Corporate Social Responsibility Influencing Sustainability within the Fashion Industry. A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Corporate Social Responsibility

2.2. Sustainable Development and Sustainability

2.3. The Connection between CSR and Sustainability

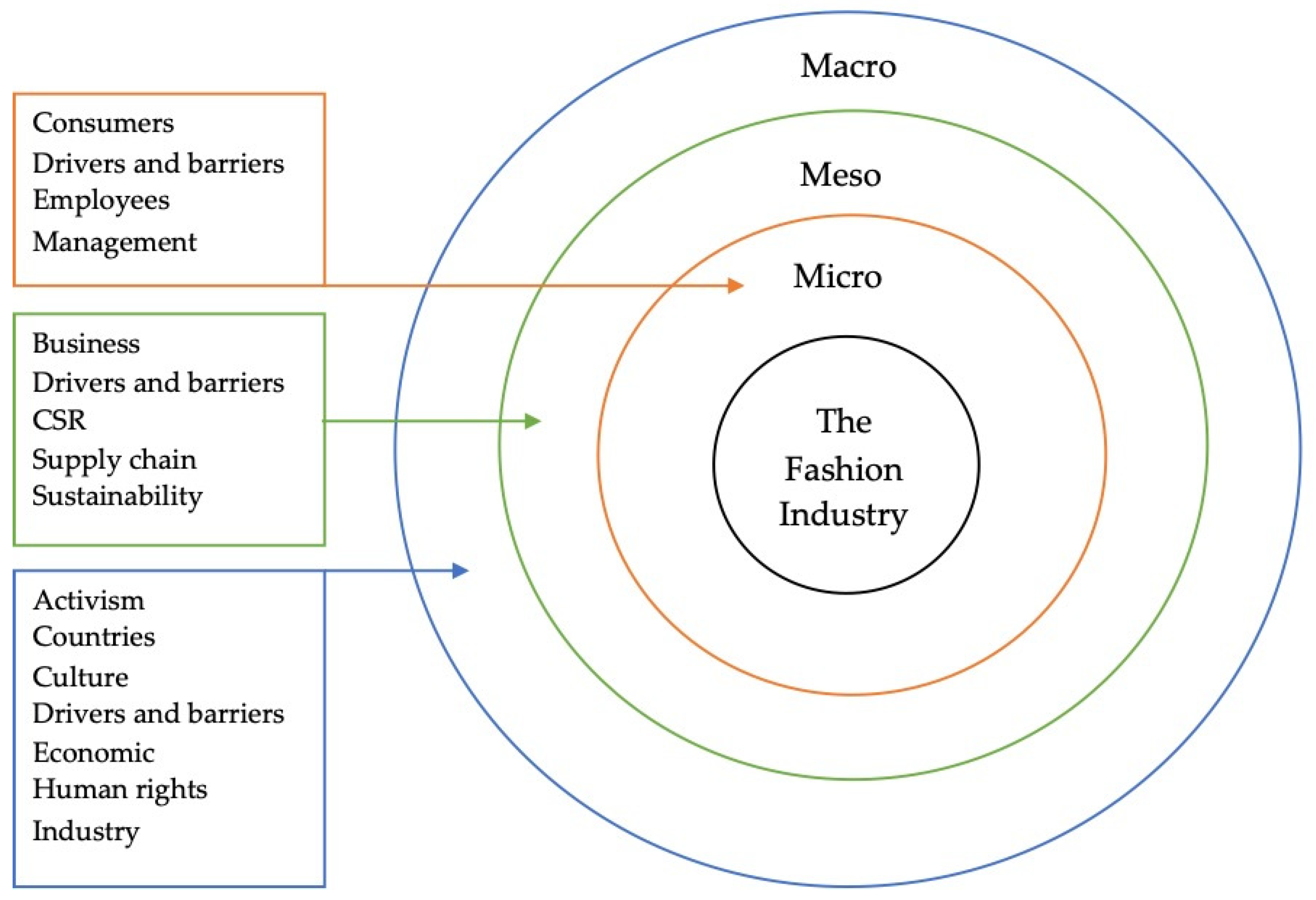

2.4. The Micro-Meso-Macro Framework

2.5. Sustainable Fashion

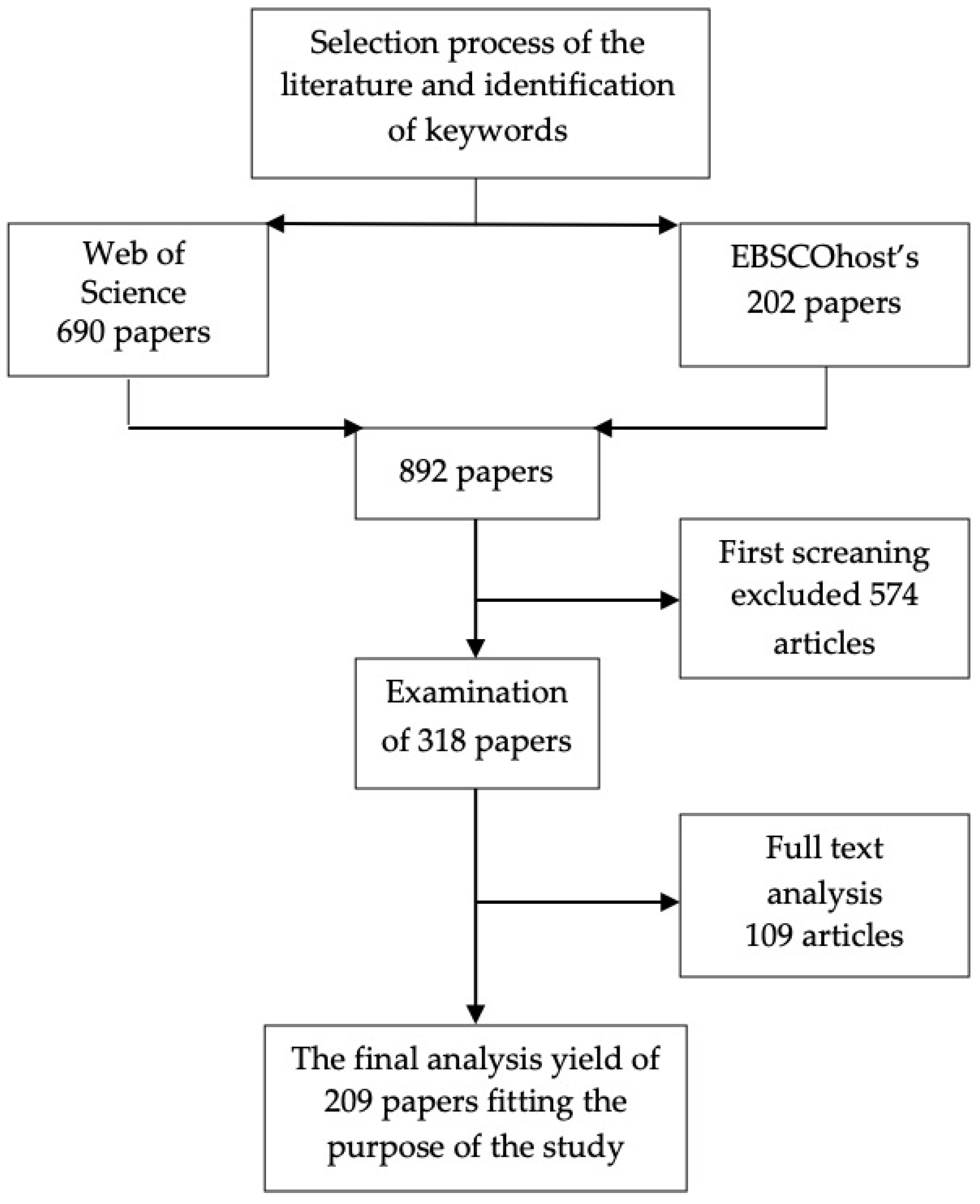

3. Methods

3.1. Planning Review

3.2. Conducting the Review

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.4. Reporting and Dissemination

4. Findings

4.1. Years and Journal of Publication

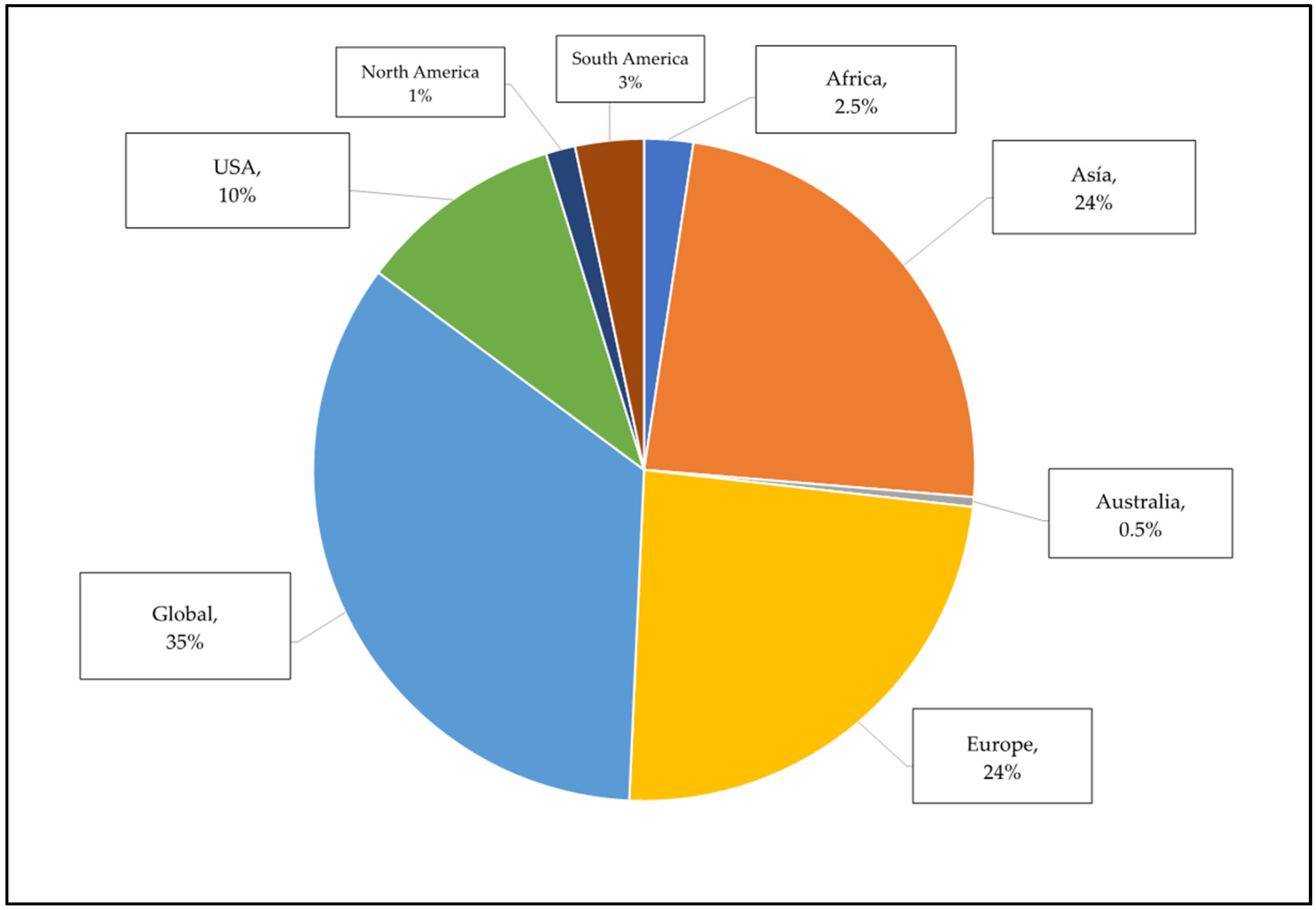

4.2. Research Focus by Regions

4.3. Studies by a Theoretical Approach

4.4. Overview of Studies by Aim, Purpose, and Objective

4.5. Overviews of Keywords by Industry and Frequency of Keywords

4.6. Analysis of Studies by Key Concepts

4.7. Key Topics and Related Sub-Topics

4.8. Corporate Social Responsibility

4.9. Sustainability

4.10. Contribution and Suggestion for Future Research

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author (Year) | Title | Journal | Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adam (2018) | The Role of Human Resource Management (HRM) for the Implementation of Sustainable Product-Service Systems (PSS)—An Analysis of Fashion Retailers | Sustainability | Product-service systems (PSS); Human resource management (HRM); Fashion industry; Sustainable business models; Sustainable retail |

| Ahlstrom (2010) | Corporate Response to CSO Criticism: Decoupling the Corporate Responsibility Discourse from Business Practice | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | Corporate responsibility; discourse theory; New institutional theory; Civil society organizations (CSOs); Outsourced production; Garment industry; Code of conduct; Profit maximization |

| Albloushy et al. 2019) | Purchasing environmentally sustainable apparel: The attitudes and intentions of female Kuwaiti consumers | International Journal of Consumer Studies | Environmental concern; Environmental knowledge; Environmentally sustainable Apparel; purchasing behaviors; Kuwait |

| Anner (2017) | Monitoring Workers’ Rights: The Limits of Voluntary Social Compliance Initiatives in Labor Repressive Regimes | Global Policy | None |

| Anner (2018) | CSR Participation Committees, Wildcat Strikes and the Sourcing Squeeze in Global Supply Chains | British Journal of Industrial Relations | None |

| Aquino (2011) | The Performance of Italian Clothing Firms for Shareholders, Workers and Public Administrations: An Econometric Analysis | Journal of Accounting Research & Audit Practices | None |

| Arrigo (2018) | The flagship stores as sustainability communication channels for luxury fashion retailers | Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services | Flagship store; Sustainable retailing; Luxury fashion brands; Luxury sustainability; In-store communication |

| Athukorala et al. (2018) | Repositioning in the global apparel value chain in the post-MFA era: Strategic issues and evidence from Sri Lanka | Development Policy Review | Apparel industry; Global value chain; Multi-Fiber Arrangement; Sri Lanka |

| Austgulen (2016) | Environmentally Sustainable Textile Consumption-What Characterizes the Political Textile Consumers? | Journal of Consumer Policy | Sustainable consumption; Political consumption; Textiles; Clothing; Environmental regulation; Consumerism |

| Bair et al. (2012) | From Varieties of Capitalism to Varieties of Activism: The Antisweat shop Movement in Comparative Perspective | Social Problems | Anti-sweatshop movement; Global commodity chains; Transnational advocacy networks; Varieties of capitalism; Labor rights |

| Bartley (2003) | Certifying forests and factories: States, social movements, and the rise of private regulation in the apparel and forest products fields | Politics & Society | Private regulation; Certification; Sweatshops; Deforestation; Corporate Social Responsibility |

| Bartley et al. (2015) | Responsibility and neglect in global production networks: the uneven significance of codes of conduct in Indonesian factories | Global Networks a Journal of Transnational Affairs | Global production networks; Global value chains; Social movements; Labor standards; Code of conduct; Apparel; Electronics; Indonesia |

| Bartley et al. (2016) | Beyond decoupling: unions and the leveraging of corporate social responsibility in Indonesia | Socio-Economic Review | Corporate social responsibility; Globalization; Trade unions; Developing countries; Institutional theory |

| Baskaran et al. (2012) | Indian textile suppliers’ sustainability evaluation using the grey approach | International Journal of Production Economics | Grey approach; India; Supplier evaluation; Sustainability; Textile industry |

| Battaglia et al. (2014) | Corporate Social Responsibility and Competitiveness within SMEs of the Fashion Industry: Evidence from Italy and France | Sustainability | Competitiveness; Corporate social responsibility; Fashion industry; SMEs; Textile |

| Battistoni et al. (2019) | Systemic Incubator for Local Eco entrepreneurship to Favor a Sustainable Local Development: Guidelines Definition | Design Journal | Systemic design; Eco-entrepreneurship; Local economic; Development; Zero waste; Business incubator; Textile; Piedmont Region |

| Benjamin et al. (2014) | An Exploratory Study to Determine Archetypes in the Trinidad and Tobago Fashion Industry Environment | West Indian Journal of Engineering | Diversification; Operant Subjectivity; Fashion industry; Q-Study |

| Bjorquist et al. (2018) | Textile qualities of regenerated cellulose fibers from cotton waste pulp | Textile Research Journal | Cotton waste pulp; Staple fiber; Circular economy; Environmental sustainability; Spinning; Fabrication |

| Borjeson et al. (2015) | Knowledge challenges for responsible supply chain management of chemicals in textiles as experienced by procuring organizations | Journal of Cleaner Production | Responsible procurement; Knowledge; Corporate social responsibility; Chemical risks |

| Brennan et al. (2014) | Rhetoric and argument in social and environmental reporting: The Dirty Laundry case | Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal | Environmental reporting; Stakeholder; Rhetoric; Argument; Greenpeace |

| Briga-Sa et al. (2013) | Textile waste as an alternative thermal insulation building material solution | Construction and Building Materials | Textile waste; Thermal conductivity; Eco-efficient; Building solution; Sustainability |

| Burzynska et al. (2018) | Opportunities and Conditions for the Development of Green Entrepreneurship in the Polish Textile Sector | Fibers & Textiles in Eastern Europe | Textile industry; Green entrepreneurship; Innovations; European Union |

| Busi et al. (2016) | Environmental sustainability evaluation of innovative self-cleaning textiles | Journal of Cleaner Production | Life Cycle Assessment; Self-cleaning textiles; Nanotechnology; Environmental sustainability |

| Caniato et al. (2012) | Environmental sustainability in fashion supply chains: An exploratory case-based research | International Journal of Production Economics | Environmental sustainability; Supply chain management; Fashion industry; Case studies |

| Carrigan et al. (2013) | From conspicuous to considered fashion: A harm-chain approach to the responsibilities of luxury-fashion businesses | Journal of Marketing Management | Harm chain; Value co-creation; Institutional theory; Luxury fashion; Corporate Social Responsibility |

| Chang et al. (2015) | Is fast fashion sustainable? The effect of positioning strategies on consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions | Social Responsibility Journal | Sustainability; Consumer behavior; Fast fashion; Positioning strategies |

| Chen et al. (2014) | Implementing a collective code of conduct-CSC9000T in Chinese textile industry | Journal of Cleaner Production | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR); ISO 26000; China; Textile |

| Chen et al. (2017) | Decent Work in the Chinese Apparel Industry: Comparative Analysis of Blue-Collar and White-Collar Garment Workers | Sustainability | Decent work; Garment Manufacturing; Blue-collar workers; White-collar workers; China |

| Cho et al. (2015) | Style consumption: its drivers and role in sustainable apparel consumption | International Journal of Consumer Studies | Consumer ethics; Guilt; Shame; Australia; Indonesia |

| Choi (2013) | Local sourcing and fashion quick response system: The impacts of carbon footprint tax | Transportation Research Part E-Logistics and Transportation Review | Sustainability; Local sourcing; Quick response system; Carbon footprint tax; Sustainability |

| Choi et al. (2018) | Used intimate apparel collection programs: A game-theoretic analytical study | Transportation Research Part E-Logistics and Transportation Review | Supply chain management; Used intimate apparel collection program; Reverse logistics; Socially responsible operations |

| Clarke-Sather et al. (2019) | Onshoring fashion: Worker sustainability impacts of global and local apparel production | Journal of Cleaner Production | Sustainable sourcing; Life cycle assessment; Apparel product development; Sustainability assessment; Apparel industry |

| Connell et al. (2012) | Sustainability knowledge and behaviors of apparel and textile undergraduates | International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education | United States of America; Undergraduates; Clothing; Consumer behavior; Sustainability; Apparel purchasing behavior; Apparel sustainability; Sustainability knowledge |

| Cooke et al. (2010) | Corporate social responsibility and HRM in China: a study of textile and apparel enterprises | Asia Pacific Business Review | Business ethics; China; CSR; HRM; Private enterprises |

| Cortes et al. (2017) | A Triple Bottom Line Approach for Measuring Supply Chains Sustainability Using Data Envelopment Analysis | European Journal of Sustainable Development | Data Envelopment Analysis; Sustainability; Supply Chains; Triple Bottom Line; Fast Fashion |

| Cowan et al. (2014) | Green spirit: consumer empathies for green apparel | International Journal of Consumer Studies | Apparel; Eco; Environmentally friendly; Green; Sustainability; Theory of planned behavior |

| Crinis et al. (2010) | Sweat or No Sweat: Foreign Workers in the Garment Industry in Malaysia | Journal of Contemporary Asia | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR); Codes of conduct; Contract; Foreign workers; Garment industry |

| Crinis et al. (2019) | Corporate Social Responsibility, Human Rights and Clothing Workers in Bangladesh and Malaysia | Asian Studies Review | Fashion; Brand names; Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR); Anti-sweatshop movement; Migrant labor; Malaysia; Bangladesh |

| da Costa et al. (2017) | Cleaner Production Implementation in the Textile Sector: The Case of a Medium-sized Industry in Minas Gerais | Revista Eletronica Em Gestao Educacao E Tecnologia Ambiental | Cleaner production; Textile sector; Environmental management; Social Responsibility; Brazil |

| Da Giau et al. (2016) | Sustainability practices and web-based communication. An analysis of the Italian fashion industry | Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management | Corporate Social Responsibility; Communication; Supply chain management |

| Dabija et al. (2017) | Cross-cultural investigation of consumers’ generations attitudes towards purchase of environmentally friendly products in apparel retail | Studies in Business and Economics | Green marketing; Consumer; purchase behavior; Environmentally friendly products; Cross-country analysis; Apparel footwear and sportswear retail |

| de Abreu et al. (2012) | A comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility of textile firms in Brazil and China | Journal of Cleaner Production | Sustainable development; Emerging economies; Corporate Social Responsibility; Environmental management; Stakeholder; Textile industry; Brazil; China |

| De Angelis (2017) | The role of design similarity in consumers’ evaluation of new green products: An investigation of luxury fashion brands | Journal of Cleaner Production | Sustainability; Sustainable design; Sustainable consumption; Environmental sustainability; New green product; Design similarity; Luxury fashion brand |

| de Lagerie (2016) | Conflicts of Responsibility in the Globalized Textile Supply Chain. Lessons of a Tragedy | Journal of Consumer Policy | Factory collapse; Working conditions; Corporate Social Responsibility; Consumer activism; Qualitative study |

| de Lenne et al. (2017) | Media and sustainable apparel buying intention | Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management | Sustainability; Fast fashion; Social media; Theory of planned behavior; Sustainable apparel; Magazines |

| Desore et al. (2018) | An overview on corporate response towards sustainability issues in textile industry | Environment Development and Sustainability | Sustainability issues; Textile industry; Textile value chain; Sustainability strategies; Drivers and barriers; Strategic response |

| Di Benedetto (2017) | Corporate social responsibility as an emerging business model in fashion marketing | Journal of Global Fashion Marketing | Corporate social responsibility; Fashion; Marketing; Fashion merchandising; Customer relationship management; Sustainability |

| Diddi et al. (2016) | Corporate Social Responsibility in the Retail Apparel Context: Exploring Consumers’ Personal and Normative Influences on Patronage Intentions | Journal of Marketing Channels | Corporate Social Responsibility; Ethical behavior; Ethical Decision making; Moral norms; Retail apparel; United States; Values |

| Diddi et al. (2017) | Exploring the role of values and norms towards consumers’ intentions to patronize retail apparel brands engaged in corporate social responsibility | Fashion and Textiles | Corporate Social Responsibility; Value norms |

| Dodds et al. (2016) | Willingness to pay for environmentally linked clothing at an event: visibility, environmental certification, and level of environmental concern | Tourism Recreation Research | Willingness to pay; Festival marketing; Clothing; Fair trade certification; Sustainable consumption message |

| Dururu et al. (2015) | Enhancing engagement with community sector organizations working in sustainable waste management: A case study | Waste Management & Research | Third sector organizations; Sustainability; England; Sustainable waste management; Resource efficiency |

| Egels-Zanden et al. (2006) | Exploring the effects of union-NGO relationships on corporate responsibility: The case of the Swedish clean clothes campaign | Journal of Business Ethics | Clean Clothes Campaign; Corporate responsibility; Garment industry; Labor practice; Multi-national corporation; Non-governmental organization; Transnational corporation; Supplier relation; Union |

| Egels-Zanden et al. (2015) | Multiple institutional logics in union–NGO relations: private labor regulation in the Swedish Clean Clothes Campaign | Business Ethics: A European Review | None |

| Escobar-Rodriguez et al. (2017) | Facebook practices for business communication among fashion retailers | Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management | Word-of-mouth; Social networks; Marketing; Communities; Fashion retailing; E-commerce |

| Esmail et al. (2018) | The role of clothing in participation of persons with a physical disability: a scoping review protocol | Bmj Open | None |

| Fahimnia et al. (2018) | Greening versus resilience: A supply chain design perspective | Transportation Research Part E-Logistics and Transportation Review | Supply chain management; Green; Environmental sustainability; Robust; Network design; Elastic p-robust |

| Fang et al. (2010) | Sourcing in an Increasingly Expensive China: Four Swedish Cases | Journal of Business Ethics | China; CSR; Sourcing; Manufacturing; Price; Swedish companies; Textile and clothing industry (TCI) |

| Ferrell et al. (2016) | Ethics and Social Responsibility in Marketing Channels and Supply Chains: An Overview | Journal of Marketing Channels | Compliance; Corporate social responsibility; International Organization for Standardization; Marketing channels; Marketing ethics; Supply chain ethics; Supply chain management; Sustainability |

| Fontana (2018) | Corporate Social Responsibility as Stakeholder Engagement: Firm-NGO Collaboration in Sweden | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | Firm–NGO collaboration; Corporate social responsibility; Stakeholder engagement; Resource-based view; Sweden; Asylum applicants |

| Fornasiero et al. (2017) | Proposing an integrated LCA-SCM model to evaluate the sustainability of customization strategies. International | Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing | Supply chain; Customization; Modular life-cycle assessment; Simulation |

| Fransen et al. (2014) | Privatizing or Socializing Corporate Responsibility: Business Participation in Voluntary Programs | Business & Society | Labor standards; Globalization; Corporate responsibility; Multi-stakeholder governance; NGO |

| Fu et al. (2018) | Blockchain Enhanced Emission Trading Framework in Fashion Apparel Manufacturing Industry | Sustainability | Blockchain; Sustainability; Fashion apparel industry; Carbon trading; Energy economics industry |

| Garcia-Torres et al. (2017) | Effective Disclosure in the Fast-Fashion Industry: from Sustainability Reporting to Action | Sustainability | Sustainability reporting; Sustainability actions; United Nations SDGs; Fast-fashion industry; Supply chain sustainability; Sustainability scorecard |

| Gardas et al. (2018) | Modelling the challenges to sustainability in the textile and apparel (T&A) sector: A Delphi-DEMATEL approach | Sustainable Production and Consumption | Barriers; Sustainability; Textile and apparel supply chain; Multi-criteria decision making; India |

| Gardetti et al. (2013) | Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Luxury | Journal of Corporate Citizenship | Luxury; Sustainable; Cosmetics; Entrepreneurship; Latin America |

| Ghosh et al. (2012) | A comparative analysis of greening policies across supply chain structures | International Journal of Production Economics | Apparel industry; Green supply chains; Channel coordination; Game theory |

| Govindasamy et al. (2018) | Corporate Social Responsibility in Practice: The Case of Textile, Knitting and Garment Industries in Malaysia | Pertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanities | Barriers; Corporate Social Responsibility; Drivers; Malaysia; Textile |

| Guedes et al. (2017) | Corporate social responsibility: Competitiveness in the context of textile and fashion value chain | Environmental Engineering and Management Journal | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR); Ethical corporate management; SMEs; Sustainable development; Textile and fashion |

| Guercini et al. (2013) | Sustainability and Luxury | Journal of Corporate Citizenship | Luxury; Sustainability; Fashion; Supply chain |

| Hale et al. (2007) | Women Working Worldwide: transnational networks, corporate social responsibility and action research | Global Networks | Commodity chains; Garment production; New Labor; Inter- nationalism; Women workers’; Organizations; Transnational networking; Corporate social responsibility |

| Haque et al. (2015) | Corporate social responsibility, economic globalization and developing countries A case study of the ready-made garments industry in Bangladesh | Sustainability Accounting Management and Policy Journal | Bangladesh; Developing countries; Corporate social responsibility; Economic globalization; Ready-made garments |

| Hassan et al. (2017) | Quick dry ability of various quick drying polyester and wool fabrics assessed by a novel method | Drying Technology | Contact angle; FTIR; Quick drying; Test method; Textile fabrics |

| Heekang et al. (2018) | Environmentally friendly apparel products: the effects of value perceptions | Social Behavior & Personality: an international journal | Cause-effectiveness value; Monetary value; Environmentally conscious apparel products; Purchase intention |

| Henry et al. (2019) | Microfibers from apparel and home textiles: Prospects for including microplastics in environmental sustainability assessment | Science of the Total Environment | Plastic pollution; Synthetic fibers; Impact assessment; Marine ecosystems; Sewage sludge; Laundry |

| Hepburn et al. (2013) | In Patagonia (Clothing): A Complicated Greenness. Fashion Theory | The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture | Patagonia; Ethical consumption; Conservation; Sublime; Catalogue |

| Herva et al. (2008) | An approach for the application of the Ecological Footprint as environmental indicator in the textile sector | Journal of Hazardous Materials | Ecological Footprint; Textile sector; Environmental sustainability indicator; Simplified tool |

| Hischier (2018) | Car vs. Packaging-A First, Simple (Environmental) Sustainability Assessment of Our Changing Shopping Behavior | Sustainability | Sustainability assessment; Life cycle assessment; LCA; Online shopping; Packaging; Mobility; Lifestyles |

| Hong et al. (2019) | The impact of moral philosophy and moral intensity on purchase behavior toward sustainable textile and apparel products | Fashion and Textiles | Moral philosophy; Moral intensity; Purchase behavior; Sustainability; Organic products; Naturally dyed products |

| Huq et al. (2014) | Social sustainability in developing country suppliers. An exploratory study in the ready-made garments industry of Bangladesh | International Journal of Operations & Production Management | Bangladesh; Social sustainability; Developing country suppliers; Exploratory case study; Ready-made garments industry; Transaction cost economics |

| Hwang et al. (2016) | “Don’t buy this jacket” Consumer reaction toward anti-consumption apparel advertisement | Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management | Consumer attitudes; Anti-consumption; Patagonia; CSR; Advertisement; Purchase intensions |

| Jakhar (2015) | Performance evaluation and a flow allocation decision model for a sustainable supply chain of an apparel industry | Journal of Cleaner Production | Sustainable supply chain; Performance measures; Flow optimization; Structural equation modeling; Fuzzy analytic hierarchy process; Fuzzy multi-objective linear programming |

| James et al. (2019) | Bridging the double-gap in circularity. Addressing the intention-behavior disparity in fashion | Design Journal | Circular innovation; Design for longevity; Intention-behavior gap; Fashion product lifecycle |

| Jammulamadaka (2016) | Bombay textile mills: exploring CSR roots in colonial India | Journal of Management History | Bombay textile mills; Indian; CSR; Postcolonial |

| Jorgensen et al. (2012) | The shaping of environmental impacts from Danish production and consumption of clothing | Ecological Economics | Environmental management; Transnational; Supply chain; Product chain; Consumer practice; Clothing consumption |

| Joy et al. (2012) | Fast Fashion, Sustainability, and the Ethical Appeal of Luxury Brands | Fashion Theory-the Journal of Dress Body & Culture | Luxury brands; Fast fashion; Sustainability; Quality and consumer behavior |

| Jung et al. (2014) | A theoretical investigation of slow fashion: sustainable future of the apparel industry | International Journal of Consumer Studies | Slow fashion; Slow production; Slow consumption; Environmental sustainability; Small apparel business strategy; Scale development |

| Jung et al. (2016) | Sustainable Development of Slow Fashion Businesses: Customer Value Approach | Sustainability | Slow fashion; Fast fashion; Sustainability; Customer value; Price premium |

| Kang et al. (2013) | Environmentally sustainable textile and apparel consumption: the role of consumer knowledge, perceived consumer effectiveness and perceived personal relevance | International Journal of Consumer Studies | Consumer effectiveness; Consumer knowledge; Personal relevance; Sustainability; Textiles and apparel; theory of planned behavior |

| Karaosman et al. (2015) | Consumers’ responses to CSR in a cross-cultural setting | Cogent Business & Management | Corporate social responsibility; Consumer behavior; Qualitative research; Fashion industry; Cultural differences |

| Karaosman et al. (2017) | From a Systematic Literature Review to a Classification Framework: Sustainability Integration in Fashion Operations | Sustainability | Supply chain management; Fashion industry; Three-dimensional engineering framework; Fashion operations; Environmental sustainability; Social sustainability; Classification framework; Systematic literature review |

| Karell et al. (2019) | Addressing the Dialogue between Design. Sorting and Recycling in a Circular Economy | Design Journal | Circular economy; Clothing design; Design for recycling; Textile recycling; Textile sorting |

| Kemper et al. (2019) | Saving Water while Doing Business: Corporate Agenda-Setting and Water Sustainability | Water | Cotton; Water sustainability; Agenda setting; Water governance |

| Khurana et al. (2016) | Two decades of sustainable supply chain management in the fashion business, an appraisal | Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management | Fashion industry; Corporate social responsibility; Stakeholders; Supply chain management; Textile/clothing supply chains; Brands |

| Kim et al. (1998) | Environmental concern and apparel consumptions | Clothing and Textile Research Journal | Environmental attitude; Apparel consumption |

| Kim et al. (2015) | The heuristic-systemic model of sustainability stewardship: facilitating sustainability values, beliefs and practices with corporate social responsibility drives and eco-labels/indices | International Journal of Consumer Studies | Corporate social responsibility; Eco-label/index; Heuristic-systematic model; Sustainability stewardship; VBN Theory |

| Kim et al. (2017) | Sustainable Supply Chain Based on News Articles and Sustainability Reports: Text Mining with Leximancer and diction | Sustainability | Sustainability; Supply chain management (SCM); Triple bottom line; News articles; Sustainability report; Text mining; Leximancer |

| Klepp et al. (2018) | Nisseluelandet-The Impact of Local Clothes for the Survival of a Textile Industry in Norway | Fashion Practice-the Journal of Design Creative Process & the Fashion Industry | Local clothing; Home production; Textile industry; Handicrafts; Wool |

| Knudsen (2017) | How Do Domestic Regulatory Traditions Shape CSR in Large International US and UK Firms? | Global Policy | None |

| Knudsen (2018) | Government Regulation of International Corporate Social Responsibility in the US and the UK: How Domestic Institutions Shape Mandatory and Supportive Initiatives | British Journal of Industrial Relations | None |

| Koksal et al. (2017) | Social Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Textile and Apparel Industry-A Literature Review | Sustainability | SSCM; Supply chain management; Sourcing intermediary; Social sustainability; Apparel/clothing industry; Developing country suppliers |

| Koksal et al. (2018) | Social Sustainability in Apparel Supply Chains-The Role of the Sourcing Intermediary in a Developing Country | Sustainability | Sustainable supply chain management; Social sustainability; Textile/apparel industry |

| Kolstad et al. (2018) | Content-Based Recommendations for Sustainable Wardrobes Using Linked Open Data | Mobile Networks & Applications | Internet of things; Recommender systems; Content-based; Recommendation; Textile recycling; Linked open data; Bag of concepts; Purchase intention |

| Koszewska (2010) | CSR Standards as a Significant Factor Differentiating Textile and Clothing Goods | Fibers & Textiles in Eastern Europe | Corporate social responsibility; Textile & clothing goods; Consumer evaluation; Norms; Standards |

| Koszewska (2011) | Social and Eco-labelling of Textile and Clothing Goods as Means of Communication and Product Differentiation | Fibers & Textiles in Eastern Europe | Social labelling; Eco-labelling; Corporate social responsibility; Textile and clothing market; Fast fashion; Consumer behavior |

| Koszewska (2013) | A typology of Polish consumers and their behaviors in the market for sustainable textiles and clothing | International Journal of Consumer Studies | Socially responsible consumption; Typology; Textiles; Clothing; Consumer behavior; Sustainable |

| Kozlowski et al. (2012) | Environmental Impacts in the Fashion Industry: A Lifecycle and Stakeholder Framework | Journal of Corporate Citizenship | Fashion industry; Apparel; Environmental impacts; Life-cycle assessment; Stakeholder analysis; Corporate social responsibility; Supply chain management |

| Kozlowski et al. (2015) | Corporate sustainability reporting in the apparel industry. An analysis of indicators disclosed | International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management | CSR reporting; Sustainability reporting; Global reporting initiative; Sustainability indicators; Sustainable fashion |

| Lagoudis et al. (2015) | A framework for measuring carbon emissions for inbound transportation and distribution networks | Research in Transportation Business and Management | Carbon emissions; Green supply chain; Inbound logistics; Apparel industry |

| Laitala et al. (2018) | Does Use Matter? Comparison of Environmental Impacts of Clothing Based on Fiber Type | Sustainability | Sustainable clothing; Fiber properties; Clothing production; Fashion consumption; Maintenance; LCA; Environmental sustainability tools; Fiber ranking; Material selection |

| Lee et al. (2015) | The interactions of CSR, self-congruity and purchase intention among Chinese consumers | Australasian Marketing Journal | Corporate social responsibility; China; Fashion industry; Self-congruity; Purchase intention; Collectivism |

| Lee et al. (2015) | Impacts of sustainable value and business stewardship on lifestyle practices in clothing consumption. | Fashion and Textiles | Business stewardship; Sustainable lifestyle; Value; VALS framework |

| Lee et al. (2018) | Consumer responses to company disclosure of socially responsible efforts | Fashion and Textiles | California; Transparency in Supply Chains; Act; Socially responsible consumption; Consumer response; Website; Experiment |

| Lee et al. (2018) | Effects of multi-brand company’s CSR activities on purchase intention through a mediating role of corporate image and brand image | Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management | Brand image; Reciprocity; Corporate social responsibility; Corporate image; Multi-brand |

| Lee et al. (2018) | The effect of ethical climate and employees’ organizational citizenship behavior on US fashion retail organizations’ sustainability performance | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | Corporate social responsibility; Ethical climate; Organizational; Citizenship behavior; Sustainability; Performance |

| Lee et al. (2018) | The moral responsibility of corporate sustainability as perceived by fashion retail employees: a USA-China cross-cultural comparison study | Business Strategy and the Environment | Corporate sustainability; Cross-cultural studies; Fashion retail businesses; Moral responsibility; Organizational; Citizenship behavior |

| Lenzo et al. (2017) | Social Life Cycle Assessment in the Textile Sector: An Italian Case Study | Sustainability | Textile product; Social Life Cycle Assessment; Workers; Local communities; Social performances |

| Leoni (2017) | Social responsibility in practice: an Italian case from the early 20th century | Journal of Management History | Case studies; Corporate social responsibility; Italy; Family business; Management history; Accounting history |

| Li et al. (2014) | Governance of sustainable supply chains in the fast fashion industry | European Management Journal | Fast fashion; Sustainability; Corporate social responsibility; Supply chain governance |

| Li et al. (2017) | Environmental Management System Adoption and the Operational Performance of Firm in the Textile and Apparel Industry of China | Sustainability | Social sustainable performance; Operations; Event study; Textile and apparel industry |

| Liang et al. (2018) | Second-hand clothing consumption: A generational cohort analysis of the Chinese market | International Journal of Consumer Studies | Chinese consumers; Descriptive norm; Generational cohorts; Perceived concern; Perceived value; second-hand clothing |

| Lo et al. (2012) | The impact of environmental management systems on financial performance in fashion and textiles industries | International Journal of Production Economics | Environmental management systems; ISO 14000; Financial performance; Event study; Fashion and textiles industries |

| Lock et al. (2019) | Credible corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication predicts legitimacy Evidence from an experimental study | Corporate Communications | Legitimacy; Corporate social responsibility; Credibility; Experiment; Website |

| Lueg et al. (2015) | The Role of Corporate Sustainability in a Low-Cost Business Model-A Case Study in the Scandinavian Fashion Industry | Business Strategy and the Environment | Business model; Corporate social responsibility; Corporate sustainability; Sustainable development; CSR policies; Information disclosure; Labor practices; Public policy |

| Macchion et al. (2017) | Improving innovation performance through environmental practices in the fashion industry: the moderating effect of internationalization and the influence of collaboration | Production Planning & Control | Supply chain management; Environmental sustainability; Collaboration; Innovation management; Internationalization |

| Macchion et al. (2018) | Strategic approaches to sustainability in fashion supply chain management | Production Planning & Control | Supply chain management; Sustainability; Fashion; Environmental sustainability; Social sustainability |

| Majumdar et al. (2018) | Modeling the barriers of green supply chain management in small and medium enterprises A case of Indian clothing industry | Management of Environmental Quality | Interpretive structural modelling; Green supply chain; Clothing industry; Barriers; Indian SME |

| Maldini et al. (2019) | Assessing the impact of design strategies on clothing lifetimes, usage and volumes: The case of product personalization | Journal of Cleaner Production | Circular/sustainable design strategies; Clothing lifetimes; Clothing usage; Clothing volumes; Wardrobe studies; Personalized products |

| Mamic (2005) | Managing global supply chain: The sports footwear, apparel and retail sectors | Journal of Business Ethics | Code of Conduct; Supply chain management; Compliance; Corporate social responsibility; Management systems; Multinational enterprises |

| Mann et al. (2014) | Assessment of Leading Apparel Specialty Retailers’ CSR Practices as Communicated on Corporate Websites: Problems and Opportunities | Journal of Business Ethics | Corporate social responsibility; Apparel specialty retailer; Labor issues; Environmental issues |

| McNeill et al. (2015) | Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum: fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice | International Journal of Consumer Studies | Behavior; Clothing; Consumers; Eco; Fashion; Sustainable |

| McQueen et al. (2017) | Reducing laundering frequency to prolong the life of denim jeans | International Journal of Consumer Studies | Consumer habits; Denim jeans; Laundering; Textile degradation; Wear |

| Mena et al. (2016) | Theorization as institutional work: The dynamics of roles and practices | Human Relations | Corporate social responsibility; Institutional change; Institutional maintenance; Institutional transition; Private regulation; Private regulatory; Initiative |

| Merk (2009) | Jumping Scale and Bridging Space in the Era of Corporate Social Responsibility: cross-border labor struggles in the global garment industry | Third World Quarterly | None |

| Mezzadri (2014) | Back shoring, Local Sweatshop Regimes and CSR in India | Competition & Change | Garment commodity chain; Back shoring; Pan-Indian buyer exporters; Local sweatshop regime; Corporate social responsibility; India |

| Mezzadri (2014) | Indian Garment Clusters and CSR Norms: Incompatible Agendas at the Bottom of the Garment Commodity Chain | Oxford Development Studies | None |

| Micheletti et al. (2008) | Fashioning social justice through political consumerism, capitalism, and the internet | Cultural Studies | Political consumerism; Anti-sweatshop; Anti-slavery; Culture jamming; Market vulnerabilities; Social justice |

| Milne et al. (2013) | Small Business Implementation of CSR for Fair Labor Association Accreditation | Journal of Corporate Citizenship | Multi stakeholder initiative; Apparel industry; Corporate social responsibility; Labor compliance |

| Moon et al. (2018) | Environmentally friendly apparel products: the effects of value perceptions | Social Behavior and Personality | Cause-effectiveness value; Monetary value; Environmentally conscious; Apparel products; Purchase intention |

| Moore et al. (2004) | Systems thinking and green chemistry in the textile industry: concepts, technologies and benefits | Journal of Cleaner Production | Textile industry; Aquatic toxicity; Dyeing; Finishing; Systems thinking; Sustainable development; Globalization |

| Moore et al. (2012) | An Investigation into the Financial Return on Corporate Social Responsibility in the Apparel Industry | Journal of Corporate Citizenship | Corporate social responsibility; Financial return; Apparel industry |

| Moreira et al. (2015) | A conceptual framework to develop green textiles in the aeronautic completion industry: a case study in a large manufacturing company | Journal of Cleaner Production | Aircraft completion industry; Textiles; Sustainable products development; Eco-design |

| Moretto et al. (2018) | Designing a roadmap towards a sustainable supply chain: A focus on the fashion industry | Journal of Cleaner Production | Sustainability; Supply chain; Roadmap; Fashion; Luxury; CSR |

| Morgan et al. (2009) | An investigation of young fashion consumers’ disposal habits | International Journal of Consumer Studies | Fashion; Textile; Recycling; Consumers; Sustainable; Disposition |

| Na et al. (2015) | Investigating the sustainability of the Korean textile and fashion industry | International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology | Apparel reuse; Eco-materials; Eco-promotion |

| Nassivera et al. (2017) | Willingness to pay for organic cotton Consumer responsiveness to a corporate social responsibility initiative | British Food Journal | Consumer behavior; Corporate social responsibility; Organic cotton; Organic production; LISREL |

| Nayak et al. (2019) | Recent sustainable trends in Vietnam’s fashion supply chain | Journal of Cleaner Production | Sustainable supply chain management; Fashion sustainability; Textiles and garment; Emerging economy; Third-party logistics; Vietnam |

| Niu et al. (2018) | Outsource to an OEM or an ODM? Profitability and Sustainability Analysis of a Fashion Supply Chain | Journal of Systems Science and Systems Engineering | Outsourcing; Buy-back contract; Fashion supply chain; Nash bargaining |

| Normann et al. (2017) | Supplier perceptions of distributive justice in sustainable apparel sourcing | International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management | Code of conduct; Apparel industry; Sustainable sourcing; Qualitative study; Distributive justice; Assessment governance |

| O’Rourke et al. (2017) | Patagonia: Driving sustainable innovation by embracing tensions | California Management Review | Sustainability; Innovation; Supply chain; Environmental responsibility |

| Olsen et al. (2011) | Conscientious brand criteria: A framework and a case example from the clothing industry | Journal of Brand Management | Brand; Conscientious; CSR; Altruistic |

| Oncioiu et al. (2015) | White biotechnology—a fundamental factor for a sustainable development in Romanian SMEs | Romanian Biotechnological Letters | Green clothes; White biotechnology; Organic materials; SME’s; Environmental sustainability; Green clothes; White biotechnology; Organic materials; SME’s; Environmental sustainability |

| Paik et al. (2017) | Corporate Social Responsibility Performance and Outsourcing: The Case of the Bangladesh Tragedy | Journal of International Accounting Research | Corporate social responsibility; Worker safety agreement; Outsourcing; Bangladesh tragedy |

| Pal (2016) | Extended responsibility through servitization in PSS. An exploratory study of used-clothing sector | Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management | Clothing; Servitization; Textile/ clothing supply chains; PSS; Product-service system; Extended responsibility |

| Pangsapa et al. (2008) | Political economy of Southeast Asian borderlands: Migration, environment, and developing country firms | Journal of Contemporary Asia | Developing country companies; Environmental sustainability; Corporate responsibility; Labor unions; Migration; Global Compact |

| Panigrahi et al. (2018) | A stakeholders’ perspective on barriers to adopt sustainable practices in MSME supply chain: Issues and challenges in the textile sector | Research Journal of Textile and Apparel | Interpretive structural modeling; Sustainable supply chain management; Barriers to sustainable supply chain management; Sustainable supply chain practices |

| Park-Poaps et al. (2010) | Stakeholder Forces of Socially Responsible Supply Chain Management Orientation | Journal of Business Ethics | Supply chain; Clothing; Sweatshop; Social responsibility |

| Pather (2015) | Entrepreneurship and regional development: case of fashion industry growth in south Africa | Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues | Creative Industries; Fashion; Clusters; Local context |

| Pedersen et al. (2014) | From Resistance to Opportunity-Seeking: Strategic Responses to Institutional Pressures for Corporate Social Responsibility in the Nordic Fashion Industry | Journal of Business Ethics | Corporate social responsibility; Sustainability; Institutional pressures; Strategic responses |

| Pedersen et al. (2015) | Sustainability innovators and anchor draggers: a global expert study on sustainable fashion | Business Strategy and the Environment | Consumer behavior; Sustainability; Organizational change; Partnerships; Business models; Accountability |

| Pedersen et al. (2017) | The Role of Corporate Sustainability in a Low-Cost Business Model-A Case Study in the Scandinavian Fashion Industry | Social Responsibility Journal | Business model; Corporate social responsibility; Corporate sustainability; Sustainable development; CSR policies; Information disclosure; Labor practice; Public policy; Environmental policy; Risk management; Shareholder value; Stakeholder engagements; Supply chain |

| Pedersen et al. (2018) | Exploring the Relationship Between Business Model Innovation, Corporate Sustainability, and Organizational Values within the Fashion Industry | Journal of Business Ethics | Business model innovation; Corporate sustainability; Corporate social responsibility; Organizational values; Financial performance |

| Perry et al. (2013) | Conceptual framework development CSR implementation in fashion supply chains | International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management | Corporate Social Responsibility; Fashion; Supply chain management; Ethical sourcing |

| Perry et al. (2015) | Corporate Social Responsibility in Garment Sourcing Networks: Factory Management Perspectives on Ethical Trade in Sri Lanka | Journal of Business Ethics | Corporate social responsibility; Ethical sourcing; Retailing; Supply chain management; Sri Lanka |

| Pinheiro et al. (2019) | How to identify opportunities for improvement in the use of reverse logistics in clothing industries? A case study in a Brazilian cluster | Journal of Cleaner Production | Textile waste; Reverse logistics; Clothing industry; Cluster |

| Preuss et al. (2010) | Slipstreaming the Larger Boats: Social Responsibility in Medium-Sized Businesses | Journal of Business Ethics | Corporate social responsibility; Small and medium-sized enterprises; Owner–manager values; Consumer perceptions of CSR; Employee perceptions of CSR |

| Priyankara et al. (2018) | How Does Leader’s Support for Environment Promote Organizational Citizenship Behavior for Environment? A Multi-Theory Perspective | Sustainability | Autonomous motivation for environment; Employee green behavior; Leader’s support for environment; organizational citizenship behavior for environment; Perceived group’s green climate |

| Reilly et al. (2018) | External Communication About Sustainability: Corporate Social Responsibility Reports and Social Media Activity | Environmental Communication-a Journal of Nature and Culture | External communication; Corporate social responsibility; Sustainability; Social media |

| Reimers et al. (2016) | The academic conceptualization of ethical clothing Could it account for the attitude behavior gap? | Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management | Ethics; Social responsibility; Fashion; Clothing |

| Resta et al. (2016) | Enhancing environmental management in the textile sector: An Organizational-Life Cycle Assessment approach | Journal of Cleaner Production | Organizational Life Cycle Assessment (O- LCA); Environmental sustainability; Textile; Decision-making process; Environmental management |

| Ritch et al. (2012) | Accessing and affording sustainability: the experience of fashion consumption within young families | International Journal of Consumer Studies | Fashion consumption; Sustainability; Consumer behavior; Ethical retailing |

| Rodgers et al. (2017) | Results of a strategic science study to inform policies targeting extreme thinness standards in the fashion industry | International Journal of Eating Disorders | Eating disorders; Fashion; Models; Policy; Strategic |

| Roos et al. (2016) | A life cycle assessment (LCA)-based approach to guiding an industry sector towards sustainability: the case of the Swedish apparel sector | Journal of Cleaner Production | Life cycle assessment; Social assessment; Life cycle interpretation; Planetary boundaries; Actor-oriented advice; Textile |

| Ruwanpura (2016) | Garments without guilt? Uneven labor geographies and ethical trading-Sri Lankan labor perspectives | Journal of Economic Geography | Labor geography; Ethical trading; Sri Lanka; Corporate governance; Ethnography |

| Salcito et al. (2015) | Corporate human rights commitments and the psychology of business acceptance of human rights duties: a multi-industry analysis | International Journal of Human Rights | Corporate social responsibility; Human rights due diligence; Human rights; Policy; Protect; Respect; Remedy framework; UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights |

| Savino et al. (2018) | An extensive study to assess the sustainability drivers of production performances using a resource-based view and contingency analysis | Journal of Cleaner Production | Production performances; Environment; Safety; Social issues: Sustainability; Resource based view; Contingency perspective; Structural equation modelling; Quality management |

| Scheiber (2015) | Dressing up for Diffusion: Codes of Conduct in the German Textile and Apparel Industry, 1997–2010 | Journal of Business Ethics | Corporate code of ethics; Code of conduct; Diffusion; Discourse; Institutional theory; Infomediaries |

| Scheper (2017) | Labor Networks under Supply Chain Capitalism: The Politics of the Bangladesh Accord | Development & Change | None |

| Schmitt et al. (2012) | How to Earn Money by Doing Good! Shared Value in the Apparel Industry | Journal of Corporate Citizenship | Shared value; Value creation; Innovation; Sustainability; Apparel industry; Fair-trade; Value creation; Tree; Corporate social responsibility |

| Schuessler et al. (2019) | Governance of Labor Standards in Australian and German Garment Supply Chains: The Impact of Rana Plaza | ILR Review | Labor standards; Garment lead firms; Global supply chains; Focusing events; Rana Plaza |

| Shen et al. (2014) | Perception of fashion sustainability in online community | Journal of the Textile Institute | Sustainable fashion; Online forums; Consumer perception; Cross-time approach |

| Shen et al. (2015) | Impacts of Returning Unsold Products in Retail Outsourcing Fashion Supply Chain: A Sustainability Analysis | Sustainability | Return policy; Cost of physical return; Supply chain coordination; Sustainability analysis |

| Shen et al. (2015) | Evaluation of Barriers of Corporate Social Responsibility Using an Analytical Hierarchy Process under a Fuzzy Environment-A Textile Case | Sustainability | Barriers of CSR; Fuzzy AHP; Indian textiles |

| Shen et al. (2016) | Enhancing Economic Sustainability by Markdown Money Supply Contracts in the Fashion Industry: China vs USA | Sustainability | Markdown money policy; Fashion industry; Supply chain management; Cross-cultural study |

| Shubham et al. (2018) | Institutional pressure and the implementation of corporate environment practices: examining the mediating role of absorptive capacity | Journal of Knowledge Management | Environmental management strategy; Resource-based view; Absorptive capacity; Organizational capability; Corporate environmental practices; Partial least square-structural equation modelling |

| Siddiqui et al. (2016) | Human rights disasters, corporate accountability and the state Lessons learned from Rana Plaza | Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal | Bangladesh; Human rights; State; Corporate accountability |

| Song et al. (2017) | Perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward sustainable fashion: Application of Q and Q-R methodologies | International Journal of Consumer Studies | Q methodology; Q-R methodology; Sustainable consumer; Sustainable consumption; Sustainable fashion |

| Song et al. (2018) | A Human-Centered Approach to Green Apparel Advertising: Decision Tree Predictive Modeling of Consumer Choice | Sustainability | Decision tree; Green advertising; Green apparel; Green marketing; Segmentation; Sustainable fashion; Sustainability |

| Stevenson et al. (2018) | Modern slavery in supply chains: a secondary data analysis of detection, remediation and disclosure | Supply Chain Management-an International Journal | Sustainability; Clothing industry; Information transparency; Modern slavery; Supply chain information disclosure; Secondary data |

| Svensson (2009) | SCM ethics: conceptual framework and empirical illustrations | Supply Chain Management-an International Journal | Supply chain management; Scandinavia; Fashion industry; Telecommunications; Ethics; Corporate social responsibility |

| Tama et al. (2017) | University students’ attitude towards clothes in terms of environmental sustainability and slow fashion | Tekstil Ve Konfeksiyon | Environmental sustainability; Slow fashion; Fast fashion; University students; Environmental awareness |

| Testa et al. (2017) | Removing obstacles to the implementation of LCA among SMEs: A collective strategy for exploiting recycled wool | Journal of Cleaner Production | Small and medium enterprises; Life cycle assessment; Textile; Label; Collective action; Product; Environmental Footprint; Cluster |

| Thomas (2008) | From “Green Blur” to Eco fashion: Fashioning an Eco-lexicon. Fashion Theory | The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture | Eco fashion; Language; Lexicon; Ethical; Terminology |

| Thorisdottir et al. (2019) | Sustainability within Fashion Business Models: A Systematic Literature Review | Sustainability | Business model; Fashion; Sustainability; Measure; Driver; Report |

| Todeschini et al. (2017) | Innovative and sustainable business models in the fashion industry: Entrepreneurial drivers, opportunities, and challenges | Business Horizons | Business model innovation; Sustainable fashion; Born-sustainable; Startups; Social value creation; Slow fashion; Upcycling |

| Tran et al. (2016) | SMEs in their Own Right: The Views of Managers and Workers in Vietnamese Textiles, Garment, and Footwear Companies | Journal of Business Ethics | Socialist Vietnam; SME managers and Workers; Formal and informal CSR practices; Institutional theory; Labor–management–state relations |

| Wang et al. (2017) | Sustainability Analysis and Buy-Back Coordination in a Fashion Supply Chain with Price Competition and Demand Uncertainty | Sustainability | Supply chain sustainability; Buy-back coordination; Demand uncertainty; Price competition; Dual channel system |

| White et al. (2017) | CSR research in the apparel industry: A quantitative and qualitative review of existing literature | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | CSR in the apparel industry; CSR communication; Ethical supply chain management; Corporate social responsibility |

| Wijethilake et al. (2017) | Strategic responses to institutional pressures for sustainability. The role of management control systems | Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal | Sustainability; Institutional pressures; Management control systems; Strategic responses |

| Wong et al. (2017) | Corporate social responsibility (CSR) for ethical corporate identity management Framing CSR as a tool for managing the CSR-luxury paradox online | Corporate Communications | Luxury industry; CSR communication; Corporate identity; Corporate social responsibility; Corporate branding; Framing |

| Woo et al. (2016) | Apparel firms’ corporate social responsibility communications Cases of six firms from an institutional theory perspective | Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics | Communications; Cross-cultural marketing; Apparel; Corporate social responsibility; Institutional theory |

| Woo et al. (2016) | Culture Doesn’t Matter? The Impact of Apparel Companies’ Corporate Social Responsibility Practices on Brand Equity | Clothing and Textiles Research Journal | Corporate social responsibility; Brand equity; Apparel; Cross-cultural |

| Wu et al. (2012) | The effects of GSCM drivers and institutional pressures on GSCM practices in Taiwan’s textile and apparel industry | International Journal of Production Economics | Green supply chain management (GSCM); Green supply chain; Management drivers; Green supply chain; Management practices; Hierarchical moderated; Regression analysis; Institutional pressures |

| Wu et al. (2015) | The Impact of Integrated Practices of Lean, Green, and Social Management Systems on Firm Sustainability Performance-Evidence from Chinese Fashion Auto-Parts Suppliers | Sustainability | Lean; Green; Social; Sustainability; Triple Bottom Line (3BL) |

| Yadlapalli et al. (2018) | Socially responsible governance mechanisms for manufacturing firms in apparel supply chain | International Journal of Production Economics | Apparel supply chains; Bangladesh; Governance mechanisms; Socially responsible supply chains |

| Yang et al. (2017) | Analysis of the barriers in implementing environmental management system by interpretive structural modeling approach | Management Research Review | China; Environmental management system; Barriers analysis; Business ethics and sustainability; Textile and apparel industries; Interpretive structural modeling |

| Yang et al. (2017) | An Exploratory Study of the Mechanism of Sustainable Value Creation in the Luxury Fashion Industry | Sustainability | Sustainability; Sustainable value; Value co-creation; Supply chain; Case study |

| Yasmin (2014) | Burning death traps made in Bangladesh: who is to blame? | Labor Law Journal | None |

| Zhang et al. (2015) | Life cycle assessment of cotton T-shirts in China | International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment | Cleaner production; Clothing; Consumer behavior; Cotton textile; Environmental management; Laundry washing; Life cycle assessment; Sustainability |

| Zurga et al. (2015) | Environmentally sustainable apparel acquisition and disposal behaviors among Slovenian consumers | Autex Research Journal | Environmentally sustainable; Consumer behavior; Apparel consumption; Apparel acquisition; Apparel disposal; Environment; Slovenia |

References

- Levitt, T. The Globalization of Markets. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1983, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gronroos, C. Service Management and Marketing: Managing the Service Profit Logic, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–522. [Google Scholar]

- Fashion United. Global Fashion. Available online: https://fashionunited.com/global-fashion-industry-statistics (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- European Environment Agency. News, Private Consumptions; Textile. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/highlights/private-consumption-textiles-eus-fourth-1 (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Foroohar, R. Newsweek Fabulous Fashion. Available online: https://www.newsweek.com/fabulous-fashion-121093 (accessed on 20 November 2018).

- Clean Clothes Campaign. Improving Working Conditions in the Global Garment Industry. Available online: https://cleanclothes.org/fashions-problems (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- World Commission on Environment and Development Report. Our Common Future. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2017).

- Lash, W. Competitive Advantage on a Warming Planet. Harward Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. State and Outlook 2015 Assessment of Global Megatrend. 2015, pp. 1–140. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/soer/2015/global/action-download-pdf (accessed on 27 October 2016).

- Nordic Fashion Association. Background. Available online: www.nordicfashionassociation.com/background (accessed on 10 December 2016).

- de Brito, M.P.; Carbone, V.; Blanquart, C.M. Towards a sustainable fashion retail supply chain in Europe: Organisation and Performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 114, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Black, S. The Sustainable Fashion Handbook; Thames & Hudson Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fashion Revolution. Consumer Survey Report. 2018, pp. 1–45. Available online: https://www.fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/201118_FashRev_ConsumerSurvey_2018.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2018).

- Kruse, E. Copenhagen Fashion Summit The Magazine Global Fashion Agenda: 2018. Available online: https://www.globalfashionagenda.com/publications-and-policy/pulse-of-the-industry/ (accessed on 20 May 2018).

- Thorisdottir, T.S.; Johannsdottir, L. Sustainability within Fashion Business Models: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Remy, N.; Speelman, E.; Swartz, S. Style That’s Sustainable: A new Fast-Fashion Formula. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/our-insights/style-thats-sustainable-a-new-fast-fashion-formula (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. 2017. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications/a-new-textiles-economy-redesigning-fashions-future (accessed on 4 February 2018).

- Cobbing, M.; Vicaire, Y. Timeout for Fashion; Greenpeace: Hamburg, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Claudio, L. Waste Couture. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Preuss, L.; Perschke, J. Slipstreaming the Larger Boats: Social Responsibility in Medium-Sized Businesses. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92, 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Shah, J. A comparative analysis of greening policies across supply chain structures. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 568–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, N.P.; Prado, J.F.; Fonseca, A. Cleaner Production Implementation in the Textile Sector: The Case of a Medium-sized Industry in Minas Gerais. Rev. Eletron. Gest. Educ. E Tecnol. Ambient. 2017, 21, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimnia, B.; Jabbarzadeh, A.; Sarkis, J. Greening versus resilience: A supply chain design perspective. Transp. Res. Part E-Logist. Transp. Rev. 2018, 119, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.L.; De Silva, I.; Hartmann, S. An Investigation into the Financial Return on Corporate Social Responsibility in the Apparel Industry. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2012, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, A.; Bardecki, M.; Searcy, C. Environmental Impacts in the Fashion Industry: A Life-cycle and Stakeholder Framework. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2012, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, G.H.; Lee, B.; Krumwiede, K.R. Corporate Social Responsibility Performance and Outsourcing: The Case of the Bangladesh Tragedy. J. Int. Account. Res. 2017, 16, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouinard, Y.; Stanley, V. The Responsible Company What We’ve Learned from Patagonia’s First 40 Years; Bell, S., Ed.; Patagonia Books: Ventura, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gam, H.J. Are fashion-conscious consumers more likely to adopt eco-friendly clothing? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2011, 15, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K. Eco-clothing, Consumer Identity and Ideology. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M.A.; Amatulli, C. The role of design similarity in consumers´evaluation of new green products. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 1515–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Benedetto, C.A. Corporate social responsibility as an emerging business model in fashion marketing. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2017, 8, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Zheng, J.H.; Chow, P.S.; Chow, K.Y. Perception of fashion sustainability in online community. J. Text. Inst. 2014, 105, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, K.; Kinley, T. Green spirit: Consumer empathies for green apparel. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.; Jin, B.H. Culture Doesn’t Matter? The Impact of Apparel Companies’ Corporate Social Responsibility Practices on Brand Equity. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2016, 34, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszewska, M. Social and Eco-labelling of Textile and Clothing Goods as Means of Communication and Product Differentiation. Fibrestext. East. Eur. 2011, 19, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Lee, Y. The interactions of CSR, self-congruity and purchase intention among Chinese consumers. Australas. Mark. J. 2015, 23, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritch, E.L.; Schröder, M.J. Accessing and affording sustainability: The experience of fashion consumption within young families. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haski- Leventhal, D. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility; SAGE: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Diddi, S.; Niehm, L.S. Exploring the role of values and norms towards consumers’ intentions to patronize retail apparel brands engaged in corporate social responsibility (CSR). Fashion Text. 2017, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karaosman, H.; Morales-Alonso, G.; Grijalvo, M. Consumers’ responses to CSR in a cross-cultural setting. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebner, D.; Baumgartner, R.J. The relationship between Sustainable Development and Corporate Social Responsibility. In Proceedings of the Corporate Responsibility Research Conference, Dublin, Ireland, 4–5 September 2006; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Concepts, Research and Practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Vladimirova, D.; Holgado, M.; Fossen, K.; Yang, M.; Silva, E.A.; Barlow, C.Y. Business Model Innovation for sustainability: Towards a Unified perspective for Creation of Sustainable Business Models. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I.; Chirico, A. The role of sustainability key performance indicators (KPIs) in implementing sustainable strategies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lozano, R. Envisioning sustainability three-dimensionally. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1838–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopfer, K.; Foster, J.; Puts, J. Micro-Meso-Macro. Evol. Econ. 2014, 14, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steurer, R.; Langer, M.; Konrad, A.; Martinuzzi, A. Corporations, Stakeholders and Sustainable Development I: A Theoretical Exploration of Business-Society Relations. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 61, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A. The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latapí Agudelo, M.; Jóhannsdóttir, L.; Davídsdóttir, B. A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Commission. Green Paper Promoting a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility; Corner, P., Ed.; European Union An official website of the European Union. 2001, pp. 1–26. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/DOC_01_9 (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Blowfield, M.; Murray, A. Corporate Responsibility, 3rd ed.; United States of America by Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 1–143. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits. Corp. Ethics Corp. Gov. 2007, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, S. The Performance of Italian Clothing Firms for Shareholders, Workers and Public Administrations: An Econometric Analysis. I. J. Account. Res. Audit Pract. 2011, 10, 20–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlstrom, J. Corporate Response to CSO Criticism: Decoupling the Corporate Responsibility Discourse from Business Practice. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit and Explicit” CSR: A Conceptual Framework for a Comparative Understanding of Corporate Social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rasche, A.; Morsing, M.; Moon, J. Corporate Social Responsibility; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/education-sustainable-development/what-is-esd/sd#:~:text=Sustainability%20is%20often%20thought%20of,research%20and%20technology%20transfer%2C%20education (accessed on 11 August 2020).

- Lucas, S. The Five Dimensions of Sustainability. Environ. Politics 2009, 18, 539–556. [Google Scholar]

- Lafferty, W.M.; Langhelle, O. Sustainable Development as Concept and Norm; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, M. CSR and Sustainability; Greenleaf Publishing Limited.: Sheffield, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Robért, K.; Schmidt-Bleek, B.; Aloisi de Larderel, J.; Basile, G.; Jansen, J.; Kuehr, R.; Price Thomas, P.; Suzuki, M.; Hawken, P.; Wackernagel, M. Strategic sustainable development—Selection, design and synergies of applied tools. J. Clean. Prod. 2002, 10, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, P. Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman, T.; Farrington, J. What is Sustainability? Sustainability 2010, 2, 3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drexhage, J.; Murphy, D. Sustainable Development: From Brundtland to Rio 2012; International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD): New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. 25 Years ago, I coined the phrase "The Triple Bottom Line" Here’s why it’s time to rethink it. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2018, 6, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- White, M. Sustainability: I know it when I see it. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; DesJardine, M. Business sustainability: It is about time. Strateg. Organ. 2014, 12, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.; Johnstone-Luis, M.; Mayer, C.; Stroehle, J.C. The Board’s Rolen in Sustainability. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2020, 98, 1–152. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, D. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility, 4th ed.; Sage Publication Inc.: London, UK, 2017; p. 716. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Global Compact. Guide to Corporate Sustainability. Shaping A Sustainable Future. 2014. Available online: https://d306pr3pise04h.cloudfront.net/docs/publications%2FUN_Global_Compact_Guide_to_Corporate_Sustainability.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2016).

- Sage Publication. Sociology. A Unique Way to View the World. 2017, pp. 1–24. Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/86855_Ch_1.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Baumgartner, R.J.; Ebner, D. Corporate Sustainability Strategies: Sustainability Profiles and Maturity Levels. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 769–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, T.; Bruce, M. Fashion Marketing Contemporary Issues, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Internal Market. Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/index_en (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Global Fashion Agenda. Online event: Virginijus Sinkevičius, EU Commissioner for Environment, Oceans and Fisheries. July 2020 ed.; European Commission Audiovisual Service. 2020. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/company/globalfashionagenda/videos/native/urn:li:ugcPost:6687355661967257601/ (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Gordon, J.; Hill, C. Sustainable Fashion, Past, Present and Future; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 9780857851840. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. A New Circular Economy Action Plan For a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:9903b325-6388-11ea-b735-01aa75ed71a1.0017.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 16 July 2020).

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; Sage Publication Ltd.: London, UK, 2009; pp. 1–731. ISBN 978-2-4129-3118-2. [Google Scholar]

- Jesson, J.K.; Matheson, L.; Lacey, F.M. Doing Your Literature Review; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2012; pp. 1–269. ISBN 978-1-84920-592-4. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design, 4th ed.; Sage Publication Inc: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Collis, J.; Hussey, R. Business Research, 4th ed.; Palgrave Macmillian: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–351. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th ed.; Sage Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia, M.; Testa, F.; Bianchi, L.; Iraldo, F.; Frey, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Competitiveness within SMEs of the Fashion Industry: Evidence from Italy and France. Sustainability 2014, 6, 872–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haque, M.Z.; Azmat, F. Corporate social responsibility, economic globalization and developing countries A case study of the ready-made garments industry in Bangladesh. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2015, 6, 166–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olsen, L.E.; Peretz, A. Conscientious brand criteria: A framework and a case example from the clothing industry. J. Brand Manag. 2011, 18, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park-Poaps, H.; Rees, K. Stakeholder Forces of Socially Responsible Supply Chain Management Orientation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.R.G.; Lauesen, L.M.; Kourula, A. Back to basics: Exploring perceptions of stakeholders within the Swedish fashion industry. Social Responsibility Journal 2017, 13, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, A.; Sinha, S. Modeling the barriers of green supply chain management in small and medium enterprises A case of Indian clothing industry. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2018, 29, 1110–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, A. A Triple Bottom Line Approach for Measuring Supply Chains Sustainability Using Data Envelopment Analysis. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 6, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Macchion, L.; Moretto, A.; Caniato, F.; Caridi, M.; Danese, P.; Spina, G.; Vinelli, A. Improving innovation performance through environmental practices in the fashion industry: The moderating effect of internationalization and the influence of collaboration. Prod. Plan. Control 2017, 28, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R.; Akbari, M.; Far, S.M. Recent sustainable trends in Vietnam’s fashion supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheper, C. Labour Networks under Supply Chain Capitalism: The Politics of the Bangladesh Accord. Dev. Chang. 2017, 48, 1069–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Li, Q.Y. Impacts of Returning Unsold Products in Retail Outsourcing Fashion Supply Chain: A Sustainability Analysis. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1172–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koksal, D.; Strahle, J.; Muller, M. Social Sustainability in Apparel Supply ChainsThe Role of the Sourcing Intermediary in a Developing Country. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, D.; Kim, S. Sustainable Supply Chain Based on News Articles and Sustainability Reports: Text Mining with Leximancer and DICTION. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferrell, O.C.; Ferrell, L. Ethics and Social Responsibility in Marketing Channels and Supply Chains: An Overview. J. Mark. Channels 2016, 23, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.; Jin, B. Apparel firms’ corporate social responsibility communications Cases of six firms from an institutional theory perspective. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2016, 28, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, I.; Schulz-Knappe, C. Credible corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication predicts legitimacy Evidence from an experimental study. Corp. Commun. 2019, 24, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu, M.C.S.; de Castro, F.; Soares, F.D.; da Silva, J.C.L. A comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility of textile firms in Brazil and China. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 20, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.J.; Jin, B. Sustainable Development of Slow Fashion Businesses: Customer Value Approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, C.L.; Nielsen, A.E.; Valentini, C. CSR research in the apparel industry: A quantitative and qualitative review of existing literature. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadlapalli, A.; Rahman, S.; Gunasekaran, A. Socially responsible governance mechanisms for manufacturing firms in apparel supply chains. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 196, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Larsson, A.; Mark-Herbert, C. Implementing a collective code of conduct-CSC9000T in Chinese textile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 74, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.Y.; Dhanesh, G.S. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) for ethical corporate identity management Framing CSR as a tool for managing the CSR-luxury paradox online. Corp. Commun. 2017, 22, 420–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M.; Byun, S.E.; Kim, H.; Hoggle, K. Assessment of Leading Apparel Specialty Retailers’ CSR Practices as Communicated on Corporate Websites: Problems and Opportunities. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 599–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangsapa, P.; Smith, M.J. Political economy of Southeast Asian borderlands: Migration, environment, and developing country firms. J. Contemp. Asia 2008, 38, 485–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagoudis, I.N.; Shakri, A.R. A framework for measuring carbon emissions for inbound transportation and distribution networks. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2015, 17, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shen, L.X.; Govindan, K.; Shankar, M. Evaluation of Barriers of Corporate Social Responsibility Using an Analytical Hierarchy Process under a Fuzzy Environment A Textile Case. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3493–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perry, P.; Wood, S.; Fernie, J. Corporate Social Responsibility in Garment Sourcing Networks: Factory Management Perspectives on Ethical Trade in Sri Lanka. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, P.; Towers, N. Conceptual framework development CSR implementation in fashion supply chains. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2013, 43, 478–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindasamy, V.; Suresh, K. Corporate Social Responsibility in Practice: The Case of Textile, Knitting and Garment Industries in Malaysia. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2018, 26, 2643–2656. [Google Scholar]

- Todeschini, B.V.; Cortimiglia, M.N.; Callegaro-de-Menezes, D.; Ghezzi, A. Innovative and sustainable business models in the fashion industry: Entrepreneurial drivers, opportunities, and challenges. Bus. Horizons. 2017, 60, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]