Taboos/Norms and Modern Science, and Possible Integration for Sustainable Management of the Flyingfish Resource of Orchid Island, Taiwan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Flyingfish Culture Related T&N and Their Ecological Conservation Implications

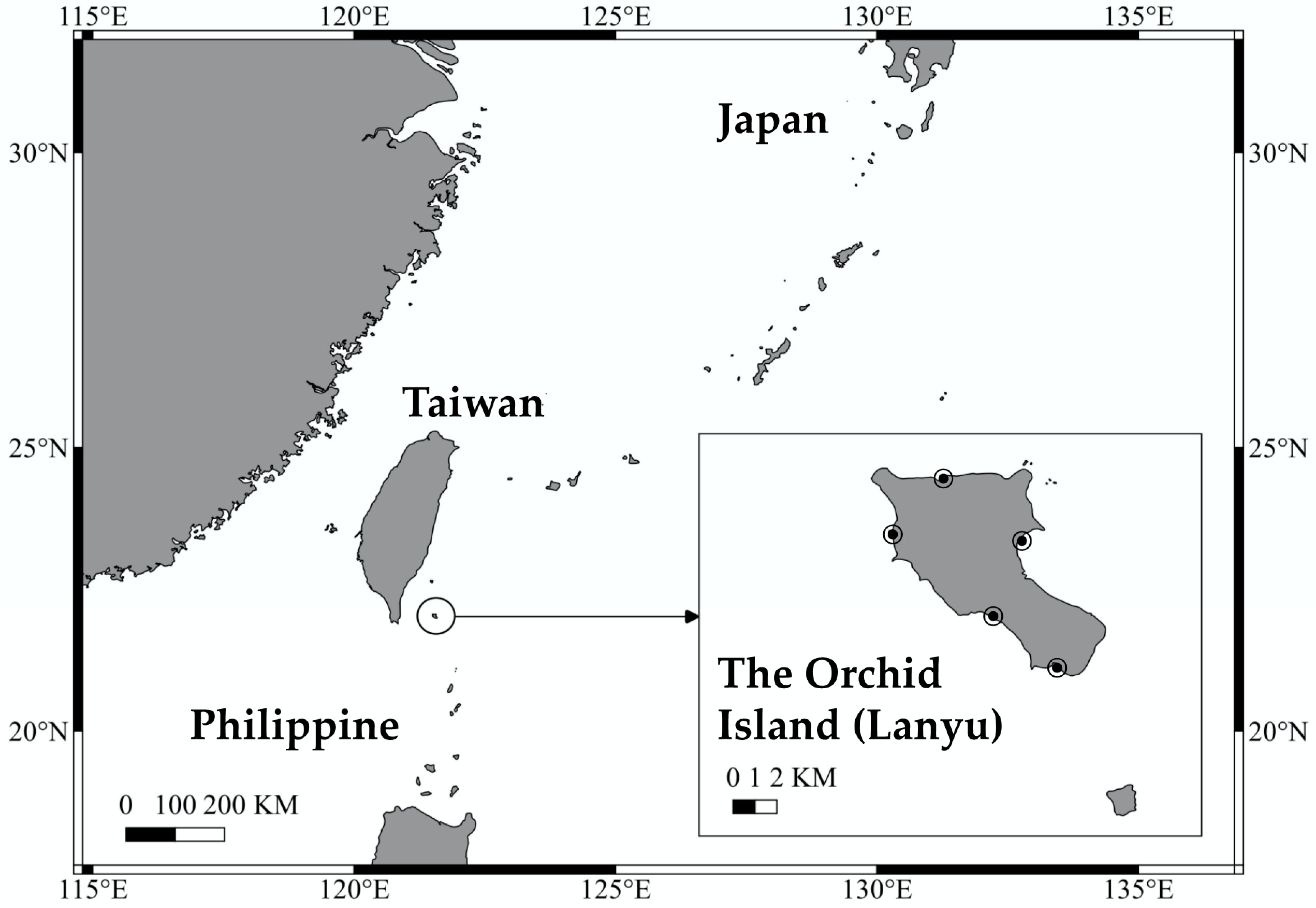

2.2. Flyingfish Catches with Respect to Fishery and Biological Aspects

3. Flyingfish Culture Related T&N and Their Ecological Conservation Implications

3.1. The T&N Related to the Flyingfish Culture

3.1.1. Respect

3.1.2. Luck

3.1.3. Exorcism

3.1.4. Others

3.2. The T&N with Ecological Conservation Implications

4. Flyingfish Catches With Respect to Fishery and Biological Aspects

4.1. Fishery Information

4.2. Biological Information

5. Suggestions for Integrated Resource Management Scheme

5.1. Enhancing Cultural Self-Recognition and Highlighting the T&N with Ecological Conservation Benefits

5.2. Integrating TEK with Science-based Monitoring, Control, and Surveillance (MCS) and Research

5.2.1. Monitoring

5.2.2. Control

5.2.3. Surveillance

5.2.4. Research

5.3. Highlighting and Strengthening Autonomous Decision-Making Function Necessary to Become an ICCA

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Code | Taboos and Norms | Plausible Motives or Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| R01 | Playing in or throwing stones toward the sea are prohibited during flyingfish season, and women must not get close to the shore. | To show respect to the coming of flyingfish. |

| R02 | Fishing with nets, spear guns, or fishing poles for other fish species is strictly prohibited during the flyingfish season. | To show respect to flyingfish and focus on celebrations of the flyingfish festivals. Catching other fish is prohibited before the “ceremony to mark the end of catching flyingfish” (around July); it is believed to be necessary to maintain the resources of other fish species. |

| R03 | Do not say any ominous words, do not point at the flyingfish in the sea, and do not wash food in the river. | According to tradition, if any ominous word is spoken when the fishing groups are living together, all of the fish must be discarded. If any child speaks ominous words during the flyingfish season, they are punished (Tao people normally do not punish their children because it is considered as a bad omen). During the flyingfish season, tribespeople will cook food with seawater’ thus, if a tribesperson were to wash their food in the upper river, the sea will be contaminated. |

| R04 | The harvested flyingfish need to be blessed with sea water first before the scale-removing process, and the removed scales need to be returned to the sea. | Returning fish scales to the sea shows gratitude to nature for providing food. The scales also draw big fish closer to the shore. Returning scales to the sea can also prevent the breeding of maggots on the shore. |

| R05 | Everyone must be wearing traditional clothing with gold and agate as accessories on their first flyingfish feast for celebrations. | The first flyingfish caught is a symbol of good luck, and is shared and celebrated with the fisherman’s family. The first fish shall not be used as bait. |

| R06 | Flyingfish must be cooked by boiling method only; roasting or deep frying are prohibited before "flyingfish daytime feasting festival" (around May). | In Tao myth, a person who eats roasted fish will grow sores on their body. Following the “flyingfish daytime feasting festival” is the month of Peypilapila (a month based on Tao’s calendar system when the “flyingfish storage festival” will be held; this occurs around June and most flyingfish taboos end at that time). According to tradition, the most skillful person at fishing or someone who caught a mahi-mahi fish (Coryphaena hippurus) will slaughter a pig as a sacrifice to the sea god, telling the god that they will roast the fish; only then they can start roasting the fish. |

| R07 | Sea water must be used to cook flyingfish and the pot must not be covered until all flyingfish are in the pot. When the water boils, a dry reed must be lit as illumination. | Seawater symbolizes a blessing. The fish are not edible if they are not cooked with the ataw (seawater from the nearby beach, which is also a means to season the food). The ash from the wood fire is considered unlucky, so must be exorcized with a dry reed. |

| R08 | Flyingfish are not allowed to be cooked with other foods (non-staple food like shellfish or pork) and must be cooked and served in their specific cooking ware and dinner ware. | The flyingfish is recognized as a sacred fish; cooking and mixing it with other foods will cause disease. |

| R09 | Leftover flyingfish will be cooked with taro (staple food). | Taro can only be harvested once per year, so is a precious food source for the tribe, and is often served as a staple food with flyingfish and other big fish. |

| R10 | Flyingfish must be hung properly and never dropped on the floor; rocks must not be thrown toward the fish rack. | No disrespectful behavior toward flyingfish. |

| R11 | During the “ceremony to mark the end of catching flyingfish” (around July), the fins of flyingfish and other big fish are removed and left on the rocks of the right-hand side of the harbor, allowing them to be flushed back to the sea. | Symbolizing a revival ritual of flyingfish and other big fish. |

| L01 | People are not allowed to speak, rock the boat, or yell when they sight flyingfish during nighttime fishing. | Yelling flyingfish are sighted will draw evil spirits to the boat. The tribe does not mention anything if they are going for fishing, because the evil spirt will affect their fishing conditions. |

| L02 | It is best to catch an odd number of fish on the flyingfish season. A chicken can be brought on the boat if fish are not caught. | Traditionally, odd numbers are considered good luck. The ideal number of fish caught is three, followed by one, five, seven, and nine. They believe the clucking of a chicken will attract the fish. |

| L03 | When carrying fish back to their house, fishers must walk a specific route and avoid walking past neighbors’ houses. | When someone walks past a neighbor’s house carrying flyingfish, it will affect the neighbor’s fishing luck. |

| L04 | All fishing boats have to depart before sunrise on "small boats daytime fishing festival" (around May). | This may relate to the foraging time of big fish, which usually starts around 3–4 am. |

| L05 | Trespassing by other families to the flyingfish festival is forbidden. | The fishing luck will be "stolen" by others. |

| L06 | It is prohibited for people from other tribes to fish in a tribe’s territorial waters, eat fish caught by the tribe, or trespass into the tribe’s area. | The fishing luck will be stolen by the people of other tribes if they enter the territory of the tribe. |

| L07 | In Kasiyaman and Paneneb (a calendar system used by Tao people, in which the beginning of the flyingfish season is around February to March), the fish harvested during nighttime must be left overnight in the boat until the following morning. The fish can only be taken directly back home at Pokokaod (when the fishing group of big-boats is disbanded, around April). | The fish will leave overnight in the boat to avoid being noticed by the evil spirit. The roaming dogs and pigs on the island will steal the fish in the boat, so the tribe will stay and guard their fish. |

| L08 | Orange and Indian Barringtonia (Barringtonia asiatica) are two taboo things in Tao culture. Do not mention the two things and do not bring orange to the ship or give as a treat. Eating snails and ginger is also prohibited during fishing. | One tribesperson said that Indian Barringtonia is known as an unholy plant because it often grows near graveyards; others said that the pronunciation of Indian Barringtonia is similar to "medicine" in the language of the Ivatan (a nearby tribe in Philippines), and the pronunciation of oranges is similar to "no fish" in the Tao language. |

| L09 | The drying fish rack must be surrounded by a bamboo wall and no one is allowed to enter, especially pregnant women or midwives. | The bamboo wall will guard the fishing luck; the luck will be "stolen" if others get too close. |

| L10 | Flyingfish must be served whole; cutting in into pieces is not allowed. | Eating flyingfish in pieces will bring bad luck to fishing. |

| L11 | During the "boat festival," all boats must be parked at the right-hand side. The first flyingfish caught from the left-hand side must be pulled out from the right-hand side. Flyingfish must be cook on the right-hand side of the house. | “Right” symbolizes big and precious, and “left” symbolizes small and common. “Right” actually means the direction of the sunrise and left/right is relative to the direction facing the sea; for example, in Yuren village, when facing the sea, the sun will rise on the left-hand side, so villagers build their stoves at their left-hand side; however, for the Yeyin village, on the other side of the mountain, villagers build their stoves in the opposite direction. |

| L12 | Housework, such as weeding, house building, or boat building, is prohibited when the members of a fishing group are living together. | There are many things to do during flyingfish season. It is considered taboo if housework is performed instead of focusing on fishing, and tribespeople will not catch any fish. |

| L13 | Weaving by women is prohibited during the flyingfish season, because it will cause bad luck for their husband’s fishing trip. | Women have to help with the cropping work and preparing of the fish. Weaving is considered a task during their spare time, so if they are; thus, weaving indicates they have nothing to do, thereby bringing bad luck to their husband’s fishing trip. |

| L14 | Women are not allowed to touch men’s fishing gear, approach the shore, or participate in the flyingfish festival. Intimate acts between husband and wife are forbidden when members of the fishing group are living together. | Men believe that they will fail to catch fish or even lose their offspring if their boat is touched by women. Intimate acts are forbidden probably because they wish to focus on fishing. |

| L15 | Women, especially pregnant women, are considered taboo to fishing activities. For example, a fisherman will fail to catch any big fish if his wife is pregnant. Cooking and collecting of dry flyingfish must be done by men, and women can only help with fish cleaning and gutting. | Tribal tradition states that if a pregnant woman turns over a reef rock, it will cause a tsunami. Others say the belly of pregnant women are round; round things roll, so the fish will roll away and escape. Thus, pregnant women are only allowed to eat fish caught by her own family and no one else, otherwise the fishing luck will be affected. Furthermore, all flyingfish related work is mostly done by men. |

| E01 | Tao people will spread charcoal ash inside their boat during nighttime fishing. | Charcoal ash symbolizes "destroy," similar to salt or shellfish ash, and is often used in the exorcism of evil spirits. |

| E02 | The people will place a cross made of dry reeds on the boat if any fish are caught during the flyingfish season. | A cross made of dry reeds will stop and prevent haunting by evil spirits. |

| E03 | Wives and children must stay home if their husband/father are still on the shore and not yet fishing. | To avoid notice of evil spirits and preventing the husband/father from going fishing, or let the husband/father ensure the safety of their family and keep their focus on the fishing trip. |

| E04 | Harvesting of common phytia (Pythia scarabaeus or namisil in Tao language) are prohibited. | The reef rock needs to be pried open to harvest the common phytia. According to tribal tradition, the gesture of “pry open” will cause the boat to turn over. |

| E05 | Flyingfish caught by a fishing group must be eaten within a day or a week. Every family member of a fisherman must eat the fish before noon. Jianachan (unfinished fish in the morning) will be discarded after 1–2 pm and a new batch of dried flyingfish will be cooked afterward; however, this fish will also be discarded if not finished before sunset. | Stocking of flyingfish is prohibited during the start of flyingfish season. The fish must be eaten or given away as gift. Any leftover flyingfish is considered unlucky; an evil spirit will come and share the flyingfish. |

| E06 | All harvested flyingfish must be processed before sunset (before 3 pm). | The daytime and direction of sunrise is considered good luck. Tradition says that evil spirits will come out and share the flyingfish after sunset. |

| E07 | If one tribesperson passes away, the whole tribe will stop fishing, hunting, or farming activities for 3–7 days to mourn their death (in the present day, the mourning period is reduced to 1 day due to the increase in tourism demand); the family of the deceased must rest for one month before resuming fishing and are not allowed to participated in the "flyingfish summoning ritual". | Tao people believe that one will turn into an evil spirit after death. If someone dies, the deceased will be buried in a cemetery and no praying or funeral will be held, and the local tribe will place bamboo or a wooden board in front of the door to prevent being haunted by the evil spirit. The family of the deceased will not participate in festivals and the name of the deceased will not be mentioned to ease their grief. |

| O01 | Adult men should get their hair cut at the beginning of flyingfish season. | A haircut symbolizes a fresh start. According to tradition, if one does not get a haircut, he will be considered an orphan and will be mocked and made fun of by others. |

| O02 | Flyingfish caught by a fishing group must be shared equally among members; selling or taking more than they need is prohibited. | Tao people share not only their harvested fish, but everything that can be shared. They claim that sharing united the Tao people and it is the feature of their culture about which they are the proudest. |

| O03 | Only one fishing trip per day is allowed during the flyingfish season. | To prevent competition and overfishing. |

| O04 | The drying process of flyingfish can only be undertaken by adult men. Flyingfish will be placed horizontally in the daytime and hang vertically during nighttime. | The flyingfish is mostly placed horizontally during early times; the fish is hung vertically when there are more fish harvested to save hanging space. The fish head must point inside the house when placed horizontally, meaning more fish are welcomed into the house; the fish head is only allowed to point toward the sea after the "small boats daytime fishing festival." In the present day, only Hongtou and Yuren villages place their flyingfish horizontally; other villages hang their fish vertically. |

| O05 | The eyeball of the flyingfish must be eaten raw, before any other part; however, women are not allowed to eat the eyeball. | The fish eyeball is considered to be good for health, so has to be eaten in its freshest state (raw). Women are not allowed to approach the shore. The eyeball will no longer be fresh when taken home, so women are not allowed to eat the eyeball. To prevent the eyeball from rotting, it must be removed first during the drying process. In early times, the fish eyeball was taken as breakfast due to a shortage of food. |

| O06 | Any preserved or stored fish at home should finished first before flyingfish is eaten. | To prevent food being wasted. |

| O07 | All flyingfish must be finished or discarded before manoyotoyon (ceremony marking the end of flyingfish consumption, around October); following this ceremony, Tao people are not allowed to eat flyingfish until the next season starts. | Tao people believed that any leftover flyingfish in the home will bring bad luck to their family. Due to a lack of food preservation methods in early times, this is believed to be associated with health and sanitation considerations. |

| O08 | Edible fish species are divided into three groups: "elder’s fish,” “man’s fish,” and "women’s fish." Women are not allowed to eat "man’s fish." | Generally, "women’s fish" are difficult to catch but have the best quality, and are edible for both women and men. "Men’s fish" are easier to catch but have lower quality, and may only be eaten by adult men. Unusual or ferocious looking fish, or those with the lowest quality fish, are classified as "elder’s fish,” and mainly eaten by experienced elders. Flyingfish is edible for all people. |

References

- Johannes, R.E.; Freeman, M.M.R.; Hamilton, R.J. Ignore fishers’ knowledge and miss the boat. Fish Fish. 2000, 1, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannes, R.E. The case for data-less marine resource management: Examples from tropical nearshore fin fisheries. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1998, 13, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Jorgensen, J.; Josupeit, H.; Kalikoski, D.; Lucas, C.M. Fishers’ Knowledge and the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries: Applications, Experiences and Lessons in Latin America; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 591; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, J.M. Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Practical Roles in Climate Change Adaptation and Conservation; NOVA Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, A.; Ruddle, K. Constructing confidence: Rational skepticism and systematic enquiry in local ecological knowledge research. Ecol. Appl. Publ. Ecol. Soc. Am. 2010, 20, 880–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-P.; Tang, S.-Y. Institutional adaptation and community-based conservation of natural resources: The cases of the Tao and Atayal in Taiwan. Hum. Ecol. 2010, 38, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-M.; Lu, D.-J. The cultural and ecological impacts of aboriginal tourism: A case study on Taiwan’s Tao tribe. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chang, S.-K.; Chang, C.-W.; Ame, E. Species composition and distribution of the dominant flyingfishes (Exocoetidae) associated with the Kuroshio Current, South China Sea. Raffles Bull. Zool. 2012, 60, 539–550. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.-M.; Chang, S.-K. Changes in local knowledge and its impacts on ecological resources management: The case of flyingfish culture of the Tao in Taiwan. Mar. Policy 2019, 103, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klooster, D. Institutional choice, community, and struggle: A case study of forest co-management in Mexico. World Dev. 2000, 28, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Ostrom, E.; Stern, P.C. The struggle to govern the commons. Science 2003, 302, 1907–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brosi, B.J.; Balick, M.J.; Wolkow, R.; Lee, R.; Kostka, M.; Raynor, W.; Gallen, R.; Raynor, A.; Raynor, P.; Lee Ling, D. Cultural erosion and biodiversity: Canoe-making knowledge in Pohnpei, Micronesia. Conserv. Biol. 2007, 21, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujarwo, W.; Arinasa, I.B.K.; Salomone, F.; Caneva, G.; Fattorini, S. Cultural erosion of Balinese indigenous knowledge of food and nutraceutical plants. Econ. Bot. 2014, 68, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, B.F.; Cevallos E., J.; Santana M., F.; Rosales A., J.; Graf M., S. Losing knowledge about plant use in the sierra de manantlan biosphere reserve, Mexico. Econ. Bot. 2000, 54, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswani, S.; Lemahieu, A.; Sauer, W.H.H. Global trends of local ecological knowledge and future implications. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellado, T.; Brochier, T.; Timor, J.; Vitancurt, J. Use of local knowledge in marine protected area management. Mar. Policy 2014, 44, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, A.A. Changing U.S. ocean policy can set a new direction for marine resource management. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gerhardinger, L.C.; Godoy, E.A.S.; Jones, P.J.S. Local ecological knowledge and the management of marine protected areas in Brazil. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2009, 52, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frans, V.F.; Augé, A.A. Use of local ecological knowledge to investigate endangered baleen whale recovery in the Falkland Islands. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 202, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decrop, A. Triangulation in qualitative tourism research. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.P.G.; Andriamarovololona, M.M.; Hockley, N. The importance of taboos and social norms to conservation in Madagascar. Conserv. Biol. 2008, 22, 976–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuno, A.; St. John, F.A.V. How to ask sensitive questions in conservation: A review of specialized questioning techniques. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 189, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, G.-H.; Dong, S.-Y. The History of Indigenes in Taiwan: Volume of Yamis (In Chinese); The Historical Research Commission of Taiwan Province: Taipei, Taiwan, 1998; ISBN 957-02-3140-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rapongan, S. The Mythology of Badai Bay (In Chinese); Linking Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 2011; ISBN 957-08-3877-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C.-W. Ritual fishing practice and usage of fishing grounds by the Yami of Yayu Village, Irala (Orchid Island). Geogr. Res. 1991, 17, 147–192. [Google Scholar]

- Rapongan, S. Originally an Island of Plenty-Marine Knowledge and Culture of the Tao People. Master Thesis, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu, Taiwan, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.-Y. Exploring the Taiwan Aboriginal Cultural Activity: Flyingfishes Festivity of the Native Tribe Tau of the Lanyu Island. Master Thesis, Ming Chuan University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.-W.; Wang, K.-C. The inquiry of Yami shell culture on Botel Tobago. J. East. Taiwan Stud. 2008, 11, 65–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Y. The Influence on Traditional Culture of Tao People When Developing Ecotourism. Master Thesis, National University of Kaohsiung, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J. “Spirits fly slow” (pahapahad no anito): Traditional ecological knowledge and cultural revivalism in Lan-Yu. J. Archaeol. Anthropol. 2008, 69, 45–107. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.-L.; Liu, P.-H. Social Structure of the Yami, Botel Tobago; Academia Sinica: Taipei, Taiwan, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Esiri, J.M.; Ajasa, A.O.; Okidu, O.; Edomi, O. Observation research: A methodological discourse in communication research. Res. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2017, 7, 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Aizawa, M. Exocoetidae flyingfishes. In Fishes of Japan With Pictorial Keys to the Species, English Edition; Nakabo, T., Ed.; Tokai University Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2002; pp. 552–561. [Google Scholar]

- Parin, N.V. Exocoetidae. Flyingfishes. In The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Pacific. 4. Bony Fishes, Part 2 (Mugilidae to Carangidae). FAO Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes. (pp. 2069–2790); Carpenter, K.E., Niem, V.H., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1999; Volume 4, pp. 2162–2179. [Google Scholar]

- Martinson, B. Song of Orchid Island; Crown Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 1992; ISBN 957-33-0795-2. [Google Scholar]

- Acheson, J.M. Anthropology of Fishing. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1981, 10, 275–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-K. Development of an Indigenous and Community Conservation Area (ICCA) in Taiwan (III)—The Monitoring System in Marine ICCA Taking Flyingfish Fishery as an Example; Project Report of the Ministry of Science and Technology (Project number: MOST103-2621-M-020-001); MOST: Taipei, Taiwan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Golden Gate Weather Services. El Niño and La Niña Years and Intensities. Available online: https://ggweather.com/enso/oni.htm (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Liu, C.-C. Growth, Reproduction and Management Implication of Cheilopogon unicolor off the Eastern Taiwan. Master Thesis, National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, I.-H. Growth, Reproduction and Management Implication of Cheilopogon atrisignis in the Orchid Island off Eastern Taiwan. Master Thesis, National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UKEssays. The Cultural Myths of America. Available online: https://www.ukessays.com/essays/sociology/the-cultural-myths-of-america-sociology-essay.php (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Martinez, D. Deconstructing myths influencing protected area policies and partnering with indigenous peoples in protected area co-management. In Rethinking Protected Areas in a Changing World: Proceedings of the 2007 George Wright Society Biennial Conference on Parks, Protected Areas, and Cultural Sites; Weber, S., Harmon, D., Eds.; The George Wright Society: Hancock, MI, USA, 2008; pp. 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Appiah-Opoku, S. Indigenous Beliefs and Environmental Stewardship: A Rural Ghana Experience. J. Cult. Geogr. 2007, 24, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.J.; Ignace, M.B.; Ignace, R. Traditional ecological knowledge and wisdom of aboriginal peoples in British Columbia. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1275–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-P.; Tang, S.-Y. Negotiated autonomy: Transforming self-governing institutions for local common-pool resources in two tribal villages in Taiwan. Hum. Ecol. 2001, 29, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flewwelling, P. An Introduction to Monitoring, Control and Surveillance Systems for Capture Fisheries; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1999; p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.-K.; Liu, K.-Y.; Song, Y.-H. Distant water fisheries development and vessel monitoring system implementation in Taiwan-History and driving forces. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G. Bio-Cultural Diversity Conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities: Examples and Analysis. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/content/bio-cultural-diversity-conserved-indigenous-peoples-and-local-communities-examples-and-analysis (accessed on 29 August 2020).

- UNEP-WCMC. Global Databases to Support ICCAs: A Manual for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities; UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK, 2016; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

| Code | Taboo/Norm (in Brief) | Ecological Implication |

|---|---|---|

| O02 | Flyingfish caught by a fishing group must be shared among members and cannot be sold. | Catch control: control the catch enough for their own needs. |

| E05 | Flyingfish caught by a fishing group must be consumed in a day or a week in the early period of the season. | Catch control: control not to fish over their needs for consumption. |

| R06 | The harvests must be cooked by boiling method before daytime feasting festival (about May). | Catch control: reduce the consumption for restaurants that sell fire roasting fish. |

| O06 | Any preserved or stored fish in the home should be finished first before flyingfish are eaten. | Catch control: reduce consumption and avoid waste. |

| R09 | Boil and consume unfinished flyingfish with taro as staple diet. | Catch control: reduce consumption and avoid waste. |

| O07 | Discard all stored flyingfish after the festival marking the end of flyingfish consumption (approximately in October). | Catch control: encourage not to fish flyingfish over their needs. |

| L15 | Women cannot participate in fishing activities. | Effort control: reduce fishing manpower. |

| E07 | Family having a funeral cannot go fishing for some time. | Effort control: reduce fishing efforts in the sea. |

| O03 | Only one fishing trip per day is allowed during flyingfish season. | Effort control: reduce fishing efforts and avoid overexploitation. |

| O08 | Categorization of fishes into three groups: men’s fish, women’s fish, and elders’ fish. | Effort control: reduce fishing efforts for a single fish or a few fish resources. |

| R04 | Harvests of flyingfish must be blessed with sea water and undergo scale-removing process. | Effort control: time-consuming scale-removing process can reduce fishing time at sea. |

| E06 | Process of flyingfish harvests must be finished by sunset. | Effort control: reduce fishing time at sea. |

| L06 | Fishers of a tribe cannot fish in the waters of other tribes. | Effort control: reduce excessive fishing efforts in other fishing grounds. |

| R02 | Fishing with nets, spear gun, or fishing poles for other fish species (mainly the coral reef fishes) is strictly prohibited during the flyingfish season. | Closed fishing season: no fishing efforts in the spawning season of coral reef fishes (overlapping with flyingfish season). |

| 2015 | 2014 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fishing Methods | Catch Estimates | Catch Proportion | Catch Estimates |

| Motorized netting | 225,430 | 93.05% | 263,800 |

| Flyingfish net—night | 204,275 | ||

| Flyingfish net—day 1 | 4620 | ||

| Drive-in net | 16,535 | ||

| Tatala small boat | 3025 | 1.25% | 4000 |

| Tourism net 2 | 1200 | 0.50% | 2400 |

| Coastal net 3 | 3600 | 1.49% | 4800 |

| Unrecorded catch 4 | 9000 | 3.72% | 10,000 |

| Total | 242,255 | 100.0% | 285,000 |

| Species Name | Scientific Name | Local Name |

|---|---|---|

| Greater spotted flyingfish* | Cheilopogon atrisignis | papatawon |

| Limpidwing flyingfish* | Cheilopogon unicolor | sosowowon |

| Sutton’s flyingfish | Cypselurus suttoni | matezetezem so panid |

| Spotwing flyingfish | Cypselurus poecilopterus | kalalow |

| Narrowhead flyingfish | Cypselurus angusticeps | loklok |

| Blackwing flyingfish | Cheilopogon cyanopterus | mavaeng so panid |

| Bony flyingfish | Hirundichthys oxycephalus | kararakpen no arayo |

| Sailfin flyingfish | Parexocoetus brachypterus | sanisi |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, S.-K. Taboos/Norms and Modern Science, and Possible Integration for Sustainable Management of the Flyingfish Resource of Orchid Island, Taiwan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8621. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208621

Chang S-K. Taboos/Norms and Modern Science, and Possible Integration for Sustainable Management of the Flyingfish Resource of Orchid Island, Taiwan. Sustainability. 2020; 12(20):8621. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208621

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Shui-Kai. 2020. "Taboos/Norms and Modern Science, and Possible Integration for Sustainable Management of the Flyingfish Resource of Orchid Island, Taiwan" Sustainability 12, no. 20: 8621. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208621