Farmers’ Livelihood Adaptability in Rural Tourism Destinations: An Evaluation Study of Rural Revitalization in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

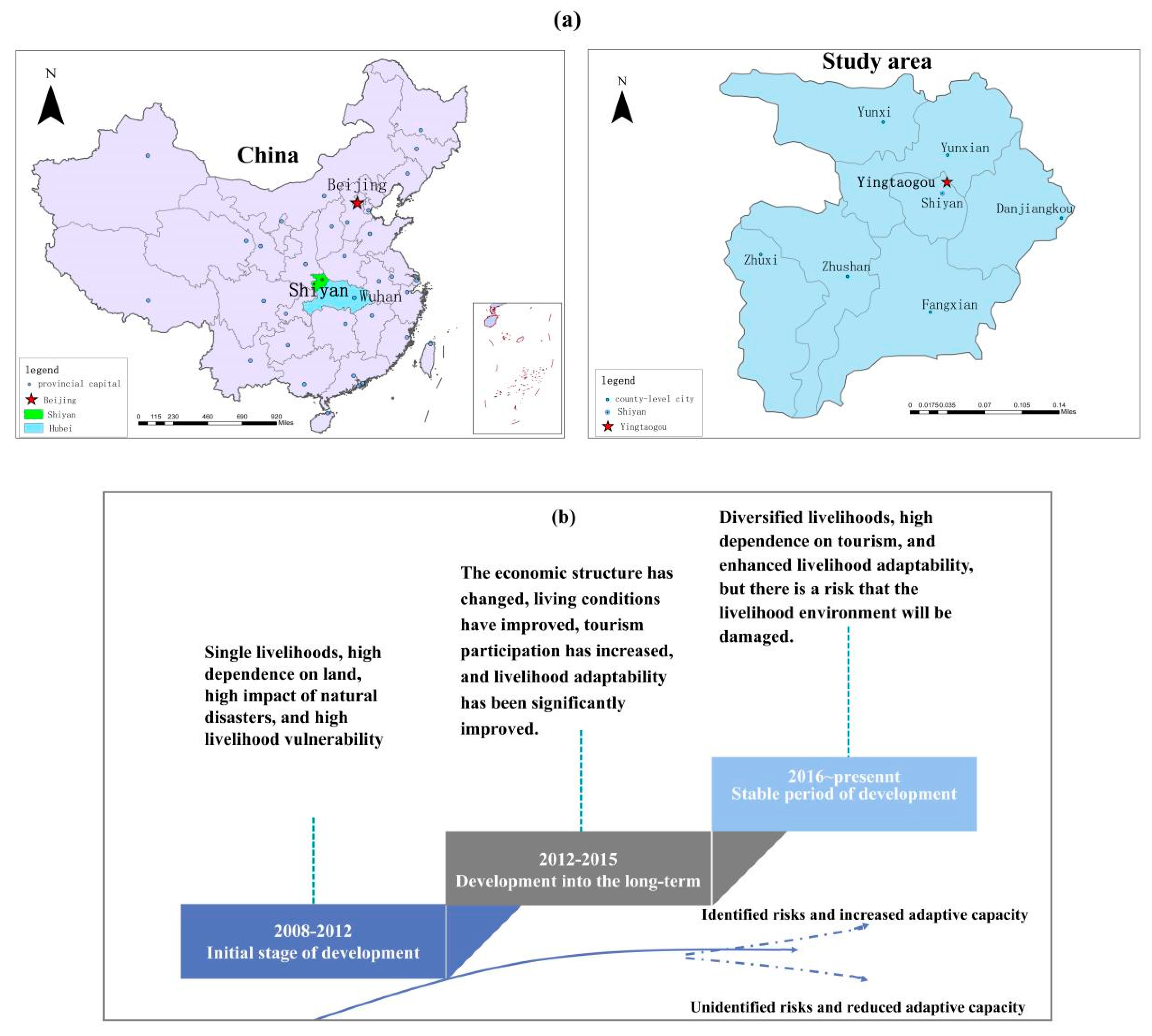

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Data Sources

2.2.2. Research Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Evaluation Index System

3.2. Categorization of the Adaptive Behavior of Farmers

3.3. Analysis of Farmers’ Adaptive Capacity

3.4. Identification of the Obstacle Factors which Affect Farmers’ Livelihood Adaptive Capacity

- (1)

- Tourism livelihood type: Household savings, household durable goods value, and family training opportunities are the main obstacles to the improvement of the livelihood adaptability of this type of farmer. The value of household savings and household durable goods directly affects the number and quality of tourists received by such farmers. At the same time, the opportunity for families to receive training affects the quality of the entire family’s labor force. When families have more training opportunities, farmers will take advantage of them. The more rational livelihood choices are those that can be made by taking into account the livelihood risks brought by tourism development.

- (2)

- Part-time livelihood type: The number of household members, the size of the labor force, and the area of forest and fruit-growing land have become the key factors that hinder the improvement of the livelihood adaptability of this type of farmer. The reason for this is that the proportion of elderly people and children supported by this type of farmer and farming family is relatively large, and the size of the labor force and the area of the forest and fruit-growing land directly determine the quality of the farming labor force and the fruit sales situation. This further affects the actual household income of this type of peasant household, which therefore restricts the possibility of comprehensive adaptive behavior in many respects.

- (3)

- Worker livelihood type: The main obstacles to the livelihood adaptation of this type of farmer are the size of the labor force, the education level of the head of household, and the social network. When the total labor force is large, the forms and structure of employment of rural households tend to be more diversified, and the possibility of employment beyond the village or in urban areas is greater; the education level of household heads affects the quality of the main labor force of their families, and highly-educated rural households often have a better livelihood. The skill level of decision-makers can determine the degree to which livelihood resources are efficiently allocated; when family members of farmers’ households are engaged as national civil servants, it encourages working beyond the farm.

- (4)

- Farming livelihood type: The area of cultivated land, forest land, and fruit-growing land and the number of family members are the main obstacles that affect the improvement of the livelihood adaptability of this type of farmer. This type of farmer is highly dependent on agricultural cultivation. The area of cultivated land, forest land, and fruit-growing land are the main factors that affect agricultural production. The size and quality of the actual area will have a significant impact on the livelihood income of this type of farmer. Their adaptation behavior is apparently also affected.

3.5. Construction of the Farmers’ Livelihood Adaptation Mechanisms

3.6. Discussion

- (1)

- Policy response: It is necessary to improve the farmers’ participation mechanism, introduce related rural tourism policies to improve the farmers’ developed awareness of farmers and the environment of rural tourism, and increase their livelihood capital stock. Specifically, these policies should support farmers’ independent entrepreneurship, help them to stay in the village, and provide support and guidance in farmhouse operation, guesthouse management, tourism restaurant/shop operations, and landscape planning. At the same time, the government itself might effectively implement tourism policy promotion and provide tourism-related technical training, enrich the forms of its training, and fully mobilize the enthusiasm of the majority of farmers to undertake further on-the-job training, thereby continuously improving their livelihood adaptability to achieve a sustainable livelihood.

- (2)

- Industry response: In order to enrich the form of farmers’ participation in tourism and increase their participation, the rural tourism industry needs to be developed and expanded. With the help of the government’s investment promotion, Ying-Tao-Gou Village may be able to increase its number of tourist attractions, routes, and characteristic agricultural and sideline products. Packaging and development efforts can promote the highlights of rural tourism and serve to form a complete industrial chain.

- (3)

- Actors’ response: As the core of adaptation, the improvement of farmers’ livelihood capabilities also requires the farmers’ efforts. Farmers may update their concepts, adjust to their development to be consistent with environmental protection, take the initiative to find employment channels, actively participate in technical training, and enhance their ability to adapt to various livelihoods.

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Su, F.J.; Kenneth, F.D.H.; Simmons, G.D. Connecting the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach and Tourism: A Review of the Literature. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2008, 15, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, T.; Wall, G. Tourism as a sustainable livelihood strategy. Tour. Manag. 2009, 1, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.X.; Huang, K.J.; Wang, X.J. Tourism Development and Rural Revitalization Based on Local Experiences: Logic and Cases. Tour. Trib. 2020, 35, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.X.; Qiu, Z.M.; Usio, N.; Nakamura, K. Tourism’s Impacts on Rural Livelihood in the Sustainability of an Aging Community in Japan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, Y.D.; Li, J.J. The multifunctional development of rural tourism and the rural sustainable livelihood: A collaborative study. Tour. Trib. 2018, 33, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- He, A.L.; Yang, X.J.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.Q. The Impact of Rural Tourism Development on Farmers’ Livelihood—A Case study of rural Tourism destinations at the northern foot of Qinling Mountains. Econ. Geogr. 2014, 34, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M.M.; Geoffrey, W.; Wang, Y.A.; Jin, M.J. Livelihood sustainability in a rural tourism destination—Hetu Town, Anhui Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Sun, Y.H.; Min, Q.W.; Jiao, W. A Community Livelihood Approach to Agricultural Heritage System Conservation and Tourism Development: Xuanhua Grape Garden Urban Agricultural Heritage Site, Hebei Province of China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoang, T.T.H.; Van Rompaey, A.; Meyfroidt, P.; Govers, G.; Vu, K.C.; Nguyen, A.T.; Hens, L.; Vanacker, V. Impact of tourism development on the local livelihoods and land cover change in the Northern Vietnamese highlands. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 22, 1371–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XI, J.C.; Zhang, N. An analysis of the sustainable livelihood of tourism households: A case study in Gougezhuang Village, Yesanpo tourism area. Tour. Trib. 2016, 31, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bires, Z.; Raj, S. Tourism as a pathway to livelihood diversification: Evidence from biosphere reserves, Ethiopia. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable rural livelihoods: A framework for analysis. In Institute of Development Studies (IDS)Working Paper; Institute of Development Studies: Falmer, UK, 1998; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Su, F.; Ying, R.R.; Zeng, J.M. Visual Analysis of Hot spots and Frontiers in Sustainable Livelihood Research. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2016, 36, 2091–2101. [Google Scholar]

- An, D.; Xu, J.C. Sustainable Livelihoods Framework: Targeting Biodiversity Conservation and Community Development in Yunnan; Yunnan Biodiversity and Traditional Knowledge Research Association: Kunming, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Si, Y.F.; Wang, L.J. The Impact of Industrial Poverty Alleviation Strategies on the Livelihoods and Household Incomes of the Rural Poor: An Empirical Analysis from Shaanxi Province. Chin. Rural Econ. 2018, 01, 78–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.T.; Wang, J.; Ding, S.J. The Dynamic Evolution of the Livelihood Model of Minority Farmers in Poor Mountain Areas—Taking Southwest Yunnan as an Example. J. South.-Cent. Univ. Natl. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2015, 35, 120–124. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, A.; Angelsen, A.; Eid, T.; Naieni, M.S.N.; Shamekhi, T. Poverty, sustainability, and household livelihood strategies in Zagros, Iran. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 79, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Pu, X.D.; Xu, Z.M.; Wang, L.A. The Relationship between Livelihood Capital and Livelihood Strategy. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2009, 19, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Yang, X.J.; Wen, X.; Deng, M.Q. The theoretical framework and demonstration of rural adaptive evolution in the context of tourism development. J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 35, 1586–1601. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, F.; Osbahr, H.; Boyd, E.; Thomalla, F.; Bharwani, S.; Ziervogel, G.; Walker, B.; Birkmann, J.; Van der Leeuw, S.; Rockström, J.; et al. Resilience and Vulnerability: Complementary or Conflicting Concepts? Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurovec, O.; Vedeld, P.O. Rural Livelihoods and Climate Change Adaptation in Laggard Transitional Economies: A Case from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wen, X.; Chen, J.; Deng, M.Q.; Yang, X.J. Study on adaptation change of farmer’s lilivlihood and the influence mechanism under tourism develop—A case study of rural tourism in YAN’AN city. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2020, 41, 250–259. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.B.; Huang, X.J.; Yang, X.J. Adaptation of land-lost farmers to rapid urbanization in urban fringe: A case study of Xi’an. Geogr. Res. 2017, 36, 226–240. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, V.P.; Babel, M.S.; Shrestha, S.; Kazama, F. A framework to assess adaptive capacity of the water resources system in Nepalese River Basins. Ecol. Indic. 2011, 11, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoddousi, S.; Pintassilgo, P.; Mendes, J. Tourism and nature conservation: A case study in Golestan National Park, Iran. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Sasaki, N.; Shivakoti, G. Effective governance in tourism development-An analysis of local perception in the Huangshan mountain area. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 112–123. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, F.D.; Tong, L.J.; Jiang, M. Adaptability assessment of industrial ecological system of mining cities in Northeast China. Geogr. Res. 2011, 30, 243–255. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Yang, H.J.; Wang, X.Y. Adaptation effect, mode and influencing factors of rural tourism:A case study of 17 typical villages in cities of Xi’an and Xianyang. J. Geogr. Res. 2019, 38, 2330–2345. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.L.; Yang, X.J. The mode and influence mechanism of rural farmers adapting to tourism development: A case study of Jinsixia in Qinling Mountains. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2013, 68, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, C.; Sasaki, N.; Jourdain, D.; Kim, S.M.; Shivakoti, P.G. Local livelihood under different governances of tourism development in China—A case study of Huangshan mountain area. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aby, S.H.; David, M.C.; Lincoln, R.L. Leveraging local livelihood strategies to support conservation and development in West Africa. Environ. Dev. 2019, 29, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, L.Q.; Yang, X.J.; Li, G. The impact of tourism development on changes of households’ livelihood and community tourism effect: A case study based on the perspective of tourism development mode. Geogr. Res. 2017, 36, 1709–1724. [Google Scholar]

- Kry, S.; Sasaki, N.; Datta, A.; Abe, I.; Ken, S.; Tsusaka, T.W. Assessment of the changing levels of livelihood assets in the Kampong Phluk community with implications for community-based ecotourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.Z.; Zhong, Z.; Yuan, M.S. The impacts of rural tourism on farmers’ livelihood—taking three tourist attractions at Hougou ancient village, Qiaojia great courtyard, and the Jinci temple of Shanxi province for example. Econ. Probl. 2008, 30, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.Y.; Huang, J.H. A Study of Hainan Rural Tourism Development Phase Division Standard—Based on Stakeholder Theory and Life Cycle Theory of Tourism Destination. J. Hebei Tour. Vocat. Coll. 2016, 21, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Yin, S.; Gebhardt, H.; Yang, X. Farmers’ livelihood adaptation to environmental change in an arid region: A case study of the Minqin Oasis, northwestern China. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 93, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.H.; Li, J.L.; Dou, Y.D. Farmers’ Livelihoods Adaptability of Rural Tourism Destinations of Edge Type Scenic Spots: Scenic Spots: A Case Study of “Great Nanyue Tourism Circle”. J. Shandong Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 21, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.S.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X.J. Farmers’ Livelihood Vulnerability and Adaptation Model in Minqin Oasis under the Arid Environment Stress. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 39, 157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.J.; Yang, S.L.; Wang, X. The relationship between livelihood capital and livelihood strategy based on logistic regression model in Xinping County of Yuanjiang dry-hot valley. Resour. Sci. 2016, 38, 136–141. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, B.; Falcol, S.D.; Lovett, J.C. Household characteristics and forest dependency: Evidence from common property forest management in Nepal. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 48, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.R.; Bao, J.G. Exploring the impacts of tourism on the livelihoods of local poor: The role of local government and major investors. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbens, M.; Schoeman, C. Planning for sustainable livelihood development in the context of rural South Africa: A micro-level approach. Town. Regi. Plan. 2020, 76, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Index | Attribute Value | Number | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 86 | 73.50% |

| Female | 31 | 26.50% | |

| Age | ≤30 years old | 7 | 5.98% |

| 31–59 years old | 67 | 57.27% | |

| ≥60 years old | 33 | 49.25% | |

| Family population | 1–2 members | 12 | 10.26% |

| 3–4 members | 47 | 40.17% | |

| 5–6 members | 51 | 43.59% | |

| 7 members or more | 7 | 5.98% | |

| Education level | Illiteracy | 23 | 19.66% |

| Primary school | 40 | 34.19% | |

| Junior school | 39 | 33.33% | |

| High school | 9 | 7.69% | |

| College and above | 6 | 5.13% | |

| Whether they participated in tourism | Yes | 51 | 43.59% |

| No | 66 | 56.41% |

| Index | First Indicator | Second Indicator | Description of Indicators | Average Value | Standard Deviation | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Livelihood adaptability | Natural capacity | Cultivated area | Land area | 2.5692 | 1.2924 | 0.0302 |

| Arable land quality | Land quality assignment:

| 3.0769 | 0.6013 | 0.0369 | ||

| Forest and fruit area | Land quality * land area | 0.8291 | 0.7012 | 0.0315 | ||

| Forest and fruit land quality | Land quality assignment:

| 3.0598 | 0.6704 | 0.0349 | ||

| Material capacity | Housing structure |

| 2.9744 | 0.9912 | 0.0433 | |

| Housing area | Housing area | 155.0256 | 72.0914 | 0.0597 | ||

| Family material asset value | The sum of the quantity and unit price of household durable goods such as beds, air conditioners, washing machines, TVs, computers, refrigerators, bicycles, electric cars, motorcycles, cars, mobile phones, etc. | 58142.4103 | 56993.5494 | 0.0676 | ||

| Ease of house reconstruction and expansion | Assignment:

| 3.0598 | 0.7876 | 0.0535 | ||

| Social capacity | Neighborhood | Assignment: Neighborhood harmony, 1 = very bad, 2 = bad, 3 = fair, 4 = good, 5 = very good | 3.8462 | 0.5936 | 0.0302 | |

| Social network | Are there any family members, relatives, or friends serving in the administrative offices of villages and towns? 1 = no, 2 = yes | 1.0941 | 0.2919 | 0.0592 | ||

| Trust in those around you | Assignment: 1 = very distrustful, 2 = relatively distrustful, 3 = fair, 4 = relatively trustful, 5 = very trustful | 3.6667 | 0.6918 | 0.0383 | ||

| Human capacity | Total household labor | Number of family laborers (farm workers aged 18–65 who are not in school and are healthy) | 2.7778 | 0.9348 | 0.0576 | |

| Educational level of head of household | Assignment: 1 = illiterate, 2 = primary, 3 = junior, 4 = high, 5 = college and above | 2.4615 | 1.0422 | 0.0500 | ||

| Total family population | Total family population (Unit: person) | 4.5213 | 1.4239 | 0.0360 | ||

| Opportunities for families to receive skills training | Assignment: 1 = very few, 2 = few, 3 = average, 4 = several, 5 = many | 2.7265 | 0.9574 | 0.0755 | ||

| Financial capacity | Family savings | Total household savings (Unit: 10,000 yuan) | 5.9854 | 5.3833 | 0.0857 | |

| Ease of borrowing | Assignment:

| 3.2649 | 0.6458 | 0.0566 | ||

| Ease of loan | Assignment:

| 3.19681 | 0.7159 | 0.0524 | ||

| Cognitive ability | Awareness of tourism policy | Assignment:

| 3.4529 | 0.7898 | 0.0420 | |

| Understanding of tourism development opportunities | Assignment:

| 3.8102 | 0.6272 | 0.0296 | ||

| Attitude towards tourism development | Assignment:

| 4.2051 | 0.5317 | 0.0294 |

| Livelihood Adaptation Types | Livelihood Adaptation Behavior | Number of Respondents | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism livelihood | Participate in tourism (operating in home stays, farmhouses, tourist shops, tourist restaurants, etc.), off-season labor/farming | 27 | 23.08% |

| Part-time livelihood | Participate in tourism (selling vegetables/selling fruits), farming/laboring | 22 | 18.80% |

| Worker livelihood | Perennial work/main work, leisure work, and agriculture | 38 | 32.48% |

| Farming livelihood | Agriculture-based and odd jobs | 30 | 25.64% |

| Livelihood Adaptation Types | Disorder Diagnosis | Barrier Factor Sorting | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism livelihood | Obstacle factors | Family savings | Home durable goods value | Family training opportunities | House area | Social network | Tourism policy awareness |

| Obstacle index | 9.48% | 7.66% | 7.55% | 7.20% | 7.09% | 6.83% | |

| Part-time livelihood | Obstacle factors | Total family population | Labor force size | Precipitation change degree | Family savings | Durable goods value | Social network |

| Obstacle index | 8.44% | 8.12% | 7.92% | 7.30% | 7.09% | 6.78% | |

| Worker livelihood | Obstacle factors | Labor force size | Educational level of head of household | Social network | Family savings | House area | Tourism policy awareness |

| Obstacle index | 10.38% | 9.12% | 8.09% | 8.00% | 7.86% | 7.76% | |

| Farming livelihood | Obstacle factors | Temperature change degree | Precipitation change degree | Total family population | Family savings | Labor force size | Home durable goods value |

| Obstacle index | 8.70% | 8.49% | 8.14% | 7.93% | 6.72% | 6.43% | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Guo, T.; Nijkamp, P.; Xie, X.; Liu, J. Farmers’ Livelihood Adaptability in Rural Tourism Destinations: An Evaluation Study of Rural Revitalization in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9544. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229544

Li H, Guo T, Nijkamp P, Xie X, Liu J. Farmers’ Livelihood Adaptability in Rural Tourism Destinations: An Evaluation Study of Rural Revitalization in China. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9544. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229544

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Huiqin, Tinghong Guo, Peter Nijkamp, Xuelian Xie, and Jingjing Liu. 2020. "Farmers’ Livelihood Adaptability in Rural Tourism Destinations: An Evaluation Study of Rural Revitalization in China" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9544. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229544