Transforming a Theoretical Framework to Design Cards: LEAGUE Ideation Toolkit for Game-Based Learning Design

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Challenges in the GBL Design Practice

2.2. The LEAGUE Framework

2.3. Cards as Design Tools: Useful Characteristics for Design Practice

2.4. Card-Based Tools in Various Domains

3. Toolkit Development Process: Turning the Framework into Ideation Cards

- Define goals/objectives: The following objectives were defined for the toolkit: (1) Summarize and communicate GBL design knowledge (LEAGUE framework [2] categories): making GBL concepts easily accessible to learning game designers in practice; (2) Support collaborative design process: fostering multidisciplinary focus shift by focusing on different dimensions; (3) Inspire designers: supporting the initial generation of ideas (brainstorming) by providing triggers to facilitate the creative thinking; (4) Support in-depth reflection of ideas: providing criteria to enable critical thinking and a trade-off between different aspects; and (5) Structure and guide the ideation process: orienting the ideation process from start to end with structured design activities.

- Establish target boundaries: We decided to aim for a relatively large number of cards (ultimately 176) to provide a comprehensive tool but targeted to keep the main cards (GBL concepts) to a limited number (28 in total) in order to minimize the chances of designers feeling overwhelmed.

- Scrutinize framework to extract concepts: The LEAGUE framework [2] provides the GBL design space. As described by [35], the design space is the set of decisions and choices that need to be made about the designed product, and it captures the essential elements that the design product must-have. We looked at the components of the LEAGUE framework and picked 6 key dimensions, 22 factors, and relations (see Table 1) for converting to ideation cards, as these components can fully communicate the GBL concepts required by designers to make design decisions in the learning game design process without overwhelming them with detailed sub-factors and metrics.

- Decide the type of cards: The extracted dimensions, factors, and relations were translated into a set of ideation cards. The main traits we wanted in LEAGUE cards are (i) informative and collaborative: to define and inform GBL design concepts and support multi-dimensional focus, (ii) inspirational: to support brainstorming, (iii) reflective: to support the refinement of ideas, and (iv) customizable: to facilitate the creative thinking. Therefore, we decided on four different decks of cards (primary, trigger, reflection, and custom) to focus on a particular task. In addition to the four card types, primary and trigger cards also belong to a sub-type. The two sub-types are dimensions and factors.

- Formulate the content: For primary cards, we focused on extracted dimensions and factors (see Table 1) from the LEAGUE framework [2]. The goal here was to translate the framework components into directive yet colloquial questions/tasks. For trigger cards, the goal was to provide some example answers/ideas to exemplify the possible design choices to stimulate brainstorming. Triggers were collected from ad-hoc external sources, existing educational games, and GBL literature [2,36]. For reflection cards, we focused on extracted interrelations (see Table 1) from the LEAGUE framework and translated them into critical thinking questions. The goal was to emphasize the trade-offs that need to be negotiated. Custom cards were blank cards to leave room for custom choices and support creativity. Table 2 and Table 3 illustrate the translation of framework concepts into primary and reflection cards questions.

- 6.

- Reduce items: The translation of framework dimensions and factors resulted in 28 primary cards (one question for each GBL element), and the translation of framework relations resulted in 7 reflection cards (focusing on questions that could challenge designers to reflect); thus, 35 question cards (primary and reflection cards) in total. To reach our target boundary, we limited the number of triggers (possible choices/examples) for each GBL element. This resulted in 113 examples called trigger cards.

- 7.

- Define rules/process: The LEAGUE toolkit uses structured design activities to guide the ideation process (one of the defined objectives). We defined five design activities. Each design activity had a required output and used a different set of cards and ideation sheets. We also imposed time limitations for each activity to make participants active and prevent them from being unproductive.

- 8.

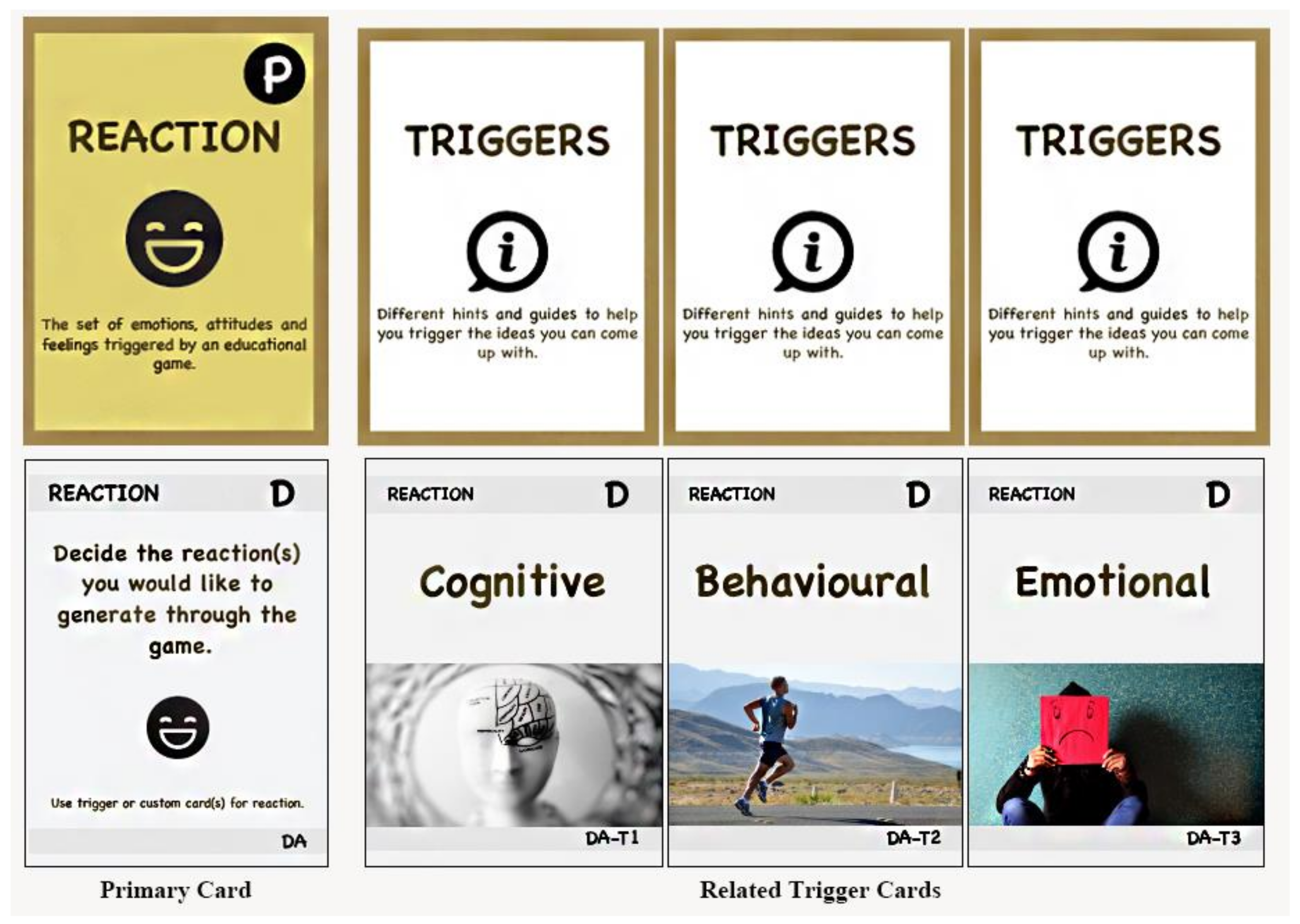

- Visualize: All cards have a standard “playing card” size approximately 2.5 × 3.5 inches (64 × 89 mm). All cards are color-coded by deck (type) and category (six dimensions) to be distinct. Figure 1 and Figure 2 shows an example of developed cards. Each of the six categories has a different color (taken from the LEAGUE framework [2]). For Trigger cards, the categories are defined by the border color of each card. All cards have a consistent graphical layout and information architecture. We made sure to keep the card design minimal and easy to follow, not overcrowded with too much text, and balance text and images [4]. The text on trigger cards (presenting example answers or triggers) is limited to only a few words, as they are intended for inspirational use and should only provide a hint and not a concrete design [4,26]. The card’s backside consists of four elements (see Figure 2): type of card deck, card title, an image icon to visualize card type, and a short description of the role of the card or the definition of the GBL-concept. The card’s frontside consists of five main elements: a unique ID, card name, the sub-type, the main question/concept/ idea, and graphics (icon or image) illustrating the question/concept/idea. However, the custom cards are blank. We also developed a board with a playbook to make the process easy to understand and structured.

- 9.

- Gather feedback: The feedback from the co-author was incorporated iteratively at each stage of the process of developing the LEAGUE toolkit. After the completion, the toolkit was discussed in detail with fellow researchers to verify that cards were understood without much explanation. They mainly provided feedback on improving the wording and presentation of cards and playboard. Afterward, the toolkit was employed in three design workshop sessions to explore the toolkit’s potential through feedback from participants and inspect the workshop session, design outcomes, and team dynamics. We used a questionnaire, focus group, observation, and video recording for the data collection.

- 10.

- Refine and improve: The toolkit was iteratively refined with feedback from fellow researchers and design workshops. In the first iteration, definitions and questions on the cards were rephrased for clarity, preciseness in meaning, and their presentation based on fellow researchers’ feedback. In the second iteration, in addition to these changes, the design activities were adjusted and re-organized by changing the allocated time and rearranging debriefing sessions based on feedback from the first workshop session. In the third iteration, we plan to improve the cards’ searchability using accessories and precisely define the criteria for reflection cards to facilitate critical thinking based on collective results from three design workshop sessions. The toolkit is not ultimate and will still be improved based on future studies.

4. The LEAGUE Ideation Toolkit: Developed Card-based Tool for GBL Design

4.1. LEAGUE Cards

- Primary Cards (Present GBL design concepts): The Primary cards are the main deck of cards that are the building blocks for GBL design. Each primary card presents one particular GBL concept. The card poses a question, or a task related to that concept, which should be discussed in a team to develop a design idea (using either custom, trigger, or any combination of these cards). The team successively answers these tasks/questions to gradually build the learning game design idea through collaborative team discussion. There are 28 primary cards in total posing 28 different tasks/questions, out of which six are primary-dimension cards (focused on framework dimensions), and twenty-two primary-factor cards (focused on framework factors).

- Trigger Cards (Support for brainstorming): Trigger cards are examples of possible design ideas or hints for primary cards’ tasks or questions. These cards trigger the thinking process by giving a direction to think. Each primary card has multiple trigger cards (with the same name as the primary cards). For example, for the primary-dimension card “reaction”, there are three different trigger-dimension cards (emotional, behavioral, and cognitive) with the same name “reaction”, as shown in Figure 3. There are 113 trigger cards in total, out of which twenty-two are trigger-dimension cards (for primary-dimension cards), and ninety-one are trigger-factor cards (for primary-factor cards). We do not claim that the trigger cards are absolute and complete. However, we believe that they cover a range of different domains and areas of the GBL design space, which are enough to trigger the brainstorming and ideation.

- Custom Cards (Allow out-of-the-box thinking): This deck consists of blank cards used by the participants to write their creative design ideas. This provides an opportunity for out-of-the-box thinking and provides room for the creative impulses of participants.

- Reflection Cards (Aid refinement of generated ideas): Reflection cards present seven evaluation criteria to reflect on the generated ideas and design choices to refine them. Each reflection card contains a question pointing to a critical relation between different GBL dimensions that can negatively impact learning games’ effectiveness if not considered. It encourages the team to critically think about the trade-off and look for design iterations if problems exist.

4.2. Design Activities

- Idea generation (Coming up with initial ideas): This activity aims to generate an initial concept for a learning game design. For this activity, the team uses sub-deck dimensions (see Section 4.1) and has six primary-dimension cards (6 dimensions), to solve using 22 trigger-dimension cards and 6 custom cards. Solving different primary cards (using trigger or custom cards) gradually generates an initial game idea. There is no right or wrong order of using the cards. Participants can shuffle through cards and pick one. The id of used primary cards is logged in the log sheet (in the order of use). The idea generation sheet is used to stick the trigger and custom cards to compose the initial idea.

- Idea development (Expanding the idea): The goal here is to expand and further develop the initial ideas from the first activity into more detailed and concrete ones. For this activity, the team uses sub-deck factors (see Section 4.1) and has 22 primary-factor cards (22 factors), to solve using 91 trigger-factor cards and 22 custom cards. The team can select and use the cards in any order. The idea development sheet is used to stick the trigger and custom cards to develop the design idea. The id of used primary cards is recorded in the log sheet in the order of use.

- Idea refinement (Reflecting on the idea): The goal is to improve or refine the developed ideas by reflecting on the design choices made using the reflection cards to identify the limitations and uncover questionable decisions. A team has seven reflection cards for this activity, and similar to the first two activities, they can shuffle through the cards and select in any order. The idea refinement sheet is used to add or replace the trigger and custom cards used to refine the developed idea. The idea refinement sheet has two sections for the placement of trigger/custom cards: one for rejected/replaced cards and one for new/added cards. In this activity, the team can use the ideation sheets from activity one and two to get an overview of design choices and stimulate reflection on what needs improvement. Both used and unused trigger and custom cards from the previous two activities can improve the design choices by discarding previously used cards and adding new adds. A log sheet is used for logging the order of the use of reflection cards.

- Idea illustration (Visualizing the game idea): This activity aims to plan the overall flow of the game in terms of how users will play the game from launching the game to quitting it. The idea illustration sheet is used to sketch the flow, and the team can choose from different ways (such as flow diagram, user scenarios, or screen prototypes) to illustrate the overall picture of a refined design idea. This activity allows for sketching the user experience and enables a transition from a static representation of ideas to a more dynamic view of how game players will play or interact with the learning game.

- Idea documentation (Archiving the final idea): This last activity aims to document the final state of the learning game design idea, producing a short version of a game design document (GDD). The idea documentation sheet is used that provides a format to fill in details of the final idea.

4.3. Board and Playbook

4.4. Workshop Technique

5. Toolkit Evaluation: The User Study

- Participants experience using the toolkit: How did participants experience learning game design using the toolkit in terms of fun, satisfaction, understandability, and usefulness?

- Roles (defined objectives) of the toolkit in the GBL design practice: Were the five defined objectives (i) inform GBL design knowledge, (ii) support collaborative design process, (iii) brainstorming, (iv) reflection, and (v) guidance for GBL ideation for the toolkit achieved?

- Refinement of the toolkit: How to further improve the toolkit?

6. Results and Analysis

6.1. Participants Experience Using the Toolkit

6.2. Roles (Defined Objectives) of the Toolkit in the GBL Design Practice

6.3. Refinement of the Toolkit

6.3.1. Challenges in the Workshop Format

6.3.2. Challenges in Working with the Cards

7. Discussion and Conclusions

7.1. Strengths of the Design Toolkit

- Easy to use in practice: The structured design activities systematically break down the creative process into individual steps that are easier to understand and operate. The cards, on the other hand, supported users to carry out the individual tasks. This is consistent with results from previous card-based tools, e.g., [15,26]. The cards helped the participants recognize that several elements combine to make an effective learning game and further helped them identify these essential elements. The team can shuffle through cards (owing to their tangible form [4,19]) to select them to cover the important aspects until they feel satisfied with their idea.

- Stimulate brainstorming and creative thinking: All participants found trigger cards useful (none disagreed) for stimulating creative thinking and as a kick start for brainstorming. They not only provided the existing ideas but also helped generate new ones. These results are in line with previous research on design cards [19,26]. Some teams would select a trigger card to elaborate on the idea with team discussion and end up combining the trigger card with a custom card to generate a new idea.

- Creative elements in the toolkit generate fun: The majority of participants considered that trigger and primary cards were more useful than the reflection cards, which can also be explained with the results for reflection activity that was considered comparatively less fun than idea generation and development (see Table 4). The fun element was led by the creativity involved in the design activities. The design activities which required more creativity were considered more fun (even if they were lengthy or less easy to understand at first) as compared to activities like reflection and illustration, which were comparatively less creative and required more critical and analytical thinking, were comparatively less fun (although they were fun for more than 60%). Lastly, the documentation activity was the least fun part, although it was the easiest to understand.

- Guide the design process in a playful manner: Cards and design activities together provided a structured path that offered guidance on how to proceed with the design process. They give a clear direction and order by providing guidelines to follow five steps (design activities) and building blocks to use (different card decks). The use of different types of cards was successful for individually supporting each design activity, introducing new elements specific to that step not only guided that activity but also added newness and individuality avoiding them to become boring. Participants were engaged in exploring new cards to achieve a new goal. Each card type was useful for their specific design task, and the card content was useful and easy to understand. Therefore, the results confirmed that the cards were useful for idea generation, development, and refinement, which is in line with the previous finding [17,26]. The majority of the participants enjoyed using the cards (74%) and thought that design activities were useful and fun (85–88%).

- Inform and encapsulate theoretical concepts: The primary cards were useful for informing and encapsulating theoretical GBL design concepts (only 9% participants disagreed). Such an assessment is similar to previous findings by [24]. The majority of the respondents (71–74%) thought that they considered elements they might have overlooked otherwise, and the information on the cards was useful. The cards’ information acts as a quick reminder for designers to the related knowledge/experience, which helps them focus on “all GBL aspects” during idea generation, development, and refinement resulting in a more concrete design. Using all six primary cards in the first activity resulted in a strong foundation, as the initial design idea comprised all six GBL aspects to expand on in the next activity. One of the participants praised the potential of the toolkit for academia: “This can be used by the teachers in the learning game design course since it explains all the important dimensions”.

7.2. Some Design Decisions that Proved Helpful

7.3. Limitations of the Study

7.4. Conclusion and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Tahir, R.; Wang, A.I. State of the art in Game Based Learning: Dimensions for Evaluating Educational Games. In Proceedings of the 11th European Conference on Games Based Learning (ECGBL 2017), Graz, Austria, 24–27 August 2015; pp. 641–650. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, R.; Wang, A.I. Codifying Game-Based Learning: The LEAGUE framework for Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 12th European Conference on Game Based Learning (ECGBL 2018), Sophia Antipolis, France, 4–5 October 2018; pp. 677–686. [Google Scholar]

- Ávila-Pesántez, D.; Rivera, L.A.; Alban, M.S. Approaches for serious game design: A systematic literature review. ASEE Comput. Educ. (CoED) J. 2017, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Antle, A.N.; Neustaedter, C. Tango cards: A card-based design tool for informing the design of tangible learning games. In Proceedings of the DIS ‘14: Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2014, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 21–25 June 2014; pp. 695–704. [Google Scholar]

- Höök, K.; Löwgren, J. Strong concepts: Intermediate-level knowledge in interaction design research. ACM Trans. Comput. Hum. Interact. (TOCHI) 2012, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, S.; Liarokapis, F. Serious games: A new paradigm for education? In Serious Games and Edutainment Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bekker, T.; De Valk, L.; Eggen, B. A toolkit for designing playful interactions: The four lenses of play. J. Ambient Intell. Smart Environ. 2014, 6, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- dos Santos, A.D.; Fraternali, P. A comparison of methodological frameworks for digital learning game design. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Games and Learning Alliance (GALA 2015), Rome, Italy, 9–11 December 2015; pp. 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hornecker, E. Creative idea exploration within the structure of a guiding framework: The card brainstorming game. In Proceedings of the TEI ‘10: Fourth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, Cambridge, MA, USA, 25–27 January 2010; pp. 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; Rahim, L.A.; Arshad, N.I. A review of educational games design frameworks: An analysis from software engineering. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Computer and Information Sciences (ICCOINS), IEEE, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 3–5 June 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Theodosiou, S.; Karasavvidis, I. Serious games design: A mapping of the problems novice game designers experience in designing games. J. e-Learn. Knowl. Soc. 2015, 11, 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, R.; Wang, A.I. Insights into Design of Educational Games: Comparative Analysis of Design Models. In Proceedings of the Future Technologies Conference (FTC) 2018, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 15–16 November 2018; pp. 1041–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; Rahim, L.A.; Arshad, N.I. An analysis of educational games design frameworks from software engineering perspective. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2015, 14, 123–151. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, I.L.; Fernandes, F. A literature review for game design frameworks towards educational purposes. Lisboa Play2Learn 2018, 321–332. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, F.; Gibbs, M.R.; Vetere, F.; Edge, D. Supporting the creative game design process with exertion cards. In Proceedings of the CHI ‘14: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014; pp. 2211–2220. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Manjón, B.; Moreno Ger, P.; Martinez-Ortiz, I.; Freire, M. Challenges of serious games. EAI Endorsed Trans. Game-Based Learn. 2015, 2, 150611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wetzel, R.; Rodden, T.; Benford, S. Developing ideation cards for mixed reality game design. Trans. Digit. Games Res. Assoc. 2017, 3, 175–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raftopoulos, M. Playful card-based tools for gamification design. In Proceedings of the OzCHI ‘15: The Annual Meeting of the Australian Special Interest Group for Computer Human Interaction, Parkville, VIC, Australia, 7–10 December 2015; pp. 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lucero, A.; Dalsgaard, P.; Halskov, K.; Buur, J. Designing with cards. In Collaboration in Creative Design; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, X.; Lu, Y.; Oinas-Kukkonen, H.; Brombacher, A. Perswedo: Introducing persuasive principles into the creative design process through a design card-set. In Proceedings of the IFIP conference on human-computer interaction, Mumbai, India, 25–29 September 2017; pp. 453–462. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; Rahim, L.A.; Arshad, N.I. Towards an Effective Modelling and Development of Educational Games with Subject-Matter: A Multi-Domain Framework. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on IT Convergence and Security (ICITCS), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 24–27 August 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Pivec, M.; Dziabenko, O.; Schinnerl, I. Aspects of game-based learning. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Knowledge Management (I-KNOW ‘03), Graz, Austria, 2–4 July 2003; pp. 216–225. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, T.; Procci, K.; Bowers, C. Serious games usability testing: How to ensure proper usability, playability, and effectiveness. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Design, User Experience, and Usability, Orlando, FL, USA, 9–14 July 2011; pp. 625–634. [Google Scholar]

- Kwok, S.Y.; Harrison, D.; Malizia, A. Designing individualisation of eco information: A conceptual framework and design toolkit. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2017, 10, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero, A.; Arrasvuori, J. PLEX Cards: A source of inspiration when designing for playfulness. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Fun and Games, Leuven, Belgium, 15–17 September 2010; pp. 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, S.; Gianni, F.; Divitini, M. Tiles: A card-based ideation toolkit for the internet of things. In Proceedings of the DIS ‘17: Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2017, Edinburgh, UK, 10–14 June 2017; pp. 587–598. [Google Scholar]

- Bekker, T.; Antle, A.N. Developmentally situated design (DSD) making theoretical knowledge accessible to designers of children’s technology. In Proceedings of the CHI ’11: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–12 May 2011; pp. 2531–2540. [Google Scholar]

- Halskov, K.; Dalsgård, P. Inspiration card workshops. In Proceedings of the DIS06: Designing Interactive Systems 2006, University Park, PA, USA, 26–28 June 2006; pp. 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kultima, A.; Alha, K. Using the VNA Ideation Game at Global Game Jam. In Proceedings of the 2011 DiGRA International Conference: Think Design Play (DiGRA ‘11), Hilversum, The Netherlands, 14–17 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kultima, A.; Niemelä, J.; Paavilainen, J.; Saarenpää, H. Designing game idea generation games. In Proceedings of the FuturePlay08: FuturePlay 2008 Academic Games Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3–5 November 2008; pp. 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Schell, J. The Art of Game Design: A Deck of Lenses; Schell Games: Burlington, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wölfel, C.; Merritt, T. Method card design dimensions: A survey of card-based design tools. In Proceedings of the 14th IFIP TC 13 International Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, 2–6 September 2013; pp. 479–486. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, E. Designing exploratory design games: A framework for participation in Participatory Design? In Proceedings of the PDC’06: Expanding Boundaries in Design, Trento, Italy, 31 July–5 August 2006; pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, M.G.; Rovelo, G.; Haesen, M.; Luyten, K.; Coninx, K. Capturing design decision rationale with decision cards. In Proceedings of the IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Mumbai, India, 25–29 September 2017; pp. 463–482. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, M. The role of design spaces. IEEE Softw. 2011, 29, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, N.E. Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive learning objectives. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. JMLA 2015, 103, 152–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014; p. 358. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Ger, P.; Burgos, D.; Martínez-Ortiz, I.; Sierra, J.L.; Fernández-Manjón, B. Educational game design for online education. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008, 24, 2530–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Conceptual Level | Elements |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | Learning, Environment, Affective-Cognitive Reactions (ACR), Game Factors, Usability, and User |

| Factors | Learning objectives, learning strategy, learning content, learning outcome, technical aspects, context, enjoyment, engagement, motivation, flow, game definition, game narrative, game mechanics, game resources, game aesthetics, gameplay, interface, learnability, satisfaction; learner profile, cognitive needs, and psychological needs |

| Interrelations | Learning (integrate) Game Factors; Game Factors (generate) ACR; Usability (address/cater) User; Usability (address/cater) Environment; Environment (map) Use; User (influence) Learning & Game factors, ACR; User (influence) Learning, Game factors, ACR |

| Framework Elements | Conceptual Level | Definition of GBL Element | Primary Card ID | Translated Primary Card Task/Question | Related Trigger Cards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning (domain) | Dimension | The learning area(s) focus in an educational game to promote and facilitate learning. | DL | Decide the learning domain for the game. | Math; Climate change; Smart city; Dance |

| Learning strategy | Factor | Pedagogical theories or approaches used to achieve learning objectives. | FL2 | What strategy should be used to enable learning through the game? | Drill and Practice; Organize; Compare/contrast; Judge |

| Interrelated Dimensions in Framework | Identified Relation | Translated Question for Reflection Cards |

|---|---|---|

| Learning & Game Factors | Integration/Balance | Are game elements (game objectives, narrative, etc.) and learning elements (learning objectives, strategy, content, etc.) well integrated into this game? |

| Game Factors & ACR | Generate | Are selected game elements (narrative, mechanics, play, etc.) effective in generating user reactions (engagement, enjoyment, etc.) in this game? |

| Aspects | Key Concepts of the Questions | Agree | Neutral | Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fun | Interacting with cards was fun | 74% | 21% | 6% |

| Fun to do different activities | 88% | 9% | 3% | |

| First activity (idea generation) | 76% | 18% | 6% | |

| Second activity (idea development) | 85% | 9% | 6% | |

| Third activity (idea refinement) | 62% | 32% | 6% | |

| Fourth activity (idea illustration) | 62% | 29% | 9% | |

| Fifth activity (idea documentation) | 47% | 35% | 18% | |

| Satisfaction | Visual design of cards | 85% | 12% | 3% |

| Time given for each activity | 41% | 32% | 26% | |

| Sequence of use-primary cards | 71% | 26% | 3% | |

| Understandability | Cards | 79% | 12% | 9% |

| First activity (idea generation) | 68% | 12% | 21% | |

| Second activity (idea development) | 88% | 9% | 3% | |

| Third activity (idea refinement) | 76% | 24% | 0% | |

| Fourth activity (idea illustration) | 82% | 18% | 0% | |

| Fifth activity (idea documentation) | 88% | 12% | 0% | |

| Usefulness | Informing GBL design concepts (Primary Cards) | 74% | 18% | 9% |

| Supporting brainstorming (Trigger Cards) | 76% | 24% | 0% | |

| Reflecting on ideas (reflection cards) | 50% | 41% | 9% | |

| Information on card | 74% | 26% | 0% | |

| Easy to ideate educational game design | 62% | 29% | 9% | |

| Process provided guidance for GBL design | 85% | 12% | 3% | |

| Considered elements I would not have without cards. | 71% | 26% | 3% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tahir, R.; Wang, A.I. Transforming a Theoretical Framework to Design Cards: LEAGUE Ideation Toolkit for Game-Based Learning Design. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8487. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208487

Tahir R, Wang AI. Transforming a Theoretical Framework to Design Cards: LEAGUE Ideation Toolkit for Game-Based Learning Design. Sustainability. 2020; 12(20):8487. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208487

Chicago/Turabian StyleTahir, Rabail, and Alf Inge Wang. 2020. "Transforming a Theoretical Framework to Design Cards: LEAGUE Ideation Toolkit for Game-Based Learning Design" Sustainability 12, no. 20: 8487. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208487

APA StyleTahir, R., & Wang, A. I. (2020). Transforming a Theoretical Framework to Design Cards: LEAGUE Ideation Toolkit for Game-Based Learning Design. Sustainability, 12(20), 8487. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208487