Abstract

Historical parks, as an inseparable element of manors and landowners’ palaces, constitute a valuable cultural heritage, commemorating the times of the Polish nobility. From among the 16,000 manor houses existing before 1939, only 3433 objects remained, including 1965 of them are residential parks without the dominant feature in the form of a building. Numerous studies and activities are carried out to protect, restore, maintain and adapt these facilities to current needs. They are general, often theoretical, or individual concern objects, or only mansions or palaces, excluding parks, which makes it difficult to assess the problem objectively. The aim of this study is a comprehensive assessment of the distribution (in terms of spatial, social and administrative terms), the state of preservation (in terms of area size, technical, phytosanitary and original composition) and the use of the potential of historical parks in manor or palace complexes. The authors examined the distribution of these objects using relative indicators and descriptive statistics. The economic potential of the parks was explored in comparison to the facilities based on their sale offers, using the analysis of variance and the Tukey test. The results show the detailed distribution, state of preservation and problems related to the current and potential use of post-manor parks, manor and palace parks in 16 voivodeships of the country.

1. Introduction

Manor-house parks and palace-park complexes established during the feudal period are an essential spatial, historical and cultural element of rural areas in Poland, as well as in other European countries. In the 17th Century, the nobility or magnates inhabiting these estates constituted as much as 10% of Poland population. It was more than in any other country of the time in Europe, with an average share of 3–4% of the noble class [1]. Additionally, Polish law (3 May Constitution of 1791) did not divide into a higher and a lower class within the nobility, unlike many European countries. Thus, the manors were owned by both the farm nobility and the magnates. There were about 200 magnate families with estates occupying an area of 3000–14,000 ha. Throughout the entire period of the First Republic—Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (i.e., until the third partition of Poland in 1795)—the largest and best organized noble estates belonged to large families. These were the largest agricultural producers, processors and significant exporters. The homestead nobility owned farms with an area of less than 50 ha [1,2]. The average size of land estates in Poland in 1921 was 600 ha [2], while already by 1939, had fallen to about 400 ha [1].

In Europe since the French Revolution, the slow decline of the English (or French) country house coincided with the rise not just of taxation, but also of modern industry, along with the agricultural depression at the end of the 19th Century. The period of two world wars in the first half of the 20th Century was particularly severe for landowners’ estates [3]. In the interwar period (the Second Polish Republic), the number of the Polish landed gentry amounted to 0.36% of the population [2].

After the Second World War, manors in France or England often remained in the hands of their owners or returned to them. It happened, however, that for economic reasons (high maintenance costs of such facilities) they were transferred by the owners to the state. A total of 1990 English country houses have been demolished, severely reduced in size or are ruined [4].

Meanwhile, in Poland, as well as in Belarus, Lithuania and Ukraine (the countries which included the former Polish eastern borderlands after the war), the Soviet Union imposed communism. As a result, in the present and former Polish territories, the new communist authorities took away manors from their rightful owners, hailed as enemies of the working class. On 20 July 1944, the so-called “Polish National Liberation Committee” (PKWN) was established in Moscow as a temporary authority in Poland after World War II. On 6 September 1944, PKWN issued a “Decree on Agricultural Reform”, based on which the estates (land, crops, flocks, but also all equipment, including works of art, furniture, books, etc.) of all landowners in Poland were deprived without compensation. In total, between 1944 and 1947, about 14,000 landed gentry estates were seized, of which 10,000 in areas within Poland’s postwar borders, covering 3.5 M ha and agricultural land was parceled out. Additionally, there were about 4000 estates in the Eastern Borderlands, covering 2.0 M ha. Most of the land was taken over by the state, creating State Collective Farms (PGR). Some of the landed property was parceled out among peasants. Each farmer received approx. 3 hectares of land [1,5]. This complicated history caused the manor and park complexes to constitute a national heritage which must be saved from oblivion.

1.1. The Historical Form and Role of the Manor-House Parks and Palace-Park Ensembles

Many researchers (including art historians, architects, sociologists and ethnographers) have studied the history of manor, palace and garden complexes. There are also monographic studies describing the history, composition, status of preservation of specific palace or manor/palace-garden ensemble. Already after the Second World War, this course was initiated by A. Szyszko-Bohusz, and in the broader scope, by Gerard Ciołek, thanks to whom numerous studies of historic gardens were created [6]. In the following years, J. Bogdanowski [7], Plapis and Majdecki continued his work [8].

Detailed descriptions of manors and studies on specific objects were created. Most of these objects were built during the 18th Century in the Baroque, and later Neoclassical, style with a characteristic two- or four-column portico on the axis of the front façade. Usually, landlords settled their estates on small hills, near a church, sometimes lake or river or, less frequently, near a forest which they later transformed into a park. The aim was a picturesque setting with a view of the entire countryside [6,9,10]. Countryside residences: manors and palaces were inhabited on average by seven to eight people per one place. It consisted of a three-generation family and residents, also most often from the family. There have been many studies describing the specificity of the composition and management of manor parks, analyzing the selection of plants and garden equipment. The specificity of the manor house was determined by the way it was developed, the relation of the ornamental part of the garden to the usable part and the presence of such elements as watercourses and reservoirs, varied terrain, etc. [6,9,11].

The primary purpose of the landed estates was agricultural production, but they were also local centers of patriotism and culture. Some landowners established schools and nurseries in the countryside, organized libraries and farmers’ clubs. They raised the level of farming through the establishment of horticultural schools and even created dendrological collections (e.g., in Waplewo Wielkie—art collections, library; in Rogalin—art collection, library; in Medica—horticultural school and dendrological collection) [12].

If the park was public, it was used by servants with their families and (less often) by poor children from the village. In times of peace, heiresses organized summer camps and day camps for children on their property. They set up a group of rural housewives, where peasants learned how to prepare sandwiches and tasty dishes, how to maintain hygiene and health, how to handle flowerbeds and how to arrange bouquets in vases. They also founded elementary schools [12,13,14].

Scientific research devoted to the historical documentation of historic manor and palace-parks complexes constitute the largest group of studies. Researchers analyze both individual objects [15] and make collective assessments or comparisons of them [16,17].

1.2. The Problem of Protection and Revalorization of the Historic Park, Palace and Manor Ensembles

The vast majority of publications concern the problem of the revalorization of specific objects [18,19] or their adaptation for contemporary purposes [20,21]. Many studies are devoted to the manor and palace buildings themselves. They concentrate on problems with their renovation and reconstruction, concerning a specific style is emphasized, as these buildings have been rebuilt or extended throughout history [22]. Researchers pay attention to threats to historic parks in the process of their revalorization [23].

After the liberation of Poland by the Soviet “Red Army” in 1944, the historic parks lost their functions and were neglected. They were taken over by State Collective Farms (PGR), production cooperatives or various types of social enterprises. Over time, the attitude towards parks has somewhat improved. Some of the administrators tried to take care of parks making some parts of the park were rearranged and introducing new plantings, often unskillfully, hence some of the objects were gradually losing their original composition [9,24].

In the 1960s, the Culture Center, aware of the fate of many valuable garden layouts, started to protect the parks from scratch. A survey conducted by the Board of Museums and Monuments Protection (pol. ZMiOZ) in the years 1957–1958 among park users brought approximate data from over 2000 objects, concerning the use of their area, the quality of the tree stand, equipment and state of preservation. In 1969, the ZMiOZ records included about 4000 park facilities, 60% of which without further data. Currently, the total number of parks amounts to 6000 [9].

From the mid-1970s, this issue was dealt with by the Palace-Garden Board for the Protection and Conservation, which later became the Historic Landscape Protection Center. This institution did not only popularize the principles of conservation proceedings through its design activity but was also a consultative body, assessing the correctness of the procedure and design documentation [25]. Thanks to the cooperation with numerous entities, including the State Council for Nature Conservation, nature conservators, the Ministry of Forestry and District Directorates of the State Forests, the Ministry of Municipal Economy and users, it has been possible in many cases to secure a valuable object. During the 25 post-war years, the Board of Museums and Monuments Protection financed works on the renovation of the most valuable historic parks, such as Wilanów, Nieborow, Arkadia, Radziejowice [15], Łańcut, Mogilany etc. [9,25].

Since 1965, doctrinal documents on cultural heritage have been developed within the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). It advises UNESCO, among others, on the entry of objects on the World Heritage List. A significant group of documents created by ICOMOS are programs and standards for the entire heritage or a selected area. They contain the description of the subject (definitions), goals and principles of conservation activities. The Polish National Committee of ICOMOS issued the Vade Mecum of the Monument Conservator [26].

Concerning the discussed issues of monument protection, the most important seems to be: The Act of 23 July 2003 on the protection and care of monuments [27] and the International Charter of Historical Gardens, the so-called Florence Charter, developed in 1981. This Charter complements the Venice Charter (1964) and contains guidelines that take into account the specificity of the protection of historic gardens [28,29].

Today, the National Heritage Institute (NID) is the legal successor of the Monuments Documentation Center, established in 1962. It continues the idea of protecting and sharing a cultural heritage with a broad audience. In 2002, the National Monument Research and Documentation Center (KOBiDZ) was established. Historical analysis of the buildings began successively. Huge material was collected and documented; the first registers of historic gardens in Poland and lists of their creators were developed. On this basis, the research of scientists and specialists has developed, which has allowed them to recreate the general picture of parks’ resources, their composition and a plant species structure. This process continues today by many landscape architects and historians [30].

1.3. Manor and Palace Parks Today—Their Condition, Function, Value and Potential

Compared to 16,000 manor and palace parks before 1939, little more than 3000 of them have survived today. Many of them stand empty [12]. Nevertheless, in Poland, we still have many mansions compared to England, where during the sewing period of the mid-19th Century there were only 5000 such mansions. The current number of preserved manors in England is 3000, which is similar to our country [4,31].

Maintaining the manors in their original function is very expensive. In England, the problem was solved in 1976 with the Finance Act—legislation that allowed landlords to apply for an inheritance tax exemption in exchange for a commitment to keep their homes open and well-kept. Houses that survived have become hotels, schools, hospitals, museums and prisons. The ownership or management of some places has been transferred to a private trust. Other houses have transferred artworks and furnishings under the Acceptance in Lieu scheme to property rights by various national or local museums. The possession or management of some of the places has been delegated to a private trust. Other houses have transferred works of art and furniture under the Acceptance in Lieu program to various national or local museums. This enables the former owners to withhold the tax.

Additionally, an increasing number of country houses are licensed for weddings and civil ceremonies. Another source of income is the use of the home as a venue, film and corporate entertainment venue. Many country houses are open to the public, although they remain inhabited by private houses [31,32].

Poland, being a member of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), has developed a similar system of monument protection and principles of financing heritage protection as in many European countries (Monument Protection System). The main form of monument protection is their legal protection through entry into the register (England, Poland, Lithuania) or to the list (France, the Netherlands). Responsibility for the condition of historic buildings rests primarily with their owners, the state and local authorities (Germany, Poland, Norway). Responsibility for the protection of monuments in Sweden or Germany rests with all citizens. The protection of cultural heritage objects owned by state institutions is financed from the state budget. Individual states provide financial assistance to owners in the proper maintenance of monuments and the necessary conservation works, mainly through a system of grant reimbursement costs. In some countries, granting financial support is conditional on the monument being made available to the public in part or whole (England, France). In Sweden, most of the costs of protection and conservation of monuments are covered by the private sector [33].

In Poland, the National Heritage Institute (NID) and KOBiDZ report the state of preservation of manor and palace parks [34]. NID Institute publishes guides for municipalities to develop a care program for monuments [35]. It presents a list of acceptable practices in the field of restoration and adaptation of monuments for present utility purposes [36].

According to Rydel, Polish manors have been changed to schools, rural health centers, social welfare homes or homes for random tenants. The status of most of them can be called poor, but not hopeless. Few of them still have historical elements of interiors: stoves, fireplaces, woodwork [10,12].

Some authors emphasize the role of historical objects in creating the national and territorial identity of societies through the testimony of past events. At the same time, they can be an essential factor in the social and economic development of a given region [37], influencing its tourist attractiveness [38] and stimulating the local economy [39].

According to the NID [35], cultural heritage is assigned different values:

- fundamental, i.e., scientific, historical, artistic;

- other, i.e., aesthetic, social, educational, cultural and economic.

Present-day functions and the state of preservation of historical parks are also under investigation. The deteriorating condition of these objects dates back to the beginning of the 1970s. From this point, the recording and evaluation of the behavior and functions of parks begin. The unsatisfactory state of the parks and manor complexes was written, among others, by Dombrowicz [40]. The author attempted to evaluate the economic value of parks, which he expressed as the value of restoring plants, including trees. Pay attention to the use of the potential of utility properties, including the use of the park for recreational functions, as well as educational (dendrological and genre collections) and cultural and historical functions. Recently, the number of studies on the adaptation of historic buildings to service and hotel facilities has grown [40,41].

Marek W. Kozak [42] presented an analysis of the state of manors, their distribution and the possibility of using heritage resources in the socio-economic and economic development. This topic is not widely researched. According to the author, there is a need for a serious discussion on the possibilities of using cultural heritage for economic and social development. It should be supported not only by theory but also by the practice of other countries. The author emphasized the possibility of using external funds and structural funds for the renovation, revitalization and promotion of such facilities. The scale of expenditure, however, is disproportionate to both the needs and the possibilities offered by using our heritage to promote the country and its economic activation. [42].

More and more works raise the importance of broadly understood culture for shaping social capital [43]. In the 20th Century, the importance of culture in social life was noticed and the interest in the extremely dynamic development of tourism, especially one oriented in learning about cultural heritage [44]. Usage of the tourist potential in park and manor complexes does not always bring positive results. Research on the use of castles in Lesser Poland Voivodeship shows that although half of them serve tourist purposes and influence local development. The level of their tourism development is nowhere near satisfying [44,45,46].

According to Legutko et al. [47], they may constitute a potential in the development of the local economy (e.g., as a tourist potential, creating a place brand, stimulating entrepreneurial activities based on heritage resources, or the growth of the real estate market). It is also visible in the development of the local community (by building and strengthening social capital, media interest, making the identity of the place, improving the spatial order and image of the commune). They can increase the natural potential (by increasing biodiversity, the presence of protected species, enhancing the landscape values of the site).

Murzyn-Krupisz [48] focused on the economic potential of cultural goods. The author distinguished use values (direct and indirect) and non-use values (including optional qualities, existence and legacy). Immediate use values are most often expressed by price, e.g., entrance fee to a facility, value of a historic property, costs of access to the facility or profits from the provision of services in the facility, such as the sale of souvenirs, consumption, etc.). Intermediate values are more challenging to estimate, but have significant social significance, as they relate to the functionality of a cultural good, its cognitive, educational and functional values. The “optional” nonuse value is associated with the possibility of benefiting from the facility in the future. The value of “being” relates to artistic, spiritual and cultural benefits. In turn, “heritage” means the symbolic and historical significance of a historic building and the possibility of its preservation as a cultural heritage for future generations.

The natural potential of historical parks is the least discussed. Mainly due to the preserved old trees, the naturalistic significance of such places is investigated. The dendroflora of parks is evaluated in terms of increasing biodiversity. Specific sites are used to diagnose bird habitats, protected species of plants and animals, including fungi, insects (e.g., hermit beetle) and lichens [49].

Researchers relatively rarely deal with the economic problem of reconstruction and valuation of manors [50,51,52]. Rosłon-Szeryńska et al. [50] argue that the price of historical land property is influenced by, among others, location, building size, plot area and degree of preservation of the building. Valuation parks in manor houses are problematic and often marginalized.

In Poland, in addition to the basic sources of financing, which are public funds from the state budget and local authorities budgets (at the level of the province, county or municipality), the financing of monument protection is also carried out with a significant share of funds from the EU and the Financial Mechanism of the European Economic Area. In terms of funds from the European Union, these are primarily structural funds distributed by regional operational programs (ROP). As a standard, the subsidy is granted in the amount of up to 50% of the expenditure necessary to perform the above-mentioned activities. However, the amount of the subsidy may be increased even up to 100% of the required spending, if, by art. 78 of the Act of 23 July 2003 [27], the monument has exceptional historical, artistic or scientific value, requires comprehensive conservation, restoration or construction works, or the state of preservation of the monument requires immediate restoration, restoration or construction works.

The data provided by Pieczonka et al. [33] on investments in 2007–2013 also shows that the maximum share of EU funds in eligible expenditure for projects aimed at the protection of cultural heritage in individual voivodeships ranged: from 70% (Pomerania, Lower Silesia) to 97% (Masovia, Greater Poland), and most often 85% (Opole, Warmia-Masuria, Podlaskie, Świętokrzyskie, West Pomerania, Lodzkie, Kuyavia-Pomerania, Silesia, Lesser Poland, Lublin).

In the study prepared by the National Heritage Board of Poland [53] on the protection of cultural heritage in the country, the results of a public opinion poll on monuments were presented. The opinion of the inhabitants of towns and villages was examined. The respondents were asked about their holiday preferences. In total, 37% of rural residents and 46% of urban residents indicated visiting historic palaces and castles. Rural residents visit monuments less often than city dwellers. The willingness to visit the historic park was suggested by 21% of rural residents and 34% of urban residents. Among the attractions that should accompany cultural heritage sites, exhibitions were mentioned (50%), concerts (36%), festivals (33%), shows (29%) and less frequently restaurants (19%). Interestingly, the public is aware that one can earn money on a monument. A total of 86% of the respondents answered like this and were aware that the reconstruction of a monument might harm its historical value (76%).

1.4. The Research Problem and the Purpose of This Work

The main goal of the research is to organize the knowledge about the concentration, state of preservation and potential of historical parks in Polish rural areas. Based on a critical analysis of the state of research, specific objectives were established in the form of information questions and hypotheses. The subject of the study is three types of objects: manor parks, palace parks and a park that is remnant of a former manor or palace complex.

According to the NID Reports [34,54] and other specialist’s studies [12,23,24], the state of the park-manor house and palace complexes is undergoing. Researchers do not study the differences in park management in individual voivodeships. There are generalizing opinions about the state of conservation and quantity of these objects in given regions, but an arbitrary comparative scale of these objects is not used. There is no comprehensive study on manor/palace parks located in rural areas of a collective and comparative nature throughout the country. A research question was formulated, what is the intensity of the occurrence of historical parks in a given province and is their number noticeable in the area of rural communes? Is their concentration in the area of the province optimal, so that they constitute a tourist potential while protecting them?

Unfortunately, in Poland, despite the formally existing monument management system, including the developed programs for the care of monuments at the national, voivodeship or municipal level, the number of this cultural heritage falling into ruin is growing every year. The question is, are the historical parks in fact in poor condition? In what way (spatial, historical and compositional, or technical and sanitary) have they been best preserved?

A lot of theoretical studies have been prepared covering the principles and problems of revalorization of historical parks, their potential and importance for society [23,28,29,34,35,36,42,47,48].

However, these data are not detailed and complete enough. Many types of research are case studies limited to one or several objects, which does not allow for a comprehensive analysis of the problem of managing historical parks in rural areas and the practical use of their potential. Therefore, the authors of this work posed the following research questions: How are historical parks in Poland managed? What are their functions and are their potential used? Is there a relationship with the management of the object and its condition of preservation?

One of the criteria for the valorization of cultural monuments is their assessment of their economic potential based on the market value of the property. There is a lack of comprehensive studies based on the financial profitability of investments, taking into account the current needs of users [50,51]. In practice, it happens that revalorized or adapted objects do not meet the assumed expectations and their historical value decreases. The detailed aim of this study is to check whether the value of parks concerning buildings is underestimated, which may harm their condition, rank and role in the rural space. A thesis has been made that the importance of parks is often marginalized in relation to buildings in the manor or palace complexes. The following directional research hypotheses were assumed, based on the above premises:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The price of the palace/manor and park complex largely depends on a) the state of preservation and b) the area of the building.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The state of the park does not have a significant impact on the market price of the palace/manor and park complex.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The larger the park area, the greater its impact on the price of the palace/manor and park complex.

As a result, premises for the management of historical parks were presented, aimed at using their potential in the development of rural communes.

2. Materials and Methods

This research covers many threads and consists of the analysis of indirect data (collected by the National Heritage Board of Poland [2017] and the Central Statistical Office [2020]) and direct data (own field research and market research of historic land property sales offer in rural areas).

2.1. Material and Method of Analysis Based on Indirect Data

The NID (National Heritage Board of Poland) report [35] contains general data on all objects entered in the register of monuments in Poland. From them, information about historical parks related to manors and palaces located in rural and urban-rural communes was selected. From the NID database [34,54] containing 6000 historical parks, independent parks and parks in city palace complexes were rejected. The subject of the research was 3433 parks in manor and palace complexes located in rural areas. This group included 1965 parks that are remnants of old manors and palaces. Moreover, there were 431 parks in palaces complexes and 1037 parks in manor houses (Table 1).

Table 1.

The number of parks in various types of historical prosperities covered by the study.

The analyzed parks were located in 16 voivodships: Greater Poland, Kuyavian-Pomeranian, Lesser Poland, Lodzkie, Lower Silesia, Lublin, Lubusz, Masovia, Opole, Podlaskie, Pomeranian, Silesian, Subcarpathia, Świętokrzyskie, Warmia-Masuria, West Pomeranian.

The NID database contains information about the object’s preservation in terms of the original size of space, the technical condition of architectural elements and the sanitary condition of plants. The NID studies also include a public opinion poll on monuments. It used information on the assessment of manor parks by the villagers. There was no detailed information on the behavior of an object’s composition, function, area or ownership form. Therefore, data collected by Rydel [12] were used to investigate the relationship between the preservation level of the compositional and historical values of the park and its everyday use. The author has compiled a numerical list of manor and park complexes in terms of their current use without division into provinces.

The research based on indirect data included:

- (1)

- comparison of the occurrence and concentration of historical parks in rural areas in particular provinces;

- (2)

- assessment of the state of preservation of historical parks in terms of (a) space conservation (b) historical composition, (c) technical and phytosanitary condition;

- (3)

- the relationship comparison between the way the object is used (its ownership status) and the degree of preservation of its historical and compositional function;

- (4)

- evaluation of the role and functions of historical rural parks based on surveys [53].

The data on the ownership, technical condition and functions of historical parks were compiled. Descriptive statistics were used in the data summaries. Data were presented in the form of numbers, percentages, proportion and detailed indicators. The quantitative statistical indicators and ratios were used to compare the concentration of historical parks in 16 voivodships. They were calculated based on such independent variables as the number of parks of various types, the number of municipalities, the number of inhabitants and the area of the province.

In order to objectify the results, the number of historic parks in voivodships was analyzed (Table 2) based on the following factors:

Table 2.

General data on manor and palace historical parks in Poland

- (a)

- The park distribution index as a ratio of the number of historical parks and park ensembles to the number of rural and rural-urban municipalities (parks No./municipalities No.);

- (b)

- Standardized social exposure index as the number of historical park ensembles per 10,000 inhabitants in given voivodeships, calculated according to the formula (parks No./10,000 inhabitants);

- (c)

- Standardized index of the spatial distribution of parks as several historical park ensembles per 100 km2 area (parks No./100 km2 area).

For the assessment of the degree of spatial concentration of parks in individual voivodeships, was used

- (d) Florence’s distribution index. Its value was calculated using the following formula:

- F—Florence distribution index,

- Y—percentage structure of the first variable according to spatial units (number of communes, voivodship area, number of inhabitants of a voivodship);

- P—percentage structure of the second variable by spatial units (number of individual kinds of park ensembles in voivodships).

Florence’s index ranges from 0 to 1. With F < 0.25, the parks under study are highly dispersed, i.e., they are not located in one space. When 0.25 ≤ F ≤ 0.49, the examined objects are characterized by average territorial concentration. At F > 0.49, the analyzed parks are characterized by high spatial concentration.

To assess the degree of preservation of the historical park in terms of their size, a 3-point interval scale was used, according to which: 1 point—an object not preserved within its area or has remained less than 50% of its area; 2 points—an object that has retained over 50–80% of its area or more, but the loss of part of the area has reduced the park’s compositional value; 3 points—an object that has been preserved at least 80% of its area or more and the loss of a part of the area has not reduced the park’s compositional value. The park preservation indicator was calculated according to the formula:

where: Ip—Indicator of park preservation,

- Npj—number of objects of a given behavior class

- Eg—number of objects of all classes

- D—degree of park preservation (1-poor; 2-moderate; 3-good).

An average preservation indicator close to 1 point indicates the dominance of objects in a poor state of preservation, an index relative to 2 suggests the supremacy of moderately preserved objects, an index close to 3 means that well-preserved objects dominate in the voivodship.

2.2. Material and Method Based on Direct Data

This article answers the question of whether the size and condition of the park significantly affect the price of the landed property. The study assesses the relationship between the cost of the manor/palace park complexes and the park/building condition (state of preservation) and park/building area. The research hypotheses were verified, that, in a manor house and park complex, the principal economic value is attributed to the building. The park is less critical, especially when it has a small area; its role in property valuation is overlooked.

The sales offers posted on 4 leading real estate websites in Poland [55,56,57,58] were reviewed. A review of 220 sale offers of mansions over a 3-year period (2018–2020) was made. 169 park-manor houses and palace complexes from 16 voivodeships were selected for detailed analysis. The chosen objects had complete data on buildings and vegetation such as building development area (including the manor house/palace and outbuildings), the park area, the condition of preservation, the shape of infrastructure (e.g., water system), spatial composition, plant species selection and the age of the trees. Price indices for facilities and parks per area unit (m2) were compared.

The offer price was analyzed in relation to a usable area of buildings and plot area (historical parks) in 16 voivodships. Data from individual voivodships were used in descriptive statistics; however, this variable was not taken into account to verify the hypotheses due to the small sample size in some voivodeships. Based on the descriptive and photographic record, the preservation of buildings and parks was estimated.

A 3-point scale was used to assess the condition of the building/parks, based on the NID report [53] and Rosłon-Szeryńska research [50], where: good condition—no need for repair/modernization; medium condition—repair/protective maintenance is necessary; bad situation—a high degree of degradation or ruin that requires significant renovation.

In the analysis of the size of the building/park, a 3-point scale was used, where

- (1)

- a small building has an area of up to 500 m2, medium—501–1000 m2, and large >1000 m2;

- (2)

- a small park is up to 5 ha; medium—5.1–10 ha, and large >10 ha.

To verify the hypotheses, Statistica 13.3 (TIBCO Software Inc.) was used to answer the research questions. For the overall statistical summary, a significant level of p < 0.05 was selected. The analysis used 2-way analysis of variance in the intergroup schema and multivariate regression analysis. Post-hoc analysis with the Tukey range test was used in the search for detailed differences between 2 means that is greater than the expected standard error:

where

- µi—µj is the difference between the pair of means to calculate this, µi should be larger than µj;

- µs is the Mean Square Within, and n is the number in the group or treatment.

For unequal sample sizes, the confidence coefficient is greater than 1—α for any 0 ≤ α ≤ 1. In other words, the Tukey method is conservative when there are unequal sample sizes.

A statistical description of the variables preceded the search for answers to research questions. The descriptive statistics examined such features of the research sample as:

N—observations’ number, Min—minimum, Max—maximum, M—average, Me—median, SD—standard deviation, SKE—skewness, K—kurtosis.

3. Results

3.1. The Distribution of the Historical Parks in Manor and Palace Complexes

Theoretical research covered 3433 historical parks in manor houses and palace complexes, most of which were located in Greater Poland (500), Pomerania (496), Warmia and Masuria (319), Kuyavian-Pomeranian (339) and Masovia (306). The smallest number of manor houses remained in Lesser Poland (173), Lubusz (68), Silesian (54) and Podlasie (38), where wooden manor houses dominated, and where the war damage was particularly severe (Table 2).

The largest number of manor parks is in Pomeranian (209) in Greater Poland (142), in Lublin (120) and Masovia (106). There are only five manor parks in Opole, and 9 in Podlasie and Lubusz. No palace and manor complex in the countryside has survived in Podlasie, and two such objects have been recorded in Lodzkie. There are as many as 54 palaces and park complexes in Kuyavian-Pomeranian. A similar number of these objects (51) occurs in Lower Silesia. The largest group are the manor parks, which today constitute an independent composition and spatial ensemble. Parks of this type have the largest share in West Pomeranian (392), Greater Poland (309), Warmia-Masuria (262) and Lodzkie (254). There are many post-manor/palace parks in Silesia (18), Podlaskie (29) and Lubusz (32).

The distribution of historical parks in rural and urban-rural communes was examined. West Pomeranian voivodeship has the most significant number, i.e., more than three post-manor/palace parks (3.47) per commune. There are over two parks (2.26) per commune in Warmia-Masuria. There is at least one park of this type in all municipalities in Lodzkie (1.44) and Greater Poland (1.37). In Silesia, only every ninth commune has a post-manor/palace park, and almost every fifth commune has a park-manor/palace complex. The Kuyavian-Pomeranian has the highest number of park and manor complexes in communes (1.83). In Podlaskie, Lodzkie and Opole this ratio is the lowest and amounts to 0.08; 0.12 and 0.18.

The distribution index of the analyzed parks (all three types) were developed as a ratio of the number of historical parks to the number of rural and rural-urban municipalities. The index value above one occurred in most voivodeships (Lesser Poland, Pomerania, Masovia, Subcarpathia, Lublin, Opole, Świętokrzyskie, Lower Silesia). The index of over two occurred in Greater Poland and Kuyavian-Pomeranian. The largest number of parks per one municipality are in the West Pomeranian voivodeship (4.86), i.e., almost five parks, and in Warmia-Masuria (3.19).

The standardized spatial distribution index was used to determine the number of parks existing in an area of 100 km2. The index value above 1 occurred in Lesser Poland (1.14), Świętokrzyskie (1.04), Warmia-Masuria (1.32), Lodzkie (1.51) and Greater Poland (1.68). The number of parks per 10,000 inhabitants in voivodeships was examined. The highest index was recorded by West-Pomeranian (2.91) and Warmia-Masuria (2.22). There is over one park per 10,000 inhabitants in Kuyavian-Pomeranian (1.63), Greater Poland (1.43), Lodzkie (1.11) and Lublin (1.02). The lowest index was recorded in Podlaskie (0.32) and Silesia (0.12).

The concentration of historical parks in individual provinces, communes and concerning the voivodeships area was examined using Florence’s Distribution Coefficient (Table 3 The Florence indicator, calculated on the basis of the differences between the percentage structure of the number of parks and the area of voivodeships, amounted to 0.3896 for manor parks, which means the average territorial concentration of manor parks in individual voivodships.

Table 3.

The assessment of the degree of spatial concentration of parks in individual voivodeships, according to the Florence’s distribution index.

Concerning manor parks, it amounted to 0.3029, which also means the average dispersion of this type of parks. For palace parks, Florence’s index is close to zero (0.0006), which means that the parks under study are highly dispersed, i.e., they are not located in one space.

The distribution of parks in the rural and rural-urban municipalities was also examined using the Florence distribution index. For post-manor parks, this factor was 0.3600; and for manor parks 0.2603, which represents an average concentration in relation to the population distribution. Concerning palace parks, this value is close to zero (0.0006) and means there is a large dispersion of these parks compared to the number of inhabitants in provinces.

The index reaches similar values when examining the difference between the percentage structure of the number of parks and the number of inhabitants of voivodeships. The Florence indicator amounted to 0.3181 for post-manor parks and 0.2993 for manor parks, which means the average dispersion of these objects concerning the number of inhabitants. For palace parks, Florence’s index is slightly higher (0.0663), but still close to 0-point, which means that the palace parks are highly dispersed concerning the population density.

3.2. The Preservation and Function of the Historical Parks in Manor and Palace Complexes

Based on the NID [2017] data, the state of preservation of the objects in terms of territoriality was assessed. Preserved parks are those that have been fully preserved within their boundaries. Moderately preserved parks are those where there has been a partial parceling out or change of the function. Poorly preserved parks are relics and remains of the park. The results of the assessment of the state of preservation of post-manor/palace parks are shown in the first part of Table 4. The largest number of parks has been preserved in West Pomeranian (365), Masovia (149), Warmia-Masuria (222) and in Lodzkie (208). Greater Poland has relatively fewer facilities in good condition (152) compared to the total number of parks (309). Silesian has the relatively most infrequent historical parks. There are also nine parks in good condition (which constitute 50% of all facilities of this type in this voivodeship). In Lubusz, only 44% of parks (14) have survived within their borders. Few post-manor parks (29) have survived in Podlasie; 72% of them have been preserved. Nationally, 1512 post-manor parks have retained their original area, which is almost 77% of such facilities. Nearly 5% of parks in this group (88) are fragmentary remains of the former park, which were parceled out. Taking into account the arithmetic mean of the analyzed group of parks, where there are 95 parks in good condition per voivodeship, 23 medium-preserved parks and nine poorly preserved parks, the following voivodeships fell below the average: Lubusz, Lower Silesia and Świętokrzyskie, where the number of parks in good condition is much lower than the mean, and the number of poorly preserved parks exceeds the arithmetic average.

Table 4.

Rate of the preservation of the original boundaries of the area of historical parks in Polish voivodeships.

The second part of Table 4 presents the results of the assessment of the preservation’s level of manor parks. Most parks of this type with a surviving manor house are located in Kuyavian-Pomeranian, of which 122 are well-preserved. Most manors have been preserved in Masovia (88), Lublin (95) and Lesser Poland (69) and Pomerania (46). Greater Poland has as many as 44 poorly maintained manors. There are 79 well-preserved manor parks in this voivodeship. Fifty-three manor parks have survived in Podkarpacie, which constitutes 55% of all facilities of this type in this voivodeship. Kuyavian-Pomeranian has 45 moderately and 42 poorly preserved manor parks, which accounts for almost 42% of all parks of this type in this voivodeship. The least well-preserved manor houses are in Opole (1), Lubusz (3) and Podlasie (5). In general, 690 manor parks in Poland are preserved in terms of area size, 187 parks are moderately preserved, and as many as 174 parks are poorly preserved. Manor parks, which have significantly reduced their area, constitute as much as 17% of this group. Taking into account the average of the analyzed type of parks, where on average there are 44 well-preserved manor parks per voivodeship, 12 medium-preserved parks and nine poorly preserved parks, Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship fell below the average.

Table 4 also includes the data on palace parks in Poland. Most palace complexes have been preserved in Kuyavian-Pomeranian (54), Lower Silesia (51) and Greater Poland (49), Lublin (48), West Pomeranian (47) and Mazovia (42). Palace and park complexes in Lower Silesia (42), Greater Poland (41) and Lublin (39) are well preserved. Lesser Poland (86%) and Lublin (81%) have a relatively higher percentage of preserved objects. Podlasie does not have any surviving palace complexes in the countryside, and there are two such buildings in Lodzkie, and they are poorly preserved. Relatively few surviving palaces and park ensembles remained in Świętokrzyskie (2).

Taking into account all palace parks in rural areas in Poland, 72% of them are well preserved within their borders, and 13% of them have lost a large part of their size. On average, 20 well-preserved, four moderately preserved and three poorly preserved palace parks are in one voivodeship. Compared to the national average, Lodzkie is the worst, with only two parks of this type—both poorly preserved. Moreover, in Świętokrzyskie, Lubusz and Subcarpathia, the number of well-preserved palace parks is lower than the average, and the number of poorly preserved parks is higher than the average. Taking into account all palace parks in rural areas in Poland, 72% of them are well preserved within their borders, and 13% of them have lost a large part of their area. On average, 20 well-preserved, 4 moderately preserved and 3 poorly preserved palace parks are in one voivodeship. Compared to the national average, Lodzkie is the worst, with only two parks of this type—both poorly preserved. Moreover, in Świętokrzyskie, Lubusz and Subcarpathia, the number of well-preserved palace parks is lower than the average, and the number of poorly preserved parks is higher than the average.

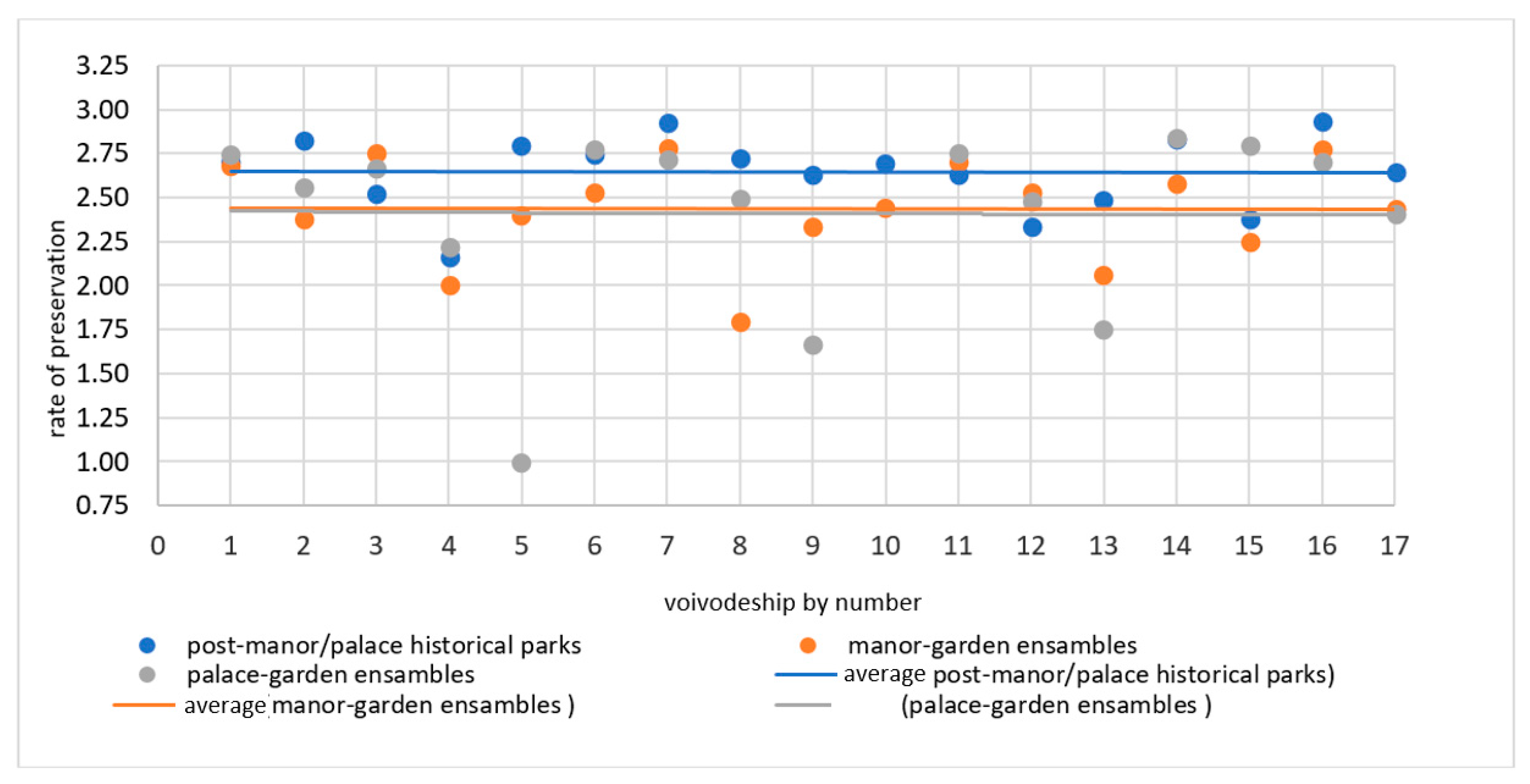

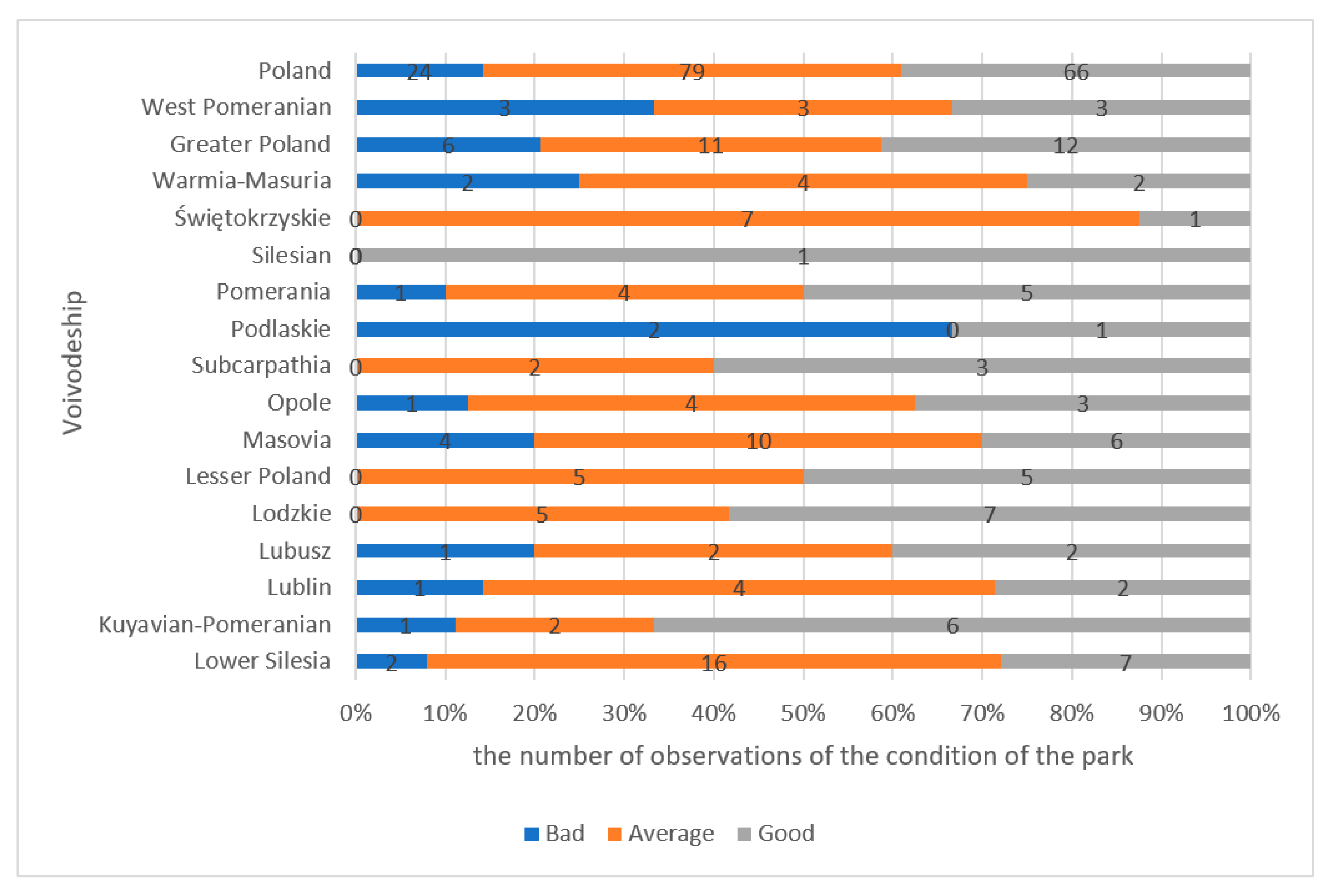

Measurements were standardized by developing an indicator of the preservation of post-manor/palace historical parks (Figure 1 and Table 4). The average preservation index of post-manor historical parks is 2.64 and means the domination of medium and well-preserved parks. In comparison, the preservation index of manor parks is lower; it amounts to 2.44. The lowest value (although in terms of the average rating) is the index of palace parks behavior and it amounts to 2.41. Referring to Figure 1 the numbers on X-axis represent voivodship as follows: 1-Greater Poland, 2-Kuyavian-Pomeranian, 3-Lesser Poland, 4-Lodzkie, 5-Lower Silesia, 6-Lublin, 7-Lubusz, 8-Masovia, 9- Opole, 10-Podlaskie, 11-Pomerania, 12-Silesian, 13-Subcarpathia, 14-Świętokrzyskie, 15-Warmia-Masuria, 16-West Pomeranian.

Figure 1.

The average preservation indicator of post-manor parks and manor/palace park complexes in individual provinces in Poland (own study based on the NID database).

The highest values of the preservation index are the post-manor parks in West Pomeranian (2.93), Masovia (2.92), Warmia-Masuria (2.84), Kujavian-Pomeranian (2.83) and Łodzkie (2.80). The lowest index values in this group are Lubusz (2.16) and Silesian (2.33). The highest amount of the preservation index has manor parks in the following voivodeships: Masovia (2.78), West Pomeranian (2.77), Lublin (2.75) and Pomerania (2.70). Opole and Lubusz have the lowest index value in this type of park—1.80 and 2.00, respectively. Palace parks achieved the highest preservation index values in Warmia-Masuria Voidship (2.84), Greater Poland (2.80) and Lesser Poland (2.77). The lowest index is in Lodzkie (1.0). A palace parks preservation index below two was recorded in Subcarpathia (1.67) and Świętokrzyskie (1.75).

The summary indicator of the preservation of historic parks in all types of facilities is the highest in Masovia (8.42), West Pomeranian (8.40) and Warmia-Masuria (8.26). The lowest total indicators are Podlaskie (5.13), Lodzkie (6.20), Świętkorzyskie (6.31) and Lubusz (6.38). Greater Poland index is at the average level and amounts to 7.42.

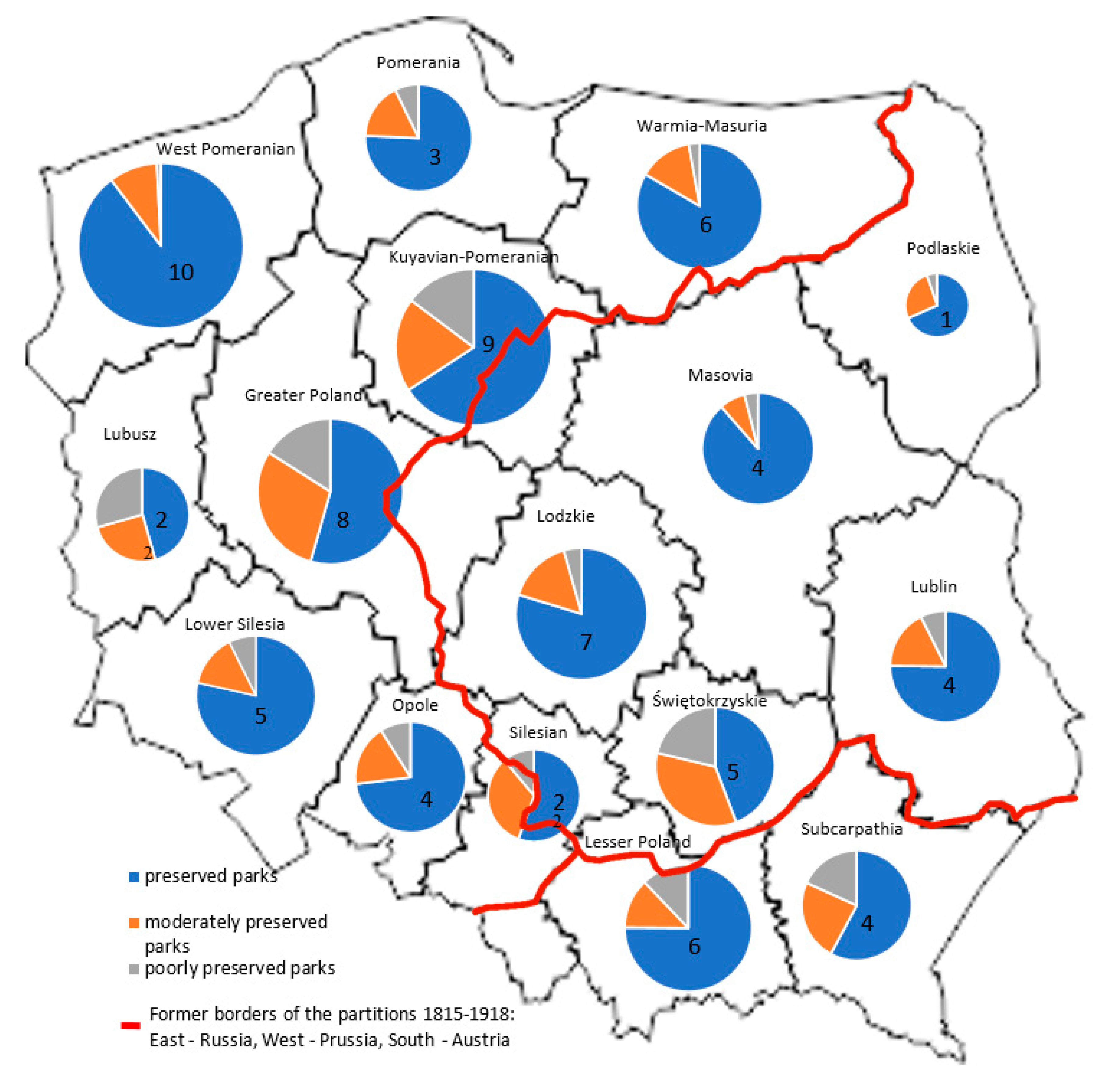

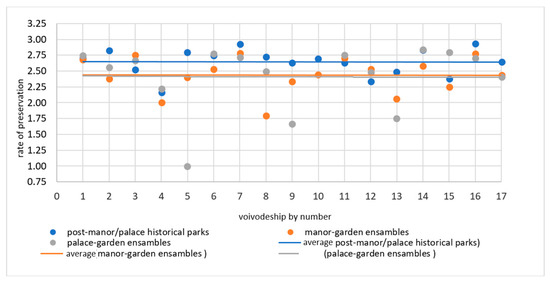

The fourth part of Table 4 and Figure 2 provides an overall assessment of the state of conservation of all types of historic parks in rural areas. The table contains information on the percentage share of sites with different degrees of preservation. Nationwide, 69% of all types of historical parks in rural and rural-urban communes have been preserved within the original area boundaries. In total, 11% of all surveyed parks are poorly preserved. Referring to Figure 2 the standardized index of spatial distribution of parks (No. parks/100 km2) values as follows: (1) >0.20; (2) 0.20–0.50; (3) 0.51–0.71; (4) 0.72–0.92; (5) 0.93–1.13; (6) 1.14–1.34; (7) 1.35–1.55; (8) 1.56–1.76; (9) 1.77–1.97; (10) <1.97.

Figure 2.

The number and degree of preservation of historical parks occurring independently and in palace-garden ensembles in individual voivodeships presented as a percentage (own study).

Figure 2 shows the number and degree of preservation of all historical parks occurring independently and in palace-garden ensembles in individual voivodeships, presented as a percentage. These data are depicted in spatial terms on the map of Poland, with division into voivodships. The circular diagrams on the map are of different sizes, which reflects the other distribution of historical parks in voivodships. In this case, the standardized index of the spatial distribution of parks presented in Table 2 was used. The lowest index 0.19 in Podlasie means that one park covers over 500 km2 of the area in this voivodship. The highest index is 2.17. The sizes of the circular diagrams are included in 10 intervals from the lowest to the highest index.

The map shows the border of the partitions of Poland in the years 1815–1918. It can be noticed that most of the historic parks in the former landowners’ seats have been preserved in the north-west, central-eastern and southern part of the country. The fewest facilities of this type are located in the east and north-eastern part of Poland. It can be stated that many parks were established in the area under Prussian rule. The lands under Russian control were lower in manor houses.

Well-preserved parks have the highest share (90%) in West Pomeranian. Moreover, Masovia has favorable results in this respect, where well-preserved parks constitute 89% of all parks in this voivodship. A high share of preserved parks (83% and 80%) is also found in Warmia-Masuria and Lodzkie. The latter voivodship has many manor parks with preserved area boundaries, which influenced the overall assessment, and differed from the detailed evaluation of the condition of manor and palace parks. The lowest percentage of well-preserved parks is in Świętokrzyskie (44%), Wielkopolska (54%), Silesian (56%) and Subcarpathia (58%). The largest share of poorly preserved parks is in Lubusz (29%), Świętokrzyskie (21%) and Subcarpathia (18%).

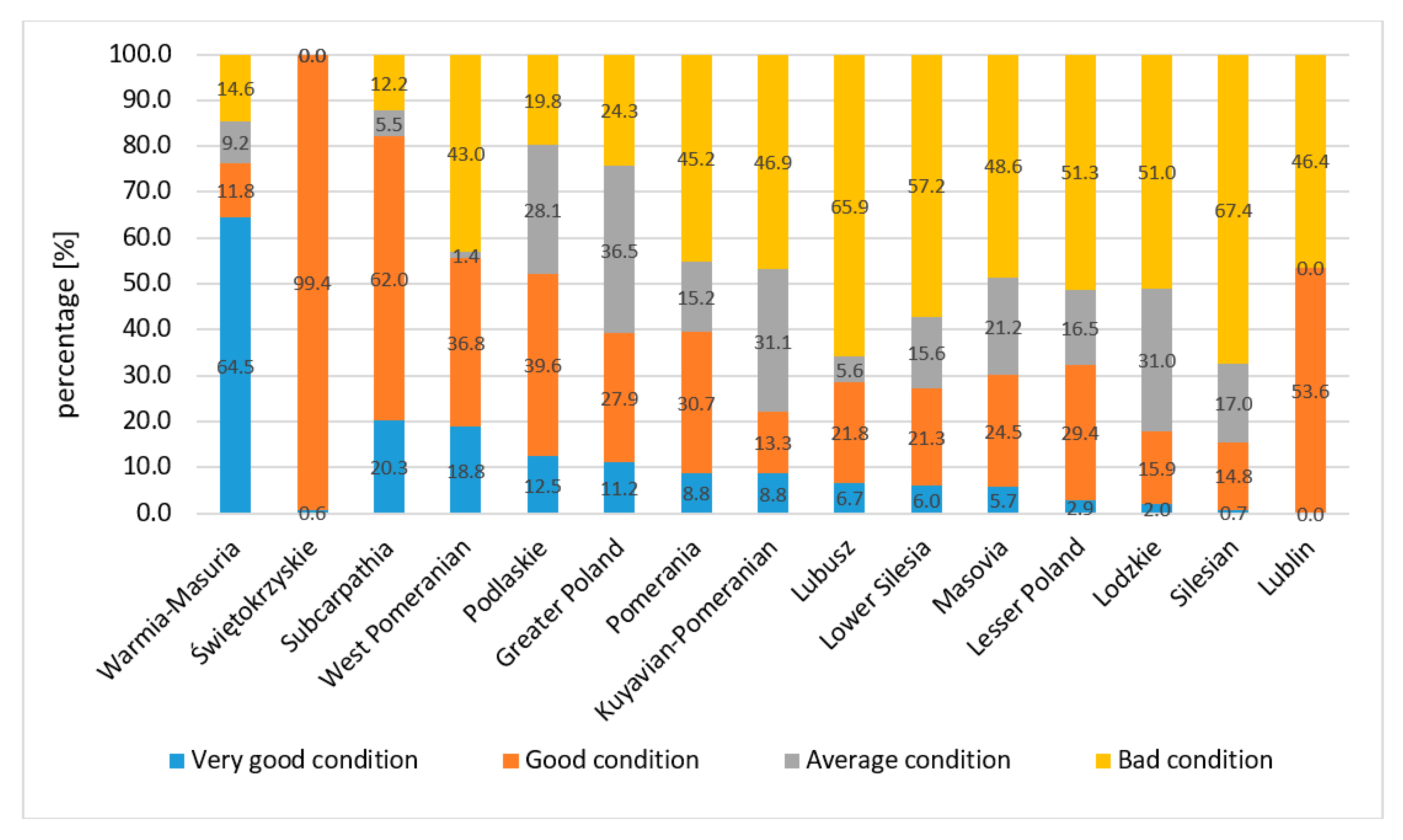

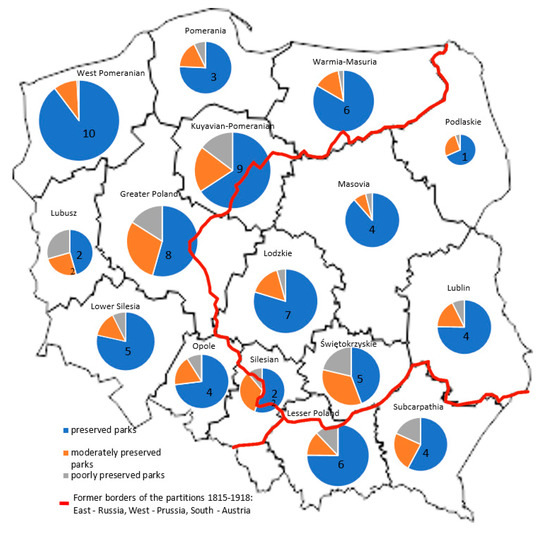

The technical and phytosanitary conditions were assessed. In Figure 3 below, based on NID data (2017), the objects with different degrees of preservation divided by regions are presented. On average, most parks are in bad (40.4%) and relatively good (30.1%) condition. The medium condition of preservation is in 16.1% of parks and very good is 13.3%.

Figure 3.

Preservation of parks in technical and phytosanitary terms according to NID data (2017).

The assessment of the technical condition of parks is worse than the evaluation of behavior within the borders. The parks in Warmia-Masuria are in the best technical and sanitary condition (64.5%). An excellent rating also applies to 20.3% of parks in Subcarpathia, 18.8 in West-Pomeranian, 12.5% in Podlaskie and 11.5% in Greater Poland. Parks are well-rated in technical terms in Świętokrzyskie (99.4%), Subcarpathia (62%), Lublin (53.6%), West Pomeranian (39.8%) and Podlaskie (39.6%).

Parks in Silesia are in the worst condition—as many as 67.4% of them received a bad rating. More than 50% of parks are in the poor technical condition in Lubusz (65.9%) Lodzkie (51%) and Lesser Poland (51.3%). Moreover, there are many poorly preserved parks in Masovia (48.6%), Kuyavian-Pomeranian (46.9%), Pomerania (45.2%) and in Lublin (46.4%).

In the next step, the preservation of the historical and compositional tissue of the parks studied was assessed. The assessment of the preservation of historical and compositional values of parks was related to the form of their ownership and their function. Data are included in Table 5. For comparison, similar data are presented for manor parks from 1969 and 2014, i.e., from the time after the enfranchisement of manor houses.

Table 5.

Preservation of historical values (composition and species structure of the park), status for 2014 and forms of ownership of manor parks in 1969. Own study based on data from Rydel [12] and the Board of Museums and Monument Protection (ZMiOZ) [9].

The collected data show that out of the reported 3015 manor and palace complexes, as many as 1965 were not usable and fell into ruin. None of these objects have retained their historical and compositional values. In total, 98 manors/palaces are the remnants to which the descendants of the owners returned. In this group, about 30% of the objects are a continuation of the landed gentry heritage. The life of these manors today is characterized by a concern for tradition, a great attachment to the family seat and a specific atmosphere of authenticity.

The analyze of the forms of ownership of landowners’ manors throughout history, leads to the conclusion that only museum activities provide sufficient protection for these objects. Most of the state-owned manors used for noncultural purposes have been degraded and lost their historic value.

According to Rydel [12], there are about 40 estates that were repurchased by the heirs from the Agricultural Property Agency (pol. ANR) and sold because they could not afford to renovate and maintain the manor or palace. In other cases, the descendants regain, after several years of proceedings with the state or local authorities, the useless ruins.

There are as many as 380 manors in the local authorities’ hands. They serve as schools, kindergartens, orphanages, health care centers and social welfare homes, cultural centers and communal houses. In this group, only seven objects (1.8%) retain their traditional appearance, composition and historical form. When the school was moved into the manor or palace after 1945, the standard was to cut out part of the park for the children’s playground. In the worst condition in this group are manors dedicated to social and municipal apartments.

In total, only 6 of the 58 manor parks and palaces, which were dedicated to the farmhouses, have preserved their original layout, historical and compositional values. The condition of these objects is different. Some manors taken over by private persons managing the land are in good condition, renovated and used as apartments and offices. Some are devastated, used as an office building without taking care of the architectural monument or abandoned.

More and more guesthouses, hotels and conference and training centers are being organized in historic manor and palace complexes. A total of 265 of them were registered, with only 18 of them (6.8%) recreating the traditional look of the building and its surroundings. However, in most manors and palaces scattered all over Poland, which has a hotel and service functions, it is not easy to find any symbols of the past, besides the external façade.

The situation is similar in the case of private owners, who often do not have such high funds at their disposal to take care of preserving the historical values of the manor house. Only 10% of the 150 privately owned buildings have a maintained traditional look. Only in a few cases, we can talk about functions similar to the prewar role of the landed gentry estate center. Most of the private homeowners in these historic buildings are artists, managers and CEOs of large companies. The seat of the Penderecki family in Lusławice is a real gem among this category of manors. Krzysztof Penderecki not only saved the remaining park, but extended it, and today, with more than 20 hectares, the park is a magnificent arboretum containing many native and foreign tree species (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Examples of well-preserved manor parks in terms of history and composition: (a) manor house of the Penderecki family in Lusławice; (b) Palace-park complex of the family Ostrowski in Korczew. Today it is a private museum (photo by E. Rosłon-Szeryńska).

The best-preserved, according to the historical value, is the situation of the manors acting as museums (68) and transferred to open-air museums (11). There are, outside the cities, 60 state and local regional and biographical museums and eight private ones located in manors and palaces. The latter appeared after 2000. The museum created with excellent knowledge attracts tourists and is one of the few places where one can feel the traditions of Polish landed gentry. Noteworthy is the palace and manor house in Korczew belonging to the Ostrowski family. In 1989, the daughters—Krystyna, Beata and Renata—returned to Poland. They bought the building for a nominal fee and started its renovation, which continues to this day. The owners lived in one wing of the building; the rest was allocated to the museum. Both the palace and the park will be restored to their former glory (Figure 4b).

It can be concluded that only 156 manors and palaces existing in Poland (outside the cities) have preserved architectural and historical values, referring to the original condition. That is, less than 1% of the situation from 1939 and 5.2% of registered park and manor or palace complexes.

3.3. The Value of the Historical Parks in Manor/Palace Complexes

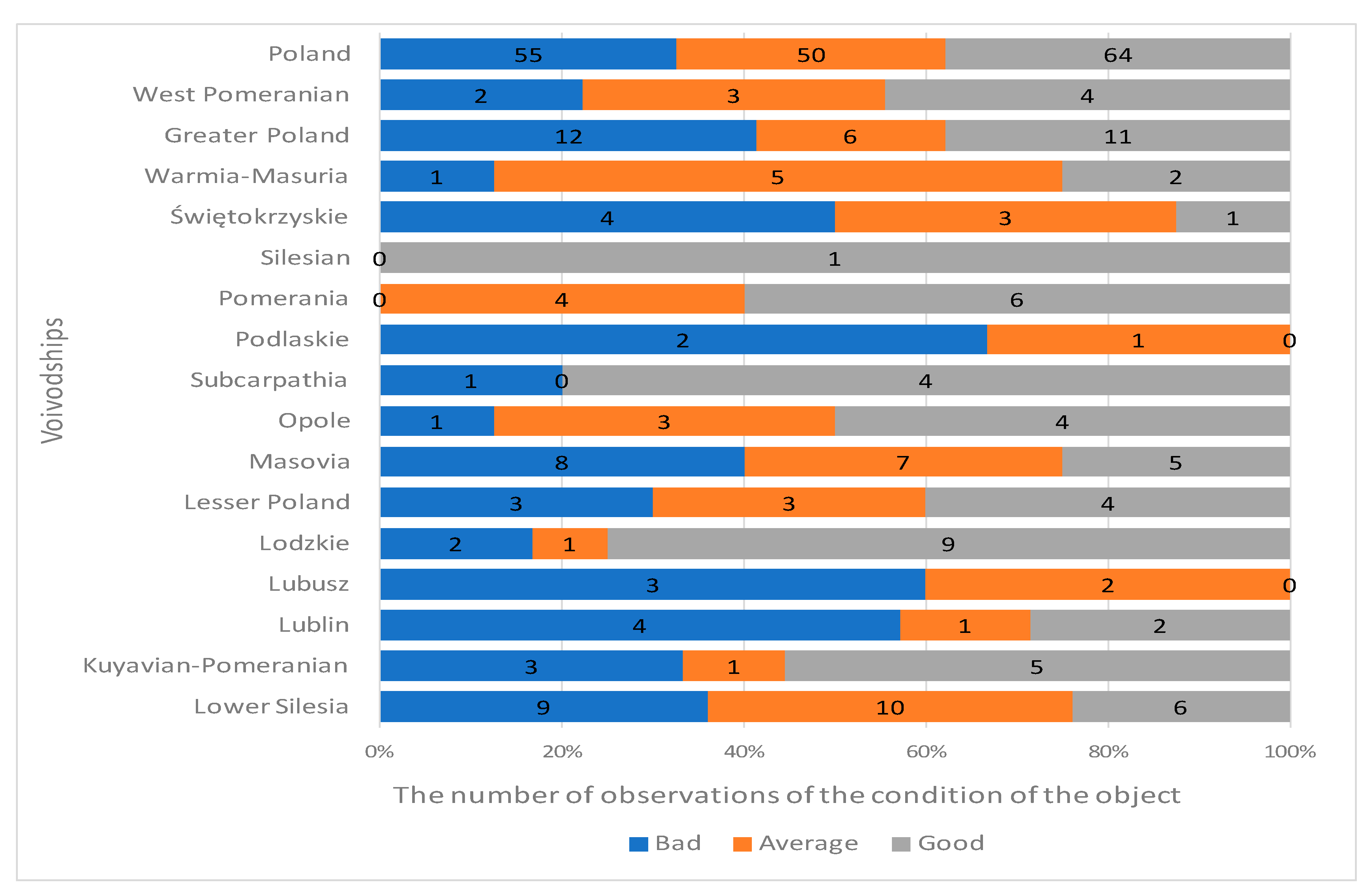

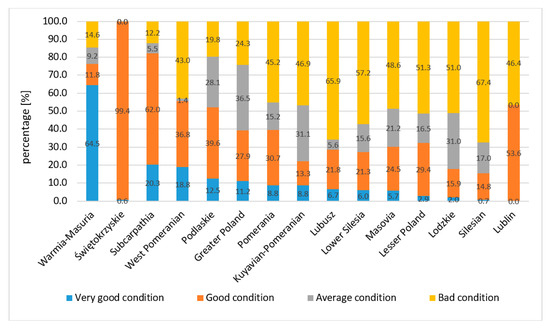

Data was collected on 191 offers for the sale of historic facilities with the park. It was to verify the adopted hypotheses about the underestimated value of the park in the market prices of these facilities. The study assesses the relationship between the cost of the park/building and their condition (preservation’s status), and area. In total, 169 manor-palace-park complexes offered for sale were subjected to statistical analysis. The list includes the offers of the manor buildings themselves with a residual or without park (8) and parks without manor (palace) buildings (14), which were not included in the statistical analysis. The study sample included the largest number of objects from Greater Poland (29), Masovia (20), Lower Silesia (25), Lodzkie (12) and Lesser Poland and Pomerania (10 each).

The ownership of 85 objects put up for sale was established. The level of conservation of parks in these facilities was compared depending on the form of ownership. It turns out that parks owned by municipalities are in the worst condition. Out of 15 such facilities, as many as 10 were in poor condition, and five were in average condition. Additionally, in a poor and average condition, there are five manor complexes sold, which are in the hands of educational institutions, upbringing institutions and community centers, subject to the county or municipality. The status of preservation of manors owned by private persons seems better (54 sales offers). Almost 41% of park facilities are in poor condition, and 24% are in good condition. Parks intended for hotel services are the best maintained. There were as many as 12 offers for the sale of such facilities. The status of conservation of the parks is mainly very good and good (10 objects). There is one park in poor condition and one in fair condition. Compared to the research conducted by the authors in this regard in 2018 [50], it should be emphasized that the number of hotels sold has increased, which may indicate financial problems and difficulties for the owners.

Table 6 and Figure 5 provide information on buildings whose average price per square meter of built-up area was PLN 3215.39. The average cost for the entire manor house or park and palace complex was PLN 2848.004. The mean building area was 1133 m2. The highest average unit price per square meter of a manor/palace building was recorded in Kuyawian-Pomeranian (PLN 6078.75), Masovia (PLN 5185.78) and Lublin (PLN 5107.37). The lowest unit price per square meter of a facility was in Lubusz (PLN 1089.53), Podlaskie (PLN 1372.22) and West Pomeranian (PLN 1887.81). High kurtosis in Greater Poland, Lublin, Lower Silesia and Lubusz means that the price index is more concentrated at the mean value than at the normal distribution.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics of the object price index broken down by voivodeship.

Figure 5.

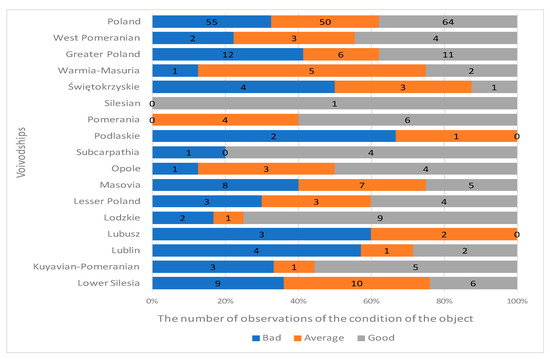

Numerical share of the object’s condition, broken down by voivodships (N = 169) (own study).

On the other hand, the negative value of kurtosis in Kujavian-Pomeranian, Lodzkie, Lesser Poland, as well as in Subcarpathia and Pomerania indicates a more significant dispersion of the value of offers compared to the normal distribution and the presence of a more significant number of offers with extreme values of offer prices. In Mazovia, the amount of kurtosis is close to 0. It indicates a flattening of the distribution and many offers with similar unit prices. In Świętokrzyskie, the distribution of prices is left-skewed, so most of the offer prices are higher than the average. On average, park and manor complexes in Lublin were more expensive than the national average, where a small price differentiation was noticeable, and also in Kujavian-Pomeranian and Lodzkie, where there was a large price spread.

Table 7 and Figure 6 provide information on parks whose average price per square meter of built-up area was PLN 56. The mean park area was 3.5 ha. Higher average park prices are visible in Lublin, Podlaskie and Silesia.

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics of the park price index broken down by voivodeship.

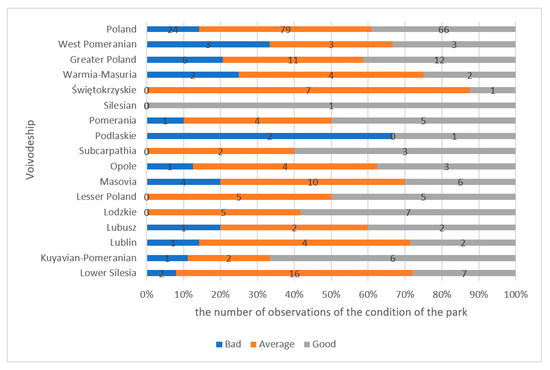

Figure 6.

The park’s condition as a number, broken down by voivodships (N = 169) (own study).

The highest average unit price per square meter of a manor/palace park was in Lower Silesia (PLN 156.86) and Subcarpathia (PLN 114.29). The lowest unit price per square meter of the park was recorded in Podlaskie (PLN 22.98), Warmia-Masuria (PLN 26.24) and Lubusz (PLN 26.35). In contrast, the highest value was recorded in Lublin (PLN 223.43), Lower Silesia (PLN 197.90) and Masovia (PLN 151.10).

The high value of kurtosis in Greater Poland, Świetkrzyskie, Warmia_Masuria, Pomerania and Lower Silesia means that the price index is more concentrated at the mean value than at the normal distribution. In turn, the negative value of kurtosis in Kujavian-Pomeranian shows a more excellent dispersion of the value of offers compared to the normal distribution and more offers with extreme values of offer prices. In Opole, the amount of kurtosis is close to 0. It indicates a flattening of the distribution and many offers with similar unit prices. In Subcarpathia, the price distribution is left-skewed, so most bid prices are above average.

Hypothesis Verification

H1 was verified. In a similar analysis, the object price index (PLN/m2) was assessed by a two-factor analysis of variance. The model uses the size of the object (small, medium and large objects) and the condition of the object (bad, average and good condition). Table 8 summarizes this analysis.

Table 8.

Summary of the two-way analysis of variance for the object price index (PLN).

The analysis showed no interaction effect between the object condition and the size of the object, F(4, 160) = 2.273; p = 0.064; η2 = 0.05. However, there was a major effect on the size of the object, F(2, 160) = 5.795; p = 0.004; η2 = 0.07 and the main effect of the state of the object, F(2, 160) = 25.362; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.24. The indicated main effects suggest that there are differences in the performance of the object price index between the levels of the variables.

The analysis showed no interaction effect between the object’s condition and its size, F(4, 160) = 2.273; p = 0.064; η2 = 0.05. However, there was a main effect on the size of the object, F(2, 160) = 5.795; p = 0.004; η2 = 0.07 and the main effect on the state of the object, F(2, 160) = 25.362; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.24. The main effects indicated suggest that there are different results of the object price index between the levels of variables.

In search of specific differences, post hoc analysis by Tukey’s test was used. The differences between objects of different sizes in the object price index level present Table 9.

Table 9.

Summary of post hoc analysis by Tukey’s test of the price index [PLN/m2] of an object, broken down by object size.

Post hoc analysis showed that small objects (M = 5056.94; SD = 4133.91) are characterized by a higher object price index compared to medium objects (M = 2804.16; SD = 3094.05) and large (M = 2589.38; SD = 2378.29). There is no significant difference in the price index level between medium and large properties.

In the second post hoc analysis, the Tukey test assessed the clear differences in the level of the price index of the object broken down by its condition. The research is presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Summary of the object’s price index [PLN/m2] post hoc analysis using Tukey’s test, broken down by the condition of the object.

Post hoc analysis showed that objects in good condition (M = 5024.79; SD = 3685.39) are characterized by a higher price index compared to objects with average (M = 2212.75; SD = 1887.1) and poor condition (M = 1539.87; SD = 3111.42). There is no significant difference in the price index level between objects with poor and average condition.

H2 was verified. The two-factor analysis of variance was used to assess the differences in the level of the pair price index between parks of various sizes and condition of the park. Small, medium and large parks were additionally assessed according to the park condition (bad, average, good). The summary of this analysis is presented in Table 11.

Table 11.

Summary of the two-factor analysis of variance of the park price index (PLN/m2).

The analysis showed that there is a main effect on the variable size of the park, F(2, 160) = 9.574; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.11. In the results, the main effect on the park’s condition turned out to be insignificant, F(2, 160) = 0.271; p = 0.763; η2 = 0.01. The effect of interaction on park size factors also turned out to be insignificant, F(4, 160) = 0.126; p = 0.973; η2 = 0.01.

The main effect of the size of the park suggests a difference in the park index. The assessment of detailed differences was carried out in a post hoc analysis using the Tukey test as presented in Table 12.

Table 12.

Summary of the park’s price index (PLN/m2) post hoc analysis using Tukey’s test, broken down by park size.

Post hoc analysis showed that small parks (M = 166.82; SD = 223.19) are characterized by a higher park price index compared to medium parks (M = 46.97; SD = 42.99) and large parks (M = 28.68; SD = 28.19). There is no significant difference in the level of the price index between medium and large parks.

H3 verified. The last element of the analysis is the price assessment depending on the park and object. The price predictors were: the area of the facility (m2), the area of the park (ha), the condition of the facility and the condition of the park. Multivariate regression analysis was used for the study, as shown in Table 13.

Table 13.

Summary of multivariate regression analysis for absolute price.

The presented model fits the data well, F(4, 164) = 18.207; p < 0.001. The model is better at predicting price volatility than the arithmetic mean. The selected predictors allow for the prediction of 29% price volatility. Significant predictors turned out to be the area of the object, the condition of the object and the area of the park.

In the model, the condition of the park turned out to be irrelevant in predicting the price. The strongest predictor is the area of the object (β = 0.28; p < 0.001). The condition of the object (β = 0.22; p = 0.008) and the park area (β = 0.2; p = 0.005) turned out to be weaker but still important in predicting price volatility. The relationships of the predictors with the dependent variable are positive and weak. The increment in the area of the facility, improvement of the condition and area of the park will increase the price.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Occurrence of Historical Parks in Poland

The results of the research present a detailed assessment of not only the number of manor and palace park complexes but also their distribution and potential accessibility thanks to the applied indicators taking into account a different number of communes in the voivodeship, different number of inhabitants and the area of voivodships. Many authors have studied the number and saturation of manor houses and palaces in individual provinces, omitting parks as an essential element of the complex [1,2,12,42]. Meanwhile, there are today devoid of an architectural dominant in the form of a manor or palace, 1965 residential parks, which constitutes as much as 57% of all surveyed landowners’ residences. In this study, three groups of objects were distinguished: (1) post-manor/palace parks as a remnant of the former complex, (2) manor parks and (3) palace parks, which contributed to the greater detail of the obtained data. Authors rarely separate manor houses located in cities from manor houses located in rural areas [42]. Few works use indicators instead of numerical data (e.g., the number of manors per 1000 km2), which is more objective in nature [42]. This work is innovative in this respect. That is why obtained results regarding both the number and distribution of these cultural monuments, partially differ from the results of other authors.

Many authors [10,12,19] give Greater Poland as the voivodeship with the nominally largest number of monuments. Apart from Greater Poland, according to Kozak [42], Lower Silesia and Masovia are also the richest in palaces and manors. Taking into account the saturation of manors on 1000 km2, he considered the region of Lower Silesia, Greater Poland, Masovia and Kuyavian-Pomeranian to be the richest in these types of buildings. The author included in his assessment all manors, palaces and castles, including those located in cities [42]. In this study, the relative indicators of the spatial, social and administrative distribution of monuments used in this study placed the Greater Poland Province on a high, but not the first position.

Taking into account the park distribution index, the largest number of residential parks per commune is in West Pomeranian (as many as 4.86), in Warmia-Masuria (3.19) and Kuyavian-Pomeranian (2.67). The smallest number of such objects is in Podlaskie (0.36), Silesian (0.46) and Lubusz (0.93).

Taking into account the spatial distribution of residential parks, for every 100 km2 in West Pomeranian voivodship, there are the most, i.e., 2.17, of such objects. In Kuyavian-Pomeranian there are 1.89 parks per one area unit. The lowest spatial index of parks’ distribution is found in Podlaskie (0.19), Silesian (0.44) and Lubusz (0.49).

On the other hand, when examining the availability of residential parks, there are almost three manors per 10,000 inhabitants in West Pomeranian and over two in Warmia-Masuria. The lowest indicator in this respect is in Silesian (0.12), and Podlaskie (0.32).

All the authors unanimously define Podlaskie [10,42] as the poorest in manors and palaces, which was confirmed by this study. Kozak also mentions Świętokrzyskie in this group. This study has not confirmed it, which is probably a result of the omission of manors located in cities. Detailed research of the authors of this article also showed that Silesian and Lubusz are poor in estates in rural areas.

When assessing the demand for manors in rural areas, it is worth taking into account the presence of the natural conditions of a given unit. Lubusz and Podlaskie voivodships (as well as Subcarpathia, Pomerania and West Pomeranian) are characterized by a high degree of forest cover (>35%). Therefore, the shortage of landscaped green areas will not be as noticeable as in the case of some communes of the Lodzkie; often the only tree stands in a given locality.

When assessing the reasons for the uneven distribution of landowners’ courts, one can agree with the majority of authors. In general, a large concentration of manors occurs in the territory of the former Prussian partition and in the central area, which was once the core of the Kingdom of Poland and economic and economic assets. A large number of manor houses in the north of the country is related to the Prussian policy in this area, but also to the wave of economic recovery in the 19th Century, which took place in Pomerania and Western Poland [42].

4.2. The State of Preservation of Historical Parks in Poland

Taking into consideration the condition of estates, their historical (original composition), technical and sanitary values (quality of small architecture elements and greenery health) and spatial form preservation (range of boundaries) are assessed [29]. In this article, the authors evaluated historical parks in terms of these three aspects.

The status of preservation of the manors can be inferred from the NID reports, which are updated at distant time intervals. The data collected by the NID [34,55], although extensive, are not complete, which makes it difficult to conduct comprehensive analysis. Historical parks are included in the study too generally, together with city parks created as an independent garden complex. As a result, it is required to complete the data independently with information such as the size of the park, type of establishment, features of the composition and development standard, and above all, the ownership status. Data on the state of conservation of the parks are incomplete as they do not have information on the situation of the parks in Opole [34]. Many studies are too general or too superficial to present the threads, based on which it is difficult to draw unambiguous conclusions. The authors of this study used many sources to carry out a detailed assessment of the residential parks under investigation on a national scale. The results again vary depending on the context of the evaluation.

Post-manor/palace parks in West Pomeranian (2.93) and Masovia (2.92) are in the best condition considering the preservation of the site boundaries; manor parks in Masovia (2.78); and palace parks in Warmia-Masuria (2.84) and Greater Poland (2.80). The worst performers in this respect were historical parks in Podlaskie (2.69) and Łodzkie (2.80); manor parks in Opole (1.80) and Lubusz (2.0), and palace parks in Podlaskie (no objects) and Lodzkie (1.0). Taking into account the total index of parks’ preservation, the best preserved were historical sites in Masovia (8.42), West Pomerania (8.40) and Warmia-Masuria (8.26), and the worst in Lodzkie ( 6.20) and Podlaskie (5.13).

The assessment of the examined objects in terms of their technical and phytosanitary condition looks slightly different. Here, the best-preserved historical parks in good and very good condition are located in the Warmia-Masuria (64.5%), Subcarpathia (62.3%) and Świętokrzyskie (99.4%) voivodships. The largest number of facilities in poor condition is in the following voivodeships: Silesia (67.4%), Lubuskie (65.9%) and Lesser Poland and Lodzkie (51% each).

Again, there are differences between the results of other authors and our studies, due to differences in the level of detail of the assessment. For example, the authors mainly emphasized the presence of the largest number of relatively well-preserved historical parks and manors in Great Poland and Masovia. The situation in the east of Poland and the Lodzkie Province is described as the worst [1,10,12]. The authors [10,42] drew attention to the poor condition of manors in Eastern Poland (including Podlaskie), which results from historical, political, social and economic conditions, but also because of wooden buildings in this part of the country. War damage, in particular leading to the destruction of cultural property, was most noticeable in Masovia, Pomerania and Podlaskie [10,42].

4.3. Contemporary Use and the Potential Value and Use of Historical Parks in the Development of Communes

Among many reasons of the poor preservation status of manors, the authors [23,28,29] agree that: change of ownership, change of function, and thus many years of neglect and inadequate management of these objects. Obtained results confirmed that the worst preserved original style and composition are parks subject to local authorities’ units and the state treasury, intended as council houses, health centers, schools, and often standing empty, deprived of proper care.

Also, according to Gancarz-Żebracka [52], most mansions belong to local authorities. Renovation is too expensive; hence the condition of these facilities is assessed as low. Problems related to difficulties in the revalorization of facilities, high renovation costs and legal problems lead to their progressive degradation.