Abstract

The paper analyses and discusses the perspectives of young people on World Cultural Heritage (WCH), focusing on their presumed reasons of its imbalanced global distribution. The qualitative study is based upon focus groups conducted with 43 secondary school students aged 14–17 years from Lower Saxony, Germany. The findings reveal Eurocentric thinking patterns. Furthermore, a site visit took place after the focus groups exploring the universal and personal values the participants attach to the WCH using hermeneutic photography. Due to these results and building upon an education for sustainable development that empowers learners to become sustainability citizens, the authors provide suggestions for a critical and reflexive World (Cultural) Heritage education.

1. Introduction

Adopted in 1972, the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and World Natural Heritage describes the protection and conservation of sites of “outstanding universal value“ (OUV) [1] (p. 19) as a task of the global community. The significance of World Heritage (WH) is defined to be “so exceptional as to transcend national boundaries and [...] of common importance for present and future generations of all humanity” [1] (p. 19). Today, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) not only calls for protecting the OUV of World Heritage Sites (WHS), but to foster culturally, economically, and ecologically sustainable uses that are based on the guiding principles of sustainable development [1]. Within the UN Agenda 2030, the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 is dedicated to cities and human settlements. In the target 11.4, it is specifically called upon to “strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage” [2] (p. 22). As a consequence of the required integration of sustainable development perspectives into the WH programme [3], World Heritage education (WHE) needs to transmit sustainability in all of its dimensions and can be directly linked to the programme Education for Sustainable Development: Towards achieving the SDGs (ESD for 2030) [4], which covers the period 2020–2030. In the accompanying framework, the UNESCO states that “the Education Sector will further strengthen its inter-sectoral partnership with other Sectors, especially Culture and Science, integrating the implementation of ESD for 2030, where possible, into their relevant programmes. These include, among others, World Heritage sites […]” [4] (p. 10). Vice versa, “there is no doubt that the implementation of the Agenda 2030 should take into account World Heritage as a strong enabler of sustainable development, thus rendering its preservation for future generations primordial” [5] (p. 29). Von Schorlemer (2020) identified three SDGs and targets as particularly important in relation to WH: target 11.4 (cities and human settlements), target 8.9 (tourism) and SDG 13 (climate action) [5]. The learning objectives for ESD formulated by UNESCO also mention cultural heritage in relation to SDG 11 [6] (p. 32).

One of the main overall goals of ESD is the empowerment of young people, as they not only have to deal with the challenges of unsustainable development in the present but will also be the decision makers in the future [7]. It is thus essential to explore their perspectives on WH, its conflicting connections to sustainability, and further related themes in order to create educational materials that acknowledge their perceptions. However, the perspectives of young people have so far not been looked at within the research field of WH. This paper, therefore, discusses selected results of a study that focused on the perspectives of 14–17-year-old secondary school students from Lower Saxony, Germany on World Cultural Heritage (WCH). Due to the nature of the explorative study and the research desideratum, no hypotheses were formulated prior to the data collection. The study aimed at exploring the perceptions, meanings, attitudes, and values of the participants towards WCH in order to develop learning materials that used the perspectives of young people as a starting point. The aim of this specific paper was to present and discuss the perspectives regarding the criteria of WCH and the imbalanced global distribution of WCHS. The paper further outlines personal and universal meanings participants ascribe to a specific WCHS in Lower Saxony.

According to Vare and Scott [8], there are two complementary approaches towards ESD: ESD 1 and ESD 2. In their view, ESD 1 is expert-driven and focuses on the transmission of a certain set of knowledge and skills that will lead to a more sustainable lifestyle. Within this approach, ESD is understood as “Learning for sustainable development” (p. 193, emphasis in original). The authors favored the approaches of ESD 2, that aim at “building capacity to think critically about [and beyond] what experts say and to test sustainable development ideas” (p. 194). Here, ESD thus means “learning as sustainable development” (p. 194, emphasis in original). Within this approach, ESD has to address and reflect on fundamental questions of power, root causes of global disparities, as well as the dominant values and perceptions that shape our views of the world. Respecting also the aims of ESD 2 for an education for sustainable development goals, UNESCO is striving for “empowering and motivating learners to become active sustainability citizens who are capable of critical thinking and able to participate in shaping a sustainable future” using pedagogical approaches which are “learner-centred, action-oriented and transformative” [6] (p. 54).

The described research in this paper proceeded from an understanding of ESD that relates to these future-related aims. Transferred to WHE, this approach requires debating uncomfortable issues such as the Eurocentrism inherent to the WH programme. Consequently, this paper focused on the aforementioned participants’ criteria for WCH and their presumed reasons for the imbalanced global distribution of WCH. The criteria for WCH, as well as the global imbalance, are closely interrelated and have caused strong debates among scholars as well as UNESCO experts. The authorized heritage discourse (AHD), of which the UNESCO is a main institution, has in the past been criticized for presenting “heritage as complete, untouchable and ‘in the past’, and embodied within tangible things such as buildings and artefacts” [9] (p. 39). Although there has been a shift from a narrow to a more complex understanding of cultural heritage and heritage conservation [10,11], the original approach left its marks [12,13]. The Eurocentric and elitist approach caused a preference of certain cultural and belief systems and is one of the main causes for the imbalanced global distribution of WCH. Of the currently 869 World Cultural Heritage Sites (WCHS), 52% are located in Europe and North America [14]. Further reasons for the imbalance are unequal financial capacities, national interests and international alignments of States nominating a site [15,16,17].

The article will first introduce the aims of WHE and point out current blind spots of the learning contents in connection to ESD 2. Secondly, it will present and discuss the perspectives of secondary school students on specific aspects of WCH. Thirdly, it will discuss the potential of hermeneutic photography for initiating “reflexive thought processes” [18] (p. 49) and for “empowering learners to question and change the way they see and think about the world” [6] (p. 55). Based on the final conclusions the authors provide suggestions for a critical and reflexive WHE.

2. World Heritage Education: Objectives and Blind Spots

Since the adoption of the World Heritage Convention, member states have been asked to offer “educational and information programmes, to strengthen appreciation and respect by their peoples of the cultural and natural heritage” [19] (p. 13). Nevertheless, the first years of the World Heritage Programme were marked by a focus on conservation and restoration, followed by an increasing touristic interest in WH [20]. Educational aspects only started to gain importance with the launch of the World Heritage Education Programme in 1994. One of the aims of the programme is to integrate WHE in the school curricula [21]. In Germany, the integration has been suggested [22], but not yet implemented by any Federal State. Nonetheless, a range of WHS and heritage institutions not only provide educational activities on site, but also classroom resources.

When looking at the proclaimed objectives of WHE, different intentions of the UNESCO, National Commissions for UNESCO and members of the scientific community become apparent. UNESCO’s World Heritage Education Programme (https://whc.unesco.org/en/wheducation/) aims at promoting awareness for the World Heritage Convention and “a better understanding of the interdependence of cultures” [21]. Moreover, young people should be made sensitive of the threats concerning WH and be encouraged to become active in its protection. Similarly, the German, Austrian, Swiss, and Luxembourg Commission for UNESCO have jointly stated that WHE fosters the awareness for identity, respect, global solidarity, and the positive exchange among members of different cultures [23]. The focus on the unifying aspects of heritage, suggests an instrumental approach that is limited to creating attachment and awareness [24,25], without questioning the definitions and procedures, the intentions, ideas, and values of the involved stakeholders and considering their geographical location.

The learning resources known to the authors only sparsely cover ESD-related topics. Examples include the resources offered by the WHS Water Management System of Augsburg [26] and the Upper Middle Rhine Valley [27] or by the preservation foundation Deutsche Stiftung Denkmalschutz [28], which deal with land-use conflicts, sustainable water management, or impacts of tourism. With regard to the aims of ESD 2, the complete lack of critical reflections on the WH system and reflexive thought processes is striking. Many available learning resources [29,30,31] merely convey the WH criteria, the nomination process, or the involved stakeholders as given facts. The imbalanced global distribution is not critically discussed in any of the learning resources known to the authors. Currently, WHE thus often confirms de Cesari’s [32] (p. 300) observation that “World Heritage not only builds upon the tradition of national heritages but in fact reproduces, amplifies and expands this tradition’s logic and its infrastructure.” Hence, a WH education that also considers the aims of ESD 2 should acknowledge the fact that WH is the result of a national and international negotiation process in order to debate on (global) political hierarchies, Eurocentrism, or repression of minorities [33]. Apart from this critical thinking approach it is necessary to widen heritage interpretation—as process and not product—to “places of the (re)creation of collective memory in which many perspectives, subjectivities, identities and values could be freely exchanged” [34] (p. 29). Hence, by means of reflexive methods a subjective or personal sense of place can be developed.

This conclusion points to a necessary shift towards a critical and reflexive WHE that explicitly addresses the shown blind spots. Further, it seems crucial to first explore the perspectives of young people on WH in order to create learning materials and methods, that explicitly integrate their views and possibly challenge existing stereotypes and meanings.

3. Empirical Study: Methods and Sampling

This qualitive study explored perspectives of high-school students aged 14–17 years on WCH using focus groups and hermeneutic photography [35]. This specific age group was chosen with regard to the school curriculum of Lower Saxony, Germany. Starting in ninth grade, spatial evaluation, awareness, and responsibility are central aspects of spatial competence, which offer various linkages with World Heritage Education [36]. It has to be noted, that school curricula and textbooks are different in each federal state of Germany. Since one of the overall aims of the study was to set a ground for the development of learning materials for textbooks, only students from Lower Saxony participated in the study. For the purpose of this article, only selected results will be discussed. It has to be stressed, that the focus was purely on cultural heritage, while perceptions on World Natural Heritage (WNH) were not part of the study.

The data were collected between May 2017 and September 2018. In total, 43 students (12 groups) from Lower Saxony, Germany, participated in the study (Table 1)—27 students identified as female, 16 as male. To acquire participants, schools and teachers were contacted by the researcher. After a short introduction of the research project in the classrooms, students could decide whether they wanted to voluntarily participate in the project. With each group of students, the researcher arranged three meetings in their leisure time.

Table 1.

Overview of the sample.

Six groups were from Hanover, a city without a WCHS, and six groups came from the three WCH cities in Lower Saxony (Alfeld, Goslar and Hildesheim, Germany). As Table 1 shows, from every WCH city, two groups participated in this study. It was decided to equally include students from a WCH city and a non-WCH city to allow comparisons between the groups.

Each of the 12 groups participated in two focus groups (Session 1 and Session 2). The second session was conducted one week after the first one. The length of the sessions varied between 18–60 min, depending on the participants’ willingness to discuss. The research project was not part of the school curriculum and the participating students were thus not graded. While the focus groups with the students from Hanover were conducted at the facility of the university, the other students were met at their school premises. This option was chosen, since traveling to Hanover would have been too time-consuming for the students. The focus groups and site visit took place after official school hours. Of all groups, only one declared that they had previously dealt with WCH in school. This group formed an exception, as the participants took part in a school project on the WCHS in Alfeld. The imbalanced global distribution of WCH, the focus of this paper, had not been a topic of their project.

Focus groups can be described as group discussions that are structured by questions and selected stimuli, such as videos, texts, photos, or newspaper articles [37]. Table 2 shows the content and the provided materials of the focus groups in this study. A pretest served to test the intelligibility of the questions and the stimuli, the time frame, and the technical set-up of the focus groups. All focus groups were recorded by video and audio. Afterwards the material was anonymized, transcribed, and analyzed by qualitative text analysis [38]. Within this analytical method, inductive as well as deductive categories can be used to structure the material. The terms of the categories in Section 4.1 are very close to the original wording of the participants and can thus be described as “natural categories”. As a contrast, the categories of the results in Section 4.2 are analytical, which were derived from the literature review.

Table 2.

Structure of the focus groups.

The article will first present the results of Session 1, Phase 1.a (associations and perceptions regarding WCH) and Session 2, Phase 2.c (global distribution of WCH/reasons for the global imbalance) and 2.d. (personal attitudes towards the global distribution/nomination process).

In Phase 1.a the participants described their first associations with the term WCH, as well as their previous experience (if applicable). Subsequently, they were asked to discuss characteristics of WCH. This question aimed at the perceptions regarding the criteria of WCH, without confronting the participants with the official criteria of the UNESCO. The characteristics were written down, so that participants could get back to them and possibly adjust them in the course of the session.

One of the main themes of the second session was the imbalanced global distribution of WCH. At first, participants were asked how they imagine the global distribution (Phase 2.b). After being handed an information sheet showing the real global distribution (as of May 2017), participants debated possible reasons for the imbalance (Phase 2.c). Then, they received information on the nomination process and where asked if a more balanced global distribution of WCH should be aimed for (Phase 2.d).

For the second part of the study, which took place approx. a week after the second session, each group visited one WCH site (see Table 1). While each group from Hanover could choose a WCHS in Lower Saxony based on their interests, the students from Alfeld, Hildesheim, and Goslar visited the WCH site of their home town. On site, all participants individually explored the WCH by means of hermeneutic photography.

This research method is based on the idea of inducing photos taken by the participants into the interview process [40]. According to Harper that does not lead to “an interview process that elicits more information, but rather one that evokes a different kind of information” [41] (p. 13). By taking photos, participants are actively involved in the production of knowledge. At the same time, they have to critically reflect on their personal meanings, values, and relations by explaining their choice of motifs [42]. Hermeneutic photography thus enables participants to experience WCH Sites as a geographical place, a “space which people have made meaningful” [43] (p. 7). An unknown space becomes a holistic place once the interrelation among objects and subjects become visible. Place can contribute to an understanding of WCH as multilayered sites, consisting not only of tangible heritage, but also of intangible heritage and conflicting symbolic meanings [44].

Each participant was equipped with a digital camera. They had one hour to independently explore the site and take photos. They were asked to choose one motif representing the universal value of the site that could be used for an international photo campaign. Additionally, they had to select a motif that reflected their personal view and explain their choice in a brief text. Further explanations were given during short follow-up interviews that took place at the end of the site-visit. The written texts and the interviews were analyzed by qualitative text analysis [33] by the researcher, the participants were not involved in the analysis. Similar to the focus groups, categories were thus developed to structure the material. Since the categories had to reflect the personal meaning of the participants, they were not developed prior to the data collection, but derived from the data itself (see categories in Section 4.4). While the focus groups uncovered the perspectives of the students on WCH in general, the site visit aimed to explore individual perspectives on a specific WCHS. The comparison between the first associations with WCH (see Session 1) and the results of the hermeneutic photography further allowed students to reveal possibly changed perceptions and attitudes towards WCH.

4. Results

4.1. Associations and Perceptions Regarding World Cultural Heritage

Apart from a few exceptions, the participants’ views on World Heritage can be summarized as monumental and focused on the past. In their first associations, participants emphasized different types of WCH, mostly mentioning buildings and monuments. Accordingly, the most well-known sites included the Pyramid Fields from Giza (mentioned in seven groups), the Colosseum as part of the Historic Centre of Rome (five groups), and the Cologne Cathedral (four groups). WCHS representing heritage of the 20th century, archaeological findings, or cultural landscapes were hardly known among the participants.

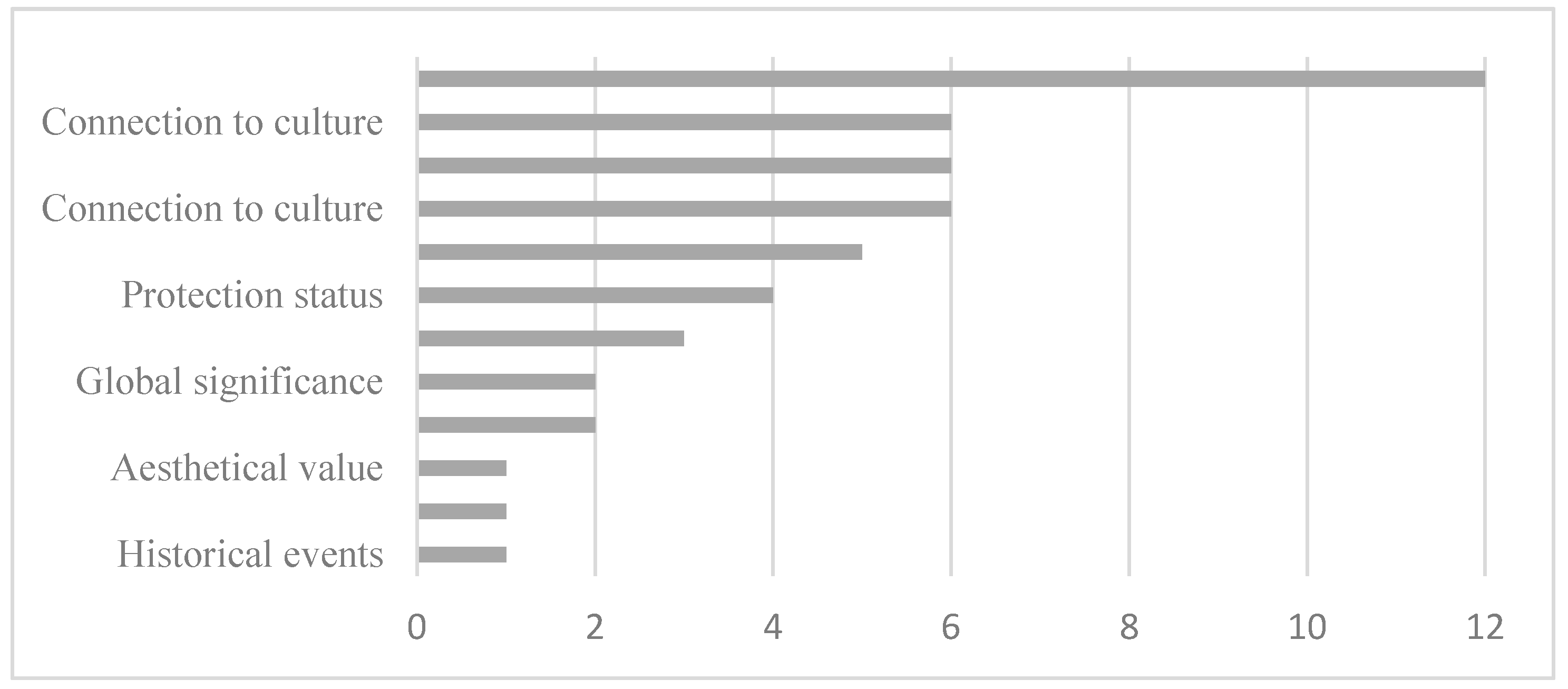

The listed characteristics for WCH underline this first impression. Figure 1 shows that the single most important factor for all groups was the sites’ significance in history. In contrast to that, only three groups requested WCH to be of relevance for the future.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of World Heritage Sites mentioned by the groups.

The connection to culture was agreed upon by six groups, who pointed out different approaches towards the understanding of culture. Participant G2_4, for example, figured that WCH is only representative for a specific community and not for a whole nation, since “not all people of a country share the same culture”. On the contrary, the perspective of G12_2 reflected an essentialist understanding of culture, according to which culture is fixed to certain spatial boundaries: “If I’m in an ancient German town, e.g., in Trier, it is rather unlikely, that I’ll find a World Cultural Heritage Site, that is a mosque. On the other hand, if you are in Istanbul, where you basically had the Islam forever, it is very likely to find one.”

Six groups agreed upon age as another characteristic of WCH and assumed that WCHS need to be “very old” (G1_2) or “not recently built” (G8_2). At the same time, some participants questioned the importance of age. One group referred to the Elbphilharmonie, a landmark concert venue in Hamburg opened in 2017, and discussed the possibility of it gaining the WCH status in the future. Of those six groups discussing the creation process, two considered that sites can be the combined work of humans and nature, while the other groups equate culture with human-made.

A comparison between the characteristics mentioned by the participants and the required criteria by UNESCO shows significant differences. The demanded OUV [1] did not seem to be of importance for the participants. Uniqueness was mentioned by five groups only, and even less groups (two) agreed upon global significance as a characteristic of WCHS. One group explicitly decided against this factor, as it was perceived as the result and not the prerequisite of the WH status. In order to be assigned with the OUV, WCHS also have to meet the conditions of integrity and authenticity (ibid., 26). However, of all the participants, only one demanded that WCHS are well conserved.

4.2. Presumptions Regarding the Global Distribution of World Cultural Heritage

The participants tended to presume that WCHS are mostly located in Europe and selected Asian countries, while Australia, North America, and especially Africa were associated with a low amount of sites. Regarding Europe, France, Germany, Italy, and the UK were repeatedly mentioned by the participants as countries with many WCHS. Four participants did not share this view, and expected Europe to have less site then other regions. While G2_1 justified this with the destruction caused by the World Wars, group 11 considered the diversity of European cultural sites to be rather low and ascribed most sites to Asia. Five people generally assumed that Africa has a low number of WCHS. In this regard, G9_2 differentiated between North and sub-Saharan Africa, which unveiled prevailing stereotypes about the continent: “I also think more sites are located in northern Africa. Because in former times, the cultures there were perhaps a bit more developed than is sometimes the case in Central Africa. Where there is sometimes no civilization at all.” Seven participants made assumptions about North America and mostly assumed that there are relatively few WCHS located there. Furthermore, six participants assumed that WCHS are distributed around the world. G5_4 doubted an even distribution of listed sites, but was convinced “that everywhere things can be found that are worth bearing this title.”

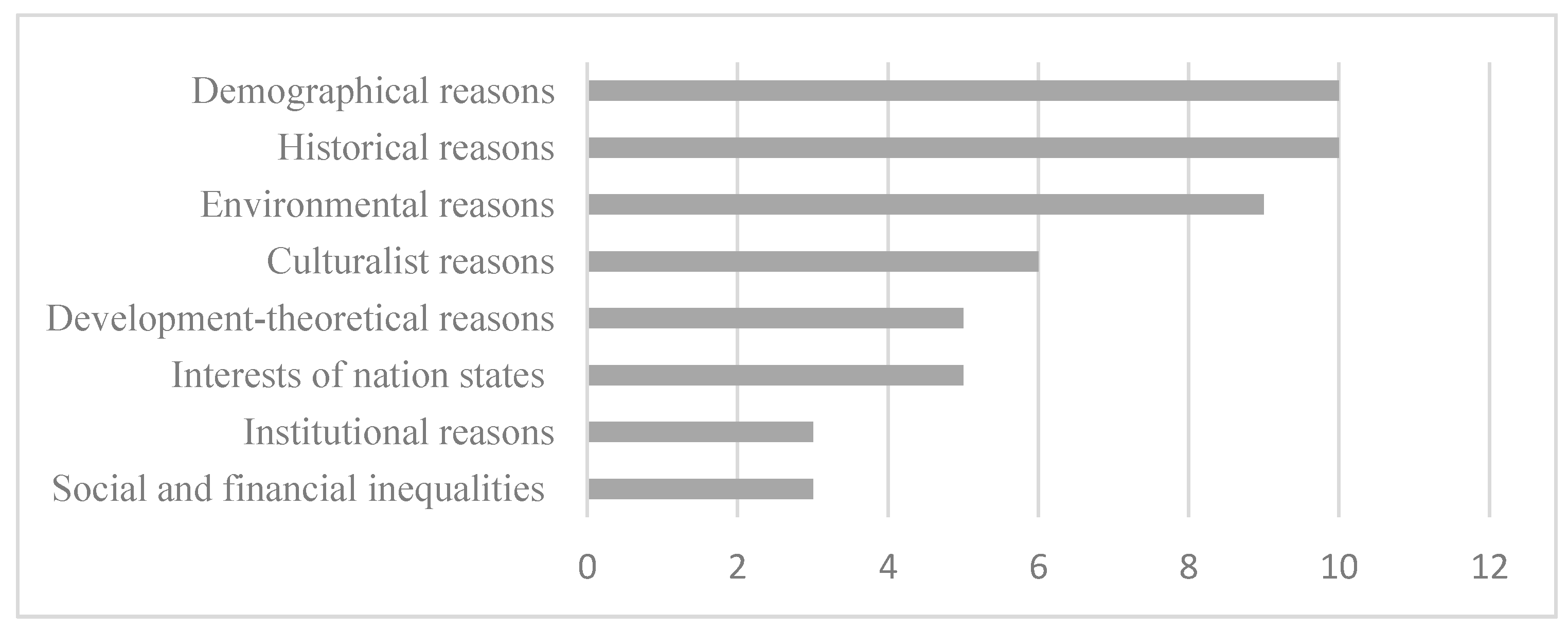

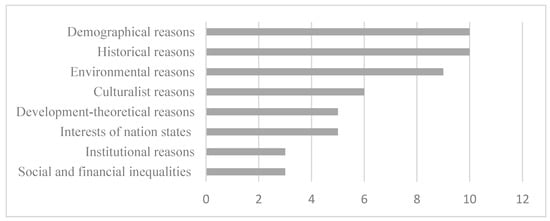

After receiving information on the actual global distribution, the possible reasons for the imbalance were discussed by the participants. Despite group-specific differences, the presumed reasons for the imbalanced global distribution of WCH showed cross-cutting tendencies. Decisive for the assumptions of most participants was the idea of Europe as an outstanding haven of culture, history, and progress. As shown in Figure 2, the groups predominantly referred to demographic, historical, and environmental reasons, while power relations (institutions, and social and financial inequalities) were mostly neglected.

Figure 2.

Reasons for the imbalanced global distribution mentioned by the participants.

Demographical reasons included duration of settlement, population density, ethnical diversity, and migration. For example, participant G10_1 assumed, “that there is less World Cultural Heritage in Australia and America, because humans haven’t lived there as long as in Europe or Asia.” Participants commonly placed WCH in large cities. Following this logic, in vast countries such as Russia and Canada, the comparatively small amount of heritage sites was justified with the low population density.

Ten groups stated reasons for the imbalance that refer to history. As shown earlier, according to the participants, the historical significance is the most important criteria for WCH. It was thus argued that the distribution is related to “historic facts” (G10_2). Areas and civilizations that were described as historically important included Egypt, China, the Aztecs and Incas, the Osman Empire, Europe in general, and Greece and Germany in particular. On the contrary G7_4 claimed that “not much happened” in Africa. Similarly, G8_2 expected WCHS in Africa to be built by “the British and French”. These quotes are exemplary for many statements that described colonization as a stimulus for cultural advancement, neglected African history, and put Europe in the center of history.

Environmental reasons focused on climate, characteristics of the natural habitat, and natural resources. According to the participants, climate influences the creation, preservation, and discovery of cultural heritage. Countries such as Russia, Canada, and Greenland were described as “bad living habitats” (G6_4), where low temperatures and ice reduce the possibility to build something “special” (G3_3) or discover archaeological findings. Likewise, G12_2 used climate and vegetation zones to explain the amount of WCHS in Africa. She claimed that “because there is so much desert, there can’t be many buildings.” It becomes obvious, that the perceptions of WCH (“buildings”) also influences the stated reasons for the imbalanced global distribution.

Culturalist approaches substantiated the distribution of WCH with different ways of life and alleged different attitudes towards cultural heritage. Aborigines in Australia, “nomadic tribes” (G5_4) in Alaska and Siberia, or “primitive tribes” in Latin America were described as nature-oriented cultures, that “did not have the leisure to build World Cultural Heritage” (G3_2). According to the participants, many sites in Africa, Asia, and Latin America are related to religion and belief systems. A further assumption was that preservation and conservation is highly valued in Europe. G11_1 contrasted this assumption to China. There, G11_1 assumed, “it doesn’t matter if something is torn down. Well, maybe it matters, but there will be less resistance than in Europe.”

Development–theoretical reasons use the development path of the Global North as a benchmark and explain the comparatively low amount of WCHS in the Global South with an alleged lack of development. For G2_4 it was “obvious” that people in Central Africa “do not just build something like the Cologne Cathedral” due to lacking financial means. Furthermore, education was perceived as a requirement for the creation, conservation, and appreciation of cultural heritage. According to the participants, the number of WCHS is also influenced by technical and industrial progress in the past, which were attributed to Europe, East Asia, and the Middle East. In this context, G9_3 compared ancient Greece to the indigenous populations of the Unites States. While “advanced mathematical skills” are ascribed to Greeks, she assumed that the native Americans only had “limited means”.

Five groups considered the interests of nation states as a factor that influences the “search” for potential WCHS and the willingness to nominate sites, as well as the commitment to the UNESCO. G8_2 assumed that Russia has a historical lack of interest in WCH, “because they have always been separating themselves. Just like they did with the wall in Germany.”

Institutional reasons were discussed by three groups. According to group 4, the decision-making process plays a crucial role. While G4_2 suspected European Member States to misuse their power to enforce their own interests, G4_1 believed in the neutrality of the UNESCO.

Insufficient financial means are a form of social inequality and were debated by two groups. Group 5 was of the opinion, that lacking financial means hinder poor countries from submitting nominations, although potential sites do exist. G4_2 also suspected that especially European countries have the financial means to carry out conservation work. Furthermore, G12_2 pointed out the discrimination of the indigenous population in the United States and its effects on current appreciation of their cultural heritage.

4.3. Attitudes towards the Imbalanced Distribution of World Cultural Heritage

Of the 43 participants, 32 expressed a personal attitude towards the distribution disparities. Five participants supported actions that contribute to achieving a more balanced global distribution of WCH. For example, participant G5_4 argued that the global imbalance might confirm stereotypes by directing the attention to selected “things, places and regions”. According to G5_4, every region should receive the same attention.

The majority of the 15 participants who were against direct actions countering the imbalance referred to the outstanding significance of WCH. Participant G9_1 recognized the global imbalance but saw no necessity for change. G9_1 was of the opinion that the amount of WCHS is a justified reflection of the greatness of a given culture. G4_2 assumed that a state might not have the financial means or cannot fulfil all the necessary criteria. Regardless of these considerations, G4_2 judged a balanced distribution as unfeasible, since the UNESCO is a “big institution”, against which protests are “incomprehensible”. Similarly, G4_1 was against any measures, since a country might just “not have anything worth a nomination”. If a balanced distribution was the ultimate goal, the requirements for the nomination might decrease and the WH title would in turn lose its prestige. G1_3 held the Member States accountable for the imbalanced distribution, as they are responsible for the nomination. If a state refrains from nominating sites, it was considered their “own fault”.

Among the 12 participants who had an ambivalent attitude towards countering the global imbalance, similar arguments prevailed. G11_2 was not generally opposed to any actions, but stressed that “it depends what a country has to offer. Europe has a lot World Cultural Heritage because of religion, but Africa is more or less just prairie, there is not much to find.” G12_2 suspected that some Member States might lack the capability to nominate sites and suggested direct nominations by the UNESCO. Contrasting this approach, G4_3 referred to the independence of every State. According to the participant, the WH list is not a “competition”. But as some countries might feel disadvantaged, G4_3 proposed public protests.

Overall, the most popular measure to counteract the global imbalance was the support of Member States. Of the eight groups considering these measures, most focused on monetary support. While G12_2 suggested the direct help of Member States with little financial means, G9_2 referred to the “communist idea” of the equal distribution of the available money. Furthermore, six groups discussed changes in the decision-making process. The transfer of power from Member States to the UNESCO or a new overarching committee responsible for nominating was presented as one possible option. In opposition to the idea of centralization, two groups suggested to extend the World Heritage Committee. Increasing the transparency and legitimacy of the nomination process led four groups to suggest public participation. G3_2 proposed an online election, which would allow everyone to vote, since the public “is the culture and it might be interesting for them to be involved in the decision.”

4.4. Universal and Personal Meanings Expressed through Hermeneutic Photography

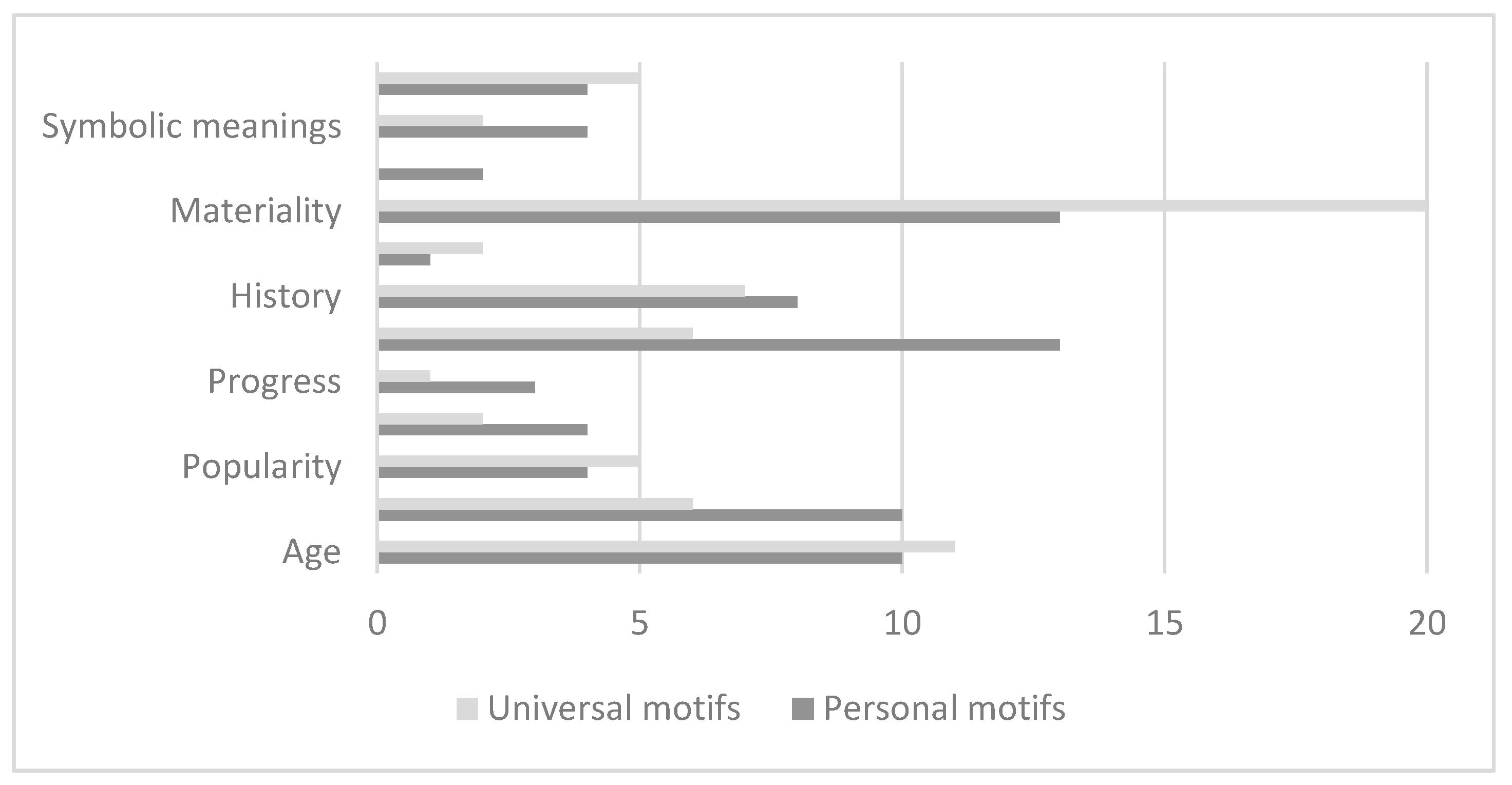

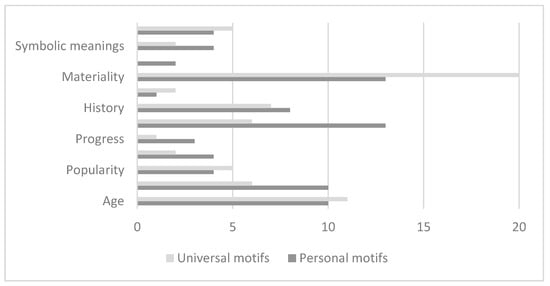

To illustrate the universal and personal meanings the participants attached to a specific WCH in Lower Saxony, their arguments supporting their motif choices were categorized (Figure 3). It is important to note that the photos could be assigned to more than one category.

Figure 3.

Categories describing the universal and personal meanings on site.

In general, it can be stated that in their justifications for the universal and personal meanings, the participants strongly referred to the associations and characteristics discussed in the focus groups. Materiality, age, aesthetics, and history were among the categories with which the choice of motif was most frequently justified. This applied in particular to the universal motifs, which were often linked to the materiality (building material, architecture, size, craftmanship) of the WCH sites. In terms of the personal motifs, no category stood out conspicuously, so that the approaches of the participants could be described as more diverse compared to the universal motifs. What was generally striking, was the dominance of individual buildings and the almost constant absence of humans on the motifs. Of all 80 photos, only three showed humans, while 32 showed an exterior view of a building. Here, differences between the students from Hanover and students from a WCH city could be noticed. Of those 32 motifs showing an individual building, 21 were submitted by the students from a WCH city. While 15 students from Alfeld, Goslar, and Hildesheim opted for a building as a universal motif, only six from Hanover did so. It can be assumed that students from a WCH city were very familiar with the imagery of the local WCH sites and could thus easily rely on their knowledge.

The category “present time” pointed to changed attitudes and values explored in the focus groups. Although the historical meaning of the site was still referred to, the present uses and meanings played a greater role for many participants during the visit, in contrast to the associations during the first focus group session. This was particularly true with regard to personal meanings. Here, participants, for example, referred to the continuous use of the site, possible employment, school, leisure time, but also to the absence of the WH title in their everyday perception.

The analyses of the images and corresponding explanations also showed that changed perceptions and attitudes were occasionally expressed on an individual level, be it with regard to the local WCH site, the UNESCO or understandings of other religions. The participants from Alfeld, Hildesheim, and Goslar also repeatedly commented that they had, for the first time, perceived the respective place as WCH. It is reasonable to assume that this changed perception can be attributed to the research method used and the restriction to one personal and one universal motif.

The following motifs by participant G5_3 were taken in the Old Town of Goslar and serve as an example for the personal reflections on site.

The motif of participant G5_3 (Figure 4) can be seen as a continuation of her reflections during the focus group. At the beginning, the participant associated WCH with touristic sights. After presenting the Andean Road System, however, she (G5_3) made everyday references to today’s infrastructure. Her motif clearly stood out, as she (the participant) explicitly was not searching for the outstanding aspects of the WCH. Instead, G5_3 emphasized that her motif showed “people just walking around in the Old Town”. In addition to this first focus on the present and the ephemeral, G5_3 further pointed to the permanent elements, such as the buildings. The participant described the variety of the materials and the designs and summarized their similarities with their “somewhat older appearance”. G5_3 stated that “in general everything here is World Cultural Heritage”, and thus justified her the chosen motif of the everyday street scene.

Figure 4.

Pedestrians in the Old Town of Goslar (universal motif by participant G5_3).

The personal motif was characterized by the fact that G5_3 was the only participant in Goslar who explicitly addressed the juxtaposition of different traces of time. Already in the reflections on the universal motif, it was evident that the participant was concerned with the relationship between old and new. While the expressed ideas about WCH at this point were shaped by the dichotomy old–new (“older buildings” vs. “modern shops”), G5_3 broke this division with the personal motif, that showed a building with a reconstructed corner tower (Figure 5). This element drew the participant’s attention to the complexity of the WCH site: “The ‘old town’ is characterized by old buildings and cultural sights (churches, monasteries and more). But you can also recognize today’s modernity.” For G5_3, the metal tower symbolized that “we live today, but there are still many things from the past by which we are very much influenced. This shows that the structure is old and full of history, but at the same time new and modern.”

Figure 5.

Mix of old and new architecture in the Old Town of Goslar (personal motif by participant G5_3).

5. Discussion

The selected results suggest that the perceptions regarding WCH and its global distribution are predominantly grounded in Eurocentric world views. While the data collection of this study was limited to Lower Saxony, its results correspond with studies that go beyond WCH and were conducted in other geographical contexts. Within the following discussion, the results are thus related to (students’) perceptions on, for example, global political hierarchies, history, or the Global South and photo-based research at other WCHS.

The perceptions of the participants show similarities to UNESCO’s early understanding of cultural heritage that has received strong critique for supporting a European understanding of heritage. Although the understanding of WCH within the scientific community, as well as the UNESCO, has since then evolved, it can be argued that in the general public discourse (in Germany) the differentiation of heritage concepts is not properly reflected [45]. The fact that most participants expressed a view on WCH that focused on monuments, buildings, and the past can thus be explained with the argument that “[a] heritage professional cannot these days go into a local community to assess the social significance of an old place without finding that the community’s expression of that significance is not in some way influenced or structured by received concepts of heritage“ [24] (p. 164).

This observation held possibly not only true for a specific heritage site, but also for perceptions regarding heritage in general. It seems that the participating young people were subconsciously referring to ideas of the AHD due to influences by media, education, or visits of WCHS. Their positionality thus needs to be accounted for. Further, the role of perceived social desirability has to be considered: do the participants mention monuments, age etc. because they think it is what the researcher wants to hear? Regarding the latter, the reflections at the end of the first session prove insightful. Here, it showed that some of the participants critically reflected on their initial perceptions on WCH. In these cases, it can be presumed that the initial statements were not aiming for the satisfaction of the researcher.

The underlying Eurocentric perceptions became especially apparent when looking at the reasons for the imbalanced global distribution of WCH. Decisive for the assumptions of most participants was the idea of Europe as an outstanding haven of culture, history, and progress, in contrast to opposing perceptions of parts of Asia, Latin America, and Africa, in particular. The use of binary opposites was considered a key concept for the understanding of the relations between the Global South and the Global North [46]. It was strongly connected to “othering”, which described how the alien “other” is created in opposition to the familiar “self” [47]. Neocolonial narratives use terms such as “primitive, savage, pre-Colombian, tribal, third world, undeveloped, developing, archaic, traditional, exotic” [48] (p. 21) to devaluate the Global South. Similarly, the participants’ statements regarding the technical progress of Europe or the achievements of historical civilizations often stood in opposition to perceptions of “African tribes living in outdated huts” (G7_3). Here, a central idea of the European understanding of modernity was apparent, which assigns different geographical areas to different stages of development. According to this linear understanding of development “Western Europe is ‘advanced’, other parts of the world ‘some way behind’, yet others are ‘backward’” [49] (p. 68). As a result, differences to the standards of the Global North are problematized, and can seemingly only be fixed through technical solutions and external help. This understanding interprets global disparities as a consequence of lacking “development” instead of unequal power relations [50]. The development–theoretical reasons of the participants, which refer to lacking knowledge and skills as well as the limited consideration of national interest and power relations, correspond to this depoliticizing approach.

Further mechanisms that maintain hegemonic structures include exoticism, deprivation of history, and essentialism [46]. Many statements concerning the Global South or the indigenous cultures of North America focus on tribes, religion, and belief; connection to nature; and rural areas. The precolonial history tends to be neglected, whereas colonialism is perceived as a cultural advancement. Especially Africa is described as historically insignificant, the only exceptions being Egypt and representations of Africa as the origin of humanity.

The negation of African history, the discrimination and simultaneous exoticism of the continent, cannot only be found in the work of European philosophers of the past [51] but still shape todays representations of Africa [52,53]. The results of this study also support previous research that has pointed out the stereotypes and prejudices of German secondary school students regarding Africa [54,55] that can certainly be linked to continuing one-dimensional and biased representations in textbooks [56].

In addition, many statements for the imbalanced distribution of WCH are grounded on environmental determinism. This paradigm dominated “western” geography in the late 19th and early 20th century and relied on climate and the environmental habitat to explain differences in behavior, cultural practices, or the “race temperament” [57] (p. 620). The resulting division of humans into groups of different abilities and intellects in turn justified repression and colonialism [58].

While a limited number of participants expressed their concerns about the imbalanced global distribution of WCH, the disparities were generally considered a minor issue. This was also reflected by the uncritical acceptance of the decision-making processes by most participants. Moreover, the selection of potential WCH as well as the final decision at the annual meeting of the World Heritage Committee were largely considered as indisputable. According to the understanding of many participants, the committee needs to merely confirm the OUV.

As the legitimacy of the decisions was only rarely doubted, most of the discussed changes to the nomination process stayed within the existing institutional framework. This included the suggestions to financially support poorer Member States, which fed from a paternalistic division in donor and receiving countries [50]. Fischer et al. [59] made similar observations in their study of the perceptions of globalization among young people in Lower Saxony, Germany. Here, the participants also rarely challenged the existing political hierarchies and decision-making processes and saw little need for comprehensive system changes. Countries of the Global North were generally described with positive attributes such a progress, freedom, and tolerance and perceived as an impulse generator for the Global South (p. 117). It has to be considered though, that the participants of the study presented in this paper were not aware about the public and scientific debate concerning the global disparities of WH. They could thus only rely on the basic information they received as well as their own assumptions.

Across both themes, a focus on history was apparent, which might be explained by the equation of heritage with history. According to Lowenthal, those two are fundamentally different. While history seeks to describe the past, “heritage is not like this at all. It is not a testable or even reasonably plausible account of some past, but a declaration of faith in that past” [60] (p. 121, emphasis in original). The understanding of heritage as a process of meaning making resulting from the act of labelling, selection, and deliberate omission [13] is thus foreign to most participants. The emphasis on the historical significance and neglect of the present might also be explained with students’ understanding of “history”. With regard to Germany, Calmbach et al. [61] have pointed out that recent events are not part of most young peoples’ concept of “history”. Moreover, history is mostly connected to museums, monuments, churches, or memorial sites.

Here, hermeneutic photography has been proven useful for reflecting existing perceptions. The method is not only a suitable research method, but also seems highly appropriate in the context of WHE. As the results show, it made sense to specifically ask for a universal and personal motif, as this enabled participants to become aware of different ways of perception. While the demand for universal motifs had a homogenizing effect, personal motifs were significantly more heterogeneous. The focus on buildings and the relative absence of people on the photos corresponds with the results of previous studies. In the study of different perceptions of the Old Town of Porto, Santos [62] examined four different point of views, including the official representation of Porto by the city administration. When searching for a universal motif, the participants took on a similar role, so that the results are particularly suitable for comparison. According to Santos, the city administration also portrayed Porto as a “city made up of monumental fragments of history: a series of architectural bodies disembodied from the city itself” (p. 133). At this point, reference should also be made to Cutler, Doherty, and Carmichael [63], who found that the photos of visitors to the Machu Picchu World Heritage Site hardly showed any other people, so that the photos give an undisturbed and timeless impression of the ruin city. Many of the universal motifs taken by the participants also coincided with the way in which the visited WHS are shown on the official website—in the illustration of the Fagus Factory and the St Mary’s Cathedral and St Michael’s Church at Hildesheim, people are completely omitted [64,65]. The fact that the submitted universal motifs were very similar to the motifs of UNESCO and actual advertising campaigns suggests that the participants were familiar with the official imagery. The described differences between the universal and personal motifs thus point towards a potential of the method. Within WHE, the hermeneutic photography might be used to uncover similarities and possible contradictions between the assigned “outstanding universal value” and everyday perceptions and thus facilitate debates about the social construction of cultural heritage.

In further studies on this topic, it would be advisable to include WCH as well as World Natural Heritage and to extend the geographical scope to other parts of Germany and beyond. If, for example, various European countries were included, Eurocentristic perspectives could be discussed in the relation to the content of textbooks and curricula of different countries.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents and discusses selected results of a qualitative study exploring WCH from the perspective of young people. In the analysis of the perceptions of the participants on WCH and its imbalanced global distribution, we have observed a domination of Eurocentric lines of reasoning. The described challenges are not only relevant in the context of WHE, but for education in general. The results and discussion reveal how important it is to foster critical thinking competency and self-awareness competency as key competencies for sustainability and for achieving the SDGs. Amongst others, these competencies “represent what sustainability citizens particularly need to deal with today’s complex challenges“ [6] (p. 11). A critical and reflexive WHE can contribute profoundly to these aims of ESD for 2030. With regard to the two approaches outlined by Vare and Scott [8], the results thus confirm the necessity to combine the approaches of ESD 1 and ESD 2. Following this understanding, creating awareness for WH and its protection is one, but not the only objective of WHE. Instead, challenging the dominating Eurocentric thinking patterns should be a major concern of WHE. Currently, the educational resources known to the authors fail to address the critical issues of WCH. While an incremental shift to a more inclusive understanding and management of WCH has taken place, the educational resources do not reflect these reforms. The critique that the UNESCO and the WH programme received in the past, largely by postcolonial scholars [66], should not only be a matter of internal or academic discussion, but explicitly be included in WHE.

For inducing reflexive thought processes and empowering learners to question the ways they and other people see and think about WCH hermeneutic photography seems promising. The participants were given the chance to reflect retrospectively on the exchange of perceptions during the focus groups and to discover multiple perceptions on specific WCH sites. With regard to the aims of ESD, the method may contribute towards action-oriented and transformative learning based on a learner-centered approach.

A critical and reflexive WHE can be based upon the experiences by scholars and practitioners of critical and reflexive learning approaches. Martin [67] reminded us that intragenerational equity (spatial equity) is a core element of sustainable development. Referring to decolonial Global Citizenship Education [68,69] Martin demanded a drastic shift in education, which includes a “move from a universal view of knowledge, to an understanding that knowledge is socially, historically, culturally constructed. Similarly, move from a view of knowledge that is certain and unproblematic, to one that reflects a relational, multiperspectival understanding concepts such as culture, identity, space, place, interdependence, sustainability—knowledges, not knowledge; futures, not future; geographies, not geography; histories, not history” [67] (p. 220).

In the words of Tlostanova and Mignolo [70] (p. 3) “it is time to start learning to unlearn […] in order to relearn” as colonial knowledge systems still subconsciously structure the mindset of many people in the Global North. Mignolo [71] further offers a helpful critique of the term “universalism”, which is of crucial importance in the context of WH. His rejection of the term did not stem from an inclination to cultural relativism, but is based on the argument that the universalisation of experiences, as proclaimed by colonialism and imperialism, is not feasible.

To conclude, we call for a WHE that puts developing an awareness for one’s own perception of heritage and reflecting upon how this understanding is tied to a specific local context at its core [72]. Educational activities and learning resources should:

- Uncover and deconstruct Eurocentric thinking patterns and integrate post- and decolonial approaches;

- Question the interests and working procedures of the involved stakeholders in the context of WH;

- Understand heritage as the result of a cultural social process influenced by power relations and national interests;

- Include reflexive approaches to evoke personal meanings of and connections to WH.

It needs to be stressed, that these aspects have no claim for completeness, rather they should be regarded as consequences of this study. Since the focus was purely on young people’s perceptions of WCH, no conclusions can be drawn regarding the interpretation of World Natural Heritage. Naturally, a critical and reflexive WHE should include World Cultural and Natural Heritage, as well as intangible heritage. Moreover, critical and reflexive WHE obviously has to be embedded in the particular context and depends on the involved actors. It has to be assumed, that different priorities are set at WHS than in the school context. However, it would be desirable if learning processes also involve critical discussions of the WH programme and educational activities at specific sites induce reflexive thought processes using methods like hermeneutic photography.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M. and V.R.; methodology, C.M.; formal analysis, V.R.; investigation, V.R.; resources, V.R. and C.M.; data curation, V.R.; writing—original draft preparation, V.R., C.M.; writing—review and editing, V.R. and C.M.; visualization, V.R.; supervision, C.M.; project administration, C.M.; funding acquisition, C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Science and Culture of Lower Saxony, grant number 76ZN1534 (VWVN 1357).

Acknowledgments

The publication of this article was funded by the Open Access Fund of the Leibniz University Hanover.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly 70/1. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1 (25 September 2015). Available online: https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/70/1 (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- UNESCO. Policy for the Integration of a Sustainable Development Perspective into the Processes of the World Heritage Convention; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Framework for the implementation of Education for Sustainabel Development (ESD) beyond 2019; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Von Schorlemer, S. The Sustainable Development Goals and UNESCO: Challenges for World Heritage. In UNESCO World Heritage and the SDGs—Interdisciplinary Perspectives (Special Issue 1 of the UNESCO Chair in International Relations); von Schorlemer, S., Maus, S., Schmermer, F., Eds.; Technische Universität Dresden: Dresden, Germany, 2020; pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- UNESCO. UNESCO Roadmap for Implementing the Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vare, P.; Scott, W. Learning for a Change: Exploring the Relationship Between Education and Sustainable Development. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 1, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R. What is Heritage? In Understanding the Politics of Heritage; Harrison, R., Ed.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2010; pp. 5–42. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, W. Cultural Diversity, Cultural Heritage and Human Rights: Towards Heritage Management as Human Rights-Based Cultural Practice. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2012, 18, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, T. Beyond Eurocentrism? Heritage Conservation and the Politics of Difference. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2014, 20, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Expert Meeting on the ‚Global Strategy‘ and Thematic Studies for a Representative World Heritage List; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1994; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/global94.htm (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Heritage List Statistics. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/stat (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- UNESCO. Progress Report, Synthesis and Action Plan on the Global Strategy for a Representative and Credible World Heritage List; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Strasser, P. “Putting Reform Into Action”—Thirty Years of the World Heritage Convention: How to Reform a Convention without Changing its Regulations. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2002, 11, 215–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskell, L. A Future in Ruins. UNESCO, World Heritage and the Dream of Peace; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rieckmann, M. Learning to transform the world: Key competencies in Education for Sustainable Developmen. In Issues and trends in Education for Sustainable Development; Leicht, A., Heiss, J., Byun, W.J., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018; pp. 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and World Natural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Dippon, P. Lernort UNESCO-Welterbe: Eine Akteurs- und Institutionsbasierte Analyse des Bildungsanspruchs im Spannungsfeld von Postulat und Praxis; Selbstverlag des Geograpischen Instituts der Universität Heidelberg: Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Heritage Education Programme. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/wheducation/ (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Deutsche UNESCO-Kommisson e.V. Resolution der 66. Hauptversammlung der Deutschen UNESCO-Kommission, Hildesheim, 28. und 29. Juni 2006. Available online: http://www.unesco.de/infothek/dokumente/resolutionen-duk/reshv66.html (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Bernecker, R.; Eschig, G.; Klein, P.; Viviani-Schaerer, M. Die Idee des universellen Erbes. In Welterbe-Manual. Handbuch zur Umsetzung der Welterbekovention in Deutschland, Luxemburg, Österreich und der Schweiz, 2nd ed.; Deutsche UNESCO-Kommisson, Luxemburgische UNESCO-Kommisson, Österreichische UNESCO-Kommisson, Schweizerische UNESCO-Kommisson, Eds.; Deutsche UNESCO-Kommisson: Bonn, Germany, 2009; pp. 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, D. Heritage Conservation as Social Action. In The Heritage Reader; Fairclough, G., Harrison, R., Jameson Jnr, J.H., Schofield, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 149–173. [Google Scholar]

- Coombe, R.J. Managing Cultural Heritage as Neoliberal Governmentality. In Heritage Regimes and the State; Bednix, R., Eggert, A., Peselmann, A., Eds.; Göttingen University Press: Göttingen, Germany, 2013; pp. 375–387. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, A. (Ed.) Lernwege zum Welterbe. Die Augsburger Wassertürme als außerschulischer Lernort; Universität Augsburg: Augsburg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thierfeldt, F. Raumordnung und Nutzungskonflikte—Das Beispiel Windenergie. In UNESCO-Welterbe Oberes Mittelrheintal; Pädagogisches Landesinstitut Rheinland-Pfalz: Bad Kreuznach, Germany, 2014; pp. 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Welterbe und Tourismus. Available online: https://denkmal-aktiv.de/wp-content/uploads/umat2010/C8.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- UNESCO. World Heritage in Young Hands. To Know, Cherish and Act; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bayerische Landeszentrale für Politische Bildungsarbeit; Zentrum Welterbe Bamberg (Eds.) Expertenspiel—Der Weg Augsburgs zum UNESCO-Welterbe. In Welterbe.Elementar; Bayerische Landeszentrale für politische Bildungsarbeit: Munich, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Österreichische UNESCO-Kommission. Welterbe für Junge Menschen Österreich. Ein Unterrichtsmaterial für Lehrerinnen und Lehrer; Österreichische UNESCO-Kommission: Vienna, Austria, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- De Cesari, C. World Heritage and mosaic universalism. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2010, 10, 299–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ströter-Bender, J. Einleitung. In World Heritage Education. Positionen und Diskurse zur Vermittlung des UNESCO-Welterbes; Ströter-Bender, J., Ed.; Tectum: Marburg, Germany, 2010; pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Silbermann, N.A. Heritage Interpretation as Public Discourse. Towards a New Pardigm. In Understanding Heritage. Perspectives in Heritage Studies; Albert, M.-T., Bernecker, R., Rudolff, B., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Röll, V.; Meyer, C. World Cultural Heritage from the Perspective of Young People—Preliminary Results of a Qualitative Study. In Heritage 2018: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Heritage and Sustainable Development; Amoeda, R., Lira, S., Pinheiro, C., Zaragoza, J.M.S., Serrano, J.C., Eds.; Green Lines Institute for Sustainable Development: Granada, Spain, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 1091–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Niedersächsisches Kultusministerium. Kerncurriculum für das Gymnasium Schuljahrgänge 5–10. Erdkunde; Niedersächsisches Kultusministerium: Hanover, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Text. Analysis A Guide to Methods, Practice and Using Software; Sage: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Welle. Syriens Zerstörtes Kulturerbe. 2014. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EyzOU18wzqA (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Rose, G. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials, 4th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, D. Talking About Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation. Vis. Stud. 2002, 17, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirksmeier, P. Zur Methodologie und Performativität qualitativer visueller Methoden—Die Beispiele der Autofotografie und reflexiven Fotografie. In Raumbezogene Qualitative Sozialforschung; Rothfuß, E., Dörfler, T., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013; pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, T. Place—A Short Introduction; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Freytag, T. Raum und Gesellschaft. In Schlüsselbegriffe der Kultur- und Sozialgeographie; Lossau, J., Freytag, T., Lippuner, R., Eds.; UTB: Stuttgart, Germany, 2014; pp. 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Strasser, P. Welt-Erbe? Thesen über das ‚Flagschiffprogram‘ der UNESCO. In Prädikat “Heritage“. Wertschöpfung aus kulturellen Ressourcen; Hemme, D., Tauschek, M., Bendix, R., Eds.; Lit Verlag: Münster, Germany, 2007; pp. 101–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft, B.; Griffiths, G.; Tiffin, H. Post-Colonial-Studies. The Key Concepts, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Spivak, G.C. The Rani of Sirmur: An Essay in Reading the Archives. Hist. Theory 1985, 24, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgovnik, M. Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. For Space; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ziai, A. Post-development 25 years after The Development Dictionary. Third World Q. 2017, 38, 2547–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegel, G.F.W. The Philosophy of History; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, F.; Griffiths, H. Power and representation: A postcolonial reading of global partnerships and teacher development through North-South study visits. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2012, 38, 907–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbembe, A. Out of the Dark Night: Essays on Decolonization; Columbia University Press: Columbia, SC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Reichart-Burikukiye, C. Wo liegt Afrika?—Das Afrikabild an Berliner Schulen. In Ethnographische Momentaufnahmen. (Berliner Blätter Ethnographsiche und ethnologische Beiträge 25); Institut für Europäische Ethnologie der Humbuldt-Universität zu Berlin: Münster, Germany, 2002; pp. 72–97. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, M. Raumwahrnehmung des südlichen Afrikas durch vernetztes Denken sensibilisieren. Prax. Geogr. 2017, 47, 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Marmer, E.; Sow, P. African History Teaching in contemporary German textbooks: From biased knowledge to duty of remembrance. Yesterday Today 2013, 10, 49–76. [Google Scholar]

- Semple, E.C. Influences of Geographic Environment: On the Basis of Ratzel’s System of Anthropo-Geography; H. Holt and Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, D.E. Environmental determinism. In Environmental Geology. Encyclopedia of Earth Science; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1999; Available online: https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/1-4020-4494-1_112 (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Fischer, S.; Fischer, F.; Kleinschmidt, M.; Lange, D. Globalisierung und Politische Bildung. Eine didaktische Untersuchung zur Wahrnehmung und Bewertung der Globalisierung; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, D. The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History, 7th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Calmbach, M.; Borgstedt, S.; Borchard, I.; Thomas, P.M.; Flaig, B.B. Wie Ticken Jugendliche? Lebenswelten von Jugendlichen im Alter von 14–17 Jahren in Deutschland; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, P.M. Crossed Gazes over an Old City: Photography and the ‘Experientiation’ of a Heritage Place. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2016, 22, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, S.Q.; Doherty, S.; Carmichael, B. Immediacy, Photography and Memory: The Tourist Experience of Machu Picchu. In World Heritage, Tourism and Identity: Inscription and Co-Production; Bourdeau, L., Gravari-Barbas, M., Robinson, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Fagus Factory in Alfeld. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1368/gallery/ (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- St Mary’s Cathedral and St Michael’s Church at Hildesheim. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/187/ (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Harrison, R.; Hughes, L. Heritage, Colonialism and Postcolonialism. In Understanding the Politics of Heritage; Harrison, R., Ed.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2010; pp. 234–269. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, F. Global Ethics, Sustainability and Partnership. In Geography, Education and the Future; Butt, G., Ed.; Continuum: London, UK, 2011; pp. 206–224. [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti, V.D.O.; de Souza, L.M.T.M. (Eds.) Postcolonial Perspectives on Global Citizenship Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sant, E.; Davies, I.; Pashby, K.; Shultz, L. Global Citizenship Education; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tlostanova, M.V.; Mignolo, W.D. Learning to Unlearn: Decolonial Reflection from Eurasia and the Americas; Ohio State University Press: Columbus, SC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, W.D. The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Röll, V.; Meyer, C. Vorstellungen von Jugendlichen über die ungleiche globale Verteilung von Weltkulturerbestätten—Didaktische Anregungen für eine kritisch-reflexive Welterbe-Bildung. GW-Unterricht 2020, 157, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).