1. Introduction

The United Nations (UN) Agenda [

1] proposes 17 ambitious sustainable development goals (SDGs) for a better life (as disclosed in

Appendix A,

Table A1) envisioning a mixture of global thinking and local acting. Additionally, the UN Agenda opens up the considerations about sustainable development and the call for new approaches to measure performance, to develop business models oriented toward sustainability, and to integrate sustainable procedures with the reporting structures.

Sometimes, improvement towards one goal might reinforce or even harm progress towards another SDG and it is, therefore, critical to understand the SDGs’ relationships and to construct the most original arrangement to achieve the maximum for each goal. The interlinked nature of the goals has been researched and confirmed by recent studies [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

At the business level, the preference on reporting SDGs is through non-financial information, under a variety of labels, recurrently as: Sustainability Report, Corporate Responsibility Report, Integrated Report, CSR Report, Non-financial Performance Statement, for the reason that the multi-faceted construction of the SDGs is analogous with non-financial reporting, which includes information concerning economic performance, environmental and social impact, health matters, demonstrating the link between corporate strategy and commitment to a sustainable global economy [

8].

A valuable non-financial report should include both positive and negative impact on the surroundings where the company is based, the company’s environmental and social data, and the relationship to sustainable development. In these circumstances, the European Union (EU) decided to make mandatory the disclosure of non-financial information provided by large companies and groups (defined based on the number of employees, namely, higher than 500), publishing in 2014 the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (Directive 2014/95/EU) [

9].

The relationship between sustainability practices and the financial performance of companies has attracted much attention among researchers [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Although the sustainability reports have been increasing in number [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26], several authors have expressed concern with respect to the degree to which sustainability reports accurately and completely portray corporate social and environmental impacts [

24,

27,

28].

The current study aims to determine to what extent the corporates’ financial indicators impact the quality of sustainability reporting based on SDGs in the case of chemical companies operating in Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries during 2015–2019. To this end, firstly, we developed and assigned an SDG score using information disclosed in the non-financial reports, considering both qualitative and quantitative aspects. Secondly, we extracted financial data in order to measure their influence on the SDGs reporting, by applying four multiple linear regression models, that have the previously computed SDG score series as dependent variable, demonstrating the accounting rigorousness to be an essential feature for attaining financial results consistent with the goals of sustainable development [

29,

30,

31,

32].

The main conclusions highlight the preoccupation shown by companies on reporting the goals, with an emphasis on guaranteeing decent and proper work conditions for employees, the implementation of a sustainable supply chain, promoting activities for reducing the pollution of water, air, as well as waste management. The corresponding SDGs were allocated with the maximum score level (5), this also being explained by the fact that the analysed companies operate in the chemical sector. With respect to the influence of financial indicators on the quality of SDGs reporting, return on assets has the lowest impact on the quality of sustainability reporting based on the SDG score, whereas the contribution of research and development (R&D) costs and other intangibles resulted to be substantial, as a consequence of the essential role played by R&D in the advancements to innovation and technology within the chemical industry.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The next section reviews the relevant literature debating SDGs reporting and sets the background of the study. This is followed by the presentation of data and research methodology used in the investigation. The fourth section shows the empirical findings and discusses the results. The final section provides some concluding remarks, implications and limitations of the research.

This exploration might be noteworthy from several perspectives: for scholars, by enriching the academic literature discussing the association of financial and non-financial reporting related to SDGs; for investors, with an increased interest in environmental, social and governance information by helping them understand what SDG reporting they should be looking for and requesting from the companies they intend to invest in; for decision makers, by offering assistance in ascertaining the financial indicators that have the greatest impact in contributing to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals.

2. Literature Review

Sustainable development refers to the overall impact of sustainable action and was initially only characterised as responsible use of natural resources [

33]. The idea of sustainability resides in three pillars: “economic development,” “social development” and “environmental protection,” known as the “Triple Bottom Line” approach. In 1996, Deegan and Rankin [

34] alerted that only a display of environmental information is solely favourable to the corporation’s image, but in order to be sustainable, companies should extensively act on all three pillars of contemporary performance: financial, environmental and social, generating a helix of transformational effects, objectively reporting both positive and negative facts and figures.

The pathways to sustainable development will not be identified through a top-down approach, but through highly strengthening our era by building a networked problem-solving system that engages the world’s universities, businesses, nongovernmental organisations, governments, and especially young people, who should become the experts and leaders of these new and profoundly challenging times [

35]. The involvement of the new talented generations will contribute to creating symbiosis and harmony between the economic, social and environmental pillars [

36], in order for them to naturally and synchronically progress together as a triple helix. This approach comes as a necessity in a global context characterised by the influence of social media and information technology, where problem-solving networks involving governments, international institutions, private business, academia working together for achieving sustainable development will play a crucial role in the years ahead.

Sustainable development goals may require a new way of thinking, because the goals are complex and interconnected, and their success likely depends on partnerships between business, governments and civil society [

24]. According to PwC’s survey [

26], more and more companies perceive strategic value in SDG; this study, based on 470 companies from 17 countries operating in six broad industries, endorsed PwC to conclude that 62% companies mentioned SDGs in their reporting. An additional study conducted by Corporate Citizenship agency [

23] found that 41% of the 240 analysed companies have done some form of mapping or prioritization of the SDGs to which they most contribute. On the other hand, KPMG’s survey published in 2018 [

25] underlines that 75% of 250 largest companies included in their study discuss the impact of SDGs on their business, but reporting is predominantly unbalanced with most entities providing their positive impacts, but not the negative effects.

The SDGs make available a common framework that guides corporations to be more accountable about their influences and performance to their stakeholders, as well as to improve partnership and collaboration opportunities to address sustainable challenges. Different companies have been employing different approaches to identify and report on their contributions to the SDGs, as well as to identify opportunities to align their business strategies with the SDGs, for the reason that each corporation has its own personality and history just as a person does. Its body of knowledge and expertise is unique and its circumstances are characteristic to its own experience and environment [

37,

38]. Mori et al.’s research [

38] found that significant and transparent disclosure on the measurement of any contribution made with respect to the SDGs is not yet common practice among the assessed companies because non-financial reporting is newly regulated. In Europe, the UN Parliament adopted in 2014 the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (Directive 2014/95/EU10), which requires Europe’s largest corporations to publish sustainable reports. This directive is a cornerstone of the evolution of sustainability reporting, but not the only frontier in which such reporting is taking shape as a well-regulated framework [

39,

40]. Managing corporate sustainability entails the analysis of the impacts of social and environmental initiatives on the overall corporate profitability [

41].

The benefits of sustainability reporting go beyond relating business financial risk and opportunity to performance along economic, social and planet dimensions and establishing certification to operate. Sustainability disclosure can serve as a differentiator in competitive industries and foster investors’ confidence, trust and employees’ loyalty [

42]. Tenuta [

43] advocates that the sustainability report is the most operative instrument to relate the business with its stakeholders. Investors often consider a company’s sustainability disclosures in their assessment of portfolios [

44,

45], and reporting may provide corporations with better access to capital [

46]. In a review of more than 7000 sustainability reports from around the globe, researchers found that sustainability disclosures are being used to help analysts determine corporations’ values and that sustainability disclosures may reduce forecast inaccuracy by approximately 10% [

47].

Decades ago, Belkaoui [

48] and Sturdivant and Ginter [

49] investigated the relationship between sustainability, in terms of corporate social responsibility, and performance, validating not only an association between management values and corporate social responsiveness, but also that companies with strong social involvement generally enjoy better financial performance than their less responsive industry counterparts. Similarly, the positive relationship between sustainability and performance was confirmed by Ameer and Othman [

11], as well as Alshehhi et al. [

10] when they investigated the sustainability practices influence on financial ratios, defined as return on assets, profit before taxation, and cash flow from operations. Bnouni [

50] demonstrates a positive, but marginal, relationship between sustainability (as CSR) and financial performance across 80 French small and medium-sized enterprises, and reaches the conclusion that the positive effect of sustainability does not just occur in large organisations. Systematic review piloted by Muhmad and Muhamad [

51] highlighted that about 96% of the publications reported a positive relationship between sustainability practices and the financial performance of companies.

On the contrary, Lopez et al. [

52] studies the influence of economic, environmental and social indicators of 55 companies on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index and 55 companies on the Dow Jones Global Index, concluding with a negative relationship between sustainability and corporate performance within the analysed time frame of 1998–2004.

Contemporary times lead to improvements of reporting non-financial aspects with respect to environment, people, ethics and governance, and, nowadays, the corporate social responsibility is shaped and converted into sustainable development goals (SDGs). In 2017, KPMG [

40] identified the increasing role of the SDGs for corporate responsibility as a key trend and the study published by PwC in 2015 [

53] acknowledged that 71% of surveyed businesses plan on developing measures to attempt meeting the SDGs. Therefore, the academic literature is growing in assessing the progress in the corporates’ accomplishment of SDGs, either in single-country analyses [

36,

38,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58] or multi-countries analyses [

28,

59,

60].

Investigations of SDGs by industries are conducted by Cosma et al. [

61] proving considerations from SDG reporting by European banks, Jones et al. [

62] outlining the concept of SDG in information technology and communications (ITC), and Rao et al. [

63] addressing the contribution of agriculture and allied activities towards achieving the SDGs. At the chemical industry-level, Zimara and Eidam [

58] examined the sustainability disclosure highlighting the diverse structure of the 14 selected companies’ reports. Complementarily, this research states that more than 70% of the companies commit themselves to the principles on human rights, labour standards, environmental protection, and fight against corruption.

The model of sustainable development is unfamiliar for companies operating in CEE countries and, in some way, this is considered a targeted development challenge [

64,

65]. For countries part of CEE, the post-communist era (1990 upward) has come with many structural ups and downs accompanied by uncertainties; these countries face socioeconomic difficulties, as high unemployment rates, high rate of emigration, low purchasing power of households, political hesitations and the quality of legislation, to name a few.

To our knowledge, non-financial reporting, in general, and SDGs reporting, in particular, are scarce when it comes to European emerging economies. In this setting, the current investigation intends to provide answers to the following research questions concerning chemical companies operating in Czech Republic (CZ), Hungary (HU), Poland (PL), Romania (RO) and Slovakia (SK):

Employing a score-based approach, what are these companies’ advancements in achieving the SDGs?

To what degree do financial data influence the SDGs reporting, measured in terms of the previously defined score?

3. Research Methodology

The research methodology is structured hereafter in three main subsections. The first relates to the data collection process and sample details, the second corresponds to the SDG score computation based on content analysis, and a third section refers to the empirical approach for testing the influence of financial indicators on sustainability reporting, based on several multiple linear regression models.

The analysis is focused on the chemical sector companies. Generally, the SDG prioritization depends on the company’s industry level. There are industries where a direct link can be easily identified between one goal and the characteristics of the companies’ activities within a sector, such as food companies—SDG 2 Zero hunger, pharmaceutical firms—SDG 3 Good health and well-being, or energy corporates—SDG 7 Affordable and clean energy [

66], but also industries with harmful effects on the environment, implying indirect connections to more different goals. Moreover, the chemical sector is an important supplier of products and services to practically every other industry, being one of the most diversified of all industries [

67], and thus it interacts with an extensive number of SDGs [

68], such as SDG 6 Clean water and sanitation, SDG 7 Affordable and clean energy and SDG 13 Climate action. According to the European Environment Agency (EEA) [

69], the chemical industry is one of the top 10 main polluting industries, in terms of air and water pollution, as well as waste generation, hence having a significant impact on the sustainable development goals.

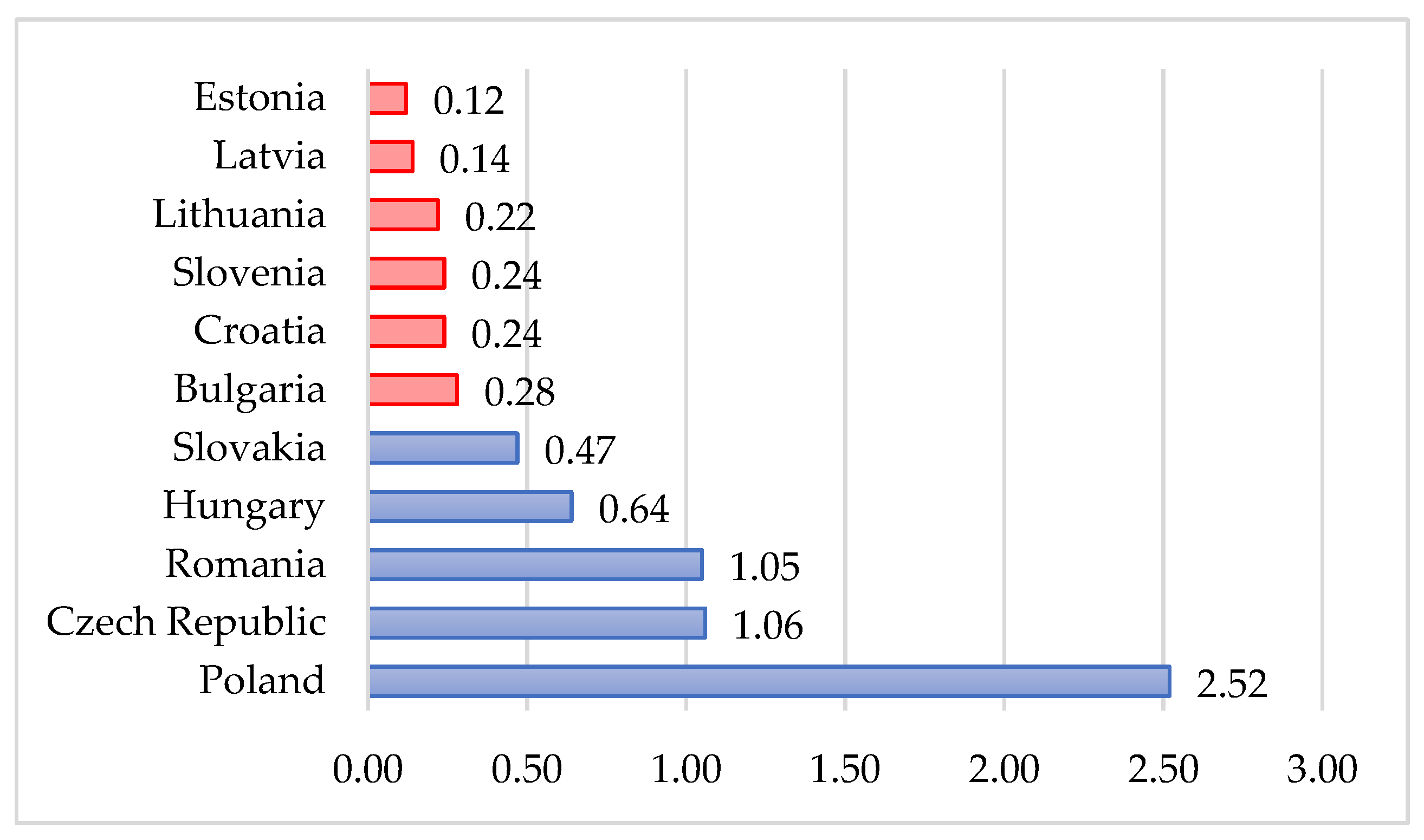

In addition, with reference to the choice of the 5 CEE countries included in the analysis, based on the same data provided by the EEA interactive platform, the countries’ industrial pollution profiles show that Poland, Czech Republic, Romania, Hungary and Slovakia are the greatest contributors from the Central and Eastern European region in terms of gross value added (GVA), as revealed in

Figure 1.

Accordingly, CEE countries add up to 6.98% of the European GVA from industry, of which 5.74%—representing 82.23% of the CEE countries contribution—comes from the first five countries included in the analysed sample (PL, CZ, RO, HU and SK). The rest of 93.02% of the total GVA from industrial activities is generated by the other European countries.

3.1. Data Collection and Sample Information

The sample of firms used in this study was initially drawn from the ISI Emerging Markets Group’s EMIS platform database [

70], the first 20 companies operating in the chemicals industry and sorted by their operating revenue being selected for each of the 5 CEE countries included in the analysis. We focus on the time frame of 2015–2019, which is the period immediately following the UN announcement of the 17 sustainable development goals. After identifying the firms, several screens were applied in selecting the final sample. Firstly, we checked for the availability of the companies’ reports in English on their websites. To this respect, all types of reports were considered, from sustainability and CSR reports to annual financial reports, and other information published on their websites. Secondly, if individual data were not available, the group reports were used instead. In order to ensure the quality of the research data, we excluded from the initial sample firms where information was non-available or missing, as well as those showing reports written in other languages than English (to avoid any biases associated with translation) [

71]. Hence, of the 100 companies considered at first, only 47 were left in the final sample used for the SDG score analysis, after applying the selection criteria previously mentioned, resulting in a number of 171 firm-year observations as disclosed in

Table 1. Also,

Appendix B,

Table A2 shows the remaining firms by countries and operating revenues.

The following step of the selection methodology is related to the second part of the study, referring to the analysis of the influence that financial information exerts on sustainability reporting. For this section, the previous 47 firms included in the SDG score analysis were subsequently checked for the availability of financial data disclosed in the annual reports of the considered period 2015–2019. As indicated in

Appendix B,

Table A2, this additional selection criterion led to a remaining number of 38 companies which published the necessary financial indicators for the multiple linear regression analysis, resulting in a number of 153 firm-year observations. Along with the above, as part of the regression analysis, the resulted outliers have been truncated, leading to a final sample of 36 firms and 147 firm-year observations. The country and year breakdown of this sample are presented in

Table 2.

Both samples reveal a balanced structure of the firm-year observations on countries and years, with the greatest representation from Hungary (22.81% for the SDG score and 25.85% for the regression), and the lowest representation from the Czech Republic for the SDG score analysis (17.54%) and equally from the Czech Republic and Romania for the regression analysis, with 16.33% each.

In terms of the number of documents that have been analysed during the data collection process,

Table 3 emphasises a total of 166 reports, with details regarding their types, structure, as well as their number by years during 2015–2019.

Figure 2 reveals the graphical representation of the reports’ structure by type.

For 2018, 38 reports were included in the sample, this also being the greatest number analysed within the 5 years. The lowest number of reports is shown in 2015. In respect of their types, between 2017–2019 the number of non-financial reports was the highest, whereas in 2015–2016 the annual financial reports had the greatest representation.

The structure of the analysed reports is almost equally spread between the sustainability reports, other non-financial reports, and annual financial reports (approximately 27% for each category), complemented by the CSR reports with 12% and integrated reports with approximately 7%. These findings are similar to the ones obtained by Yu et al. [

57].

In addition to the hand collection of information related to the SDG score, the companies’ annual financial statements were analysed in order to extract the financial indicators used for defining the variables included in the regression models for the second part of the study. During the process of hand-collecting the financial indicators, only the information disclosed in the restated version of the financial statements was considered, in such cases. Moreover, as the financial indicators were extracted from reports disclosing data in various currencies, all the amounts have been converted in EUR using the official exchange rates published by the European Central Bank [

72] for each year end between 2015–2019.

3.2. Methods Used for the Assessment of the Quality SDG Score Based on a Content Analysis Approach

The first step in applying the research methods consists in determining an annual SDG score for the sampled firms, designed to assess the quality of the companies’ sustainability reporting. For gathering the necessary information on SDGs disclosed in the corporates’ reports, a textual and content analysis on the selected reports was performed [

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78]. This is a widely adopted technique for such academic research [

79], as it is designed “for making replicable and valid inferences from texts (or other meaningful matter) to the contexts of their use” (p. 18), and it consists of a scientific tool that “provides new insights, increases a researcher’s understanding of particular phenomena, or informs practical actions” [

74] (p. 18). In terms of analysing corporate reports, Wen [

80] draws the attention on three main methods that are usually used to analyse texts: individual word-count systems that quantify word frequencies and other text characteristics, human-based content analysis which allows researchers to look more closely at the aspects disclosed in the documents, and computer-aided qualitative data analysis systems that use artificial intelligence to analyse text documents [

80], citing [

81]. Considering these options, similar to Cosma et al. [

61], the manual content analysis and interpretation was the chosen method for this study, without the use of any specific software. Taking into account that information regarding the SDGs found in the firms’ reports is frequently associated with the 17 icons corresponding to the goals, the use of content analysis software might not have led to accurate results.

Thus, all public reports of the companies available on their official websites were screened in full and reviewed [

75,

82], in order to identify the sustainable development goals that they are addressing, as well as the qualitative and quantitative targets, efforts, or measurements for each SDG [

56,

78]. By applying search queries for the occurrence of key words, such as “sustainable,” “sustainability,” “SDG,” the textual analysis [

75,

76] was conducted in order to determine whether the sampled companies addressed the SDGs in their reports. This was followed by the content analysis for the score’s assessment. The entire data collection process was carefully supervised and cross validated between all team members to ensure the quality, comparability and reliability of the research [

78].

In order to measure the engagement of the selected chemical sector companies in reporting their SDG achievements, a score-based approach using a scale from 0 to 5 was developed and applied, considering the targets, the efforts and the measurements companies have set and have monitored during the analysed period, as shown in

Table 4 (detailed information and examples are provided in

Appendix C,

Table A3). The used scoring methodology is consistent with other similar studies [

61,

75,

77,

78,

83,

84].

Consequently, the SDG score was assigned to a sustainable development goal either by allocating it based on the targets and actions addressing it, or by taking into account the clearly specified SDGs from the analysed reports. This process was applied for each firm-year observation. Furthermore, a score was allocated to an SDG if companies disclosed in their reports that at least one target or indicator addressing that particular SDG was impacted by the firms’ actions.

Additionally, as shown in

Table 4, the score was assigned differentially based on qualitative and quantitative aspects reported by companies. Such a distinction was necessary as determining the quantitative goals indicates the extent to which the concept of sustainable development is being implemented [

63]. In line with the previous, setting quantitative targets and monitoring their achievements reflects the effective practices applied by companies in integrating the sustainability development goals with their business strategies [

77].

As previously mentioned, identifying each SDG was based on three possible scenarios: clearly specified SGDs in the sustainability/annual reports, allocated SDGs based on the targets set by the United Nations or both mentioned and allocated goals.

As revealed in

Figure 3, almost a quarter of the total number of companies clearly specified the SDGs they were addressing, 14% particularly mentioned some SDGs, but they also presented information about other SDGs without specifying them, while most of the firms preferred to disclose sustainability aspects without naming the related SDGs.

3.3. Methods Applied for the Analysis of the Influence of Financial Information on Sustainability Reporting Based on the Multiple Linear Regression Model

The academic literature shows many empirical studies that have examined the relationship between companies’ social performance and their financial performance [

85,

86]. The findings of such research papers are mostly mixed. Some studies found a negative relationship [

87,

88], some found a positive relationship [

17,

85,

89,

90,

91], and others reported inconclusive or insignificant results [

92]. However, given the broad range of motives for corporate social responsibility activities, it might not come as surprising that empirical studies analysing this association find mixed results [

93].

In this context, for the analysis of the extent to which financial information is influencing sustainable development reporting, a methodology based on multiple linear regression models is applied. This section mentions hereafter the research design used in the study, starting with the definition and measurement of the variables, and afterwards presenting the research models.

3.3.1. Defining the Dependent Variable—Measurement of the Sustainable Development Indicator

The dependent variable, namely the sustainable development goals quality score (SDGS), is defined as a measure of the sustainability reporting quality and it is derived from the previous section of the methodology. Using similar methods to the ones applied in prior studies [

61,

77,

78,

83], SDGS is a continuous variable constructed as follows:

where i = firm, t = year,

j = goals from 1 to 17 and SDG = score from 0 to 5 assigned for each one of the 17 SDGs.

3.3.2. Defining the Independent Variables—Measurement of the Financial Performance Indicators

Consistent with prior studies as indicated below next to each variable, the independent continuous variables used in the regression models are defined in

Table 5.

To avoid scale problems, we applied the common practice of using the natural logarithm on some of the variables [

99].

3.3.3. Defining the Control Variables

Following previous research, our study controlled for firm size [

86,

87,

92,

95,

96,

100,

101] and leverage [

17,

91,

94,

95,

96,

100,

101]. Additionally, we use two dichotomous variables to control for the availability of sustainability reporting [

77], and whether the firms’ auditor is a Big 4 company or not, assuming that statements assured by the Big 4 auditing companies are of higher quality [

101]. Moreover, in order to reduce concerns on any associations between dependent and independent variables, dummy variables for countries and years were used as well [

99,

102,

103]. No control for industry was necessary, as all the sampled companies are operating in the same sector. Accordingly, all control variables included in the regression models are defined as disclosed in

Table 6.

The choice of the financial indicator as a measure of the corporates’ size was influenced by the Pearson correlation coefficient obtained for the variables. Although most of the similar academic work uses total assets [

85,

86,

95,

101,

104,

105] and/or sales [

85,

92,

105] as control variables for firm size, these financial indicators did not represent an option in our case, as both resulted to be strongly positively correlated with two of the independent variables, INT and RDOINT, with a Pearson correlation coefficient above 0.8, significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). Hence, to avoid any multicollinearity issues [

106], considering the recommended Pearson cut-off value [

107], a variable based on the value of property, plant and equipment was chosen instead, as an alternative measurement of size.

3.3.4. Regression Models

Therefore, based on the previously defined variables, the following multiple linear regression models were developed and applied:

where i = firm; t = year; k = 1 to 4 (number of countries minus one); all variables included in the equations are consistent with the prior definitions.

For compiling the multiple linear regression models, as well as other necessary statistical procedures, IBM SPSS Statistics 27 was used as software resource. In order to ensure the statistical validity of the regression models, several procedures were applied for testing the following assumptions [

108]:

there is a linear relationship between the dependent variable and each of the independent variables, as well as the dependent variable and the independent variables collectively; this was checked by plotting a scatterplot of the studentized residuals against the (unstandardized) predicted values for the first assumption, and partial regression plots between each independent variable and the dependent variable for the second;

data show homoscedasticity of residuals, also checked using the plot of the studentized residuals against the unstandardized predicted values;

data show no multicollinearity, insuring there are no problems in understanding which independent variable contributes to the variance explained in the dependent variable, as well as technical issues in calculating a multiple regression model; we detect for multicollinearity through an inspection of correlation coefficients and Tolerance/ variance inflation factor (VIF) values [

109], as well as the analysis of the Pearson correlation matrix;

there are no significant outliers, high leverage points or highly influential points; this assumption was verified by: detecting outliers using casewise diagnostics and studentized deleted residuals, and examining whether these residuals are greater than ±3 standard deviations; checking for leverage points considering leverage values less than 0.2 as safe, 0.2 to less than 0.5 as risky, and values of 0.5 and above as dangerous [

110]; and checking for influential points using Cook’s distance as a measure of influence, by determining if any values are above 1 [

111]; furthermore, in order to detect any multivariate outliers, the Mahalanobis distance was used [

112];

the residuals are approximately normally distributed, checked by inspecting histograms with superimposed normal curve and P-P plot, as well as normal Q-Q plot of the studentized residuals.

After verifying the resulted outliers based on the abovementioned procedures, 6 of the 153 firm-year observations were truncated, leading to the final sample of 147 observations. The 6 deleted observations included the ones showing a negative value of stockholder’s equity [

100]. There were no studentized deleted residuals greater than ±3 standard deviations, no leverage values greater than 0.2, and values for Cook’s distance above 1. The mentioned truncated observations were multivariate outliers detected by applying the Mahalanobis distance.

The results of the tests revealed that all the assumptions were verified and all the statistical criteria were met in order to run the multiple linear regressions. Details related to these results are found in

Appendix D.

5. Conclusions and Limitations

This study was undertaken in order to investigate to what extent financial indicators influence sustainability reporting on SDGs, and which are those financial indicators that have the highest impact on the quality of SDG reporting. For conducting the analysis, the methodology involved two approaches, one related to determining the SDG reporting quality score, which consists of the dependent variable included in the second part of the research, and the other was based on applying multiple linear regression models involving financial performance indicators.

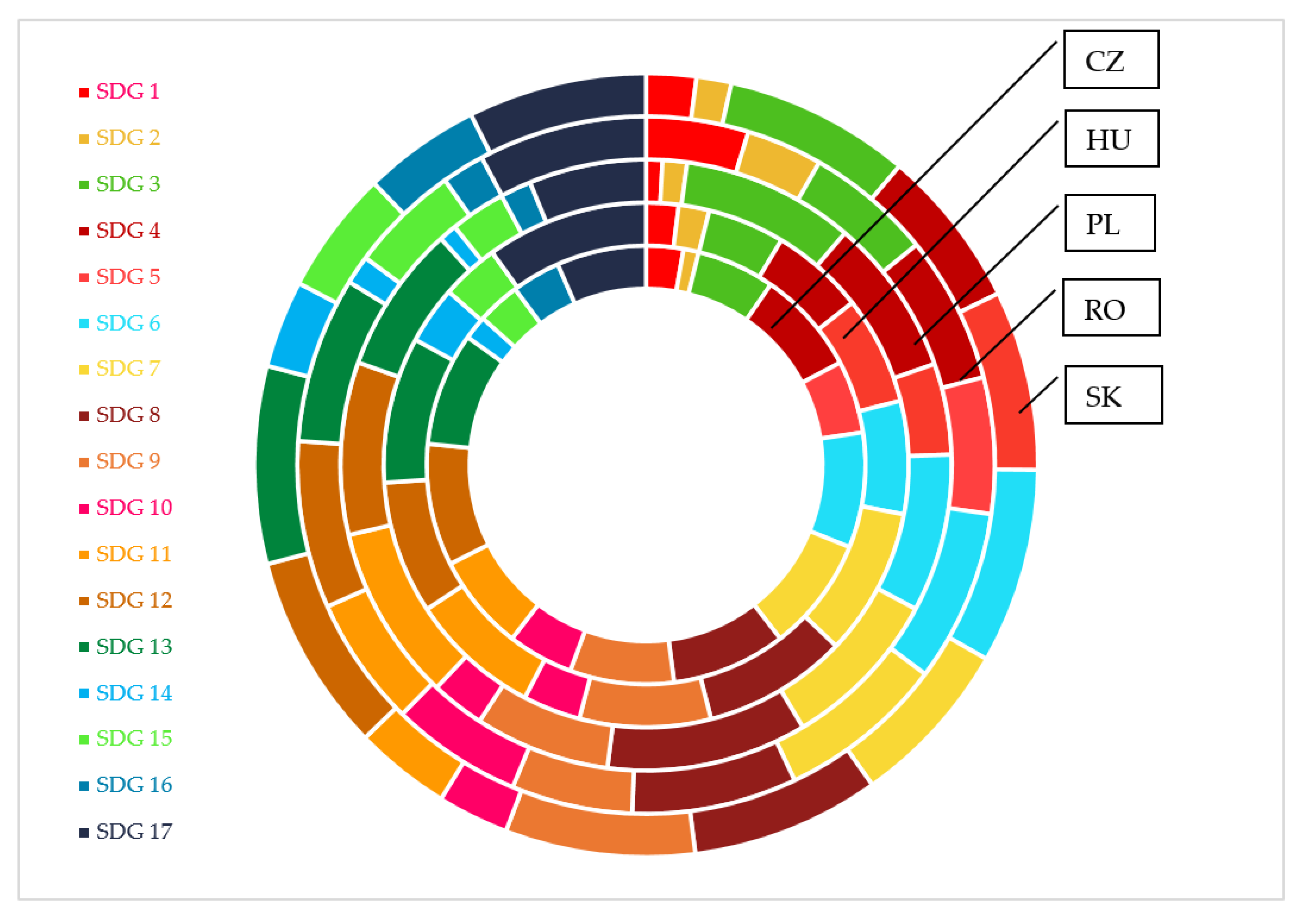

The findings related to the first section emphasise the firms’ interest in reporting SDGs by countries, by the SDGs that were allocated with the maximum score level (5), as well as interlinkages among SDGs.

The country-level analysis indicated a great interest in promoting activities for reducing the pollution of water, air and managing the waste accordingly to SDG 6, SDG 13 and SDG 12, respectively. However, the diversity of the preoccupation shown by companies on reporting the goals is also noteworthy. Thus, considering all the SDGs, Hungary and Poland reached the maximum score on five different goals (SDG 7, SDG 13, SDG 14, SDG 9, SDG 17 versus SDG 3, SDG 4, SDG 11, SDG 8, SDG 12), Slovakia and Romania achieved the highest score for three various SDGs (SDG 5, SDG 15, SDG 16 versus SDG 1, SDG 2, SGD 10), while the Czech Republic had only one goal with the best score (SDG 6).

Then, analysis was conducted to assess the number of companies that succeeded to reach the maximum score of 5 for each reported SDG, allocated only if both quantitative target and quantitative/qualitative measurement of the results were disclosed, hence showing the companies’ commitment to achieving the sustainability development goals. The information related to promoting decent work (SDG 8) has obtained the maximum score by most of the companies, and an active involvement of companies was noticed in reporting quantitative targets on water and waste management (SDG 6 and SDG 12), gas emissions (SDG 13) and even energy consumption (SDG 7) together with their achievement stages. Operating in a polluting sector, chemical companies understood the sustainable environment’s importance and they try to eliminate the negative impacts by setting targets and monitoring the results. On the contrary, just a few companies showed interest in achieving the highest score for SDG 1, SDG 2 and SDG 14.

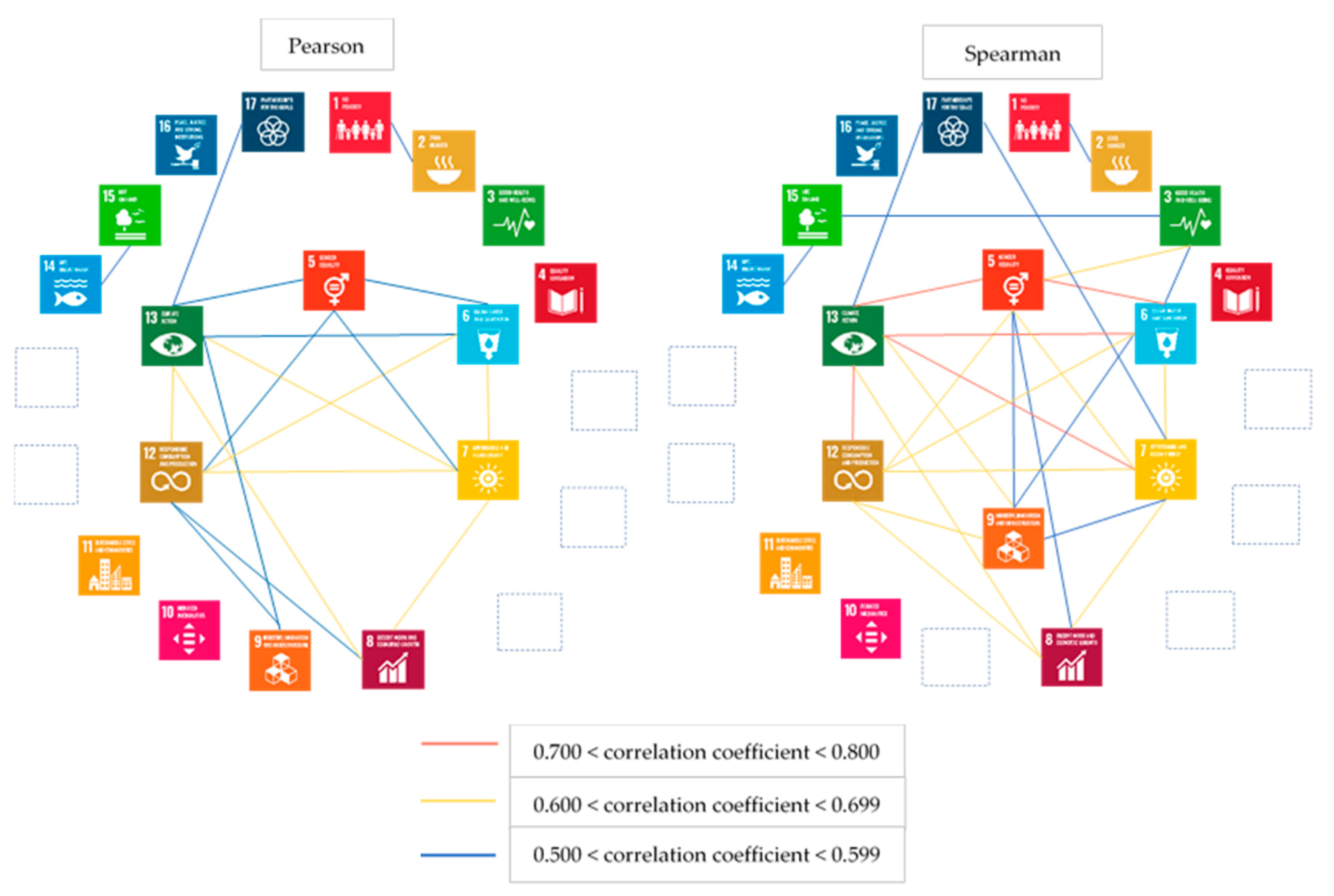

In many cases the achievement of one goal’s targets depends on the progress of another SDG due to the interactive nature of the goals. Hence, using Pearson and Spearman correlation methods, the interactions among SDGs were tested. The findings were consistent with recent studies, as indicated in

Section 4.1.2. All the correlation coefficients were positive, highlighting direct associations between SDGs, and it was identified that there is a core structure of association relationships between five goals (SDG 5, SDG 6, SDG 7, SDG 12 and SDG 13) with some extension to another goal (SDG 9) under the Spearman correlation matrix. The statistics also revealed connections between SDG 1 and SDG 2 on one hand, and SDG 14 and SDG 15 on the other hand. Detailed information was provided regarding the linkages among the targets of each of these sustainable development goals.

In addition to the previous findings related to the SDGs analysis, the second section of the paper discloses the results obtained after applying the four multiple regression models. These were developed by regressing the SDGS dependent variable to each of the four independent variables based on the following financial indicators: return on assets (ROA), cash flows divided by turnover (CFTURN), interest expenses (INT), research and development costs and other intangibles (RDOINT). To control for the availability of sustainability reporting, leverage, firms’ size, as well as the influence of Big 4 auditors, the regression models also involved the following control variables: SR, LEV, PPE, AUD. Moreover, we used dummy variables to control for the fixed effects of countries and years (COUNTRY and YEAR). Our findings in terms of the models’ goodness of fit show that of the four independent variables, ROA has the lowest contribution on the quality of sustainability reporting based on the SDG score, starting from an R

2 of 56.6%, followed by 57.4% for CFTURN, then 59.6% obtained for the regression on INT, and the highest R

2 of 63.4% achieved for the regression on RDOINT, respectively. All four models are statistically significant at the 1% level. Hence, contrary to Seifert et al. [

90], who found no effects of the R&D intensity, RDOINT is the most influential variable in explaining the variation in the companies’ SDG score, which might be explained by the association between research and development advancements and their contribution to innovation and technology. With respect to the coefficients’ statistics, both INT and RDOINT show a positive and statistically significant impact on SDGS at the level of 1%. The findings related to the INT variable are contrary to those indicated by Orens et al. [

96], which were highlighting a negative relationship between the cost of financing and CSR disclosure. However, these results are statistically significant, as opposed to Hoepner et al. [

98], who found that the relationship between sustainability performance and the cost of debt is insignificant.

On the opposite side, the study provides empirical evidence that ROA has a negative association with SDGS, but the result is not significant, which is consistent with some of the previous research [

88,

92,

119]. Similar to Seifert et al. [

90], for CFTURN we found a positive but very weak influence on the dependent variable variation explained by the model, significant at the 10% level.

The regression models’ coefficients show that the country plays a statistically significant part in almost all the cases in the evolution of the SDG score, showing negative coefficients for all the other analysed countries compared to RO (which was set as the reference country), with the exception of the SK coefficient in model 1. In terms of the years’ impact on the variation of the SDGs reporting quality, all the obtained coefficients are positive and show an increasing trend both in terms of values and statistical significance. These results reflect an improvement on the quality of sustainability reporting based on SDGs compared to 2015, when the goals were first set by the UN.

Like all empirical research, our study has several limitations which have to be considered while interpreting its results [

86]. First of all, the research is based on a limited sample, which was a consequence of the reports’ unavailability for half of the companies initially considered in the analysis. This was also related to the fact that the sample selection did not take into account whether the firms were listed or private, as including only publicly trading entities would have probably led to an increase of the reports’ availability, hence, of the sample. Secondly, subjectivity is an issue in any approach that involves textual or content analysis as a research method. This is also the case when dealing with data hand collection, which is prone to biases.

Further studies might focus on expanding the sample and emphasising a comparison between private and listed companies. Additionally, a development of the SDG score methodology could be suitable for an in-depth assessment of the SDGs’ reporting quality.