Differences in the Quantitative Demographic Potential—A Comparative Study of Polish–German and Polish–Lithuanian Transborder Regions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Whether there are differences in shaping the quantitative demographic potential of border regions related to the time of joining the EU (East Germany in 1990, Poland and Lithuania in 2004) and the location against the EU borders (Polish–German transborder region—internal EU border, Polish-Lithuanian transborder regions—external EU border)?

- Does the marginal location of border regions in relation to centrally located urban centers affect the changes in the quantitative demographic potential?

- Will the quantitative demographic potential of the border regions of Poland and Lithuania approach the quantitative demographic potential of Germany or will it recede? Will the Polish border region experience a similar “urban shrinkage” process as in the German border region?

- Presenting and characterizing the diversity of demographic potential in quantitative terms and showing the impact of natural increase and migration balance on the size of this potential;

- Using comparative analysis of the demographic potential in the spatial system (Polish–German and Polish–Lithuanian cross-border);

- Conducting a comprehensive assessment of the diversity of the level of demographic potential in a synthetic approach and determining the directions of demographic development, which affect the regional policy of countries.

2. Materials and Methods

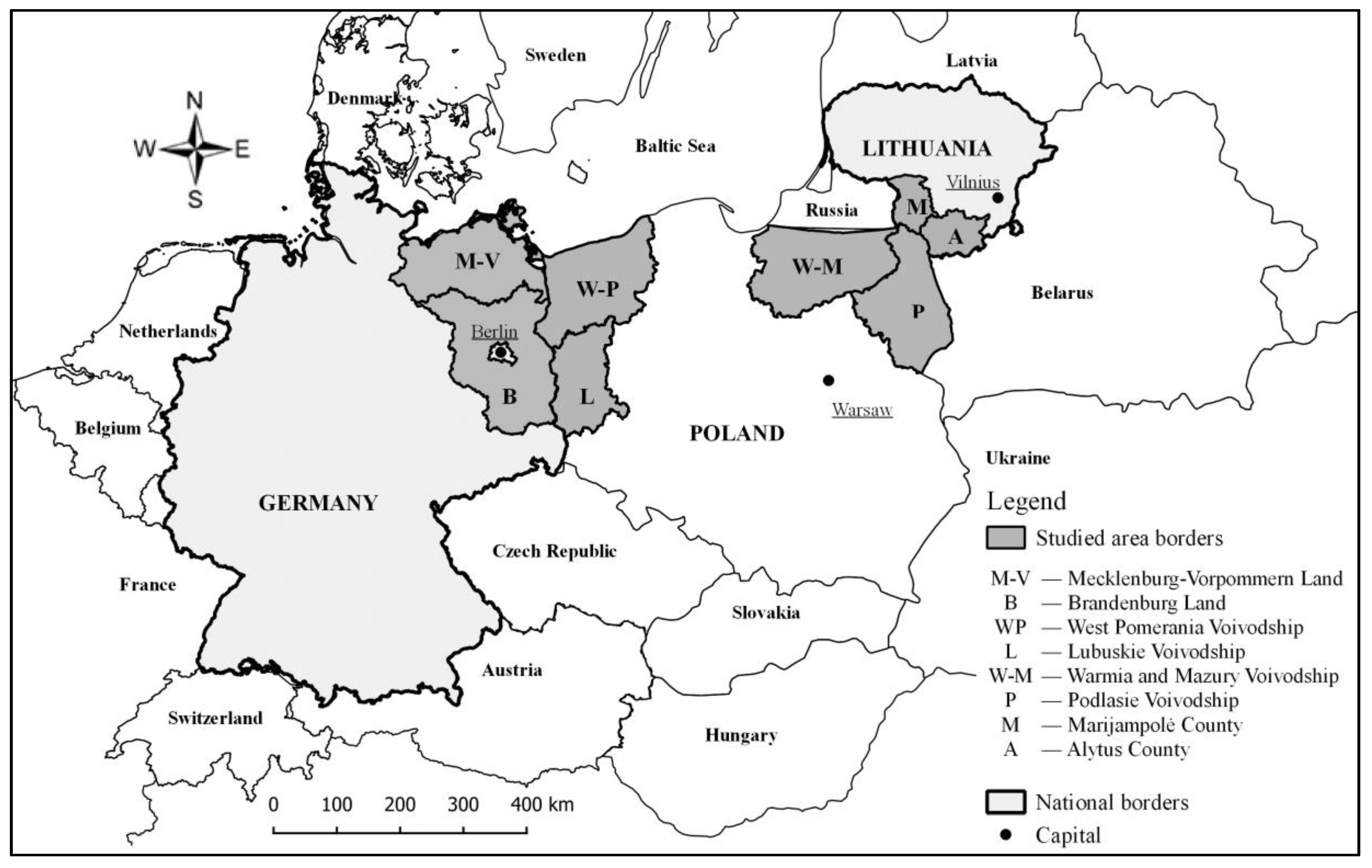

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Determinants of the Selection of the Research Area

2.2.1. Historical Impact of Demographic Changes

2.2.2. Natural Values

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Stage 1. Selection of Diagnostic Indicators

2.3.2. Stage 2. Statistical Analysis of Selected Indicators

2.3.3. Stage 3. Evaluation of Quantitative Demographic Potential Based on Its Constituent Elements (NUTS 0, NUTS 2, LAU 1) and in a Synthetic Approach (LAU 1)

Analysis of Quantitative Demographic Potential Based on Its Constituent Elements—NUTS 0 and NUTS 2 Levels

Analysis of Quantitative Demographic Potential Based on Its Constituent Elements and in a Synthetic Approach at LAU 1 Units

- Determination of synthetic indices for evaluating quantitative demographic potential

- Spatial distribution of quantitative demographic potential at LAU 1 units

2.3.4. Stage 4. Calculation of Real Growth as a Factor Influencing Quantitative Demographic Potential

2.3.5. Stage 5. Analysis of the Relationship between the Quantitative Demographic Potential and Real Growth (Natural Increse and Net Migration)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Theoretical Framework

3.1.1. Theory of Geographical Location

3.1.2. Theory of Urban Shrinkage

3.2. The Results of Empirical Research

- Diagnosing quantitative demographic potential is described by population size, population density, and population structure based on age and sex,

- The impact of natural increase and net migration on quantitative demographic potential,

- Identification of the relationship between the quantitative demographic potential level and the impact of natural increase and migration balance (real growth).

3.2.1. Diagnosing Quantitative Demographic Potential

3.2.2. The Impact of Natural Increase and Net Migration on Quantitative Demographic Potential

3.2.3. Identification of the Relationship between The Quantitative Demographic Potential Level and the Impact of Natural Increase and Migration Balance (Real Growth)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Group of Issues | Indicators | Character of Indicators | References | Information on Internet Statistical Databases for Germany, Poland and Lithuania | Choice of Indicators | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Number of population | described | [54,55] | available | rejected | |

| Population dynamics | described | [60] | available | accepted | ||

| Share of the region’s population in relation to the total area | described | [54] | available | rejected | ||

| Population distribution | Population density | described | [7,30,54] | available | accepted | |

| Population by age | Proportion of working age population in total population (%) | described | [14] | available | rejected | |

| Proportion of post-working age population in total population (%) | described | [56] | available | rejected | ||

| Proportion of population aged 65 and older in total population (%) | described | [54,55] | available | accepted | ||

| Ageing index | described | [56] | available | accepted | ||

| Population by sex | Femininity ratio at the age of 20–34 | described | [14] | unavailable | rejected | |

| Femininity ratio | described | [54,55] | available | accepted | ||

| Real growth | Natural increase | Live births per 1000 population | determined | [54,55] | available | rejected |

| Deaths per 1000 population | determined | [54,55] | available | rejected | ||

| Demographic dynamics ratio (divide the number of births into the number of deaths) | determined | [56] | available | rejected | ||

| Natural increase per 1000 population (average over the 3-year period) | determined | [7] | available | rejected | ||

| Natural increase per 1000 population | determined | [30,54,55,56] | available | accepted | ||

| Net migration | Net migration per 1000 population | determined | [14,30,54,55] | available | accepted | |

| Number of emigrants aged 20–39 in the total number of emigrants | determined | [60,61] | unavailable | rejected | ||

References

- Bußmann, A. Die Dezentrale Grenzüberschreitende Zusammenarbeit mit Deutschlands Nachbarländern Frankreich und Polen; Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2005; ISBN 978-3-8329-1229-1. [Google Scholar]

- Maretzke, S.; Porsche, L. (Eds.) Kleinstädte in ländlichen Räumen. Ein Spiegelbild ihrer ökonomischen, sozialen und siedlungsstrukturellen Rahmenbedingungen. In Das Neue Wachstum der Städte. Ist Schrumpfung jetzt Abgesagt? BBSR: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 36–55. ISBN 1868-0097. [Google Scholar]

- Porsche, L. Die Zukunft von Kleinstädten gestalten. Entwicklungsperspektiven für Kleinstädte eröffnen. Raum Plan. 2015, 181, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Jezierska-Thöle, A. Rozwój obszarów wiejskich Polski Północnej i Zachodniej oraz Niemiec Wschodnich; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika: Toruń, Poland, 2018; ISBN 978-83-231-3881-5. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, A. Nachhaltiges Suburbia?—Umdeutungen der Raumbezüge für Kleinstädte mit Leerstands phänomenen in der Nähe von ostdeutschen Wachstumskernen in der Peripherie am Beispiel des Saaletals. In Wohnungsleerstände in Deutschland; Schmidt, H., Vollmer, M., Eds.; Wüstenrotstiftung: Darmstadt, Germany, 2017; pp. 297–317. [Google Scholar]

- Dannenberg, P.; Lang, T.; Lehmann, K. Einführung “Ländliche Räume” in Deutschland: Neuere Zugänge zu einer alten Kategorie. Eur. Reg. 2012, 18, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kołodziejczyk, D. Ocena potencjału demograficznego gmin w Polsce (w aspekcie ilościowym i jakościowym). Studia Obsz. Wiej. 2002, 2, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sudra, P. Ocena potencjału demograficznego wybranych gmin położonych w rejonie węzłów autostrady A2. Człowiek Środowisko 2015, 39, 71–93. [Google Scholar]

- Morosanu, L. Professional bridges: Migrants’ ties with natives and occupational advancement. Sociol. J. Br. Sociol. Assoc. 2016, 50, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge Forschungszentrum. Wanderungsmonitoring: Erwerbsmigration nach Deutschland. Jahresbericht 2015; Migration, Integration und Asyl: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Siedentop, S.; Uphues, N. Ländliche Räume im Sog der Reurbanisierung? Befunde für Baden-Württemberg und raumordnungs-politische Schlussfolgerungen. In Reurbanisierung in Baden—Württembergischen Stadtregionen; Fricke, A., Siedentop, S., Zakrzewski, P., Eds.; Akademie für Raumforschung und Landesplanung: Hannover, Germany, 2015; pp. 187–203. [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer, H. Arbeitsmarkt: Arbeitsangebot und Arbeitsvolumen. In Perspektive 2035. Wirtschaftspolitik für Wachstum und Wohlstand in der alternden Gesellschaft; Institut der Deutschen Wirtschaft Köln: Köln, Germany, 2017; pp. 58–73. ISBN 978-3-602-14982-7. [Google Scholar]

- Parysek, J.J. Miasta polskie na przełomie XX i XXI wieku. Rozwój i przekształcenia strukturalne; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2005; ISBN 83-60247-08-0. [Google Scholar]

- Stanny, M. Przestrzenne zróżnicowanie rozwoju obszarów wiejskich w Polsce; Instytut Rozwoju Wsi i Rolnictwa Polskiej Akademii Nauk: Warszawa, Poland, 2013; ISBN 978-83-89900-53-1. [Google Scholar]

- Piracha, M.; Saraogi, A. Remittances and migration intentions of the left-behind. Migr. Dev. 2017, 6, 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharr, F.; Aumüller, A.; Barczyk, R.; Riedel, J.; Untiedt, G. Grenzüberschreitende Unternehmensaktivitäten in der sächsisch-polnischen Grenzregion: Gutachten im Auftrag des Bundesministeriums für Wirtschaft und Technologie, mit Unterstützung der Sächsischen Staatsregierung und der Europäischen Union; Ifo Institute—Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich: Monachium, Germany, 2001; ISBN 3-88512-391-6. [Google Scholar]

- Węcławowicz, G.; Degórski, M.; Komornicki, T.; Korzeń, J.; Bański, J.; Juliusz, K.; Soja, R.; Śleszyński, P.; Więckowski, M. Studia nad Przestrzennym Zagospodarowaniem Obszaru Wzdłuż Granicy Polsko-Niemieckiej (Studies on Spatial Development of the Polish-German Border Region); IGiPZ PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2006; ISBN 83-87954-86-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bański, J.; Dobrowolski, J.; Flaga, M.; Janicki, W.; Wesołowska, M. Wpływ Granicy Państwowej na Kierunki Rozwoju Społeczno-Gospodarczego Wschodniej Części Województwa Lubelskiego; PAN. IGiPZ: Warszawa, Poland, 2010; ISBN 978-83-62089-01-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gwiaździńska-Goraj, M. Przemiany cech demograficznych ludności w latach 1988–2009 i ich wpływ na peryferyzację obszarów wiejskich województwa warmińsko-mazurskiego. Studia Obsz. Wiej. 2011, 26, 153–174. [Google Scholar]

- Malkowski, A. Regiony przygraniczne jako terytoria peryferyjne na przykładzie wschodniego i zachodniego pogranicza. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2011, 221, 364–372. [Google Scholar]

- Miszczuk, A. Demograficzne uwarunkowania peryferyjności regionu (na przykładzie Polski Wschodniej). Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2011, 168, 472–484. [Google Scholar]

- Jezierska-Thöle, A.; Janzen, J. Przemiany demograficzne i gospodarki rolnej w wiejskiej strefie przygranicznej Niemiec i Polski. Acta Sci. Pol. Adm. Locorum 2012, 11, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Miszczuk, A.; Wesołowska, M. Demographic and settlement transformations in peripheral regions (based on the example of eastern Poland). Ann. UMCS Geogr. Geol. Mineral. Petrogr. 2012, 67, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gwiaździńska-Goraj, M.; Jezierska-Thöle, A. Peryferyjność obszarów wiejskich województwa warmińsko-mazurskiego a zmiany ludnościowe w latach 1988–2011. Studia Obsz. Wiej. 2013, 34, 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Hyll, W.; Schneider, L. Relative deprivation and migration preferences. Econ. Lett. 2014, 122, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlewicz, K.; Senetra, A.; Gwiazdzinska-Goraj, M.; Krupickaite, D. Differences in the environmental, social and economic development of Polish-Lithuanian trans-border regions. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 147, 1015–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rink, D.; Haase, A.; Bernt, M.; Arndt, T.; Ludwig, J. Urban Shrinkage in Leipzig, Germany; Department Urban and Environmental Sociology: Leipzig, Germany, 2011; p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- Pociūtė-Sereikienė, G.; Baranauskienė, V.; Daugirdas, V. Spatial exclusion in Lithuania: Peripheries as “losers”, metropolitan areas as “winners”. Prz. Geogr. 2019, 91, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pociūtė-Sereikienė, G.; Kriaučiūnas, E.; Ubarevičienė, R. Peripheralisation trends in rural territories: The case of Lithuania. Stagec 2014, 116, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosner, A. Zmiany Rozkładu Przestrzennego Zaludnienia Obszarów Wiejskich. Wiejskie Obszary Zmniejszające Zaludnienie i Koncentrujące Ludność Wiejską; Instytut Rozwoju Wsi i Rolnictwa Polskiej Akademii Nauk: Warszawa, Poland, 2012; ISBN 83-89900-48-3. [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, K. Obszary wiejskie i małe miasta: Czy lokalne centra są potrzebne współczesnej wsi? Studia Ekon. 2016, 279, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Maretzke, S. Demografischer Wandel im ländlichen Raum. So vielfältig wie der Raum, so verschieden die Entwicklung. Inf. Raumentwickl. 2016, 2, 169–187. [Google Scholar]

- Gans, P.; Siedentop, S. Editorial on the special issue “An international perspective on the processes, patterns, and outcomes of reurbanisation”. Comp. Popul. Stud. 2017, 42, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, A.; Herfert, G.; Kabisch, S.; Steinführer, A. Reurbanization in east German cities. disP Plan. Rev. 2010, 46, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetz, S. Besonderheiten in der Entwicklung kleiner Städte in ländlichen Räumen. In Kleine Städte in Peripheren Regionen. Prozesse—Teilhabe und Handlungsbefähigung—Integriertes Stadtentwicklungsmanagement; Engel, A., Harteisen, U., Kaschlik, A., Eds.; Dorothea Rohn: Detmold, Germany, 2012; pp. 45–66. ISBN 978-3-939486-68-8. [Google Scholar]

- Brombach, K.; Jessen, J.; Siedentop, S.; Zakrzewski, P. Demographic patterns of reurbanisation and housing in metropolitan regions in the US and Germany. Comp. Popul. Stud. 2017, 42, 281–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubarevičienė, R.; van Ham, M. Population decline in Lithuania: Who lives in declining regions and who leaves? Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2017, 4, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kazlauskiene, E.; Zitkiene, R.; Rakauskiene, O.; Ranceva, O. Demographics in quality of life assessment: Lithuania in EU context. KSI Trans. Knowl. Soc. 2014, 7, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ubarevičienė, R.; van Ham, M.; Burneika, D. Shrinking regions in a shrinking country: The geography of population decline in Lithuania 2001–2011. Urban Stud. Res. 2016, 2016. Available online: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/usr/2016/5395379/ (accessed on 2 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Fihel, A.; Okólski, M. Population decline in the post-communist countries of the European Union. Popul. Soc. 2019, 567, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thöle, M.; Jezierska-Thole, A. Life expectancy and mortality rates in Poland and Germany—A comparative analysis. In Proceedings of the 13th International Days of Statistics and Economics, Prague, Czechia, 5–7 September 2019; Loster, T., Pavelka, T., Eds.; 2019; pp. 1537–1547. [Google Scholar]

- Markiewicz, W. Przeobrażenia społeczne ziem zachodnich. In Ziemie Zachodnie w Granicach Macierzy; Wydawnictwo Poznańskie: Poznań, Poland, 1966; pp. 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, H.G. Die Bevölkerungsentwicklung in Deutschland im Zweiten Weltkrieg: Mit einem Überblick über die Entwicklung von 1945 bis 1990; Kulturstiftung der Deutschen Vertriebenen: Bonn, Germany, 1991; ISBN 978-3-88557-089-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lüderitz, J. Lagow im Lebuser Land und Umgebung: Ausflüge östlich der Oder; Bock Kuebler Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3-86155-115-7. [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowski, S. Nowa społeczność na ziemiach zachodnich. Nowe Drogi. 1960, 6, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Lithuania—Oficialiosios Statistikos Portalas. Available online: https://www.stat.gov.lt/en# (accessed on 31 March 2020).

- Weiß, W. Mecklenburg-Vorpommern: Brücke zum Norden und Tor zum Osten; mit einem Anhang Fakten—Zahlen —Übersichten; Klett-Perthes: Gotha, Germany, 1996; ISBN 978-3-623-00685-7. [Google Scholar]

- Weiß, W. Der Ländlichste Raum—Regional-demografische Perspektiven. Probleme von Abwanderungsgebieten mit geringer Bevölkerungsdichte. Landkreis 2002, 72, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bański, J. Współczesne typologie obszarów wiejskich w Polsce—Przegląd podejść metodologicznych. Przegląd Geogr. 2014, 86, 441–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostow, W.W. Theorists of Economic Growth from David Hume to the Present. With a Perspective on the Next Century; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-19-535979-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kondracki, J. Geografia Polski: Mezoregiony Fizyczno-Geograficzne; Wydaw. Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 1994; ISBN 978-83-01-16022-7. [Google Scholar]

- Maèiulyt, J.; Veteikis, D.; Sabanovas, S. Recomposition of rural space in Lithuania since the restoration of independence. Acta Sci. Pol. Adm. Locorum 2012, 11, 167–183. [Google Scholar]

- Senetra, A.; Szczepanska, A.; Veteikis, D.; Wasilewicz-Pszczolkowska, M.; Simanauskiene, R.; Volungevicius, J. Changes of the land use patterns in Polish and Lithuanian trans-border rural area. Baltica 2013, 26, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zdrojewski, E.Z. Podstawy Demografii; Wydaw. Uczelniane WSI: Koszalin, Poland, 1995; ISBN 83-86123-21-4. [Google Scholar]

- Szymańska, D.; Biegańska, J. Potencjał demograficzny. In Charakterystyka Obszarów Wiejskich w 2008 r.; Wydział Poligraficzny Urzędu Statystycznego w Olsztynie: Olsztyn, Poland, 2010; pp. 49–54. ISBN 978-83-88130-83-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner, A.; Stanny, M. Monitoring Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich. Etap 1. Przestrzenne Zróżnicowanie Poziomu Rozwoju Społeczno-Gospodarczego Obszarów Wiejskich w 2010 Roku; Fundacja Europejski Fundusz Rozwoju Wsi Polskiej; Instytut Rozwoju Wsi i Rolnictwa PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Prát, Š.; Bui, T.M. A Comparison of Ukrainian labor migration in the Czech Republic and Poland. East Eur. Politics Soc. 2018, 32, 767–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, C. International migration, the brain drain and poverty: A cross-country analysis. World Econ. 2009, 32, 1180–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, B.; Taylor, M.P. Differences in opportunities? Wage, employment and house-price effects on migration. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2012, 74, 831–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napierała, J. Regionalne aspekty zróżnicowania mobilności Polaków w świetle wyników sondażu. In Współczesne Migracje Zagraniczne Polaków. Aspekty Lokalne i Regionalne; Kaczmarczyk, P., Ed.; Ośrodek Badań nad Migracjami Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego: Warszawa, Poland, 2008; pp. 133–158. ISBN 978-83-923898-0-4. [Google Scholar]

- Szyszka, M. Zagraniczna migracja zarobkowa jedną ze strategii życiowych młodego pokolenia. Rocz. Nauk Społecznych 2016, 8, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gałka, J. Wpływ permanentnych migracji zagranicznych na zmiany regionalnych układów zaludnienia w Polsce. Studia Ekon. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Katowicach 2017, 309, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, W.C.; Scherbov, S. The characteristics approach to the measurement of population aging. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2013, 39, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Polakowski, M.; Szelewa, D. Poland in the migration chain: Causes and consequences. Transf. Eur. Rev. Labour Res. 2016, 22, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocki, F. Metody Taksonomiczne w Rozpoznawaniu Typów Ekonomicznych Rolnictwa i Obszarów Wiejskich; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2010; ISBN 978-83-7160-583-3. [Google Scholar]

- Malina, A.; Zeliaś, A. Taksonomiczna analiza przestrzennego zróżnicowania jakości życia ludności w Polsce w 1994 r. Przegląd Stat. 1997, 44, 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kukuła, K. Metoda unitaryzacji zerowanej na tle metod normowania cech diagnostycznych. Acta Sci. Acad. Ostroviensis 1999, 4, 5–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bąk, I.; Wawrzyniak, K.; Oesterreich, M. The application of statistical methods to identify factors determining employment effectiveness in district labour offices in Poland. Acta Univ. Lodz. Folia Oeconomica 2019, 4, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fura, B.; Wang, Q. The level of socioeconomic development of EU countries and the state of ISO 14001 certification. Qual. Quant. 2017, 51, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Webb, J.W. Ruch naturalny i migracyjny jako składnik przemian ludnościowych. Przegląd Zagr. Lit. Geogr. 1964, 1, 134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Gwiaździńska-Goraj, M.; Goraj, S. Transformation of Demographic Characteristics of the Rural Population of the Warmia and Mazury Voivodship; University of Economics in Prague: Prague, Czechia, 2015; Volume 34, pp. 498–510. [Google Scholar]

- Biały, S.; Długosz, Z. Typologia demograficzna krajów Europy wg Webba w latach 2005–2025. Kult. Polityka 2015, 18, 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Serafin, P. Zmiany w typologii demograficznej miejskich obszarów funkcjonalnych Polski w latach 2002–2017. Biul. Kom. Przestrz. Zagospod. Kraj. PAN 2018, 272, 328–343. [Google Scholar]

- Serafin, P. Zmiany w potencjale demograficznym ludności wiejskiej w województwie małopolskim w latach 1996–2006. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Krakowie 2010, 821, 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney, P.; Errington, A. The role of small towns in the local economy and some implications for development policy. Local Econ. 2000, 15, 280–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettlinger, N. Cultural economic geography and a relational and microspace approach to trusts, rationalities, networks, and change in collaborative workplaces. J. Econ. Geogr. 2003, 3, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, H.H. Ragnar Nurkse’s development theory: Influences and perceptions. In Ragnar Nurkse (1907–2007): Classical Development Economics and its Relevance for Today; Reinert, E., Kregel, J., Kattel, R., Eds.; Anthem Press: London, UK, 2009; pp. 183–202. ISBN 978-1-84331-819-4. [Google Scholar]

- Churski, P.; Stryjakiewicz, T. New experiences of Polish regional policy in the first years of membership in the European Union. Quaest. Geogr. 2006, 25, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Stryjakiewicz, T.; Ciesiółka, P.; Jaroszewska, E. Urban shrinkage and the post-socialist transformation: The case of Poland. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryjakiewicz, T.; Jaroszewska, E.; Marcińczak, S.; Ogrodowczyk, A.; Rumpel, P.; Siwek, T.; Slach, O. Współczesny kontekst i podstawy teoretyczno-metodologiczne analizy procesu kurczenia się miast. In Kurczenie się Miast w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej; Stryjakiewicz, T., Ed.; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2014; pp. 9–14. ISBN 978-83-7986-024-1. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, B.; Biedermann, R. Urban brownfields as temporary habitats: Driving forces for the diversity of phytophagous insects. Ecography 2006, 29, 928–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salone, C.; Besana, A. Urban shrinkage. Theoretical reflections and empirical evidence from a Southern European perspective. In Proceedings of the AESOP-ACSP Joint Congress, Dublin, Ireland, 15–19 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hospers, G.J. Policy responses to Urban shrinkage: From growth thinking to civic engagement. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 1507–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Poland—Local Data Bank. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/BDL/ (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Federal Statistical Office Germany. Available online: http://www.destatist.de (accessed on 31 March 2020).

- Lammers, K.; Niebuhr, A.; Polkowski, A.; Stiller, S.; Hildebrandt, A.; Nowicki, M.; Susmarski, P.; Tarkowski, M. Polsko-Niemiecki Obszar Przygraniczny w Roku 2020—Scenariusz Rozwoju i Zalecenia Odnośnie Jego Realizacji; Hamburgisches Welt-Wirtschafts-Archiv (HWWA) (Hamburg Institute of International Economics): Gdańsk, Poland, 2006; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Borella, S. Migrationspolitik in Deutschland und der Europäischen Union. Eine Konstitutionenökonomische Analyse der Wanderung von Arbeitskräften; 1st Ed.; Mohr Siebeck: Tübingen, Germany, 2008; ISBN 978-3-16-149645-5. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowska-Lusińska, I.; Okólski, M. Migracja z Polski po 1 Maja 2004 r: Jej Intensywność i Kierunki Geograficzne oraz Alokacja Migrantów na Rynkach Pracy Krajów Unii Europejskie; University of Warsaw, Centre of Migration Research (CMR): Warszawa, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lesińska, M.; Okólski, M.; Slany, K.; Solga, B. Dekada Członkostwa Polski w UE. Społeczne Skutki Emigracji Polaków po 2004 Roku; Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego: Warszawa, Poland, 2014; ISBN 978-83-235-1611-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sipavičienė, A.; Stankuniene, V. The social and economic impact of emigration on Lithuania. In Coping with Emigration in Baltic and East European Countries; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 45–64. ISBN 978-92-64-20491-1. [Google Scholar]

- Godlewska, J. Migracje i Imigranci w Polsce–Skala, Podstawy Prawne, Polityka. Ekspertyza Przygotowana w Ramach Projektu “EAPN Polska—Razem na rzecz Europy Socjalnej”; Fundusz Inicjatyw Obywatelskich: Rybnik, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ranceva, O.; Rakauskienė, O. Threat of emigration for the socio-economic development of Lithuania. Bus. Manag. Educ. 2013, 11, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Bilan, Y.; Jasinskas, E.; Griksaite, R. Migration trends in Lithuania and other new EU member states. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2016, 15, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Musiał-Malago’, M. Kurczenie się miast Polski—Analiza i pomiar zjawiska. Rozw. Reg. Polityka Reg. 2018, 42, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

| Term | Definition | Total Number | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study area | Combined data for Polish–German and Polish–Lithuanian transborder regions | 2 | |||||||

| Transborder regions | Combined data for the areas situated on both sides of the Polish–German border, i.e., the Polish–German transborder region, internal EU border (A) | Combined data for the areas situated on both sides of the Polish–Lithuanian border, i.e., the Polish–Lithuanian transborder region, external EU border (B) | 2 | ||||||

| NUTS 0 | Average data at country level—Germany | Average data at country level—Poland | Average data at country level—Lithuania | 3 | |||||

| Border regions | Border region in Germany | Border region in western Poland | Border region in eastern Poland | Border region in Lithuania | 4 | ||||

| Combined data for NUTS 2 units (states): —Brandenburg, —Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | Combined data for NUTS 2 units (voivodeships): —West Pomerania, —Lubuskie | Combined data for NUTS 2 units (voivodeships): —Warmia and Mazury —Podlasie | Combined data for NUTS 2 units (counties): —Alytus —Marijampolė | 8 | |||||

| LAU 1 | T | 26 | T | 35 | T | 38 | T | 10 | 109 |

| U | 2 | U | 5 | U | 5 | U | 1 | 13 | |

| R | 24 | R | 30 | R | 33 | R | 9 | 96 | |

| Indicator | Name | Description | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative demographic potential is described by indicators: | |||

| x1 | Population density | Population per unit area (1 km2). | Stimulant |

| x2 | Population dynamics | Changes in the population of Poland and Germany between 2007 and 2017 (as of 31 December 2017) and the population of Lithuania between 2008 and 2018 (as of 1 January 2018). The baseline value (for 2007 and 2008) was set at 100 points, and the values for 2017 and 2018 were calculated relative to the baseline value. Values below 100 are indicative of population decrease, whereas values above 100 are indicative of population increase in the analyzed period. | Stimulant |

| x3 | Proportion of population aged 65 and older in total population (%) | Percentage of the population aged 65 years and older in total population. This is the main indicator of population ageing. | Destimulant |

| x4 | Ageing index | Ratio of the population aged 65 and older to the population aged 0 to 14 * × 100. This indicator provides information about the future potential of young people relevant to seniors. | Destimulant |

| x5 | Femininity ratio | Number of women per 100 men in a given area, which provides information about the reproductive potential of a population | Stimulant |

| Quantitative demographic potential is determined by indicators: | |||

| x6 | Natural increase per 1000 population | The difference between the number of live births and the number of deaths in a given area per 1000 population | Stimulant |

| x7 | Net migration per 1000 population | The difference between the inflow and outflow of people to a given area per 1000 population | Stimulant |

| Class | Identification Criteria | Quantitative Demographic Potential |

|---|---|---|

| I | high | |

| II | moderately high | |

| III | moderately low | |

| IV | low |

| Category | Real Growth | NI—NM relation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population growth (PG+) | |||

| A | PG+ | +NI > −NM | Positive natural increase exceeds negative net migration |

| B | +NI > +NM | Positive net migration and even higher positive natural increase | |

| C | +NI < +NM | Positive natural increase and even higher positive net migration | |

| D | −NI < +NM | Positive net migration compensates for negative natural increase | |

| Population decline (PG−) | |||

| E | PG− | −NI > +NM | Negative natural increase is not compensated by positive net migration |

| F | −NI > −NM | Negative net migration and even higher negative natural increase | |

| G | −NI < −NM | Negative natural increase and even higher negative net migration | |

| H | +NI < −NM | Negative net migration is not compensated by positive natural increase | |

| Specification | Germany | Poland | Lithuanian | Polish–German and Polish–Lithuanian Transborder Regions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Areas Situated on both Sides of the Polish–German Border, i.e., the Polish–German Transborder Region, Internal EU Border (A) | Areas Situated on both Sides of the Polish–Lithuanian Border, i.e., the Polish–Lithuanian Transborder Region, External EU Border (B) | ||||||||

| Total | Border Region in Germany | Border Region in Western Poland | Total | Border Region in Eastern Poland | Border Region in Lithuania | |||||

| Population density | 231 | 123 | 43 | 60 | 75 | 77 | 74 | 44 | 59 | 29 |

| Population dynamics | 101 | 101 | 83 | 94 | 99 | 97 | 101 | 89 | 100 | 78 |

| Ageing index | 159 | 106 | 131 | 138 | 147 | 188 | 105 | 129 | 102 | 157 |

| Femininity ratio | 103 | 107 | 117 | 106 | 104 | 103 | 106 | 109 | 105 | 113 |

| Class | Polish–German and Polish–Lithuanian Transborder Regions | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Areas Situated on both Sides of the Polish–German Border, i.e., the Polish–German Transborder Region, Internal EU Border (A) | Areas Situated on both Sides of the Polish–Lithuanian Border, i.e., the Polish–Lithuanian Transborder Region, External EU Border (B) | |||||||||||||

| Total | Border Regions in Germany | Border Regions in Western Poland | Total | Border Regions in Eastern Poland | Border Regions in Lithuania | ||||||||||

| number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | ||

| I | Pd ≥ 0.2270 | 12 | 11.0 | 6 | 9.8 | 1 | 3.8 | 5 | 14.3 | 6 | 12.5 | 6 | 15.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| II | 0.1198 ≤ Pd < 0.2270 | 55 | 50.5 | 31 | 50.8 | 2 | 7.7 | 29 | 82.9 | 24 | 50.0 | 22 | 57.9 | 2 | 20.0 |

| III | 0.0125 ≤ Pd < 0.1198 | 24 | 22.0 | 12 | 19.7 | 11 | 42.3 | 1 | 2.9 | 12 | 25.0 | 9 | 23.7 | 3 | 30.0 |

| IV | Pd < 0.0125 | 18 | 16.5 | 12 | 19.7 | 12 | 46.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 12.5 | 1 | 2.6 | 5 | 50.0 |

| Total | 109 | 100.0 | 61 | 100.0 | 26 | 100.0 | 35 | 100.0 | 48 | 100.0 | 38 | 100.0 | 10 | 100.0 | |

| Specification | Germany | Poland | Lithuanian | Polish–German and Polish–Lithuanian Transborder Regions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Areas Situated on both Sides of the Polish–German Border, i.e., the Polish–German Transborder Region, Internal EU Border (A) | Areas Situated on both Sides of the Polish–Lithuanian Border, i.e., the Polish–Lithuanian Transborder Region, External EU Border (B) | ||||||||

| Total | Border Region in Germany | Border Region in Western Poland | Total | Border Region in Eastern Poland | Border Region in Lithuania | |||||

| Natural increase per 1000 population | −1.78 | −0.02 | −4.07 | −3.2 | −2.6 | −4.7 | −0.4 | −3.8 | −0.2 | −7.5 |

| Net migration per 1000 population | 5.03 | 0.04 | −1.17 | 0.1 | 2.9 | 6.7 | −0.8 | −2.8 | −1.7 | −3.8 |

| Type | Polish–German and Polish–Lithuanian Transborder Regions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Areas Situated on both Sides of the Polish–German Border, i.e., the Polish–German Transborder Region, Internal EU Border (A) | Areas Situated on both Sides of the Polish–Lithuanian Border, i.e., the Polish–Lithuanian Transborder Region, External EU Border (B) | |||||

| Total | Border Region in Germany | Border Region in Western Poland | Total | Border Region in Eastern Poland | Border Region in Lithuania | ||

| A | 6 | 1 | - | 1 | 5 | 5 | - |

| B | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - |

| C | 8 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 | - |

| D | 16 | 16 | 15 | 1 | - | - | - |

| E | 10 | 10 | 8 | 2 | - | - | - |

| F | 15 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 7 | 5 |

| G | 39 | 20 | - | 20 | 19 | 14 | 5 |

| H | 14 | 4 | - | 4 | 10 | 10 | - |

| Total | 109 | 61 | 26 | 35 | 48 | 38 | 10 |

| Parameter | Demographic Categories Based on Webb’s Typology | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | |||

| Quantitative demographic potential (classes) | I | 5 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 12 |

| II | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 30 | 13 | 55 | |

| III | 0 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 24 | |

| IV | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 18 | |

| Total | 6 | 1 | 8 | 16 | 10 | 15 | 39 | 14 | 109 | |

| Parameter | Natural Increase Per 1000 Population | Net Migration Per 1000 Population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Value | |||

| Quantitative demographic potential of LAU 1 units (classes) | I | 1.3 | 3.2 |

| II | −0.8 | −2.6 | |

| III | −3.9 | 0.8 | |

| IV | −7.7 | −0.2 | |

| Average for the study area | −2.4 | −0.8 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gwiaździńska-Goraj, M.; Pawlewicz, K.; Jezierska-Thöle, A. Differences in the Quantitative Demographic Potential—A Comparative Study of Polish–German and Polish–Lithuanian Transborder Regions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229414

Gwiaździńska-Goraj M, Pawlewicz K, Jezierska-Thöle A. Differences in the Quantitative Demographic Potential—A Comparative Study of Polish–German and Polish–Lithuanian Transborder Regions. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229414

Chicago/Turabian StyleGwiaździńska-Goraj, Marta, Katarzyna Pawlewicz, and Aleksandra Jezierska-Thöle. 2020. "Differences in the Quantitative Demographic Potential—A Comparative Study of Polish–German and Polish–Lithuanian Transborder Regions" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229414