South American Expert Roundtable: Increasing Adaptive Governance Capacity for Coping with Unintended Side Effects of Digital Transformation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Contextualizing Digital Transformation in Developing and Transitioning Countries

1.2. Adaptive Governance Capacity for Developing Socio-Technical Innovation

- (i)

- a laissez-faire, industry-driven approach; an open-market-based approach that relies on a market’s ability to organize and protect itself in the face of threats; and limited government intervention;

- (ii)

- a precautionary and preemptive strategy on the part of a government to avoid or prevent exposure to irreversible threat and mitigate risk in the immediate future; and

- (iii)

- a stewardship and “active surveillance” approach by government agencies to reduce risks derived from digitalization while promoting private-sector innovation.

1.3. Goals of the South American ERT (Proposition-Based)

2. Theory

2.1. Mechanisms on Unseens

2.2. Impacts of Digital Transformation and Innovations in Economy and Society

2.3. Science–Practice Collaboration and the Vision of a Transdisciplinary Process Following the Legal Aspects of How a Particular Solution will be Adopted and How Users will Benefit from It

3. Methodology

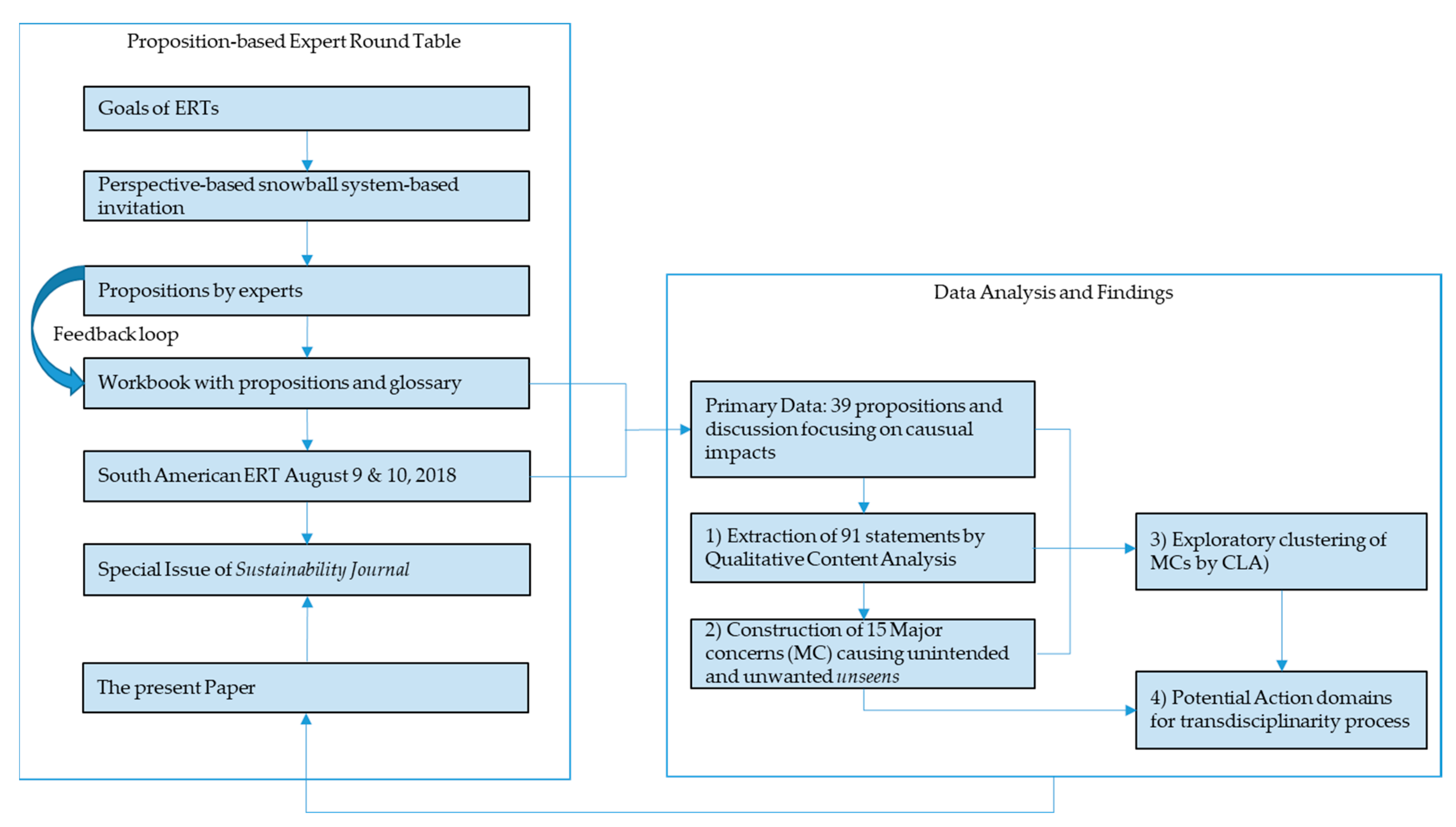

3.1. The Methodology of Proposition-Based Expert Roundtables

3.2. Data Analysis: A New Form of Clustering the Mechanisms of Unseens

4. Results

4.1. Drivers and Challenges/Barriers Identified in the Proposals of South American Experts

4.2. Unseens Discussed in the South American ERT and Main Groups of Causalities Resulting in Unintended and Unwanted Unseens

- Ref. 1: Towards Homo Digitalis: Important Research Issues for Psychology and the Neurosciences at the Dawn of the Internet of Things and the Digital Society. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/10/2/415 (accessed on 10 November 2019).

- Ref. 2: President’s Memorandum on Transparency and Open Government - InteragencyCollaboration. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/memoranda/2009/m09-12.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2019).

- Ref. 3: Corruption Perceptions Index 2018. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/cpi2018 (accessed on 10 November 2019).

- Ref. 4: Americas: weakening democracy and rise in populism hinder anti-corruption efforts. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/cpi-2018-regional-analysis-americas (accessed on 10 November 2019).

- Ref. 5: Unlocking the potential of SMEs for the SDGs. Available online: https://oecd-development-matters.org/2017/04/03/unlocking-the-potential-of-smes-for-the-sdgs/ (accessed on 10 November 2019).

4.3. Cluster Analysis

4.4. Initiating a Transdisciplinary Follow up Process in Brazil

5. Discussion

5.1. Methodology of Problem Structuring by Proposition-Based ERTs

5.2. Scientific Outcomes for Understanding the Systems

5.2.1. Aspects Related to Individual Behavior

5.2.2. The Role of Governmental Organizations

5.2.3. Societies

5.2.4. The Sociotechnical Systems

5.3. Brazilian Case Study for Transdisciplinary Processes and Reorganizing Science

5.4. Strengths and Limits of the Presented Method

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Propositions on the Future Perspectives on Digital Transition

Appendix A.1. Propositions on Digital Infrastructure: New Governance Models for Sustainable Development: Elsa Estevez

Appendix A.2. Propositions on Artificial Intelligence: Social Impacts of Algorithmic-Based Recommendations: Carlos Chesñevar

Appendix A.3. Propositions on the Dark Side of ICT: Luiz Antonio Joia

Appendix A.4. Propositions on the Rebounds of Smart Cities: Maria Alexandra Cunha and João Porto de Albuquerque

Appendix A.5. Propositions on Economic Change: Carlos O. Quandt, Alex Antonio Ferraresi and Eduardo Damião da Silva

Appendix A.6. Propositions on Industrial Change: Pablo Collazzo-Yelpo

Appendix A.7. Propositions on Big Data in Occupational Health: Frida Marina Fischer, João Silvestre Silva-Junior, Maria Carmen Martinez, Rodolfo Andrade de Gouveia Vilela, Luis Fabiano de Assis, Maria Regina Alves Cardoso

Appendix A.8. Propositions on Digital Democracy: Diego Cardona and Aurora Sánchez

Appendix A.9. Propositions on Cybercrime: Rodrigo Sánchez Rios

Appendix A.10. Propositions on Corruption: Edimara M. Luciano

Appendix A.11. Propositions on Banking and Cryptocurrency: Eduardo Henrique Diniz

References

- Linkov, I.; Trump, B.; Poinsatte-Jones, K.; Florin, M.V. Governance strategies for a sustainable digital world. Sustainability 2018, 10, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scholz, R.W.; Bartelsman, E.J.; Diefenbach, S.; Franke, L.; Grunwald, A.; Helbing, D.; Hill, R.; Hilty, L.; Höjer, M.; Klauser, S.; et al. Unintended side effects of the digital transition: European scientists’ messages from a proposition-based expert round table. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loebbecke, C.; Picot, A. Reflections on societal and business model transformation arising from digitization and big data analytics: A research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuvelink, G.B.M. Error Propagation in Environmental Modelling with GIS; CRC Press: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Junkins, J.L.; Akella, M.R.; Alfriend, K.T. Non-Gaussian error propagation in orbital mechanics. Adv. Astronaut. Sci. 1996, 92, 283–298. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Tan, X.; He, D.; Tian, F.; Qin, T.; Lai, J.H.; Liu, T.Y. Beyond error propagation in neural machine translation: Characteristics of language also matter. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1809.00120. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama, M.; Deguchi, H.; Ema, A.; Kishimoto, A.; Mori, J.; Shiroyama, H.; Scholz, R.Z. Unintended side effects of digital transition: Perspectives of Japanese Experts. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scholz, R.W.; Viale-Pereira, G. Workbook for Preparing the South American Round Table Structuring Research on Sustainable Digital Environments Curitiba, August 9–10, 2018. Logistics - Schedule - Focus, Goals, Products - Rules of Discussion - Propositions- Glossary – Participants; Danube University of Krems: Krems, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N.; Brooks, N.; Bentham, G.; Agnew, M.; Eriksen, S. New Indicators of Vulnerability and Adaptive Capacity; University of East Anglia; NorwichTyndall Centre for Climate Change Research Norwich: Norwich, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, R.W.; Blumer, Y.B.; Brand, F.S. Risk, vulnerability, robustness, and resilience from a decision-theoretic perspective. J. Risk Res. 2012, 15, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattberg, P.; Widerberg, O. Transnational multistakeholder partnerships for sustainable development: Conditions for success. Ambio 2016, 45, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Padmanabhan, M. (Ed.) Introduction: Transdisciplinarity for Sustainability, in Transdisciplinary Research and Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, R.W.; Kley, M.; Parycek, P. Reframing Global and European Digital Infrastructure as a Public Good!? Department of Knowledge and Information Management, Danube University Krems: Krems an der Donau, Austria, 2020; Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, R.W.; Steiner, G. The real type and ideal type of transdisciplinary processes: Part I—Theoretical foundations. Sustain. Sci. 2015, 10, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, R.W. Environmental Literacy in Science and Society: From Knowledge to Decisions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C. Double Loop Learning in Organizations. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1977, 55, 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, J.W. Principles of Systems: Text and Workbook; Wright-Allen-Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Helbing, D.; Frey, B.S.; Gigerenzer, G.; Hafen, E.; Hagner, M.; Hofstetter, Y.; Hoven, J.V.D.; Zicari, R.V.; Zwitter, A. Will Democracy Survive Big Data and Artificial Intelligence. Sci. Am. 2017, 25. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/will-democracy-survive-big-data-and-artificial-intelligence/ (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Zuboff, S. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for the Future at the New Frontier of Power; Profile Books: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Helbing, D. The Automatization of Society is Next; Great Britain (Amazon): Dirk Helbing; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hobart, M.E.; Schiffman, Z.S. Information Ages: Literacy, Numeracy, and the Computer Revolution; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Berners-Lee, T.; Fischetti, M. Weaving the Web: The Original Design and Ultimate Destiny of the World Wide Web by its Inventor; DIANE Publishing Company: Darby, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Heylighen, F.; Lenartowicz, M. The Global Brain as a model of the future information society: An introduction to the special issue. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 114, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xu, L.D.; Zhao, S. 5G Internet of Things: A survey. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2018, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moy, P.; Hussain, M.M. Media and Public Opinion in a Fragmented Society, in the Spiral of Silence; Donsbach, W., Salmon, C.T., Tsfati, Y., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, C.B.; Osborne, M. The Future of Employment. How Susceptible are Jobs to Computerisation; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Krausmann, F.; Gingrich, S.; Eisenmenger, N.; Erb, K.H.; Haberl, H.; Fischer-Kowalski, M. Growth in global materials use, GDP and population during the 20th century. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 2696–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; Vries, W.D.; Wit, C.A.D. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Velik, R. Quo Vadis, intelligent machine? BRAIN. Broad Res. Artif. Intell. Neurosci. 2010, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Vanparijs, P. Why surfers should be fed—The liberal case for an unconditional basic income. Philos. Public Aff. 1991, 20, 101–131. [Google Scholar]

- Bidadanure, J.U. The political theory of universal basic income. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2019, 22, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahay, S.; Sein, M.K.; Urquhart, C. Flipping the context: ICT4D, the next grand challenge for IS research and practice. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2017, 18, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, R.W.; Le, Q.L. Sustainable Phosphorus Management: A Global Transdisciplinary Roadmap; Scholz, R.W., Roy, A.H., Brand, F.S., Hellums, D.T., Ulrich, A.E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 116–118. [Google Scholar]

- Mingers, J.; Rosenhead, J. Problem structuring methods in action. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 152, 530–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, C.; Ackermann, F. Where next for problem structuring methods. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2006, 57, 766–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenhead, J. Past, present and future of problem structuring methods. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2006, 57, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, G.; Cavana, R.Y.; Brocklesby, J.; Foote, J.L.; Wood, D.R.R.; Ahuriri-Driscoll, A. Towards a new framework for evaluating systemic problem structuring methods. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013, 229, 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, R.W.; Spoerri, A.; Lang, D.J. Problem structuring for transitions: The case of Swiss waste management. Futures 2009, 41, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, R.W.; Czichos, R.; Parycek, P.; Lampoltshammer, T.J. Organizational vulnerability of digital threats: A first validation of an assessment method. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 282, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O.; Scholz, R.W. The Unintended Side Effects of Digitalization. DiDaT: The Responsible of Use Digital Data as the Focus of a New Transdisciplinary Project; IASS: Potsdam, Germay, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellman, R. Artificial Intelligence: Can Computers Think; Thomson Course Technology: Boston, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Merten, K. Inhaltsanalyse: Einführung in Theorie, Methode und Praxis; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Walsham, G. ICT4D research: Reflections on history and future agenda. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2017, 23, 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montag, C.; Diefenbach, S. Towards Homo Digitalis: Important Research Issues for Psychology and the Neurosciences at the Dawn of the Internet of Things and the Digital Society. Sustainability 2018, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bennett, W.L.; Segerberg, A. The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2012, 15, 739–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Melo, F.L.N.B.D.; Sampaio, L.M.B.; Oliveira, R.L.D. Bureaucratic Corruption and Entrepreneurship: An. Empirical Analysis of Brazilian States. Rev. Adm. Contemp. 2015, 19, 374–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luciano, E.M.; Scholz, R.W. The Unintended Side Effects of Digitalization. MitiCo: Mitigating Corruption in Brazil through a Transdisciplinaty Analysis; PUCRS: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenhead, J.; Mingers, J. Rational Analysis for a Problematic World Revisited; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, R.W.; Steiner, G. Transdisciplinarity at the crossroads. Sustain. Sci. 2015, 10, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pereira, G.V.; Parycek, P.; Falco, E.; Kleinhans, R. Smart governance in the context of smart cities: A literature review. Inf. Polity 2018, 23, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ITU. ITU Releases 2018 Global and Regional ICT Estimates. 2018. Available online: https://www.itu.int/en/mediacentre/Pages/2018-PR40.aspx (accessed on 27 November 2019).

- ITU. Measuring the Information Society Report 2017; International Telecommunication Union (ITU): Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bertot, J.C.; Estevez, E.; Janowski, T. Universal and contextualized public services: Digital public service innovation framework. Gov. Inf. Q. 2016, 33, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryznar, M. Protecting Users of Social Media. Notre Dame Law Rev. Online, Notre Dame 2019. Available online: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1067&context=ndlr_online (accessed on 27 November 2019).

- Gurstein, M.B. Open data: Empowering the empowered or effective data use for everyone? First Monday 2011, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufekci, Z. Social movements and governments in the digital age: Evaluating a complex landscape. J. Int. Aff. 2014, 68, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Matz, S.; Rolnik, G.; Cerf, M. Solutions to the Threats of Digital Monopolies. In Digital Platforms and Concentration; ProMarket: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Luca, M.; Wu, T.; Couvidat, S.; Frank, D.; Seltzer, W. Does Google Content Degrade Google Search? Experimental Evidence; Working Paper 16-035; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Filippi, P.D.; Vieira, M.S. The Commodification of Information Commons: The case of cloud computing. Technol. Law Rev. 2014, 16, 102–143. [Google Scholar]

- UN ECLAC. Estado de la Banda Ancha en América Latina y el Caribe 2016; United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean: Santiago, Chile, 2016; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, C.; Botti, V.; Ossowski, S. Agreement Computing. KI Künstliche Intell. 2011, 25, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesñevar, C.; Onaindia, E.; Ossowski, S.; Vouros, G. (Eds.) Special issue on agreement technologies. Inf. Syst. Front. 2015, 17, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chesñevar, C.; Maguitman, A.; González, M. Empowering recommendation technologies through argumentation. In Argumentation in Artificial Intelligence Chapter 20; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 403–422. [Google Scholar]

- Anandhan, A.; Shuib, L.; Ismail, M.A.; Mujtaba, G. Social Media Recommender Systems: Review and Open Research Issues. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 15608–15628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras, S.; Palanca, J.; Chesñevar, C. Argumentation-based Personal Assistants for Ambient Assisted Living. In Personal Assistants: Emerging Computational Technologies; Costa, A., Julian, V., Novais, P., Eds.; Intelligent Systems Reference Library; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018; Volume 132, pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, M.; Al-Fuqaha, A. Enabling Cognitive Smart Cities Using Big Data and Machine Learning: Approaches and Challenges. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vishwanath, R.; Hulipalled, R.; Venugopal, K.; Patnaik, L. Consumer insight mining: Aspect based Twitter opinion mining of mobile phone reviews. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 68, 765–773. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Shen, Z.; Miao, C.; Leung, C.; Lesser, V.; Yang, Q. Building Ethics into Artificial Intelligence. IJCAI 2018, 5527–5533. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, K. The moral challenges of driverless cars. Commun. ACM 2015, 58, 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, P.; Meadows, B.; Sridharan, M.; Choi, D. Explainable Agency for Intelligent Autonomous Systems; IAAI: Westchester, IL, USA, 2017; pp. 4762–4763. [Google Scholar]

- Avgerou, C.; Walsham, G. Introduction: IT in developing countries. Inf. Technol. Context Stud. Perspect. Dev. Ctries. 2000, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Avgerou, C. The link between ICT and economic growth in the discourse of development. In Organizational Information Systems in the Context of Globalization; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 373–386. [Google Scholar]

- Macadar, M.A.; Reinhard, N. Telecentros comunitários possibilitando a inclusão digital: Um estudo de caso comparativo de iniciativas brasileiras. Anais do 26 ENANPAD. 2002. Available online: http://www.anpad.org.br/admin/pdf/enanpad2002-adi-1296.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Silva, L.; Figueroa, B.E. Institutional intervention and the expansion of ICTs in Latin America: The case of Chile. Inf. Technol. People 2002, 15, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joia, L.A.; Zamot, F. Internet-Based Reverse Auctions by the Brazilian Government. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries 2002, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galperin, H.; Mariscal, J. (Eds.) Digital Poverty: Latin American and Caribbean Perspectives; IDRC: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, R.P.; Joia, L.A. Agência Barco e a Inclusão Ffinanceira da População Ribeirinha da Ilha de Marajó. e populações ribeirinhas: Avaliação de impacto da Agência Barco. Rev. Adm. Pública 2017, 52, 650–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, G.R. Information and Communication Technologies and Non-Governmental Organisations: Lessons Learnt from Networking in Mexico. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries 2005, 21, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton Studies in Culture/Power/History; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A.K. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Joia, L.A. Bridging the digital divide: Some initiatives in Brazil. Electron. Gov. Int. J. 2004, 1, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.A. Internet e mobilização política: Os movimentos sociais na era digital. Encontro Compolítica 2011, 4, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. Communication Power; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lugão, A.C.; Santana, E.; Ferrari, M.; de Jesus, D.S.V. Conselho europeu: Austeridade, estabilidade e crescimento–Novos acordos em tempos de crise. Modelo Intercolegial de Relações Internacionais. 2014. Available online: http://ptdocz.com/doc/190832/conselho-europeu--austeridade (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Ramos, A.; Oliveira, R. Indivíduos, sociedade, tecnologia: As manifestações nas ruas das cidades brasileiras e as redes sociais. Rev. Tecnol. Soc. 2014, 10, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joia, L.A. Social Media and the “20 Cents Movement” in Brazil: What Lessons Can Be Learnt from This? Inf. Technol. Dev. 2016, 22, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. A Galáxia Internet: Reflexões Sobre a Internet, Negócios e a Sociedade; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Passini, S. The facebook and Twitter revolutions: Active participation in the 21st century. Hum. Aff. 2012, 22, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirky, C. The political power of social media: Technology, the public sphere, and political change. Foreign Aff. 2011, 90, 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Papic, M.; Noonan, S. Social media as a tool for protest. Stratf. Glob. Intell. 2011, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, M.S.; Yeum, D.S. The impact of mobile technology paradox perception and personal risk-taking behaviors on mobile technology adoption. Manag. Sci. Financ. Eng. 2010, 16, 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Archer, N.; Connelly, C.E.; Zheng, W. Identifying the ideal fit between mobile work and mobile work support. Inf. Manag. 2010, 47, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulasvirta, A.; Rattenbury, T.; Ma, L.; Raita, E. Habits make smartphone use more pervasive. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2012, 16, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.P.; Joia, L.A. Executives and smartphones: An ambiguous relationship. Manag. Res. Rev. 2013, 36, 1167–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.P.; Joia, L.A. Paradoxes perception and smartphone use by Brazilian executives: Is this genderless? J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2015, 26, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barjis, J.; Gupta, A.; Sharda, R. Knowledge work and communication challenges in networked enterprises. Inf. Syst. Front. 2011, 13, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clegg, S.R.; da Cunha, J.V.; Cunha, M.P. Management paradoxes: A relational view. Hum. Relat. 2002, 55, 483–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mick, D.G.; Fournier, S. Paradoxes of technology: Consumer cognizance, emotions, and coping strategies. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 25, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudry, A.; Pinsonneault, A. Understanding user responses to information technology: A coping model of user adaptation. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 493–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolívar, M.P.R. Characterizing the role of governments in smart cities: A literature review. In Smarter as the New Urban; Gil-Garcia, J.R., Pardo, T.A., Nam, T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 49–71. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz, E.H.; Barbosa, A.F.; Junqueira, A.R.B.; Prado, O. O governo eletrônico no Brasil: Perspectiva histórica a partir de um modelo estruturado de análise. Rev. Adm. Pública 2009, 43, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cunha, M.A.; Miranda, P.D.M. A pesquisa no uso e implicações sociais das tecnologias da informação e comunicação pelos governos no Brasil: Uma proposta de Agenda a partir de reflexões da prática e da produção acadêmica nacional. O&S–Organizações & Sociedade 2008, 66, 543–566. [Google Scholar]

- CGI, Comitê Gestor da Internet no Brasil. Pesquisa Sobre o uso de Tecnologias de Informação e Comunicação no Brasil, TIC Governo Eletrônico 2017; Comitê Gestor da Internet no Brasil: São Paulo, Brasil, 2018.

- Przeybilovicz, E.; Cunha, M.A.; Meirelles, F. The use of information and communication technology to characterize municipalities: Who they are and what they need to develop e-government and smart city initiatives. Braz. J. Public Adm. 2018, 52, 630–649. [Google Scholar]

- Angelidou, M. Smart city policies: A spatial approach. Cities 2014, 41, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, R. Aspects of change. In The Gentrification Debates A Reader; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 1964; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N. New globalism, new urbanism: Gentrification as global urban strategy. Antipode 2002, 34, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, J.P.D.; Almeida, A.A.D. Modes of engagement: Constitutive tensions in citizen sensing and volunteered geographic information. In Mah et al. (Forthcoming), Environmental Justice and Citizen Science in a Post Truth Age; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Urbanization and Development: Emerging Futures. In World Cities Report 2016; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, A.M. Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chui, M.; Lund, S.; Madgavkar, A.; Mischke, J.; Ramaswamy, S. Smart Cities: Digital Solutions for a More Livable Future; McKinsey&Company: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mah, A. Environmental justice in the age of big data: Challenging toxic blind spots of voice, speed, and expertise. Environ. Sociol. 2017, 3, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haklay, M. Neogeography and the delusion of democratisation. Environ. Plan. A 2013, 45, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourish, P. The Internet of Urban Things. In Code and the City; Kitchin, R., Perng, Y.S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrys, J. Program Earth—Environmental Sensing Technology. Minneapolis; University of Minnesota Press: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, C. Plotting practices and politics: (im)mutable narratives in OpenStreetMap. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2014, 39, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, C.B.; Osborne, M.A. Technology at Work v2.0: The future is not what it used to be. CITI GPS Global Perspectives & Solutions, 26 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- De Groen, W.P.; Lenaerts, K.; Bosc, R.; Paquier, F. Impact of Digitalisation and the on-Demand Economy on Labour Markets and the Consequences for Employment and Industrial Relations. Final Study. CEPS Special Report, August 2017. Policy Paper. Available online: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/resources/docs/qe-02-17-763-en-n.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Hüsing, T.; Korte, W.B.; Dashja, E. E-Skills & Digital Leadership Skills Labour Market in Europe 2015–2020. empirica Schriftenreihe Nr 2/2016. 2016. Available online: https://epale.ec.europa.eu/en/resource-centre/content/e-skills-europe-trends-and-forecasts-european-ict-professional-and-digital (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Rodrik, D. Premature Deindustrialization. National Bureau of Economic Research, No. w20935. 2015. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w20935 (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Jerome, J. Buying and Selling Privacy: Big Data’s Different Burdens and Benefits. Stanford Law. 2013. Available online: https://www.stanfordlawreview.org/online/privacy-and-big-data-buying-and-selling-privacy/ (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Katz, R. Social and Economic Impact of Digital Transformation on the Economy; GSR-17 Discussion Paper; ITU: Pairs, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D. The Opportunities and Risks of the Sharing Economy; Testimony before the Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade of the US House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kergroach, S. Industry 4.0: New Challenges and Opportunities for the Labour Market. Foresight STI Gov. 2017, 11, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage of Nations. Harvard Bus. Rev. 1990, 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Assis, L.F.; Fujiwara, L.; Vilela, R.A.G.; Cardoso, M.R.A. Observatório Digital de Saúde e Segurança do Trabalho (MPT-OIT). In Dicionário de saúde e segurança do trabalhador: Conceitos, definições, história, cultura; Mendes, R., Ed.; Proteção Publicações Ltda: Novo Hamburgo, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Fazenda, Secretaria de Previdência, Empresa de Tecnologia e Informações da Previdência. Anuário Estatístico da Previdência Social—Ano 2016. Brasília: MF/DATAPREV; 2017. Available online: http://sa.previdencia.gov.br/site/2018/08/aeps2016.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Ilmarinen, J. Towards a Longer Worklife! Ageing and the Quality of Worklife in the European Union; Finnish Institute of Occupational Health: Helsinki, Finnish, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Morschhäuser, M.; Sochert, R. Healthy Work in an Ageing Europe: Strategies and Instruments for Prolonging Working Life. European Network for Workplace Health Promotion. 2008. Available online: http://www.ageingatwork.eu/resources/health-work-in-an-ageing-europe-enwhp-3.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Brasil. Lei nº 13.467, de 13 de julho de 2017. Altera a Consolidação das Leis do Trabalho (CLT), aprovada pelo Decreto-Lei no 5.452, de 1o de maio de 1943, e as Leis nos 6.019, de 3 de janeiro de 1974, 8.036, de 11 de maio de 1990, e 8.212, de 24 de julho de 1991, a fim de adequar a legislação às novas relações de trabalho. Diário Oficial da União. 14 jul 2017. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2017/lei/l13467.htm (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Brasil. Câmara dos Deputados. Comissão de Constituição e Justiça e de Cidadania (CCJC). Proposta de Emenda à Constituição 287, de 08 de dezembro de 2016. Altera os arts. 37, 40, 109, 149, 167, 195, 201 e 203 da Constituição, para dispor sobre a seguridade social, estabelece regras de transição e dá outras providências. Available online: http://www.camara.gov.br/proposicoesWeb/prop_mostrarintegra?codteor=1514975&filename=PEC+287/2016 (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Brasil. Decreto no. 8373, de 11 de dezembro de 2014. Institui o Sistema de Escrituração Digital das Obrigações Fiscais, Previdenciárias e Trabalhistas - eSocial e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União. 12 dez 2014. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2014/decreto/d8373.htm (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Cardona, D.; Serida-Nishimura, J. The Peruvian Citizen Perception and Expectation toward the e–government. The Electronic Tax Payment as a Successful e–Gov Project; Revista Universidad y Empresa, Facultad de Administración Universidad del Rosario: Bogota, Colombia, 2006; Volume 8, pp. 142–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona, D.; López-Bachiller, J.; Saenz-Core, J. ICT for development and the MuNet program: Experiences and lessons learnt from an indigenous municipality in Guatemala. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, Macao, China, 10–13 December 2012; pp. 188–191, ISBN 978-1-4503-1200-4. Available online: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2463728.2463767 (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Treré, E. The Dark Side of Digital Politics: Understanding the Algorithmic Manufacturing of Consent and the Hindering of Online Dissidence. Open. Govern. 2016, 47, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, M.-H.; Hong, W. Digital Revolution or Digital Dominance? Regime Type, Internet Control, and Political Activism in East Asia. Korean J. Int. Stud. 2017, 15, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jost, J.T.; Barberá, P.; Bonneau, R.; Langer, M.; Metzger, M.; Nagler, J.; Sterling, J.; Tucker, J.A. How Social Media Facilitates Political Protest: Information, Motivation, and Social Networks. Political Psychol. 2018, 39, 85–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sunstein, C.R. #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Krämer, B. Populist online practices: The function of the Internet in right-wing populism. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 1293–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, D.; Cortés, J.; Ujueta, S. Gobierno Electrónico en Colombia: Marco normativo y evaluación de tres índices estratégicos. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 2015, No. 20 (January-March). Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=29036968002 (accessed on 25 July 2018).

- Carr, I.; Jago, R. Petty Corruption, Development and Information Technology as an Antidote. Round Table 2014, 103, 465–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gauld, R.; Goldfinch, S.; Horsburgh, S. Do they want it? Do they use it? The ‘Demand-Side’ of e-Government in Australia and New Zealand. Gov. Inf. Q. 2010, 27, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Business model innovation: It’s not just about technology anymore. Strat. Leadersh. 2007, 35, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nfuka, E.; Rusu, L.; Johannesson, P.; Mutagahywa, B. The State of IT Governance in Organizations from the Public Sector in a Developing Country. In Proceedings of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) 2009 42nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2009; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, K.; Forgues-Puccio, G.F. Why is corruption less harmful in some countries than in others? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2009, 72, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dreher, A.; Gassebner, M. Greasing the wheels? The impact of regulations and corruption on firm entry. Public Choice 2013, 155, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Bank Group. Ease of Doing Business Ranking. 2018. Available online: http://www.doingbusiness.org (accessed on 9 April 2018).

- Transparency International. Corruption Perception Index. 2017. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/ (accessed on 3 March 2018).

- Holmemo, M.D.Q.; Ingvaldsen, J.A. Local adaption and central confusion: Decentralized strategies for public service Lean implementation. Public Money Manag. 2018, 38, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Monte, A.; Papagni, E. Public expenditure, corruption, and economic growth: The case of Italy. Eur. J. Politi Econ. 2001, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Power, T.J.; González, J. Cultura política, capital social e percepções sobre corrupção: Uma investigação quantitativa em nível mundial. Rev. Sociol. Política 2003, 21, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carraro, A.; Menezes, G.R.; Canever, M.D.; Fernandez, R.N. Formação de Empresas e Corrupção: Uma Análise para os Estados Brasileiros; Encontro de Economia da Região Sul - ANPEC/SUL: Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brasil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bertot, J.C.; Jaeger, P.T.; Grimes, J.M. Using ICTs to create a culture of transparency: E-government and social media as openness and anti-corruption tools for societies. Gov. Inf. Q. 2010, 27, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailard, C.S. Mobile Phone Diffusion and Corruption in Africa. Politi Commun. 2009, 26, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haafst, R. On The Effect of Digital Transformation on Corruption; KU Leuven: Leuven, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, D.C.; Eom, T.H. E-Government and Anti-Corruption: Empirical Analysis of International Data. Int. J. Public Adm. 2008, 31, 298–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, L. E-Government and Social Media as Effective Tools in Controlling Corruption in Public Administration. Econ. Manag. Financ. Mark. 2016, 11, 66–72. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Perspective | Experts (Country) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Digital Infrastructure | E. Estevez + (AR) |

| 2 | Artificial Intelligence | C. Chesñevar + (AR) |

| 3 | The Dark Side of ICT | L. A. Joia + (BR) |

| 4 | Rebounds of Smart Cities | M. A. Cunha + (BR) & J. P. Albuquerque (BR) |

| 5 | Economic Change | A. A. Ferraresi + (BR) & C. Quandt + (BR) |

| 6 | Industrial Change | P. Collazzo-Yelpo + (UR) |

| 7 | Big Data in Occupational Health | F. M. Fischer + (BR) & J. S. Silva-Junior * (BR) |

| 8 | Digital Democracy | D. Cardona + (CO) & A. Sanchez + (CH) |

| 9 | Cybercrime | D. R. S. Rios + (BR) & F. C. O. Garcia * (BR) |

| 10 | Corruption | E. M. Luciano + (BR) |

| 11 | Banking & Cryptocurrency | E. H. Diniz * (BR) |

| Unseen | Prop | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Low population density | P1 | CF |

| Low capacity and weak government institutions | P1 | CF |

| Psychological warfare | P2 | IN |

| Digital curtain imposed by internet giants | P3 | CF |

| Users’ perception/acceptance | P4 | IN |

| Need for improved recommendation and explanation capabilities | P5 | IN |

| Use of “black-box” algorithms | P5 | IN |

| Digital image versus information flow among cities’ ecosystems | P6 | SO |

| ICT development reinforcing socioeconomic gaps | P7 | SO |

| Crises of representation | P8 | CF |

| Homo digitalis | P9 | IN |

| Delusion of democratization | P12 | SO |

| Weakening government institutions | P12 | SO |

| Governments in the region lack the ability to adapt | P13 | CF |

| Increasing inequalities | P14 | SO |

| Dematerialization of wealth production | P15 | CF |

| Lack of adaptation of educational systems | P16 | SO |

| Creating and strengthening monopolies/oligopolies | P17 | CF |

| Further inequalities in the labor market | P17 | SO |

| Small farmers becoming powerless | P18 | SO |

| Genetic manipulation of farm products | P18 | SO |

| Bias in reporting data about work-related diseases/injuries | P22 | CF |

| Fewer opportunities for young workers | P23 | SO |

| Social exclusion as a consequence of the rigors of health assessments | P24 | SO |

| Misuse of information due to intentionally poor data quality | P24 | CF |

| Misuse of public funds | P25 | CF |

| Manipulating citizens’ opinions in social media | P26 | CF |

| Manipulating protests | P27 | CF |

| Jeopardizing traditional institutions | P27 | CF |

| Ubiquity of users of digital platforms may exhibit a lack of understanding of local community needs | P27 | CF |

| Raising awareness about socio-economic gaps between countries distorts the equilibrium of many systems | P28 | CF |

| Increasing inequalities | P29 | SO |

| Identifying the offender and place of operation; which jurisprudence? | P30 | CF |

| Lack of admissibility of evidence in court | P31 | CF |

| Underestimated growth of complementary cryptocurrencies | P36 | CF |

| Crypto-engagement of customers as new mechanisms for citizen engagement | P37 | CF |

| The potential of stable cryptocurrency | P38 | CF |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Viale Pereira, G.; Estevez, E.; Cardona, D.; Chesñevar, C.; Collazzo-Yelpo, P.; Cunha, M.A.; Diniz, E.H.; Ferraresi, A.A.; Fischer, F.M.; Cardinelle Oliveira Garcia, F.; et al. South American Expert Roundtable: Increasing Adaptive Governance Capacity for Coping with Unintended Side Effects of Digital Transformation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020718

Viale Pereira G, Estevez E, Cardona D, Chesñevar C, Collazzo-Yelpo P, Cunha MA, Diniz EH, Ferraresi AA, Fischer FM, Cardinelle Oliveira Garcia F, et al. South American Expert Roundtable: Increasing Adaptive Governance Capacity for Coping with Unintended Side Effects of Digital Transformation. Sustainability. 2020; 12(2):718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020718

Chicago/Turabian StyleViale Pereira, Gabriela, Elsa Estevez, Diego Cardona, Carlos Chesñevar, Pablo Collazzo-Yelpo, Maria Alexandra Cunha, Eduardo Henrique Diniz, Alex Antonio Ferraresi, Frida Marina Fischer, Flúvio Cardinelle Oliveira Garcia, and et al. 2020. "South American Expert Roundtable: Increasing Adaptive Governance Capacity for Coping with Unintended Side Effects of Digital Transformation" Sustainability 12, no. 2: 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020718

APA StyleViale Pereira, G., Estevez, E., Cardona, D., Chesñevar, C., Collazzo-Yelpo, P., Cunha, M. A., Diniz, E. H., Ferraresi, A. A., Fischer, F. M., Cardinelle Oliveira Garcia, F., Joia, L. A., Luciano, E. M., de Albuquerque, J. P., Quandt, C. O., Sánchez Rios, R., Sánchez, A., Damião da Silva, E., Silva-Junior, J. S., & Scholz, R. W. (2020). South American Expert Roundtable: Increasing Adaptive Governance Capacity for Coping with Unintended Side Effects of Digital Transformation. Sustainability, 12(2), 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020718