Increased (Antibiotic-Resistant) Pathogen Indicator Organism Removal during (Hyper-)Thermophilic Anaerobic Digestion of Concentrated Black Water for Safe Nutrient Recovery

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Analytical Methods

2.3. Statistical Methods

3. Results and Discussion

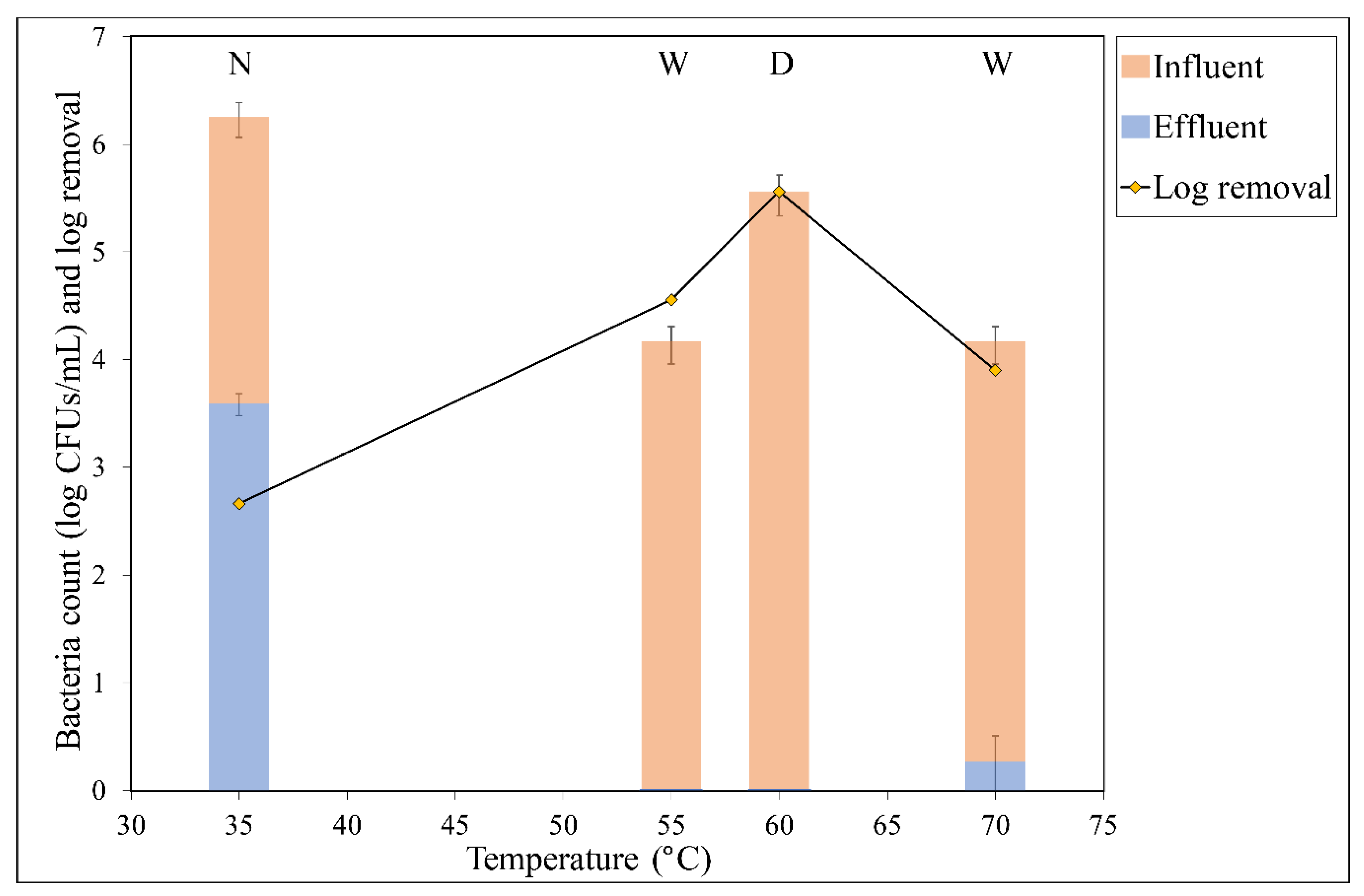

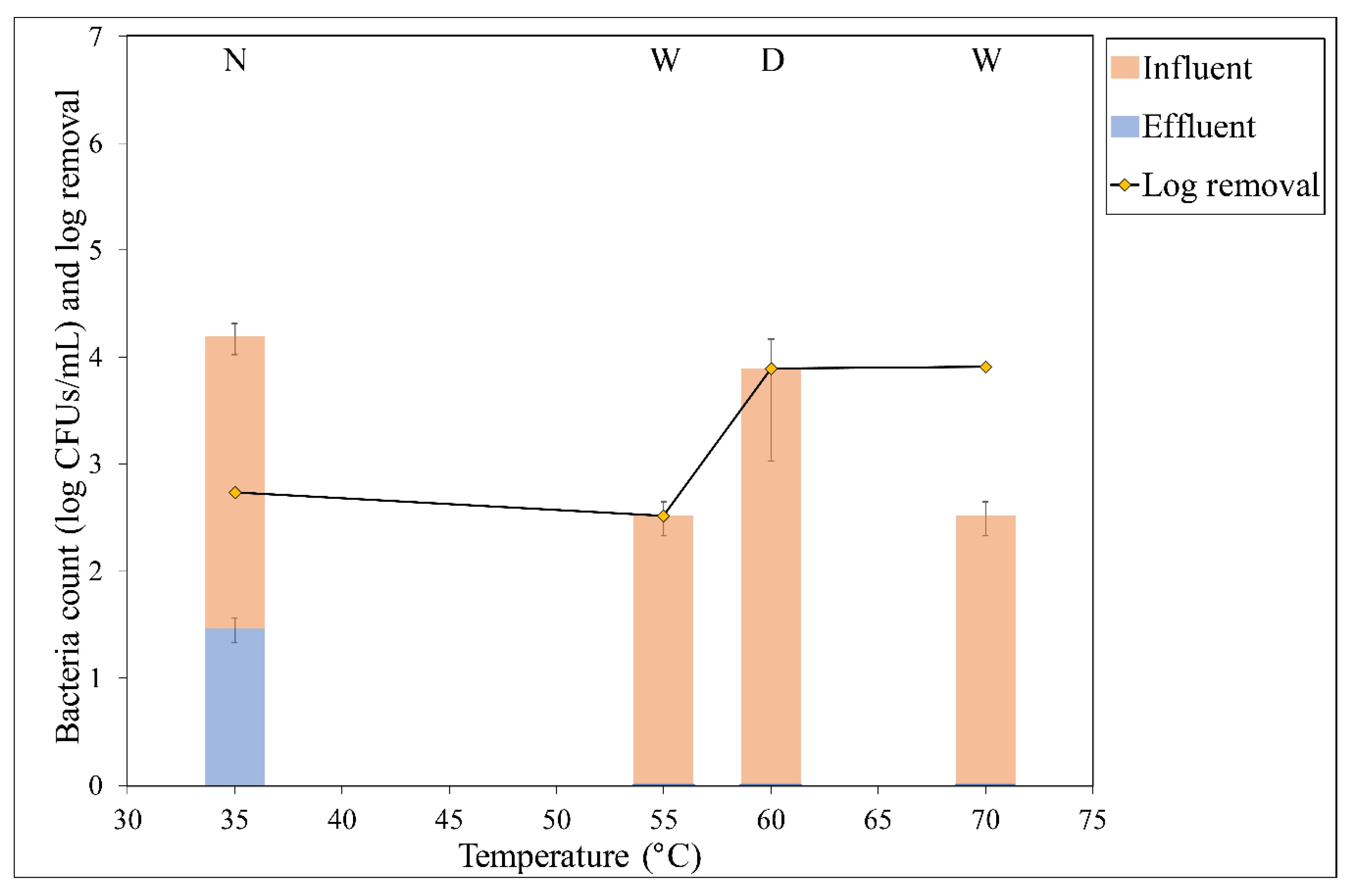

3.1. Removal at Each Temperature

3.2. Effect of Temperature

3.3. Next Steps in Process Optimization

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Desmidt, E.; Ghyselbrecht, K.; Zhang, Y.; Pinoy, L.; Van der Bruggen, B.; Verstraete, W.; Rabaey, K.; Meesschaert, B. Global phosphorus scarcity and full-scale p-recovery techniques: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 336–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordell, D.; Drangert, J.-O.; White, S. The story of phosphorus: Global food security and food for thought. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, C.M.; Khunjar, W.O.; Nguyen, V.; Tait, S.; Batstone, D.J. Technologies to recover nutrients from waste streams: A critical review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 385–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ciceri, D.; Manning, D.A.C.; Allanore, A. Historical and technical developments of potassium resources. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 502, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, J.; Lijmbach, D.; Steen, I. Why recover phosphorus for recycling, and how? Environ. Technol. 1999, 20, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeman, G.; Kujawa-Roeleveld, K. Resource recovery from source separated domestic waste(water) streams; full scale results. Water Sci. Technol. 2011, 64, 1987–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaff, M.S.; Temmink, H.; Zeeman, G.; Buisman, C.J.N. Anaerobic treatment of concentrated black water in a UASB reactor at a short HRT. Water 2010, 2, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tervahauta, T.; Rani, S.; Hernández Leal, L.; Buisman, C.J.N.; Zeeman, G. Black water sludge reuse in agriculture: Are heavy metals a problem? J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 274, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, R.; van Hell, A.J. Nieuwe Sanitatie Noorderhoek, Sneek: Deelonderzoeken; Rapport: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zeeman, G.; Kujawa, K. Anaerobic treatment of source separated domestic wastewater. In Source Separation and Decentralization for Wastewater Management; Larsen, T.A., Udert, K.M., Lienert, J., Eds.; IWA-Publishing: London, UK, 2013; pp. 307–319. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, M.; Zhang, L.; Florentino, A.P.; Liu, Y. Performance of anaerobic treatment of blackwater collected from different toilet flushing systems: Can we achieve both energy recovery and water conservation? J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 365, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; El-Khateeb, M.; Regelsberger, M.; El-Sheikh, R.; Shehata, M. Integrated system for the treatment of blackwater and greywater via UASB and constructed wetland in Egypt. Desal. Water Treat. 2009, 8, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Grinten, E.; Spijker, J.; Lijzen, J.P.A. Hergebruik van grondstoffen uit afvalwater. RIVM Briefrapport 2015-0206; Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu (RIVM): Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen-Tanski, H.; van Wijk-Sijbesma, C. Human excreta for plant production. Biores. Technol. 2005, 96, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, P. Land application of treated sewage sludge: Quantifying pathogen risks from consumption of crops. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 98, 380–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, M. Occurrence and removal of antibiotic resistance genes in municipal wastewater and rural domestic sewage treatment systems in eastern china. Environ. Int. 2013, 55, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaia, C.M.; Rocha, J.; Scaccia, N.; Marano, R.; Radu, E.; Biancullo, F.; Cerqueira, F.; Fortunato, G.; Iakovides, I.C.; Zammit, I.; et al. Antibiotic resistance in wastewater treatment plants: Tackling the black box. Environ. Int. 2018, 115, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, D.L.; LaPara, T.M. Effect of temperature on the fate of genes encoding tetracycline resistance and the integrase of class 1 integrons within anaerobic and aerobic digesters treating municipal wastewater solids. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 9128–9133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Munir, M.; Xagoraraki, I. Correlation of tetracycline and sulfonamide antibiotics with corresponding resistance genes and resistant bacteria in a conventional municipal wastewater treatment plant. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 421, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.Y.; Shen, Q.; Zhao, F.J. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance from animal manures to soil: A review. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2018, 69, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tasho, R.P.; Cho, J.Y. Veterinary antibiotics in animal waste, its distribution in soil and uptake by plants: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 563-564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppusamy, S.; Dhatri, K.; Kadiyala, V.; Mallavarapu, M.; Young-Eun, Y.; Yong Bok, L. Veterinary antibiotics (VAs) contamination as a global agro-ecological issue: A critical view. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 257, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Gu, J.; Sun, W.; Wang, X.-J.; Su, J.-Q.; Stedfeld, R. Diversity, abundance, and persistence of antibiotic resistance genes in various types of animal manure following industrial composting. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. The Global Risks Report 2020; WEF: Geneve, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. WHO Global Strategy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance; WHO: Geneve, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Zheng, J.; Tian, S.; Liu, C.; Liu, L.; Wei, L.; Fan, H.; Zhang, T.; Wang, L.; Zhu, G. Higher temperatures do not always achieve better antibiotic resistance gene removal in anaerobic digestion of swine manure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gothwal, R.; Shashidhar, T. Antibiotic pollution in the environment: A. review. CLEAN Soil Air Water 2015, 43, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, G.; Jiang, M.; Chen, H.; Sun, M.; Liu, Y.F.; Li, X.; Gao, P. Critical review of args reduction behavior in various sludge and sewage treatment processes in wastewater treatment plants. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 49, 1623–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Guo, M. Residual veterinary pharmaceuticals in animal manures and their environmental behaviors in soils. In Applied Manure and Nutrient Chemistry for Sustainable Agriculture and Environment; He, Z., Zhang, H., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Hu, H.-W.; Chen, Q.-L.; Singh, B.K.; Yan, H.; Chen, D.; He, J.-Z. Transfer of antibiotic resistance from manure-amended soils to vegetable microbiomes. Environ. Int. 2019, 130, 104912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepper, I.L.; Brooks, J.P.; Gerba, C.P. Antibiotic resistant bacteria in municipal wastes: Is there reason for concern? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 3949–3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, K.; Chen, J.; Zhou, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, Q.; Wei, Z. Host bacterial community of mges determines the risk of horizontal gene transfer during composting of different animal manures. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 250, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, B.; Yang, M. Changes of resistome, mobilome and potential hosts of antibiotic resistance genes during the transformation of anaerobic digestion from mesophilic to thermophilic. Water Res. 2016, 98, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengeløv, G.; Agersø, Y.; Halling-Sørensen, B.; Baloda, S.B.; ersen, J.S.; Jensen, L.B. Bacterial antibiotic resistance levels in danish farmland as a result of treatment with pig manure slurry. Environ. Int. 2003, 28, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šunta, U.; Žitnik, M.; Finocchiaro, N.C.; Bulc, T.G.; Torkar, K.G. Faecal indicator bacteria and antibiotic-resistant β-lactamase producing escherichia coli in blackwater: A pilot study. Arch. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol. 2019, 70, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liao, H.; Lu, X.; Rensing, C.; Friman, V.P.; Geisen, S.; Chen, Z.; Yu, Z.; Wei, Z.; Zhou, S.; Zhu, Y. Hyperthermophilic composting accelerates the removal of antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements in sewage sludge. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dumontet, S.; Dinel, H.; Baloda, S. Pathogen reduction in sewage sludge by composting and other biological treatments: A review. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 1999, 16, 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjerstadius, H.; la Cour Jansen, J.; De Vrieze, J.; Haghighatafshar, S.; Davidsson, Å. Hygienization of sludge through anaerobic digestion at 35, 55 and 60 °C. Water Sci. Technol. 2013, 68, 2234–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendixen, H.J. Safeguards against pathogens in danish biogas plants. Water Sci. Technol. 1994, 30, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, M.D.; Mullennix, R.W. Another look at thermophilic anaerobic digestion of wastewater sludge. Water Environ. Res. 1992, 64, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidaki, I.; Ahring, B.K. Anaerobic thermophilic digestion of manure at different ammonia loads: Effect of temperature. Water Res. 1994, 28, 727–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmerdahl Olsen, J.; Errebo Larsen, H. Bacterial decimation times in anaerobic digestions of animal slurries. Biol. Wastes 1987, 21, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon, P.; Magajna, B.; Lofranco, C.; Leung, K.T. Microbial indicators of faecal contamination in water: A current perspective. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2005, 166, 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendland, C. Anaerobic Digestion of Blackwater and Kitchen Refuse; Technische Universität Hamburg: Hamburg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, R.; Tachi, C.; Yasuda, K.; Hirata, T.; Noguchi, M.; Hara-Yamamura, H.; Yamamoto-Ikemoto, R.; Watanabe, T. Estimated discharge of antibiotic-resistant bacteria from combined sewer overflows of urban sewage system. NPJ Clean Water 2020, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hansen, W.; Yourassowsky, E. Detection of beta-glucuronidase in lactose-fermenting members of the family Enterobacteriaceae and its presence in bacterial urine cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1984, 20, 1177–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shaikh, S.; Fatima, J.; Shakil, S.; Rizvi, S.M.; Kamal, M.A. Antibiotic resistance and extended spectrum beta-lactamases: Types, epidemiology and treatment. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 22, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vinué, L.; Sáenz, Y.; Martínez, S.; Somalo, S.; Moreno, M.A.; Torres, C.; Zarazaga, M. Prevalence and diversity of extended-spectrum ß-lactamases in faecal escherichia coli isolates from healthy humans in spain. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2009, 15, 954–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nagpal, R.; Mainali, R.; Ahmadi, S.; Wang, S.; Singh, R.; Kavanagh, K.; Kitzman, D.W.; Kushugulova, A.; Marotta, F.; Yadav, H. Gut microbiome and aging: Physiological and mechanistic insights. Nutr. Healthy Aging 2018, 4, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beneragama, N.; Moriya, Y.; Yamashiro, T.; Iwasaki, M.; Lateef, S.A.; Ying, C.; Umetsu, K. The survival of cefazolin-resistant bacteria in mesophilic co-digestion of dairy manure and waste milk. Waste Manag. Res. 2013, 31, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, P.K.; Soupir, M.L. Escherichia coli inactivation kinetics in anaerobic digestion of dairy manure under moderate, mesophilic and thermophilic temperatures. AMB Express 2011, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, W.; Ling, N.; Guo, J.; Ruan, Y.; Wang, M.; Shen, Q.; Guo, S. Dynamics of the antibiotic resistome in agricultural soils amended with different sources of animal manures over three consecutive years. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 401, 123399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Qian, X.; Gu, J.; Wang, X.-J.; Duan, M.-L. Mechanism and effect of temperature on variations in antibiotic resistance genes during anaerobic digestion of dairy manure. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zou, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, H.; Fang, T.; Dong, P. New insight into fates of sulfonamide and tetracycline resistance genes and resistant bacteria during anaerobic digestion of manure at thermophilic and mesophilic temperatures. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 384, 121433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, W.; Sun, W.; Fan, Q.; Zhaohui, Y. Metagenomic approach reveals the fate of antibiotic resistance genes in a temperature-raising anaerobic digester treating municipal sewage sludge. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.M.; Shin, J.; Choi, S.; Shin, S.G.; Park, K.Y.; Cho, J.; Kim, Y.M. Fate of antibiotic resistance genes in mesophilic and thermophilic anaerobic digestion of chemically enhanced primary treatment (CEPT) sludge. Biores. Technol. 2017, 244, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, T.R.; Sadowsky, M.J.; LaPara, T.M. Modeling the fate of antibiotic resistance genes and class 1 integrons during thermophilic anaerobic digestion of municipal wastewater solids. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 1437–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, D.P.; Jensen, P.D.; Batstone, D.J. Methanosarcinaceae and acetate-oxidizing pathways dominate in high-rate thermophilic anaerobic digestion of waste-activated sludge. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 6491–6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ahring, B.K.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Mladenovska, Z. Effect of temperature increase from 55 to 65 °C on performance and microbial population dynamics of an anaerobic reactor treating cattle manure. Water Res. 2001, 35, 2446–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, M.D.; Walters, G.W.; Crunk, P.L.; Willis, J.L.; Farrell, J.B.; Schafer, P.L.; Arnett, C.; Turner, B.G. Laboratory evaluation of thermophilic-anaerobic digestion to produce Class A biosolids. 1. Stabilization performance of a continuous-flow reactor at low residence time. Water Environ. Res. 2005, 77, 3019–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lettinga, G.; Hulshoff Pol, L. UASB-process design for various types of wastewaters. Water Sci. Technol. 1991, 24, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaya Beas, R.E.; Ayala-Limaylla, C.; Kujawa-Roeleveld, K.; Lier, J.B.v.; Zeeman, G. Helminth egg removal capacity of UASB reactors under subtropical conditions. Water 2015, 7, 2402–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vinnerås, B.; Nordin, A.; Niwagaba, C.; Nyberg, K. Inactivation of bacteria and viruses in human urine depending on temperature and dilution rate. Water Res. 2008, 42, 4067–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, A.; Nyberg, K.; Vinnerås, B. Inactivation of Ascaris eggs in source-separated urine and feces by ammonia at ambient temperatures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aitken, M.D.; Sobsey, M.D.; Shehee, M.; Blauth, K.E.; Hill, V.R.; Farrell, J.B.; Nappier, S.P.; Walters, G.W.; Crunk, P.L.; Van Abel, N. Laboratory evaluation of thermophilic-anaerobic digestion to produce Class A biosolids. 2. Inactivation of pathogens and indicator organisms in a continuous-flow reactor followed by batch treatment. Water Environ. Res. 2005, 77, 3028–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Casas, M.E.; Ottosen, L.D.M.; Møller, H.B.; Bester, K. Removal of antibiotics during the anaerobic digestion of pig manure. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 603, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sampling | Noorderhoek | DeSaH | WUR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Sneek | Sneek | Wageningen | |

| Toilet system | Regular vacuum toilets (+ kitchen grinders) | Male ultra-low flush volume vacuum toilets | Male and female ultra-low flush volume vacuum toilets | |

| Urinal alternative | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Average flush volume | L | 1–1.5 | 0.7 | 0.2–0.8 |

| Temperature(s) | °C | 35 | 60 | 55 and 70 |

| Hydraulic retention time (HRT) | Days | 11 | 11 | 6–8 |

| Reactor volume | L | 40,000 | 500 | 4.9 |

| Sample period | 17 July 2018–11 July 2019 | 29 April 2019–11 July 2019 | 16 May 2019–04 September 2019 | |

| Samples | n | 9 | 5 | 8 |

| Users | 232 households, 192 family homes, 40 apartments for elderly people (nursing homes). A total of 330 residents. | Office building, 60 male employees | Working area, 80 people, mainly students and PhD students in the age of 20–35 | |

| Storage of black water (BW) prior to treatment | The BW and kitchen waste (KW) were stored for a brief period (a couple of hours) in an underground buffer vacuum tank. | The BW was stored in a well-mixed buffer tank for approximately 1.5 to 3 days at room temperature. | After collection, the BW was stored at room temperature in a mixed tank (V = 200 L) with an estimated retention time of 7 days prior to treatment in the reactors. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moerland, M.J.; Borneman, A.; Chatzopoulos, P.; Fraile, A.G.; van Eekert, M.H.A.; Zeeman, G.; Buisman, C.J.N. Increased (Antibiotic-Resistant) Pathogen Indicator Organism Removal during (Hyper-)Thermophilic Anaerobic Digestion of Concentrated Black Water for Safe Nutrient Recovery. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9336. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229336

Moerland MJ, Borneman A, Chatzopoulos P, Fraile AG, van Eekert MHA, Zeeman G, Buisman CJN. Increased (Antibiotic-Resistant) Pathogen Indicator Organism Removal during (Hyper-)Thermophilic Anaerobic Digestion of Concentrated Black Water for Safe Nutrient Recovery. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9336. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229336

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoerland, Marinus J., Alicia Borneman, Paraschos Chatzopoulos, Adrian Gonzalez Fraile, Miriam H. A. van Eekert, Grietje Zeeman, and Cees J. N. Buisman. 2020. "Increased (Antibiotic-Resistant) Pathogen Indicator Organism Removal during (Hyper-)Thermophilic Anaerobic Digestion of Concentrated Black Water for Safe Nutrient Recovery" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9336. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229336