Abstract

In Medellin, during this last decade, the municipality and the private sector have been very active in the reconstruction of the city’s war-torn image. With the acknowledged objective of attracting foreign investments and tourists, the second city of Colombia has been consecutively branded as “innovative”, “smart”, “sustainable” and lately as a “resilient city”. Since 2016 and the integration of the city as one of the first members of the “100 Resilient Cities” network pioneered by the Rockefeller Foundation, Medellin’s authorities have emphasised “urban resilience” as a core value of the city and its residents. Until now, few studies have put into perspective the notion of “branding” with that of “resilience”. By looking closely at discourses on the promotion of the city, as well as its burgeoning tourism sector, this article aims to fill this gap by providing a thorough analysis of the way urban resilience is used as a city-brand in a city still struggling to overcome high levels of violence. This study aims to show that antagonists’ visions of resilience are at stake when comparing the branding discourses of public authorities and the representations of self-settled communities who are at the centre of these narratives. While branding discourses praise the resilience of Medellin communities, many in these same communities tend to reject this vision of resilience as self-reliance (adaptation) and instead call for structural changes (transformation).

1. Introduction

Medellin has transformed itself into a vibrant city, after living through decades of violence. While the situation of the second city of Colombia is far from being normalized and a high level of insecurity still prevails, especially in its marginal neighbourhoods, the significant drop in homicides and the important investments in the city’s urban fabric have often been characterized as a “miracle”. Unfortunately, Medellin, like the rest of the country, has been badly impacted by the global health crisis that started in early 2020, leaving its habitants in lock-down and almost halting the many developments undertaken since the beginning of the new millennium. However, well before the explosion of the pandemic crisis, the real impact of “Medellin’s miracle”—labelled in academic and political language as “social urbanism”—have been progressively called into question. Launched in 2006, the social urbanism program was based on important investments in mobility, culture and education in the most deprived areas of the city. Nowadays, although this program is still an important source of pride for the residents of these peripheral neighbourhoods, more and more critics question the real impact of these investments, beyond city-branding.

Over the last decade, the municipality and the private sector have been very active in the reconstruction of Medellin’s war-torn image. With the acknowledged objective of attracting foreign investments and tourists, the second city of Colombia has been consecutively branded as “innovative”, “smart”, “sustainable”, and lately as a “resilient city”. Since 2016, when the city became one of the first members of the “100 Resilient Cities” (100RC) network pioneered by the Rockefeller Foundation, Medellin’s authorities have emphasised “urban resilience” as a core value of the city and its residents. Since then, urban resilience has been one of the main elements in the branding of Medellin; targeting on the one hand foreign investors by highlighting the resilience of its economy and urban fabric due to its innovations, and on the other hand targeting foreign tourists through the presentation of the resilience of its communities and the way they coped with years of violence.

The main objective of this contribution is to analyse the emerging tourism sector of the city, especially the development of so-called “community tourism” in marginal areas of the city, looking closely at the way urban resilience is placed centre-stage and how it contributes to the construction of Medellin’s brand. The aim is to demonstrate that various and sometimes competing definitions and conceptualizations of “resilience” among stakeholders and residents can lead to conflicts and tensions. A close examination of a sustainable mobility project will be undertaken: the outdoor electric stairs of the comuna 13, commonly referred to as Las Escaleras, which became a paramount element in the branding of the “new Medellin”. Initially intended to improve the mobility of approximately 12,000 residents of some informal settlements in the western periphery of Medellin, this project, internationally branded as one of the main features of social urbanism, and then integrated into the city tourist-scape, became one of the main tourism landmarks of the city before the pandemic crisis. This case study will shed some light on how an urban project associated with sustainable mobility and urban resilience was drawn into the tourism and branding sphere and how its main function shifted from mobility to city-branding and then tourism. Moreover, it will closely examine how the residents of the neighbourhoods surrounding Las Escaleras have been integrated into, or excluded from this project, and more generally how their neighbourhood has been transformed into a tourist destination. By giving a voice to the stakeholders involved, as well as to the residents, the aim is to demonstrate that the shift in the function of Las Escaleras from mobility to branding and tourism is a source of tension, undermining its adoption by the local population and contributing to doubts about the real impact of social urbanism. It is stated here that the use of Las Escaleras in the branding of Medellin and the success of the associated tourism practices led to an important phenomenon of “over-tourism” [1] that significantly eroded its role as a social and community project.

The following paragraphs are structured as follows: firstly, after presenting some theoretical insights, the context of the study will be described, with a focus on the integration of Medellin in the 100RC initiative and on the mobilization of the idea of resilience in the emerging tourism sector. Secondly, after briefly presenting the methodological corpus, some empirical ethnographic data will serve to demonstrate the tensions that competing perceptions of resilience can generate when this notion is promoted as a city-brand. Finally, a discussion will put these results in perspective with emergent research looking specifically at the 100RC program, as well as at the debate calling for a deconstruction of what are generally referred to as “global cities”.

2. Theoretical Framework

An important corpus of literature examines the links between “place identity” and branding [2,3,4,5,6]. The importance of branding for tourism destinations has also generated interest in academia and practice [7,8,9,10,11]. However, few studies have put these notions of “branding” and “place identity” into perspective with that of “resilience”. This article aims to fill this gap by providing a thorough analysis of the way urban resilience is used as a city-brand.

From Masdar City to Barcelona, cities are promoted as global models through labels and brands such as “sustainable cities” [12,13], “creative cities” [14,15], “smart cities” [16,17] or even “happy cities” [18]. From 2010, the “resilient city” made a similar appearance on the branding stage, mainly through the promotion of urban resilience in several global programs of development (e.g., 100RC, C40, “Making Cities Resilient” Campaign of the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR)). Fastiggi et al., [19] underline the absence of studies describing how resilience is incorporated into city governance. Studying these global resilience initiatives allows us to understand how this notion impacts city governance practices, among others. In addition to municipalities, private partners and civil society actors are also important players in these programs. Therefore, if we want to explore the way resilience integrates a city practice such as branding, every stakeholder needs to be considered. This is one of the main objectives of this contribution, using an ethnographic analysis of these practices and discourses.

Since Holling’s founding work [20], much has been written on the notion of “resilience” in ecology, disaster studies and social sciences. It would take us beyond the limits of this study to relate the whole history of this contested concept. For the sake of this study, it seems nevertheless important to look at two opposing conceptualizations of resilience: its integration in international discourses of development and the criticisms it generated. Vale and Campanella [21] significantly contributed to situating “urban resilience” in academic discussion with their collective volume, The Resilient City, where the resilience of cities is demonstrated by the fact that, despite rare exceptions such as Pompeii, cities are usually able to survive most crises. Urban resilience is defined in this work as the capacity of cities to absorb a perturbation and to retrieve its functions. This systemic approach to resilience, primarily developed in the context of natural disasters, has been well integrated in the narratives of international organizations, NGOs and foundations. However, the objectives of evaluating and measuring resilience, as well as conceiving policies to enhance it, have been largely called into question since then. The main criticism relates to the blurry definition of resilience. Is it an analytical or operational tool? Who or what are the resilient subjects/objects? Most of all, is resilience desirable? [22,23,24,25] In this vein, critics also consider resilience as a neoliberal tool, emphasizing the depoliticization and the public disengagement this notion may trigger when integrated into development discourses [25,26,27,28]. Some scholars even state that slums are the most resilient elements of urban areas, pointing to the strong adaptation capacity of their residents in the face of adversity [22,23]. These criticisms echo to some extent those related to the widespread usage of sustainability from the 1980s on. For Kuhlicke [29], resilience is “what was sustainability in the 80′ s and 90′ s”. Julian Reid [26] points out that if sustainability emerged initially as a neoliberal counter-critique of development, it nevertheless gave liberalism’s economic reasoning an even more powerful footing. For Reid, concerns over resilience and sustainability have been co-opted by the very neoliberal model which prompted them to emerge in the first place [26] (p. 69): “Crucial to this story is the relatively recent emergence of the discourse of resilience. […] Having established how sustainable development, via its propagation of the concept of resilience, naturalizes neoliberal systems of governance, I want to consider how it functions to make subjects amenable to neoliberal governance.”

The “resilient city” is thus often considered in the light of the “sustainable city” [30] either as an analytical tool to create indicators to evaluate the resilience of a city, or as a governmental tool shaping city policies. However, building on the criticisms outlined above, Kuhlicke, like Felli [29,31] caution us against the use of resilience terminology to gain legitimacy while still operating traditionally, thus reinforcing a status quo in opposition to demands for change. This poses the question already widely addressed in the literature on the different conceptions of resilience as transformation and as adaptation. As the results presented below will demonstrate, these two opposing visions are sources of tension. While promotion and branding discourses praise the resilience of Medellin communities, many in these same communities tend to reject this vision of resilience as self-reliance (adaptation) and instead call for structural changes (transformation).

As outlined below, the “vagueness” of resilience discourses [32] adequately integrates branding narratives which tend to exclude the many nuances that resilience implies. Indeed, the main objective of branding discourses is not to account for the diverse and sometimes conflicting definitions of resilience, but to propose a clear-cut and positive image of the city. The critical corpus on resilience and sustainability exposed above allows us to pay close attention to the power dynamics involved when such notions integrate the branding sphere. City-branding can no doubt impose a hegemonic conception of the city and its resilience, eventually creating important conflicts when some residents feel they are excluded or, worse, instrumentalized, in these narratives and representations of the city. As Timon McPhearson [33] states, the large overlap in the meaning of resilience and sustainability threatens to weaken both concepts: “Resilience is now being bantered around as sustainability has been for more than a decade, which is to say with little meaning and often as a label to fit conveniently on top of pre-existing agendas”. As in the case of the “sustainable city”, resilience is promoted as an urban label associated with what should be a “good city” and “good citizens” [24]. Crot [34] demonstrates that these labels have imposed themselves in such a hegemonic way that even authoritarian governments are now applying them.

In this special issue, Ginesta et al., [35] (p. 4) also underline that residents should take an active role in a place branding process: “By far the biggest challenge for place brand managers is the role of residents as citizens, as they could ‘make or break’ the whole place branding effort”. For them, it is as citizens that residents legitimize the efforts to brand places. The case of Medellin presented below will serve to illustrate some of the challenges that this process may imply.

3. Background Context

After decades of violence, the city of Medellin underwent a spectacular change. During the mandate of mayor Sergio Fajardo (2004–2007), an ambitious program of urban development entitled “social urbanism” was launched. During his four-year term, Fajardo contributed to the construction of parks, libraries, social housing, as well as sports, health and educational centres in the periphery of the city. In addition to improving the conditions of residents in marginal areas of the city, this program significantly contributed to the fame of Medellin, which progressively became an example of good practice in urban design. The city received several international awards (e.g., the Curry Stone Design Prize, the Harvard’s Green Prize in Urban Design, the Most Innovative City Award by the Urban Land Institute, the Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize) and hosted the UN-HABITAT 7th World Urban Forum in 2014.

Social urbanism is partly based on an interpretation of the “right to the city”, a concept introduced by Henry Lefebvre [36] and strongly influenced by Jordi Borja [37] in the Colombian context. When developing urban projects in territories affected by criminality and poverty, urbanists and politicians paid special attention to citizen participation in order to rebuild bonds of trust that had been broken in previous decades. The “Integral Urban Project” (Proyecto Urbano Integrale—PUI) is the municipality’s main tool for developing social urban projects in the city margins. Moreover, the PUIs aim to improve the image of the barrios populares, the popular neighbourhoods of Medellin. Among the most iconic objects of social urbanism are the Metrocable (urban gondolas), the park-libraries, the outdoor electric stairs of the comuna 13, as well as the construction of many state-of-the-art schools and sport centres.

Hence, after being praised as a model of security, Colombia’s second city also became a global model of urban innovation. The international image of Medellin, often described as “the most innovative city in the world”, and the focus on the development of its informal and poor neighbourhoods, placed the city as a key player in several international programs, some of them featuring urban resilience, and especially the most important ones such as C40 and 100RC. The latest, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation from 2013 to 2019, integrated Medellin as one of its first members. Beyond an important network and technical advice, members of this network received a grant from Rockefeller allowing each city to hire a Chief Resilience Officer (CRO) for two years. The main task of the CRO was to coordinate all municipality actions associated with urban resilience and implement a Resilience Strategy produced by each member city. As all the actors involved in the integration of Medellin in 100RC commented, the singularity of Medellin in this network was its resilience within a context of violence. While New Orleans became the 100RC flagship linked to resilience towards flood disaster, Medellin became the one associated with systemic violence.

Finally, from 2010 on and with growing numbers of international tourists, the “innovative Medellin” and its “resilient population” was progressively integrated into the city touristscape. Following the official visits of international architects, urban designers, politicians and students, Medellin saw an increasing amount of local and international tourists interested in its transformation from “the most violent to the most innovative city in the world.” [7] Sensing a new niche, many guides started to offer tours on the transformation of the city—the Metrocable featuring as the main highlight—and some residents of the barrios populares—mainly local artists involved in urban art—offered to guide visitors to some of these neighbourhoods which were no-go areas not long ago. In this context of urban transformation, tourism clearly served as an efficient means to rebrand these informal and violent neighbourhoods, as well as the city as a whole.

Two areas of Medellin serve as fine illustrations of the relations between resilience branding and tourism promotion: The comuna 13 in the western periphery and Moravia, an informal neighbourhood situated close to the centre. Both areas experienced high levels of violence in the 1990s and at the beginning of the new millennium: at first this was mainly due to bandas, many related to Pablo Escobar and the Medellin Cartel, especially in the case of Moravia; then came issues with urban militias associated with the guerrillas and the ensuing takeover by paramilitary forces. The comuna 13 and Moravia were also crucial areas associated with social urbanism and consequently had an important role in promoting resilience and innovation narratives, generating an increasing interest from the outside world.

Moravia is a large neighbourhood close to the city centre; its proximity to many institutions and services (hospitals, bus terminal, universities, shopping centres and other commodities) makes it a very strategic place for urban development. A large city project of urban regeneration, intended to transform this informal area into a brand-new modern neighbourhood, has triggered a strong movement of resistance within the local community. However, resistance is certainly not a new feature of Moravia and its communities. The neighbourhood was founded during the second half of the 20th century by displaced families who took advantage of “El Morro”, a former municipal garbage dump, to make a living from recycling. When the municipality decided to close the dump and relocate its residents, a large resistance movement took place. Nowadays, Moravia is certainly one of the places in Medellin that has most fully integrated the resilience discourse. Nevertheless, it is also an outstanding illustration of some of the antagonistic visions that resilience may trigger. For the municipality, the resilience of Moravia can be seen in its transformation from a slum situated on a dangerous and insalubrious rubbish dump, and characterized by a high level of violence, into a neighbourhood that is still undergoing improvement and which is now host to a state of the art cultural centre famous throughout the city.

Internationally, the comuna 13 is certainly the best-known area in Medellin. Like Moravia, most of its neighbourhoods were informally built by displaced people during the second half of the 20th century. Unlike Moravia, which is situated in the valley, most of comuna 13 spreads over the hills surrounding the western flank of the Valley of Aburrá. It was the last area controlled by urban militias before military and paramilitary operations expelled them in 2002. Paramilitary groups then controlled this disputed territory until their demobilization (2003–2006). The failure of the demobilization process led to the reconversion of many of these former combatants into common street-gangs, generally referred to as combos who control territories ranging from a street or a plaza to a whole neighbourhood. Despite this context of persistent violence, the comuna 13 rapidly became an important showpiece of social urbanism, especially after the construction of its Metrocable in 2008. The PUI of comuna 13-San-Javier includes a brand-new library, a viaduct and the ongoing construction of a university campus, replacing a former jail for women. Concerning this last project, Santiago Uribe, the former Chief Resilience Officer of Medellin, explains: “The idea is to replace a place based on a traumatic memory [a jail] by a site oriented toward education, art and culture.” [38] Many sites of the comuna 13 illustrate this process: changing the image of a site associated with violent memories by modern constructions. Santiago Uribe describes a new youth centre built at the end of the Metrocable: “10 years ago it was still a complex rural territory. It was a farm belonging to the Ochoa family [key-player in the Medellin Cartel] and a strategic site for Pablo Escobar due to its position on the top of the hills. There was even a ‘plaza de toros’ for the mafia!” [38] Presently, the site hosts a modern swimming pool, sports installations and a multimedia centre for the youth of the neighbourhood. Similarly, some roadside sites used as dumps for dead bodies—sometimes named “devil’s curves” (curvas del diablo)—have been reinvested by sports installations or miradors. Like the case of Moravia, these transformations spiked international interest: before the pandemic, the comuna 13 was the most visited site of Medellin, with more than 160,000 visitors in 2018 [39]. The main highlight for tourists visiting the comuna 13 are the outdoor electric stairs inaugurated in 2012 and the vibrant urban art scene that sprang up around them.

4. Materials and Methods

The results presented here are part of a larger study examining the relations between urban violence, resilience and collective memory in Medellin (Colombia), New-Orleans (United-States) and Belfast (Northern Ireland). This article focuses on the case of Medellin because this city provides an opportunity to explore how ideas, such as that of “resilience”, can be integrated into branding narratives. In the context of Medellin, 64 semi-directive interviews were conducted during three months of fieldwork (2019–2020). Respondents have been classified into four categories. While the author is aware these categories are superficial and many respondents could be part of several groups simultaneously, the Table 1 and Table 2 below allow for a concise presentation of the type of actors interviewed. Category 1 encompasses actors of the civil society (community leaders, artists, members of the tourism sector, academia and NGOs, etc.); category 2 includes public authorities and international institutions (municipality, 100RC, UNDRR, Truth Commission, etc.); category 3 groups illegal actors (former and present members of paramilitary groups and gangs); and category 4 includes residents of the two comunas in the centre of this study: the comuna 13 (San Javier) and the comuna 4 (Moravia). Most of the interviews with the residents were conducted in their homes and very often other members of the household would join in the conversation.

Table 1.

Respondents of category 1,2,3—Medellin Case Study.

Table 2.

Respondents of category 4—Medellin Case Study.

As the tables below illustrate, while most of the interviews were conducted in Medellin, additional fieldwork has been undertaken in the two other main cities of the country: Bogota, the capital, and Cali, the third city of Colombia. Moreover, an interview has been realized in Mexico via a videocall and another one was conducted in Geneva, Switzerland. When working on resilience programs, the fact of living and working in Geneva provides an opportunity to interact with its important network of international organizations and NGOs.

The interview questions were related to various themes and different interview grids were conceived according to the respondent categories. However, this process required a certain level of flexibility as some respondents could belong to more than one category (e.g., a community leader is also a resident of one of the neighbourhoods under study). Accordingly, questions from diverse interview grids could be simultaneously addressed. A common part of the interview grid concerned the relation respondents had with their city and neighbourhood (e.g., important changes they observed, significant memories associated with the place, personal considerations on the development of local tourism and the transformation of the city), as well as their personal status (e.g., demographic data, personal history, local relationships). Stakeholders involved in institutions such as NGOs, government administrations or private bodies were asked detailed questions about their professional practice (e.g., their role in the organisation or the interactions they have with local communities). Residents of Moravia and the comuna 13 were specifically questioned on the context of violence they were living with (personal perception of the violence, interactions with local gangs, strategies to cope with the violence such as manoeuvring invisible borders and negotiating extortion taxes, whom they would turn to between local gangs and public authorities to resolve conflicts.) Finally, all respondents were asked to reflect on the notion of “resilience” (personal definition, potential criticisms, specific understanding of this idea in the context of Medellin or in their neighbourhood).

Interviews were mostly conducted in Spanish, although a few were realized in English and French. All the interviews were undertaken without translator and most of them were recorded and transcribed. All the material was then analysed with Atlas.ti.8 software. Additionally, a large amount of semi-participant observation was undertaken, mainly through the involvement of the author in community work (urban gardening, cultural development and memory work) and participation in local and international events (as diverse as commemorative ceremonies, international conferences on resilience or neighbourhood meetings). Finally, ongoing content analysis supported fieldwork, principally studying media content, official reports and promotion material.

5. Results

5.1. Resilience as a City Brand

“‘Resilient’ is perhaps the most beautiful and complete adjective that we can use to describe Medellín, because everything else derives from it. Medellín is an innovative, inclusive and forward-thinking city. However, all this has only been possible because of our capacity to overcome the obstacles that we have faced over time.”[40] (p. 4)

This quote from the former mayor Sergio Fajardo introduces the Medellin Resilience strategy, written after its integration into the 100RC network. Fajardo, the founder of social urbanism, mentions the two main attributes of urban resilience in Medellin: innovation and the capacity of its people to overcome obstacles. On the next page, Michael Berkowitz, who was the president of 100RC, clearly underlines the global image that resilience contributed to a city “leading the way in urban transformation and resilience for Latin America and the world. […] This strategy exemplifies the holistic and award-winning thinking that Medellin has become known for globally.” Fajardo, like Berkowitz, commented on the importance that citizens and the comunas (a reference to the peripheral neighbourhoods of Medellin) played in the construction of Medellin as a resilient city:

“The Medellin resilience team, the Mayor’s office, the City Council, and the comunas themselves have contributed to a highly integrated resilience strategy that is also reflective of the larger changes in the city.”[40] (M. Berkowitz p. 5)

“However, even in the darkest days, we never stopped believing in our city. It was thanks to the communities’ commitment that we managed to progress. The citizens embraced Medellín and transformed it.”[40] (S. Fajardo, p. 4)

The importance of resilience for Medellin, as well as its role as a global referent for resilient cities, was also emphasized by Federico Gutiérrez who was the mayor when the city was officially part of 100RC (2016–2019). He stated for instance that it “had an extraordinary history of transformation that placed it in the eyes of the world as a city innovative and resilient.” Gutiérrez highlighted this image just as tourism was starting to boom. He thus introduced the idea that tourism had a crucial role to play in the branding of a “city stigmatized by violence that would convert itself in a sustainable tourist destination.” [41].

The Municipality, through its mayors and collaborators, played a key role in branding Medellin as a resilient city (Figure 1), a narrative strongly legitimized by the participation of the city in international initiatives based on resilience, like 100RC. Medellin is also part of the C40 program based on resilience to climate change. Lina Lopez, the C40 city adviser for Medellin, highlighted the importance of participating in these programs in terms of image: “Being part of C40 brings prestige. It is rare that a mayor does not want to work with C40.” [42].

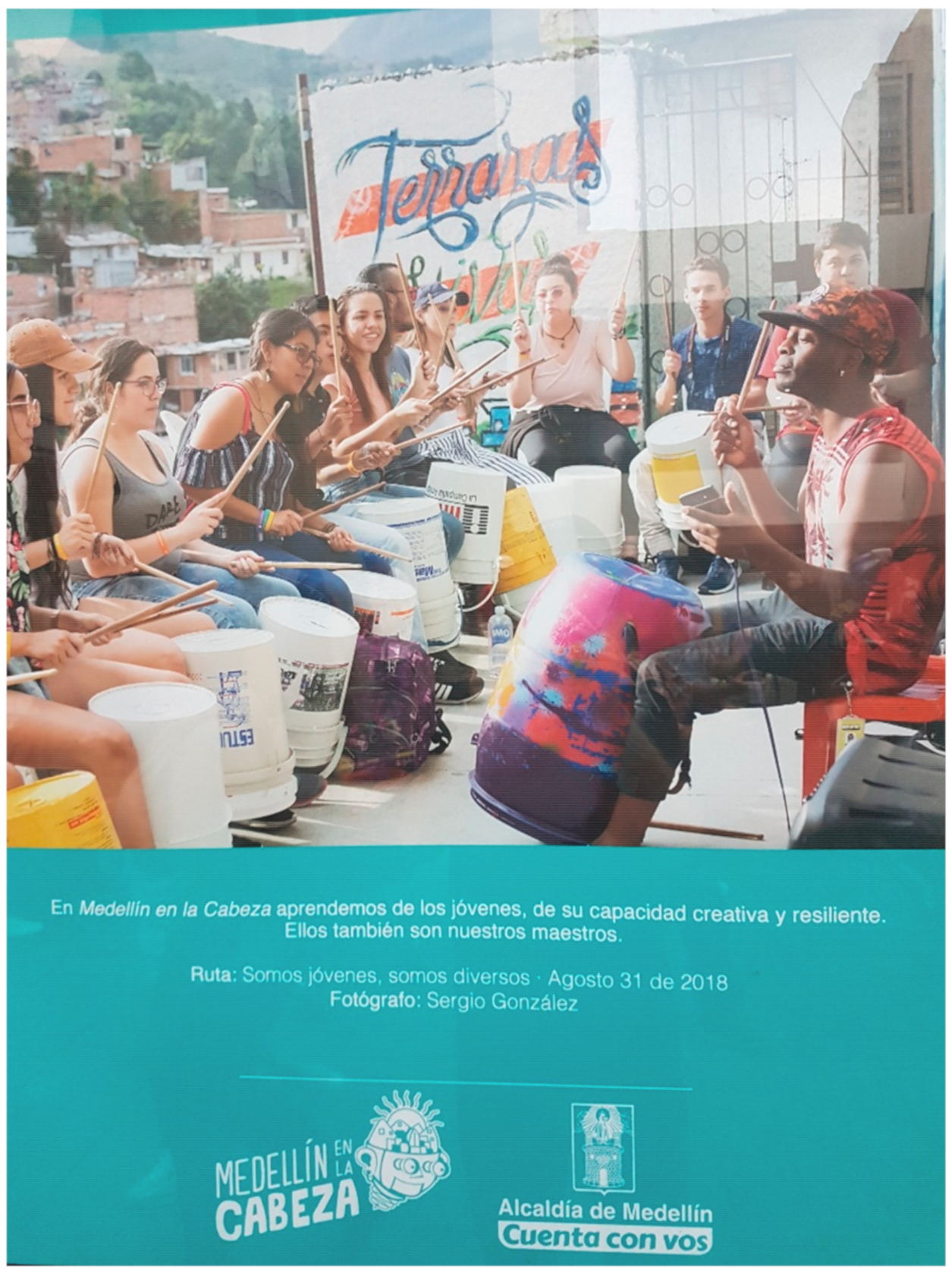

Figure 1.

A billboard installed by the municipality portraying Medellín and its youth as resilient and creative (A. Modoianu, 2018).

The image of resilience attributed to Medellin has been largely echoed on the global scene. Soon after the election of the city as a member of 100RC, national media highlighted the impact that Medellin had on the world as a laboratory for social resilience. Caracol Radio, one of the main radio networks in Colombia, stated: “Medellin was elected as a laboratory of resilience in the world to evaluate and build strategies that can be replicated in the five continents.” [43] International organizations and media similarly started to picture the city as an international reference for urban resilience and innovation. The World Bank in 2017 praised the inclusive, vibrant, and resilient city that Medellin represented for the world: “the experience of Medellin in integral urban transformation and social resilience attracts intense interest from other cities around the world.” [44].

Besides public authorities, the media and international institutions, the emergent tourism sector has also played a key role in the branding of a resilient Medellin, especially in some of its peripheral and informal neighbourhoods. Of course, this phenomenon needs to be set in the context of the global pandemic of COVID-19 which brought the burgeoning tourism sector to a brutal halt. International interest in Medellin was clearly reinforced by its involvement in various international networks such as 100RC. This was also seen as an important asset when tourism promotion was at stake. In 2020, the international platform Hosteltur highlighted the ties between the city and institutions like UNESCO, 100RC and the World Economic Forum, while describing the transformation and resilience model that Medellin represents [45]:

“This Colombian city, after decades of violence and drug-traffic, managed to change in the past few years into a model of transformation and resilience for the world. In 2019, the World Economic Forum celebrated Medellin for its high level of investment in science, technology and innovation; the UNESCO declared it ‘Learning City’. […] Medellin was also elected as one of the 100 most resilient cities in the world.”[46]

Unsurprisingly, the COVID-19 pandemic reinforced the discourse on the resilience of Medellin. Interestingly, this dynamic can be observed not only within tourism narratives but also in descriptions of tourism as such. However, the idea of “resilient tourism” appeared prior to the pandemic. In 2019 the trading platform Travel2Latam praised the resilience of travel agencies in Colombia [47], while in 2017, the Honduran regional daily La Tribuna stated:

“Tourism is important not only to promote an image, but also to encourage understanding of the capacity of the society to face crisis […] Colombia converted itself over the past few years into a referent of ‘resilient tourism’, through a focus and state politics that allowed it to overcome crisis and take advantage of the potential of this sector.”[48]

In 2020, the tourism and travel daily Expreso similarly commented that the innovation and resilience of Medellin was reflected in the tourism sector: “Medellin as an innovative city, with tourism as one its most resilient industries, will be able to face the challenges implied by new dynamics of consumption.” [49].

5.2. Resilience vs Resistance in the Tranformation of Moravia

In 2015, after it has been significantly featured in promotion discourse on urban transformation, and after community leaders saw tourism as a means to relate the history of the place and call into question past and new city developments, Moravia started to welcome its first tourists in 2015. Tourism thus offers an appropriate lens through which to observe the oppositional views of resilience in this specific part of the city. Medellin.travel, the city tourism promotion website, describes Moravia as a referent in terms of resilience, thanks to its transformation: “Actions in Moravia included the recuperation of the territory, the replanting of vegetation, the construction and maintenance of wastewater treatment plants, the consolidation of the local economy and the empowerment of social organizations. […] In total the entire intervention on the hill has benefitted more than 40,000 citizens.” [50] Many tour companies throughout the city have now integrated Moravia in their offer, adopting this positive narrative on its transformation. The Social Transformation Tour provided by Wayacan Tours is, for instance, described as follows: “Moravia is the most densely populated neighbourhood of Medellin and one of the densest in Colombia. This community is a great example of resilience and transformation.” [51].

Local community leaders in Moravia have also moved into the tourism market. Moravia Tour was launched in the last decade by twin sisters and one of their friends, all of them born and raised in the neighbourhood. The narrative of this tour is far more critical of the municipality’s plans and the transformation of the area in general. The risk of relocation for long-term residents, the destruction of the socioeconomic network, the erasure of the barrio’s memory, a lack of communication by the authorities, the architectural unsuitability of the planned buildings and even gentrification are among the criticisms put forward during their tour. As Cielo Holguín, one of the two sisters and leader of this initiative states during a visit:

“The urban renovation plan for Moravia is very bad for the neighbourhood. Moravia is not ready for such a plan because it means a ‘clean slate’ [borrón y cuenta nueva] and this is not Moravia. […] If they do an urban renovation plan here, all the social fabric will disappear... All the good of Moravia will be destroyed.”[52]

Presenting resilience merely as a part of the official branding discourse would clearly be an overstatement. Within the community of Moravia, the notion of resilience has certainly been adopted and is also part of local narratives and representations, as some murals in the neighbourhood can testify (Figure 2) Cielo herself integrates this notion in her discourses, presenting Moravia “as the only neighbourhood in Medellin with a history of resilience… It is like the phoenix that rose from the ashes.” [52] Moreover, in 2020 during the World Tourism Day, the municipality and its tourism promotion branch, the “Convention and Visitors Bureau”, awarded Moravia Tours a prize for the creativity of its offer. Mentioning the resilience of Moravia, the “Creative Tourism Network” which was co-organizing the event, praised the collaboration of the communities and the authorities: “The city of Medellín is undoubtedly a model for this new kind of tourism, if we refer to its communities’ creativity and resilience and the smart involvement and management of the City Council in fostering them.” [53] Nevertheless, as some of the examples presented above demonstrate, two opposing representations of resilience can be identified: an official one produced by the city, focusing on the transformation of the site, and a community-driven one, questioning some features of this transformation.

Figure 2.

A mural from a local artist in Moravia representing resilience.

5.3. Pride and Overtourism in Comuna 13

The internationalization and “touristification” of the comuna 13 also led to an important branding process based on resilience. This notion is featured, for instance, in the new guide on tourism and memory published by the municipality:

“Currently, Commune 13 is best known for its graffiti art, break dance choreographies, rap lyrics, electric staircases and Metrocable. This is due to the resilience of its inhabitants, which helped them overcome the stigma left behind by drug trafficking and armed groups like the guerrillas and criminal bands that settled in the territory.”[54]

Likewise, Colombia Reports, a non-profit body involved in the international promotion of the country, suggested in 2018 that the “trap” of the touristy and wealthy areas of the city should be bypassed in order to experience the “real Medellin”:

“The 13th District, or the Comuna 13, is one of Medellin’s most special places. The most western district has been most affected by the extreme violence of Colombia’s armed conflict, but has shown a resilience that is arguably unique worldwide.”[55]

Resilience is now present in the narrative of most of the tourism companies offering tours in the comuna 13, as the following examples show:

“This place was considered the most dangerous neighbourhood in the country because of the Medellin Cartel led by Pablo Escobar, the guerrillas and paramilitaries. Today, this community is an example of resilience through the arts, like music or graffiti. For example, here you will find the largest urban art gallery of Colombia, public libraries, cultural parks and the first public electric escalators of the country that connected places that were divided by the conflict.”[51]

“Comuna 13 in Medellín—A History of Resilience: The neighbourhood is a place of flourishing culture, of art, music, sport and dancing. Something that nobody would have imagined a few years back. The history of Comuna 13 is one of resilience, of the dream of the people to make their home a better one, a safer one.”[56]

“Colombia is a country of resilience, and no place embodies that attribute quite like Comuna 13.”[57]

“All guests to this area have the fortune to enjoy an outdoor urban art gallery that reflects the metamorphosis of a resilient society that does not stay in the past, but instead looks to the future with great hopes.”[58]

As mentioned above, the outdoor electric stairs of the comuna 13 now represent one of the main tourist attractions of Colombia’s second city. Commonly referred to as Las Escaleras, this site is associated with another core value also actively promoted in Medellin: sustainable mobility. Composed of 6 levels and 984 m long, Las Escaleras were initially built to improve the mobility of the approximately 12′000 residents of the comuna 13. The real impact of Las Escaleras in terms of mobility improvement sparked harsh criticism in the community, a context already well documented [7,59,60]. The main criticism is linked to the fact that this urban object contributed a lot more to the international image of Medellin than to the mobility of its residents. Following its integration into the branding of a resilient Medellin, Las Escaleras became a tourism hotspot [7]. Here again, the mention of resilience in the tourism promotion narrative is inescapable, as this advertisement on TripAdvisor demonstrates:

“Contextualized visit based in the story of the city, its resilience and social transformation. While visiting the escalators you can observe the different types of art that surround this place.”[61]

Several commentators, whether in the media or academia [59,62], have pointed to the pride that Las Escaleras has brought to the residents of the comuna 13. While this is indisputably the case to a certain extent, most recent research from the author has demonstrated that Las Escaleras as a “pride factor” [59] is far from being a homogeneous phenomenon. Some residents certainly see the electric stairs as a positive outcome that improves the image of the comuna 13, but a growing number of inhabitants expressed discomfort with the internationalization and touristification of their neighbourhood. First, with the success of Las Escaleras on the tourism and branding scene, the initial objective of improving local mobility was partly lost: Before the pandemic, Las Escalaras were mostly used by tourists and their guides. Secondly, the economic success of tourism in the comuna 13 led to the involvement from 2017 onwards of local gangs: the growing drug market targeted foreign tourists and the extortion of tour guides began. Finally, the increasing tourist market resulted in the appearance of many new tour guides, some of them with no relation to the territory, like those coming from Venezuela, Argentina and even France. Some of these guides were strongly criticized due to the many inaccuracies they related on the violence that plagued the territory. Some residents clearly expressed a feeling of dispossession of their memory and territory.

Jeihhco, a renowned hip-hop artist from the comuna 13, is one of the main actors in the development and the “touristification” of the street art around Las Escaleras. In 2010, with his colleague and graffiti artist El Perro, he created, the Grafitour to present the urban art of the area and relate stories of the violence there. As much as he considers tourism a good thing, he insists that he is more interested in giving these tours to people from neighbouring areas and those from other parts of the city. He expresses his scepticism on the real objective of Las Escaleras: “It’s not a project to transform the neighbourhood or improve the life of its residents. It is city-marketing or city-branding. And they sold it very well! It was featured in the news; it got a lot of success.” [63] After the success of this branding process and the tourism that followed, many residents started to criticize the increasing commercialization of their neighbourhood. With the development of tourism, souvenir shops, cafés and art galleries arose all around Las Escaleras and on the new viaduct overlooking them. The comuna 13 itself became a brand and is now featured on all the merchandising sold to tourists: tee-shirts, postcards, caps, mugs, etc. (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

A souvenir shop selling tee-shirts and other products with the comuna 13 brand.

For a resident who initially viewed the tours in his comuna with enthusiasm, the economic opportunities it generated distorted the practice.

“I feel it as a cool process and that it has good things, like how the people started to manage entrepreneurship… how the señora de las cremas [the ice-cream lady] manages to support her family. But I think we lost what was at its heart; it became a business to show graffiti and to make the visitor pay.”[64]

Economic prospects attracted many outsiders to work as tour guides or in other related activities. The inaccuracies of their discourse on the comuna and its history were severely criticized by many residents, as the following examples illustrate:

“You go over there, and the graffiti are very bonitos (pretty), but they do not speak to me. […] People know that this is a business, there are a fair number of foreigners, so random people [tour guides] stand there and pay the vacuna [extortion tax] telling wrong things, false histories… And they [the foreigners] take pictures and leave. This is not a site of memory.”[65]

“What do guides do? They invent stories. They are not true, but the tourists are enthusiastic. And the amount of businesses that opened! Moreover, all the drug and prostitution business takes place near Las Escaleras.”[66]

“There are people who tell lies and others who had to live through all this. Some guides greatly exaggerate things, invent them […] One had to live through many things, but some people tell a lot of mystery, too much fiction.”[67]

The impact of tourism on the image of the comuna was also pointed out by many residents. While some saw a sign of improvement in the fact that international visitors would venture into an area that was not long ago considered a no-go zone, others harshly complained about the stigma these tours helped bring to their neighbourhoods. For some residents, the guides were seen as mainly responsible for purveying “porno-miseria” or “showing the dark side of the comuna”. Others complained about the tourists themselves, commenting on the “bad reputation they would bring to the comuna”. Moreover, when Las Escaleras were built, some criticised the fact that they would only benefit a small part of the community. When tourism expanded, a similar criticism was voiced, that only residents living next to the electric stairs would enjoy the advantages of tourism. Many also argued that showing only the area around Las Escaleras gave an idealistic but distorted image of the comuna 13.

“This would be next to Las Escaleras, because here you do not see anything. They set up all the tourism over there. I say that if they are going to talk about the history of the barrio it should take into account the whole comuna.”[67]

“Even the tourists realize this. That not everything is painted pink, painted as is the comuna around Las Escaleras. That everything is lindo [beautiful]. No, not everything is lindo!”[68]

Some of the criticisms highlighted above shed some light on the relations residents have with their neighbourhood as a material space composed of streets, plazas or electric stairs, but also as a symbolic space shaped by the collective memory of the barrio, its history and all the stories associated with it. During the interviews, several respondents associated resilience with their right to their own territory or their “right to their city”. Many residents are founders or descendants of people who founded these informal neighbourhoods. However, nowadays, conflicts over land ownership are still severe between residents and the authorities who considered some housing as illegal, but also with street-gangs who often expel inhabitants from their neighbourhoods. Through a process of dispossession of the history of their neighbourhood by outsider tour guides, through the integration of their neighbourhoods into a brand they do not feel part of, through the shift of Las Escaleras from a local mobility project to an international tourist attraction, some residents, as some of the results presented above demonstrate, experience what could be considered as a loss of this right to their own city:

“What did Las Escaleras bring to us? There were people who already had a business and they had to give it up. Not everything was as bonito as they want to show it. […] So what? Did they do Las Escaleras for the barrio or for the tourists?”[69]

This last question raised by a resident was even more relevant after the beginning of the pandemic and the resulting halt of tourism in the comuna 13. As the daily paper El Tiempo noted in May 2020, the inhabitants of the comuna had to intervene with the authorities to reactivate Las Escaleras. When the pandemic started and the tourists disappeared, its operation time was reduced to only two hours in the morning, from 8 a.m. to 10 a.m. [70].

6. Discussion

The case of Medellin shows that resilience has an undeniable potential for incorporation into a city-brand. This potential lies in the elusiveness and abstraction of the notion, allowing it to fit efficiently into branding discourses. In this context, resilience is presented as an unproblematic, desirable and naturally positive feature of Medellin. However, while this conceptualization seems adequate for the branding of a city, the presentation of a unique and uniform picture of Medellin erases the many nuances and various understandings of resilience. The results presented above aim to demonstrate some of the tensions such a homogeneous vision of resilience in Medellin can create. For actors involved in the municipality and in its promotion platforms, as well as for some tourist stakeholders, the “Resilient Medellin” is embodied in its innovative initiatives, in the form of urban projects such as the Metrocable and Las Escaleras. In this context, residents on the outskirts of Medellin are pictured as resilient mainly due to their capacity to overcome the widespread violence that plagued and continues to traumatize these neighbourhoods. Yet, as the results of this study demonstrate, this positive and desirable image of resilience provokes contrasting reactions within these communities. While some residents certainly appropriate this narrative, many do not identify with this homogenous and simplified conception of resilience. The author’s previous research [71] showed that resilience in some of Medellin’s barrios populares was frequently associated with the right of these dwellers to their own city and their own territory. Their active role as founders of these informal settlements, “built by their own bare hands”, as they often point out, is seen by them as a powerful characteristic of resilience. However, many consider the role they played in the construction of their barrios as distorted or, worse, as absent from the mainstream narratives describing the transformation of Medellin. The vision of self-settled communities passively coping with violence is at odds with their active participation in the transformation of their territory. Therefore, they view some of the new urban developments of the official “Resilient Medellin”, such as the planned renovation of Moravia or the outdoor electric stairs of comuna 13, as detrimental to their right to the city, and, accordingly, to what they consider as resilience.

Previous research has shown that what was described as “Medellin’s Miracle”, its transformation from the “most violent to the most innovative city in the world”, was characterized by hegemonic and homogenizing discourses [7,60]. Samper and Marko [60] (p. 241) examine the transformation of Medellin and look at the competition between two sets of narratives: “the rhetoric and practices of the state versus that of the self-settled community members.” For these authors, the narrative of the state is largely associated with the massive urban interventions in the municipality, while that of the communities focuses on the collective memory of the barrios, notably of how they founded these neighbourhoods some sixty years ago. They argue that the narrative of the state is erasing that of the communities: “it is dangerous for state narratives to erase those of the self-settled population because, as a result, we cannot understand why Medellin’s innovations are supposed successes or failures at improving the overall quality of life.” [60] (p. 242) Ethnographic work such as the one carried out here, exploring these “erased narratives”, these “underground memories” [72], can offer a better understanding of Medellin’s transformation. Giving a voice to the communities also provides some keys to comprehension of the different understandings of resilience in Medellin. The discourse on resilience promoted by the city is mainly based on Medellin’s innovations, with some references to the capacity of self-settled communities to overcome the violence and deprivation they face. Such narratives can be problematic when they picture residents of informal neighbourhoods as “victims” struggling to adapt to a context of continuous hardship. Many others identified a more transformative type of resilience, implying community resistance based on their right to the city as founders of their barrios. They also call for structural transformations of Medellin’s economy and governance instead of constant adaptation to social inequalities. Pursuing this idea, Samper and Marko [60] (p. 262) interpret advertisements and public relations campaigns of the state as a promotion of the city as a “saviour” of Medellin’s informal settlements: “Placing the city of Medellin as the saviour has a perilous potential to render invisible the creativity, expertise and stamina of the thousands of informal dwellers who built their community in the first place.”

As presented in the theoretical framework above, an important corpus of research has similarly highlighted the tensions that competing understandings of resilience might generate, as well as the status-quo this notion might imply concerning structural issues such as inequity and poverty. In the specific context of 100RC, Weber et al., [73] look at the cases of Semarang and Jakarta, two Indonesian cities that were part of the network. They demonstrate that the “rolling out of urban resilience as a global policy” is often contested from below, mainly due to what they describe as “the hallmarks of philanthro-capitalism and neoliberal policies” driven principally by Northern institutions. The case of Durban is also enlightening as it is analysed from within by its former Chief Resilience Officer Debra Roberts and her colleagues. [74] These resilience practitioners describe how this South African city finally separated from the 100RC network due to significant conflicts triggered by the opposing ways resilience was conceived. For them, the general framing of resilience in the 100RC program did not reflect the local context of Durban. The systemic approach promoted by 100RC did not tackle the structural causes that were seen locally as undermining resilience, especially those challenges related to inequality that they saw as central in the case of Durban: “The core resilience team believed that there was ‘something missing’ in the City Resilience Framework, particularly in terms of its transformative power.[…] For example, the systemic challenge of inequality, not explicit in the City Resilience Framework, was considered central to urban resilience in a socio-institutional context like Durban”. [74] (p. 14) 100RC’s inability to address the root cause of poverty and inequity is also highlighted by Fitzgibbons & Mitchell. [75] In an analysis of 31 City Resilient Strategies, the authors also observe a general lack of inclusion of marginalized residents and a heavy concentration of cities in Northern and wealthy countries.

Like the potential transformative power of resilience mentioned by Debra Roberts, competing understandings of resilience in Medellin can be considered in terms of adaptation versus transformation. In the light of this dichotomy, the critical corpus of literature presented in the second section of this article can be enlightening, as it unveils some of the power dynamics this opposition implies. Julian Reid [26], for instance, criticizes the adaptive capacities expected from what he considers “resilient subjects of sustainable development”:

“[He] is, by definition, not a secure but an adaptive subject; adaptive in that it is capable of making those adjustments to itself which enable it to survive the hazards encountered in its exposure to the world. In this sense the resilient subject is a subject which must permanently struggle to accommodate itself to the world. Not a political subject who can conceive of changing the world, its structure and conditions of possibility, with a view to securing itself from the world”[26] (p. 74).

This vision of Reid, where “adaptive resilient subjects” do not look to the state to secure their wellbeing, somehow contradicts the criticisms of Samper and Marko who highlight discourses in Medellin in which, on the contrary, the state is presented as a “saviour”. The study presented here concludes that both conceptions are problematic. The view of marginal communities as dependent on state salvation to survive or the one where they must count on their “self-reliance” to secure their wellbeing are both open to question. Many in Medellin’s informal settlements refuse to adapt to the highly unequal conditions of their city, and at the same time contest some of the many urban developments they see as imposed by the state. By the affirmation of their right to their city, self-settled city dwellers contest this vision of constant adaptation to hardship, by demonstrating their ability to transform and act in favour of their own wellbeing. In light of these views, the state and other actors involved in the development of the city need to mobilize support for change by integrating the residents of Medellin’s barrios populares into the transformation of their city. The development of tourism in popular neighbourhoods like Moravia or those of comuna 13 offers an appropriate lens through which to look at the conflicts these competing representations of resilience can trigger. In this special issue, Lim and Lee [8] state that residents are the most crucial element in destination sustainability issues. For them, while tourists visiting an area can strengthen the pride of the residents, “over-tourism” can lead to undesirable outcomes, such as a negative perception of these same tourists. In the case of Medellin, Reimerink [59] maintains that Las Escaleras succeeded in increasing civic pride and improving Medellín’s image of modernity, but also led to new social inequalities. Her research conducted in 2014 demonstrated that the lack of participation in the conception of the project created important divergences between the planners and inhabitants. The results presented here, gathered five years later, confirm that some residents of comuna 13 have strong feelings of inequality, reflected in the idea of Reimerink when she qualifies the area around Las Escaleras as an “island of exception”.

“These ‘islands’ attracted a lot of media attention but diverted attention from the underlying problems and created new socio-spatial divides. The choice of this sophisticated intervention to solve a relatively small mobility problem was partially motivated by the policy objective to create something people could be proud of after years of neglect”[59] (p. 199).

Looking at the situation since 2019, this “proudness”, which Reimerink refers to as “the pride factor”, seems to have been seriously undermined by tourism development in the comuna 13. When the branding of the “Resilient Medellin” in areas like Moravia or the comuna 13 is examined, it sheds light on the contradictions such discourse and representations can imply. If the urban renovation of Moravia and the developments around Las Escaleras are seen as innovation and urban resilience in the narratives of some actors, such as city officials, tourism promotors and urban developers, residents can have a significantly opposing view. Finally, while it is widely acknowledged that the branding of a city reinforces its identity in a globalized world, Medellin offers a pertinent example of how this process takes place in a peripheral city. Indeed, the branding of Southern cities like Medellin strengthens their position on the global scene. Robinson called for a deconstruction of the category of what are usually considered as “global cities”, especially the (Western) standards towards which all cities should aspire [76]. In this sense, using the idea of resilience for branding purposes, a notion initially more associated with Southern and developing cities than Western and industrial ones, raises the issue of reconsidering the categorization of cities, currently taken for granted (western, third-world, African, Asian, socialist, etc.) In this new world order, Dupuis [77] (p. 49) shows that cities from the North and the South, more autonomous and interconnected, are now selecting from “a world portfolio of images and ideas to innovate in their urban design”: “These exchanges link cities from here and elsewhere, bringing some to interact, while excluding others from these networks, maps of the ‘best cities’ are being drawn up.” Urban Resilience, and especially its integration in an international program like 100RC, allows a “Southern” city like Medellin to access this world portfolio. In the new world order, resilience is thus used as a lever to situate Medellin as a global city. Furthermore, as Moncada [78] (p. 17) has shown in the case of Medellin and its past violence, city-branding appropriated negative local traits associated with the city, such as violence and insecurity, and utilized them to draw sharp contrasts with more positive local developments: “Acknowledging violence as a challenge and then contrasting it with innovative and counterintuitive policy responses, […] can draw positive international attention. And transforming the urban built environment as part of a response to violence can reshape cities to align with international perceptions of what global cities should physically approximate.” This study has demonstrated that the branding of Medellin—once the most violent to now the most innovative and resilient city in the world—was without doubt an international success. Yet, the appropriation of this branding discourse by local communities, who are themselves the focus of its set of narratives, can be interpreted quite differently.

7. Conclusions

This present analysis builds on the consensus that place branding is not just the delivery of a logo and a communications campaign. Unlike a product or a company, the branding of a city involves a great diversity of stakeholders. They belong to both the private and the public sector, and their scope of action ranges from a community level to an international level. Medellin is a pertinent case, illustrating how an abstract idea like resilience has been adopted as a city-brand. Resilience has been identified as a core-value of the city and its residents, especially those living in poor and informal settlements, and has since been promoted as an important element of Medellin’s international image. While this process was initiated by the municipality, based on the integration of Medellin into international networks like 100RC, many other actors and entities, such as the media, promotion platforms or tourist stakeholders, have also contributed to diffusing these discourses and representations. In an increasingly globalized world, international actors are now also key players in the shaping of a place’s identity. As the results above aim to demonstrate, the designation of Medellin as a flagship of resilience to urban violence in the 100RC network has significantly impacted the representations and discourses on this city. The image of a “Resilient Medellin” was promptly integrated into the burgeoning tourism sector, thus reinforcing its position as a city brand. This study also demonstrates the tensions that arise when a multi-layered notion like resilience is identified as a positive and desirable outcome, thus erasing the diverse and often competing representations it conveys. In Medellin, using resilience as a city-brand has contributed to its depoliticization. This process is considered as problematic since the “resilient communities” at the centre of these homogenizing narratives feel disconnected from the representation of their city and their neighbourhood that is being internationally publicized.

The objective here is not to dismiss the potential of resilience in international policies or imply that self-settled communities in Medellin systematically reject it. On the contrary, as has been mentioned, the notion has been adopted well beyond international and municipal actors, and many in Medellin’s barrios populares use it in their own discourses. However, current research calls for a more contextualized and integrated conceptualization of resilience, a vision of resilience that encompasses its many different interpretations. It suggests caution regarding the use of a one-size-fits-all definition of resilience as diffused by global actors like 100RC. Scholars, including geographers, anthropologists and political scientists, have a significant role to play in creating a better understanding of the triggers and limits associated with the use of resilience in international discourses on development and branding. Studies of the topic are often still based solely on content analysis of official and promotion documents. While these analyses are of paramount importance, there is a need to go beyond this approach, to offer some complementary ethnographic research looking not just at the discourses and representations of the main stakeholders involved, but also at those of the residents of these “resilient cities”. Moreover, while the present analysis offers a dive-in perspective on a particular case, more comparative studies are required to better understand the global effects of networks like 100RC, C40 or other programs implemented by international actors such as UNDRR, the World Bank or Rockefeller.

Finally, with the current pandemic, there is little doubt that notions such as “resilience”, “sustainability” or “smartness” will continue to be significantly mobilized in discourses on cities. Colombia like other countries in Latin America has been hard-hit by the health crisis and resilience will therefore certainly continue to be an important element in the narratives on Medellin and other cities of the continent. There is thus a need to reinforce critical research on resilience in Latin America to better understand the impact and objectives of initiatives centred on this notion. Many cities throughout the world have taken advantage of this global crisis to reflect on their governance and some of them have taken action to propose actual structural changes. Hopefully, Medellin can take a similar path and put resilience—and what it really means, depending on the various contexts it relates to—at the centre of these reflections. Self-settled communities should be considered as more than just passive actors who manage to endure high levels of violence and adversity; their active role in the construction of Medellin should be recognised as representing an important potential for future transformations of the city. The use of resilience in discourses on the development of cities is linked to many tangible effects, positive and negative, and it should be recognized as more than the simple construction of a catchy city-brand.

Funding

This research was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), grant number PZ00P1_179904 (program Ambizione).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anholt, S. Some important distinctions in place branding. Place Brand. 2005, 1, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M. From city marketing to city branding: Towards a theoretical framework for developing city brands. Place Brand. 2004, 1, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Ashworth, G.J. City branding: An effective assertion of identity or a transitory marketing trick? Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2005, 96, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, D.; Lloyd, G. New communicative challenges: Dundee, place branding and the reconstruction of a city image. Town Plan. Rev. 2008, 79, 507–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. On creating the ’city’ as a collective resource. Urban. Stud. 2002, 39, 1777–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naef, P. Touring the ‘comuna’: Memory and transformation in Medellin, Colombia. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2016, 16, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.-E.; Lee, H.R. Living as residents in a tourist destination: A phenomenological approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organisation. Handbook on Tourism Destination Branding; WTO: Madrid, Spain, 2009; ISBN 978-92-844-1311-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, L.A. Cooperative branding for rural destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 720–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M. Book Review: Destination branding: Creating the unique destination proposition. J. Vacat. Mark. 2004, 10, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardet, H. Creating Sustainable Cities; Green Books: Cambridge, UK, 1999; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Cassaigne, B. La ville durable. Projet 2009, 313, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, C. The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban. Innovators; Earthscan Publications: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. Cities and the Creative Class; Informa UK Limited: Colchester, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Söderström, O.; Paasche, T.; Klauser, F. Smart cities as corporate storytelling. City 2014, 18, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque-Ayala, A.; Marvin, S. Developing a critical understanding of smart urbanism? Urban. Stud. 2015, 52, 2105–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, C. Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban. Design; Penguin: London, UK, 2013; p. 400. [Google Scholar]

- Fastiggi, M.; Meerow, S.; Miller, T.R. Governing urban resilience: Organisational structures and coordination strategies in 20 North American city governments. Urban. Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, L.J.; Campanella, T.J. The Resilient City: How Modern Cities Recover from Disaster; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Reghezza-Zitt, M.; Rufat, S.; Djament-Tran, G.; Le Blanc, A.; Lhomme, S. What resilience is not: Uses and abuses. Cybergeo 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlicke, C. Resilience: A capacity and a myth: Findings from an in-depth case study in disaster management research. Nat. Hazards 2010, 67, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reghezza-Zitt, M.; Rufat, S. Résiliences: Sociétés et Territoires face à L’incertitude, aux Risques et aux Catastrophes; ISTE/Hermes Science Publishing: Cachan, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, D. The Routledge Handbook of International Resilience; Informa UK Limited: Colchester, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, J. The disastrous and politically debased subject of resilience. Dev. Dialogue 2012, 58, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Felli, R.; Soederberg, S. The World Bank’s neoliberal language of resilience. In Research in Political Economy; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2016; pp. 267–295. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, J. Resilience as embedded neoliberalism: A governmentality approach. Resilience 2013, 1, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlicke, C. The Dark Side of Resilience Exploring the Meaning of Resilience in the Context of Institutions and Power; Communication séminaire RTP CNRS: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Toubin, M.; Lhomme, S.; Diab, Y.; Serre, D.; Laganier, R. La Résilience urbaine: Un nouveau concept opérationnel vecteur de durabilité urbaine? Dév. Durable Territ. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felli, R. Adaptation et résilience: Critique de la nouvelle éthique de la politique environnementale internationale. Éthique Publique 2014, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimber, L.R. Resilience from the United Nations Standpoint: The Challenges of “Vagueness”; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- McPhearson, T.; The Rise of Resilience: Linking Resilience and Sustainability in City Planning. The Nature of Cities. Available online: https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2014/06/08/the-rise-of-resilience-linking-resilience-and-sustainability-in-city-planning/ (accessed on 8 June 2014).

- Crot, L. Planning for sustainability in non-democratic polities: The case of Masdar City. Urban. Stud. 2013, 50, 2809–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginesta, X.; De-San-Eugenio, J.; Corral-Marfil, J.-A.; Montana, J. The role of a city council in a place branding campaign: The case of Vic in Catalonia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. Le droit à la ville. L’Homme Soc. 1967, 6, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja, J. Espacio Público y Derecho a la Ciudad. Viento Sur 2011, 116, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Interviewee 6, Medellin. October 2019.

- Zapata-Aguirre, S.; López-Zapata, L.; Mejía-Alzate, M.L. Tourism development in Colombia: Between conflict and peace. Tour. Plan. Dev. Lat. Am. 2020, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Municipality of Medellin and 100 Resilient Cities. In Resilient Medellin: A Strategy for the Future; Municipality of Medellin: Medellin, Colombia, 2016.

- Somos Iberoamerica. Available online: http://www.iupac.org/dhtml_home.html (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Interviewee 12, Medellin. October 2019.

- Medellín fue elegida como laboratorio de resiliencia en el mundo. Available online: https://caracol.com.co/emisora/2017/05/31/medellin/1496229524_869131.html (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- How is Medellin a model of urban transformation and social resilience? World Bank Blogs. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/sustainablecities/how-medellin-model-urban-transformation-and-social-resilience (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Medellin has been declared a “Learning city” by the UNESCO: https://uil.unesco.org/fr/apprendre-au-long-vie/villes-apprenantes/villes-dinclusion-villes-laureates-recompense-unesco-ville; “Center for the Fourth Industrial Revolution” by the World Economic Forum: https://interestingengineering.com/medellin-becomes-a-fourth-industrial-revolution-networks-affiliate-center; and the “world’s most innovative city” by the Wall Street Journal: http://www.wsj.com/ad/cityoftheyear (All sites accessed on 6 September 2020)

- Medellín, la ciudad modelo por reinventarse tras su difícil pasado violento. Available online: https://www.hosteltur.com/comunidad/nota/023479_medellin-la-ciudad-modelo-por-reinventarse-tras-su-dificil-pasado-violento.html (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Travel Agencies, example of resilience in Colombia. Available online: https://en.travel2latam.com/nota/55801-travel-agencies-example-of-resilience-in-colombia (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Turismo y resiliencia. Available online: https://www.latribuna.hn/2017/03/24/turismo-y-resiliencia/ (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Ecoturismo en Medellín, hacia un turismo más sostenible. Available online: https://www.expreso.info/noticias/internacional/77222_ecoturismo_en_medellin_hacia_un_turismo_mas_sostenible (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Medellin.travel. Available online: https://www.medellin.travel/cerro-de-moravia-otro-ejemplo-de-transformacion-en-medellin-2/ (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Vayacan Tours. Available online: https://www.wayacantours.com/ (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Interviewee 31, Medellin. February 2020.

- Creative Tourism Network. Available online: http://www.creativetourismnetwork.org/world-day-tourism-in-medellin-creative-friendly-destination/ (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Municipality of Medellin. Tourism and Memory Guide. Heroes, Victims and Cultural Resistance; Municipality of Medellin: Medellin, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Escape the Poblado tourist trap and let the real Medellin enchant you. Available online: https://colombiareports.com/leave-poblado-to-the-provincials-and-visit-the-real-medellin/ (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Comuna 13 in Medellín—A History of Resilience. Available online: https://impulsetravel.co/tour-operator/en/blog/65/comuna-13-in-medellin-a-history-of-renilience (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Comuna 13: A Must-See Destination in Medellin. Available online: https://www.uncovercolombia.com/blog/comuna-13-traveling-medellin-colombia/ (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Comuna 13: History made Graffiti. Available online: https://bnbcolombia.com/2019/11/25/comuna-13-history-made-graffiti/ (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Reimerink, L. Planners and the pride factor: The case of the electric escalator in Medellín. Bull. Lat. Am. Res. 2017, 37, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jota, S.; Marko, T. synergies. In Housing and Belonging in Latin America, 1st ed.; Klaufus, C., Ouweneel, A., Eds.; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA; Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 241–272. [Google Scholar]

- Comuna 13. Available online: https://www.tripadvisor.com/AttractionProductReview-g297478-d19887575-Comuna_13-Medellin_Antioquia_Department.html (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Latin American Bureau. Available online: https://lab.org.uk/colombia-stairway-storytellers-in-medellin/ (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Interviewee 41, Medellin. April 2020.

- Interviewee 54, Medellin. March 2020.

- Interviewee 64, Medellin. March 2020.

- Interviewee 24, Medellin. February 2020.

- Interviewee 61, Medellin. March 2020.

- Interviewee 58, Medellin. March 2020.

- Interviewee 36, Medellin. February 2020.

- Peláez, J.B.; Con Pocas Alternativas, el Turismo Sortea su Crisis en Antioquia. El Tiempo. Available online: https://www.eltiempo.com/colombia/medellin/el-turismo-sortea-su-crisis-en-antioquia-con-pocas-alternativas-492170 (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Naef, P.; Modoianu, A. Medellin Après le Miracle: Le Droit à la Ville Créative; Gamba, F., Viana-Alzola, N., Cattacin, S., Eds.; Villes et Créativité. Seismo: Geneva-Zurich, Switzerland, 2020; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Pollak, M. Memoria, Olvido, Silencio; Ediciones Al Margen: La Plata, Argentina, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Webber, S.; Leitner, H.; Sheppard, E. Wheeling out urban resilience: Philanthrocapitalism, marketization, and local practice. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]