Abstract

The United Nations’ 2030 Agenda has further propelled the need for the private sector to engage with sustainable development. Corporate sustainability research seeks to specifically address this; however, extant literature highlights a paucity of research on how this occurs. In this study, we utilise an emerging process that has been identified to support managers in addressing sustainability—the corporate sustainability assessment (CSA). Utilising an in-depth case study and qualitative data collection, this study highlights how CSAs are a systematic and comprehensive approach to guide managers in how they can address sustainability. This study empirically examines three distinct but interconnected aspects of the CSA including the sustainability governance system, measurement of sustainability performance and sustainability reporting. With scant empirical studies on both CSAs and multinational enterprises (MNEs) operating in emerging markets, this study provides unique insights into two key traits of MNEs to understand the interplay between home- and host-country contexts and the industrial sector the MNE is operating within.

1. Introduction

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) articulate the shared vision of the global community towards achieving sustainable development [1]. A central aspect of achieving sustainable development is the involvement of the private sector [2], particularly in developing countries where there may be institutional voids, sensitive or poorly protected environmental conditions and significant gaps in the implementation of regulatory guidance for addressing sustainability [3,4,5,6]. While there is a range of potential private sector actors, including small and medium enterprises [7], that can hold a critical role in sustainable development, multinational enterprises (MNEs), specifically, can have a significant role in contributing within developing countries due to their control over expansive supply chains and production facilities across developing regions, as well as controlling substantial networks of business partners providing different inputs into their supply chains [1,8,9,10]. This is particularly the case in the Asia Pacific region, where substantial numbers of MNEs are operating and have a critical role in driving sustainable development [1].

While it has often been postulated that the conditions within developing countries do not support the transition towards sustainable development [3,5,11] nor the greater involvement of the private sector [4,8], a range of studies are beginning to indicate an increasing trend of companies operating in developing countries adopting corporate sustainability (CS), including social responsibility initiatives [3,12,13]. Indeed, a recent report released by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) [14] indicates a rapid uptake of sustainability reporting in developing countries with growth from five percent in 2001 to 33 percent in 2013. Despite this uptake, the GRI study emphasises that high level company engagement in CS is not “linear” with the actual impact for addressing sustainability issues [14]. Rather, there is a tendency for sustainability to be seen as a proxy for good governance and attracting foreign investment, instead of contributing to sustainable development and societal impact [13,14].

A range of studies have identified the need to strengthen knowledge and capacity building of individuals and organisations in developing countries for better engagement in sustainability (e.g., [5,12,15]). The authors of [5] (p. 136) further highlight this, arguing that research at the local-level is needed in order to “properly understand and manage the impacts of local decisions on a wider scale”. The authors of [8] take this one step further, arguing that in order to maximise multinational companies’ contribution to sustainable development, further research is required to not only understand their home-country context but also the host-country context. More specifically, [12] emphasised that the processes companies used in developing countries prioritise sustainability issues, categories and indicators to be addressed in their CS initiatives remains unknown. While leading global bodies keep calling for a significant increase of companies involved in developing countries to support achievement of the SDGs [16,17], a distinct paucity of empirical studies identifying how these companies engage with sustainable development is evident; this includes across the Asia Pacific region.

Engaging specifically with this topic, this study examines the management processes being adopted by a major multinational company when operationalising their CS initiatives in Malaysia. It does so through a lens of a corporate sustainability assessment (CSA), which has been identified within the extant literature as a process for operationalising sustainability. Digi, a telecommunication company operating in Malaysia and part of Telenor Group headquartered in Norway, is examined as an in-depth case study. By doing so, this research is able to present a systematic empirical analysis on the company’s pathways to integrate the sustainable development agenda into its operations, utilising a process framework for CSA. This case study provides unique insights into two key traits to understand how MNEs engage with sustainable development. Specifically, the interplay between home- and host-country contexts and the industrial sector the MNE is operating within [8].

It is worth noting that the Information Communication Technology (ICT) sector has been identified as a sector that has sought to proactively respond to the international call for business mobilisation to address the SDGs. The International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the United Nations specialised agency for information and communication technologies, announced that the ICT sector had broadly pledged a commitment to actively contribute in achieving SDGs [18]. Reports on the adoption of sustainable development within the private sector have also highlighted the ICT industry as one of the leading industries committed to the UN SDGs [18,19,20,21]. Despite this, very little sustainability research has been undertaken on the broader sector, or sub-sector (e.g., [21,22,23]), including within the developing country context

In Section 2, an analytical review is undertaken of CSA and its key aspects to establish the broader framing of this study. This is followed by the methodology adopted for data collection, in Section 3. Utilising an in-depth case study and qualitative data collection method, the study highlights the CSA process adopted by Digi when addressing sustainable development across their business operations.

2. Literature Review: Corporate Sustainability Assessments

The corporate sustainability research domain has focused on translating and implementing sustainable development at the corporate level [24]. However, previous studies have indicated a paucity of research addressing “how” sustainability is managed within organisations [25,26]. While the c-suite level has increasingly recognised this as a business priority [27], managers and practitioners have been identified as being ill-equipped when it comes to the integration of sustainability into business activities [28].

Looking more specifically at the operational level, CSA has emerged as a potential tool within CS research to guide managers on how they address sustainability through their management practices. As [29] recently postulated, CSA is “a platform from which the private sector can implement systematic processes to address sustainability” [29] (p. 1). Indeed, [30] (p. 3) argue that sustainability assessment at the company level can be seen as “an instrument to evaluate organisational performance to assist decision-makers in determining which actions should or should not be taken in an attempt to contribute to sustainable development”. A range of research has shown the broader utility of CSA supporting the private sector to engage with sustainable development (e.g., [1,16,29,31]).

While CSA has only emerged more recently as a potential tool or process to guide managers addressing sustainability, it finds its theoretical roots in the impact assessment domain [31]. This research domain focuses largely on predictive assessments of impacts associated with projects, rather than ongoing and adaptive management practices of organisations [32]. More recently and reflecting the greater engagement within the broader CS literature, CSAs have been examined from a range of business discipline contexts including accounting [33], management accounting [25], management [34] and even into engineering [35].

While the body of literature is growing on the use of the CSA as a tool to inform decision-making for sustainable development, it nevertheless remains used across differing contexts with different meanings. Specifically, within the extant literature, there appears to be two distinct perspectives on CSA as either a method for an evaluation of sustainability performance (e.g., [36,37]) or as a broader management process (e.g., [25,30,33,38]). In this research, we adopt the second perspective, with the CSA as a holistic management process adopted by companies to address sustainability within their business operations [29,30,31].

In taking this perspective, this study acknowledges a significant limitation in many of the previous studies that examined the use of CSAs by organisations from a management perspective. Specifically, the holistic nature of the process implies the need for comprehensively examining the entire nature to account for connections and inter-relationships between different aspects of the CSA. Some of the seminal studies examining CSAs within an organisational perspective (i.e., [29,38,39]) have been limited by a narrow empirical lens focused on several aspects of the CSA, or have been limited by a largely theoretical perspective (i.e., [25,33]). This study seeks to move beyond a purely theoretical examination of CSA and a narrow focus on particular elements of the overall process, rather integrating and examining the entire CSA process through an empirical example.

With this perspective, three key interconnected concepts are identified, framing how CSA is implemented within companies. This includes through a sustainability governance system [33,40,41], measurement of sustainability performance [33,42,43] and sustainability reporting activities [25,33,43]. Building from these points, this study examines these concepts, detailing the empirical implementation of each concept at company level through examining the practices of Digi.

2.1. Theory Framework: Corporate Sustainability Assessments (CSA)

2.1.1. Sustainability Governance System

The sustainability governance system is typically seen as driving corporate behaviour to integrate and address sustainability in business actions [33,40,41]. It is conceived as the arrangements made in order to achieve CS performance [33]. This includes how sustainability is integrated into the strategy and structure, organisational arrangements and implementation processes for achieving sustainability. While a range of studies have highlighted the importance of the sustainability governance system (e.g., [40,44]) and how it is a pre-condition for CS performance (e.g., [33,41]), the question remains for how these governance systems are established within companies.

Building from previous studies across CS and CSA literatures such as [33,40,41], two key elements are identified, underlying the governance systems for sustainability: (1) companies’ commitment to sustainability standards and guidelines (e.g., [38,40,45]) and (2) sustainability structures, leadership and strategy (e.g., [33,40,46]). Embedded into the governance system, companies’ commitment to sustainability standards and guidelines direct the development of sustainability principles, goals and issues that are considered by companies [31,40,47,48]. Both international and country-specific guidelines such as the Global Reporting Initiative reporting framework [40] and national regulations such as across Asia [1] have had a significant role in not only informing corporate practices but also a range of sustainability indicators that direct sustainability implementation. In addition, it is also evident that some specific industry guidelines, such as the Sustainable Manufacturing Initiative, inform how companies select sustainability issue categories to be addressed and measure across their operations [47].

While various sustainability commitments drive companies’ policies and procedures in addressing sustainability, it is the organisational structure including the leadership and strategy that are directing the process including the development of the sustainability strategy [40]. It has been suggested that establishment of a dedicated committee to sustainability across various management levels is essential to achieve better performance of CS as the committee plays a role as a key driver not only in planning the CS initiatives but also in the implementation and reporting. Having a dedicated team would enable the translation of the company’s commitment to sustainability into a broader sustainability strategy, including sustainability goals, addressed issues and range of indicators.

The critical role of a sustainability governance system is seen as a pre-condition for higher standards of CS activities and is evident through various empirical studies. This has been illustrated across the manufacturing sector [47], automotive industry [49] and the financial sector [48]. Despite insights into various sectors, no specific studies to our knowledge have sought to illustrate how various sustainability standards and guidelines have impacted companies’ sustainability activities in the ICT industry.

2.1.2. Measurement of Sustainability Performance

CS performance is acknowledged as a way to demonstrate to what extent companies integrate economic profit, environmental and social responsibilities as well as stakeholders’ consideration into business activities [35]. It provides evidence whether the pursuit of sustainability initiatives derived from the broader sustainability strategies and commitments of the company contribute to either positive or negative impacts on stakeholders [26]. It is also used as a necessary guide for improving CS activities and impacts [50]. While a range of different authors (e.g., [33,51]) suggest the measurement of CS performance as the first basis from which to integrate CS management practices, we rather see it as an independent component within the broader CSA.

It is worth noting that along with the growing research interest in measurement of sustainability performance, studies can be classified into two major clusters based on the scope of the performance measurement: aggregate measures (e.g., [50,52,53]) and individual company measures (e.g., [42,43,48]). Considering the aim of this paper, insights can be drawn more from studies emphasising the measurement of sustainability performance at the individual company level. These studies not only inform what indicators can be used to measure sustainability, but also how measurement systems support the management practices within companies. It is evident that the measurement system aligns more clearly with the broader intent of informing management in how their business operations may contribute to achieving sustainable development.

Measurement of sustainability performance at the individual company level is heavily linked to a set of indicators utilised to monitor and report the performance. Furthermore, these indicators can be used to “identify the goals that lead to the creation of value for the company” [54] (p. 10). Previous research by [55] (p. 240) details the importance of these sustainability performance indicators underpinning a measurement system built from “a system of indicators that provides a corporation with information needed to help in the short and long-term management, controlling, planning, and performance of the economic, environmental, and social activities undertaken by the corporation”. Empirical studies identified providing insights into how companies select sets of indicators to measure their sustainability performance is evident across a range of contexts. This includes indicators adopted by Canadian companies [42], the Indian financial sector [48], mining companies in Ghana [56] and an Australian mining company [57]. While there is no shortage of studies across different sectors, it remains an area where no empirical studies have elaborated on the practices of the ICT industry.

2.1.3. Sustainability Reporting

While it is evident that companies adopt various sets of indicators to measure their sustainability performance, it appears critical to link the indicators with the reporting scenario that companies may have to adopt [58,59]. Reporting is commonly perceived as the final outcome for CS as well as a key communication tool [25,43]. However, extant literature including [58,60] has also demonstrated that reporting actually has a much broader role in driving how sustainability is integrated at the corporate level. It has been identified as a management method to enable companies to report their initiatives in contributing to SDGs, reflected through their economic, environmental, social and governance performance [25]. By committing to the disclosure of sustainability performance through sustainability reporting, companies provide internal and external stakeholders with a clearer picture of the companies’ principles, governance and management values in dealing with sustainability issues [58,61]. In fact, sustainability reporting has a broader influence as it requires a systematic process to be adopted by companies when integrating sustainability management practices into business activities.

Despite the potential role of reporting within the broader CSA, previous studies have highlighted that producing a sustainability report is still quite a challenge for companies and confusing for practitioners [40,58,62]. While previous studies have indicated that the reporting process is directly influenced by the management process-related aspects required to produce the report [45,60,63], there is still paucity of research demonstrating how reporting plays a role in an integrative process of CSA, and specifically, that reporting activity is strongly linked with the governance system and the measurement of sustainability performance. In addition, more empirical studies are needed to demonstrate the ability of sustainability reporting to perform a role as a decision-making tool for articulating the broader company strategies that integrate sustainability and presents the performance of initiatives undertaken by companies, as well as how it can be used to improve sustainability performance [58].

Within this context, further research is needed to demonstrate connections within the broader CSA and across the three different aspects detailed here, as well as pointing to the need to identify how this threads through a comprehensive management process being implemented. While a range of research has been dedicated to respectively examine the sustainability governance system, measurement for sustainability performance and sustainability reporting, to our knowledge, no study has yet fully engaged with the role of each concept within broader CSA processes. So, while these aspects of the CSA have been extensively theorised and individually examined, there remains a distinct need for empirical research to explore this as a full process and to demonstrate the interconnections between these different aspects. This study does exactly this, within the context of an under-researched, yet very important, sector that has been identified as driving proactive sustainability initiatives.

3. Methodology

To shed light on the processes that frame the CS practices of an MNE in a developing country context, this article adopts a single-case study method focusing on the CSA process implemented at Digi. A qualitive case study approach is utilised as it allows “for an in-depth exploration of intricate phenomena with some specific context” [64] (p. 1) and has been acknowledged as the most effective approach for addressing the “how” research question rather than “why” [64]. A single case study is considered as a suitable strategy for an in-depth examination of CS practices adopted by exemplar companies, with previous examples in Asia including Lenovo in China [65], BMW in Korea [66] and Hyundai Motor Company in Korea [67]. These studies support the utility of adopting a single-case study approach for investigating the specific details on how companies undertake actions to address sustainability within their business operations as well as examining the nexus between CS initiatives within multinational companies and sustainable development in Asia.

This study utilises primary and secondary data to examine the sustainability practices adopted at Digi. The data collection approach is informed by previous study including [65,66,67,68]. In order to collect the primary data, this study specifically follows the approach of [65,68] who demonstrate that sufficient primary data can be obtained through a range of meetings and interviews with company personnel, especially through sustainability-related key personnel, for example with a CSR manager [63] or other corporate responsibility team members [68]. In addition, this study utilised a similar approach adopted in [67], with the collection of primary data during a conference presentation of sustainability-related practitioners from the company.

In addition to primary data collection, this study analyses secondary data, collecting and analysing the sustainability reports disclosed both by Digi and the Telenor Group from 2015 to 2019. Previous studies (e.g., [65,66,67]) demonstrate that documenting and analysing corporate disclosures for sustainability allows the capture of companies’ effort and progress in incorporating sustainability practices into business activities. For example, [66] recognised how secondary data had enabled them to have “documented the experience of BMW’s efforts in revolutionizing sustainable mobility in Korea through the BMW i-story”.

Data collection and analysis adopted for this study will be further elaborated in the next section. Primary data for this research was collected from a series of semi-structured in-depth interviews with the Head of Sustainability at Digi, who also coordinated data collection from key people in charge of sustainability-related functions within Digi including the Head of Supply Chain Sustainability, Head of Compliance and Labor Law, Head of Employee Experience, Head of Communications and staff from the HSE team. Additional primary data were also collected through a Digi presentation at the International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA) conference in 2018. Secondary data were collected from publicly available company documents, including Digi Sustainability Report (2014 to 2019); Digi Annual Report (2014 to 2019), Telenor Sustainability Report (2016 to 2018) as well as Telenor Global Impact Report (2016).

3.1. Data Collection and Analysis

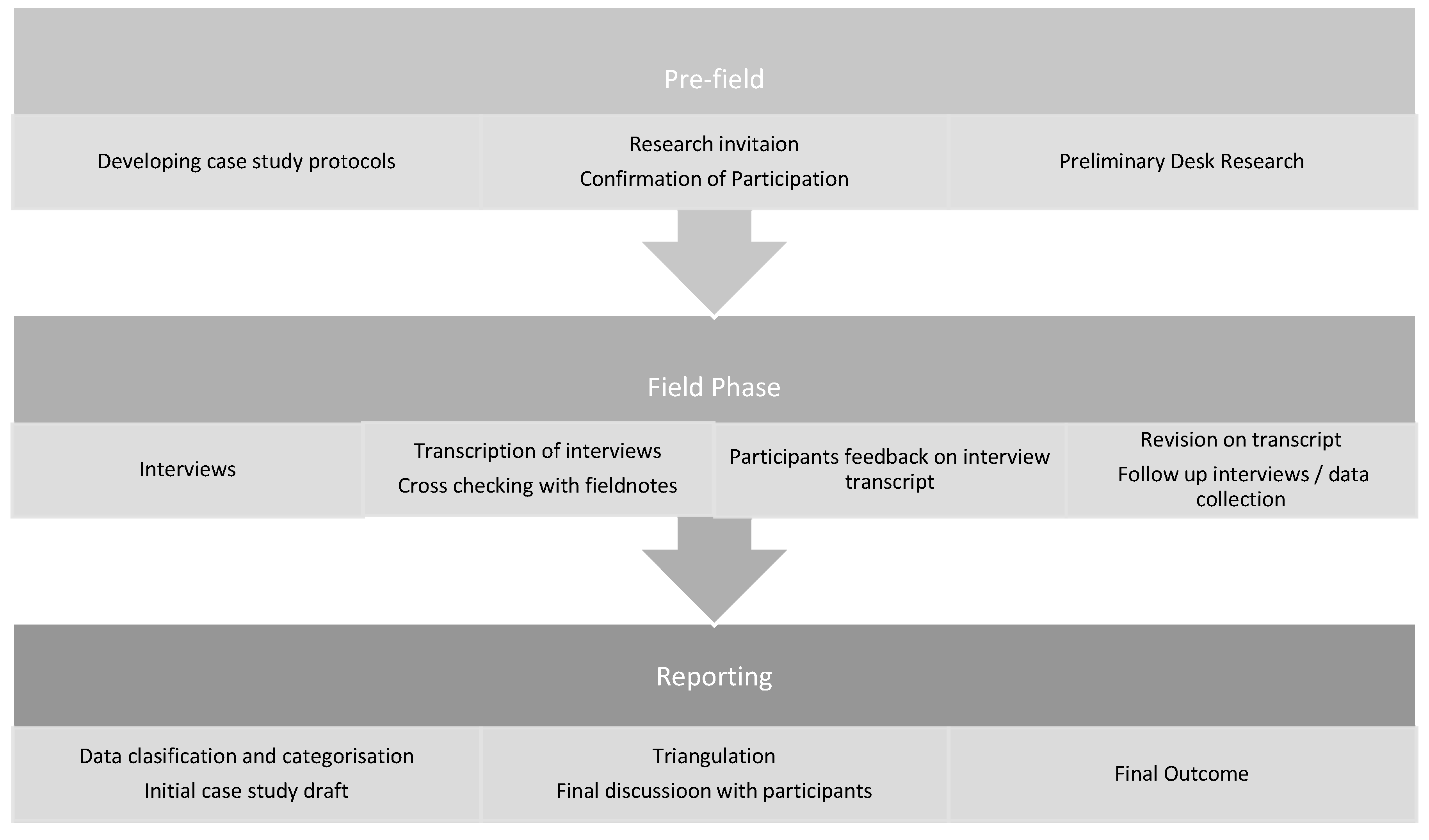

While a case study is commonly preferred, especially when the researcher has little control over the event and when the focus is on contemporary phenomena within some real-life context, adopting systematic steps in data collection and analysis has been recommended to ensure the rigor of the research [69]. In doing so, this study adopted several operational steps suggested by [68] including (1) pre-field phase, (2) field phase and (3) reporting phase (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Data collection and analysis process.

Looking first at the pre-field phase where the case study protocol is developed and communicated to participants, our protocol is framed by a set of procedures adopted for the data collection process [69]. This includes an invitation of participation, interview guidelines as well as a consent to participate form for each informant involved in this study as part of our ethical considerations. The protocol document was used as a basic tool to communicate the research background and objectives, expected involvement from participants as well as the methodology employed. Participants were informed that this study employed cooperative research processes [70], which acknowledges the value of a co-creation process. This means that participants’ feedback on presented results are expected and they can clarify any interpretation should they feel it necessary.

Following the initial contact, follow up phone calls were made to confirm participation as well as scheduling interviews once participation was confirmed. At this phase, all publicly available company documents were screened and explored as secondary data. Here, the secondary data was carefully organised and sorted with a preliminary analysis frame developed, which was also utilised to refine interview guidelines.

In the field phase where the semi-structured, in-depth interviews were undertaken, the research team reviewed the protocol prior to the interviews taking place to ensure that participants were fully aware of the objectives of the study and ethical considerations. Acknowledging that all interviews will be recorded and transcribed, participants had access to all the transcriptions as well as how they would like to be identified. Each of the main interviews took between 35 and 45 minutes and were through both face-to-face interviews in Malaysia and via Skype. Interviews were transcribed and hand-written notes were taken by the interviewers.

Several back-to-back email communications were adapted to gather participant feedback on transcription, interpretation and additional data needed. By doing this, participants were able to confirm any information they provided and clarify any anomalies. The various responses from interviews were analysed and cross-checked with secondary data, with particular attention paid to the key aspect of CSA processes and how they are implemented at company level. Where there were any differences found between interviews and secondary data, follow-up interviews were conducted for clarification. Having said this, major analysis was conducted simultaneously during the data collection periods, which allowed the researchers to have quick follow-ups when more specific data was required.

Data was categorised into three key aspects of the CSA for the reporting phase. This resulted in an initial case study draft of the CSA adopted in Digi. In this phase, triangulation was employed, involving most recent available secondary data, email correspondence as well as field notes taken by interviewers. Emphasising the value of co-creation process adopted for this study, all analysis including a draft of this manuscript, was subsequently sent back to participants for feedback and further input. This enabled the participants to verify the interpretation of analysis and the construction of analysis resulting from the CSA adopted in their company.

3.2. Case Study Context

Digi is a Malaysian listed company that is part of global multinational, Telenor Group, headquartered in Norway. It is a mobile connectivity and internet services provider operating in Malaysia with a stated ambition to become Malaysians’ choice of digital life partner and enable all Malaysians’ digital lifestyle. In fact, Digi was recently awarded as the number one telecommunication brand by Malaysians [71] with a total customer base of 11.7 million people. It has been also recognised as Malaysia’s largest network for its LTE coverage and fibre network, with RM6.436 billion in total revenue [71] and USD$363 million for their after-tax profit [72]. In the region, Digi was recorded among the 50 largest companies by market capitalisation in five ASEAN countries—Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand.

The company’s commitment to sustainability was distinctly reflected through their core business strategy for including responsible business, to “position Digi as an exemplary corporate citizen” [71]. The company believes in the ability of digital communication to empower human beings to improve their lives, build societies and secure a better future, which sets an underlying basis of the company’s CS strategy. Aligning with the company’s core business, Digi responds positively to the international call for private sector’s support in achieving the SDGs. For example, Digi is committed to prioritise and deliver on the SDG 10—Reduced Inequalities.

The company also aspires to empower society and reduce inequalities in the country by providing “access to meaningful internet services for all Malaysians and drive greater socio-economic development for communities”. A range of other commitments to international sustainability standards was also identified, including to GRI Standards where they are recognised as the only Malaysian company to attain the Best Corporate Governance for the highest level of disclosures [73]. Section 4 and Section 5 will elaborate more on how Digi is operationalising the three aspects of CSA including their sustainability governance system, measurement of sustainability performance and sustainability reporting.

4. Results

Utilising three key aspects of CSA detailed above, this case study elaborates upon the iterative procedures adopted by Digi in CS practices into their business activities. This includes how Digi, as a subsidiary organisation operating in a developing country within the Asia Pacific, contextualises a global strategy established through the headquarters level operations in Norway. Analysis in this case study will be presented through the three aspects as a process framework for CSA: (1) Sustainability Governance System; (2) Measurement of Sustainability Performance; and (3) Sustainability Reporting.

4.1. Digi’s Sustainability Governance System

Here, we look first at the sustainability governance system implemented at Digi, which drives the company to incorporate sustainability practices across their business operations. This sheds light on the nexus between the global group’s sustainability strategy and its implementation within local operations. It is evident that the Digi’s sustainability governance system is framed around both Telenor Group’s global commitments to sustainability standards, as well as Digi’s local commitments. It is these commitments that informs the establishment of sustainability strategy, policies and goals across the global and local operations. While the identification of the sustainability principles and values is influenced by the global commitment determined by the Telenor Group, it is Digi’s local sustainability committee that are tasked with translating this into actions implemented at the local level, including identification and refinement of sustainability issues to be addressed through sustainability initiatives.

An examination on Digi’s and Telenor Group’s sustainability reports indicates a strong influence from the parent organisation in informing the actions practiced through the local operations. Looking first into commitments made at global level, it is clearly stated in Telenor’s sustainability report since 2016 that the group is fully committed to supporting the Sustainable Development Goals by the United Nations, with a specific focus on SDG 10—Reducing Inequalities. This commitment links with the Group’s strategic direction for sustainability that has put in place responsible business and empowering societies as its main focus. As stated by the Group’s CEO:

“To us, it’s more than good business. It’s empowering societies. Sustainability at Telenor is about how we do business. We are committed to all UN Sustainable Development Goals but with specific focus on goal #10 Reduced Inequalities. We want to help unlock the benefits of the digital revolution and demonstrate how more can be achieved with connectivity” [72].

Reflected through various sustainability related documents available for public consumption, it appears clear that the Telenor group aims to adopt a responsible business model across all business units, irrespective of the different country contexts. Responsible business spans the areas of human rights, anti-corruption, privacy and data security, supply chain sustainability, environment, health, labor rights, as well as “contribution to societies” [74]. This includes addressing business environment risks, seizing the opportunity to generate positive long-term value and meeting stakeholder expectations. In addition, it has been acknowledged that responsible business also means strengthening awareness, accountability and transparency to secure license to operate and ensure ethical and responsible business practices.

A range of multi-faceted sustainability issues are identified at the headquarters level, informed by multi-layered sustainability requirements and guidelines. This varies across the Group’s home country requirements, such as through the Norwegian Government requirement on sustainability, Oslo Stock Exchange Guideline, European Union NRF directive and Norwegian Accounting Act, and a range of international standards for sustainability including the United Nation Global Compact (UNGC), GRI and Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP).

From discussions with the Head of Sustainability of Digi, it is clear that the parent organisation played a significant role in driving the sustainability practices adopted by Digi. This is clearly reflected in how Digi links their commitments to international sustainability standards such as UNGC, CDP and GRI. However, it is worth noting that contextualisation is practiced by Digi in Malaysia. The Head of Sustainability explained that the sustainability approach adopted by Digi is a combined approach of the global perspective driven by Telenor, while the local ambition to be a sustainability leader in Malaysia is also a key consideration in framing their innovative approaches to sustainability. He elaborated that the approach to contextualise sustainability issues addressed in Malaysia is to an extent driven by Malaysian compliance and regulation, as well as other international commitments that they see as being relevant to their context. So, while Digi follows the internal sustainability policies developed by Telenor Group, it has also committed to local requirements and guidelines such as Bursa Malaysia’s sustainability framework and broader best practices through following international standards and certifications such as ISO, OHSAS, LEED, etc.

“We are in regular conversations with the Malaysian regulators on areas relating to compliance and international best standards. Being a public listed company under Bursa Malaysia, we have adopted Bursa’s Sustainability Framework to disclose a narrative statement of our material economic, environmental and social risk and opportunities aligning to the GRI guidelines. Our reporting covers our efforts around the ESG criteria in workplace, marketplace and communities. We are also an exco member actively contributing in the Business Council for Sustainable Development in Malaysia (BCSDM) which is part of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), a global CEO-led organization.”

Looking further into this, it is worth noting that Digi’s endeavour to integrate CS practices into business activities has also been informed by several different sectoral policy or frameworks that address issues across different impact areas.

“The telecommunications industry Malaysia has a strong regulative framework under MCMC which also promotes self-regulation by the industry to work together in new frontiers given the onset of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, Hence, we have regular and ongoing discussions even when it comes to understanding and regulating emerging technologies.”

The mixture between the global, local and sectoral commitments to address sustainability is reflected in Digi’s sustainability framework. This framework aligns to the corporate strategy and ambitions in two focal areas where sustainability is incorporated. First, that it is a responsible business by creating long-term trust and shared value across business operations, and second, that it is focused on reducing inequalities by extending the benefits of mobile and digital communications to enable digital inclusion and build digital resilience in communities. This framework is helmed through the Ethics and Sustainability Forum that is also responsible to monitor and report performance outcomes.

Digi’s Ethics and Sustainability Forum is a steering committee chaired by the Chief Executive Officer and comprised of senior management including the Chief Human Resource Officer, Chief Technology Officer, Chief Corporate Affairs Officer and the Head of Legal. The working committee includes the Sustainability Department, Supply Chain Sustainability Department and the Compliance and Labor Law department. These departments manage the day-to-day practices and work closely with other departments with functions related to sustainability (e.g., Privacy Officer, HR, HSE, Network waste, etc.) and reports regularly to the steering committee responsible for Digi’s sustainability governance. It is the Ethics and Sustainability Forum that is responsible for formulating the sustainability strategy, policies and goals; decision making, monitoring and facilitating adherence to the sustainability policies; supporting departments to meet sustainability objectives; conducting sustainability awareness and engagement activities; and reporting the sustainability performance quarterly to Digi’s Management Team as well as to the Board of Directors and the Telenor Group.

From this point, the sustainability framework and the key areas identified are subsequently delineated down into more specific issues and impacts to be addressed within the whole CSA process. The framework leverages a materiality assessment as a strategic platform to integrate material issues when incorporating sustainability into business strategies and operation. A recent study called this as the “issue identification and refinement process” [38].

Looking more closely into the role of a sustainability-dedicated team at Digi, the local operation not only prioritises but also contextualises the identified issues through a materiality assessment process. The company’s Head of Sustainability acknowledged that the materiality assessment adopted at Digi was built upon the materiality assessment undertaken at the Group level, which was then contextualised for the local operations. In doing so, Digi adopted the GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards in informing their materiality assessment, which informed how the company adopted a participatory approach to comprehensively engaging with their internal and external stakeholders.

“Leveraging on the materiality assessment from Telenor, we would localise it through our stakeholder engagement process. …. We conduct stakeholder engagements with key representatives from the government, investors and analysts, regulator, with regulators, with key partners, suppliers, media, relevant NGOs, and with key account customers. So through a comprehensive stakeholder engagement finding, we would regroup with the Ethics and Sustainability Forum and Management to finalize the materiality matrix for our organization. We conduct an extensive materiality assessment process every few years and in between, we would use an internal review with management to ensure relevance.”

When examining this process, it starts from the material issues that were established by the Telenor Group’s materiality assessment. A range of significant issues across social, economic and environmental aspects were then re-identified in accordance with their significant level for stakeholders and company. The issues were then delineated across the level of importance for both external stakeholders and the company. They were scaled across nine boxes, each detailing a different level of importance from low, medium, to high importance. Emphasising the mapping process, the Head of Sustainability at Digi explained:

“The process is usually triggered by the Sustainability department which will engage all other functional departments with scopes relating to ESG, value chain and key stakeholders. We will also engage an independent third party when it comes to executing anonymous surveys with some stakeholders to ensure impartiality.”

Several different platforms were established to engage with stakeholders in this process. For example, to engage with regulators, Digi provided regular reports and conducted information sharing with the relevant ministries, in addition to the public-private partnership initiatives that are undertaken. Some issues were identified through this engagement platform such as accessibility of internet, quality of connectivity and the National Digital Innovation Agenda. Another example is through engaging with business partners, with several issues identified in the supply chain through platforms such as the annual self-assessment questionnaire distributed to suppliers, site inspection and audits, and supplier training. The identified issues included health and safety within the supply chain, non-compliance issues within the supply chain, as well as integrity due diligence. Furthermore, to engage with communities, Digi has established a partnership with UNICEF, along with partnering with government agencies, other corporates and NGO forums. Some issues emerging from this engagement include leveraging mobile technology to empower local communities and safe internet use by children.

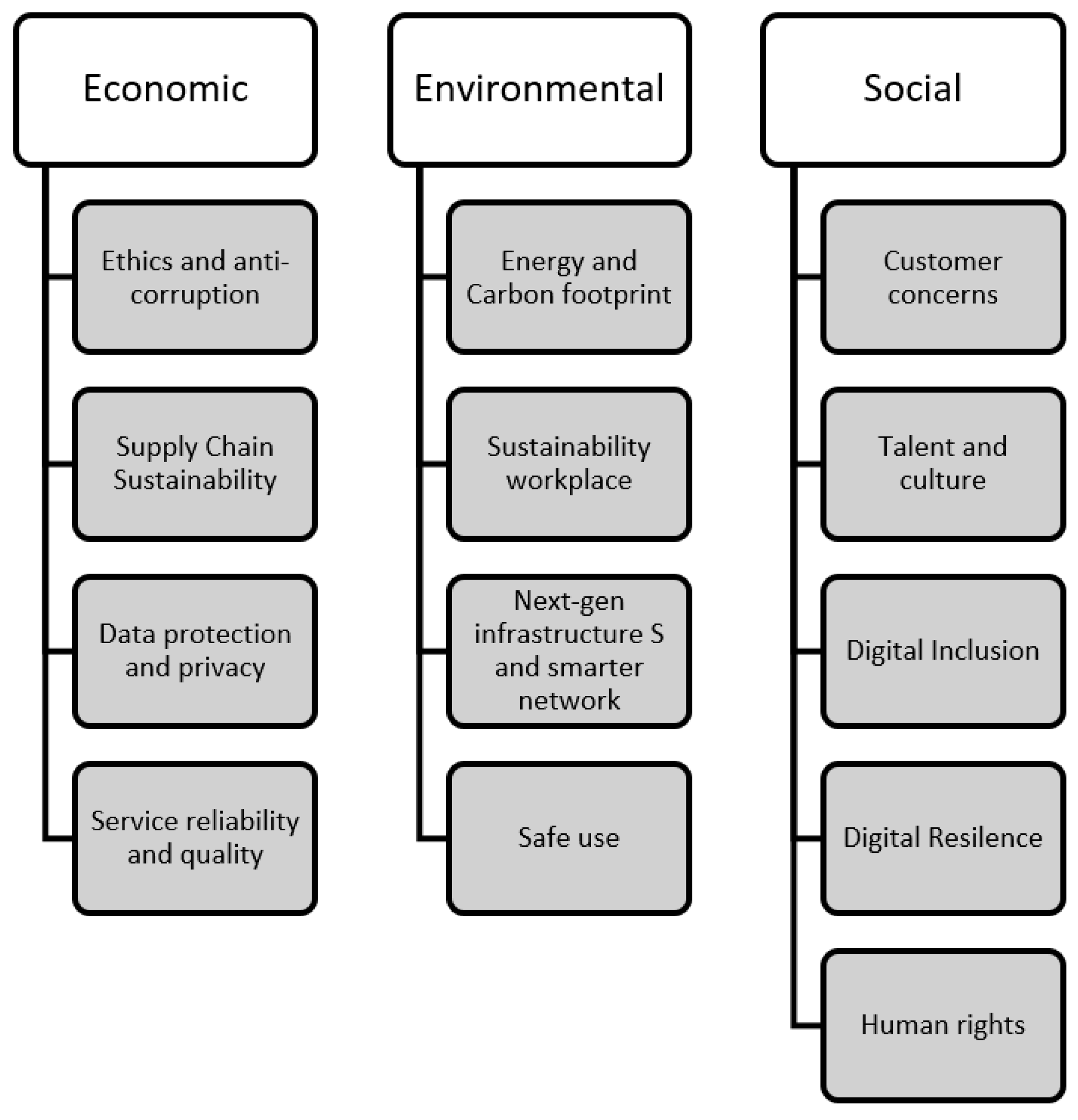

By doing so, the company was able to maintain coherence in their prioritised issues and impacts with current expectations from their stakeholders within the local context. The consistent approach to stakeholder engagement allowed the company to make necessary adjustments to anticipate changes in the market and expectations of their stakeholders. Recently in 2018, Digi refreshed their materiality matrix as the company upgraded their commitment to sustainability from GRI G4 to using selected GRI standards. This resulted in the identification of issues that were disclosed in the Digi Sustainability Report 2018. The disclosure is in accordance with internal policies, Telenor Group’s Non-Financial Reporting Procedure and Digi’s Standard Operating Policy and Procedures on Sustainability Reporting, as well as more broadly linked with their commitment to various international standards such as GRI, UNGC and CDP. Below, Figure 2 illustrates the key sustainability areas and issues for Digi across the three dimensions of sustainability.

Figure 2.

Digi’s key sustainability area and issues identified (modified from Digi input).

4.2. Measurement of Sustainability Performance at Digi

It is important to determine the potential and/or actual impact of sustainability initiatives undertaken by a company. By measuring sustainability performance, to what extent businesses integrate economic profit, environmental and social responsibility as well as stakeholders’ consideration into business activities can be captured [35]. This section will elaborate on the actual process adopted in a company to determine the impacts of their initiative, starting from translating the identified issues into a more measurable basis. It is subsequently followed by collecting data on actual performance and might involve the establishment of baseline data and methods for ongoing analysis. It is common to use surveys or scoring systems, quantitative modelling and quantitative methods to track the performance at this point. Qualitative approaches are also expected to be adopted to determine performance. In order to inform the type and depth of potential/actual impact of the undertaken sustainability activities, international commitments and sustainability standards are typically considered.

Similar to the establishment of a sustainability governance system, the examination of sustainability reports at both Digi and Telenor Group indicates a strong influence through the Group’s commitment to international standards to inform the impact analysis practices adopted at the local operational level. At the global level, the Telenor Group adopts several standards to measure and communicate their environmental, economic and social impacts that underpin their non-financial reporting standards. Telenor aligns their impact disclosures in accordance with GRI standards’ Core option. While each of GRI standards’ indicators are cross referenced with the 10 Principles of the UNGC and linked with the 17 SDGs by the United Nations, Telenor also combined their Group Sustainability Report 2017 as part of their Communication of Progress (COP). The COP is reflected in their commitment to support the international agenda in achieving the SDGs.

In addition to this, Telenor also committed to several different guidelines for specific sustainability areas. For example, in relation to its environmental impacts, Telenor adopted CDP standards that direct the commitment of the Group’s different business entities across the global operations under the Group’s Environmental Management System (EMS) in line with ISO14001. A reporting platform called Synergi Life, a risk management software that was developed by DNV GL, is utilised to enable all business units to report their performance across environmental, health and safety issues. The Synergi Life also allows business units across the Group’s operations to manage non-conformity, incidents, risk, risk analysis, audits, assessments and improvement suggestions. In Malaysia, the Synergi Life has been utilised to specifically focus on analysing impact related to supply chain issues.

Looking more closely to the practices adopted by Digi in Malaysia, the Head of Sustainability revealed that in order to measure the performance across several different issues, Digi has been utilising a Non-Financial Reporting (NFR) tool.

“In our reporting system, we have also adopted a non-financial reporting (NFR) tool. Using Oracle’s Hyperion system for our NFR, it allows us to capture data relating to environmental impact and we combine this with our internal processes to capture other relevant data such as compliance and training hours. We also conduct a human rights due diligence every two years.”

Similar to the Synergi Life that was developed at a global level, the NFR tool is used by all business units of Telenor globally. As part of the Group’s sustainability commitment, the NFR tool is linked to the Group’s commitment to GRI, in terms of the data that is needed for the international sustainability standard they are adopted. Given the fact that the NFR tool was developed to meet global expectations, it was set to automatically cover impact areas and issues prioritised in the local context of Malaysia. In relation to people development, Digi leverages on learning platforms such as Lynda, Coursera and Audacity (a nanodegree platform) to track learning hours by employees.

It seems to be clear that quantitative modelling and quantitative methods to track the performance are being adopted maximising the use of digital platforms. Here, the data is linked with different indicators that the company need to focus on. In addition, this data was utilised to undertake external assurance processes as part of the company commitment to provide credible reporting. As explained by the Head of Sustainability:

“Having these various digital platforms and tools, it makes for a more structured approach for us when it comes to conducting audits and external assurance processes. Data will be extracted from the various systems and compiled into an assurance process mirroring the GRI standards.”

Looking more closely to how Digi is measuring their performance in specific issues or impact areas, some specific tools and standards are commonly utilised. Looking first at environmental impact areas, while Digi adopts some international standards to measure their environmental impact such as CDP, it is worth noting that Digi Malaysia has upgraded their EMS to ISO 14001:2015 and has undertaken LEED certification and Green Building Index certification for their buildings and data center. It is a proactive initiative by Digi that is aimed at allowing it to be a step ahead with other business units in Telenor. This allows Digi to adopt international practices into their day-to-day operations to minimise environmental impact and reduce wastage of resources.

From an operational perspective, more specific issue categories are then delineated, aligning with the Group’s commitment. Each issue category is then broken down into specific indicators to be analysed by the company. For example, there are four issue categories that have been delineated down from climate and environment issues. This includes energy efficiency, sustainable workplace, infrastructure and waste management. To analyse the energy efficiency itself, indicators have been put in place, such as energy consumption, energy intensity and carbon emissions. Aligning to the GHG protocol, Net Carbon emission, for example, is then broken down further to include the overall different type of carbon emissions and presented as the total carbon emissions per year, as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Illustration of emissions by scope.

The process allows Digi to analyse their environmental impact and identify what could be done to improve the outcome. By breaking down the carbon emissions into three scopes as identified under the GHG protocol, the company has been able to identify where the main sources of their carbon emissions are in order to implement mitigation strategies. As per reported in 2018, Digi’s largest carbon emission is from Scope 2–purchased electricity from grid. A set of strategies was then developed and implemented to reduce the emission from this item. Through this process, the company is able to compare year-to-year the impact of the mitigation strategies as seen in their initiative to reduce flights, which had in turn achieved carbon savings in scope 3.

Moving from environment and climate change issues, another example can be drawn from the human rights area. As part of their global commitment to respect human rights, Telenor committed to follow the United Nations Guiding Principle on Business and Human Rights, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprise, and, in general, to the UN Bill of Human Rights. In addition to these, a global partnership with UNICEF was established to specifically address children’s rights. This commitment has been made at global level as part of the Telenor endeavour to address child labor issues.

Following the direction put in place at the global level, a partnership with UNICEF was also established at Digi Malaysia to address children’s rights issues. In 2017, Digi completed the UNICEF Mobile Operator Child Right Self-Impact Assessment Tool (MO-CRIA), which was developed together with GSMA and is designed to strengthen corporate practices in relation to children’s rights. The MO-CRIA itself is a tool that provides a framework to assess business impacts, associated impacts and identify gaps as well as opportunities to create better business sustainability outcomes when it comes to children’s rights. In a discussion with the Head of Sustainability, it is further revealed:

“In 2012, Digi alongside UNGC Malaysia committed to the Children’s Rights and Business Principles developed by UNICEF to strengthen our commitments towards building a more stable and sustainable future for the next generation. We are glad to reach a milestone towards this commitment in 2017 when we became the first telecommunications company in the world to implement the comprehensive MO-CRIA assessment to ensure we have child-friendly policies and good governance around children rights, especially in the digital world.”

While it seems to be clear that the Group’s commitment plays a significant role in sustainability practices adopted by Digi, some proactive initiatives have emerged from local operations that allow the distinct contextualisation of sustainability to fit with the Malaysian context.

4.3. Sustainability Reporting

From examination of the sustainability reporting activities adopted at Digi, it seems clear that the process involved not only captures the performance data but also evaluates performance. By doing so, the on-going sustainability impacts and outcomes of implemented initiatives can be determined. While at the same time, it can be examined whether the performance of the chosen activities meets the expected outcomes or aligns with the sustainability goals identified within the sustainability governance system.

Again, a nexus is evident between the global corporation and local operations. From the global perspective, reporting activities can be extracted from the Group’s sustainability reports and related sustainability documentation available on their website. As has been mentioned within the measurement for performance aspect, the Group utilised Synergi Life as a reporting platform that allows the different business units to report their sustainability performance across environmental, safety and health issues. Another example is through the Telenor Group carrying out local inspections in all their markets to monitor compliance with the requirements in the Group’s responsible business conduct. It is reported that about 5000 supplier inspections, ranging from simple visits to full audits, were carried out by the Group in 2017 across their global network of operations.

Gleaned from the Group’s and Digi’s sustainability reports as well as sustainability-related publications, sustainability governance and key performance indicators (KPIs) have a significant role in monitoring and evaluating sustainability performance across the global business. It is the Telenor Group Sustainability that sets KPIs for all business units across the Group. Quarterly reporting by the business units to the Telenor Group Sustainability is required. At the local level, the quarterly reporting to the Group is managed by Digi’s Ethics and Sustainability Forum. The reporting is based on on-going day-to-day processes undertaken within sustainability department. This daily operation within the sustainability department is overseen by the Head of Sustainability.

Looking more closely into how the sustainability performance is being captured, quantitative and technical approaches are evident. The Head of Sustainability explained that data is typically collected in excel, designed to meet indicators required by some best-practice sustainability standards such as the GRI. The data collection process to track indicators varies from monthly to quarterly to support the quarterly reports required by the Group.

“Some data are collected on a monthly basis while others are collected quarterly. Review meetings are setup quarterly but a major review is done annually when we go through the entire data. This is followed with presentations to Management and Board and includes data reporting, mitigation and improvement plans.”

A more specific example of how Digi undertakes their reporting practices can be drawn from how the company is addressing supply chain issues. Focus has been specifically put in place in addressing this issue as part of the global sustainability strategy and commitment to adopt best practices and minimise negative impact across all the business operation. The Head of Sustainability elaborated this comprehensively in a discussion session:

“Our commitment to responsible, fair and safe workplace extends to the over 75,000 individuals estimated to be working in our supply chain. This is aligned to our pledge to reduce inequalities by raising standards and building capacity for our supply chain. All our suppliers are required to sign an Agreement on Responsible Business Conduct (ABC), committing to embrace ethical conduct, best practices in Health, Safety and Environmental responsibility. We have been certified OHSAS 18001-2007 and recorded zero lost time injury frequency (LTIF) in 2017. In line with our continuous effort to ensure the health and safety of employees, we introduced a dedicated hotline number, 29588, for emergency incidences such as fire or health related cases with immediate assistance by trained individuals before emergency medical personnel are available on site. 35 employees have been certified as First Aider volunteers.”

“We have also created a mobile application (D’PTW) where our contractors, sub-contractors, suppliers, and vendors can now easily manage projects and get quick approvals via the D’PTW app. So, based on submission of approvals on the app, contractors have to report on the readiness of each planned visit (i.e., how many workers on site, how many harnesses, fire extinguishers) and when we do our inspections, we would validate that what is reported in the approval is actually implemented on site.”

The quarterly reporting has been utilised to inform the on-going performance and evaluate the performance, as well as a final level of reporting activities. Both from the global and local perspectives, the importance of credible reporting with transparent and valid data is highlighted. This is indicated through undertaking limited assurance by an external auditing firm. The selected indicators include carbon emissions, energy consumption and signed agreement of business conduct in the supply chain.

While the annual report is typically perceived as the final level of reporting, an examination of the actual practices adopted at Digi shows a feedback and follow up process that is focused on making continuous improvements/adjustments as a result of the examination of performance. This includes reassessing existing strategies that have been implemented to address refined issues and changes in focal points or material issues that are incorporated into materiality assessment activities and operational practices. This is also considered as an opportunity for learning to occur in how the broader CSA activities are being undertaken. A great example to illustrate these practices can be illustrated in Digi’s initiatives on child rights and online safety. The process was explained by the Head of Sustainability of Digi:

“Since 2011, Digi has supported the Convention of the Rights of Child (CRC) in the area of protecting children. Digi believes that the internet should be a safe space for children and they should be protected against online violence and exploitation. After executing various programmes on capacity building and awareness, Digi decided to follow up with national surveys to understand the impact of these programmes towards behavioural change and safer online practices by these children. Using the feedback and findings of the survey, it has allowed us to further improve our programmes to be relevant to the needs and concerns of the young people. One year ago, to further improve our best practices, we undertook the UNICEF Mobile Operators Child Rights Self Impact Assessment(MO-CRIA) to ensure that the entire organisation and all aspects of business is align to ensuring none of our services undermine or exploit the rights of children. Digi was the first operator in the world to undertake the MO-CRIA exercise.”

Within ethics and compliance, another example can be drawn from consumer responsibility. While Digi is aiming to become the preferred digital provider in Malaysia and connect customers to what matters most to them, the company is committed to comply with the Communication and Multimedia Consumer Forum Code of Conduct and the Internet Access Code. These compliance mechanisms emphasise the importance of safeguarding privacy. This means ensuring all data collected from consumers are processed according to the stated and relevant purpose in which it has been collected. In order to enhance privacy outcomes for consumers, various strategies have been adopted. One of them is by strengthening the processes within Digi, which includes assessing privacy notices, aligning data handling procedures and operating systems with national regulations such as the Personal Data Protection Act 2010 and the company’s internal Privacy Policy. Several training and awareness activities are also conducted for employees who deal with personal data on a daily basis in the contact center and retail stores. This aims to create awareness for employees on the importance of protecting consumer privacy.

Another example to illustrate existing strategies that have been implemented are reassessed to address refined issues can be drawn from how the company sets a mitigation plan for its ethical business practices. As part of Digi’s commitment to being ethical and compliant in their business operations, the company conducted ethics and compliance risk assessment company-wide. This exercise allowed the company to identify possible risks and proposed mitigation plans to address these. Examples of mitigation strategies can be drawn from Digi’s efforts to improve their performance in supply chain sustainability issues. In order to ensure business partners were aligning their practices with Digi’s code of conduct and sustainability practices, strict policies that may result in partnership suspension has been applied:

“Upholding high standards of corporate ethics is key to long-term value creation and contributes directly to improved business performance. And we have sharpened our strategy to further emphasize the need to maintain a culture that safeguards the responsible and sustainable business practices we are known for, built on a solid foundation of strong moral values and a deep sense of integrity. This is maintained by establishing a business environment with partners who share our commitment to high standards of ethics and integrity, and ensuring the right principles of anti-corruption, customer privacy, consumer responsibility, supply chain sustainability, and safe use of equipment are upheld across our business. Non-compliance of these standards will result in suspensions and terminations. We remain committed to continuously meeting and setting the standard of excellence in this area within the industry.”

Other than addressing ethical business practices, a great example can be drawn from how the company tries to minimise their energy consumption. This process is inherently linked with the impact measurement they adopted. Following the Group’s direction in tracking down their energy usage and carbon emission from the grid and generators for the company’s network, buildings, flights and rental vehicles, allows Digi to be aware of the most significant area that emissions are produced. Some of the initiatives that stem from these impact analyses included renewable energy substitutes for fuel production, energy efficiency through new network, technologies, green building and data centers, carpooling programs and hybrid car investments, digitisation processes for customer bills and HR processes (reduction of paper usage), and logistics management. These various initiatives are put in place to stabilise energy consumption and eliminate waste and inefficiencies.

Furthermore, as part of Digi’s commitment to reduce their carbon emissions, a focus was in place to reduce the energy dependency on diesel. The company has progressively transformed a significant number of their transmission sites located off the national electricity grid (off-grid) to run on electricity instead of using diesel-powered generator sets. Digi also undertook a massive network modernisation process whereby much of the legacy equipment located in its 7000 base stations and towers that require air conditioning were replaced with new technologies that can operate in room temperature environments. In eliminating the cooling requirements, Digi’s energy usage is significantly reduced.

5. Discussion

This study has specifically sought to examine the management processes and practices being adopted to address sustainability by a major multinational company operating in a developing country context within the Asia Pacific. In doing so, this research has sought to address an ongoing issue in explaining how sustainability is addressed by organisations through CSA. That is, connecting the well-established, yet often disconnected, aspects of the CSA through a holistic examination of one exemplar case study.

Beyond this, this study has provided empirical insights into a key industry within developing countries within the Asia Pacific that enables the rapid transformation and connection of these markets to the global marketplace, the ICT industry. With its power to provide the digital infrastructure to these markets, and its assumed proactive engagement of sustainability, this case study provides unique insights into how sustainability is managed in developing countries. Building from this point, the following sections explore the specific contribution and insights to the extant literature across the three conceptual components identified in the literature review on corporate sustainability assessments, beginning with the sustainability governance system.

5.1. Sustainability Governance System: A Nexus between Headquarters and Subsidiary

This case highlights the significant interplay between the home and host country contexts, which illustrates the complexity of how global multinationals approach CSAs. The case conforms with expectations set in the extant literature, including the importance of company commitments to sustainability standards and guidelines (i.e., GRI, UNGC and CDP) and the significant influence in directing the development of the sustainability principles, goals and issues (i.e., [30,39,44]). Yet, it is evident that the subsidiary extends beyond the headquarters commitments, demonstrating significant autonomy and proactiveness in their sustainability approach.

Part of this was clearly driven by a commitment to meeting local regulations [1], such as the Bursa Malaysia, which is the stock exchange of Malaysia, and the sectoral MCMC, but Digi also sought to go beyond this. This included in setting an objective to become a sustainability leader in Malaysia, committing to the Business Council for Sustainable Development in Malaysia and also partnering with different international and local agencies (i.e., UNICEF) to further understand and contextualise their approach to sustainability. It is clear that the broader sustainability commitments set by Telenor are an important aspect of this, but there is clear engagement with the desire to contribute towards sustainable development that goes beyond a central, headquarters-driven approach. This is clearly part of the broader culture that has been set up within the group approach to sustainability.

While sustainability structures, leadership and strategy are often set and driven through the corporate headquarters, this case clearly shows a decentralised approach being adopted. Digi had dedicated committees that reflected a strategic level orientation (with their steering committee) through to an operational level implementation (working committee). The structures in place were supported through a top-down approach (strategy, policies and goals set, then implemented and managed), which cycled back through both committees in regular monitoring and reporting cycles.

As a final aspect of the broader governance system, Digi has a whole set of specific issues and indicators that are aligned with both the requirements set through the headquarters and the contextualisation to meet the local environment. Issue and indicator selection was again an interesting aspect of the interplay between the headquarters and subsidiary operations. At the Group level, a global materiality analysis was undertaken to identify material issues, Digi also adopted a materiality analysis to further contextualise and prioritise issues within the local context. This sees the convergence of two distinct drivers with the international commitment to GRI reporting and the local regulatory requirements through Bursa Malaysia. As a subsidiary, they take the Groups material issues and further contextualise these to identify priority areas within Malaysia.

5.2. Measurement of Sustainability Performance: Sequencing from Governance Systems

An examination of the measurement approach adopted in the case demonstrates again the nexus between headquarters and subsidiary activities, with broader commitments to sustainability standards playing a key role in informing what is measured. This includes a criss-crossing set of interconnected commitments to GRI, UNGC, CDP and ISO, integrated through a reporting platform and non-financial reporting tool to collect the data for these requirements. Other local level platforms have been integrated to track other more specific areas in the operations of the subsidiary.

Perhaps most interestingly was the proactive and sector-specific approach adopted by Digi to reflect the commitments of Telenor to human rights. They partnered with UNICEF to develop an assessment tool for checking on child rights at their sites, including having child-friendly policies and governance aspects to protect the rights of children. What is clear from these activities is that while the headquarters operations are an important driver in the practices being adopted by the subsidiary, there is still flexibility and local adaption to contextualise the approach to measuring sustainability performance to reflect the specific context of Digi.

The examination of the measurement approaches for the sustainability performance clearly show the sequencing and integration with the sustainability governance system. It is evident that the actions undertaken to set the commitments, policies, goals, issues and indicators within the broader governance system sequence to direct what is being measured. While this is largely reflective of previous research (with the potential link with governance systems and measurement), it nevertheless reveals important insights into the actual practices for implementing within a global multinational and the interplay between headquarters and subsidiary operations.

5.3. Sustainability Reporting: Evaluating and Communicating Performance

While previous studies have highlighted that sustainability reporting is in fact a management method to aid sustainability practices [25] and an important communication tool to report sustainability initiatives [51,56], it has not been considered part of traditional conceptions of a CSA. What is clear from this study is that sustainability reporting does in fact have a central role within the CSA It acts as a tool for both the headquarters and subsidiary operations to evaluate their performance in a cyclical manner, identify new strategies to address performance outcomes and communicate with external stakeholders.

The importance both Telenor and Digi place in the use of sustainability reporting for these contexts is reflected not only in the external auditing of these reports, but also the way it is used as a learning tool for reflecting on the sustainability strategies and initiatives, as well as considering performance improvements needed. The localisation approach evident throughout the other aspects of the CSA processes is also evident here with both Telenor and Digi producing separate but interdependent reports.

The examination of this case emphasises the integrative nature of the three different aspects with sustainability reporting considered as an anchor point in a cyclical process. The implications of different management decisions, such as commitments to international standards, is reflected in the approaches to reporting on different sustainability. Likewise, the actual areas being measured and funneled through into the reporting, provide both an evaluative and communication function within the organisations.

5.4. Insights from the Case for Corporate Sustainability Assessments

The case of Digi is particularly insightful when considering the current state of knowledge on corporate sustainability assessments. Empirical investigations providing a holistic view into the management practices across the entire CSA process are limited with a few key studies undertaken by [31,32] that have sought to chart the entire process. This study breaks new ground in not only illuminating the important interplay between headquarters and subsidiary actions in global multinationals, but also the interconnections between each of the key components of the CSA, showing a clear sequence in how managers seeking to address sustainability do so in a holistic manner.

While extant literature has largely adopted narrow focuses on examining different elements of the CSA, this study shows that for managers to effectively address sustainability through their business activities, this needs to be approached from an entire system perspective. How the governance system is established has a fundamental role in directing the performance measurement systems that are implemented and reported upon. Likewise, the performance measurement systems and reporting practices provide critical inputs into a learning organisation adjusting and implementing continuous improvement strategies for addressing sustainability.

6. Conclusions

This research has provided an initial basis for testing a more holistic consideration of the different aspects of the CSA. In doing so, the findings support the three distinct, but interconnected aspects: the sustainability governance system, measurement of sustainability performance and sustainability reporting. This is the first study, to the knowledge of the authors, that has sought to examine all three aspects together and empirically test this. With this context, this study has provided an important contribution towards providing a more holistic view of how companies are seeking to address sustainable development within their operations.

The case also offers a unique examination of the dynamics of a multinational enterprise operating within a developing country within the Asia Pacific. What is clear is that the strong sustainability foundations set in the headquarter operations have influenced and directed the subsidiary, but that this has been localised through a proactive approach adopted by the subsidiary operations. This points to the importance of considering the leadership and culture that is being developed in multinationals, which clearly had a role in creating sustainability as a shared mission across the different business units and operating contexts.. While we hope this study has been insightful, it is, however, limited by the context of the telecommunications industry.

Building from this point, it is recommended that future studies not only consider a more holistic examination of CSAs (including the three concepts detailed here) but extend to other industries. The role of industry-specific actions was often seen to contextualise the sustainability actions of the subsidiary in this case, and it is reasonable to assume that this will be the case across industries. In addition to this, while the focus has been on private sector activities, these practices may also be translated into different contexts such as public sector procurement programs where the private sector is heavily involved in providing services or products, and thus may be a future research opportunity (e.g., [75,76]). Beyond this, while in-depth case studies provide an excellent basis for exploratory studies such as this, future research should consider expanding the size of the sample to capture both differences within industries and across industries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, data collection, investigation, validation, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, A.P.; conceptualization, supervision, visualization, writing—review and editing, J.D.D.; result interpretation, writing—review and editing, C.T. and E.K.M. All authors contributed to writing the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ike, M.; Donovan, J.D.; Topple, C.; Masli, E.K. A holistic perspective on corporate sustainability from a management viewpoint: Evidence from Japanese manufacturing multinational enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 216, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topple, C.; Donovan, J.D.; Masli, E.K.; Borgert, T. Corporate sustainability assessments: MNE engagement with sustainable development and the SDGs. Transnatl. Corp. 2017, 24, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcadell, F.J.; Aracil, E. Can multinational companies foster institutional change and sustainable development in emerging countries? A case study. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2019, 2, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, F.; Faria, L.G.D. Addressing the SDGs in sustainability reports: The relationship with institutional factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Alves, F.; Pace, P.; Mifsud, M.; Brandli, L.; Caeiro, S.; Disterheft, A. Reinvigorating the sustainable development research agenda: The role of the sustainable development goals (SDG). Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2017, 25, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narooz, R.; Child, J. Networking responses to different levels of institutional void: A comparison of internationalizing SMEs in Egypt and the UK. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, F.; Frey, M.; Testa, F.; Appolloni, A. Environmental value chain in green SME networks: The threat of the Abilene paradox. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 85, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zanten, J.A.; Van Tulder, R. Multinational enterprises and the Sustainable Development Goals: An institutional approach to corporate engagement. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2018, 1, 208–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Banks, G.; Hughes, E. The Private Sector and the SDGs: The Need to Move Beyond ‘Business as Usual’. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A.; Van Tulder, R. International business, corporate social responsibility and sustainable development. Int. Bus. Rev. 2010, 19, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Mccord, M.; Kapoor, A. Transforming Business Models in Fast-Emerging Markets-Lessons from India. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2015, 59, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]