Gender Differences in Wage, Social Support, and Job Satisfaction of Public Sector Employees

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Gender Wage Gap

1.1.2. Social Support

1.1.3. Job Satisfaction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Research Variable

2.3. Reliability Analysis

2.4. Models and Regression Analysis for Testing Gender Differences

3. Results

3.1. Correlation Coefficients between Worker’s General Characteristics and Subjective Scores

3.2. Gender Effect on Wage

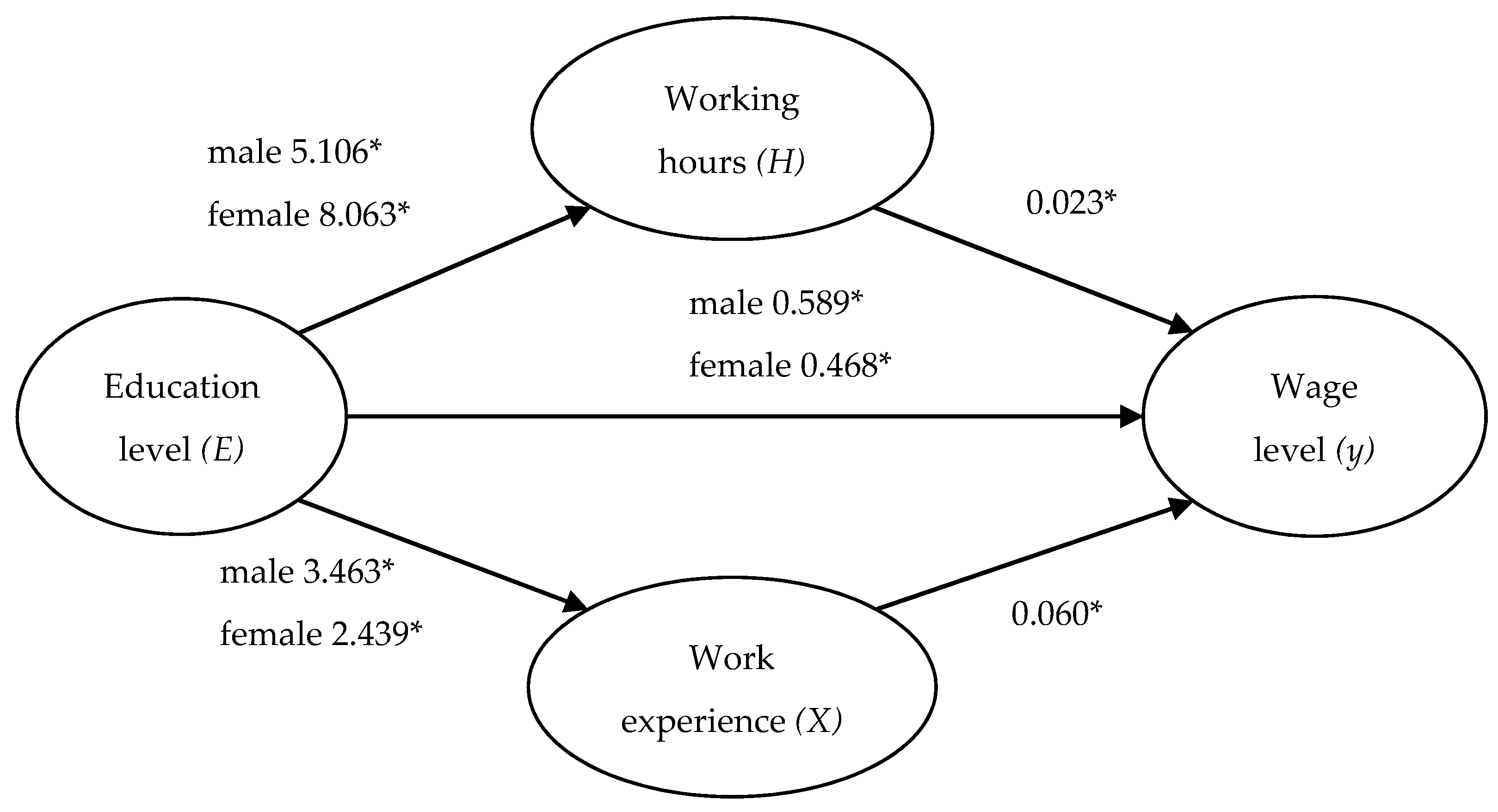

3.2.1. Effect of Education Level on Work Experience or Working Hours

3.2.2. Effect of Education Level on Wage Level

3.2.3. Effect of Education Level and Work Experience on Wage Level

3.2.4. Effect of Education Level and Working Hours on Wage Level

3.2.5. Effect of Education Level, Work Experience, and Working Hours on Wage Level

3.3. Gender Effect on Social Support

3.3.1. Effect of Education Level and Work Experience on Social Support

3.3.2. Effect of Education Level and Wage Level on Social Support

3.3.3. Effect of Education Level, Work Experience, and Wage Level on Social Support

3.4. Gender Effect on Job Satisfaction

3.4.1. Effect of Social Support on Wage Level

3.4.2. Effect of Social Support on Job Satisfaction

3.4.3. Effect of Social Support and Wage Level on Job Satisfaction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion and Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roig, R.; Aybar, C.; Pavía, J.M. Gender Inequalities and Social Sustainability. Can Modernization Diminish the Gender Gap in Political Knowledge? Sustainability 2020, 12, 3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social sustainability: A new conceptual framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bastida, M.; Pinto, L.H.; Blanco, O.A.; Márquez, C.M. Female Entrepreneurship: Can Cooperatives Contribute to Overcoming the Gender Gap? A Spanish First Step to Equality. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Núñez, R.B.C.; Bandeira, P.; Santero-Sánchez, R. Social Economy, Gender Equality at Work and the 2030 Agenda: Theory and Evidence from Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act on the Management of Public Institutions. Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=48581&lang=ENG (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Gender Jobs by Public Sector by Job Type. Available online: http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1EP_7002&conn_path=I2 (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Jang, I.S. The Problems and Improvement Plan of the Increase in Job Applicants. Labor Rev. 2019, 167, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.Y.; Park, S.Y. Influence of Job Stress Factors on Job Satisfaction among Local Officials: Mediating Effect of Depression. Korean Assoc. Local Govern. Stud. 2018, 21, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etienne, J.M.; Narcy, M. Gender Wage Differentials in the French Nonprofit and For-profit Sectors: Evidence from Quantile Regression. Ann. Econ. Stat. 2010, 99, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsdottir, I.J.; Rafnsdottir, G.L.; Ólafsdóttir, T. Job strain, gender and well-being at work: A case study of public sector line managers. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Westover, J.H. Job Satisfaction in The Public Service. Pub. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 731–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, J.A.; Nicholson-Crotty, J.; Keiser, L. Does My Boss’s Gender Matter? Explaining Job Satisfaction and Employee Turnover in the Public Sector. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 649–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlman, J. Gender differences in the impact of job mobility on earnings: The role of occupational segregation. Soc. Sci. Res. 2018, 74, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, S.E.; Juhn, C. The Rise of Female Professionals: Are Women Responding to Skill Demand? Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronberg, A.K. Workplace Gender Pay Gaps: Does Gender Matter Less the Longer Employees Stay? Work Occup. 2020, 47, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprigg, C.A.; Niven, K.; Dawson, J.; Farley, S.; Armitage, C.J. Witnessing Workplace Bullying and Employee Well-Being: A Two-Wave Field Study. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Şahin, D.S.; Özer, Ö.; Yanardağ, M.Z. Perceived social support, quality of life and satisfaction with life in elderly people. Educ. Gerontol. 2019, 45, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.M.; Tsai, B.K. Effects of Social Support on the Stress-Health Relationship: Gender Comparison among Military Personnel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Locke, E.A. The Nature and Causes of Job Satisfaction. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Dunnette, M.D., Ed.; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976; pp. 1297–1349. [Google Scholar]

- Mundia, L. Satisfaction with work-related achievements in Brunei public and private sector employees. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2019, 6, 1664191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecino, V.; Mañas, M.A.; Díaz-Fúnez, P.A.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M.; Padilla-Góngora, D.; López-Liria, R. Organisational Climate, Role Stress, and Public Employees’ Job Satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Merga, H.; Fufa, T. Impacts of working environment and benefits packages on the health professionals’ job satisfaction in selected public health facilities in eastern Ethiopia: Using principal component analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cantarelli, P.; Belardinelli, P.; Belle, N.A. Meta-Analysis of Job Satisfaction Correlates in the Public Administration Literature. Rev. Public Pers. Admin. 2016, 36, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 5th Work Condition Survey Data. Available online: http://oshri.kosha.or.kr/eoshri/resources/KWCSDownload.do (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- 6th European Working Conditions Survey (2015) Questionnaire. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/page/field_ef_documents/6th_ewcs_2015_final_source_master_questionnaire.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Korean Standard Industrial Classification. Available online: http://kssc.kostat.go.kr/ksscNew_web/ekssc/main/main.do# (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jeong, B.Y.; Park, K.S. Sex differences in anthropometry for school furniture design. Ergonomics 1990, 33, 1511–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.J.; Son, H.S. Job Stability and Job Satisfaction: Comparison between Workers in Private and Public Sector. Labor Rev. 2017, 153, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, J.Y. Policy Tasks to Reduce the Gender Wage Gap. Labor Rev. 2017, 146, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Parken, A.; Ashworth, R. From evidence to action: Applying gender mainstreaming to pay gaps in the Welsh public sector. Gender Work Organ. 2019, 26, 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wen, J.; Huang, S.; Ho, P. Emotional intelligence, emotional labor, perceived organizational support, and job satisfaction: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, A. Study on the Working Environment and Job Satisfaction of Male and Female Workers. J. Women Econ. 2019, 15, 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Pailhé, A.; Solaz, A. Is there a wage cost for employees in family-friendly workplaces? The effect of different employer policies. Gender Work Organ. 2019, 26, 688–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltzstein, A.L.; Ting, Y.; Saltzstein, G.H. Work–family balance and job satisfaction: The impact of family-friendly policies on attitudes of federal government employees. Public Adm. Rev. 2001, 61, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N.; Kretschmer, T.; Van Reenen, J. Are Family-Friendly Workplace Practices a Valuable Firm Resource? Strateg. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.Y.; Lee, H.J. Effects of the Personal and Job Characteristics, Professionalism, Organizational Commitment and Depression on the Job Satisfaction of Public Social Work Officials in Korea. Korean J. Stress Res. 2017, 25, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heo, C.U. Impact of work-life balance on job satisfaction and life satisfaction: Case of paid workers. Korea Tour. Res. Assoc. 2018, 32, 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D.S.; Park, M.H.; Jeong, B.Y. Effects of female worker’s salary and health on safety education and compliance in three sectors of the service industry. Work 2020, 65, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Variable Abbreviation: Description | Observed Score |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Z: Gender | 0: female, 1: male |

| Work experience | X: Number of years of work experience | years |

| Working hours | H: Working Hours per week | hours |

| Wage level | W: Average monthly Wage (KRW million) | 1: <100, 2: 100–200, 3: 200–300, 4: 300–400, 5: >400: |

| Education level | E: Final educational background | 1: elementary, 2: middle school, 3: high school, 4: college |

| Social support | S1: My colleagues support me. | 1: Never, 2: Rarely, 3: Sometimes, 4: Most of the time, 5: Always |

| S2: My boss helps and supports me. | ||

| S3: Respect me personally. | ||

| S4: Praise when you do a good job. | ||

| S5: Helps employees to work well together. | ||

| S6: It helps to handle things. | ||

| S7: It gives helpful feedback about work. | ||

| S8: Encourage and help you develop. | ||

| Job satisfaction | J1: At my work, I feel full of energy | 1: Never, 2: Rarely, 3: Sometimes, 4: Most of the time, 5: Always |

| J2: I am enthusiastic about my job | ||

| J3: Time flies when I am working | ||

| J4: In my opinion, I am good at my job | ||

| J5: I exhausted at the end of the working day | 1: Always, 2: Most of the time, 3: Sometimes, 4: Rarely, 5: Never | |

| J6: I doubt the importance of my work |

| Latent Variable | Initial Items | Removed Question Item | Final Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social support | 8 | S1, S2 | 6 | 0.898 |

| Job dissatisfaction | 6 | J5, J6 | 4 | 0.784 |

| Model | Dependent Variable (y) | Independent Variable | Regression Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Wage level | Z, E, X, H, E*Z, X*Z, H*Z | y = β0 + α0 Z + β1 E + β2 X + β3 H + α1 E*Z + α2 X*Z + α3 H*Z |

| Model 2 | Social support | Z, E, X, W, E*Z, X*Z, W*Z | y = β0 + α0 Z + β1 E + β2 X + β3 W + α1 E*Z + α2 X*Z + α3 W*Z |

| Model 3 | Job satisfaction | Z, W, S, W*Z, S*Z | y = β0 + α0 Z + β1 W + β2 S + α1 W*Z + α2 S*Z |

| Work Experience | Working Hours | Education Level | Wage Level | Social Support | Job Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work experience | 0.334 * | 0.343 * | 0.630 * | 0.113 * | 0.092 * | |

| Working hours | 0.620 * | 0.600 * | 0.061 * | 0.104 * | ||

| Education level | 0.660 * | 0.160 * | 0.202 * | |||

| Wage level | 0.159 * | 0.184 * | ||||

| Social support | 0.459 * |

| Dependent Variable (y) | Independent Variable | Regression Model | R2 | Model Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work experience | Z, E, E*Z | y = −0.104 + 2.439E + 1.024E*Z | 0.156 | p < 0.001 * |

| Working hours | Z, E, E*Z | y = 7.548 + 14.184Z + 8.063E − 2.957E*Z | 0.422 | p < 0.001 * |

| Wage level | Z, E, E*Z | y = 0.200 + 0.773E + 0.202E*Z | 0.499 | p < 0.001 * |

| Wage level | Z, E, X, E*Z, X*Z | y = 0.211 + 0.601E + 0.070X + 0.171E*Z − 0.012X*Z | 0.650 | p < 0.001 * |

| Wage level | Z, E, H, E*Z, H*Z | y = −0.157 + 0.563E + 0.03H + 0.176E*Z | 0.542 | p < 0.001 * |

| Wage level | Z, E, X, H, E*Z, X*Z, H*Z | y = −0.064 + 0.468E + 0.060X + 0.023H + 0.121E*Z | 0.672 | p < 0.001 * |

| Dependent Variable (y) | Independent Variable | Regression Model | R2 | Model Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social support | Z, E, X, E*Z, X*Z | y = 3.477 + 0.072B+ 0.004E | 0.029 | p < 0.001 * |

| Social support | Z, E, W, E*Z, W*Z | y = 3.479 + 0.049B + 0.045I − 0.057Z | 0.033 | p < 0.001 * |

| Social support | Z, E, X, W, E*Z, X*Z, W*Z | y = 3.479 + 0.049B + 0.045I − 0.057Z | 0.033 | p < 0.001 * |

| Dependent Variable (y) | Independent Variable | Regression Model | R2 | Model Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wage level | Z, S, S*Z | y = 1.141 + 0.405S + 1.046Z | 0.164 | p < 0.001 * |

| Job satisfaction | Z, S, S*Z | y = 1.829 + 0.468S + 0.052Z | 0.212 | p < 0.001 * |

| Job satisfaction | Z, W, S, S*Z, W*Z | y = 1.780 + 0.045W + 0.450S | 0.223 | p < 0.001 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, S.H.; Jeong, B.Y. Gender Differences in Wage, Social Support, and Job Satisfaction of Public Sector Employees. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8514. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208514

Yang SH, Jeong BY. Gender Differences in Wage, Social Support, and Job Satisfaction of Public Sector Employees. Sustainability. 2020; 12(20):8514. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208514

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Seung Hee, and Byung Yong Jeong. 2020. "Gender Differences in Wage, Social Support, and Job Satisfaction of Public Sector Employees" Sustainability 12, no. 20: 8514. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208514