1. Introduction

Wine tourism is generally viewed as a thematic way of spending leisure time, which involves the making and marketing of complex integrated tourism products. In this sector, wine represents a thematic pivot around which many different activities can be developed. While recognizing a focus on oenological productions, these activities aggregate interests coming from other cross-cutting sectors such as catering, accommodation, handcraft, culture, and art. As a matter of fact, the pull factors influencing the choices of wine tourists are not only related to visits to vineyards and wineries, but also to gastronomic events, wine festivals, cultural shows, and more widely to any other kind of experience tourists may have in a producing region that deepens wine culture and approaches the territorial dimension [

1].

During its first global conference on wine tourism, the UN World Tourism Organization—while referring to this tourist niche as one of the most promising in the market—defined it as an intimate part of a destination cultural identity and therefore as an important segment of the wider cultural tourism [

2]. The notion of a close interdependence between wine production, local heritage, lifestyle, environmental safeguards, and marketing has been widely shared in literature to address the sustainability-related issues [

3,

4,

5].

It is no coincidence that wine tourism has been defined as the best representation of the “wine and territory” combination [

6], providing unique experiences that include natural landscape, culture, traditions, artistic beauties, and atmosphere of a region [

7]. Furthermore, on the demand side, it has been revealed that wine tourists may prefer destinations that can offer a wider range of related services and activities [

8]. The challenge to integrate different economic sectors and to favor the cooperation among territorial economic actors is also an important issue within the relation between sustainable tourism and social development [

9].

In wine tourism, wine producers have found new market segments able to increase their business by offering new consumer goods and occasions with added experiential value [

10]. For all these reasons, wine tourism constitutes a substantial input to the multifunctional diversification of farms, which is the primary driver of agricultural landscape conservation and, therefore, of rural territories’ attractiveness [

11]. One of the main tools for the development of the phenomenon of wine-tourism has been the so-called “wine-routes”. If—in an objective sense—a wine route is aimed at organizing a physical network through a specific reorganization of the roads and their signage in a wine producing area connecting different locations in a territory, then subjective connotations give more importance to symbolic aspects [

12]. Such connotations are largely related to the ability to solicit feelings and emotions from those who travel along a route, while also addressing their immaterial needs (motivations and experiences).

Wine routes are usually proposed as the most comprehensive and successful way for organizing thematic networks able to increase the potential of wine tourism [

13,

14], in relation to the local cultures. They may provide economic and sociocultural benefits within a tourist destination [

15] and promote wine tourism business practices [

5,

16], according to sociocultural and economic sustainability. Tzimitra-Kalogianni et al. [

17] consider the wine routes to be a way of acquainting consumers with the various stages of wine production, the differences between wine types, and general knowledge about wine culture.

Several studies have focused on the factors limiting the potential of wine routes in different countries. In Chile, for example, the wine routes potential in terms of sustainable development has been also limited by low coordination and governance between public and private companies and lack of synergies with other tourism sectors [

18]. In an exploratory study on the Stellenbosch Wine Route in South Africa, wineries perceive some aspects of wine tourism as being advantageous to their business even if they are not organized to derive the maximum benefit from them [

19].

Against this background, one could speak of complex dynamics of “route-making”, that is the unfolding of a specific organizational model, whose process of implementation revolves around the notion of the sustainable social construction of a tourist product [

9,

20]. This means that the transformation of a set of locations into a “wine route” requires a social reorganization of several territorial assets. If, on the one side, this process is firstly aimed at providing the visitors/tourists with the distinctive cultural signifier they are looking for, on the other hand it requires to be socially sustainable and inclusive. All different local actors (i.e., entrepreneurs, administrators, farmers, tour operators, restaurateurs) need to get involved in order to innovate and integrate their offer into a wider territorial tourist supply, interconnecting with one another the cultural, social, and environmental sustainability. They need to take on a series of actions in order to develop a specific product that comprises several elements also aimed at ensuring the environmental and cultural sustainability, such as landscape beauty (i.e., winescape), rural settlements architecture, food and wine quality, nature safeguards, etc. The elaboration of such a product is then the result of a complex decision-making process that implies both goods and services, supplied by a variety of providers. This process combines hard core factors (vineyards and wineries, regional products, accessibility and usability of locations, accommodation, and catering facilities) with soft factors (quality of goods and services, aesthetics of the landscape, local culture, branding, the operators’ professionalism). More generally, it is a transformational process that has to turn simple production areas into tourist destinations [

21].

In the light of this reasoning, this paper is aimed at investigating wine companies’ perceptions and attitudes towards the role of wine routes as an actual and potential tool to innovate their business and the territorial supply chain in terms of tourist enhancement and regional attractiveness as well as to favor their participation in territorial development processes.

1.1. Wine Routes, Network Approach and Organisational Aspects

In the light of the above considerations, and with a specific focus on stakeholders, wine routes may employ a network strategy aiming at responding to social sustainability principles. A certain number of companies gather around a key product (wine) that characterizes them and generally gives them the name. The services offered are composed of a variety of product-related activities (i.e., visits to production sites, wine tasting, participation in harvesting, and winemaking). These thematic routes can therefore be considered as an integrated project that allow stakeholders to recognize and exploit a production process for the purpose of attracting tourists in a more structured way. They create a network that links together the various actors of a territory, producing structural coherence between a variety of symbolic elements and material goods, such as wine products, culture and landscape. Its overall organization is determined by collective action [

22,

23] and by the engagement in relationships with other hospitality operators [

24].

By choosing among all the possible proposals, this study suggests applying the “network paradigm” developed by Murdoch [

25] to the wine tourism field for innovation in rural development. On the basis of such an approach, tourism development would be considered as a proactive field, aiming at linking horizontal-to-vertical networks together into a whole. Whereas the horizontal network (which is almost thoroughly endogenous) would enable the consolidation of the farmers’ multifunctionality and the coordination of the various economic activities within the same area, the vertical one would pursue the objective of placing the wine routes on the wider travel chains at both a national and an international level. Such an approach would allow local actors, on the one hand, to reorganize and strengthen local production capacities and, on the other, to gain access to new markets and other economic opportunities. It is obvious that the concepts of “development of destination” and “networking” are two sides of the same coin since the former would be unthinkable without any reference to the latter [

26].

Though they have a basic applicability to any type of destination, these reference frameworks show particular usefulness and validity in the wine routes contexts, where private businesses operate on a micro level. Indeed, despite the apparent “simplicity” of such economies, the interaction between elements can become surprisingly complex, leading to new problems—from relations with institutions, environmental protection, and enhancement of services to landscape conservation; from economic growth to social justice, from the improvement of infrastructure to the enhancement of culture, just to name a few—that cannot fail to draw attention to the central role the relationship between the stakeholders and the content plays, also in terms of environmental and social sustainability.

If the destination-oriented research remains a major theme of investigation in wine tourism literature, less attention is usually given to companies’ decision making and strategy, and in general to innovation processes [

27]. The wineries’ keepers and other stakeholders’ behaviors and their involvement in the wine routes making and management seem to be a fruitful and not fully explored field of research. In this respect, the analysis of the perception of the single operators could assume great importance, mainly when the networks involve companies from different sectors, and public and private actors [

28].

The wine route itself can be defined as “a network of agents in a wine region, whose purpose is to promote regional development by employing strategies that lead to the development of an inclusive regional network which encompasses public and private agents from both sectors of activity (wine and tourism)” [

29].

Networking is as necessary as critical, since it requires the need to create a linkage between companies that perceive themselves as belonging to different businesses fields. As complex and multi-sectorial networks, wine routes should involve wineries and other businesses, such as accommodation, restaurants, cultural, tourist services, local food producers, and handcraft [

13,

30,

31], also responding to sustainable tourism approaches. Furthermore, networking needs resource sharing among companies that would consider themselves as competitors [

32]. Therefore, intra-sectoral coopetition and inter-sectoral cooperation have to be considered.

Usually, wineries are moved by the advantages coming from a potential increase in sales and profits, branding, and customers’ relationships development, but they should also take into account the necessity to reorganize their activity and business as a whole [

32]. Innovative companies seek differentiation and are constantly reconciling internal objectives with new market opportunities and changes within the institutional framework. Orienting company operations towards wine tourism networking requires organizational changes and may occur as a result of internal drivers and external pressures driven by institutional factors, which can ensure social legitimacy [

33].

Furthermore, the network is composed by both public and private stakeholders, who can have different objectives and different points of view, in a perspective of destination management and territorial development [

34].

Destination effective governance and competitiveness highly depend on their capacity of coordination and collaboration [

30]. A wine route making requires necessarily an organizational structure to manage and animate the coordinated activities and the collective actions. It could be a new or an already existing wine-related institution (like a Consortium) and involve both public and private organizations. Different activities can be developed to support the wine routes, such as marketing intelligence for wineries, organization of events, communication plans, research activities, tour packages, and quality criteria for products and services [

35].

Even if the concept of network seems to be the most appropriate to represent the structure of a wine route, it is often unperceived by the wineries themselves. While analyzing three Italian wine routes through in-depth stakeholders’ interviews, Bregoli et al. [

30], underlines that only a minority considers the wine route as a network of stakeholders, while the majority identifies a wine route as a new project to start, allowing the achievement of specific goals. These aims are the promotion of the place, the creation of new tourism products, or simply the promotion of wine and the increase in their own wine selling.

Wineries often do not completely perceive the benefits that tourism may produce. Some of them have poor skills in tourism, marketing, and tourist product development, their activities being predominantly product-oriented rather than market-oriented [

36]. Furthermore, the limitation in cross-sectoral networking (mainly with tourist companies or cultural associations) does not help overcoming these limitations. The lack of leadership and of a clear definition of what a wine route is or could be can increase their scarce participation in a wine route. Therefore, a lack of collaboration could be considered as a consequence of different perceptions and lack of trust among stakeholders [

30].

Funding is another key issue about wine route success. Investments for long-term development should have priority over short-term funds [

37]. On the other hand, the level of co-participation of the companies in the wine route funding can be considered an issue related not only to the acquisition of resources but also to the involvement and adhesion to the wine route objectives.

1.2. Aims of the Study

Based on the issues related to the networking paradigm and to the organizational aspects of wine tourism funding and management, the study is aimed at investigating under which conditions wine routes are perceived by the wine companies as a useful means for the improvement of their tourist attractiveness. The activities and the management aspects of the wine routes are considered in relation with the wineries’ satisfaction. The hypothesis is that the satisfaction is somehow related to two main aspects: the level of complexity of the activities promoted within the wine routes, and the direct involvement of the companies in the management, funding, and organization of the routes. Both aspects have to do with the conscious and active role wineries can play throughout the process of routes development.

Using a mixed quantitative and qualitative approach, the case of the wine routes of the Abruzzo region has been compared to the Chianti Classico route in Tuscany, it being one of the most popular and successful wine destinations in Italy.

A direct on-line-survey was addressed to the wine companies involved in the wine routes in both regions. It was aimed at investigating the tourist services offered at single companies and at network level, and the companies’ satisfaction about wine routes. In-depth personal interviews to the main actors of the wine sector in both regions (such as the presidents of the consortia and wine routes and regional authorities) allowed the authors to collect qualitative data and explore the issues in more detail, considering the role of both network building and governance systems. In particular, during the interviews, the following topics have been analyzed: the organizational structure of the wine routes, the relational network, the perceptions of the wineries concerning the benefits that tourism can produce, and the typology of funding available.

Particular attention has been focused on the wineries’ perception in relation to their satisfaction about the current wine route management, their perception of the current and future importance of the wine routes in wine tourism development and, finally, their availability in funding the wine routes enhancement in the future.

1.3. The Wine Routes in the Italian Regions

The first Italian wine route was realized in Veneto in the 1960s in the heart of the Prosecco area and was named “La Strada del Vino Bianco” (The White Wine Route). It was a physical path of 45 km inaugurated in 1966 and inspired by the model of the “Deutsche Weinstraße”, an itinerary created in the 1930s between the Reno and Mosella valleys [

38].

Italian wine routes, as formal territorial organizations aiming at managing wine and food itineraries, are governed by Law No. 268/1999, which sets the guidelines at a national level and defers the application of more specific provisions to the regional level. According to the definition given by the Italian legislation, a “wine route” is “a route marked and advertised with special signs, characterized by important natural, cultural and environmental values, where one can visit vineyards and wineries of a single farm or associated ones”.

Italy is now the European country with the highest number of wine itineraries, counting 139 officially recognized wine routes [

39], compared to 19 in Spain, 15 in France and 11 in Portugal [

40].

Even if these numbers confirm the importance of the wine tourism phenomenon in Italy, several issues still limit a full achievement of the opportunities it could offer [

28]. Most Italian wineries are involved in wine tourism and are conscious of the benefits it could bring, but yet they propose mainly traditional services (e.g., wine tasting, cellar door sales, etc.), as our interviewees have confirmed. More innovative activities are less developed. Furthermore, they still use traditional promotional and communication tools, whereas social media marketing activities are less developed [

41]. A modest level of collaboration and a modest level of resource-sharing emerges in Italian small and micro wineries. They preferably collaborate with event managers, restaurants, and other wineries, mainly on the spot, for the organization of single events, experiences, and promotional activities [

42]. Therefore, a limited duration of collaboration is privileged compared to long term commitments and resources investments.

This study focuses on the wine routes of Abruzzo, one of the main wine producing regions in Italy in terms of cultivated land and wine production (33,078 hectares and 3.4 million hectoliters, respectively, in 2018) [

43]. Beside Abruzzo wine routes, a case study from a Tuscany route is taken into consideration in order to analyze both similarities and differences and to highlight the characteristics that may help cope with weaknesses. Tuscany has approximately the same level of wine production as Abruzzo, but its wines have gained a more successful image and it has boasted a stronger organization of the wine tourism sector.

The “Abruzzo wine routes” consist of six wine tourism itineraries distributed across the four provinces of the region. The project of setting up the wine routes was entrusted by regional law (LR 101/2000) to the Regional Agency for Agricultural Development Services and co-financed by the European Union. The project led to the signage of roads and enterprises as well as to a set of promotional activities [

44].

In 1996, Tuscany was the first Italian region to draw up a specific law on wine routes (LR 69/1996), formalizing already existing spontaneous initiatives. Twenty different wine tourist itineraries have been officially listed so far. Among these, the “Chianti Classico Wine and Oil Road” was selected for the survey. The Chianti Classico area is a hill territory between the provinces of Siena and Florence, and the most popular product is the PDO wine Chianti Classico DOCG (Controlled and Guaranteed Denomination of Origin), easily recognizable by the collective brand “Gallo Nero” (Black Cock), the best-known collective brand of the region, which has been used since 1924 [

45].

Even if referring to the same legislative framework at national level, the organizational context of the two typologies of wine-routes (the Abruzzo and the Chianti Classico ones) are very different, as our key informants have stated during the interviews. In the Abruzzo region, the foundation of the wine routes was realized thanks to an initial public investment with a top-down approach, which identified the itineraries and addressed the provision of material infrastructures. However, this investment was not followed by the establishment of an organized system of governance and by the management of coordinated activities, eventually referring to the single companies the initiative to organize their tourist offer. Furthermore, the Consortium for the protection of the PDO regional wines (Consorzio di Tutela Vini d’Abruzzo) has not used the itineraries identified by the wine routes as a means for the companies’ promotion.

In the Tuscan context, the existing spontaneous initiatives were organized into formal associations at territorial level, with a system of governance involving the key actors of the vine territories. In the case of Chianti Classico the wine route is managed by a public/private association, involving wineries, oil, and other typical products producers, tourist enterprises, municipalities, and cultural associations and, finally, the Consortium for the protection of the PDO wine Chianti Classico, holder of the collective brand. Furthermore, in Tuscany, the horizontal networks of the wine routes are integrated with vertical networking in a regional Wine Routes Association (Federazione Strade del Vino dell’Olio e dei Sapori di Toscana), involving the single territorial wine routes and the regional authority, with the purpose of exploiting the regional brand of “Tuscany”. Therefore, the two cases seem to highlight a completely different process, apparently with equal different outcomes. While in Abruzzo these itineraries have been created by the regional authorities on the base of a “desk work” (ex-ante constitution), in Tuscany their institutionalization has formalized an already existing and active network (ex post constitution).

2. Methodology of the Study

The quantitative survey was carried out using an on-line questionnaire. It was addressed to all the wineries that comprise the six wine routes of the Abruzzo region as well as those of the Chianti Classico route in Tuscany. The quantitative survey was integrated by qualitative in-depth interviews to the key actors of the local networks. The content of the interviews was developed on the basis of the literature reviewed about networking, social organization of the tourist offer, management aspects, and relational dynamics within wine routes foundation and development [

30].

The questionnaire was divided into two different sections:

- (1)

In the first one, which had the aim of describing the wine tourist demand and offer, questions about the following topics were asked:

The tourist services provided by the wineries;

The offered products (different wine typologies and other food products);

The visitors’ origin (Italian or foreign);

Their average expenditure per day;

The busiest visitor months;

The organization of the tourist offer (opening days, presence of dedicated personnel);

The impact of the tourist activities on the companies’ revenues.

- (2)

In the second one, which focused on the perception of the wineries about the wine routes organization, governance, and effectiveness in attracting tourists, the following items were analyzed:

Percentage of tourists visiting wineries while travelling on the wine route (5-points Likert scale, from None to All);

Contribution of the wine route to the development of wine tourism (5-points Likert scale, from Not at all to Very much);

Increase in visibility conferred on the companies and their products by the wine route (5-points Likert scale, from None to Very high);

The interventions made within the wine route;

The strengths and weaknesses of the wine route;

The development potential of the wine route;

The wineries’ past investments and their willingness to invest in the future for the improvement of the services offered within the wine route.

The list of the wineries was gathered from the official guide to the wine routes produced by the Abruzzo Region [

44] and by the official website of the Chianti Classico Wine and Oil Road (

http://www.stradachianticlassico.it/). All the enterprises included within the itineraries were invited to fill in the on-line questionnaire through a personal email followed by a direct telephone call. The survey was conducted in the months of January and February 2018. In total, 26 wineries out of the 42 listed in the Abruzzo Region guide participated in the study, and 12 out 26 of the Chianti Classico route in Tuscany did. The representativeness of the whole Abruzzo sample was 57.1%, while for Chianti it was 46.2%.

The data gathered through the quantitative survey were analyzed through both a descriptive and a multivariate analysis, which aimed at understanding either the positive or negative perceptions of the wineries concerning the current and potential role of the wine routes in increasing their business. The influence of some aspects of the wine tourist demand and/or the wine route management and services was considered.

The descriptive analysis focuses on comparing the situation in Abruzzo and Tuscany in terms of the wine tourism offer and its organizational models, whereas the multivariate analysis takes into consideration the wineries’ satisfaction, independently of their geographic location. In this latter case, the whole sample of the wineries (including both Tuscany and Abruzzo ones) has been considered. This option has pursued the aim of elaborating more general models for improvement in the services offered and in the governance of the wine routes in general.

The qualitative data were used both to deepen some insights coming from the survey and to identify the organizational structure model at the base of the wine routes activities. The mix between qualitative and quantitative data allowed the authors to elaborate an interpretive model and to come to some conclusions.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Main Characteristics of the Wine Companies

The companies interviewed show a similar average dimension in terms of workers: 16.9 working units per year for the Abruzzo companies and 14.5 for the Tuscan ones. All the companies promote activities related to visiting the wine cellars, wine tasting, and direct selling, but many offer a wider range of services, including visits to the vineyards (Abruzzo: 75%; Tuscany: 50%), agritourism activities (Abruzzo: 16.7%; Tuscany: 33.3%), naturalistic and/or artistic itineraries (Abruzzo: 20.8%; Tuscany: 8.3%), and cooking classes (Abruzzo: 8.3%; Tuscany: 16.7%). Results are in line with the broader survey of Del Chiappa et al. [

41] on a broader sample of 308 Italian wineries.

Generally, the wine offer is integrated with the sale of other products such as extra-virgin olive oil, liquors, preserves, and cheese. As far as the wine offer is concerned, in the enterprises from Abruzzo the sale of loose wine (33%) and box-wine (54%) is quite popular, whereas this service is not common in the Tuscan companies (where loose wine is only sold by 15% of them). This difference could be considered as an indicator of the different motivations of the visitors in the two areas. In Abruzzo, locals purchasing wine for daily use directly at the wine cellars (usually loose wine at a cheap price) has always been very common, whereas in Tuscany visits are mainly for touristic reasons.

Although the offer of products and services is not different across the board for the two regions, the Chianti wineries are more successful at running wine tourism activities. Most of the Tuscany companies value the impact of these activities on their revenues at between 16 and 30%, while most of the Abruzzo ones evaluate it being between 5 and 15%.

According to the interviewees, in 75% of the Abruzzo enterprises Italian visitors are more numerous, whereas in Tuscany, foreign tourists are in the majority in 92% of cases. Tourists’ provenance represents a very important issue for the companies’ business, as foreign people usually spend more than Italians. This difference between foreign and Italian tourists has been confirmed by several publications [

46,

47]. In both regions, most foreign tourists come from Germany, USA, France, and Switzerland, whereas the Italian tourists generally come from Northern and Central Italy.

The Italian visitors’ average expenditure per day shows a slightly higher value in the Chianti area (EUR 41–60 for 58.3% of the sample) than in Abruzzo (EUR 31–50 for 45.9% of the interviewees). In both regions, the foreign wine-tourists’ average expenditure is higher than EUR 60 (according to 58.3% of the interviewed companies from Tuscany and to 41.7% of the Abruzzo ones).

For the Abruzzo companies, the busiest visitor months are, respectively, July, August, and June, whereas according to the Tuscan companies, the flows are mainly spread evenly throughout the year, with peaks in June, September, May, and July. Actually, out-of-peak tourist flows in the Chianti area is enhanced by the presence of foreigners who visit Italy throughout the year. Therefore, it is important to underline that food and wine tourism has a deep connection with cultural tourism too [

48].

3.2. The Comparative Analysis

Starting from a comparative analysis of the Chianti and Abruzzo routes, it becomes clear that, whereas in the former region quite a large proportion of tourists (according to 83.3% of interviewees) arrive at the wine companies while travelling on a wine route, in the latter, “no” wine-tourists at all (58.3%) or just “a few” (41.7%) visit wineries as a result of a journey within a wine tourist itinerary.

Almost the whole of the Tuscany sample (83.3%) assesses that the wine route has played a prominent role in the development of local wine tourism. The companies from Abruzzo, instead, agree (87.5%) that the usefulness of the wine itineraries has been almost negligible for tourist purposes. Likewise, the Tuscany sample considers as positive the role of wine routes in increasing their company’s visibility (83.3%). Abruzzo’s enterprises (91.6%), on the contrary, agree that the usefulness of the wine routes has proved to be negligible for this purpose (

Table 1).

The material interventions made at the territorial level within the wine routes, as road signs and billboards, appear to be the most widespread and are common in both areas. Instead, the presence of the website and info points for the promotion of companies are very important in the Tuscan context, while in Abruzzo they have not yet been materialized (

Table 2).

With regard to strengths and weaknesses, the perception of companies in Tuscany was very different from that in Abruzzo. As a matter of fact, the weaknesses of the offer in Abruzzo correspond to the main elements of strength in Tuscany (

Table 3).

Nevertheless, there are elements that can be considered as weak points in both contexts and that could become areas of improvement for the organization of wine routes in general. These are: tourist promotion (through the intervention of specialized journalists, bloggers, and tour operators), cooperation between public and private sectors, and the availability of public funds. Other features considered useful for the improvement of the routes are cooperation among companies and the organization of events.

Despite the actual weaknesses, the companies in both samples (Abruzzo: 87.5%; Tuscany: 91.7%) believe that interventions aimed at the enhancement of the wine routes could have positive effects on their revenues, estimating a potential average increase of 21% of the companies’ revenue in Tuscany and 13% in Abruzzo.

With regard to the economic contribution of the companies to the development of the wine routes, the great majority of the Tuscan sample (66.7%) asserted that they had contributed economically in the past. For a high percentage (75%), their actual level of satisfaction made them open to financing future investments aimed at the implementation of new services offered to visitors. The majority of the Abruzzo sample (70.8%), on the other hand, specified that they had not given any financial contribution to the implementation of wine route interventions. In any case, they would be open (66.7%) to financing future interventions aimed at the improvement of the wine tourism itineraries.

3.3. The Driving Factors of the Companies’ Satisfaction

The purpose of this section of the analysis is to identify which aspects could influence companies’ positive perception. In particular, it investigates whether such a perception is influenced either by the number and features of wine tourists or by the activities promoted by and the overall organization of the wine routes. In other words: (a) the complexity of the offer; (b) the strengths of the wine routes perceived by the wineries; (c) the actual response from tourists (both domestic and international) in terms of average daily expenditure have been the variables this study has taken into account to assess wineries’ satisfaction within the wine routes experience.

In order to understand this, the whole sample of the surveyed enterprises (including those from both Abruzzo and Tuscany) has been analyzed. Moreover, to implement the analysis, some of the questionnaire answers have been recoded to set the model variables.

Variable “Satisfaction”—the chosen dependent variable is related to the perception the companies have about their level of satisfaction (shortly renamed “Satisfaction”). It was obtained as the average of the answers to the following questionnaire items (see

Table 1), recorded on a Likert scale with a score from 1 (equal to no effect at all) to 5 (equal to the maximum level of effect): the percentage of tourists who visit the winery while travelling on a wine route (item 1); the extent the presence of a wine route has affected the development of wine tourism in the area (item 2); the increase in visibility offered by the wine routes to the companies and their products (item 3). The variable is the average of the values given to the three different questions.

There are two aspects that need to be highlighted: (a) None of the companies included in the survey showed the highest level of satisfaction. The highest recorded value was 3 and the values of the mean and of the median coincide (this value is 2); (b) There is a clear correlation among the answers. The highest correlation is between the answers to item 1 and the answers to item 2 (0.79). The correlation between the answers to item 2 and the answers to item 3 is just slightly lower (0.72) and, finally, the correlation between the answers to item 1 and the answers to item 3 is the lowest (0.68).

The variable “Satisfaction” was then recoded into a new binary variable named “Level of satisfaction” composed of two different levels: “not satisfied” and “quite satisfied”, which are assigned, respectively, to values lower than the mean and to values equal or higher than the mean.

The majority of the companies (58%) consider themselves to be quite satisfied about the role of the wine routes, while the remaining (42%) are not satisfied at all. The percentage of satisfied companies is higher in Tuscany (92%) than in Abruzzo (42%).

Variable “Complexity”—the variable “Complexity” was obtained by recoding the answers given by the companies concerning the interventions made within the wine routes (see item 4 in

Table 2). The different activities were classified as “basic” (road signs, billboards, leaflets), “advanced” (website, advertising, info points, events) and “highly developed” (fairs, contacts with journalists, bloggers and tour operators, operators’ training, and tourist services). According to their level of complexity, basic activities were assigned the value 1, advanced the value 2, and highly developed the value 3. The answers “Nothing” or “Don’t know” have been assigned a value equal to zero (see

Table 4). In the case of companies indicating activities of different levels of complexity, the highest value has been assumed.

Variable “Strength”—the variable “Strength” was created using the answers companies gave to item 5 (see

Table 3), in which they were asked to point to strengths and weaknesses. The variable has been created by summing up the strengths each company pointed to.

In order to satisfy the research issues from a statistical-econometric point of view, a multiple linear regression model [

49] fitted with the Ordinary Least Squares (O.L.S.) technique was applied. After testing the model, the significance of each estimator as well as of the p-value of the F-test on the model was valued [

50]. Post-hoc tests were then performed in order to assess the basic assumptions of the model: linear relationship, normality, homoscedasticity, and no auto-correlation [

51]. All the models were fitted using R [

52] and R Studio [

53].

The purpose of such an analysis was to verify whether companies’ perception of satisfaction was influenced either by the tourist flows or by the organizational aspects that were measured by the complexity of interventions and by the strengths and weaknesses.

The considered response variable is “Satisfaction”, while the selected predictors are the variables “Complexity” and “Strength” (as illustrated above), the Italian tourists’ average daily expenditure (ExpIT), the foreign tourists average daily expenditure (ExpFO), and the ratio between Italian and foreign tourists (a dummy variable called “ItForRatio” which takes the value 0 when the percentage of foreign tourists is higher than the Italians ones; otherwise it takes the value 1).

The model is illustrated in Equation (1), in which “i” (from 1 to N) represents each of the interviewed companies.

Results are shown in

Table 5. This model offers some interesting insights. Firstly, only one of the predictors shows a statistically significant coefficient, that is “Complexity”. Secondly, the F-test indicates that the coefficient of determination is statistically significant (the value of R2 is non-zero), which means that the model has good explanatory power.

After removing all the variables with non-significant coefficient, the model expressed by Equation (2) was obtained:

Additionally, in this case, the F-test indicates that the coefficient of determination (R2) is significantly different from zero. Furthermore, the value of such a coefficient explains the 48% of variability of the response data (

Table 6).

After verifying that the model fits the data, the regression assumptions were assessed, as suggested by Kabacoff [

51]. The regression diagnostic shows that the assumptions of a linear relationship, normality and homoscedasticity, are valid. The Durbin–Watson test shows a

p-value of 0.14 and so the assumption that there is no auto-correlation is valid, too.

According to an economic view of the regression model, the results can be interpreted concisely as follows: the more complex the activities proposed along the wine routes are, the more satisfied are the companies. Satisfaction does not depend in a significant way on the ratio and difference in daily expenditure between Italian and foreign tourists, and not even on the actual perception of strengths and weaknesses of the wine routes which the companies belong to. It is possible to argue that the future perspectives—depending on the offered services—prevail on the actual effectiveness of the wine routes in terms of points of strengths and tourist presence or behaviors.

3.4. Companies’ Expectations about Wine Routes

For further verification of the proposed interpretation, the relation between the “Levels of satisfaction” and the perception of the future role of wine routes within the wineries’ development strategy was analyzed at the company level.

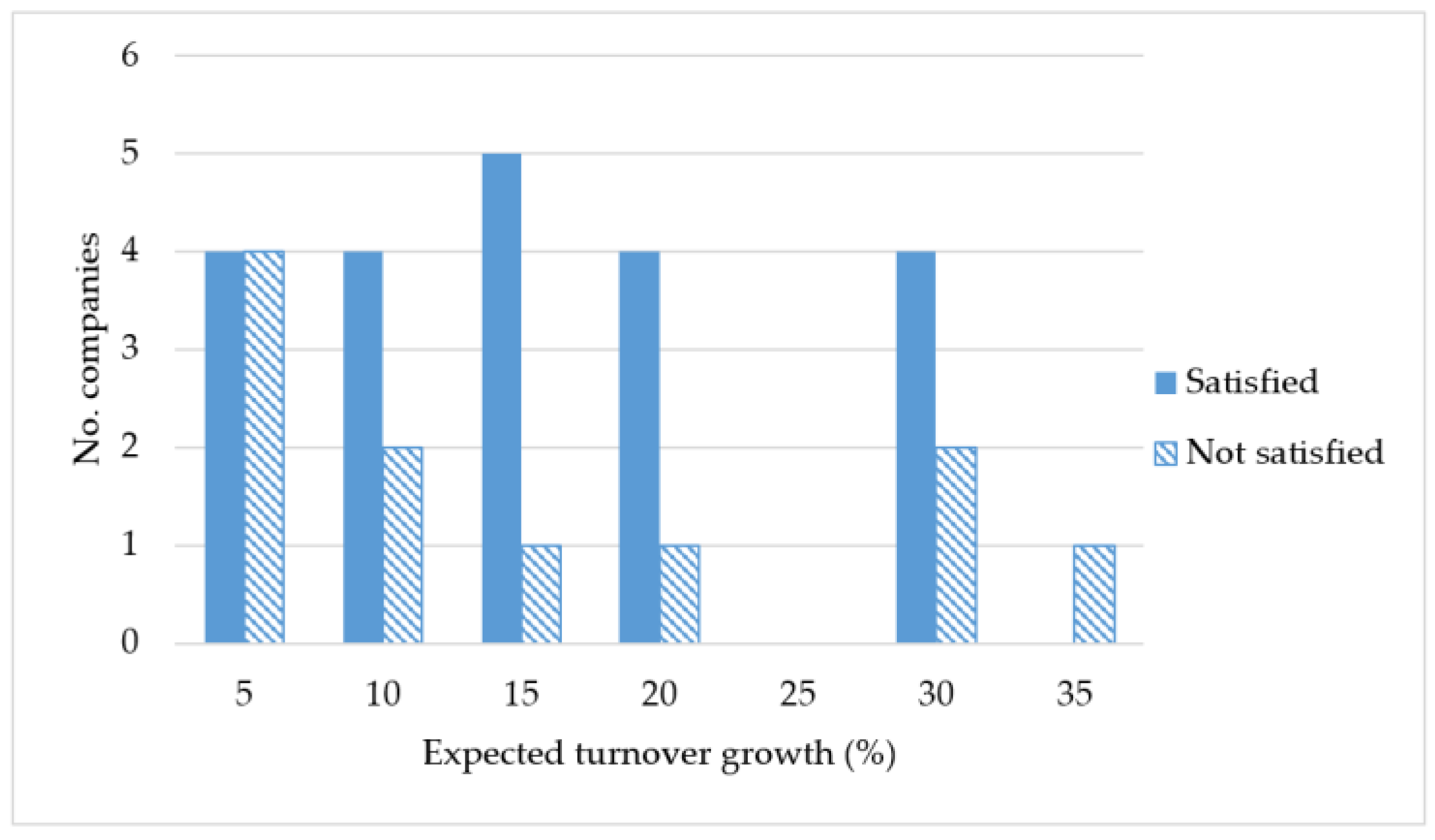

The first concern relates to the future potential enhancement of the wine routes. In particular, it is questioned whether their enhancement will have a positive impact on the companies’ revenues. The majority of companies has expressed a positive expectation. This point of view holds not only for all the happy enterprises (100%), but also 73.3% of the unhappy ones. The wineries quantify their positive expectation of growth being between 5% and 35% of the revenues of the previous year.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the companies per percentage value of expected growth of the turnover. The unsatisfied companies are polarized between a very low and a very high value, while the satisfied ones previsions are more equally distributed.

The second issue considered is openness to contributing to the future development of the services offered along the wine routes. In agreement with previous answers, the majority of the satisfied companies were willing to invest further in the wine routes (76.2%). However, it has to be noted that 60% of the unhappy companies were also open to investing in the development of the wine routes. This seems to suggest that the actual criticalities do not undermine wineries’ expectations about the potential role of the wine routes in the development of the tourism offer. These results confirm the findings by Correia et al. [

35], in which the wineries, despite the criticalities of the management of the route, were positive in respect to the future role of the route in increasing tourism and were willing to invest in the near future in wine tourism.

Finally, the strengths and the weaknesses (see

Table 3) were reconsidered by splitting the satisfied companies from the unsatisfied ones. The aim was to identify the areas of improvement in the governance and services offered by the wine routes, going beyond the geographical differences in order to obtain a more general point of view.

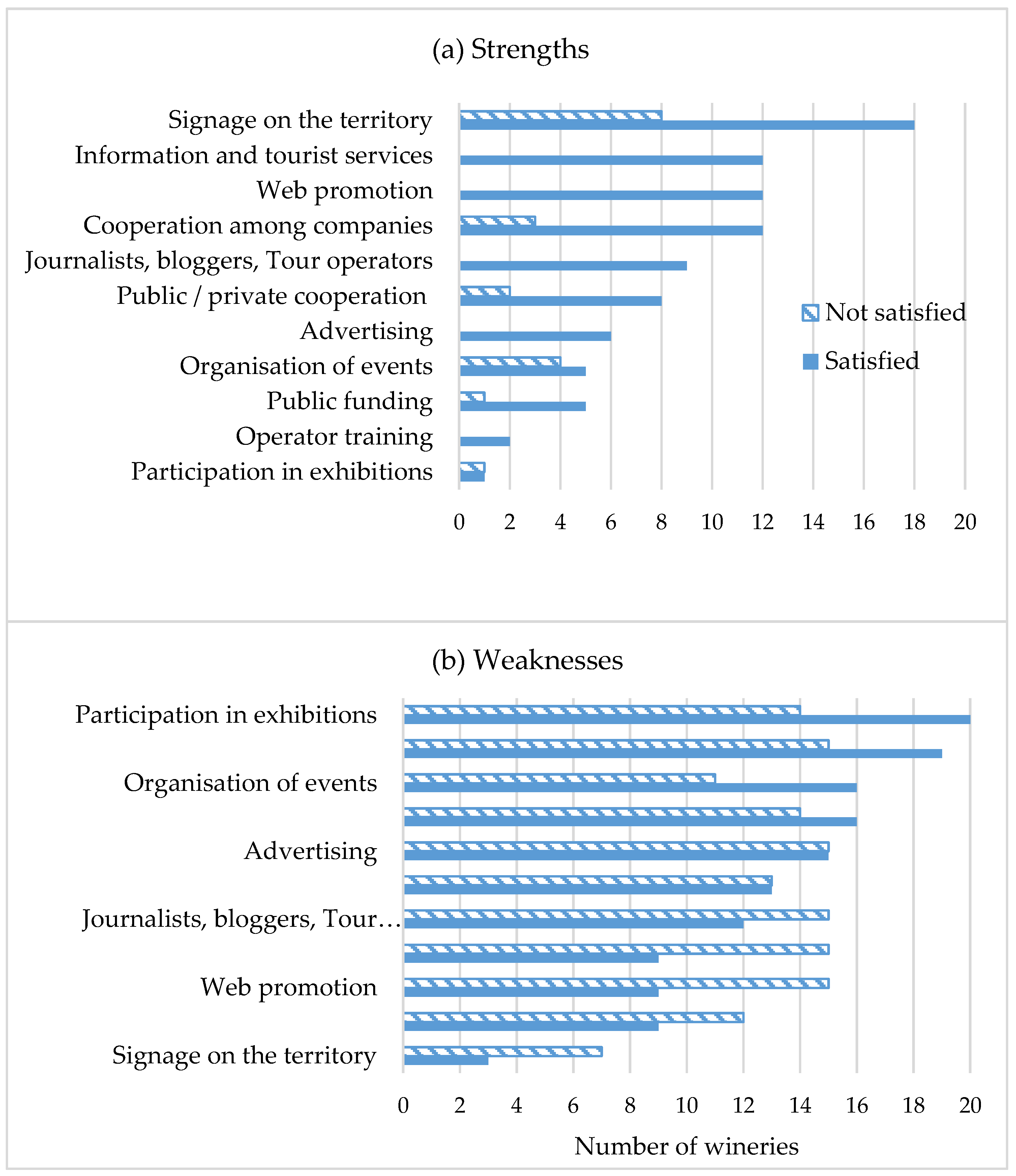

As expected, the satisfied companies (21 out of 36) presented a much higher number of points of strength than the unsatisfied ones (

Figure 2). Within this first group, the management aspect considered a point of strength by the majority of companies was the item “signage” (18 out of 21). This item was also the most positively scored by the unsatisfied companies (8 out of 15). The satisfied companies also stated as strengths cooperation among operators, web promotion, and organization of tourist services (12 scores for each element). By contrast, the operator training and the participation in exhibitions received very low scores.

The weaknesses present fewer differences between the two groups (

Figure 2). Especially those indicated by the satisfied companies can be considered as important insights for the further improvement in the management of wine routes. They are—in order of score—participation in fairs (20 out of 21), operator training (19), organization of events (16), public funding (16), advertising (15), and public/private cooperation (13).

These results are in line with other studies on Italian wine routes, which confirmed that the development of wine routes needs destination management initiatives, identifying the following as the main critical factors in the wine routes management: promotion; financial and community support; legislation and regional infrastructure; destination activities and training [

41].

4. Final Considerations

The research is aimed at verifying the conditions under which the wine routes could assume—in the perception of the wineries—a strategic role in the development of wine tourism. The statistical analysis highlights that the companies’ satisfaction about this role depends neither on the tourists’ provenience nor on their average daily expenditures. Instead, it appears tightly related to the activities undertaken within the wine routes, and therefore by the effectiveness of their management; that is, in the way they are socially constructed.

The actions that go beyond the pure material interventions are positively associated with the level of satisfaction stated by the companies. They concern on one side the management of the relationships with the tourist market—both those directed at the final customer (websites, information points, events organization) and those directed at the tourist chain (participation in exhibitions, relations with journalists, bloggers, tour operators)—and on the other side, the services offered to the wineries belonging to the route (operator training and guided tourist visits). These actions can be considered as “advanced” or “developed”. A hierarchical vision of actions emerges, not only in terms of numbers but especially in terms of complexity. The complexity of the interventions seems to influence the enterprises’ level of satisfaction in a positive way.

These results concur with the analysis of the actual strengths and weaknesses highlighted by the wineries. Even if the companies satisfied by the wine routes activities identify a higher number of points of strength than the unsatisfied ones, by the analysis of weaknesses some evidences about the actual challenges and the potential paths toward improvement emerge. Participation in exhibitions, operators training, advertising, public funding, and public/private cooperation are all weaknesses highlighted by both the satisfied and the unsatisfied companies. Therefore, the level of services and the governance of the wine routes could be still improved; also where the wine routes are already active, popular, and well organized.

Beyond the criticalities, the companies show confidence in the potential for business growth related to the enhancement of the wine routes, as emerges by their expectation on the turnover growth. The satisfied companies are mainly those who invested in the wine routes in the past and also those who showed a greater openness to repeating their investment in the future. At the same time, also a number of the unsatisfied companies (including the majority of the wineries in the Abruzzo region) are open to future investment. These results confirm former literature on the general confidence of the wineries in the potential of the wine routes [

35].

The comparison between the Abruzzo and the Tuscany cases allows us to take into consideration some policy, management, and governance issues.

As the Abruzzo region cases have shown, those interventions thoroughly funded by public resources and oriented towards a simple investment in material infrastructures or in promotional activities have not been completely effective. Instead, as shown in the Tuscany case study, interventions based on co-financing including private resources and developing a set of material and immaterial actions within a framework of a shared project and multilevel governance, have seemed to reach a greater level of efficacy. Therefore, co-financing—along with multilevel governance—could provide a way to improve and enhance the role of wine routes within local development processes. In particular, those measures proposed by the Rural Development Programs—in the framework of the European Union policies—based on the co-financing of the private investments within network projects could embody an important tool to help achieve this goal.

Concerning the management issues, in the Abruzzo region, the initial public investment, which addressed the provision of material infrastructures, was not followed by an organized system of management. By contrast, in Tuscany, the management of the wine routes is assured by public/private associations at the territorial level where horizontal networking (among the companies and other local actors) is integrated with vertical networking between the wine routes and the regional authority with the purpose of exploiting the regional brand “Tuscany”. A complex system of governance is realized, able to promote participation and private investments, assuring at the same time different levels of coordination.

The actual and potential role of the Consortia for the protection of the PDO wines also emerges, as underlined by the Chianti Classico stakeholders and other cases in the Tuscany region [

22]. Based on their already recognized leading role in representing the wineries, in defining the quality standards of the products and in promoting the denomination of origin, they should also play as leaders in the wine route management and realize a wider range of activities with the aim of promoting the territory as a whole: events organization, join participation in fairs, info points, tourist packages, and communication activities within the others. In this regard, it should be considered that without appropriate innovators and institutions leading the networks, the relationships may not be maintained, with a loss of innovation capacity and a loss of the opportunities wine tourism could provide for the companies and the wider territorial development [

36].

Multilevel governance and management systems seem even more relevant in times of rapid changes, when the companies have to readapt their business models to the emerging new market needs. A recent example of institutional collaboration in this direction is the International Protocol “Calm Enotourism”, elaborated by a Wine Tourism International Think Tank involving representatives of companies and associations [

54]. The protocol aims to guide the wineries and the operators of wine tourism in the readaptation of the structures and services towards the care and the safeguard of people, responding to the new COVID-19 related situation. The already existing network within the association has enabled a quick and efficient response to the new needs. At the same time, it might have been a valid support for the most fragile and disoriented companies, giving strength to social sustainability principles.

This experience, as well as the Tuscan one, poses the central role of cooperation and companies’ participation in terms of sustainable tourism development. All these elements can be considered as a base for elaborating a model useful to both Abruzzo and other wine regions. Strong tourist appeal together with private investments in territorial marketing and network strategies seem to be the key factors contributing to the success of the Tuscan wine routes. This confirms the importance of embracing a broader definition of wine routes, which includes a coordination structure for creating and managing networks rather than constructing and promoting a simple tourist itinerary. The study about possible strategies and policies able to favor this socio-cultural shift in the management of the wine routes could be at the base of future research paths.