Stronger Impact of Interpersonal Aspects of Satisfaction Versus Tangible Aspects on Sustainable Level of Resident Loyalty in Continuing Care Retirement Community: A Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Application of the Relational Theory of Third Places in a CCRC Setting

2.2. CCRCs as Community-Embedded Third Places with Long-Duration Service Experiences

2.3. Tangible versus Interpersonal Aspects of Resident Satisfaction in a CCRC

2.4. Hypotheses Development

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

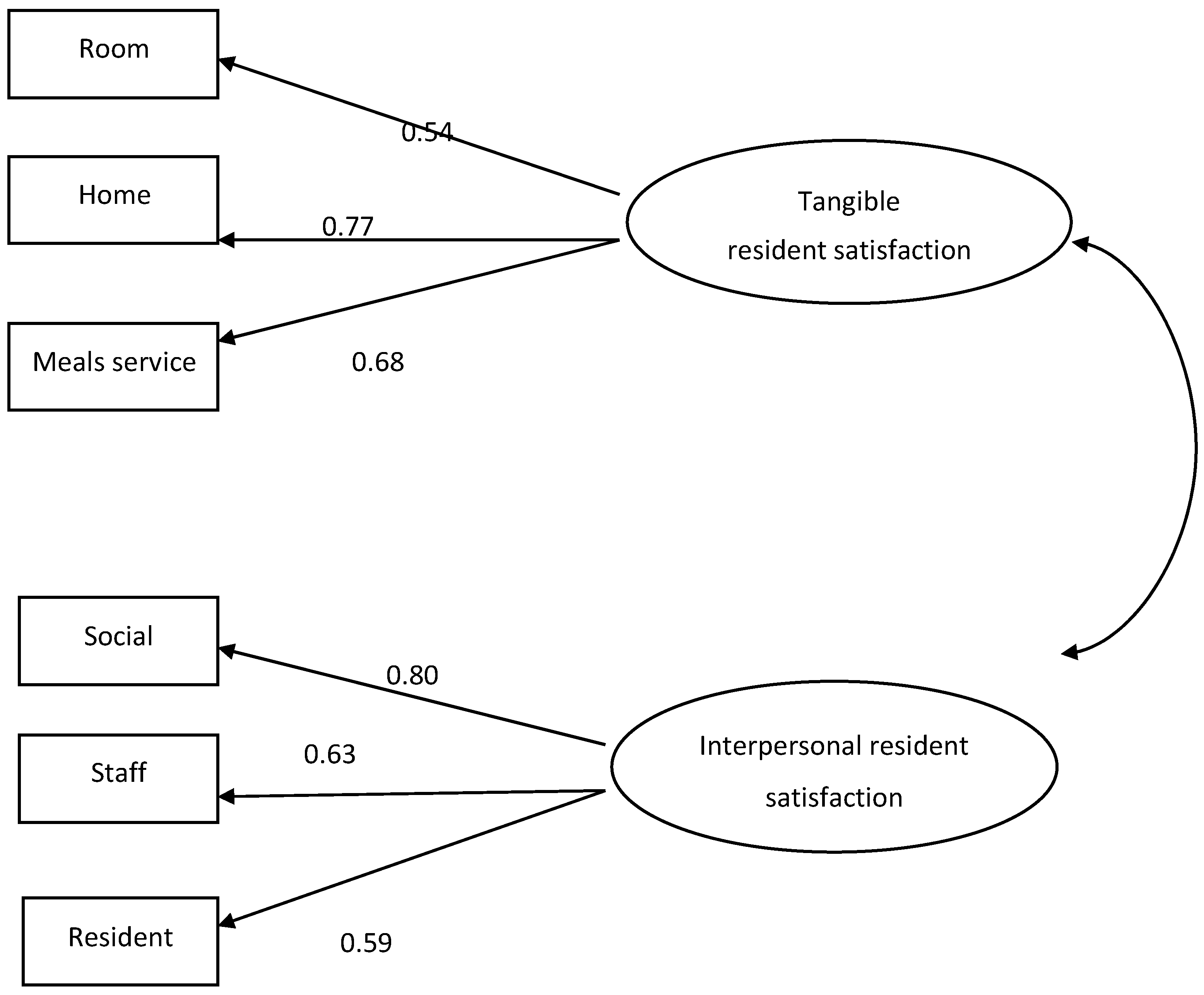

3.2. Measures and Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.2. Results of Hierarchical Regression Analysis and MANOVA

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

5.2. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Studies

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hwang, H. Intention to use physical and psychological community care services: A comparison between young-old and older consumers in Korea. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JCHS. Housing America’s Older Adults—Meeting the Needs of an Aging Population; Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- AARP. How Continuing Care Retirement Communities Work. 2020. Available online: https://www.aarp.org/caregiving/basics/info-2017/continuing-care-retirement-communities.html (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Krout, J.A.; Oggins, J.; Holmes, H.H. Patterns of service use in a continuing care retirement community. Gerontologist 2000, 40, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oldenburg, R. The Great Good Place; Marlow: New York, NY, USA, 1999; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, M.S. Exploring the Social Supportive Role of Third Places in Consumers’ Lives. J. Serv. Res. 2006, 9, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-E.; Severt, D. The Role of Hospitality Service Quality in Third Places for the Elderly: An Exploratory Study. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2017, 58, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Simpson, P.; Siguaw, J.A. Communities as Nested Servicescapes. J. Serv. Res. 2016, 20, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanford, S. Antecedents and Outcomes of Hospitality Loyalty. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2016, 57, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, M.; Poggesi, S. Servicescape cues and customer behavior: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Serv. Ind. J. 2013, 33, 171–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Ward, J.; Walker, B.A.; Ostrom, A.L. A cup of coffee with a sash of love: An investigation of commercial social support and third-place attachment. J. Serv. Res. 2007, 10, 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Krout, J.A.; Moen, P.; Holmes, H.H.; Oggins, J.; Bowen, N. Reasons for Relocation to a Continuing Care Retirement Community. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2002, 21, 236–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, D.; Eckert, J.K.; Rubinstein, B.; Keimig, L.; Clark, L.; Frankowski, A.C.; Zimmerman, S. An ethnographic study of stigma and ageism in residential care or assisted living. Gerontologist 2008, 48, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perkins, M.M.; Ball, M.M.; Kemp, C.L.; Hollingsworth, M.C. Social Relations and Resident Health in Assisted Living: An Application of the Convoy Model. Gerontologist 2012, 53, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mead, L.C.; Eckert, J.K.; Zimmerman, S.; Schumacher, J.G. Sociocultural Aspects of Transitions from Assisted Living for Residents with Dementia. Gerontologist 2005, 45, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Perkins, M.M.; Ball, M.M.; Whittington, F.J.; Hollingsworth, C. Relational autonomy in assisted living: A focus on diverse care settings for older adults. J. Aging Stud. 2012, 26, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shippee, T.P. “But I Am Not Moving”: Residents’ Perspectives on Transitions Within a Continuing Care Retirement Community. Gerontologist 2009, 49, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stedman, R.C. Understanding Place Attachment Among Second Home Owners. Am. Behav. Sci. 2006, 50, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.-C.; Boldy, D.P.; Lee, A.H. Measuring resident satisfaction in residential aged care. Gerontologist 2001, 41, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Matos, C.A.; Rossi, C.A.V. Word-of-mouth communications in marketing: A meta-analytic review of the antecedents and moderators. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 578–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivadas, E.; Jindal, R.P. Alternative measures of satisfaction and word of mouth. J. Serv. Mark. 2017, 31, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Kwortnik, R.J.; Wang, C. Service loyalty: An integrative model and examination across service contexts. J. Serv. Res. 2008, 11, 22–42. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, A.; Ramaseshan, B. Customer Referral Behavior: Do Switchers and Stayers Differ? J. Serv. Res. 2014, 18, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, N.M. Designing Retirement Community Third Places: Attributes Impacting How Well Social Spaces Are Liked and Used. J. Inter. Des. 2014, 39, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, L.C.; Glonek, G.F.V.; Luszcz, M.A.; Andrews, G.R. Effect of social networks on 10 year survival in very old Australians: The Australian longitudinal study of aging. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Groves, P.M.; Thompson, R.F. Habituation: A dual-progress theory. Psychol. Rev. 1970, 77, 419–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, S.-C.; Boldy, D.P.; Lee, A.H. Factors Influencing Residents’ Satisfaction in Residential Aged Care. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, C.M.; Kenny, D.A. Process analysis: Estimating mediation in evaluation research. Eval. Res. 1981, 5, 602–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundleby, J.D.; Nunnally, J. Psychometric Theory. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1968, 5, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson Education, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

| Construct and Scale Items | Mean (SD) | Factor Loading | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resident satisfaction | ||||

| Room (α = 0.816) | 0.888 | 0.599 | ||

| R1: Room size | 6.2 (1.0) | 0.734 | ||

| R2: Amount of storage space | 5.7 (1.4) | 0.798 | ||

| R3: Bathroom | 6.1 (1.2) | 0.789 | ||

| Home (α = 0.817) | 0.882 | 0.533 | ||

| H1: Its design for being able to get around easily | 5.7 (1.2) | 0.637 | ||

| H2: The lounge area | 6.1 (0.8) | 0.887 | ||

| H3: The dining room | 5.9 (1.1) | 0.740 | ||

| H4: The outside areas | 6.1 (1.0) | 0.624 | ||

| Social interaction (α = 0.878) | 0.932 | 0.714 | ||

| S1: Having enough things to do | 6.1 (0.9) | 0.879 | ||

| S2: Social life in this community | 6.0 (1.0) | 0.832 | ||

| S3: Being able to keep in touch with life outside | 6.2 (0.8) | 0.823 | ||

| Meals service ((α = 0.857) | 0.913 | 0.607 | ||

| M1: Variety of food | 5.6 (1.3) | 0.747 | ||

| M2: Amount of food | 6.3 (1.0) | 0.844 | ||

| M3: Temperature of food | 5.9 (1.2) | 0.875 | ||

| M4: Meal times | 5.9 (1.2) | 0.625 | ||

| Staff care (α = 0.848) | 0.913 | 0.672 | ||

| C1: Staff attitude toward residents | 6.4 (0.8) | 0.930 | ||

| C2: Their respect for residents’ privacy | 6.4 (0.8) | 0.839 | ||

| C3: The promptness with which they respond to residents’ calls for help | 6.2 (1.0) | 0.667 | ||

| Involvement (α = 0.813) | 0.900 | 0.628 | ||

| I1: Keep residents informed enough about things that may affect them | 5.7 (1.2) | 0.842 | ||

| I2: Have enough opportunities to put residents views to the management | 5.5 (1.7) | 0.806 | ||

| I3: Feel comfortable about approaching staff to discuss a concern | 5.9 (1.4) | 0.724 | ||

| WOM (α = 0.963) | 0.981 | 0.900 | ||

| W1: I will recommend this community to other people. | 6.4 (0.9) | 0.962 | ||

| W2: I will encourage other people to choose this community. | 6.4 (1.0) | 0.979 | ||

| W3: I will say positive things about this community to other people. | 6.4 (0.9) | 0.903 |

| Construct | Cronbach’s α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Room | 0.816 | 1.00 | 0.307 * | 0.229 * | 0.110 * | 0.236 * | 0.082 * | 0.089 * |

| 2. Home | 0.817 | 0.554 | 1.00 | 0.444 * | 0.310 * | 0.300 * | 0.162 * | 0.162 * |

| 3. Social interaction | 0.878 | 0.478 | 0.666 | 1.00 | 0.371 * | 0.282 * | 0.329 * | 0.343 * |

| 4. Meals service | 0.857 | 0.332 | 0.557 | 0.609 | 1.00 | 0.306 * | 0.169 * | 0.139 * |

| 5. Staff care | 0.848 | 0.486 | 0.548 | 0.531 | 0.553 | 1.00 | 0.183 * | 0.274 * |

| 6. Resident involvement | 0.813 | 0.288 | 0.402 | 0.574 | 0.411 | 0.428 | 1.00 | 0.419 * |

| 7. WOM | 0.963 | 0.299 | 0.403 | 0.586 | 0.373 | 0.523 | 0.647 | 1.00 |

| Step | Variables Entered | β | t | Sig. | R2 | F | Sig. | R2 | F Change | Sig. F Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 1 | Room | 0.089 | 1.080 | 0.282 | 0.182 | 11.334 | <0.001 | |||

| Home | 0.219 | 2.379 | 0.019 | ||||||||

| Meals service | 0.216 | 2.500 | 0.013 | ||||||||

| 2 | Room | −0.022 | −0.309 | 0.758 | 0.408 | 17.235 | <0.001 | 0.226 | 19.112 | <0.001 | |

| Home | 0.023 | 0.269 | 0.788 | ||||||||

| Meals service | 0.019 | 0.237 | 0.813 | ||||||||

| Social interaction | 0.270 | 3.085 | 0.002 | ||||||||

| Staff care | 0.233 | 3.016 | 0.003 | ||||||||

| Involvement | 0.276 | 3.674 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Model 2 | 1 | Social interaction | 0.281 | 3.710 | < 0.001 | 0.407 | 35.028 | <0.001 | |||

| Staff care | 0.237 | 3.277 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| Involvement | 0.277 | 3.733 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| 2 | Social interaction | 0.270 | 3.085 | 0.002 | 0.408 | 17.235 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.077 | 0.972 | |

| Staff care | 0.233 | 3.016 | 0.003 | ||||||||

| Involvement | 0.276 | 3.674 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Room | −0.022 | −0.309 | 0.758 | ||||||||

| Home | 0.023 | 0.269 | 0.788 | ||||||||

| Meals service | 0.019 | 0.237 | 0.813 |

| λ Value | F-Value | Sig. | Partial η2 | Observed Power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Room | 0.089 | 2.717 | <0.001 | 0.554 | 1.00 |

| Home | 0.031 | 3.095 | <0.001 | 0.686 | 1.00 |

| Meals service | 0.035 | 3.650 | <0.001 | 0.673 | 1.00 |

| Dependent Variable | F-Value | Sig. | Partial η2 | Observed Power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Room | Social interaction | 1.606 | 0.139 | 0.410 | 0.708 |

| Staff care | 4.120 | 0.001 | 0.641 | 0.995 | |

| Involvement | 0.754 | 0.698 | 0.246 | 0.341 | |

| Home | Social interaction | 3.562 | 0.001 | 0.704 | 0.996 |

| Staff care | 4.014 | <0.001 | 0.728 | 0.999 | |

| Involvement | 1.417 | 0.189 | 0.486 | 0.730 | |

| Meals service | Social interaction | 3.595 | 0.001 | 0.657 | 0.993 |

| Staff care | 5.316 | <0.001 | 0.739 | 1.00 | |

| Involvement | 0.705 | 0.767 | 0.273 | 0.343 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.-E. Stronger Impact of Interpersonal Aspects of Satisfaction Versus Tangible Aspects on Sustainable Level of Resident Loyalty in Continuing Care Retirement Community: A Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218756

Lee J-E. Stronger Impact of Interpersonal Aspects of Satisfaction Versus Tangible Aspects on Sustainable Level of Resident Loyalty in Continuing Care Retirement Community: A Case Study. Sustainability. 2020; 12(21):8756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218756

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Ji-Eun. 2020. "Stronger Impact of Interpersonal Aspects of Satisfaction Versus Tangible Aspects on Sustainable Level of Resident Loyalty in Continuing Care Retirement Community: A Case Study" Sustainability 12, no. 21: 8756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218756

APA StyleLee, J.-E. (2020). Stronger Impact of Interpersonal Aspects of Satisfaction Versus Tangible Aspects on Sustainable Level of Resident Loyalty in Continuing Care Retirement Community: A Case Study. Sustainability, 12(21), 8756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218756