4.1. Baseline Estimates—Equal Weights of Indicators

In the first stage of the empirical research, the level of smartness of housing markets in the studied cities was measured. This analysis was carried out in two stages: in the first stage, each dimension of the smart housing concept was evaluated separately; in the second stage, the comprehensive smart housing index was estimated on the basis of all dimensions of the investigated concept. The results of this study are presented in

Table 3.

Based on the results presented in

Table 3, it can be concluded that the smartest residential market is found in Cracow. This result is not surprising as Cracow is currently one of the fastest developing cities in Poland in terms of new jobs in innovative companies (BPO, SSC/GBS, IT, R & D), tourism or higher education. It is because of these features that Cracow is also ranked first in the “automatic” rental housing market dimension.

It should also be emphasised that housing developers are very active in the city of Cracow, which translates into the highest value, among the analysed cities, for innovative digital platforms in the traditional housing market. Unfortunately, the development of the real estate market through the construction of new dwellings by private developers may have contributed to stagnation in innovative housing policies offered by the city. In particular, there are currently no non-standard housing policies in Cracow that could increase both the availability and the affordability of housing. Conversely, the most innovative cities in the implementation of unconventional housing policies are Szczecin and Poznan, which translates into third and first place respectively in the innovative policies and housing models dimension. In particular, one should look at the housing programmes of the city of Szczecin, which uses so-called new housing models as part of their solutions on offer (see

Table A3). In the discussed dimension, the last position is held by the city of Bialystok, which is characterised by a lack of innovative housing policies, lack of co-living facilities and the lowest number of rooms to rent per 1000 residents (see

Table A4).

Looking at the level of the last dimension of the smart housing concept, i.e., ability to forecast demand on the housing market, it should be noted that the city of Gdansk has the highest value in this respect, and the city of Katowice the lowest. In this dimension, unexpectedly, the second place was taken by the city of Bydgoszcz, which in the remaining dimensions achieved results below the average.

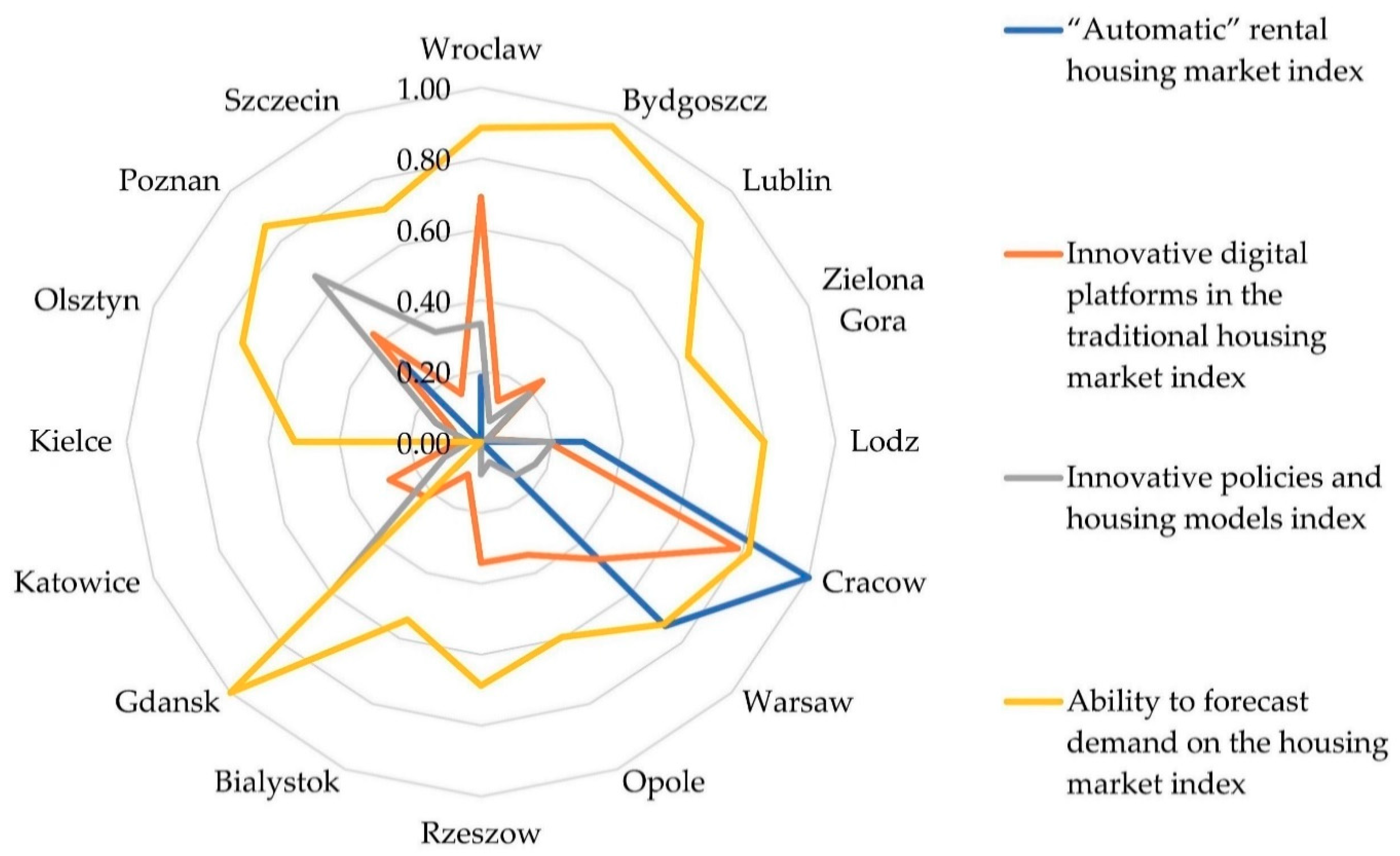

When analysing the estimates for all dimensions of the smart housing concept, it can be initially concluded that there is a great deal of variation among the cities in this respect. In particular, there are cities such as Cracow, Warsaw and Wroclaw, which demonstrate good results in almost every category of the smart housing concept. Conversely, cities such as Zielona Gora, Kielce or Bialystok have very bad estimates in each studied dimension. Unfortunately, the above conclusions are characteristic for Poland, where very large disparities between regions or cities can be observed. Within the smart housing concept, this diversification can be further intensified because it is a new, highly innovative concept; therefore, its development takes place especially in large urban centres. The above considerations are shown in

Figure 2 presenting the results achieved by the surveyed cities in terms of the four dimensions of the smart housing concept.

On the basis of

Figure 2, it can be stated that the smallest disproportions among the analysed cities concern the ability to forecast demand on the housing market dimension of the smart housing concept. This is not surprising, because in forecasting future demand for their products, local developers may use analyses of local entrepreneurs or scientists, or order them further afield. Therefore, it should be stated that this dimension of the smart housing concept has the most flexible character. This cannot be said of the other dimensions of the smart housing concept, which are inextricably linked to a given territory. This conclusion is also confirmed by

Figure 2, which shows that the other three dimensions of the smart housing concept behave very similarly, i.e., their values in different cities are not radically different. All this shows that the dimensions are closely linked and drive each other’s development.

In order to investigate further the differences in the Comprehensive Smart Housing Index, the cities in question were classified into four groups of similar objects (see

Table 4). This classification is another argument confirming the large disproportions in the smartness of the housing markets in Polish provincial cities. In particular, as many as 10 out of 16 cities are in the weak or average group, i.e., 62.5% of the analysed units. Then, the classification in

Table 4 is presented in

Figure 3 in order to check potential spatial dependencies. Through the results of this analysis, it can be cautiously concluded that, in general, the provincial cities in the western part of Poland have higher comprehensive smart housing index values than cities in the eastern part of the country (all cities in eastern Poland, i.e., Kielce, Olsztyn, Rzeszow, Lublin and Bialystok, are classified to the weak or average group).

In the next stage of this study, the correlations, between the comprehensive smart housing index and the factors that may drive the development of the smart housing concept as well as the potential positive effects of increasing the smartness of residential markets, were checked. The results of this analysis are presented in

Table 5. In the vast majority of cases, they confirm the conclusions drawn on the basis of theoretical considerations. In particular, there is a very strong correlation between the comprehensive smart housing index and the smart economy index, which positively verifies the conclusions presented in

Section 2.1 that, from the point of view of the smartness of the residential market, the development of the economic dimension of the smart city concept is crucial. In relation to the smart people dimension, a positive correlation with the analysed indicator can be observed, but it is insignificant, which makes any firm conclusions impossible. There is no correlation, however, between the smart governance index and the comprehensive smart housing index. This fact is not particularly surprising, as it may result from the specificity of the analysed cities. In particular, in Poland, the concept of governance is still being implemented. Despite the fact that in recent years a lot of progress has been made in this area, it should be emphasised that there is still a lot more to be done. This fact is indicated, among others, by the research conducted by Gross and Źróbek [

62], who assessed the level of good governance in public real estate management systems in Poland in comparison with other countries in Europe.

The ultimate factor potentially driving the development of housing market intelligence was the indicator concerning the implementation of the co-working concept in the studied cities. The estimated correlation proved to be important and is consistent with previous theoretical considerations. In Poland, however, it may result mainly from the fact that the smart residential market is much more flexible, which provides better service for equally flexible co-working spaces. Co-working facilities in Poland, however, do not offer the option of shared living or at least the possibility of building relationships among the people working in the same office [

63].

Next, the correlation between the comprehensive smart housing index and potential effects resulting from the increase in the smartness of residential markets in the analysed cities was assessed. The results of the study (see

Table 6) confirmed almost entirely previous theoretical considerations on this issue. In particular, the empirical research showed that an increase in the smartness of housing markets improves the quality of life of residents mainly in economic terms (salary increase, lower unemployment).

Additionally, the obtained results confirm that the increase in the smartness of the residential markets increases the availability of housing. This may result from the fact that in smart housing markets there is much higher prevalence of the concept of shared living, which in the context of Poland may lead to, among others, the carving out of new residential units, e.g., in single-family houses belonging to elderly people. The rise in housing availability may also result from the increasingly common practice of constructing buildings with a larger number of flats, characterised by smaller size.

It should also be noted that the smart housing market is also characterised by active government action in the area of housing. In this respect, the activities of local authorities in creating new real estate resources for different social groups will undoubtedly increase both the general availability of housing but also its affordability. As regards the latter, there is some feedback loop whereby the smart housing market enables people to adapt their place of residence to their place of work, allowing them to choose the most attractive employer. This in turn translates into higher wages, which may lead to an increase in a person’s housing purchasing power.

Moreover, on the basis of

Table 6 it can be seen that there is a negative correlation between the comprehensive smart housing index and the poverty index, which may indicate that the development of smart housing market in a given city also contributes to the reduction of poverty level. However, in this respect, the obtained correlation coefficient proved to be insignificant, which implies that this dependence should be analysed in subsequent studies.

4.2. Robustness Checks—Different Weights of Indicators

In order to control the results obtained in

Section 4.1, the calculation of the Comprehensive Smart Housing Index using different weights of indicators has been carried out. Moreover, weights were calculated for indicators concerning the following synthetic indexes: (1) smart people index; (2) smart economy index; (3) smart governance index; and (4) poverty index.

In addition, two options were used to estimate the smartness of the housing markets. The first was to calculate weights for all indicators presented in

Table 1. The second was to calculate weights for indexes synthetically describing each dimension of the smart housing concept (these indexes are presented in

Table 3). The calculated weights of indicators are shown in

Table 7. In particular, for the first option, the most important indicator was SH7, which describes the number of typical co-living facilities in a city. However, looking at the second option, the index describing the “automatic” rental housing market dimension of the smart housing concept proved to be crucial.

Estimates using different weights of indicators are almost entirely consistent with these presented in

Section 4.1 (see

Table 8). In particular, the housing markets in cities such as Cracow, Warsaw, Poznan, Wroclaw and Gdansk are still characterised by the highest levels of smartness. The biggest change in this respect concerns the city of Gdansk, which results from the fact that in this city there is the only functioning co-living facility in Poland [

64]. Therefore, in the case of weighting of each indicator from

Table 1, Gdansk’s position in the final ranking is artificially inflated; hence, two different weighting estimation procedures were applied when calculating the comprehensive smart housing index.

Moreover, when analysing

Table 9 and

Table 10, a similar consistency in the scope of potential driving forces and effects of the smart housing concept can also be observed (compare

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 9 and

Table 10). The only difference concerns potential driving forces of the smart housing concept. In particular, there is little support for the conclusion that the development of the city in terms of smart people also contributes to the growth of the smartness of the housing market. However, this dependence is only significant in one case; hence, it should be the subject of future research.