1. Introduction

Global trends towards urbanization [

1], and the related triumph of the city [

2], intersect global phenomena, including the climatic and the pandemic crisis [

3,

4], emphasizing the centrality of the urban realm as the crucible of the human condition in the Anthropocene [

5]. Within this perspective, the ways in which the spatial, material, and social structures of the city affect individual and collective practices emerge as a global issue. Thus, the development of a theoretical and methodological framework for assessing opportunities for people’s practices across public spaces [

6] is central to orient place-shaping processes, particularly within the smart city paradigm and the smart growth model [

7]. The former, in fact, prefigures the prototype of a city that integrates ICTs and data collection and analysis into governance practices to address in a systematic way the issues of the contemporary city, while responding to citizens’ expectations of transparency and accountability. On the other side, smart growth underlines the relevance of density, diversity of land uses, walkability, and transit-oriented development in terms of the sustainability of urban settlements. A further relevant issue concerns the ways in which the articulation of public open spaces can enable co-presence and functional proximity, while ensuring social distancing in the post-pandemic era.

In particular, the place of children’s developmental needs [

8] within the power relationships that orient place-shaping processes [

9] has emerged as a global issue. Today, over a billion children are growing up in cities [

10]. The possibility of significantly engaging with the public space affects children’s bodily, emotional, social, and cognitive development while influencing their conduct and affective relations as adults [

11,

12,

13]. Despite the increasing relevance of this topic within different disciplinary fields [

14], existing methods and techniques for the analysis of public space quality from children’s points of view present several limitations, including: (i) reduction of children’s experience of the environment to distinct behaviors; (ii) partial recognition of impacts of outdoor practices on children’s wellbeing; (iii) failure to understand the effect of configurational factors on children’s behavior; and (iv) failure to recognize the relational character of opportunities embodied into the built environment. Within this perspective, the authors build on the paradigm of soft-physical determinism, and on the inherent relationship between place quality and place value [

5,

6] to elaborate a theoretical and methodological framework for identifying and assessing the attributes of the environment that affect children’s outdoor independent activities. Consequently, this research aims to emphasize children’s experience of the built environment, thus focusing on environmental opportunities and constraints relevant from their perspective and investigating to what extent the built environment incorporates places for children’s autonomous practices, agency and autonomy. With respect to the four issues emerging from the existing literature, this research investigates four aspects: (i) firstly, the concepts of Children independent activities (CIAs) in relation to the multi-dimensional character of children’s experience of public open spaces (POS) are analyzed. Consequently, the concept of meaningful usefulness of a place is introduced. Secondly, the concept of capability [

15] and affordance [

16,

17,

18] are studied. Consequently, usefulness is operationalized in terms of a set of qualitative and quantitative indicators that measure site-specific and contextual factors. These indicators are organized into the Opportunities for Children in Urban Spaces (OCUS) tool and are summarized by the synthetic Index of meaningful usefulness of individual public spaces (IUIS). This article presents results from a research [

14,

19,

20,

21] on the availability of POS to children’s outdoor practices. This research focuses on the definition of the methodological framework, and on the investigation of its usability with respect to: (ii) test of techniques for the conduction of focus groups; (iii) definition of the layout of the OCUS tool, and verification of indicators in terms of availability of input data, computational simplicity and speed, replicability, flexibility, and cost; and (iv) definition of techniques for the results validation and testing in terms of computational simplicity and speed, reliability, and cost.

The proposed methodology is applied to the assessment of significant urban spaces within the historic district of the city of Iglesias in Sardinia (Italy). The city of Iglesias is selected as a case-study for its conditions of demographic and socio-economic crisis. The paper is divided into six sections. After the introduction, a review of literature concerning children’s experiences of outdoor spaces elucidates the theoretical framework by defining the concepts of capability, affordance, and meaningful usefulness. Next, the methodological framework and the case study are described. The results of the application of the audit tool to the case study are presented in

Section 4, and the findings are discussed in

Section 5. Finally, the conclusion discusses the relevance and the limitations of this research and outlines its future development.

2. Literature Review

The issue of the child-friendliness of the built environment is emerging as a relevant aspect of the discourse on the Contemporary city. The impact on children’s cognitive, physical and social development of independent outdoor practices is the focus of studies across different disciplines. Within this discourse different approaches can be recognized: (i) Exploratory research, focusing on the clear definition of research questions related to children’s outdoor activities [

22]; (ii) explanatory studies, focused on cause-effect relationship between built environment factors and outdoor practices, combine the analysis of individual behavior, based on qualitative and quantitative methods, and the measurement of built environment variables via spatial analysis techniques or surveys [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]; and (iii) descriptive research, based on qualitative and quantitative techniques, focus on the description of individual practices and perceptions related to the public space [

28,

29,

30]. Within this perspective, the collection of data related to individual behaviors and perceptions include both qualitative and quantitative methods. Qualitative techniques include focus groups, cognitive mapping activity diaries, surveys conducted through Public Participatory Geographic Information System (PPGIS) tools, systematic direct observation, and interviews. On the other hand quantitative techniques are based on the utilization of accelerometers and GPS devices. Several issues emerge from the existing literature concerning four aspects: (i) the reduction of children’s interaction and dwelling with the material and social environment to specific actions; (ii) the non-exhaustive conceptualization of wellbeing, and of positive effects of children’s independent activities; (iii) the non-recognition of the effects of extrinsic configurational properties of the spatial layout on individual and group activities; and (iv) the failure to recognize the relational character of opportunities and the significance of the plurality and diversity of opportunities as a central determinant of children’s behavior.

More precisely, a relevant proportion of existing studies focus on a specific behavior, thus overlooking the plural, multidimensional character of children-environment transactions and the intimate connection among children’s interactions with the material and social environment. Three tendencies emerge: The first tendency include explanatory and descriptive studies focused on children’s active travel and independent mobility [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Independent mobility is also conceptualized as a proxy to physical activity [

22]. The second tendency include descriptive and exploratory studies focused on play and outdoor activities [

11,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Lastly, the third tendency includes descriptive studies focusing on physical activity and health as the resultant of both independent mobility and outdoor play [

26,

28,

35,

36]. On the other side, descriptive and exploratory studies building on the concept of affordance and affective relation, recognize and investigate the plurality and interplay of children’s functional, social and emotional interactions with the built environment [

12,

23,

37,

38,

39,

40]. A relevant contribution is represented by the Bullerby model [

41,

42,

43]. The latter operationalizes the child-friendliness of an urban environment as the resultant of the number and diversity of positive and actualized possibilities, or affordances, and of the degree of independent mobility.

Furthermore, existing studies tend to conceptualize wellbeing and, consequently, effects of children’s experience of public open spaces, primarily in terms of bodily health cognitive development and socialization. In particular the meta-analytic review conducted by Sharmin and Kamruzzaman [

25] on 13 studies underlines a prevailing conceptualization of well-being in terms of health, within explanatory research aimed at investigating the relationship between built environment and independent mobility. On the other hand, descriptive and explanatory studies that recognize the plurality of children’s interactions with the physical and social environment refer to benefits of outdoor practices in terms of creativity and responsibility [

44], agency and development of tactics [

12], and learning [

38]. Furthermore, Chawla’s literature review on benefits of nature contact for children [

11] introduces a comprehensive formulation, based on the concept of capability, of positive effects of children’s encounter with the natural environment. Within this perspective, well-being is conceptualized as the full development of fundamental human faculties. A further issue emerging from the literature review regards the failure to ground environmental properties in the relationship between attributes of the public spaces and individual abilities. Within this perspective, in fact, a component of the built environment incorporates an opportunity for action only if its attributes fit the abilities of the user or of a specific group of users [

17,

18,

23]. The relational quality of opportunities reflects an accurate account of places experience as mediated by processes of perception-action and a conceptualization of spaces and environmental elements relative to a specific individual and to a specific individual’s activities [

18]. Finally, with respect to the effect of configurational properties of spaces on children’s practices, existing studies tend to focus on the effect of local properties of the spatial layout on active travel, independent mobility, and physical activity. Local configurational properties include connectivity [

36], intersection density [

22,

25,

26,

45]. Consequently, the effect of large-scale topological properties of the urban layout on the accessibility of spaces and on patterns of natural movement, co-presence, and of sense of privacy and territoriality [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51] are largely unexplored. In order to address the criticalities emerging from the literature review, the concepts of Children’s independent activities, usefulness, capability, and affordance are presented in the sub-sequent section.

A Theoretical Framework: Concepts of Usefulness, Capability, and Affordance

This paper focuses on the construction of a methodological framework for assessing the extent to which the spatial, social, and material attributes of public spaces are conducive to children’s independent outdoor activities (CIAs). CIAs are herein defined as the complex of children’s practices carried out without adult supervision. These include independent mobility, or the freedom and/or ability of children to travel across an urban space, play [

33], and creative acts of claiming, interpreting, and appropriating spaces [

52].

The potential of public open spaces (POSs) to enable children’s independent activities is here referred to as usefulness. hence, this concept reflects the conceptualization of child-friendliness as the potential of the public open space to support intense engagement with the environment. Nevertheless, while the concept of child-friendliness, as observed by Whitzman et al. [

22], is encompassed within a social and health planning perspective, the concept of meaningful usefulness is introduced to focus the discourse on child-friendly cities on attributes of the built environment incorporating opportunities for children’s independent activities. Children’s independent outdoor activities are eminently related to positive effects on their well-being [

11,

13,

24,

28,

30,

53]. In general terms, the benefits of outdoor activities can be re-conceptualized through the capability approach. In Sen’s words [

15], a capability can be defined as the ability of an individual to achieve a specific functioning—a ‘doing’ or ‘being’ part of the state of that person–deemed as valuable. Martha Nussbaum [

54,

55,

56], underlines the necessity of individuating a list of capabilities central to good human life. According to Nussbaum, these central capabilities include life; bodily health; bodily integrity; affiliation; practical reason; play; senses, imagination, and thought; emotions; connection to nature; and control over one’s environment [

55]. Within this perspective, well-being can be conceptualized as the full achievement and exercise of fundamental human faculties; hence, the concept of capability is central to the comprehensive conceptualization of the effects of outdoor independent activities on children’s well-being [

15].

Furthermore, the concept of capability implies the availability of different opportunities, as a factor influencing the set of alternative attainable functionings that constitutes the capability set [

15]. In this respect, the external opportunities are conceptualized through the affordance theory. Affordances can be defined as the functional, emotional, and social opportunities and constraints incorporated into a setting in relation to a specific individual or to a specific category of individuals [

17,

18,

43,

57,

58]. Affordances thus incorporate relations between the abilities of a specific group of individuals and the attributes of the environment. Hence, affordances are relational [

18,

59]. This characteristic emphasizes the relevance of the affordance concept within a theoretical framework for interpreting the ways in which the built environment affects the behavior of a specific group of individuals. Specific functional, emotional, and social affordances, affecting patterns of children’s activities, are identified by Heft [

17], Lerstrup and Van Den Bosch [

37], Kyttä [

23], and Broeberg et al. [

38]. These categories, and the attributes of variation and uniqueness, size and gradation, novelty and change, and abundance of environmental features, constitute the foundation of the layout of the OCUS tool, which is described in the following sections.

Lastly, a further class of opportunities influencing children’s independent activities is systematized through the concept of accessibility. According to Moore [

60], both the diversity of resources, described via the functional, social and contextual affordances dimensions, and the access to resources define the quality of children’s environment [

6,

38,

60,

61]. In particular, the movement-related component of accessibility is related to the configuration of urban space. Configuration refers to the topological properties of a spatial structure and can be defined as a set of relationships among parts, all of which interdepend in a citywide structure [

46,

48,

62,

63,

64,

65].

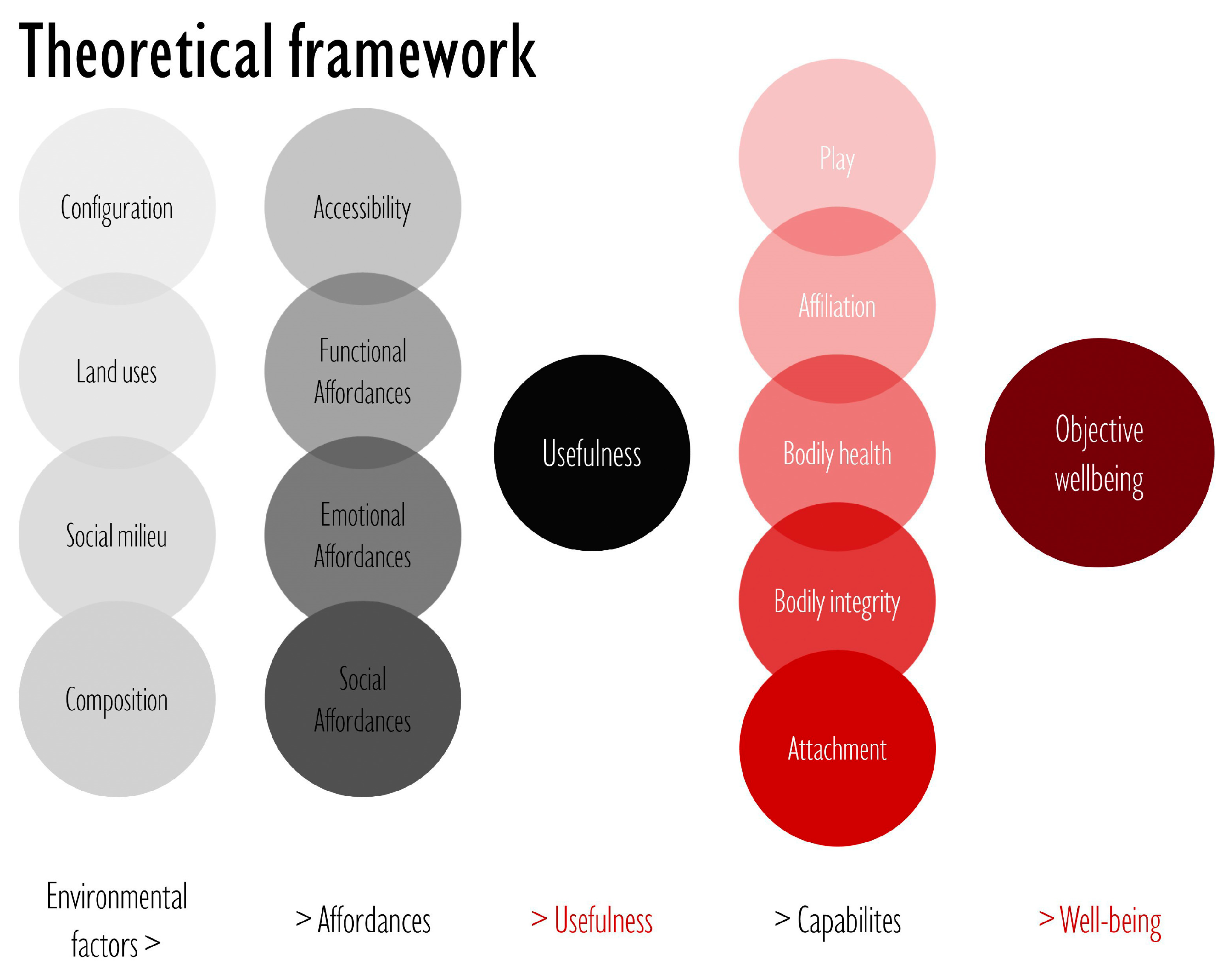

These concepts constitute the theoretical model encompassing a methodology for the assessment of the usefulness of the public space. Within this model, the meaningful usefulness of a setting is determined by the accessibility conditions and by environmental features and amenities [

9] that, in relation with children’s characteristics, produce functional, social, and emotional affordances. The meaningful usefulness of public spaces, in turn, affects children’s well-being by encompassing the external conditions shaping their central capabilities [

55]. In particular, the opportunities for children’s engagement with the built environment are related to bodily health, bodily integrity, or the ability to move freely from place to place, sense, imagination and thought, emotion, herein defined as the ability to develop attachment to things and people, affiliation, play, and control over one’s environment (see

Figure 1) [

11,

52,

54,

55,

66].

In the following section, the Methodological framework for assessing the meaningful usefulness of public spaces and the “Opportunities for Children in Urban Spaces” tool is described.

3. Methodology

The Opportunities for Children in Urban Spaces (OCUS) tool is envisioned as an audit tool that integrates quantitative and qualitative indicators for measuring the conditions of access to open public spaces and the availability, quality, and variety of functional, emotional, and social affordances, that are determined by the conditions of the built environment at different scales (see

Table 1). The OCUS tool combines the analysis of primary data collected during on-site explorations, as well as secondary data collected from territorial informative systems (Sardinia Regional Informative Territorial Service, Open Street Map) and from Internet-based street level imagery services (Google Street View) and territorial imagery services (Google Maps, Google Earth, Bing Maps). The audit tool incorporates a methodological framework organized on six stages (see

Figure 2).

The first stage is the characterization of the case study, consisting in the definition of the area of study and of the group of users in relation to which the meaningful usefulness of a public space is assessed. The second stage is a focus group, involving children, for individuating meaningful places and transactions with spaces and elements of the public space. The third stage is the individuation of environmental features associated with specific affordances and the individuation of indicators according to criteria of objectivity; relevance; measurability and reproducibility; validity; representativeness, comparability over time, applicability, and understanding [

14]. The fourth stage is that of definition of use-value functions and quality thresholds for normalizing and aggregating single indicators. The fifth stage is that of definition of the layout of the Audit tool and of a function for summarizing the single indicators into a synthetic Index of Meaningful Usefulness of public Urban Spaces (IUIS). The sixth stage is that of data collection, measurement of single indicators, and evaluation of the meaningful usefulness of the significant public spaces within the area of study via the determination of the value of the IUIS Index.

Primarily, the developmental character of affordances compels to focus on a specific group of users. The concept of affordance, in fact, refers to condition emerging from the relation between environmental attributes and individual abilities. The configuration of individual abilities, related to specific development stages, thus modifies the set of meaningful opportunities available for the individual, in a setting. Consequently, an element of a space can incorporate an affordance for a specific individual, in relation to their abilities, and a constraint for a different user. The presented research focuses on children attending secondary school and aged between 11 and 14 years. According to Shaw et al. and Carver et al. [

27,

67], this range is consistent with existing studies on children’s experiences of place and reflects sensible variations in children’s levels of independent mobility. In particular, age and school level together emerge as relevant correlates of children’s levels of independent mobility, and, particularly, major progresses in children’s independence coincide with the transition from primary to secondary school. Furthermore, at age 14, the majority of children are allowed to cross major roads, travel alone on local buses, and independently go to school and to relevant places within walking distance from home.

The definition of the case study was based on a focus group involving 24 children, 12 boys and 12 girls, aged 11 to 14 years, from a secondary school located in Iglesias, Sardinia, Italy, the Comprehensive Institute “Eleonora d’Arborea”. In particular, five participants were aged between 10 and 11 years, 12 were aged 12 years, and 7 were aged between 13 and 14 years. All participants resided in Iglesias. The involvement of 24 children was based on the saturation principle and on the phenomenological approach, known in literature on qualitative research [

14,

21,

68,

69,

70,

71].

The subject of the focus group was locating on a map of the city of Iglesias significant functional, emotional, and social affordances. The objective was twofold. On one hand, the objective concerned the individuation of meaningful places, or spaces imbued with behavioral, psychological, and symbolic meaning [

40]. On the other hand, the focus group was aimed at underlining situations and activities valued by children as meaningful; these preliminary findings were used to revise the taxonomy of elements of the public space incorporated into the audit tool.

The focus group was part of a workshop for children between the ages of 11 and 14 on sensory territorial explorations. The aim was to promote and develop children’s abilities to describe the landscape of their everyday practices, and to investigate children’s experience of public space, in order to increase awareness among decision-makers and the general public of children’s right to mobility within a city. The format of the workshop was elaborated in the context of the regional program “Tutti a Iscol@”. The Comprehensive Institute “Eleonora d’Arborea” was the first to volunteer to be involved in the workshop. According to the program regulations, a group of 24 children was selected by the teaching staff, among those interested in the proposed activity. The criteria for the selection of the final group included knowledge of basic principles of photography, as well as a degree of command in the use of apps for editing images and texts.

Environmental features and attributes associated with functional, emotional, and social affordances are then individuated according to the existing literature on children’s independent mobility and place experience, as illustrated in

Table 1. Primarily, functional affordances are related to specific site-specific features: hence, the functional affordances of walking, running, cycling, and playing ball are related to the presence of flat, void, relatively smooth surfaces. Likewise, the affordances of hiding, prospect, and sitting in are associated with the availability of enclosed spaces, hence, a space bounded on three sides or covered by a ceiling of height not superior than 2.50 m. Finally, rigid features include non-movable features (including trees, retaining walls, benches, and stairs) that afford sitting-on, jumping-on/over/down-from, running around, hiding behind, or building on [

14,

17,

19,

37].

Emotional and social affordances, as well as accessibility conditions, are associated with both site-specific attributes and with large-scale factors related to the configuration of the urban structure, to density, and to land-use patterns. For instance, the emotional affordance of feeling safe is associated with the natural surveillance of the public space [

72], which in turn depends on the perception of social incivilities, configurational aspects of the urban structure influencing pedestrian movement, and compositional aspects of a public space. Natural surveillance is thus operationalized in terms of sub-indicators assessing the visibility of the nearest buildings, the interactivity of facades and residential density [

73,

74], the presence of signs of neglect, and/or the evidence of antisocial practices [

24]. Moreover, the compositional aspects include prospect, or the ability to see into a place where someone can be hiding, and boundedness, defined as the degree of enclosure of a space that limits the possibility to escape [

75]. Finally, configurational aspects refer to local normalized angular choice [

47], or the probability that a space comprises the shortest paths among all pairs of spaces in the urban structure.

The affordance of being in a pleasant place is associated to with the conspicuousness of a space, which is operationalized via the indicator imageability of the public space. The latter aggregates sub-indicators that assess the presence of unique elements—including public art, ruins, geological/vegetation formation [

9]—the visibility of major landscape features [

76], the articulation of edges [

20]—related to the heterogeneity of spatial conditions along the boundaries of a space—and the complexity and density of retail activities and services. The latter refers to the number of store frontages per 100 m of linear extension of facades delimiting a particular public space. According to Gehl [

73], in vibrant public spaces, retail activities frontages are between 5 and 6 m wide, thus corresponding to between 15 and 20 interactive façades in 100 m.

The affordance of meeting friends is associated with the significance of a space as a meeting place, according to its through-movement potential, and the possibility of making new friends is associated with the proximity of anchor places, hence primary functions determining the concentration of users, including educational institutions and sport and recreational facilities. Furthermore, the sense of privacy and territoriality is associated with the proximity of public spaces to the primary lines of pedestrian movement. In fact, according to Hillier [

46], children tend to concentrate in the most integrated spaces distinct from spaces of adults’ natural movement. Finally, the conditions of accessibility of a space are associated with its potential to attract movement, prioritize vulnerable users, and to connect with comfortable pedestrian and bicycle facilities.

Finally, with respect to the indicators assessing built environment correlates of independent access to public space, the indicator ‘R400 angular integration’ measures the to-movement potential of a space, or its potential as a destination. This potential is conceptualized as the resultant of the proximity of a space to all other segments, within a radius of 400 m, in terms of the sum of angular changes that are made on each route. Selecting a set of spaces within a 400 m radius, in particular, is instrumental to the analysis of patterns of pedestrian movement [

48].

The qualitative and quantitative indicators and sub-indicators are organized into four categories: (i) functional opportunities, (ii) social opportunities, (iii) emotional/contextual opportunities, and (iv) independent accessibility opportunities.

The individual indicators are then normalized by assigning a score ranging from 0 to 4, as illustrated in

Table 2, where 0 indicates a poor condition, 1 equals inadequate, 2 adequate, 3 corresponds to a fair/good condition, and 4 indicates an optimal condition. The score varies according to the level of performance established, for each indicator, according to a qualitative or to a quantitative scale. In particular, for quantitative indicators, levels of performance correspond to bands of values, determined by subdividing in equal intervals a range defined by the minimum and maximum values observed in the area of study or based on threshold values derived from the literature (see

Table 2).

With respect to the functional opportunities dimension, in particular, each indicator is determined by first calculating the mean of the values of sub-indicators measuring the quantity, variety and uniqueness, regularity, and size and gradation of a specific class of environmental features, and then by weighting the result according to a sub-indicator that expresses an availability measure. This availability-related sub-indicator is conceptualized as a factor ranging from 0.1 to 1 where values close to 0.1 indicate limited availability of affordances and values close to 1 reflect opportunities for children to freely actualize potential affordances. Hence, the availability-related sub-indicator expresses to what extent socio-cultural constructs (including norms, habits, conceptualizations, and shared values) or physical constraints inhibit children’s independent activities. More specifically, constraints include restrictions on accessibility, regulations preventing specific activities, conflicts among children’s practices and adults’ activities, time or coupling constraints determined by adults’ control of specific facilities or amenities, and the manicuring of spaces [

11,

44]. Furthermore, regarding indicators that measure configurational properties, in case a space is intersected by several segments, the value of the configurational variable equals the value calculated for the most integrated segment, if the longest dimension of the considered space is less than 70 m; otherwise, the value of the indicator related to the configurational variable is equal to the mean of the values calculated for all the segments that intersect the considered space. The 70-m measure is derived from Gehl [

73] and is indicated as a relevant social distance that influences the significance and content of interactions among individuals.

For each affordance category, the relative single indicators are then aggregated into a synthetic index. Hence, a functional affordances index (If), a social affordances index (Is), an emotional affordances index (Ie), and an independent accessibility index (Ia) are computed. Each index is calculated dividing the sum of the values determined for the relative individual indicators by a potential value, which is determined as the sum of the maximum values assignable to each indicator. Hence, each index is expressed by a value ranging from 0 to 1, where values close to 0 equal marginal quality of the public space, and values close to 1 indicate good to optimal conditions in terms of opportunities for children’s independent practices (see in detail in

Table 3).

Next, the Index of Meaningful Usefulness of public Urban Spaces (IUIS) is calculated (

Table 3) in two steps. Primarily, the sum of the values assigned to single indicators included in the functional, emotional, and social affordances categories is divided by their potential maximum value. Then, the resulting value is multiplied by the value of the Independent accessibility Index. The result is a value ranging from 0 to 1. The IUIS index, thus, synthetically expresses the usefulness of a space as the resultant of the quantity, quality, and variety of opportunities for significant experiences incorporated into environmental features, mediated by the possibility of perceiving and actualizing potential affordances. The latter, in turn, is related to conditions for frequent and independent access to a specific public space.

For the IUIS index, values close to 1 refer to optimal levels of meaningful usefulness of the public space and values close to 0 refer to marginal levels of inclusivity of a setting from children’s perspective (see in detail in

Table 3).

This article focuses on the presentation of OCUS procedure, and on the investigation of its usability via its application to a set of public spaces across the historic center of the city of Iglesias. Further clarifications on the criteria for the selection and characterization of the case study are presented in the initial paragraph of the succeeding section.

Selection of the Case Study

The proposed methodology was applied to the assessment of meaningful urban spaces within the historic district of the city of Iglesias in Sardinia (Italy) (

Figure 3). The city of Iglesias was selected as a case study for its particular demographic and socio-economic conditions, including the modest percentage of residents aged between 11 and 14 years, depopulation, and stagnant economy. In fact, regarding the first issue, children aged between 11 and 14 years represent the 2.8% of the population compared to a national average of 3.7%, a regional average of 3.3% and to a value for the city of Cagliari of 2.8% [

77].

The trend toward depopulation was confirmed by the loss of 929 inhabitants in the time span 2014–2019—from 27,444 to 26,515 inhabitants—, equal to a decrease of 3.4%, while economic stagnation was underlined by the gap in terms of GDP per capita with the national and regional average. In fact, for the city of Iglesias the GDP per capita was equal to 19,200 euros per year, compared to a national average of 26,000 euros per year, a regional average of 20,600 euros per year, and a value of 25,681 euros per year for the city of Cagliari, which represents the administrative center of the Sardinia Region [

78,

79,

80]. Building on the examples of Sidney, Rotterdam, and Vancouver [

81,

82], interventions aimed at increasing the inclusivity, liveliness, and usefulness of public spaces from the point of view of children are instrumental in making cities attractive to families, attracting and retaining a skilled workforce, and, thus, driving a local economy and reversing trends toward depopulation.

The OCUS tool was been applied to the analysis of nine public open spaces within the historic district of the city of Iglesias, selected during the workshop of territorial sensory exploration. The historic districts of Iglesias are characterized by a compact structure and present several characters conducive to child-friendliness: mixed uses, a continuous network of pedestrian areas and limited traffic routes, an integrated spatial structure, pedestrian accessibility, and diversity in terms of retail, cultural, and commercial offerings, including a theatre, libraries, accommodation structures, restaurants, cafès, and shops.

Within this area, nine public spaces are selected as units of analysis according to their relevance as places. A place is herein defined as a portion of space where meaningful representation of, and emotional connection to, settings and people are formed [

51]. Consequently, in the first stage of the workshop, children were presented with a map of the city of Iglesias and asked to locate meaningful places in terms of actualized affordances. Then, once the set of meaningful places was established, five itineraries of sensory exploration were defined. Each itinerary investigated a specific theme related to a specific functional, symbolic, or behavioral value attributed by children to the public space. The five themes were: (i) food, (ii) meeting places, (iii) transitory spaces, (iv) space of memory, and (v) boundary spaces. Spaces incorporating different functional, symbolic or behavioral values were then selected and analyzed via the OCUS tool. This set of spaces thus includes Quintino Sella Square, Giacomo Matteotti street, Cagliari street, Lamarmora Square, Pichi Square, Municipio Square, Collegio Square, and San Francesco Square (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

In the following section, the results of the application of the OCUS tool are presented, and the meaningful usefulness of the selected public spaces is analyzed.

4. Results

The application of the Tool to the case study, as illustrated in

Table 4, reveals that the meaningful usefulness of the selected places is marginal for Collegio Square (IUIS equal to 0.28), San Francesco Square (IUIS = 0.27), and Salvaterra Castle (IUIS = 0.06) and modest for the remaining spaces, with values of IUIS ranging from 0.35 for Cagliari Street to 0.43 for Quintino Sella Square. (

Figure 6).

In particular, the modest levels of meaningful usefulness are influenced by the limited availability, quantity, and diversity of functional affordances incorporated in the built environment. In fact, with regard to the index of functional affordances, as illustrated in

Figure 7, the usefulness of the public spaces is assessed as fair for Q. Sella Square (I

f equal to 0.68), adequate for Salvaterra Castle (I

f equal to 0.62), poor for Municipio Square and San Francesco Square (I

f equal, respectively, to 0.23 and to 0.32), and null for the remaining places (I

f ranging from 0.03 for Collegio Square to 0.09 for Via Cagliari). A different situation is observed regarding emotional and social affordances. In particular, the values calculated for the index of emotional affordances range from 0.57 for Salvaterra Castle to 0.96 for Via G. Matteotti, thus denoting levels of usefulness, in terms of opportunities for meaningful emotional experiences, ranging from adequate to optimal (

Table 4) (

Figure 8). In particular, conditions determining the perceived safety of public spaces were assessed as optimal for Q. Sella Square, La Marmora Square, and G. Matteotti Street; as good for Municipio Square, Collegio Square, Pichi Square, and Cagliari Street; as fair for San Francesco Square; and as poor for Salvaterra Castle. Likewise, the selected public spaces incorporate opportunities for social interactions to a great extent in the cases of Collegio Square, La Marmora Square, Pichi Square, and Municipio Square (I

s equal, respectively, to 0.85, 0.85, 0.85 and 0.8). Adequate levels of usefulness, in terms of social affordances, were also observed in Q. Sella Square, G. Matteotti Street, and Cagliari Street (I

s equal to 0.75). On the other hand, a scarcity of opportunities for significant social interactions was observed in San Francesco Square (0.45) and in proximity of Salvaterra Castle (I

s = 0.10) (see in detail in

Table 4 and

Figure 9).

Finally, the Index of independent accessibility (Ia) reveals that children’s possibilities for autonomously and safely accessing the public space are high in the cases of G. Matteotti Street, La Marmora Square, Pichi Square, Municipio Square, and Cagliari Street (I

a, respectively, equal to 0.75; 0.75; 0.75; 0.69; 0.67); adequate for Q Sella Square and Collegio Square (I

a equal, respectively, to 0.57 and 0.56); modest for San Francesco Square (I

a = 0.52); and marginal for Salvaterra Castle (I

a = 0.14) (

Table 4 and

Figure 10).

In particular, the priority of vulnerable users, measured by the Barrier effect indicator, is maximum for G. Matteotti Street, Cagliari Street, La Marmora Square, Pichi Square, and Municipio Square (measures ranging from 0.94 to 1); high for Collegio Square (0.75) and San Francesco Square (0.81); medium in the proximity of Salvaterra Castle (0.56); and limited for Q. Sella Square (0.53).

Moreover, the to-movement potential of a space, and hence its potential to emerge as a destination, measured by the Angular Integration within a 400 m radium (R400 AI), is significant for Collegio Square, G. Matteotti Street, La Marmora Square, and Pichi Square (R400 AI values superior than 127.54); good for Q. Sella Square, Cagliari Street, Municipio Square, and San Francesco Square (R400 AI values ranging from 96.43 to 127.53); and scarce for Salvaterra Castle (R400 AI values inferior than 34.21).

A thorough discussion on the results obtained from the analysis of the public space is presented in the subsequent section.

5. Discussion

The results presented in the previous section reveal a set of criticalities both at the scale of the single setting and of the system of public space. An emerging issue concerns the spatial and physical attributes of individual spaces [

40]. The geometry, size, and organization of spaces limit the quantity and variety of the functional affordances. Thus, the absence of repaired spaces limits children’s possibilities of retiring, hiding, or being on their own. Second, both the irregular shape and limited extension of regions of open grounds and the lack of morphological variety reduce opportunities for physical activities, such as running, cycling, skating, and for structured group activities including playing ball. Furthermore, the lack of rigid elements reduces opportunities for informal play activities, including jumping, climbing on, running around, balancing acts, and for sitting and resting. A further aspect, emerging from the values of the Index of functional affordances calculated for Q. Sella Square and Salvaterra Castle, is the evident association between the complexity of vegetal formations and the increase in the quantity and variety of functional affordances. In fact, treed areas afford different types of activities, including climbing-on, hiding behind, refuge, balancing acts, utilization and manipulation of loose objects, and observation [

17,

37,

83]. These different activities generate significant nature situations, which in turn shape the psychological traits of human-nature connections [

83], while significantly contributing to the development of central capabilities [

84]. A related aspect concerns the availability of potential affordances. In fact, adults’ control over and ownership of public space, implemented through manicuring of spaces, occupation, regulations, and time or coupling constraints, reduce the likelihood of children perceiving and actualizing the potential affordances [

12,

14,

22]. Further issues are related to the configurations of networks of pedestrian spaces and the organization of road spaces. The interference and conflict between pedestrian movements and traffic flows—determined by conditions of adjacency and overlap of surfaces for vehicular mobility and pedestrian spaces, geometrical and functional characters of crosswalks, inadequate visibility, and lack of measures of traffic control—produce a barrier effect that negatively affects opportunities for children’s access to and appropriation of meaningful places. Moreover, the absence of a diffuse and continuous network of bicycle paths emerges as an additional constraint to children’s agency and independent mobility. These factors reflect an organization of public space that reduces the total space available to children within the city, both in physical and in symbolic terms: public space spatializes, through strategies of segregation into controlled environments, the marginalization of children’s needs and of their right to participate in the city’s life. This phenomenon further increases children’s psychological distance from the adults [

8].

In particular, complexity emerges as a fundamental compositional aspect of public space. Complexity refers to the density of differences within a structure or a space and thus depends on the variety of morphological, material, and functional characteristics and on the arrangement of the elements of a space [

76,

85,

86,

87]. Hence, complexity is related to visual richness, imageability, and the quantity and variety of possible meaningful actions, thus increasing both the functional and emotional affordances incorporated into a public space.

These considerations call for an integrated urban design strategy, aiming to enhance the intrinsic, local attributes of public open spaces, particularly their complexity and the continuity and connectivity of walkable surfaces, hence reinforcing the usefulness, accessibility, and attractivity of the public space from children’s perspective. This strategy actualizes the shift from a tokenistic approach to the issue of the child friendliness of the contemporary city, to a citizenship approach [

22] to place-shaping processes [

88]; the latter acknowledges the impact of opportunities for independent mobility and outdoor activities, encompassed in the usefulness of public open spaces, on children’s well-being. Lastly, the robustness and predictiveness of the methodological framework should be verified through a validation stage, based on the comparison between estimated levels of public space usefulness and users’ actual patterns of activities, preferences and attitudes towards specific settings. In particular, the validation stage is central to underline three distinct aspects: (i) discrepancies, between an expert evaluator and a child, in the perception of the activities, social interactions and emotional experiences afforded by specific environmental features; (ii) the relative importance attributed by children to specific affordances; and (iii) the adaptation of children to specific constraints determined by the spatial, material and social conditions of the public space. For instance, the values of the I

UIS Index are relevantly influenced by contextual factors, including proximity to anchor places, choice or through-movement potential, and integration. Yet, contextual factors could be less relevant, from children’s perspective, than micro-scale specific factors related to compositional, functional, and social attributes.

In conclusion, the findings of the presented study and a perspective for the development of the research are outlined in the sub-sequent paragraph.

6. Conclusions

This paper describes research that builds on the notion of soft physical determinism to investigate the extent to which the built environment affects children’s independent activities and support their well-being. In particular, this article aimed to present and to illustrate the usability of a methodological framework for the assessment of the usefulness of the public space. This study contributes to the literature on child-friendly cities in three ways. Firstly, authors derive from different disciplinary fields the concepts of affordance and capability which are still largely neglected within the field of urban planning. Yet, as argued in the literature review section, they are central categories for conceptualizing opportunities for experience embodied into the built environment and the ways in which the latter affects children’s well-being. Secondly, this study introduces the conceptualization of the quality of the Public space as the resultant of both its intrinsic social, morphological, and material characteristics and of its extrinsic properties determined by land-use distribution and by the topology of the urban layout.

Consequently, the third relevant aspect of this study is the utilization of space syntax techniques to analyze the impact of configurational properties of centrality on the quality of the public space from children’s perspective. Thus, the proposed methodological framework operationalizes the combined influence of intrinsic and extrinsic variables on the usefulness of the public space by integrating qualitative indicators, quantitative indicators, and Syntactic measures within a multi-criteria analysis framework.

The OCUS tool can support different stages of the planning process, particularly (i) the individuation of criticalities of individual spaces; (ii) the evaluation of alternative scenarios of urban regeneration at different scales, in terms of their impact on children’s opportunities to meaningfully engage with public spaces; and (iii) monitoring of interventions of regeneration via the comparison of levels of meaningful usefulness over time.

On the other hand, the research reveals three limitations, related to: (i) the need to consider the effect of specific local context-related factors—including cultural constructs and parents’ socio-economic status—and individual aspects—including abilities, interests and needs, age, and gender—on children’s patterns of activities across the public space; (ii) the limited participation of children in the workshop of sensory territorial explorations (25%); and (iii) the pertinence of comparing public spaces different in terms of scale, function, and morphology.

As a result, the future development of the OCUS tool should focus on three aspects. The first is the utilization of techniques of consensus building during the stakeholder sessions, structured to involve panels of children, experts, and parents. The objective would be achieving a convergence of opinions among the stakeholders about the relative importance of environmental features, so as to accordingly weight the indicators. Furthermore, stakeholders’ sessions should focus on the extent to which the pandemic crisis, while affecting patterns and modes of social interactions and individual practices, redefines the notion of useful places, and, thus, requires the modification of the set of criteria for the analysis of built environment quality. The second aspect is the utilization of PPGIS methodologies to support the individuation of meaningful places, through the mapping of significant, actualized affordances, and to support the stage of the validation of the results obtained via the OCUS tool.

More precisely, the utilization of Public Participatory GIS (PPGIS) techniques [

23,

39] aimed to: (i) increase participation and reach a wider range of potential users; (ii) use a wide range of standard question types and location based question types; (iii) collect and categorize reliable location based data in a simple and cost effective way, through an integrated analysis tool; and (iv) improve the understandability of data visualization.

The third aspect incorporates both the definition of a taxonomy of public spaces based on morphology, scale, and function, and the determination of an optimal level of meaningful usefulness specific for each category. As a consequence, the future development of the research will aim to enhance the effectiveness of the OCUS methodology in orienting the planning process and the decision-making process through the acknowledgement of children’s needs and interests. According to the objectives and theoretical premises embodied in the smart city paradigm, the objective is the creation of a flexible, simple, cost-effective tool for supporting the implementation of strategies of urban renewal and urban regeneration aimed at building sustainable cities and communities, reducing segregation and spatial inequalities via the re-configuration of public space.