap by examining this relationship from a theoretical point of view, focusing on those objectives most closely related to SE activity: the development of equal opportunities (SDG 5), the promotion of sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all (SDG 8), and the reduction of inequalities (SDG 10). This involves moving beyond the traditional approach based on environmental criteria [

7] (whereby the effects of commitment to sustainability are measured), to the sphere of economic activity, demonstrating how the latter can also contribute towards the attainment of SDGs.

Moreover, while the strategy of achieving sustainable and more people-centered growth must be implemented from the perspective of national governments, in many countries, such as Spain, these actions have recently been transferred to sub-central governments [

8,

9,

10]. It should be noted that according to the Spanish Constitution (1978), Spain is a regionalised State, also referred to as “Estado de las Autonomías”. Art. 143 in the Constitution foresaw the possibility to create Autonomous Communities. Galicia, with the Basque Country and Catalonia, were the first ones to adopt their own Statutes of Autonomy by using the procedure of Art. 151. According to Article 149.3, some matters may fall under the jurisdiction of the Autonomous Community, by virtue of their respective Statutes. For example, Autonomous Communities are responsible for the legislative development and implementation of the State legislation and for the Promotion of economic development within the frame of the national policy. In turn, the Statute of Autonomy of Galicia recognizes in article 55.3 the power of this Autonomous Community to make use of the powers provided in

Section 1 of article 130 of the Constitution, including the modernization and development of all economic sectors, which may boost them through its own legislation. By exerting this competence, Galicia approved its own Social Economy Act in 2016. Specifically, the autonomous community of Galicia in Spain was the first region to develop its own rules on the SE. Additionally, this territory has special socio-economic characteristics (high rates of ageing population, geographical dispersion, high population concentration in big cities and abandonment of rural areas); while these are not exclusive to this autonomous region, they represent elements of a new reality that can be extrapolated to other territories. Consequently, the exploration of the results obtained by the Galician community in terms of SE consolidation and its level of progress in achieving the SDGs could be decisive when weighing up possible solutions to the threats and distortions that this new socio-economic reality poses for the survival of the economic system.

Therefore, the objective of this article is to analyze the current situation of the SE in the autonomous community of Galicia as an instrument in meeting the SDGs. To do that, this paper draws on the scarce literature on the role of the SE in achieving SDGs to address the following research questions:

- (1)

What is the relationship between SDGs and SE?

- (2)

How can SE be fostered from a subnational approach?

- (3)

What are the links between the policies aimed to improve SE and the achievement of SDGs?

- (4)

Would a regional approach to foster SE be more effective than a national one to contribute to the achievement of SDGs?

To this end, the second section will relate the UN’s SDGs to the SE. The third section examines Galicia’s legislative initiatives in the field of the SE, since, as already observed, it is the first and only region in Spain to date with specific legislation in this area. Section four presents a review of the SE actions in Galicia regarding compliance with the SDGs. Section five identifies several recommendations, and finally, a number of conclusions are offered.

2. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and Their Relationship with the Social Economy

In September 2015, the UN General Assembly adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

11,

12], thus establishing an action plan for people, the planet and economic, social and environmental well-being. In this document, the UN indicated that the greatest challenge facing humanity is to eliminate poverty, which is only possible with sustainable growth, hence the need for an instrument that sets out the strategies of global development programs for the next fifteen years.

To this end, Agenda 2030 presents 17 SDGs, descendants of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The SDGs have 169 goals, with a clear integrative and indivisible vision pivoting around a threefold perspective: economic, social, and environmental (

Table 1). From a generic review of these objectives, it is evident that these goals are highly coherent with the principles of the SE; however, for the purposes of this work, we wish to highlight those most directly related to economic activity: achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls (SDG 5); promoting sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all (SDG 8); and helping to reduce inequalities (SDG 10).

The commitment to Agenda 2030 involves civil society, institutions, and those actors responsible for economic activity. However, the need to create a paradigm shift towards a competitive and sustainable economic system seems to have placed companies (the biggest players in economic activity) at the center of the transformations. In this regard, it should be recalled that the UN Global Compact (2000) already highlighted the need to promote corporate social responsibility, since companies’ actions have an impact on different interest groups and should, therefore, be guided by a civic responsibility that goes beyond strictly economic activity [

13]. In this sense, the concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR), understood as the duty on the part of companies to make decisions that strive for a balance between self-interest for the maximization of profit and social welfare [

14], can be considered to be the first step in the search for sustainable development through economic and entrepreneurial activity. Along these lines, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD [

15]) defines CSR as a business contribution to sustainable development.

The structure of the SDGs implies a greater level of responsibility on the part of companies for several reasons; in the first place, while the commitment made is by the governments of the signatory nations, the SDGs explicitly extend obligations to civil society and business organizations. Secondly, business and the private sector must play a role alongside governments and institutions, in order to achieve these objectives. Thirdly, while the SDGs are not binding, they will act as de facto regulation and will drive the implementation of national regulation and incentives to succeed. That is to say, once ratified, governments will formulate new regulations, incentives, and strategies to meet the SDGs, which will undoubtedly condition business activity.

Given that companies have been assigned this leading role in relation to the SDGs, the SE has emerged as the preferred means to this end. This economic area is made up of companies and entities whose operation is based on principles such as the prioritization of people over financial results, and democratic management, sharing values such as solidarity, and sustainability or commitment to the environment [

16]. These principles are present in all SE entities, both in market and non-market sectors [

2,

17]. These include a variety of organizations such as cooperatives, mutual societies, foundations, and associations, as well as new types of social enterprises. In generic terms, it refers to private entities created for social purposes, based on democratic and participatory governance [

10,

18]. This governance implies that participation is independent of each person’s individual participation in the company capital (one person, one vote). Affiliation to societies is open, and the surplus that is generated (if at all) cannot be appropriated by the agents who create, control or finance them [

18,

19].

We are, therefore, dealing with a group of companies and entities whose governance implies another way of generating economic activity, guided by different principles and priorities than those governing companies that prioritize profit maximization. Thus, the entities that make up the SE assume principles and values that enable development compatible with both economic and environmental aspects, that is, organizations with social and economic objectives that are not based solely on maximizing profit. In addition, the actors involved in the SE often live in the same territory where the activity takes place, thus allowing for an increased awareness of environmental issues. In sum, these entities have been shown to have social benefits. In their comprehensive review on SE outcomes, Chaves and Monzón [

20] highlighted among these results those from an economic approach such as correcting imbalances in the labor market, producing merit goods, local development and self-government, social cohesion, social innovation, democratizing the business function, and contributing to a fairer distribution of income and wealth.

In this regard, the UNTFSEE (2014) highlighted the importance of the social and solidarity economy in the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the achievement of the SDGs, in that it represents the plural economy, balance, sustainability and an integrated approach required to meet the challenge. It has also carried out several studies showing the links between these types of organizations and the SDGs. In particular, the position statement of the UN Inter-Agency Task Force on Social and Solidarity Economy, 2015 includes an extensive review of each of the SDGs, highlighting the relationship between these objectives and sub-objectives and the SE, and how it becomes a suitable vehicle to facilitate the SDGs.

In the academic field, however, there are still few studies exploring the relationship between the SE and the SDGs. In this context, it is worth mentioning Utting (2018), who insists on the need to establish effectiveness indicators for policies promoting the SE in terms of meeting the SDGs [

4]. Other studies have focused on the analysis of cooperative societies, underlining the importance of their principles and values as an exponent of socially responsible organizations [

21,

22,

23]. Although these studies predate the approval of the SDGs, their conclusions are equally relevant, given that they highlight the role of the cooperative enterprise as an entity closely aligned with these objectives [

24]. More recently, studies have presented extensive work that explores this alignment in depth, focusing on oil cooperatives in Andalusia [

25].

3. The Promotion of the Social Economy in Galicia

The institutional pronouncements, in favor of the importance of the SE for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda and achievement of the SDGs, recognize the importance of having an institutional and political context supportive of the SE in order to translate the commitment to this area of activity into a set of policies which, in turn, promote and encourage entities in this sector (Inter-Agency Task Force on Social and Solidarity Economy, 2015). Along these lines, many governments have adopted significant legal, political and institutional reforms in the last decade, aimed at enabling the growth of the SE.

In Spain, the legal framework in this sector is relatively recent: Law 5/2011 of 29 March, on the social economy (LSE). Furthermore, despite the importance of adaptation to specific socio-economic contexts, there is no specific regional legislation, except for the autonomous community of Galicia, with Law 6/2016 of 4 May, regarding the social economy in Galicia (LSEG). In fact, Galicia has been the first, and only, autonomous community to have its own SE regulations. Furthermore, there are various elements that distinguish the LSEG from the LSE and which should be described, given their relevance to local development. Thus, the LSEG includes two additional principles with respect to the LSE: commitment to the territory in the face of depopulation and aging in rural Galicia, and the strengthening of institutional and economic democracy through the SE [

9]. The first of these two principles requires a detailed explanation since it attempts to adapt the generic regulatory framework of the state to the socio-economic reality of Galicia; in addition, it becomes the axis of development for the entire regional text, presenting three distinct characteristics:

Consequently, the LSEG pays particular attention to two key elements for the development of the SE: attachment to the territory and the promotion of employment, aboth of which are vital for meeting two of the SDG goals, and the balanced distribution of wealth and the promotion of quality employment. This singularity and particular adaptation to the SDGs make the study of the Galician case particularly interesting; in recent years, a SE support and promotion system has been established which could lay the foundations for a paradigm shift in the shaping of a sustainable and communitarian system in order to meet the SDGs.

4. From an Ecosystem Conducive to the Social Economy to an Ecosystem that Fosters the Sustainable Development Goals

4.1. General Aspects

In this section, we will focus on identifying and valuing the relationship between SE entities in Galicia and the achievement of the SDGs in this autonomous community. Three reasons underlie the choice of this territorial area:

▪ Galicia is an autonomous community clearly differentiated in SE. As has been pointed out, it was the first autonomy to adopt its regulations in the field of the SE (LSEG), seeking to adapt and develop the guidelines contained in the LSE to the special characteristics of the Galician socio-economic context.

▪ The Galician community has a long tradition in policies of support and promotion of SE entities, mainly since 2012 with the creation of the Eusumo Network [

28].

▪ Galicia has high rates of an aging population, geographical dispersion, a hyper concentration of the population in the Atlantic Zone (particularly in large cities) and a high level of abandonment of rural areas. In addition, these elements can be extrapolated to other territories. Consequently, the results obtained by the Galician community may be of interest to other territorial areas that are undertaking the design of stimulus policies and, in general, for all those involved in the Agenda 2030 determined by the SDGs.

The autonomous community of Galicia has a long tradition of promoting the SE, in particular in promoting cooperatives. In this context, it should be noted that in recent years a triple helix ecosystem has been formed—legal, social and budgetary—which entails the creation of an optimal space for improving the competitiveness, job creation, and sustainability of the Galician SE [

28,

29,

30]. The triple helix ecosystem is comprised as follows:

▪ A legal ecosystem, since it has articulated a range of normative provisions, known as soft institutional policies [

8,

10,

18,

31] aimed at establishing a legal action framework for these entities, and at removing obstacles so that the entities comprising the SE can enter economic activity on an equal footing with other agents.

▪ A social ecosystem, with the creation of different consultative and advisory bodies and associations of representative entities, which should be understood as a way of recognizing the representational role of the organizations in the SE.

▪ A budgetary ecosystem, related to increased allocation in the general budgets of the autonomous community directed to the area of SE [

9,

29,

30]. As a demonstration of this reality, during the period 2008–2019, the SE promotion budget in Galicia has been growing at an average rate of 1.4% per year. Each of the steps taken by Galicia to consolidate the ecosystem favorable to the SE is reflected in these budgets. For example, with the approval of the LSEG in 2016, the budgets show an average annualized increase of 12.2%.

The formation of this triple ecosystem materializes in the design and implementation of the first Galician Social Economy Strategy (2019–2021), agreed with the sector, and addressed to the four SE families with the greatest potential for employment generation: cooperatives, labor societies, special employment centers, and employment enterprises. The joint analysis of the triple ecosystem for the promotion of the SE in Galicia and the resulting strategy explains the link between SE promotion in Galicia and the commitment to Agenda 2030 and the SDGs. All the measures are aimed at an explicit objective, the promotion of SE entities as a means of improving employability in Galicia.

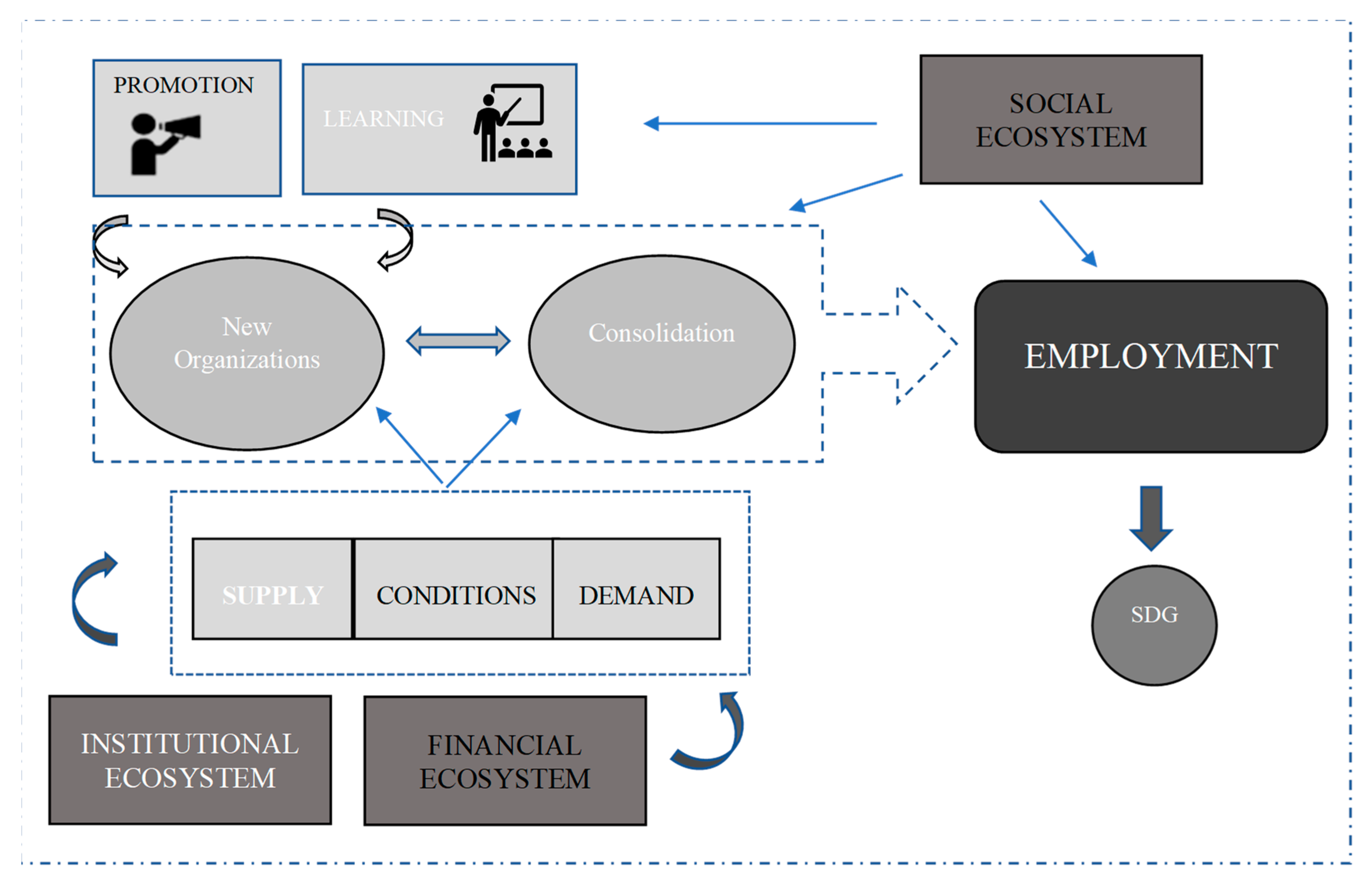

Figure 1 illustrates this relationship.

The actions carried out aim at improving the number of SE entities and their operating conditions in order to promote job creation; in turn, these jobs and their quality, the segments where employability increases the most and the places where it is located, all signal the progress made towards achieving the SDGs.

The three ecosystems defined above act as a lever for this system. Firstly, in the legal ecosystem, the conditions for the operation and financing of the activities of SE entities are established, identifying a series of actions aimed at improving the conditions and results of these entities, be they newly-created or already existing, and impacting their consolidation and viability. In this sense, it affects all segments of business activity, improving conditions—access to resources, new markets, improvements in size—and establishing a dynamic and flexible regulatory framework in order to adapt to changing conditions and to lay the foundations for better action.

Secondly, special attention is paid to the dissemination and knowledge of the SE, on the assumption that the higher the level of knowledge regarding the SE, the more likely it will be that entrepreneurs choose these forms of enterprise. At the same time, associations and relations between associations are encouraged with the aim of improving citizens’ perception of the SE (social economy).

Thirdly, all the actions are reflected in the general budgets of the autonomous community (financial ecosystem) and support for the implementation of explicit promotion measures and explicit incentives for the creation and consolidation of entities (for example, teaching or ICT-related entities) and in particular, its territorial decentralization (cooperative laboratories in rural areas). Regarding this point, it is necessary to analyze the explicit effort made by the regional administration in terms of budget allocation. In this respect,

Figure 2 summarizes the items intended for the promotion of the SE in Galicia between 2008 and 2019. As shown in the figure, it is evident that the Galician SE was affected by the cuts in the period of austerity following the economic crisis (2008–2011). This trend was interrupted by the creation of the Eusumo Network, in 2011–2012, leading to the largest budget allocation during the period analyzed, with more than 20.2 million euros in 2012. However, this stage was followed by a drastic reduction of more than 60% of the total amount in a single financial year. Fortunately, the approval of the LSEG in 2016 signaled a new expansive phase, acting as an accelerator of the budgetary allocations that have enabled the fiscal year 2019 to have the largest budget since the creation of the Eusumo Network, practically matching the 2012 funds. As a data of interest, it should be noted that the Galician’s draft budget for 2020 includes an amount of 27.0 million € to SE, an increase of 34.3% over the 2019 budget and the largest allocation on the period.

During this period, the SE promotion budget has been growing at an average rate of 1.4% per year. However, if we break down these years according to the milestones highlighted above, we see that growth in the period before the creation of the Eusumo Network (2008–2012) was 3.9%, accelerating significantly in the period after (2013–2016) to reach an annual average increase of 7.4%. After the approval of the LSEG in 2016, the budgets reflect an average increase in SE allocation of 12.2%. Even more, if we consider the allocation in the 2020 draft budget, the average allocation increases to slightly less to 90 %.

All in all, we are faced with a combination of soft and hard promotional policies in the classification, widely recognized in the academic field, of support for public policies promoting the SE [

10,

18,

31]. The former (soft policies) aim to establish a favorable ecosystem for the development of SE companies, which can be divided into institutional policies (focusing on establishing a legal structure for these entities, their full incorporation into economic activity, their representative role as social agents, and setting up a specific structure for the centralization of these activities) and cognitive policies, the aim of which is to foster knowledge, learning, and study of the SE.

As opposed to soft policies, hard policies are interventions directly oriented to the development of the economic activity of the SE entities (whether by influencing supply or demand). The Eusumo Network, managed by a specific division of the autonomous administration, has promoted the development of the LSEG and laid the foundations of the Consello Galego de Economía Social (soft institutional policies), and in its assessment has contributed mainly to the knowledge and dissemination of the SE in Galicia (soft cognitive). In addition, the measures of advice, mentoring, and those aimed at the establishment and consolidation of SE entities, place it within the framework of the development of what is considered hard policies of promotion.

All these actions are aimed at consolidating and increasing organizational efficiency and effectiveness, which is reflected in the increase in jobs linked to the sector. In addition, underlying coordination and resource sharing are improved, and actions specifically aimed at territorial redistribution (cooperative laboratories in rural areas, for example) are introduced. This has a direct impact on the SDGs most directly linked to economic activity, as will be discussed below.

4.2. The SDGs and the Social Economy

As noted in this paper, we will focus on the SDGs most closely related to the economic activity of the SE: achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls (SDG 5); promoting sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all (SDG 8); and contributing to the reduction of inequalities (SDG 10). Regarding gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls (SDG 5), it is articulated in two sub-goals:

▪ Ensure the full and effective participation of women and equal leadership opportunities at all decision-making levels in political, economic, and public life.

▪ Undertake reforms that give women equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to ownership and control of land and other goods, financial services, inheritance, and natural resources, in accordance with national laws.

Note that women particularly value mutual support, teamwork, and the bargaining power inherent in the cooperative formula, as opposed to other results [

32]. This premise coincides with previous studies which indicate that women’s priorities are more closely related to non-economic objectives such as work-life balance, with a special appreciation for the fact that the results of their work may feed back into groups with needs similar to their own [

33,

34]. These factors may explain why women are particularly committed to the values of the SE and have a certain willingness to work in cooperatives [

35,

36,

37]. A study focusing on Galicia, based on 264 female cooperative members [

28], demonstrated that women in Galicia recognized that the cooperative formula was particularly suited to the way in which they felt most comfortable working and that it supported the introduction of measures to improve work-life balance, leading to more equal opportunities between men and women.

Furthermore, the fact that the participants in SE entities are partners/owners leads to greater female empowerment than in other organizations [

38]. Consequently, this channel for women’s entrepreneurship in the SE context may be an effective way to address the high level of female unemployment [

5,

39,

40,

41]. Moreover, this objective is directly interrelated with the aforementioned objectives. Thus, although women are less organized and integrated into rural policies than men [

42], this female empowerment indirectly favors territorial structuring and the revitalization of rural areas [

43,

44,

45].

As regards to the relationship between the SE and territorial distribution and balance, citizens’ access to economic activity and service distribution on an equal basis is included in SDG 8 and SDG 10 (improvement of employment and profit distribution), specifically in two sub-objectives:

▪ Until 2030, to develop and implement policies promoting sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products. By 2020, efforts will have been made to substantially reduce the number of young people who are unemployed, not in education or untrained.

▪ To develop reliable, sustainable, resilient and quality infrastructures, including those of a regional and cross-border nature, so that economic development and human welfare are supported.

Various studies have shown that SE entities (most notably cooperatives) adapt to changes in their environment better than other types of organizations, due to the greater involvement of their members. This ensures a positive impact on territorial development through democratic governance, greater integration, and social cohesion [

46,

47,

48,

49]. In addition, by exercising the solidly traditional SE values and principles, SE activities do not tend to relocate, thus favoring the creation of employment and wealth in the areas in which they are located [

46]. It is common knowledge that SE entities are based on cooperation, trust, and democratic and solidary management among their partners, enhancing collective entrepreneurship which benefits the community in which it is developing, particularly in terms of sustainability [

21,

50].

Furthermore, not only does the acceptance of SE principles such as commitment to the community and cooperation favor its members, but it benefits the whole community in which the activity takes place [

51]. Through the development of these principles, SE entities take responsibility for and are concerned with the general interests of suppliers, customers, the employed and unemployed and citizenship in general. Likewise, SE entities are committed to respecting their surrounding environment while carrying out their economic activity [

5,

19,

51,

52].

In line with this principle, this territorial commitment is an engine for the use of local resources, thus enabling a knock-on effect for a local development strategy [

53]. Finally, in line with the principle of collaboration, thanks to the SE entities, networks of local, national, and transnational associations can be established; these have proven to be fundamental in creating a ripple effect in the pursuit of territorial balance [

53,

54].

Consequently, it would seem reasonable to expect the SE entities to have a positive effect on the territory’s economic creation, thus contributing to its development and with subsequent effects on SDG 8, with particular mention for the following; the effect of establishing cooperative laboratories in rural areas, the promotion of partnerships and the joint initiatives established with Portugal in the framework of the development and implementation of the Euro Region Galicia-Northern Portugal, as well as in the measures to promote cooperative self-employment among young people. As mentioned above, the LSEG explicitly supports the creation of youth cooperatives, seeking to facilitate the professional development of Galician youth. This cooperative specialty, limited to self-employment and joint exploitation of land, is restricted to those cooperatives mainly set up by young people between 16 and 29 years of age, the limit is being extended to 35 years in certain cases.

Finally, in regards to the relationship between the SE and quality employment, it should be noted that SDG 8 aims to achieve higher levels of economic productivity through diversification, technological modernization, and innovation, focusing on the most labor-intensive sectors with the most added value. To this end, two approaches are promoted:

▪ The implementation of development-oriented policies that support productive activities, the creation of quality jobs, entrepreneurship, creativity and innovation, and encourage the formalization and growth of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises, including access to financial services.

▪ By 2030, the substantial reduction of the proportion of young people who are not in employment, education or training.

Various studies have recognized the ability of the SEand cooperatives in particular, to respond to the effects of the economic crisis on employment and wage adjustment and to create quality employment with both direct and indirect effects on the working population [

5,

10,

18,

26,

55]. Unlike other types of companies, which in times of economic recession reduce their workforce in order to make a profit and/or minimize losses, SE entities prioritize the maintenance of jobs, even if this is at the expense of a reduction in potential job improvements and/or economic benefits. In addition, SE entities provide higher quality employment, greater job stability, greater flexibility to adapt based on adjustments in working time rather than in the workforce, and have a better survival rate, leading to employment indicators being maintained [

56,

57,

58].

It is worth pointing out that the SE contributes to the creation of stable, sustainable, and higher quality employment [

2], as well as creating new jobs and prioritizing the maintenance of existing ones in periods of crisis, and has been able to provide a pathway to employment for disadvantaged and socially excluded groups. In line with this research, the significant role in job creation attributed to the SE should be highlighted among the specific objectives stated in the LSEG. This driving role is widely supported in the regional regulations through a complete range of measures to promote and stimulate self-employment, cooperative entrepreneurship and business collaboration. In fact, the Law 5/1998 of 18 December 1998 on cooperatives in Galicia is being amended in order to impact the promotion of self-employment and improve the possibilities of raising financial resources for these entities of such high relevance in the SE.

5. Impact Assessment

In assessing the results of this support scheme, one should bear in mind that while only three years have passed since the implementation of LSEG, an initial analysis of its effects to ascertain its impact is still timely. To this end, we will focus on the study of cooperative societies, considered the heart of the SE [

10]. In addition, the particular importance of cooperative societies in addressing current challenges, such as socio-environmental protection or the contribution to employment generation for less-favored sectors, has been highlighted [

59] as this is equally aligned with the objectives of the 2030 Agenda.

In this context, the number of cooperative entities has been steadily increasing in recent years. As shown in

Figure 3, with the exception of a slight setback in 2016–2017, newly registered cooperatives have increased annually over the past decade. In particular, the number of new cooperatives registered in 2019 is three times higher than at the beginning of the decade.

An analysis of the location of Galician cooperatives reveals that they are present in 240 Galician municipalities (77% of the total number of municipalities in Galicia). There are seven large cities in the Galician community with more than 50,000 inhabitants, in whose area of influence 391 of the 1104 cooperatives active in 2019 are located. This indicates the potential for the redistribution of economic activity in this corporate formula, with 65% of activities located in rural areas (SDG 10).

As regards the number of direct jobs, as can be seen from

Table 2, cooperatives have generated almost 7500 jobs to members and employees (SDG8). In total, female cooperative members account for more than 37%. In this regard, according to official data disclosed by both the National Statistical Institute and the Galician Institute of Statistics (2018), the percentage of women in cooperatives is far higher than the presence of women in the decision-making bodies of IBEX35 companies (27%) and the percentage in managerial roles in Galician’s organizations (31%). Moreover, the gap between women’s cooperative entrepreneurship and its presence in other types of business initiatives is clearer, namely the ratio of creation of Galician companies founded exclusively by women or organizations where most of the founding persons are women (19.8%).

In this context, it should be noted that, in the years since the adoption of the LSEG, 81.6% of the cooperatives set up are based on worker cooperatives. The percentage of female members in these cooperatives is significantly higher than the average, with 53% in 2018. This allows us to infer the particular potential of cooperative societies for promoting women’s professional opportunities, facilitating their empowerment and contributing to equality (SDG 5).

Additionally, regarding the employment generation, it seems appropriate to analyze the result of a typology previously indicated in this work—youth cooperatives—for its potential contribution to entrepreneurship among the younger population sectors. Moreover, as mentioned above, this typology was authorized with the specific approval of the LSEG in 2016. Since that year, 15 such companies have been set up. Given that the period under analysis is so short (2016–2018), it is not possible to establish a clear trend in relation to the extent of its implementation. However, it can be said that 2018 was the year in which more youth cooperatives were registered, almost 50% of the total. This figure would lead us to be optimistic about the viability of this type of cooperative; moreover, they are included in worker cooperatives, community land cooperatives, and fishing resources cooperatives. Therefore, their potential contribution to economic activity distribution and the use of local resources should also be considered in the impact analysis (SDG 10).

In short, even when taking into account the caution needed when analyzing such a short period of time, it is clear that the foundations have been laid for the creation and running of an ecosystem that fosters the SE in Galicia. Continuing the progress of traditional policies supporting this area of the economy, the design of new promotion strategies has been further developed with the aim of generating synergistic effects.

What makes this system particularly interesting is the combination of new generation policies affecting different complementary aspects that come together to support the creation and consolidation of SE entities with the conviction that these entities not only create employment but stable, quality employment. In this way, efforts are made to raise awareness of the SE, so that these entities may become viable options in entrepreneurship.

In this sense, the effort made to promote the SE among young people is essential, so that they may consider these activities as a means of starting their careers. It is also worth mentioning the wide-ranging assistance available to those who wish to become partners with these entities, thus leading to greater commitment and involvement with the organizations. In addition, partnerships between SE entities are explicitly encouraged, with the aim of consolidating interest groups with greater bargaining power in the dialogue with other social actors. In this context, efforts to improve cross-border relations deserve particular attention, as they should contribute to increasing the size of these entities and the consolidation of multi-country groups with better competitive conditions.

The third form of aid is aimed at the relocation of economic activity, explicitly promoting its establishment throughout Galicia. As we have seen, cooperatives are located in rural areas; this undoubtedly represents a path for rapid economic regeneration which additionally builds on the use of local resources. Furthermore, one should not ignore the explicit support within this aid package for cooperative laboratories in rural areas as a means of promoting joint ventures.

The analysis of this aid package reveals how each of them aligns with the SDGs, in particular, those most closely linked to economic activity: reversing inequalities in and between territories (SDG 10), promoting quality employment (SDG 8), and promoting the equality and empowerment of women (SDG 5). The system is evidently subject to improvement; for example, among the strategies aimed at improving knowledge of SE entities, their introduction into university studies is a priority, as it can also contribute to improving the level of training and knowledge of these organizations. Among the actions aimed at equal opportunities, it would be advisable to introduce explicit policies for women to become partners, thus favoring their empowerment.

All in all, it would be premature to establish a causal relationship between the measures proposed by the LSEG and the results previously detailed. Even more, it might be also risky to link the public policies in the region and the accomplishment of the international agenda that constitutes the SDGs. Nevertheless, it should be noted that this ecosystem has proven to be be beneficial to SE, so it can be inferred that Galician’s government has been already working on the accomplishment of SDGs, even if not deliberately. Regarding this point, the European Commission (2016) noted that the participation of subnational governments favors the implementation of development strategies that are more closely linked to a specific context, and, therefore, to citizenship [

61,

62]. Additionally, this participation is also important in terms of monitoring the achievement of the SDGs, since regional governments are better suited to provide more precise information through the disaggregation of the available data and statistics. Monitoring this information is a crucial element in the context of the new sustainable development agenda. Taking into account these recommendations and the results of our study, Galician’s government has taken the first steps along a highly demanding path.

6. Conclusions

As can be seen, SDGs are a priority for all economic, institutional, and social actors, with a particular impact on the activities covered by the SE. This is because the principles of the SE include the need to achieve sustainable economic growth at a global level, a better future for future generations and, at the same time, to ensure a more equitable distribution of wealth in line with continued improvement in opportunities in life for all. The SE has an important role to play in achieving the UN SDGs, especially those most closely related to achieving sustained, inclusive and sustainable growth, achieving full employment and quality jobs for all.

In 2015, the UN established this series of SDGs to be met by 2030, guaranteeing active SE entities a leading role; hence, they have the responsibility of leading a wide range of initiatives, which, on the other hand, is already integral to the principles upon which the SE is based. As noted above, three SDGs are most relevant to the economic activity of the SE: achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls (SDG 5), fostering sustained economic growth, inclusive and sustainable, full and productive employment and decent work for all (SDG 8), and reducing inequalities in and between countries (SDG 10).

In recent years, and especially since the adoption of the LSEG, Galicia has witnessed a triple helix ecosystem—legal, social, and budgetary—which has enabled an optimal space to be created in order to improve competitiveness, job creation, and SE sustainability in Galicia. Preliminary results demonstrate the positive effects of this supportive ecosystem, particularly on cooperative entities. Thus, there is positive data regarding the creation of entities, jobs, territorial redistribution (particularly in rural areas), and figures for female participation. These results are particularly important in light of their explicit alignment with those SDGs most closely linked to economic activity.

Based on the relationship between the SE and the SDGs, the analysis of the development system designed in Galicia shows how institutions and governments can regulate this effect, accelerating its results and progressing towards meeting the Agenda 2030 commitments. This study represents a step closer to meeting these commitments, going beyond their traditional measurement in terms of environmental sustainability to place the focus on economic sustainability.

Furthermore, it may represent an investment in the current business vision. At the moment, the focus is on the inefficiencies and diseconomies resulting from this activity, which are responsible for generating significant differences between the territories and, therefore, between their inhabitants. However, the impetus and growth of a consolidated network of SE entities imply verifying how economic and business activity can achieve other types of results and, at the same time, helping to face other contemporary challenges such as depopulation, rural abandonment, unemployment and unequal opportunities for girls and women.

Finally, it would be premature to establish a causal relationship between the measures proposed by the LSEG and the results previously detailed. Regarding this point, some limitations should be noted. As has been previously noted, we have only three years to analyze the effects of the ecosystem deployed. Moreover, our data are descriptive, so our results might be due to serendipity. Additionally, there are barely any official data to make rigorous comparations between the evolution and location of SE entities, and more specifically, of cooperatives and other kinds of organizations. This limitation prevents us to make solid comparations to other groups of entities. In the same vein, it should be noted that we have explained a specific regional case, so we cannot generalize these preliminary outcomes. Consequently, more time and research are needed to address these caveats. In particular, future research should explore the autonomous community leaders’ discourses to analyze if the SDGs agenda is a real priority. It also might analyze the internal structure and functioning of cooperatives in order to further explore the connection between them and SDGs.

Summarizing, Galicia offers an example of good practice for developing the SE. The Galician community promotes a set of support and promotional policies with synergistic effects, consolidating a databank that can be extrapolated to other territories wishing to meet the challenge of implementing Agenda 2030 and making an explicit commitment to achieving the SDGs. The socio-economic conditions of the Galician community also offer the chance to investigate the SE’s ability to reverse the negative effects of an unprecedented demographic crisis, which in itself represents one of the most important challenges in this century.