1. Introduction

The continued advancements in technology have accelerated over the last few decades. Wide convergence of information systems (ISs) and information communication technology (ICT) is now an unavoidable consequence of these developments, along with an all-encompassing globalization of organizations. ISs are one of the most valuable assets of almost every global organization. Thus, efficient IS security (ISec) can be more relevant now than ever in organizational structures, and work in this field is still considered to be emerging [

1]. Despite all the advancements in security tools and protocols, hackers and hacking techniques have evolved with the rise of ICT. Behavioral and technical controls have the possibility of malicious infringements [

2], such as social engineering or denial of service attacks. IS users often disconnect between identifying a possible threat and taking the necessary steps to prevent it [

2,

3]. Nonetheless, attempts to reduce future risks will help prevent significant harm to any organization’s computing resources. A key organizational need to create a successful organizational ISec is to understand the presence and magnitude of the threat with respect to the core organizational infrastructure. For instance, critical energy infrastructures (e.g., nuclear power generation, energy sector, hydroelectric dams, electric transmission) are deemed the most vulnerable infrastructures to be protected according to the security standards [

1]. The security of these infrastructures is handled by the government or other national institutions in order to prevent any chaotic situation resulting from a successful cyber-attack attempt. The top management of such organizations understands the need for information and cyber security and enforces security with utter vigilance [

4]. An effective policy document based on international standards, in place of security education and training programs and commendable workplace capabilities, can lead these organizations towards the development of healthy information security culture [

5,

6,

7].

An important organization type with a highly vulnerable infrastructure that is often overlooked in ISec research is O&G organizations. The rising advancements in information technology and digitalization techniques in O&G organizations make them vulnerable. The adoption of technology requires greater attention to information security issues in these organizations [

8]. A recent survey indicated that almost 70 percent of O&G organizations faced at least one significant information security breach in the last decade worldwide [

9]. The Ponemon Institute report on critical infrastructure stated that the O&G industry is the most prone industry to cyber threats, and nearly 70 percent of O&G organizations compromise on information security requirements [

10]. Due to their high vulnerability, O&G organizations mainly focus on technical controls and often overlook behavioral controls [

11]. However, it is the responsibility of organizations to use multiple approaches to protect their IS assets and resources. Researchers have indicated that organizations that fail to focus on individual and other organizational issues, along with technology-based solutions, may fail to make their efforts successful [

12,

13]. Despite the enormous investments that organizations make in the provision of IS security tools, security incidents and breaches remain a major problem [

14,

15]. One of the vital reasons for continued attacks on organizations is that organizational employees are less competent in compliance with IS security, and lack of organizational governance [

16,

17]. Thus, an effective approach to mitigate IS security threats requires that O&G organizations focus on their ISec governance and employees’ intentions and behaviors towards ISec.

One of the most common methods organizations use to shape employee behavior towards ISec is enforcing security rules and regulations through a legal document called an information security policy (ISP). However, the literature suggests that, even if the ISP of an organization is in place to prevent misuse, abuse or destruction of organizational assets, its employees will still not comply [

18,

19]. A review presented by Anderson and Agarwal [

20] in this area indicated that the majority of previous ISP compliance (ISPC) research is carried out from the point of view of criminological theories—i.e., rational choice theory, protection motivation theory, general deterrence theory, and situational crime prevention theory. Although previous research efforts have advanced expertise in the field to support these perspectives, we contend that other theoretical bases may provide more insight into compliance with the ISP. Multiple researchers have argued that most organizational problems are rooted in social influence, socialization, cognition and personal beliefs. Therefore, social factors can equally influence ISP compliance and the behavioral intentions of employees [

18,

21,

22,

23]. Research focusing on penalties, sanctions or other criminological theories have accepted that IS misuse can only be deterred through punishment [

24,

25]. On the other hand, there have been new insights that challenge this view; for instance, Willison et al. [

26], Vance et al. [

27] and D’Arcy et al. [

16] showed that fear appeals and punishments not always deter non-compliance. Furthermore, these studies proved that, when employees are deterred with punishments, they may adopt neutralization techniques to minimize the effects of their organizations’ reprisals. In accordance with above arguments, this paper evaluated social bond factors to assess employee’s adherence with organizational security policy.

1.1. Research Gaps

Information system security of critical infrastructures is considered an emerging area of research. However, there are some important research gaps identified by Eirik Albrechtsen et al. [

28], which remain open in the context of behavioral information security regarding the O&G sector. The first research gap is that there are very few frameworks available for information security management for O&G organizations. However, Eirik Albrechtsen provided multiple frameworks regarding incident management for Norwegian O&G organizations, but no framework is available to assess and enhance information security policy compliance, specifically for O&G organizations. Furthermore, in a similar study, Eirik Albrechtsen et al. [

29] emphasize the need for a comprehensive investigation of information security policy compliance in O&G organizations. There are several studies which investigated O&G organizations regarding information security—for instance, H. Lu et al. [

30] have provided a review in the O&G sector regarding blockchains technology in O&G and its challenges regarding technical information security. Moreover, in their review, H. Lu et al. suggested that there must be an investigation of behavioral information security controls in O&G organizations. Likewise, T. Nguyen [

8] experimented in the O&G sector regarding the adoption of industry 4.0 and technical information security controls, and provided several solutions regarding data and security breaches in O&G organizations, and established that a lack of compliance with organizational ISP is a severe problem. The current study aims to solve this research gap to provide an effective research framework regarding behavioral information security policy compliance specifically for O&G organizations. The Second research gap also stems from Eirik Albrechtsen et al. [

28]. They have suggested several solutions regarding behavioral information security for the Norwegian O&G sector.

On the contrary, Norway is a developed country; Eirik Albrechtsen’s research only focused on the European region. Hence, findings and suggestions of their research cannot be generalized upon developing countries. Therefore, an exhaustive investigation is required to implement an ISPC framework and provide suggestions to deal with behavioral information security problems in O&G organizations in developing countries. However, multiple studies provided various suggestions and future directions towards behavioral information security of the O&G sector, most of the studies being conducted in developed countries [

28,

29,

31]. In brief, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study that attempts to address the ISPC problem for O&G organizations in developing countries.

1.2. Research Questions and Objectives

An effective ISec behavior involves the comprehensive use of technological tools and an intention to comply with the ISP of an organization [

32]. This paper discusses the problem of increased incidents of ISec due to ISP non-compliance in O&G organizations in developing countries. We specifically look at Malaysian O&G organizations as a suitable research case. Malaysia has the fourth-highest oil reserves and third-highest natural gas reserves in the South Asia region, and the oil, gas, and energy sector contributes to 20 percent of the Malaysian economy [

33]. Malaysian O&G organizations have more advanced tools and techniques than most developing countries, but their behavioral information security controls still need improvement [

34]. A study presented by Ahmed Abu-Musa [

35] elaborated on a lack of information security governance in O&G organizations of developing countries. Inadequate measures of information security governance cause a socially disoriented information security culture in O&G organizations [

36], which is the biggest reason for non-compliance of information security policy in the O&G sector. The aforementioned gaps identify pressing needs to propose and implement a comprehensive research framework consisted upon organizational governance and social bond theory in O&G organizations. In developing countries, O&G organizations’ control over the implementation of behavioral security procedures is insufficient, and a comprehensive investigation is needed to understand its association with management social influences and ISPC. This paper incorporates factors from organizational governance and social bond theory (SBT) to investigate the following research questions.

RQ1: What is the contribution of organizational governance factors in promoting the social behavior of employees in O&G organizations in developing countries?

RQ2: How well can social bond factors predict the behavioral intentions of O&G employees towards ISPC in developing countries?

The first objective of this research is to investigate the integration of organizational governance and social bonding to explain employees’ behavior in ISPC among O&G industry employees. The second objective is to provide a comprehensive research framework to enhance ISPC in O&G organizations of developing countries. Furthermore, we intend to provide advice and suggestions on the security issues raised due to employees’ non-compliance with information security policies designed by the O&G industry. Information security policy compliance has the potential of enabling O&G employees to reduce financial and reputational costs across the sector.

1.3. Research Contributions

The expected theoretical contribution of this research is providing a comprehensive framework for O&G organizations of developing countries, where the primary focus is on the organizational governance incorporating security awareness programs, security policies and procedures, and workplace capabilities to enhance social bonding among employees. It is believed that such a structure can bring information security policies compliance in the O&G sector with a noticeable reduction in security breaches. Conclusively, reduced maintenance costs of affected resources can be evidently noted with information security policies compliance. Practically, this research conforms to the requirement of national cybersecurity policy, which emphasizes the provision of information security policies in the O&G sector. This research will explore and highlight the implementation of security measures provided by O&G sector information security departments. Moreover, the dissemination of these security measures to the end-users (the employees) analyzed and reported to underscore the security issues raised. The result of this work will contribute to an understanding of the risks posed by relevant information security breaches by the negligence of employees, and poor security governance by the information security managers. It will give clear guidance on how to mitigate those risks to minimize the reputation, sensitive information, and financial loss to these societal pillars, such as public and private O&G organizations in general and employees in particular.

The paper is comprised of seven sections; the background of the research is described in

Section 2. The theoretical research framework, along with hypotheses, are illustrated in

Section 3. Research methodology, demography, and data collection are presented in

Section 4—the detailed data analysis and results elaborated in

Section 5. The discussion is elaborated in

Section 6, and the conclusions are presented in

Section 7.

2. Background

O&G is one of the most resourceful sectors of any country and contributes enormously to economic growth. O&G establishments are composed of a complex infrastructure, and many more industries depend on this sector. It serves as the backbone of any society, and there are many essential services dependent on this sector (transportation, aviation, defense, etc.); therefore, the unavailability of these services may cause more ripple effects to the whole economic landscape of the country [

37]. Due to the increasing need for data management and system integration, computers and ISs have become necessities for critical infrastructures (CIs). The rise of digitalization in O&G organizations has also increased information security risks [

30].

According to “BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019”, published by British Petroleum (BP), the O&G sector accounts for 57% of total energy consumption. The BP Review further predicted that O&G consumption will increase continuously, which may cause disruption in the petroleum supply. Many other reports have suggested the increased role of information technology (IT) in the O&G industry to achieve more productivity [

38,

39]. The use of IT in the O&G industry has increased rapidly over the past decade, as shown by the adoption of modern marine digital platforms, intelligent drilling and smart reservoir prediction technologies. Although the O&G industry is rapidly moving towards digitization and automation, the management and governance infrastructure of the O&G industry still follows the old framework, which has a tendency towards high cost, low efficiency, high risk and long periods. The O&G industry, therefore, faces many risks, including internal, external, physical, reputational, and cybersecurity risks. The world statistics shows that, from 2015 to 2018, nearly three-quarters of O&G organizations faced at least one cyber-attack [

9]. For attackers and hackers, many vulnerabilities are found in the structure of O&G organizations. O&G organizations have very complex production processes and operating systems. A small disruption in IT and operation technology (OT) can cause very large financial and reputational losses to O&G organizations [

30].

O&G organizations need to pay more attention to controlling human-security breaches to achieve effective system information security [

37]. It has been noted that O&G organizations suffer from heavy security breaches not due to technological errors but due to an inefficient security culture, a lack of security awareness, and poor security management practices within the organization [

40]. According to a report published in the United Kingdom [

41]

, technology-related errors account for 5% of security breaches, while 95% of breaches are related to the inefficient security awareness of people. Ahmad Abu-Musa [

35] investigated various O&G organizations’ information security governance. The IT policies of these organizations involved different ISec standards, including the American Petroleum Institute (API), Control Objectives for Information and Related Technologies (COBIT), International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) (ISO/IEC 27001) standards. However, very few O&G organizations had any information security framework to address security threats.

The purpose of this paper is to investigate ISPC in Malaysian O&G organizations. It mainly focuses on enhancements of information security policies and compliance in existing O&G organizations. ISs have been installed in Malaysian O&G organizations since the late 1990s. Since then, different government and private organizations have been utilizing ISs for different purposes. ISs are multipurpose systems that hold records of employees, allow for the management of organization staff, and perform administrative tasks. Due to the ease of system accessibility, such systems can be vulnerable [

42,

43]. Major data security breaches are noted due to a lack of employee knowledge of information security policies of the organization, which in turn cause poor compliance. Human factors contribute to a large number of security breaches in O&G ISs, due to unawareness and negligence towards the policies of the system, according to national surveys [

44,

45]. Deviant behavior of employees is the greatest threat to O&G organizations identified by researchers. One such study is [

11], which sheds light on the reasons for such behavior. To establish a comprehensive information security program, all individuals must understand the importance of ensuring the security of the enterprise and how to maintain the confidentiality and integrity of sensitive information in O&G ISs [

29]. Some studies have emphasized reasons for security breaches in O&G ISs. However, few researchers have discussed the roles of organizational governance, social bonding of employees, and the lack of ISPC in major security breaches.

3. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

Researchers have shown that the attitude of an employee depends upon the perceived motivation and feelings from society, friends, and family and has a strong effect on the intention to comply with ISP. Several research frameworks have been proposed in the literature to highlight ISP and compliance [

26,

27,

28]. Various theories have predicted employees’ attitudes towards ISPC, but implementing this complex framework in an unpredicted environment, such as the O&G industry, is nearly unattainable and infeasible. A simple and effective research model is required for accessing O&G employees. When a large enterprise is selected for ISPC, the first step is to comprehend organizational governance, which can enforce the need for ISPC. Organizational governance, also known as institutional governance, is responsible for enhancing security culture in an organization. ISP and compliance management, training, and education of security and awareness programs are believed to develop progressive security culture within organizations [

28,

46].

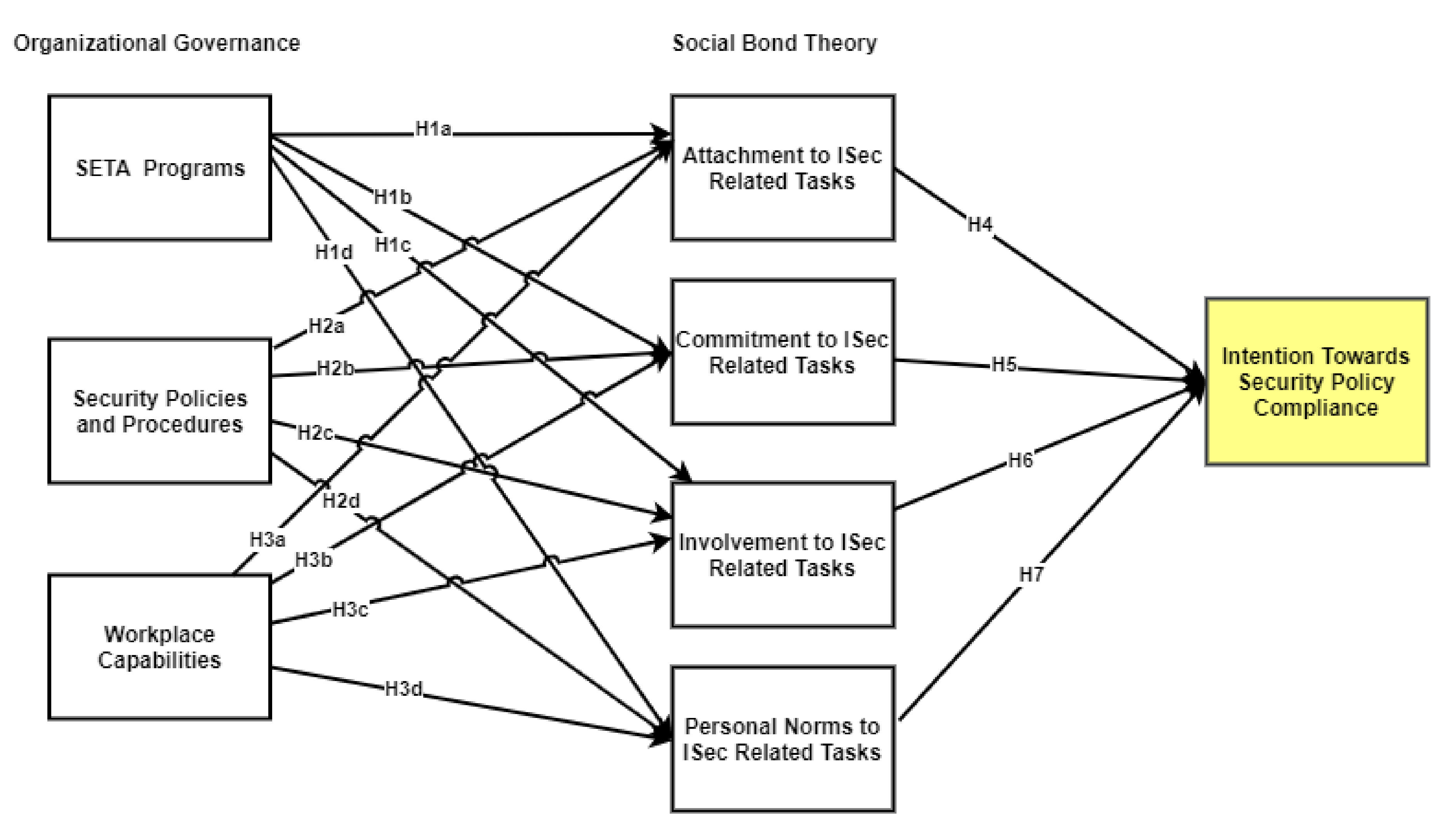

Through the consolidation of multiple theories, this research investigates the relationship of social bond theory (SBT) and organizational governance (security education, training and awareness programs, workplace capabilities, and security policies and procedures) to increase the understanding of ISPC in the O&G sector. This paper is focused on significant factors to ensure compliance with ISPs within O&G organizations. A detailed model is designed for this research to explain the hypothesized phenomenon (shown in

Figure 1). Parameters from proven social bond theory studies are integrated with three governance features—i.e., security education and training programs (SETA) [

5], security policies, and procedures (SPP) [

46,

47], and workplace capabilities (WPC) [

6,

48,

49].

3.1. Organizational Governance and its Components

Organizational Governance is a multidimensional construct that includes a set of properties that directly or indirectly affect the attitudes of employees [

50]. Organizational governance has been shown to have a substantial impact on employees’ motivation to achieve work outcomes [

8]. Because of the complex nature of organizational governance, it includes multiple factors that have significant effects on employees’ behavior, such as training, trust, support, reward, innovation, cohesiveness, and work environment. This paper focuses on three constructs of organizational governance (SETA, SPP, and WPC); each construct has its own proved significance and importance towards O&G organizations.

3.1.1. Security Education and Training (SETA) Programs

Information security awareness is defined as the employees’ general understanding of the security policy compliance, but the ISP awareness can be understood as a specific understanding of the policy of any employee [

51]. Nevertheless, to achieve security policy awareness effectively, it is necessary to use rich but compelling textual and visual material. According to research, media involvement has a significant and positive effect on information security compliance [

52]. An online awareness program is also an effective way to bring more users together and learn more synchronously about compliance. Another study proved with an experimental approach that the direct and indirect role of an employee’s information security awareness significantly affects overall organizational security culture [

53]. Hence, regular awareness programs among focused groups can bring a powerful impact on the security awareness of employees. There are many more ways to provide training and awareness to employees, such as dialogue, online programs, and video lectures. O&G companies are high revenue and less protected organizations. Most of the employees are not well addressed and are motivated towards protecting their companies’ [

37]. Research shows the existence of security policy, and its awareness, plays a vital role in organizations. Reportedly studies show that the lack of awareness on threat management and policy compliance causes more trouble than anything else. In a similar study, the researcher suggested the SETA programs to be a part of risk assessment strategies in Energy sector in order to promote the information security culture [

54]. SETA programs include effective training programs for information security among employees and have proven very useful to enhance social bonding among employees [

17,

51]. Hence, this paper’s hypotheses are as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1a). SETA programs have positive effects on employees’ attachment to ISec-related tasks.

Hypothesis 1 (H1b). SETA programs have positive effects on employees’ commitment to ISec-related tasks.

Hypothesis 1 (H1c). SETA programs have positive effects on employees’ involvement to perform ISec-related tasks.

Hypothesis 1 (H1d). SETA programs have positive effects on the employees’ personal norms towards ISec-related tasks.

3.1.2. Security Policy and Procedures (SPP)

The information security policy document is regarded as the most crucial document in the implementation of information security in organizations. The information security policy document generally follows the ISO 27,001 and ISO 27,002 Standards, which are carved according to the organizational business objectives. The alignment of the organizational plans with security policy is an essential part of information security management. Abu Musa et al. elaborated that most of the O&G organizations in developing countries do not have any information security policy. Furthermore, the majority of the O&G employees do not have knowledge about their organizations’ ISP [

35]. Multiple studies have proven that organizations with appropriate security policies and in-line security procedures can enhance social bonding among employees [

6,

17,

46]. Hence, this paper hypothesizes the following:

Hypothesis 2 (H2a). SPP have positive effects on employees’ attachment to ISec-related tasks.

Hypothesis 2 (H2b). SPP have positive effects on employees’ commitment to ISec-related tasks.

Hypothesis 2 (H2c). SPP have positive effects on employees’ involvement in performing ISec-related tasks.

Hypothesis 2 (H2d). SPP have positive effects on employees’ personal norms towards ISec-related tasks.

3.1.3. Workplace Capabilities (WPC)

WPC are extrinsic but effective factors that influence employees’ behavior. WPC include a set of sub-factors, such as the usability of systems, employee turnover, reliance on temporary employees, competency of employees, the effectiveness of monitoring procedures, job satisfaction, task pressure, task significance, security practices, disciplinary procedure, security monitoring, supervision, performance and rewards [

48,

55,

56]. Research showed that O&G organizations have better technical security controls in the workplace but lack behavioral controls [

30]. Da Veiga et al. proved that effective workplace capabilities, such as justice among employees, motivation training, rewards, and effective leadership, enhance the social environment in organizations [

6]. Hence, this paper hypothesizes the following:

Hypothesis 3 (H3a). WPC have positive effects on employees’ attachment to ISec-related tasks.

Hypothesis 3 (H3b). WPC have positive effects on employees’ commitment to ISec-related tasks.

Hypothesis 3 (H3c). WPC have positive effects on employees’ involvement in ISec-related tasks.

Hypothesis 3 (H3d). WPC have positive effects on employees’ personal norms in performing ISec-related tasks.

3.2. Social Bond Theory (SBT)

SBT was originally proposed by Travis Hirschi in 1969, and social control theory arose thereafter. SBT is an interesting way to describe the social problems of individuals. Before using SBT, one must understand the core definition of SBT as defined by Hirschi in 1969: “Components of social bonding include an attachment to families, commitment to social norms and institutions (school, employment), involvement in activities, and the belief that these things are important” [

57]. SBT, derived from the general theory of crime, states that crime occurs when an individual’s social bond is weak. This theory explains social values and social bonds between individuals, their social values and understanding of something, their attachment towards their peers, their involvement in their work, their commitment to their goals, and their beliefs in common values of the society [

46]. SBT has four major components: attachment, commitment, involvement, and personal norms [

58] as defined in

Table 1. There are plenty of research studies that have tested SBT in the context of ISPC and defined these four components in the context of ISPC as follows:

3.2.1. Attachment (ATC)

Attachment is defined as an affective component of social bond theory. Attachment, in an organizational context, means respect and affection perceived by an individual with their co-workers. Supervisors, managers and peers can be co-workers in an organizational context. The greater an individual’s attachment to his or her firm or company is, the less likely the individual will deviate from the organization’s policies, and vice versa [

36,

46,

59]. Employees care about their recognition by their supervisors, team members, or peers. Moreover, supervisors are responsible for their evaluation and promotion; therefore, attachment with supervisors or management of the organization positively affects individual security behavior. Hence, this study hypotheses the following:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Attachment to ISec-related tasks positively influences intention towards ISPC.

3.2.2. Commitment (CT)

Humans are the primary source of controlling behavioral information security; therefore, individuals’ commitment towards safeguard information security assets plays a vital role in this regard [

46] commitment can be defined as an individual’s aspiration towards his career goals. Personal achievement is an essential factor for committed persons [

60]. Committed individuals spend extra time and energy to achieve success in their careers. They would not take the risk of breaking the rules that could, therefore, harm to their careers. Consequently, studies have suggested that employees with better commitment towards their jobs are less likely to violate organizational policies [

36,

46].

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Commitment to ISec-related tasks positively influences intention towards ISPC.

3.2.3. Involvement (INV)

Travis Hirschi (1969) described that isolation is bad for the psychological growth of an individual. An employee’s involvement in social groups with his or her colleagues is a measure of their involvement in organizational policies [

36,

46,

61]. Such involvement with colleagues, organizational activities, and peers guarantees a successful business [

62]. Studies presented by Safa et al. and Lee et al. that used similar concepts proved that employees with better involvement with their organizations’ ISs issues positively influenced intention towards ISPC [

46,

63]. Thus,

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Involvement with ISec-related tasks positively influences intention towards ISPC.

3.2.4. Personal Norms (PN)

Personal norms can be defined as an employee’s values and views about organizational information security policy compliance. Lee et al. investigated the importance and role of personal norms in compliance with the ISP of an organization. Lee et al. briefly explained that personal norms affects an individual’s misbehavior towards organizational ISPs [

63]. Safa et al. also proved that personal norms significantly affect employees’ attitudes towards compliance of ISPs [

46]. Therefore, it is concluded that employees with better and favorable personal norms are more likely to comply with organizational information security policy [

36,

46]. Thus,

Hypothesis 7 (H7). Personal norms with regard to ISec-related tasks positively influence intention towards ISPC.

4. Research Methodology

This paper follows a mixed-method research design (illustrated in

Figure 2). In this paper, the researcher uses both qualitative and quantitative data collection techniques and analysis in a sequential way (qual → QUAN) but different weights [

64]. In this study, the qualitative method has less weight over the quantitative method. In the qualitative method, semi-structured interviews were conducted to better understand the problem. The result of the qualitative method helps to improve the quantitative instrument used for data collection. The mixed-methods approach is specifically useful in the context of O&G to better understand the research problem, and research findings can be inferenced and trusted [

65]. The semi-structured interview at an exploratory stage helps researchers to excavate the critical issue before using a questionnaire to collect descriptive data.

4.1. Qualitative Study

A qualitative study was performed with the help of semi-structured interviews with O&G professionals to obtain a better understanding of their general perception of ISPs. Semi-structured interviews were conducted in the Malaysian O&G sector. A qualitative study was also performed to assess the currently adopted standards of information security in the O&G industry. Interpretation of information security familiarity among managers and professionals helped us to develop a convenient research instrument. Questions for the questionnaire were adapted from the previous literature, and some of the questions were shortened according to the study requirements. Experts were approached to receive their initial opinions on the semantics and consistency of the scale items.

4.2. Pilot Study

Based on the qualitative study, a questionnaire was developed and distributed via email among the operational and office staff of 5 private and public O&G organizations in Malaysia to collect the data. From the sent emails, a total of 63 responses were collected. The purpose of the pilot test was to evaluate the validity and reliability of constructs and to refine the questionnaire for the final study. From the 63 responses, there were more male respondents than female respondents. Both private and public employees responded adequately, and all the responses were from highly experienced employees in the O&G sector. Moreover, daily computer usage was recorded because of the diverse backgrounds and departments of the study participants. From the received responses, between 4 h and 12 h of daily computer usage was recorded. ISP familiarity was also acquired from the respondents. Most of the respondents knew that their organizations had information security measures and policies, but many of them did not have in-depth knowledge of the content.

4.3. Sampling Procedure and Sampling Size

The sampled population for this research paper was executives/managers working in public and private O&G organizations in Malaysia. According to the report of the Malaysian O&G Service Council (MOGSC), there are 435 registered companies [

66]. The MOGSC categorized these companies into product and service companies. It was impractical to obtain responses from all employees. Therefore, to generalize the findings, we extracted the sample from the population through [

67].

For this research, we gathered data from both O&G product and service sectors where most executives/managers performed their duties. It was not feasible to approach all managers working in all of the industry. Therefore, the managers and executives were chosen by simple random sampling. We focused on departments that frequently interact with humans and computers. For this study, we selected 150 companies out of 435. These 150 companies have a higher market share in the Malaysian O&G sector. The sample size was justified based on certain research heuristics, such as the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Data ranging between 200 and 400 were considered sufficient for analysis [

68].

Due to the resources and time constraints, it was not feasible to approach all managers in the 150 companies. Therefore, we gathered the data using self-administered questionnaires. This study utilized the direct survey approach and electronic mail (email) methods for data collection. The targeted respondents for this study were executives and managers who have frequent interactions with both humans and computers. The complete list and email addresses of target respondents were acquired from the concerned HR department. Initially, the response rate was not encouraging; only 120 usable questionnaires were received. Then, a second email reminder was sent to the respondents. As a result, 260 responses were collected, of which 6 responses were excluded because they were ineligible. We used IBM SPSS-23 for the initial statistical analysis and SmartPLS 3 for SEM technique.

To measure non-response bias, wave analysis was applied [

69]. In this method, early response (wave-1) and late response (wave-2) were compared using the

t-test with

p > 0.05 between these two waves. The results indicated that there was no response bias in the data.

4.4. Measure

This is a survey-based research paper, and in this perspective, a questionnaire was adapted and measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree”. Organization governance has three sub-constructs: SETA programs, workplace capabilities, and security policies and procedures. The SETA program was measured by five items developed by [

17,

70]. Workplace capabilities were measured by [

48,

56]. Security policies and procedures were measured by five items, developed by [

17,

70].

The SBT has four sub-constructs: attachment, commitment, involvement, and personal norms. The attachment was measured by four items developed by [

46]. The commitment was measured by four items developed by [

23,

36]. Involvement was measured by four items developed by [

53]. Personal norms were measured by four items developed by [

22,

36]. The intention of security policy compliance was measured by four items developed by [

17].

5. Data Analysis and Results

Before analyzing the descriptive statistics, missing values and outliers were checked. There was no missing value in the data. The multivariate normality of data was analyzed employing the Mahalanobis distance (D

2) [

71]. The probability of each case by the Mahalanobis distance (D

2) was more significant than 0.001, and the score of univariates was smaller than 3 [

71]. After multivariate normality analysis, descriptive analysis tests were performed, followed by demographic analysis and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Furthermore, the construct, convergent, and discriminant validity tests were executed. Finally, the hypotheses were tested.

5.1. Descriptive Analysis

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the constructs.

Table 2 measures the central tendency (mean), dispersion (standard deviation) and symmetry of 254 observations. The mean values of all constructs are positive and center around 4. The participants of this research study responded positively to organizational governance (SETA, SPP and WPC), SBT (ATC, COM, INV and PN), and ISPC. All the values of standard deviation are positive. The higher values in

Table 2 indicated that there is a greater spread of data. Data symmetry is usually described through skewness and kurtosis. The values of all the constructs are negatively skewed. The kurtosis values indicated the degree of the peak of a distribution. The distribution of SETA, ATC, COM, INV, and ISPC is greater than zero, which means that distribution has heavier tails (leptokurtic). WPC and PN have less than zero values, which means that distribution is light tails (platykurtic)

Table 3 presents the demographic statistics used in this research. The results indicated that 36% of the respondents belong to 20–30 age categories. Moreover, 53% of the managers completed an undergraduate degree and preferred working in public organizations (63%). The results also indicated that managers with 1 to 5 years of experience are more participative than other age groups. A large proportion is aware of security policy (77%) and information and communications technology competency (56%).

5.2. Robustness of The Model

To examine the robustness of the model, the effect of control variables (age, experience, daily computer usage, etc.) on ISPC, a one-way ANOVA was used. An ANOVA is used to compare the mean of three or more groups [

72]. The principle reason for conducting a one-way ANOVA is to examine the group means difference [

73]. In this study, ISPC is a dependent variable measured on the continuous scale and is normally distributed.

A one-way ANOVA test was conducted to analyze the effect of age on ISPC. Respondents were divided into four groups. A significant difference was found between respondents’ age and ISPC score F (3250) = 13.212, p = 0.028. The effect size calculated using eta square was 0.13, which was a medium effect (Cohen, 1988). Post hoc comparisons using Tukey–HSD test revealed that the mean score of the “20–30” age group (M = 3.58, SD = 0.85) was significantly different from the mean score of the “31–40” age group (M = 4.08, SD = 0.54). Furthermore, the mean score of the “41–50” age group (M = 4.17, SD = 0.63) was significantly different from the mean score of the “51–60” age group (M = 4.25, SD = 0.67).

A one-way ANOVA test was conducted to analyze the effect of years of experience on ISPC. Respondent’s years of experience were divided into four groups. There was a significant difference found between respondents’ years of experience and ISPC score (F (3250) = 7.687, p = 0.00). The effect size of 0.08 was calculated using eta square, which was a medium effect (Cohen, 1988). Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey–HSD test depicted that the mean score of “1–5” years of experience (M = 3.80, SD = 0.86) was significantly different from “16–25” years of experience (M = 4.47, SD = 0.45). Furthermore, the mean score of “6–15” years of experience (M = 3.88, SD = 0.53) was significantly different from “16–25” years of experience (M = 4.47, SD = 0.45).

A one-way ANOVA test was conducted to analyze the effect of daily computer usage on ISPC. Respondent’s daily computer usage was divided into three groups. A significant difference was found between respondents’ daily computer usage and ISPC score (F (2251) = 4.256, p = 0.01). The effect size of 0.03 was calculated using eta square, indicating a medium effect (Cohen, 1988). Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey–HSD test revealed that the mean score of “1–5” years of experience (M = 3.80, SD = 0.86) was significantly different from the mean score of “16–25” years of experience (M = 4.47, SD = 0.45). Furthermore, the mean score of “6–15” years of experience (M = 3.88, SD = 0.53) was significantly different from the mean score of “16–25” years of experience (M = 4.47, SD = 0.45).

The empirical results depicted that sector (public and private) does not have a significant effect on ISPC (F (2251) = 2.124, p = 0.08). The ISPs existence is categorized into “yes”, “no” and “I don’t know”, and the empirical analysis demonstrates that the existence of ISPs has no impact on ISPC (F (2251) = 1.890, p = 0.17). The awareness of ISPs is divided into “not aware”, “somewhat aware” and “very much aware”. The empirical outcome demonstrates that awareness of ISPs has no significant effect on ISPC (F (2251) = 1.520, p = 0.27). From all of the study control variables, only age, experience, and daily computer usage were shown to have a significant effect on ISPC.

5.3. Assessment of the Measurement Model

In this research, partial least squares (PLS) is used to measure the model by employing SmartPLS. PLS path modeling has two sets of the linear equation; measurement model (outer) and structural model (inner). This assessment of the measurement model was further sub-divided into convergent validity and discriminant validity. The measurement model specifies the association between constructs and their observed indicators [

68].

5.3.1. Convergent Validity

Initially, the measurement model was assessed in terms of the factor loading, reliability, and validity of constructs. The obtained values for all constructs are presented in

Table 4. The values of all indicators should meet the corresponding threshold value. A variance inflation factor (VIF) that exceeds 5 indicates the presence of collinearity issues. Furthermore, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient reflects internal consistency and is recommended to exceed the minimum threshold value of 0.70 [

56]. On the other hand, composite reliability is determined based on consistent loading with the minimum threshold value of 0.70 [

57]. The value of the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct that exceeds 0.05 reflects the appropriateness of the construct.

The internal consistency via Cronbach’s alpha and the composite reliabilities were subsequently measured. Since the values of the reliability coefficients of all constructs are above 0.70, the items are reliable for their perspective measures. In addition, the reliability of the eight study constructs was assessed using Joreskog’s rho. According to Chin (1998), the threshold value of rho should be greater than 0.70. Chin (1998) considered rho as a better reliability measure than Cronbach’s Alpha for SEM. It is based on loading rather than correlations.

Table 4 also demonstrates that the AVE values of all constructs are greater than 0.5, indicating adequate convergent validity [

74,

75].

5.3.2. Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity reflects the statistical and theoretical differences of every pair of constructs involved [

76]. An accurate assessment is critical since each construct should capture a phenomenon uniquely from the empirical aspects [

77]. There are three criteria to measure discriminant validity, namely, the Fornell–Larcker criterion, the heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT), and cross-loading. Unlike the other criteria, HTMT is more precise [

76]. A value of < 1 for HTMT is considered to be good [

76]. The value of HTMT is less than 1 for all constructs.

Table 5 demonstrates the discriminant validity, and all constructs meet the threshold limit.

5.4. Assessment of the Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

5.4.1. Goodness-of-Fit Index

To verify that the model sufficiently explains the empirical data, the Goodness-of-Fit (GoF) index was applied. GoF is the geometric mean of the average R

2 and average communality [

61]. The value of GoF lies between 0 and 1, where small (0.10), medium (0.25), and large (0.36) indicate the global validation of the path model [

62]. However, the absolute application of any measure of fit remains to be fully developed [

50].

The average values were calculated and are shown in

Table 6. Notably, the GoF index value is 0.2834 and demonstrates that the empirical data fit the model satisfactorily, achieving a model with substantial predictive power in comparison with baseline values.

5.4.2. Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR)

The SRMR index is the only approximate model fit criterion implemented in PLS path modeling. It measures the estimated model fit. A threshold value of SRMR ≤ 0.08 indicates that the model has a good fit [

76], whereas an SRMR value less than 0.05 indicates an acceptable fit [

78]. The hypotheses were analyzed using SmartPLS 3. According to [

79], the measures of hypothesis testing involve the basic acceptance or rejection criteria based on the values of R

2, beta, and the corresponding t-value via a bootstrapping procedure with a resample size of 4999 [

76].

Table 7 demonstrates the significance or non-significance of the hypothesis. The hypotheses are accepted or rejected using

p-values generated by the bootstrapping technique. Analysis of the data confirmed that the hypothesized association between SETA and social bound theory is supported; H1a, H1b, H1c, and H1d are accepted. SPP has an association with social bound theory constructs (COM, PN). Nevertheless, the associations between SPP → INV and SPP → ATC are not significant. Therefore, H2b and H2d are accepted, while H2a and H2c are rejected. The association between WPC and involvement (INV) is supported. Therefore, H3c is accepted. However, WPC shows no significant association with ATC, COM, and PN. Consequently, H3a, H3b, and H3d are rejected.

The SBT has a strong association with intention to uphold security policy and procedures. Therefore, H4, H5, H6 and H7 are accepted.

To test the association between variables, PLS via SmartPLS was employed. This method was selected because of its capacity to test relationships among variables and robustness. It is also suitable for a small sample size [

77].

Figure 3 reveals that the SBT is significantly associated with ISPC with R

2 = 0.687.

Figure 3 highlights the outcomes of hypotheses testing. The results show that organizational governance affects the social bound theory constructs: ATC (R

2 = 0.271), COM (R

2 = 0.194), INV (R

2 = 0.208), and PN (R

2 = 0.357). From

Figure 3, personal norms are shown to have a strong association with ISPC (β = 0.389,

p < 0.00). In contrast, attachment (β = 0.285,

p < 0.00), commitment (β = 0.229,

p < 0.00), and involvement (β = 0.240,

p < 0.00) have a moderate association with ISPC.

5.5. Common Method Bias

In this study, the threat of common method bias (CMB) was assessed [

73,

74]. The general techniques for controlling CMB proposed by Podsakoff et al. (2012) were initially followed, namely, procedural and statistical control [

74]. For procedural control, the researcher measured the predictor and criterion variables from different sources, protecting the respondent’s anonymity, and improving the scale items. For statistical control, the researcher conducted two independent analyses to examine the effect of common method bias: the variance inflation factor (VIF) and the correlation matrix [

75]. Kock (2015) argued that a value of VIF greater than 3.3 indicates that the model has pathological collinearity and the presence of common method bias [

76]. Here, the test using SmartPLS was performed, and all of the values of VIF were found to be less than 3.3.

Table 4 demonstrates that the VIF of SETA, SPP, WPC, ATC, COM, INV, PN, and ISPC are within the threshold limit. The maximum VIF value is 3.037 of SPP3, as shown in

Table 4. We also evaluated the correlation matrix, as shown in

Table 8. An extremely high correlation between any two constructs causes methodological bias [

77]. The correlation table does not depict any high factor correlation. The highest correlation is equal to 0.8. Thus, procedural and statistical control techniques suggest that the data are free from common method bias and collinearity.

5.6. Correlation of Constructs

Table 8 demonstrates the correlation between the study variables. Cohen (1988) described the acceptable range of correlation by emphasizing the following: there is a weak correlation between constructs when values fall between ± 0.10 and ± 0.29, a moderate correlation between variables when values range from ± 0.30 to ± 0.49, and a strong correlation when values range from ± 0.50 to ± 1 [

68]. In

Table 8, ISPC has a strong association with attachment (0.76), commitment (0.68), involvement (0.69) and personal norms (0.73). There is a moderate association between ISPC and SETA. From

Table 8, SPP (0.29) and WPC (0.21) are shown to have a weak association with ISPC.

6. Discussion

Our results provide evidence that organizational governance factors proved to enhance social bonding among employees, and improved social behavior among employees enhances information security policy compliance in the O&G sector. This section contains three parts—i.e., theoretical contribution and implications, practical implications, limitations, and future research.

RQ1: What is the contribution of organizational governance factors in promoting the social behavior of employees in O&G organizations in developing countries?

The results provide sufficient evidence to support the notion that organizational governance has a positive influence on employees’ social bonding—i.e., attachment, involvement, personal norms, and commitment—with respect to ISPC at work. The analysis indicates that the more effective the organizational governance is in terms of control of IS security issues, the more likely the employees will bond in the context of mitigation of IS security problems. This finding is in line with the management literature suggesting that collegial bonding improves overall organizational performance [

80,

81,

82]. This work has a direct and positive impact on the information security practices in O&G sector organizations. The data analysis revealed that organizational governance factors significantly influence employees’ social bonding in an organization. SETA programs were proven to be very useful for increasing the knowledge and social bonding among employees. It has been shown in the data analysis that SETA programs positively influence an employee’s overall social bonding—i.e., attachment, commitment, involvement,—and his personal norms towards organizational security policies. According to Hsu et al., better social bonding of employees enhances the security culture of an organization [

22]. As explained in the literature, security problems typically arise because of the lack of an information security culture in organizations. SETA programs, however, are used to enhance the security culture of organizations. This finding is consistent with these studies [

69,

70].

The results also revealed that SPP influences commitment and personal norms of an employee towards organizational security policies. As Ifindo 2018 explained in detail, aligned security policies and procedures can improve an employee’s commitment and his views about the importance of information security [

36]. Moreover, this result is similar to multiple studies, such as those of Safa et al. and Kim et al. [

21,

46]. However, SPP has not shown a significant association with attachment and involvement. The reason of these failed hypotheses can be related to security-related stress. As D’Arcy et al. explained in detail, employees may perceive security policies and procedures as a barrier to their daily work routine and indulge themselves in moral disengagement that can cause detachment from security policies [

83]. Moreover, Xu et al. further explained that employees perceive information security policies as a hurdle in their daily work and they can adopt avoidance coping strategies, such as psychological detachment (less attachment to security tasks) and procrastination (less involvement in security tasks) [

84]. WPC is proven to be a less effective motivator of social bonds. The analysis results show that WPC only enhances employees’ involvement towards ISPC. An organization’s internal capabilities often positively influence an employee’s involvement with organizational activities [

71]. An apparent reason for the failure of WPC towards ATC, COM, and PN could be the different work environment of employees. As in this study, data were collected from managers and executives from the O&G sector, offshore and onshore. There are different workplace capabilities of upstream, mid-stream and downstream managers [

38]. Moreover, Da vaga et al. explained, in detail, that WPC is a critical factor that can influence the security culture in an organization [

6]. It is possible that the lack of significance for WPC towards social bond factors might be due to the diverse culture of O&G organizations.

RQ2: How well can social bond factors predict the behavioral intentions of O&G employees towards ISPC in developing countries?

The results of the study provided enough evidence that improved social bonding among employees can enhance the ISPC R

2 value up to 0.687. The data analysis revealed that employees’ commitment, attachment, involvement and personal norms are essential predictors of ISP compliance behavioral intention. We proposed that employees’ commitment to ISec-related tasks positively influence intention towards ISPC. A committed individual would never take the risk of violating organizational ISPs. Fortunately, the result of the analysis showed a substantial relation between commitment and employees’ intention to compliance, with a beta value of 0.229. This finding is in line with Hearth et al. and Posey et al. According to Hearth et al. [

85] and Posey et al. [

86], commitment is a crucial factor that enhances employees’ intention towards ISP.

Similarly, data analysis revealed that Attachment and ISPC also has a significant relationship. Furthermore, the attachment of employees to ISec policy compliance, our results are the same as those reported by Cheng et al. [

60], who showed that if an employee’s views are the same as his/her colleagues, he/she will be more likely to adhere with organizational policies [

14,

87,

88,

89]. Furthermore, the data analysis provides evidence that employee involvement in organizational activities determines his intentions towards ISPC. This finding is in line with [

14,

23]. The last and effective construct in the framework that influences employees’ intention towards organizational ISP is personal norms. Personal norms are the beliefs of an individual, which bound him to comply with ISPs of the organization. The data analysis provided enough evidence that employees’ intentions to comply with organizational ISPs is positively influenced by their personal norms. This finding is correlated with that of Yazdanmehr et al. [

90] in terms of employees’ ISPC. These findings also mirror the observations reported in similar studies [

23,

46,

60] showing that enhanced social bonding of employees at work promotes adherence to IS security rules and regulations.

The results of this study proved that lack of social bonding among employees of O&G organizations of developing countries causes non-compliance towards ISP of the organization. The analysis further revealed that good social bonding among O&G employees provides support to the management to implement ISPs successfully in their organizations. In the same way, regression analysis provided enough support that all social bond factors (ATC, CT, INV, PN) adequately predicted employees security behaviors.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Theoretical Contributions

This paper offers multiple contributions to the ISs security management literature. To the best of our knowledge, this is among the first studies to incorporate organizational governance and social bond factors for the use of O&G sector information security discourse. This integrative conceptualization provides a new perspective to understand behavioral ISec intentions of O&G employees. We believe that this conceptualization is complementary to other, widely publicized research based on the protection motivation theory and general deterrence theory. Furthermore, this research supports the assumptions in SBT regarding the perception of group influences and social/personal norms that can help to discourage deviant behaviors with respect to ISec policy compliance. Moreover, it does not seem that employees want to comply with the ISP of his or her organization because of perceived sanctions or punishments [

25,

85]. The data analysis of this current research seems to indicate, to a lesser degree, the emerging point of view in the literature [

91,

92], illustrating that deterrence theory or protection motivation theory is not sufficient to assess employee compliance/non-compliance with ISPs and that more investigation is required with respect to social influences and social cognition. This study enhances the findings of previous social component research regarding ISPC [

23,

36]. Moreover, the control variables studied and their effect on ISPC revealed that the participants’ age and experience influenced how they developed their intentions for security policy compliance. As the participants’ age and experience increased, their intention to violate security policies decreased, which is consistent with findings from previous ISs usability studies [

1,

26,

93].

7.2. Practical Implications and Conclusion

The results of this paper have provided several important practical implications. These findings have revealed that O&G organizations’ management can increase ISec policy compliance by providing adequate information regarding security governance. Organizational management should focus on enhancing an information security culture by providing an environment where employees can learn about organizational values and the importance of ISec policies. Furthermore, the results revealed that social bond factors are the main determinants of ISPC. Practitioners must focus on enhancing socialization among co-workers. Employees who are attached to their organizations and involved in building personal bonds with their colleagues are more likely to convince their colleagues to adhere to organizational security policies. Likewise, this study further revealed that an experienced and attached employee could advise his/her co-workers about dealing with information security issues or possible threats associated with it. Managers should focus on the enhancement of collaborative attribute development among employees, specifically, those dealing with IS security matters. The provision of advanced training and strategies to enhance communication between groups is also instructive [

94].

Second, organizational governance factors are essential for enhancements of social bonding. For good organizational governance, management should design their ISPs according to every level of the organization—i.e., they must take inputs from all top-level to bottom-level employees. In addition, company-wide relationships, including inter- and intra-unit/levels or levels, can encourage group conformity with organizational rules and requirements. The results suggested that employees’ enhanced involvement could further improve security policy compliance for the organization. When an employee knows that he/she is complying with security policies and that it is a social issue, he/she can easily guide or further advise their colleagues. For the further enhancement of compliance with ISP, management should try to foster such climates through governance such that the commitment of employees with these policies is connected to several motivations. Leadership must arrange quarterly or monthly rewards for the most compliant employees. At a certain point, management should demonstrate the negative consequences for non-compliance with ISec policies to the organization itself and employees.

Third, as social bonding appears to be an important aspect of employees’ ISPC intention, organizations must take advantage of this valuable information to enhance compliance intention. For instance, organizations can seek help from influential personalities who can shape the opinions and the mindset of employees towards ISPC. Moreover, management can assign tasks to the team leads inside organizations to motivate employees towards organizational policies. Employees with a better understanding of IS policies and behaviors must be positioned as role models so that people can emulate the behavior of individuals whose values reflect their organizations ideals [

88,

89].

Fourth, to foster good personal norms, management must focus on personal awareness regarding IS security threats and vulnerabilities. This can be accomplished through effective security education and training campaigns on such issues. A comprehensive security education and training program should enable employees to see the link between how compliance with these policies affects their jobs [

17]. Regular seminars or meetings can enable workplace socialization with respect to ISec matters and issues. Since employees are unable to link IS security policy compliance with their work responsibilities, managers should consider ISPC as a serious problem. It may be useful to reassess the interpretation of IS security risks by employees in full and reorient them. An effective information security awareness campaign on such topics could be a viable option.

O&G organizations are vulnerable to cyber threats due to their extensive use of ISs. Such systems need to be protected using information security. O&G organizations mostly focus on technical solutions for security problems rather than administrative controls to diminish internal threats. Insider threats are more crucial than outsider security attacks, so O&G organizations must think about how to control the behavioral problems of insiders. Negligence towards the organization’s ISP can cause extensive damage. The heavy work routine of O&G employees is often a cause of security-related stress and value conflicts, which are significant reasons for non-compliance towards ISP. Security-related stress and value conflicts can be mitigated with organizational governance and good social bonding. This paper demonstrates that employees’ organizational governance can increase social bonding among employees, and good social bonding cultivates ISPC. For O&G organizations that are not considered highly protected organizations, a persuasive yet effective framework has been validated to adapt essential constructs to foster ISPC.

Cybersecurity not only refers to the defense of the information superhighway but also the workforce and assets of the susceptible organization. Potential cyber-attacks can be lethal to operational controls, financial information and the work force associated with the organization under attack. The risks of these attacks can be mitigated/minimized by organizational arrangements and support for information security policy compliance. Additionally, with this sensitive issue under investigation, O&G organizations need to focus on strategic and acceptable information security policies within the organization. Fear of losing critical organizational information, due to difficult or unrealistic security policies patterns, can be dealt with by involving end-users of computing and network facilities (employees) in decisive stages of implementation of information security policies. It is time to focus upon shared visions/goals of dealing with cyber-attacks in critical energy infrastructures, especially in the O&G sector.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

Similar to all empirical research papers, this research has some limitations that should be mentioned. First, while common method bias was not an issue for the research study in this paper, the possibility that most of the respondents provided socially desirable answers for some of the constructs nevertheless exists. Second, the model only focuses on the intention towards security policy compliance and does not address the intention–behavior gap. Third, the data were collected from respondents who both had formal ISPs implemented in their organizations and from those without formal ISPs; the inclusion of both types of respondents might have adverse effects on the results. Complementary to this, the questionnaire used provided complete information about this study to the respondents, and a comparison of responses from both groups did not establish any statistically significant difference. Fourth, the researcher took three vital constructs from organizational governance; however, multiple other governance constructs can affect the social bonding of employees. Thus, in the future, research should include more constructs, such as risk assessment analysis, physical security monitoring, whistleblowing, and employee neutralization. All these governance factors can have significant effects on employee behavior.

Future research in this area could overcome some of the limitations discussed in this study. First, in the future, a longitudinal study is required that may improve the statistical results. Second, future studies may include all the PMT elements for exploring motivation effects on the social bonding of employees. Third, future work could incorporate mediation effects of all the organizational governance factors with social bond factors on ISPC. Fourth, the researcher used ISP compliance intention rather than ISP actual compliance behavior, which means this framework is measuring intentions and not actual behavior. Although the intention is the best predictor of actual behavior [

14], actual behavior can be different from intentions. Nevertheless, there must be a way to measure employees’ actual ISP compliance; this would improve the empirical and practical results of ISPC research. Fifth, since only Malaysia’s O&G organizations were selected for the data analysis, a possible avenue for future study will be to extend this model to include a cross-cultural analysis to determine whether cultural differences affect ISPC in O&G organizations.