Abstract

The article deals with the issue of competitive advantages based on the knowledge of Polish green-technology companies. It aims to identify the sources of knowledge and indicate companies’ competences in acquiring knowledge, which are believed to be the basis of their market success. Empirical research presented in this article was based on qualitative studies using in-depth interviews. The obtained results allowed to identify the most important sources of knowledge that can be structured into the following pillars: research and development works, knowledge on the competitors, customers and recipients, green technology domestic market, and foreign markets for green technologies. Moreover, it allowed to identify the competences of green-technology companies in Poland and describe the process of acquiring these competences. The analysis of the collected data and the obtained results allowed to create a model of acquiring new knowledge by green-technology companies in Poland, which serves as a basis for these companies to gain distinctive competences.

1. Introduction

The competitive advantage of companies based on knowledge and competence has been analyzed in management studies for a long time. The most important theoretical concepts concerning this topic include the resource-based theory, derived from strategic management, as well as knowledge management. According to Li et al. [1], the resource-based theory highlights continuous value creation functions of co-operation under accordingly varied organizational capacities and diverse organizational resources. This is done to establish innovation processes in order to combine internal inputs with external ones and to create business value leveraging [2]. According to Conchado et al. [3], knowledge of management constructs constitutes a novelty with regard to the traditional division of generic and specific competences and it is composed of learning processes and specific competences. Knowledge is dynamic and its value varies with regard to place, time, context and the manner of its use. Without these characteristics it is simply information and its meaning and value for the company is challenging to define [4]. Nevertheless, focusing on knowledge management may support companies’ ambidexterity and competitiveness [5].

Following this framework indicating the importance of time- and context-specific analyses, several contributions have been made by various authors, describing the aspects of knowledge and competences of green companies in the case of the following countries: China [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14], Australia [15], Brazil [16], Canada [17], Finland [18], Germany [19,20], India [21,22], Japan [23], Malaysia [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], Pakistan [32,33,34,35,36,37], Romania [38], Slovakia [39], Asian-Pacific area (including Taiwan, South Korea, China, Hong Kong, India) [40] and European countries (including France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom as one group) [41]. This study attempts to follow this framework and build on the research findings related to the knowledge and competences of companies (from the perspective of resource-based theory) [42,43,44] and knowledge management in organizations [45,46,47] (especially since the survival of companies largely depends on significant investments in knowledge management [48]). Although important contributions tackling the characteristics of green-technology companies based outside of the Central and Eastern European (CEE) region have been made, there are only a few describing CEE companies—e.g., [39]. Studies concerning Poland with a specific focus on green technology suppliers and their knowledge and competences are still rare [49]. Thus, this paper seeks to fill this gap and aims to identify sources of knowledge and competences in the field of knowledge acquisition and management used as resources which could account for the success of Polish green-technology companies. This empirical research focuses on:

- the identification of the knowledge and competence sources in Polish green-technology companies,

- the ways of gaining and developing identified knowledge and competences,

- assessment of the importance of identified knowledge and competences.

Moreover, it addresses the following research questions:

- What are the knowledge sources of the companies—suppliers of green technologies in Poland?

- Which of identified knowledge sources are the most important sources of knowledge for the companies operating on the Polish market?

- What type of knowledge is acquired and developed though different knowledge sources?

- What are the competences in knowledge acquisition that the green-technology companies in Poland already use?

- How green-technology companies acquire knowledge that is necessary to compete on the market?

The research sample was identified among major suppliers of green technologies in Poland. The success of selected companies was based on generating green technology innovations and their commercialization on both, domestic and foreign markets. It should be underlined here that the interrelation between innovation and trade has been a subject of research over recent decades [50]. It should be mentioned as well that green technology is understood here as a type of green product innovation, next to services, organizational structures or management modes adopted by enterprises to achieve sustainable development ([11] after [51]).

The article is structured as follows. It starts with a discussion on theoretical fundaments of knowledge and competences of companies in the light of resource-based theory and knowledge management, including the process of companies acquiring new knowledge. Then, the research assumptions, goals and research questions are presented along with the adopted research method. Finally, the research results and their significance in the light of the discussed theories of management are presented. The paper ends with concluding remarks.

2. Knowledge and Competences of Companies from the Perspective of Resource-Based Theory

Resource-based theory, as a concept of strategic management, assesses company’s success based on their valuable skills and resources, which include knowledge and competences; however, it is biased due to the companies’ ability to use the above-mentioned aspects in a certain way [42]. Representatives of this theory were focused on identification and explanation—which of the resources are stated as important to a particular company and treated as crucial when gaining competitive advantage in the particular market. According to the theory of Jay Barney, the strategic resources could be described as as valuable (V), rare (R), imperfectly imitable or inimitable (I) and not substitutable (N)—namely VRIN attributes [52] (p. 11), [43] (pp. 105–112).

Knowledge and competences of company’s employees can be classified as its strategic resources. Thanks to these two types of resources, companies can create new products, technologies and/or services, which allow them to improve their market position. The ability to develop environmentally friendly technologies can also be classified as one of companies’ strategic resources, which can bring different benefits to a company at each stage of the value chain [53] (p. 190).

Promoters of the resource-based theory, Hamel G. and Prahalad C.K., treated organizations as bundles of resources and capabilities, whose adequate use leads to development of the core competencies of a company, which then allow development of products and adjustments to the dynamically changing organizational environment and are fundamental to the company’s strategic advantage [42] (p. 11–12). The core competencies of companies include, among others, their unique skills that enable their access to various markets, affect the value of products perceived by customers and are difficult or even impossible to be copied by competitors [54] (p. 83).

Core competencies relate to the development of a company, especially to their potential of creating new product lines and technologies and expansion to new domestic and foreign markets. These competencies should not be treated as related to the final products or technology availability only. Hamel and Prahalad [54] claimed that companies should build their competitive advantage on the level of a whole organization without confining solely to the distinctive units or departments of an organization. Successful use of specific skills, knowledge and abilities of an organization to learn collectively, integrating multiple technology streams and synchronizing multiple production skills can give it significant advantages [54] (p. 81). The hierarchic structure of the resource base of a company includes core assets (having resources), operational capabilities (doing resources), competencies and core competencies [44] (p. 7).

There are many ways, through which companies acquire, create and use knowledge assets. (knowledge assets are the inputs, outputs and moderating factors of the knowledge-creating process, unique resources within the company, which help to create organizational value [14] (p. 20), [2]). From a theoretical perspective, understanding the complexity of these processes eases the categorization of the knowledge sources, according to which the empirical, conceptual, routine and general resources can be distinguished [4] (pp. 20–22). The most valuable knowledge sources are the ones that the company develops itself and other companies have no way to acquire these easily nor quickly from the organizational environment. However, it is not enough to have the right skills, competences, and capabilities. To gain a competitive advantage, companies must also constantly develop them to answer to the new requirements in terms of, e.g., competition, innovation performance, market development. In response to, among others, rapidly changing markets, the concept of dynamic capabilities was developed, which is treated by representatives of strategic management studies as supplementary to the resource-based theory [44]. It emphasizes the importance of the dynamics of the processes of creating a company’s competitive advantage by combining and co-ordinating the resources of the organization and their transformation into strategic competences, allowing for the creation of value for the client [55]. Dynamic capabilities include a company’s skills to integrate and build internal and external abilities so that it functions efficiently in a dynamically changing environment. These are also abilities to identify and shape opportunities and threats, take advantage of opportunities, maintain a competitive position on the market by increasing, combining, protecting and, if necessary, restructuring tangible and intangible assets of the company [56]. Dynamic capabilities mirror a company’s efforts to co-create and shape the market taken to strengthen its competitive position and create added value [57].

3. Knowledge Management in Organizations and Organizational Learning

The knowledge management as a complement to the resource-based approach has been researched for at least the last two decades [58] (p. 110). Such an opinion is formed by the successive editions of the research on certain issues—e.g., the complementarity and compatibility of the approach were mentioned in Maier [59] (p. 103). Moreover, Curado and Bontis [45] mentioned that a knowledge-based view of a company is an extension of the resource-based view. As the topic of knowledge-based management is still under consideration, it is worth paying attention to the article of Nagano [60] who highlighted the growth of knowledge (management) within the resource-based view framework and the need for a new framework to emerge due to knowledge-based management limitations.

The existence of knowledge in an organization is conditioned by a variety of processes, including its availability, creation, assimilation, sharing, value and management of its flows. An enterprise can acquire knowledge in different ways and from different perspectives. Research and development activities are considered to be the primary sources of valuable knowledge developed in organizations. This type of company self-activity contributes to building its absorption capacity, which in turn helps to identify valuable new knowledge in an organization’s environment even more effectively, facilitates its assimilation, and uses the new knowledge for commercial purposes [46] (pp. 128–152). Other possibilities of gaining knowledge include: organizational environment analysis, purchase of reports and analyses, market research, monitoring the activities of key entities from the point of view of their operations, employment, hired staff investments, contact with current and potential partners, competitors, clients, suppliers, distributors, advisors or even mergers and acquisitions. Important sources of knowledge on the economic environment and a particular company’s operation market may also include trade associations, specialized press and magazines, stock market analyses, financial statements, reports elaborated by governmental offices and control agencies, government strategies and programs, market reports, various web sources, as well as individual experts (including advisors, scientists and company specialists).

The transfer of knowledge between organizations is an important source of knowledge and can result in heterogenous motivation; however it is worth mentioning that a causal relationship of motivation with innovation performance and mediation of knowledge sharing was found [37]. The most important of these motivations include mimicry, as a result of which companies acquire new knowledge, mobility of human resources between organizations, as well as mutual relations between competing entities, which may foster knowledge interception in the networking process [61] (pp. 613–624). In the scientific literature, there is a theory which indicates the building of knowledge and competences of companies through boundary spanning, what is carried out as a result of the so-called boundary-crossing individuals—[62] after [63] (p. 870), [64]. This indicates that employees’ co-operation (among themselves and entities external to their mother-organization) is an important source of knowledge about the organizational environment. These employees are people who accumulate unique knowledge—e.g., through participation in conferences, membership in professional associations, and co-operation with academic communities, although their contacts may also be of a business nature and consist of the company’s suppliers, distributors and customers [65] (p. 226). Partner companies, suppliers, customers and competitors, as well as specialists and external experts, including persons representing scientific and research centers, are also among the units and entities important for acquiring new knowledge resources for the organization. In this sense, knowledge acquired from the environment allows to build key competencies of an organization and a competitive advantage by improving the organization’s operations based on acquired knowledge, better understanding the customers’ needs and determining new possibilities of satisfying them or identifying a way of reaching customers. Therefore, maintenance of relations with individuals and external entities ensures a company acquires knowledge and information about particular market, competitors and changing operating conditions, which serves to make the right management decisions [66] (p. 247).

The most important ability of a company that focuses itself on competitive knowledge-based advantages development is an accurate identification of necessary knowledge, as well as its efficient transformation and implementation [47] (p. 252). In this process, the most demanding and complicated matter is to distinguish between the layers of knowledge that are worth keeping as a company business secret and those that can be shared by building the company’s own network of co-operation around the organization [67] (pp. 109–128). Companies seeking to effectively acquire and use knowledge in their activities should systematically undertake the following actions [68] (p. 132):

- Identification of knowledge domains that are critical to the company’s operations.

- Identification of how these domains are related to each other.

- Assessment of the company’s competences and skills in these knowledge domains—i.e., its ability to integrate streams of knowledge within and across such domains.

- Assessment of the company’s competitive position in those knowledge domains—both the firm’s relative coverage of the domains as well as its relative integration skills.

- Exploration of the possible future evolution of these knowledge domains and the integration challenges that such an evolution will pose for companies operating in these domains.

- Identification of the company’s strategic options given by this evolution and the company’s current competitive position.

- Assembly and pursuit of a knowledge development strategy to create knowledge-based advantages that would deliver corporate competitiveness.

Green-technology companies in Poland have distinctive knowledge and competences, the sources of which can be found both within the organizations and in their environment. Companies acquire knowledge from specific sources in order to implement the organization’s visions and strategic objectives in the long term. This knowledge concerns the improvement of technology and production, ways of company functioning, local and international market expansion and improvement of the company’s competitive position [69] (pp. 265–274). The internal sources of knowledge in a particular company include its current and former employees of all departments, specialists and experts with diverse backgrounds who constantly co-operate with the company. The external sources provide knowledge from participants of the green technology market, government offices and institutions, associations of companies and industries, international organizations, as well as scientific and research centers and universities. These sources also include publications in scientific and industry magazines and presentations at scientific conferences and various events (e.g., trade fairs, conferences, seminars). Politicians and government officials also provide important information connected to changes in legislation, creation of environmental standards and other various findings—e.g., in the climate negotiations process.

In addition, the following types of documents can become sources of knowledge for companies:

- publicly available reports and market analyses,

- reports and analyses prepared by organizations associated in a specific profile,

- reports and analyses commissioned for a particular company,

- reports and analyses prepared by company employees,

- results of public tenders,

- financial statements and stock exchange information,

- trade publications, press releases,

- information and promotional materials for competitors.

4. Materials and Methods

The aim of the research was to identify the companies’ knowledge sources among environmental technology suppliers and list the most significant ones, as well as present core competences of companies in the new knowledge acquisition process, which allow them to successfully compete in the market and also impact the strategy and strategic goals, such as new technology development, improving technology solutions, increasing sales and market expansion.

The additional aim of the article was to find answers to the following research questions:

- What are the knowledge sources of the companies that are suppliers of green technologies in Poland?

- Which of identified knowledge sources are the most important sources of knowledge for the companies operating on the Polish market?

- What type of knowledge is acquired and developed though different knowledge sources?

- What are the competences in knowledge acquisition that the green-technology companies in Poland already present and use?

- How do green-technology companies acquire knowledge that is necessary to compete on the market?

This study was part of a larger research project entitled Green Technology Accelerator—GreenEvo (GTA GreenEvo), led by the Polish Ministry of Environment. The project was aimed at supporting the international transfer of environmentally friendly technologies and also concerned the analysis of experiences of Polish companies that are suppliers of environmental technologies in creating innovations. The specific objectives of the project included the analysis of the processes of development, promotion, sale and implementation of environmental technologies by companies that are suppliers of environmental technologies in Poland [70]. Due to the uniqueness of the project, which required the identification and analysis of a broad spectrum of topics, the research was carried out with the use of qualitative methods. The data were collected through in-depth interviews (monads, dyads and triads [71]) with companies’ representatives, and the companies they represent were the units of analysis. The semi-structured and semi-standardized in-depth interviews included over 100 detailed questions and raised a number of issues covering the following topics: introduction (7 questions), company technologies (12 questions), establishment of the company (6 questions), capital and investors (9 questions), implementations (3 questions), users (5 questions), sales process (9 questions), sources of success (6 questions), marketing (12 questions), sales (18 questions), customers (7 questions), foreign markets (8 questions), choice of markets (3 questions), relations with foreign clients (5 questions), implementation projects (10 questions), research and development (10 questions), co-operation with universities (9 questions), employees (9 questions), suppliers (2 questions), patents (17 questions), sources of innovation (4 questions), competitors (7 questions), analyzes (11 questions), certificates (4 questions), problems abroad (5 questions), public support (13 questions), and future (3 questions). The interviewees had the opportunity to interview companies’ representatives freely using an interview questionnaire. The interviews were carried out according to the logic of “one company—one interview”, although sometimes several interlocutors took part in certain interviews. The interviewees were company managers—owners, board members, and sales directors or product managers in the case of larger companies. In total, 40 interviews in 40 companies were conducted. The average duration of an interview was 157 min, but the longest was conducted for 266 min. The total duration of all interviews was 6280 min (104 h 40 min). All interviews were recorded and then transcribed. The relevant excerpts from the transcribed documents were encoded using a code book of 77 elements and analyzed using NVivo Software (version 10, QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) [72,73]. The analysis results presented in this article include information collected with the use of 15 codes specified in Table 1. The whole research was carried out in line with the grounded theory approach [74].

Table 1.

Codes established in the analysis and their descriptions. Source: the authors’ elaboration.

The empirical data used within this research project were gathered based on the experiences of the Polish companies that are suppliers of environmental technologies, laureates of three editions of the competition GTA GreenEvo. The research sample was composed of the winning companies, which were selected by a group of independent experts based on the criteria of uniqueness and quality of the technology offered by these companies, with the preliminary requirement related to their production abilities and holding Polish capital.

The selected companies also stand out from other companies in the Polish environmental technology industry because of their employment structure. They engage on average over 50 employees, whereas more than 40% of companies from the industry in Poland employ less than nine people, and around 40% employ 10 to 50 employees.

The selected companies represented six broad areas of environmental technologies: renewable energy sources, water and sewage management, waste management, biodiversity protection, energy saving and air protection. Detailed characteristics of the companies are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the researched companies. Source: the authors’ elaboration.

The researched companies are located countrywide with the predominance of the Mazovian/Mazowieckie Voivodeship (8 companies) and the Silesia/Śląskie Voivodeship (7 companies). The rest of the companies operate in the following voivodeships: Lower Silesian/Dolnośląskie (5 companies), Greater Poland/Wielkopolskie (4 companies), Małopolskie (4 companies), Kuyavian-Pomeranian/Kujawsko-Pomorskie (3 companies), Lesser Poland/Warmińsko-Mazurskie (3 companies), West Pomeranian/Zachodniopomorskie (3 companies), Lodzkie/Łódzkie (2 companies) and Pomeranian/Pomorskie (1 company).

5. Results

Customers and end-users are perceived as the most important sources of knowledge on the green technology market and environment by the interviewed companies. Significant knowledge resources coming from these entities are obtained, inter alia, by conducting analyses of customers’ needs. However, this research showed that one-third of the interviewed companies did not carry out analyses of customer needs, while in the remaining cases such analyses were carried out by the organization’s employees but obtained knowledge was not expressed in any formal documents. In most cases, in the interviewed companies, the analyses of customer needs consisted of maintaining appropriate relations (responsibilities of the sales departments employees) with customers and end-users. In all the interviewed companies, the interlocutors agreed that the knowledge connected to the expectations of customers and end-users are formed as result of the experience gained by the companies and the relations built on the basis of honesty, trust and direct contact.

“We are guided by experience, ... we have experience based on different situations. Yeah, I don’t think there’s any need for that [audience analysis—noted by transcriber/authors]. [...] I think that when there is such a consumer market, [analysis—noted by transcriber/authors] plays a huge role, but in [our] industry, the company is already smaller, here, when there is a niche shelf, I think there are different rules of the game.”[Company 10]

It was a rare practice among the researched companies to outsource the analysis of customer needs to external entities (as it might be concluded based on, e.g., the interview which the representative of Company 10 quoted above), and even if it was declared in a given company, the results of these analyses did not meet the expectations and were characterized by a very low quality. Therefore, from the perspective of the companies, it seemed more advantageous to carry out analyses of customer needs rather than task the company’s own employees from marketing and trade departments. It turns out that knowledge acquired in this way is usually not codified and does not take the form of a document. Only a few companies’ representatives admitted writing down comments and observations resulting from the analysis of customer needs.

In some of the represented green technology industries, in companies whose customers are not end-users of a particular technology, the analyses of customer needs are carried out by external organizations, including industry associations or other entities associating companies with similar profiles. Then, the necessary analyses are readily available for inspection by parties of interest—they are presented in the strategies of a given industry or government programs. In such situations, entrepreneurs rather rely on the available knowledge and resign from the maintenance of their own research.

“In fact, our company did not carry out such targeted analyses, as we know, these needs are known in advance. […]. And we make a summary of analyses that are already available on the market, [...] we use such external analyses. [...] Analyses are carried out by at least a few institutions because both the law and the [European—noted by transcriber/authors] Union requires, and this is the source of information.”[Company 37]

One of the competencies held and developed by two-thirds of companies is therefore the analysis of customer needs. This competence is shaped by companies as result of analyses carried out by individual company employees and by using generally available information contained in various publications. Therefore, in the majority of companies, analyzing the expectations of the recipients is carried out by their employees who, on the organization’s request, search for relevant information directly through the clients and recipients or use the available publications for this purpose (as, e.g., in the case of Company 37 quoted above). In rare cases, companies outsource relevant analyses to third parties.

The vast majority of companies claim that customers are an important source of organizational knowledge and are an inspiration for improving not only technological solutions but also the ways of presenting technologies and sales processes. Customers’ ideas can become an inspiration for the improvement of existing products (as representative of Company 19 stated; quoted below) or new ones’ creation, and moreover for the initiation of certain improvements in technology implementation, sales processes or complementary technologies.

“We learn a lot from our customers because they really tell us where to develop our product.”[Company 19]

A specific type of customers are institutional customers, who often have a very low level of knowledge on the technology they are acquiring and their lack of knowledge does not allow them to compare technological solutions. This type of customer usually makes purchasing decisions based on the price criterion. More than one-third of the interviewed companies are convinced that the customers do not have the knowledge that would allow them to properly evaluate technological offers. Nevertheless, some of the companies from the sample contribute to expanding customers’ knowledge through their education and training. Such actions have in some cases allowed the companies to gain a competitive advantage (e.g., Company 38 cited below).

“Customers who are beginning to take an interest in this knowledge choose our company because it is difficult to get this knowledge [that we have—noted by transcriber/authors]. This is our asset. When talking to a client, we open up to their needs, we explain as many substantive problems and solutions as possible in a way that the client can understand. This encourages cooperation with us.”[Company 38]

Competence in gaining new knowledge about customers and their needs is thus expressed by the ability of companies—green technology suppliers/providers—to conduct sales discussions with customers. Moreover, the way in which the sales competence of companies develops includes an appropriate presentation of the benefits of a particular technological solution, which is easy to understand for the customer.

Another important source of knowledge for green-technology companies are partners who enable them to gain knowledge and information connected to the market (as adaptation to local conditions mentioned by representative of Company 5 quoted below) and point out ways and means of improving the technology offered by the company and support the company in adapting its technology to specific conditions.

“[Partners contribute—noted by transcriber/authors], most often by asking us specific questions, or saying that it is standard for us to have something there, and how would you solve it. It’s always an adaptation to local conditions.”[Company 5]

Relationships with partner companies are an important way of shaping competences in the area of acquiring new knowledge. Shaped relationships enable companies to improve their competence in adapting their technological solutions to local conditions (as mentioned by representative of Company 5 quoted above), and this translates into the possibility of market expansion and increased sales.

Companies’ competition may also become an important source of knowledge. Companies may gain knowledge on their competitors by using reports prepared on behalf of the company or by purchasing reports prepared by external entities. Only a few companies have been decided by the latter-day solutions. In their opinion, overall reports mainly contain summaries of certainly known information. Three-quarters of the interviewed companies do not purchase reports, and in the opinion of one-third of them, studies on competition prepared by the company’s employees or information published in open sources are more reliable.

From the perspective of the analyzed companies, the local market in which they operate is limited, which makes their knowledge—resulting from experience, co-operation with customers and partners (including suppliers and distributors)—sufficient enough to meet their needs and carry out their own analyses. Some companies argue that it is one of the reasons why they do not outsource market reports to other entities (e.g., Company 8 quoted below).

“We know more or less the scale of the market in Poland. We know how much [certain product name—erased by transcriber/authors] is sold, how much we produce, how much share we have, and we know what is available. This market is known to us, so there is no information that we would be so interested in.”[Company 8]

This is different when it comes to gaining knowledge on international markets. Companies are willing to gain knowledge about foreign markets (e.g., Company 23) or make a declaration using various reports. Unfortunately, according to the companies represented in the sample, an important limitation is the availability of reports and budget constraints (e.g., according to representative of Company 23 quoted below), which do not allow them to hire an external company in order to prepare an appropriate report.

“I’d like to have reports on all European markets in my department. We can’t afford it. It’s too expensive.”[Company 23]

The interviewed companies gain knowledge on the competitors’ actions through the analysis of available documents about the companies and their products and participate in trade fairs that enable companies to meet their competitors and analyze the results of public procurement procedures (e.g., Company 6). In the interviewed companies, competition analyses are most often carried out on the basis of their own resources, including telephone conversations with competitors or press articles, information and advertising materials and websites.

“These offers are usually available in different places: at different trade fairs, on the Internet. If we have something we want to confront, we ask ourselves a question about an offer for something.”[Company 6]

Customers and partners are treated also as an important source of knowledge about companies’ competition, who are in possession of information connected to competitors’ technologies and activities. As in the case of customer analyses, a competition analysis and its results are not formalized documents (as, e.g., the representative of Company 38 mentioned).

“Formalized analysis is not done. Rather, based on analyses of what the company is doing. It’s not formalized knowledge, on paper, it’s my knowledge. I know who does what, where. It’s a narrow industry.”[Company 38]

To sum up, competencies in the field of competition and market analysis are shaped by companies with the use of analyses developed by their employees. When developing this competence, relations with both customers and partners are important. Competence in the field of international market analysis is less frequently demonstrated by enterprises of green technology suppliers in Poland. The lack of this type of competence makes these companies more likely to use analyses developed by external entities.

An important source of knowledge from the point of view of green-technology companies are European and domestic laws and draft legislations. In total, 35 companies in interviews stated that they monitor changes in legislation and follow the work on emerging legislation, both on a domestic/internal and European level. Some of them also follow the course of climate negotiations, changes in European Union regulations or even co-operate in consulting on laws concerning the companies’ operation area (as, e.g., in the case of Company 20, which representative is quoted below).

“Of course, [that we follow the changes in the law—noted by transcriber/authors]. We consult them as a member of [name of industry organization—erased by transcriber/authors]. So, we know what’s being passed, what’s new, what the dangers....”[Company 20]

In some of the interviewed companies, monitoring changes in legal regulations is the responsibility of the legal department, which operates in a small number of the interviewed companies. In a significant part of the interviewed companies, legal offices are hired (as, e.g., in the case of Company 6) in order to monitor changes in legal regulations that are important for these companies.

“We have a law firm that informs us what we need to know about this matter [about changes in the law and new legislative initiatives—noted by transcriber/authors].”[Company 6]

Competence in the analysis of legal regulations and changes is delegated to institutions co-operating with companies—e.g., law firms and law offices. Environmental technology providers in Poland are not able to identify, analyze and apply regulations related to the specificity of their business.

The interviewed companies declare that they participate in seminars and industry conferences. More than a quarter of them claim that they participate in specialized conferences on narrow issues, most often as speakers, but they are not a source of new knowledge for the company (according to comment of Company 38′s representative quoted below).

“There are no such [seminars and conferences—noted by transcriber/authors] in Poland. I’ve been to a few, but rather not to gain new knowledge.”[Company 38]

Moreover, only individual persons representing green-technology companies declared that their companies observe the development of scientific research in areas close to the company’s activity or mentioned co-operation with scientific and research centers and universities (according to declarations of Company 6′s representative quoted below).

“We keep track of the state of the art in our industry [...], mainly through the Internet, publications and cooperation with institutes, where we exchange what is happening in the world.”[Company 6]

An important problem for the interviewees was to distinguish between scientific articles presenting research results and publications in trade journals, popular and scientific literature or content already available on web portals. Unfortunately, many of the interviewees confused industry reports with scientific research results, which are most often presented in scientific journals. This is undoubtedly a limitation of these companies’ research that they carried out.

Another way of gaining knowledge by the interviewed green-technology companies are maintenance relations with journalists who publish, for example, in the trade press and industry web portals. More than three-quarters of companies declared that they subscribe and read trade journals (as, e.g., representative of Company 32 declared (quoted below)), contrary to scientific journals.

“[We read—noted by transcriber/authors] trade magazines about the market in which our clients operate [...]. Even the Spanish journals that come to us.”[Company 32]

Companies gain new knowledge and shape their competences to achieve strategic goals by participating in conferences and industry seminars, reading trade publications and partly by following the development of science and research in the area of their interest.

To sum up the research outcomes described above, the summary of the most important results is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of the most important research results. Source: Own elaboration.

6. Discussion

In this paper the authors took into consideration resource-based theory and knowledge management (which are complementary—the knowledge-based view of a company is an extension of the resource-based view [45]) as thus refer to these frameworks—e.g., [1,3]. Identification of sources related to knowledge, competences and competitive advantages acquisition and management was listed among the main premises of this article. These premises were considered in the context of deliberation on Polish green-technology companies’ success.

As it was mentioned in Section 2 of this paper, representatives of resource-based theory were focused on identification and explanation—which of the resources are stated as important to a particular company and treated as crucial when gaining a competitive advantage in the particular market. The collected qualitative data enabled the identification of the most important sources of knowledge in green-technology companies in Poland, which constituted the basis of their key competences and thus enabled them to build a competitive advantage. Moreover, the sources of knowledge distinguished by the interviewed companies refer to the relations created by the analyzed companies with market participants and other entities and the knowledge about the market and its participants gained through these relations and other available information. The analysis of the collected data and the obtained results allowed to create a descriptive model for the acquisition of new knowledge by green-technology companies in Poland, which serves as a basis for gaining distinctive competences by these companies. Core competencies [54] and dynamic capabilities [44] arising from the various identified knowledge sources enabled companies to access various markets (also outside Poland) and helped them to grow and develop their portfolios. Based on the presented research, it can be stated that green-technology companies in Poland are consciousness of their knowledge and treat it as an important asset of their competitive advantage.

In order to summarize the results of this qualitative empirical research, it can be concluded that, currently, the organizations’ employees are most often responsible for gaining new knowledge (especially those employees, who co-operate directly with other market participants—e.g., partners, suppliers, distributors, customers and end-users). These daily business contacts become a source of knowledge about the organization’s environment, including, i.e., the competition and the needs of current and future customers and recipients. In this way, the gained knowledge leads to the improvement of a particular company’s current technology and product offerings and is used in order to improve implementations, organize the sales process, and create products and services complementary to the offered technology. Foreign partners who support companies in modifying and adapting their technology to the expectations of foreign customers and recipients are also an important source of knowledge related to the development of green-technology companies, especially when it comes to their international expansion. Competence in gaining new knowledge on customers (and other stakeholders) and their needs is therefore core to the development of green-technology companies. Such knowledge becomes an asset of companies, which are conscious of inputs, outputs and moderating factors of the knowledge-creating process, and unique resources within themselves [4].

Numerous interviewed companies used readily available, inexpensive, or even free-of-charge industry publications—e.g., industry magazines, web portals and reports provided by industry associations. The financial issue was important for reports on foreign markets, where companies declared their willingness to purchase a report; however, they decided not to take advantage of this opportunity due to the high costs of such a service and their own budget constraints. Polish green-technology companies, instead of using already available reports on markets, monitor the market with their own expenditure, primarily preparing their own analyses of customer needs—gathering knowledge about what the competition offers—based on information from trade fairs and materials (e.g., on the website or in the trade press) made available by competitors, and the results of public procurement procedures. However, these companies rarely documented their observations, remarks, and reflections in permanent forms of corporate notes and documents. Thus, the use of this knowledge depends widely on the competences of a company’s employees who gathered relevant information.

As far as the knowledge and competences of a company’s employees regarding strategic resources are concerned, companies gain new knowledge and shape their competences to achieve strategic goals by use of analyses developed by their employees, by relations with both customers and partners, by customers’ opinions, by participating in conferences and industry seminars, by reading trade publications and partly by following the development of their scientific and research abilities in the area of their interest.

The companies also try to monitor the relevant legislation on their own, the course of climate negotiations and the creation of new ecological standards. Some companies are involved in consulting on new legal projects. Knowledge concerning changes in the law is acquired by the employees of legal departments of the largest interviewed companies, while the remaining companies benefit from the support of legal service offices and law firms.

Therefore, the interviewed companies develop competence in the area of acquiring new knowledge concerning their competitors, clients and recipients, markets and possible changes within markets, using the identified sources of knowledge.

The ability to use particular sources of knowledge enables companies to create new products, services and technological solutions, as well as enter new markets and increase sales. In general, these translate/transpose into the products, services and technological solutions offered, with the possibility of their improvement and adaptation to local conditions, and thus into their position in the market and their competitive advantage. Therefore, most of the competences in the area of knowledge acquisition are formed within enterprises, while very few require co-operation with external entities,—e.g., law firms and law offices. However, there is still some potential for exploitation of other opportunities and making companies aware that they can expand their package of key knowledge acquisition opportunities to increase their skill and competences.

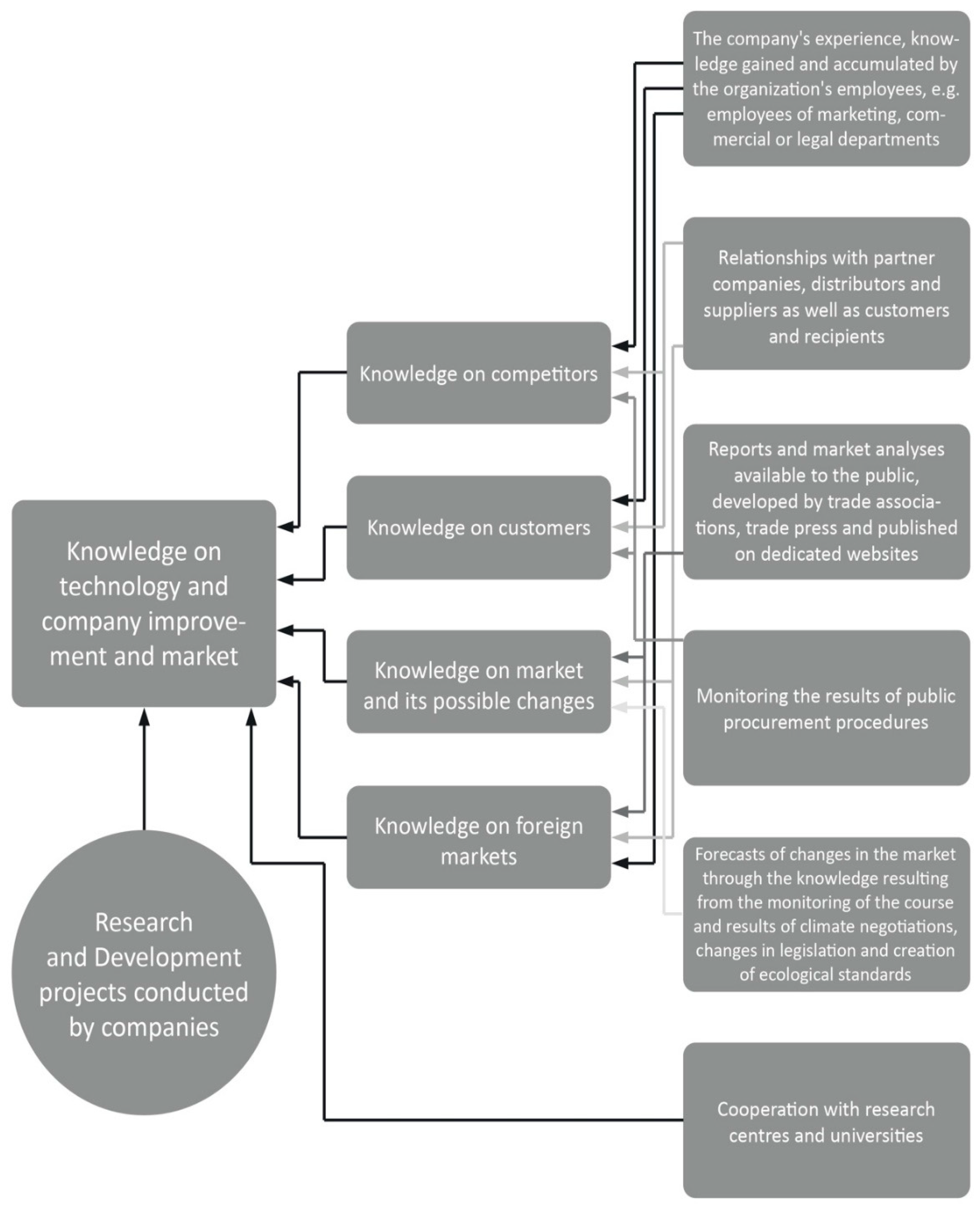

The results of the conducted research are summarized in Figure 1, which presents a model of acquiring new knowledge by green-technology companies in Poland, which serves as a basis for gaining distinctive competences by these companies.

Figure 1.

A model of acquiring new knowledge by green-technology companies in Poland. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Although this paper discusses the Polish market only, it may be mentioned that, e.g., a green entrepreneurial orientation had positive influences on both the environmental and financial performance of companies, which is one of China’s research results [6]. The content-based analysis of publications describing the operations of green-technology companies on other markets shows that such contributions are rather rare and are available only for some countries,—e.g., for China [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14], Australia [15], Brazil [16], Canada [17], Finland [18], Germany [19,20], India [21,22], Japan [23], Malaysia [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], Pakistan [32,33,34,35,36,37], Romania [38], Slovakia [39], the Asian-Pacific area (including Taiwan, South Korea, China, Hong Kong, India) [40] and European countries (including France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom as one group) [41]. However, these contributions do not focus specifically on knowledge, competences and the competitive advantage of the green-technology companies. Thus, this research on the sample of Polish companies contributes to fill this research gap.

Nevertheless, a large group of countries is not analyzed in this context, even briefly. This conclusion is based on the analysis of publications collected in the Scopus and the Web of Science databases. In the Scopus database, 87 publications were obtained in total, and 34 in the Web of Science, in most cases the same. Each of the publications’ contents have been reviewed in terms green-technology companies and only those that have been flagged are consistent with the topic analyzed in the article. The numbers are small, and no analyses has been carried out for most of the countries. This is the basis for future research—namely, to analyze companies in countries not included in the above-mentioned list. This will be the subject of further research by the authors of this article or may inspire other researchers.

7. Conclusions

The presented research focused on the identification of knowledge and competence sources in Polish green-technology companies, with particular interest in competitive advantage. The ways of gaining and developing identified knowledge and competences were analyzed and the importance of identified knowledge and competences was assessed. Consequently, this paper resulted in the development of the model of acquiring new knowledge by green-technology companies in Poland. This model serves as a basis for gaining distinctive competences by these companies.

The contents of this paper include: the identification of knowledge and competence sources in Polish green-technology companies, a description of the ways of gaining and developing identified knowledge and competences, as well as an assessment of the importance of identified knowledge and competences. These are, on the one hand, practical implications since the present actions or decisions of the analyzed companies that have an impact on green technologies’ development and might be useful for both business organizations and wider audiences. On the other hand, these can be seen as scientific implications as well, since they add to the knowledge base related to sustainability and technology development by listing specific sources of knowledge and competences along with their importance.

The limitations of this study mainly regard methodological aspects. The interviewees were companies’ managers: owners, board members, and sales directors or product managers in the case of larger companies; therefore, customers’ opinions were not collected. Moreover, the researched companies were located countrywide (Poland) with a certain geographical predominance. Finally, analyzed companies represent the most innovative environmental technology suppliers in Poland; thus, activities they perform may not be easily transformed, translated or used by other, less innovative entities in the sector.

The research results allow the identification of future research directions. As it was mentioned at the end of the previous section, one of the potential future studies could conduct similar analyses of companies in countries not listed in a content-based analysis of publications describing operations of green-technology companies. Another idea for future research would be to compare inputs and outputs connected to green-technology companies worldwide. Equity crowdfunding for green technologies development, as the concept for future research, is worth considering as well. The idea of research on the effects of intellectual capital and knowledge sharing impact on the success rate of campaigns of equity crowdfunding for green technology development was inspired by [75]. These topics present promising possibilities for future developments of the described analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.; formal analysis, M.M. and A.J.; funding acquisition, M.M. and A.J.; methodology, M.M. and A.J.; writing—original draft, M.M., A.J. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.M. and M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was partially funded by the Faculty of Management, University of Warsaw. The article presents i.a. selected results of the research grant awarded to Magdalena Marczewska by the National Science Center (DEC-2014/12/T/HS4/00311).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, X.; Ding, Y.; Li, Y. M-Government Cooperation for Sustainable Development in China: A Transaction Cost and Resource-Based View. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, M.; Papaluca, O.; Sasso, P. The System Thinking Perspective in the Open-Innovation Research: A Systematic Review. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2018, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conchado Peiró, A.; Carot Sierra, J.M.; Vázquez Barrachina, E. Competences of Flexible Professionals: Validation of an Invariant Instrument across Mexico, Chile, Uruguay, and Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Toyama, R.; Konno, N. SECI, Ba and leadership: A unified model of dynamic knowledge creation. Long Range Plann. 2000, 33, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezi, L.; Ferraris, A.; Papa, A.; Vrontis, D. The Role of External Embeddedness and Knowledge Management as Antecedents of Ambidexterity and Performances in Italian SMEs. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Chai, H.; Shao, J.; Feng, T. Green entrepreneurial orientation for enhancing firm performance: A dynamic capability perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 1311–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xing, C.; Wang, Y. Does green innovation mitigate financing constraints? Evidence from China’s private enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, L.; Yang, Q. Do corporate environmental ethics influence firms’ green practice? The mediating role of green innovation and the moderating role of personal ties. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 266, 122054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Qian, Q.; Jiao, J.; Li, L.; Li, F.; Yang, R. Can environmental innovation benefit from outward foreign direct investment to developed countries? Evidence from Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 13790–13808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Xie, M. Can direct environmental regulation promote green technology innovation in heavily polluting industries? Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 746, 140810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Cao, C. Impact of quality management on green innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Long, H. Research Focus, Frontier and Knowledge Base of Green Technology in China: Metrological Research Based on Mapping Knowledge Domains. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2020, 29, 3003–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Liang, S. Study on the efficiency and regional disparity of green technology innovation in China’s industrial companies. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2016, 14, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, W.; Feng, Y.; Xu, P. “Turning green into gold”: A framework for energy performance contracting (EPC) in China’s real estate industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 109, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, M.; Lloyd, M. Claiming the green revolution—protecting investment in green mineral processing. In Proceedings of the XXV International Mineral Processing Congress 2010 (IMPC 2010), Brisbane, Australia, 6–10 September 2010; Curran: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 5, pp. 3555–3562. [Google Scholar]

- Menezes, C.C.N.; dos Santos, S.M.; de Bortoli, R. Environmental technology mapping: A study on green patents in Brazil. Rev. Gest. Ambient. Sustentabilidade-GEAS 2016, 5, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, T.; Tomszak, J.; Lawrence, S.; Richardson, L.; Hepburn, K. Environmentally friendly fracturing fluid as utilized in a western Canada sedimentary basin case study. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 27–29 October 2014; Curran: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 3, pp. 2157–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunila, M.; Rantala, T.; Ukko, J.; Havukainen, J.; Saunila, M. Why invest in green technologies? Sustainability engagement among small businesses. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2019, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakura, S. Open innovation as a driver for new organisations: A qualitative analysis of green-tech start-ups. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2020, 12, 109–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J. Germany: Managing the downswing. Photonics Spectra 2010, 44. Available online: https://www.photonics.com/Articles/Germany_Managing_the_downswing/p2/vo79/i490/a41327 (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Gupta, R.; Agrawal, G. Corporate social responsibility in emerging economies: Assessing environmental reporting of Indian firms. Int. Bus. Manag. 2016, 10, 1575–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Sharma, M. Impact of green production and green technology on sustainability: Cases on companies in India. Int. J. Mech. Prod. Eng. Res. Dev. 2017, 7, 591–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, T.; Goto, M. DEA Non-Radial Approach for Resource Allocation and Energy Usage to Enhance Corporate Sustainability in Japanese Manufacturing Industries. Energies 2019, 12, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Lin, C.; Ahmad, M.; Omar, N.A.; Ali, M.H. Factors Affecting Energy-Efficient Household Products Buying Intention: Empirical Study. Environ. Clim. Technol. 2019, 23, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, Y.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Wah, W.-X. Pursuing green growth in technology firms through the connections between environmental innovation and sustainable business performance: Does service capability matter? Resourc. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, Y.; Wah, W.X. Eco-innovation practices: Insight from Malaysia’s green technology sector. In Business Transformation and Sustainability through Cloud System Implementation; Soliman, F., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2014; pp. 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, Y.; Wah, W.X. The impact of eco-innovation drivers on environmental performance: Empirical results from the green technology sector in Malaysia. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2017, 12, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, Y.; Wah, W.X.; Shaharudin, M.S. Does a firm’s innovation category matter in practising eco-innovation? Evidence from the lens of Malaysia companies practicing green technology. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2016, 27, 208–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, M.F.M.; Shuqi, A.L. The effects of environmental management system towards company financial performance in Southern Region of Peninsular Malaysia. J. Environ. Treat. Technol. 2019, 7, 794–801. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, H.; Mansor, N.A.; Krubally, M.; Balder, N.; Ullah, H. Investigating the impact of dynamic and relational learning capabilities on green innovation performance of SMEs. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2019, 6, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zailani, S.; Iranmanesh, M.; Nikbin, D.; Binti Jumadi, H. Determinants and environmental outcome of green technology innovation adoption in the transportation industry in Malaysia. Asian J. Technol. Innov. 2014, 22, 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Javed, S.A.; Zafar, A.U.; Rehman, S.U. Relation of environment sustainability to CSR and green innovation: A case of Pakistani manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Sağsan, M. Impact of knowledge management practices on green innovation and corporate sustainable development: A structural analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunnan, L.; Jamil, K.; Abrar, U.; Arain, B.; Guangyu, Q.; Awan, F.H. Analyzing the Green Technology Market Focus on Environmental Performance in Pakistan. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Computing, Mathematics and Engineering Technologies (iCoMET), Sukkur, Pakistan, 29–30 January 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, T. Impact of Quality Management on Green Innovation: A Case of Pakistani Manufacturing Companies. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Smart Innovation, Ergonomics and Applied Human Factors (SEAHF), Madrid, Spain, 22–24 January 2019; Benavente-Peces, C., Slama, S., Zafar, B., Eds.; SEAHF 2019. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 150, pp. 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuhui, Y.; Yu, Z.; Rehman Khan, S.A.; Abbas, H. Effect of Green Practices on Organizational Performance: An Evidence from Pakistan. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Syst. 2020, 19, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, S.H.; Zakariya, R.; Vrontis, D.; Santoro, G.; Christofi, M. High-performance work systems, innovation and knowledge sharing: An empirical analysis in the context of project-based organizations. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robescu, V.O. Eco Innovation Practice and Romanian SMEs. In Proceedings of the 5th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Athens, Greece, 16–17 September 2010; Kakouris, A., Ed.; Academic Publishing Limited: Reading, UK, 2010; pp. 480–488. [Google Scholar]

- Marsina, S.; Hamranova, A.; Hrivikova, T.; Bolek, V.; Zagorsek, B. How can project orientation contribute to pro-environmental behavior in private organizations in Slovakia. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.J.M. Roadmap of green-oriented technology in PCB industry within Asia-pacific. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Environmentally Conscious Design and Inverse Manufacturing (Eco Design 2005), Tokyo, Japan, 12–14 December 2005; Yamamoto, R., Furukawa, Y., Hoshibu, H., Eagan, P., Griese, H., Umeda, Y., Aoyama, K., Eds.; IEEE Computer SOC: Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombelli, A.; Ghisetti, C.; Quatraro, F. Green technologies and firms’ market value: A micro-econometric analysis of European firms. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2020, 29, 855–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, G.; Prahalad, C.K. Competing for the Future; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, J.; Tidd, J.; Arasti, M.R. Dynamic capability and diversification. In From Knowledge Management to Strategic Competence. Assessing Technological, Market and Organisational Innovation; Tidd, J., Ed.; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2012; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Curado, N.; Bontis, N. The knowledge-based view of the firm and its theoretical precursor. Int. J. Learn. Intellect. Cap. 2006, 3, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galikhanov, M.F.; Ilyasova, A.; Ivanov, V.; Gorodetskaya, I.M.; Shageeva, F.T. Continuous professional education as an instrument for development of industry employees’ innovational competences within regional territorial-production cluster. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning, Florence, Italy, 20–24 September 2015; pp. 251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Thrassou, A.; Vrontis, D.; Crescimanno, M.; Giacomarra, M.; Galati, A. The requisite match between internal resources and network ties to cope with knowledge scarcity. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 861–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryszko, A. Interorganizational cooperation, knowledge sharing, and technological eco-innovation: The role of proactive environmental strategy—empirical evidence from Poland. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2016, 25, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallucci, T.; Dimitrova, V.; Marinov, G. Interrelation between Eco-Innovation and Intra-Industry Trade—A Proposal for a Proxy Indicator of Sustainability in the EU Countries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennings, K. Redefining innovation—eco-innovation research and the contribution from ecological economics. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockett, A.; Thompson, S.; Morgenstern, U. The development of the resource-based view of the firm: A critical appraisal. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2009, 11, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P. Environmental technologies and competitive advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 1995, 16, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hamel, G. The core competence of the corporation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1990, 68, 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprises performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katkalo, V.S.; Pitelis, C.N.; Teece, D.J. Introduction: On the nature and scope of dynamic capabilities. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2010, 19, 1175–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R. Towards a knowledge based theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, R. Knowledge Management Systems. Information and Communication Technologies for Knowledge Management, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 1–630. [Google Scholar]

- Nagano, H. The growth of knowledge through the resource-based view. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, G. Knowledge transfer in vertical relationship: The case study of Val d’Agri oil district. J. Knowl. Manag. 2013, 17, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushman, M.L.; Scanlan, T.J. Boundary Spanning Individuals: Their Role in Information Transfer and Their Antecedents. Acad. Manag. J. 1981, 24, 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Klincewicz, K. Cele zarządzania wiedzą. In Zarządzanie Wiedzą. Podręcznik Akademicki; Jemielniak, D., Koźmiński, A.K., Eds.; Wydawnictwa Akademickie i Profesjonalne: Warsaw, Poland, 2008; pp. 71–104. [Google Scholar]

- Beechler, S.; Sondergaard, M.; Miller, E.; Bird, A. Boundary Spanning. In The Handbook of Global Management: A Guide to Managing Complexity; Lane, H., Maznevski, M., Mendenhall, M., McNett, J., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Klincewicz, K. Systemy i struktury gromadzenia i rozpowszechniania wiedzy. In Zarządzanie Wiedzą. Podręcznik Akademicki; Jemielniak, D., Koźmiński, A.K., Eds.; Wydawnictwa Akademickie i Profesjonalne: Warsaw, Poland, 2008; pp. 176–219. [Google Scholar]

- Latusek, D. Pozyskiwanie wiedzy z otoczenia. Wywiad gospodarczy. Relacje z partnerami oparte na wiedzy. In Zarządzanie Wiedzą. Podręcznik Akademicki; Jemielniak, D., Koźmiński, A.K., Eds.; Wydawnictwa Akademickie i Profesjonalne: Warsaw, Poland, 2008; pp. 220–245. [Google Scholar]

- Boisot, M. The creation and sharing knowledge. In Knowledge, Organization and Management. Building on the Work of Max Boisot; Child, J., Ihrig, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: UK, Oxford, 2013; pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ihrig, M.; MacMillan, I. The strategic management of knowledge. In Knowledge, Organization and Management. Building on the Work of Max Boisot; Child, J., Ihrig, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Jednoralska, A. Wizje Przyszłości Dostawców Technologii Środowiskowych. In Polski Rynek Technologii Środowiskowych—Doświadczenia Dostawców, Rekomendacje dla Instytucji Publicznych. Raport z Badań; Klincewicz, K., Ed.; Polish Ministry of Environment: Warsaw, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Klincewicz, K. The Market for Environmental Technologies in Poland—Experiences of Technology Providers, Lessons Learned for Public Institutions. Synthesis Report; Ministry of Environment: Warsaw, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Mitchell, M. In-depth interviews. In Collecting Qualitative Data; Guest, G., Namey, E., Mitchell, M., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: London, UK, 2013; pp. 113–171. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, R.S.; Koerber, A.L. Using NVivo to Answer the Challenges of Qualitative Research in Professional Communication: Benefits and Best Practices Tutorial. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 2011, 54, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, A.; Myers, R.; Kowler, L.; Tovar, J.G. Project Guide to Coding in Nvivo and Codebook. Guideline; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2015; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, K. Grounded Theory in Management Research; SAGE Publications: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vrontis, D.; Christofi, M.; Battisti, E.; Graziano, E.A. Intellectual capital, knowledge sharing and equity crowdfunding. J. Intellect. Cap. 2020. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).