Abstract

Sustainable rural development in Germany was examined by linking conceptual and applied aspects of the land and housing question, broadly considering the ownership, use, and regulation of land. In the state of Bavaria, a new interagency initiative aims to curb land consumption by persuading villagers to embrace rural infill development. The study explored the background debate leading up to the Space-saving Offensive (Flächensparoffensive), the resource providers involved, and the options for funding actual rural infill building and renovation projects. Here, space-saving managers and other resource providers actively promote the positive societal meaning of central infill sites in contrast to unsustainable land consumption. In addition to the communications campaign, planning, regulatory, and funding interventions round out the multi-level initiative, as described in this study. A modern barn reuse exemplifies the Bavarian bundle of resources, while demonstrating how modern village infill redevelopment also contests oversimplified notions of stagnant rural peripheries. The initiative’s focus on linking key resources and bolstering communications can be read as validation for a more social perspective on land consumption and village infill development.

1. Introduction

1.1. German Land Consumption and the Promise of Infill Development

In Germany, 56 hectares of land were consumed on average per day during the 2015–2018 time period; this generally refers to land that is converted from natural areas to various types of human land uses (from built-up homes and industrial areas to sports fields or cemeteries) and transportation land uses such as roads [1]. Spatially, land consumption is often associated with the conversion of greenfields in rural areas, while sustainable infill development/redevelopment is more commonly associated with urban areas. In Germany, the potential for infill development/redevelopment in smaller communities under 5000 residents, and especially in smaller infill parcels (in German “Baulücken”), has been highly underestimated until recently [2]. This oversight is compounded by neglecting to acknowledge rural demand for new rural development of different sizes and formats— and the need to provide this sustainably. Thus, village infill development is at once a topic with promise for countering land consumption as well as for contesting dominant preconceptions of homogenous rural conditions [3] consisting of either empty, aging peripheries or suburban-style single family housing developments. This study explored these intertwined concepts in the German state of Bavaria, situating a new policy initiative (Space-saving Offensive or “Flächensparoffensive”) within long-standing conceptual considerations of land and property, or the land question (see Section 1.2).

Rural, decentralized parts of Bavaria contribute disproportionately to land consumption, even in localized areas with stagnant economic or demographic development where one might expect less new development [4,5]. A number of underutilized planning and building instruments present options for towns seeking to further infill housing development [6], but communicating these complex options in a convincing and accessible manner to local elected officials and property owners poses a formidable challenge.

There is also the need to align development and conservation interests. Major environmental interest groups, such as the Bund Naturschutz in Bavaria (Nature Conservation Coalition) with its 245,000 members, have focused on land consumption as a root of many problems, from stormwater infiltration to sprawl. Simultaneously, many regions face an affordable housing crisis and the need to advance housing development. Thus, urban and village infill redevelopment is commonly acknowledged to be the most sustainable solution, and the target of reducing land consumption possibly presents a cross-cutting goal among divergent interest groups [7] (p. 403). The goal of reducing land consumption also avoids tricky paradoxes for policymakers around rural development, such as where rural development is ultimately heading, e.g., focused either on the most lucrative use of the land or on aesthetic values [8]. Reducing land consumption leaves what rural development is for alone and focuses on using centrally located, in-town land first.

Several initiatives, most recently the space-saving offensive (Flächensparoffensive), are working to convince rural landowners to favor town center living over greener pastures. How successful attempts will be to reduce land consumption and increase village infill development largely rests upon the bundling of resources as a concerted, persuasive effort among technical assistance and funding providers—often with a substantial dose of rural pride.

As complex human and human–nature relations construct the conditions in which land conflicts play out, this article connects conceptual considerations related to the land question with the case of the new Space-saving Offensive in Bavaria. Especially in the rural context, where the temptation to develop greenfields is substantial, this study asks: what does the Space-Saving Offensive reveal about the state’s greatest hope for success and its assumptions about how to persuade local landowners to embrace village infill development? Moreover, the case considers larger inferences and patterns related to the theoretical discussions of the land and housing question.

1.2. A Bavarian Land Question

The land question in geography aims to expose issues of ownership, use, and regulation of land generally, as well as the flow of capital across cityscapes and the socio-political ramifications [9]. The land question is not only an old question but also an intermittent one. In 1946, Bernoulli, drawing from Henry George, saw a land crisis stemming from the urban housing needs for industrialization and questioned how a community could grow and build if it does not own the land publicly. He made the prophetic recommendation for a community to “never sell any land held by it” [10] (p. 10). Scott observed that the land question “emerges” with explosive issues at critical conjunctures (e.g., property booms in capitalist cities) [11]. Furthermore, Safranksy has noted that as displacement and inequality intensify, “the land question is once again gaining urgency” [9] (p. 508).

This pattern of urgency is reflected in the current state of land conflicts in Bavaria. On one hand, there is a pressing housing need for decent, affordable urban and rural housing in different formats for families, single households, and various types of supportive and/or accessible housing. The state of Bavaria has set an annual housing unit construction goal of 70,000 units, specified in the Bavarian Ministry for Housing, Building and Transport’s Housing Offensive. Simultaneously, the need to curb land consumption has gained sufficient urgency to launch the Space-saving Offensive. Indeed, a greater Bavarian land question urgently underpins two current state offensive campaigns related to land and housing.

1.2.1. Property as a Set of Relations

Opening up property to reveal the broader societal aspects that it actively sets in motion is crucial for examining the land question as it relates to planning and village development. For instance, to what extend is land truly owned? This study draws on legal geography and the notion of property beyond mere objects of ownership, rather as “an organized set of relations between people in regards to a valued resource” [12] (p. 593). So, argues Blomley, we can see the varied and inventive ways in which property “gets put to work in the world” [13] (p. 127).

Just as various institutions and laws are involved in creating and maintaining legal private property systems (or not), so too is property made more or less feasible as an investment through a complex set of relations. Li [14] addressed the national, state and regional institutional mechanisms that “render land investable” by allowing it to be held over time (time being a key factor in investment) (p. 276). While this frequently involves the legal form of private property, it is still not absolute (ibid). Holding land may be subject to an obligation to put the land to use within a certain period of time, or to release it should new circumstances demand (ibid). What or who controls these obligations and circumstances frequently reveals societal relations. For example, Article 14 of the German constitution (“Grundgesetz”) states that property comes with duties, and its use shall also serve the community.

These understudied and understated social aspects of property within private property paradigms show that the financial and legal side of private property is only one aspect of the wider picture. From farmers to urban homeowners, attachments to the land have been shown to frequently override purely financial interests [15] (p. 19). Haila [16] explores the culture of property and the “property-minded people” in Singapore. Haila notes, “In several cultures land ownership is more than just owning a piece of real estate. People attach sentimental feelings to real property and land ownership brings prestige in addition to monetary rewards” [16] (p. 501). The concept of a culture of property also includes economic and cultural factors, such as the role of the institutions in heightening peoples’ interest in property, the propensity of different classes of people to purchase or rent property, and how their interest in property affects their views on the inevitability of change (e.g., via eviction and/or demolition) [16]. These social aspects of property are important for understanding what land policy campaigns with a specific policy intent, such as the Space-saving Offensive, assume will actually persuade property owners to act.

1.2.2. Used and Unused Property

Many programs aimed at encouraging infill development naturally focus on vacant, empty, or abandoned properties, which are classifications worth discussing. Moroni et al. [17] critically examined in the Italian context interest in so-called abandoned buildings. Whether a building is used or not and by whom it is owned play key roles in the interest or pressure to reuse the site. Distinctions should be made about empty and truly abandoned buildings, both private and public. As Moroni et al. noted [17], the existence of many abandoned buildings is due to a plurality of causes, sometimes cumulative. Local and state policies are able to address some of these causes, but not all (as with national taxation levels).

Apparent in the discussion of used and unused buildings is the social function of property. Many unused buildings become unsightly and even home to unlawful activity; this in turn affects surrounding properties. In the Bavarian context, the location of an unused building takes on special social meaning, one being actively constructed and emphasized by public officials, as centrally located unused properties become purposefully equated with furthering land consumption on open pastures. Table 1 accordingly adjusts the Moroni conceptualization for the Bavarian spatial context.

Table 1.

Buildings or Dwellings at the Owner’s Disposal.

While digital efforts to automate surveys of suitable infill properties show promise in many ways [18], they are somewhat limited in considerations of the social meaning of these properties. Additionally, it should be noted that a wide variety of sustainability arguments, in addition to preventing land consumption, such as the captured energy in existing buildings, speak for preventing building abandonment. In postindustrial U.S. Midwest cities, for instance, researchers have thus called for nuanced policies to address both merely empty buildings and truly abandoned ones, with market- and non-market-oriented interventions, as studied by Hackworth [19].

In the village setting, the social meaning of centrally located unused buildings may also feed particularly rural activist, experimental efforts to “do something”. Here the village can be seen itself as a “project” in a state of production and reproduction [20] (p. 42).

These broader discussions of property as a set of relations and the various types of unused property critically inform this study’s analysis of land consumption and infill development in rural Bavaria. In a state where land must be more sustainably used, what rights to individual property owners have to hold on to centrally located land with reuse potential? Additionally, if further limiting these rights may currently be legally or politically untenable, how can the state persuade its private and public property owners to focus more intensively on sustainable infill rural development?

2. Materials and Methods

Within the broader social context of land and property just discussed, this study asks the following research questions: What can be inferred about the social aspects of property from the state’s chosen strategies for persuading individual property owners to embrace the goals of the Space-saving Offensive? How does the state’s bundle of resources address cultural, social, and financial motivations? What types of properties in various states of use or disuse are targeted? Materially, what does an intended outcome look like? And to what extent are resource providers actively reframing the debate around rural development?

2.1. The Case Study

From a methodological point of view, the qualitative study explores an applied policy initiative through the lens of the land question discourse. This social perspective on land and property emphasizes the actors involved, the spatial context, and the socioeconomic considerations of the policy strategies pursued. This study’s analysis is thus comprised of a combination of desk research, outreach event attendance, meetings with stakeholders, e-mail and telephone correspondence with state officials and private property owners, as well as site visits and images of specific material outcomes. To build on the current state of related research, the study analyzed German and English-language academic literature related to the land question, land consumption in Germany and Bavaria, and rural infill development. Extensive federal German and Bavarian state governmental documents related to land consumption and the Bavarian Space-saving Offensive were reviewed, as well as interest group reports, media accounts, and press event proceedings mainly from the 2018–2020 time period. Practitioner and public outreach events related to land consumption and infill development were attended to some extent in-person, while additional event recordings were reviewed online. Informational program brochures from government websites provided additional details. Additionally, the study draws on stakeholder interviews conducted by master degree students towards the publication of the 2020 regional management newsletter at the Hochschule Weihenstephan-Triesdorf, overseen and edited by the author [21].

Scope

This exploratory study focuses on what understanding of property lies behind the state’s campaign, not how effective the Space-saving Offensive may in later years quantitatively prove to work in persuading them. A separate but related arm of research explores the effectiveness of myriad incentives for containing cities, such as accelerated planning processes for infill development [22]. Planning and building instruments useful for furthering infill development have been extensively and recently covered in a recent book [6] and were thus not included in the focus of this study. Likewise, financial implications from new development occurring via land consumption have increasingly come under scientific scrutiny [23]. Nationally, land tax reform is in progress and represents an important market-based intervention for furthering infill development, but these considerations fall outside this research scope.

An initial consideration in this study involved the potential scope of governmental programs to include in the analysis. The study presumes that the 2019 launch of the new Space-saving Offensive in Bavaria represents a significant coalescence of stakeholders, many of whom were already operating programs related in various ways to village renewal. Thus, this study targets the campaign’s bundling of these new and old resources, especially the funding incentives for building projects and the work of the key resource providers—effectively the persuaders. The goal of bundling resources was cited in multiple resource provider presentations, which makes the concept worth critically examining.

3. Results

The results of the study are reported beginning with an overview of the policy background and levels involved in the Bavarian Space-saving Offensive. Next, an analysis of the key resource providers and the bundle of funding incentives for public and private infill reuse and redevelopment projects is provided. The applied material outcome intended through these resources is exemplified in the case of a barn reuse project in Middle Franconia. In the subsequent discussion section, the results from this examination of the Bavarian Space-saving Offensive are related back to the theoretical framing of the study.

3.1. Overview

Widespread debate in political, spatial planning, and legal circles preceded the launch of the Space-saving Offensive. Many debates weighed which approach to take in curbing land consumption, either the immediate enforcement of strict hectare limits for new land consumption in communities or to begin with a less absolute approach towards meeting a specific goal [24]. The state chose the latter. In 2019, the state government reached an agreement to reduce land consumption with a target of 5 hectares per day to be met by 2030. By comparison, the actual daily figure in 2018 was 10 hectares [25]. The 5 hectare amount represents a compromise; prominent planning experts had called for a net zero target by 2030 [26]. (Arguably, one can wonder how anything above zero would be sustainable in the long run.) The chosen less absolute approach may either add a sense of urgency to meet the goal in order to avoid more strict limits at the local level, as largely conveyed by Bavarian media [27], or it may be seen as leniency.

Nevertheless, new and old interagency initiatives support the goal under the umbrella of the Space-saving Offensive, representing a wide bundle of funding and resource providers. It is organized in three categories: state, region, and communication (Table 2).

Table 2.

Introduction to the Bavarian Space-Saving Offensive ([28], Translation by Author).

3.2. The Bundle of Key Project Funding and Resource Providers

The Space-saving Offensive spans mainly governmental actors and governmental consortia at different geographic levels. While the initiative was spearheaded by the Bavarian Ministry of Economic Affairs, Regional Development and Energy, multiple Bavarian state governmental agencies play a role in the Space-saving Offensive. Resources were analyzed for implementing individual infill development or redevelopment projects with the aim of curbing land consumption. It is not an exhaustive list of resource providers; there are some regional differences according to the activities of individual stakeholders. Some programs existed already as the major new initiative of focus was launched. Additional resources offer community-wide assistance on planning and lot consolidation, for instance, but fall outside the realm of this research.

Resource providers on rural development and historic preservation are involved at different levels, as well as villages, cities, and municipal consortia. To varying degrees, the providers serve as points of contact for planning municipalities, intermunicipal associations, and individual property owners, and they are actively involved in outreach and public relations efforts to increase awareness on land consumption. Moreover, the infill development persuasion consists of a communications strategy as well as incentives and technical assistance. Generally speaking, the existing three pillars of rural development in Germany consist of: (1) integrated rural development through intermunicipal associations, (2) village renewal programs for public and private entities, and (3) land consolidation assistance for private and public entities [29]. The main resources explored here for infill building or restoration projects are outlined in Table 3 and explained in further detail below.

Table 3.

The “bundle” of resource providers furthering rural infill development projects in Bavaria 1.

3.2.1. Bavarian Ministry of Economic Affairs, Regional Development and Energy

As the jurisdictional home of the state’s planning program, this ministry launched the Space-saving Offensive in 2019. Many of the state-level planning objectives remain here, with extensive cooperation at regional and local levels. The initiative was quickly staffed, and supportive studies and data were made available.

Eight space-saving managers were appointed in 2019 and placed throughout the regional governments of Bavaria; some additional staff support has since been added. These managers support the Space-saving Offensive in a bottom-up and top-down manner that is typical for German land use planning processes. German planning is based on a system of reciprocal influence by federal, state and municipal authorities on each other’s proposals, or the ‘counter-current principle’ (“Gegenstromprinzip”) [30]. The space-saving managers serve as informational guest speakers at regional conferences with centrally provided uniform data, best practices, and even corporate design. They also help to plan and coordinate technical recommendations, projects, and publications supporting the initiative. In the region of Middle Franconia, Franziska Wurzinger serves as the space-saving manager. Indeed, much of the work involved in curbing land consumption involves persuasion, Wurzinger noted in a 2019 interview [21] (p. 4). Individual property owners frequently hold on to properties over time for many individual reasons, such as for their children to perhaps one day use, but these centrally located properties also represent the most sustainable options for growth, Wurzinger told a room of newly appointed village mayors in July, 2020 [31]. In one slide, Wurzinger summarized the main ramifications of land consumption for villages:

- ecological—splitting up natural areas, limiting natural soil functioning, climate change

- economic—increasing infrastructure costs per head, loss of farming areas, real estate property value losses

- social—village center degradation, longer distances to amenities, harm to the attractiveness of the landscape

This informational outreach function of the space-saving managers sets the stage for public and private property owners to then, ideally, actively pursue actual building projects. To help make infill development more persuasive in practice, Wurzinger and her colleagues from other agencies draw on a bundle of resources available for planning and building projects.

3.2.2. Regional Management Organizations

The regional management organizations have, to varying extents, prioritized the state’s Space-saving Offensive in their work. They frequently serve as partners and first points of contact for village officials and individual property owners. Bavaria’s regional management organizations are cooperative membership-based municipal consortia that encompass geographies somewhat independent of other tourist, political or cultural regions. They are involved in a broad scope of planning and project implementation based on bottom-up regional priorities, from regional economic development to bicycle networks or cooperative social services, frequently supported by the EU LEADER program for rural development.

One example of a regional management organization that is proactively involved in supporting the Space-saving Offensive is the Hesselberg Region, which actively reaches out to local village elected officials and individual property owners to educate about and encourage infill projects. Even amidst pandemic hygiene regulations in July, 2020, the region’s newly elected village mayors attended an in-person evening of presentations on the Space-saving Offensive and infill development [31]. Typically, village mayors serve as representatives to the regional management organizations; this also generally results in a ground-level connection between the efforts of the regional management organizations and potential interest among individual property members to participate in projects. However, village elections often bring out tensions between local interests for or against expanding new sites for greenfield development. Furthermore, the representatives to the regional management organizations naturally reflect current electoral trends, for better or worse, such as the age, gender, and diversity make-up of elected officials. This could also affect attitudes towards land development or interest in different types of housing formats. Thus, buy-in to the Space-Saving Offensive is not necessarily a given, but rather an ongoing communications effort.

3.2.3. Bavarian State Ministry for Housing, Building and Transportation

Within the framework of the nearly fifty-year-old federal German tradition of urban development funding (“Städtebauförderung”), the Bavarian State Ministry for Housing, Building and Transportation funds projects that advance infill development and land conservation as part of local plans, especially [32]:

- the renovation of centrally located buildings, privately or publicly owned, that are either already vacant or in danger of becoming vacant;

- the preservation of privately owned historic properties as well as other buildings that are significant for the local identity or sense of place;

- the adaptive reuse of former military industrial or commercial sites;

- conceptual planning and reports, as well as consultancy services towards local infill development and preservation in conjunction with the goals of the funding program;

- the mobilization of buildable property for communal use;

- strengthening town centers;

- the preservation and modernization of valuable historic settlements and landscapes;

- sustainable residential development, e.g., through reuse and redevelopment, energy conservation, and the improvement of soil functioning;

- mitigation of traffic impacts;

- curbing sociospatial polarization in towns and cities.

The program Inside instead of Outside (“Innen statt Außen”) is active here with communities of over 2000 residents. Funding recipients are generally municipal entities, though they may pass along funding to private recipients [33].

3.2.4. Bavarian Ministry for Nutrition, Agriculture and Forestry

Under this ministry, the Agency for Rural Development (“Amt für Ländliche Entwicklung) is home to several rural development funding sources for public and private projects. Funding for the agency’s village renewal programs stems from the European Union rural development funds as well as the state of Bavaria. Some of the ministry’s programs reach villages and larger towns, but this agency’s involvement supports the most rural areas. For instance, the Inside instead of Outside initiative (“Innen statt Außen”) in the village renewal program is active here with villages under the population threshold of 2000 residents. (Villages with a population from 500 to 2000 inhabitants are sometimes cooperatively consulted either by the Agency for Rural Development or the “Städtebauförderung”.) The initiative supports village renewal programs, including revitalization concepts, rural design and the renovation of centrally located buildings that are either already vacant or in danger of becoming vacant. The project scope for public funding recipients may include planning studies, surveys, property acquisition, building renovation/ restoration, demolition (but not landmarks), and new construction.

Funding requirements and amounts from this agency differ somewhat for private property owners, but are generally conducive to a variety of infill development or renovation projects. Notably, the different village renewal and development funding levels and funding bonuses correlate with the significance of the project’s contribution to the identity of the village (“Ortsbild”). Another funding option at the Agency for Nutrition, Agriculture and Forestry supports the farm diversification efforts of individual rural property owners (“Diversifizierungsprogramm”), classically the farmer who expands the business model to include additional revenue sources, such as vacation rentals or renovations necessary for new products. These funds are sometimes bundled with other funding programs, such as energy-saving measures.

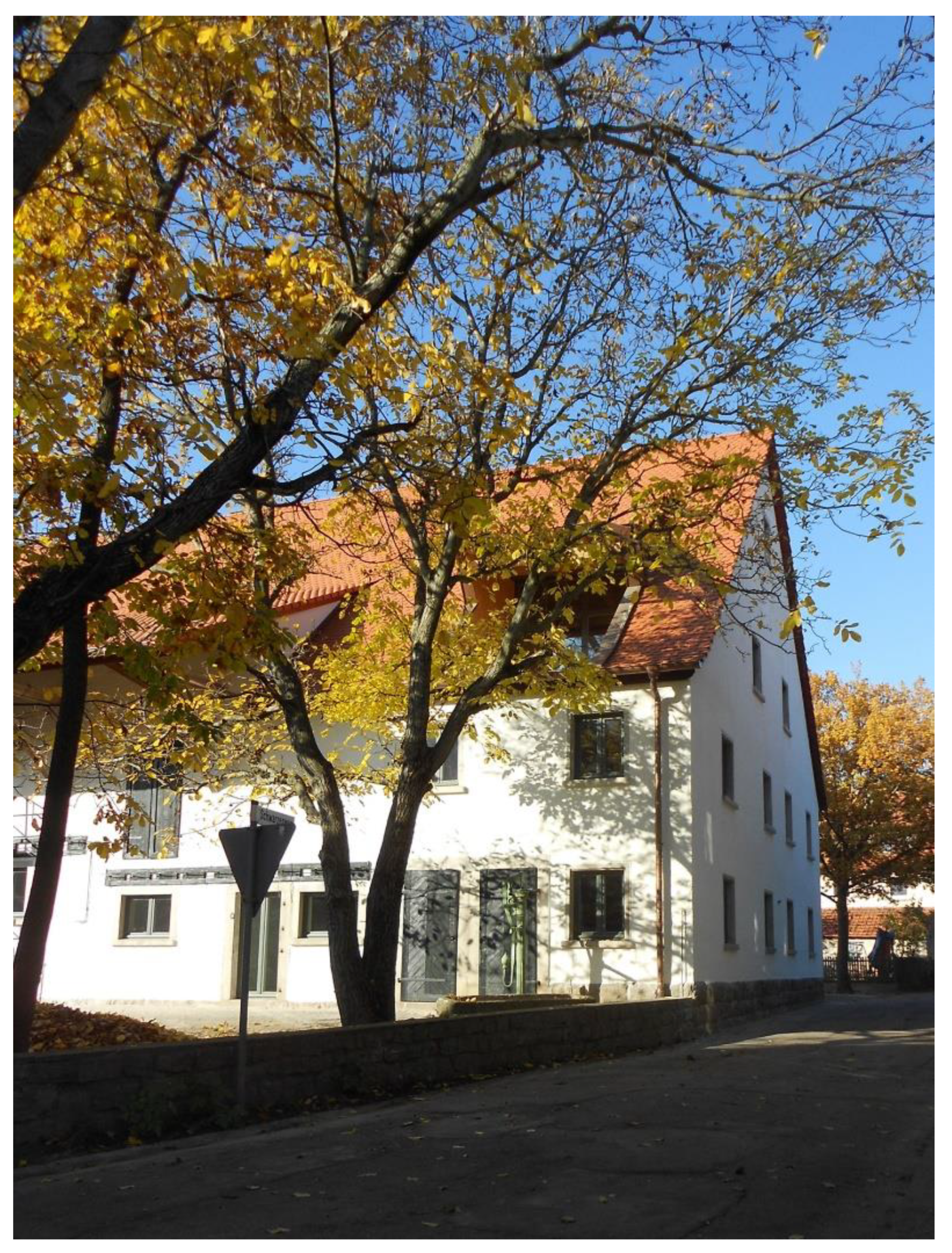

3.3. The Resource Bundle Materialized: Saving Space Through a Barn Reuse in the Village of Buchheim

Additional insights into the bundle of resources for infill development can be gained by examining the desired outcome in a material sense, such as here through the Kister family barn reuse. The village of Buchheim has a population of just over two hundred residents and belongs to the municipal consortium Burgbernheim in a very rural part of Middle Franconia, Bavaria.

Upon shifting from pig farming to focus on the agricultural fields, the Kister family barn stood empty—the family’s daughters faced the question of what to do with the aging structure. Located centrally in the village, the 1938 building (Figure 1) originally housed not only pigs but also farm workers and provided space for drying grains. One of the daughters had become a dentist, and the other an architect. The older daughter was interested in continuing both the farm (along with her father) as well as her dentistry practice, the other daughter was interested in creating an architectural gem out of the family property. Thus, the idea for the “Dentistry in the Barnyard” (“Zahnarzt im Hof”) was born, consisting of space for the dental practice as well as the creation of housing upstairs.

Figure 1.

Barn conversion, inside the former pig stall (Source: the owner of the building Kister family).

Fortuitously, the village was actively involved in a village renewal process, one of over 1200 supported by the Agency for Rural Development [34]. As such, the Kister family received guidance on suitable funding programs for their renovation project. They qualified for a diversification grant (farming plus dentistry) at the Agency for Nutrition, Agriculture and Forestry, and the Agency for Rural Development was able to help support building costs related to the roof, barnyard, and upstairs apartment.

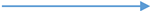

Between 2015 and 2020, planning and renovation took place on the structure, with the main floor for the dental practice and 142 m2 of upstairs space for the new apartment. Architect Andrea Kister designed the project with attention to sustainable building elements, such as the heating and insulation. The building is serviced by a local village heating source fueled by wood chips. Any necessary replacement of wood beams in the building occurred with wood supplied by the family’s own forest property. At the time of this study, the dental practice was fully operational (Figure 2), and the upstairs apartment had been recently completed [correspondence with Andrea Kister and Agency for Rural Development].

Figure 2.

Finished barn conversion with the dental practice (Source: the owner of the building Kister family).

Further material outcomes from bundling rural infill development resources via the Space-saving Offensive can be gleaned from a September 2020 written inquiry posed by the Green Party to the state legislature [35]. Best practice examples cited include the reuse of centrally located schools, barns, factories, bakeries, and military bunkers as well as the acquisition by villages of central properties for infill housing redevelopment [ibid]. The answers provided to the inquiry stress the importance of the communications and networking work of the space-saving managers to replicate these efforts. Completed material building projects become a key part of the evolving persuasion message.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Space-Saving Offensive in Perspective

This study made use of the broader discussions of property as a set of relations as well as the various types of unused property to inform an analysis of land consumption and infill development in rural Bavaria. Through this examination of the Space-saving Offensive, the following inferences could be made:

- (1)

- The political positioning of the Space-saving Offensive strategy strikes a delicate common ground among divergent interest groups, at least in a rhetorical sense. In other countries, such as Canada or the U.S., sustainable growth initiatives have focused on limiting sprawl or enforcing urban growth boundaries, but Germany’s pattern of decentralized concentration makes their challenge of preserving compact rural development somewhat different. What is more, the Bavarian goal of reducing land consumption avoids complex judgement calls on larger differences about the ultimate goals of rural development [8].

- (2)

- In practice, the Bavarian interventions included in the umbrella of the Space-saving Offensive address a variety of market and non-market measures for private and public owners, as well as used, empty, or abandoned properties, as previous researchers have implored per Moroni et al. [17] and Hackworth [19]. A broad set of social situations find their place within the bundle of resources, such as the farmer’s daughters who diversified and restored the unused barn for a modern village dental practice. Once again, many of these programs existed previously and have found new champions through the space-saving managers and additional attention to the bundling of resources.

- (3)

- The resource providers, especially the fleet of space-saving managers, are proactively accentuating the social meaning of village center sites for infill reuse and redevelopment. This strategy acknowledges the social aspects of land and property as a complex set of relationships, as per Blomley [12,13]. The space-saving manager presentations and reports relate the ecological, economic, and social aspects of land consumption for facing village mayors and property owners. For instance, particularly relevant for villagers are, on the economic side, the infrastructure savings that come from compact infill development within the existing built-up village and, on the social side, aspects of village identity that stem from attractive village centers surrounded by vital farming fields. The communications offense may also effectively serve as a sort of counter-communications to the marketing messages of large homebuilders promoting new development sites on the outskirts of villages. In a sense, the space-saving managers and other resource providers have inserted themselves into the messaging that plays a role in coproducing the social value of village center land.

- (4)

- Innovative, modern architectural reuse projects, such as the Kister family barn, actively contest dominant preconceptions of peripheral village life. As such, the Kister family barn/ dentistry practice is not only a single infill reuse project, but also part of a collective “village as project” process [20]. The resources provided by the State of Bavaria advance rural experimentation, intergenerational succession, and renewal.

In future years, the Space-saving Offensive will surely be evaluated based upon the infill projects that are undertaken and the reductions in land consumption. This study argues that the assumptions about land and property that lie within the Space-saving Offensive are as worthy of our attention as any future results from the Space-saving Offensive. Namely, the campaign at heart rests upon the belief that the value of property is dynamically socially constructed, and that the state must insert itself into this process in order to curb land consumption.

4.2. Limitations of The Study, Topics for Future Research

This exploratory study addresses the theoretical and policy background as well as the launch of the Space-saving Offensive. By nature of any offensive initiative, its duration remains unclear. Additional research should follow the achievements, setbacks, debates, and ultimately, the closing of the Space-saving Offensive. One critical quantitative measurement of its effectiveness will be if/when Bavaria meets the 5 hectare per day land consumption target, but the initiative should also be evaluated based on the many actions set forward in Table 2. Likewise, future research could explore the infill projects undertaken during the era of the Space-saving Offensive from a variety of angles, including the effectiveness of the communications campaign on project applicants and the contribution of resulting projects to diversifying rural housing and commercial space markets. In addition, as raised by the Kister project, are the infill projects funded by the state also having an effect on the gender aspects regarding who takes over centrally located village properties for future generations?

5. Conclusions

In light of broader land question debates, Bavaria’s Space-saving Offensive presents an effort to inform and mobilize villagers around the ecological, economic, and social aspects of land consumption. It builds on a sense of rural experimentation, renewal, and development already underway, even as old preconceptions of rural decay persist. It is a test of persuasive policy, cautiously nodding to the autonomy of local municipal land use planning, while simultaneously steering state and regional planning decisively away from land consumption. Organizationally, even as a campaign, it is situated within the German tradition of spatial planning’s counter current principle. The Space-saving Offensive reveals an underlying assumption on the part of the state that land consumption and village infill development are best approached from a social context. More than just financial incentives, it devotes resources in the form of space-saving managers towards actively coproducing the value of compact village infill development. The Space-saving Offensive’s progress should thus continue to be observed by researchers from a variety of disciplines.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the resource providers contacted and especially the Agency for Rural Development (Amt für Ländliche Entwicklung) for their assistance with multiple clarifications, information, and best practice examples. The author also greatly appreciates the peer reviewers’ time and insightful remarks.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Branchen-Unternehmen/Landwirtschaft-Forstwirtschaft-Fischerei/Flaechennutzung/Publikationen/Downloads-Flaechennutzung/anstieg-suv.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Schiller, G.; Blum, A.; Oertel, H. Die Relevanz kleiner Gemeinden und kleinteiliger Flächen für die Innenentwicklung. Ein quantitatives Monitoring am Beispiel Deutschlands. Raumforsch. Raumordn. Spat. Res. Plan. 2018, 76, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinführer, A.; Reichert-Schick, A.; Mose, I.; Grabski-Kieron, U. European Rural Peripheries Revalued? Introduction to this Volume. European Rural Peripheries Revalued: Governance, Actors, Impacts; LIT: Münster, Germany, 2016; pp. 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Miosga, M.; Büchs, S.; Klee, A.; Klein, R.; Odewald, C.; Paesler, R.; Weick, T.; Zademach, H. Neuorientierung der Raumordnung in Bayern. Working paper ARL LAG Bayern, Proceedings of ARL LAG Bayern, Bayreuth, Germany, 21 February 2020. 2020; Unpublished work. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Bavarian Ministry of Economic Affairs, Regional Development and Energy. Flächensparoffensive. 2020. Available online: https://www.landesentwicklung-bayern.de/fileadmin/user_upload/landesentwicklung/Dokumente_und_Cover/Flaechenverbrauch/Faechensparoffensive-2020-01.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Brandl, U.; Dirnberger, F.; Miosga, M.; Simon, M. Wohnen Im Ländlichen Raum. Wohnen Für Alle; Rehm: München, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ritzinger, A. Flächensparen zwischen Anspruch und Wirklichkeit. Zur Rolle von Akteuren und Steuerungsinstrumenten in Dorferneuerungsprozessen. Raumforsch. Raumordn. Spat. Res. Plan. 2018, 76, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, W.T. Revisiting Rural Development: How Can We Make Rural Regions Lucrative and Attractive in a Participatory Manner? In Proceedings of the International Conference on Planning and Development held at IRDP under the theme Towards industrialization in the Global South: Making Rural Regions Inclusive, Dodoma City, Tanzania, 28–30 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Safransky, S. Land justice as a historical diagnostic: Thinking with Detroit. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2018, 108, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernoulli, H. Die Stadt und Ihr Boden. Towns and the Land; Verlag für Architektur: Erlenbach, Switzerland, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.J. The Urban Land Nexus and the State; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Blomley, N. The boundaries of property: Complexity, relationality, and spatiality. Law Soc. Rev. 2016, 50, 224–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomley, N. Remember property? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2005, 29, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.M. Rendering land investible: Five notes on time. Geoforum 2017, 82, 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.; Lehrer, U. (Eds.) Suburban Land Question: A Global Survey; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Haila, A. Institutionalization of ‘the property mind’. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2017, 41, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, S.; De Franco, A.; Bellè, B.M. Unused private and public buildings: Re-discussing merely empty and truly abandoned situations, with particular reference to the case of Italy and the city of Milan. J. Urban Aff. 2020, Bd. 5, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, R.; Meinel, G. Automatisierte Erfassung von Innenentwicklungspotenzialen auf Grundlage von Geobasisdaten—Möglichkeiten und Grenzen. In Flächennutzungsmonitoring VI. Innenentwicklung—Prognose—Datenschutz; Meinel, G., Schumacher, U., Behnisch, M., Eds.; Rhombos-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2014; (IÖR-Schriften; 65); pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hackworth, J. The limits to market-based strategies for addressing land abandonment in shrinking American cities. Prog. Plan. 2014, 90, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschewski, L.; Steinführer, A.; Mölders, T. Das Dorf und die Landsoziologie. Thesen für die weiterführende Forschung. In Das Dorf. Soziale Prozesse und räumliche Arrangements; Laschewski, L., Steinführer, A., Mölders, T., Siebert, R., Eds.; Ländliche Räume: Beiträge zur lokalen und regionalen Entwicklung LIT: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 203–207. [Google Scholar]

- HSWT. Management Regional. Available online: https://www.hswt.de/fileadmin/beuser/_LT/RM/DokumenteAllgemein/NewsletterMRM_Ausgabe_2020_01.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Dillmann, O.; Beckmann, V. Do Administrative Incentives for the Containment of Cities Work? An Analysis of the Accelerated Procedure for Binding Land-Use Plans for Inner Urban Development in Germany. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, S.; Korzhenevych, A. The effect of industrial and commercial land consumption on municipal tax revenue: Evidence from Bavaria. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kment, M. Flächenverbrauchsobergrenzen, Flächenhandelssysteme und Kommunale Planungshoheit—Eine Bayerische Perspektive. Nat. Recht 2018, 40, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landesentwicklung Bayern. Available online: https://www.landesentwicklung-bayern.de/fileadmin/user_upload/landesentwicklung/Dokumente_und_Cover/Flaechenverbrauch/Datenblatt_Flaechenverbrauch_2018.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Jacoby, C.; Job, H.; Kment, M.; Miosga, M. Begrenzung der Flächeninanspruchnahme in Bayern. Positionspapier der ARL111. Hannover. 2018 Akademie für Raumforschung und Landesplanung. 2018. Available online: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0156-01116 (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Dechant, R. Flächensparoffensive Bayern: Regionalkonferenz in Ansbach. Bayerischer Rundfunk. Available online: https://www.br.de/nachrichten/bayern/flaechensparoffensive-bayern-regionalkonferenz-in-ansbach,RfeHH7K (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Bavarian Ministry of Economic Affairs, Regional Development and Energy. Flächensparoffensive. Available online: https://www.landesentwicklung-bayern.de/flaechenspar-offensive/ (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- Bavarian State Agency for Rural Development. Available online: https://www.stmelf.bayern.de/mam/cms01/landentwicklung/dokumentationen/dateien/le_infokompendium.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Schmidt, S.; Buehler, R. The planning process in the US and Germany: A comparative analysis. Int. Plan. Stud. 2007, 12, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurzinger, F. The Space-Saving Offensive Flächensparoffensive. In Proceedings of the Lebenswerte Innenorte in der Region Hesselberg Conference, Unterschwaningen, Germany, 8 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bavarian State Ministry for Housing, Building and Transport. Städtebauförderung. Available online: https://www.stmb.bayern.de/buw/staedtebaufoerderung/foerderschwerpunkte/index.php (accessed on 17 October 2020).

- Bavarian State Ministry for Housing, Building and Transport. Available online: https://www.stmb.bayern.de/assets/stmi/buw/staedtebaufoerderung/informationsflyer_f%C3%B6derinitiative_innen_statt_au%C3%9Fen.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Bavarian State Agency for Rural Development. Available online: https://www.stmelf.bayern.de/mam/cms01/landentwicklung/dateien/le_kurzportrait_pol_auftrag.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Bavarian State Legislature. Drucksache18/9291, 18.09.2020. Available online: http://www1.bayern.landtag.de/www/ElanTextAblage_WP18/Drucksachen/Schriftliche%20Anfragen/18_0009291.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).