Can Leadership Transform Educational Policy? Leadership Style, New Localism and Local Involvement in Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

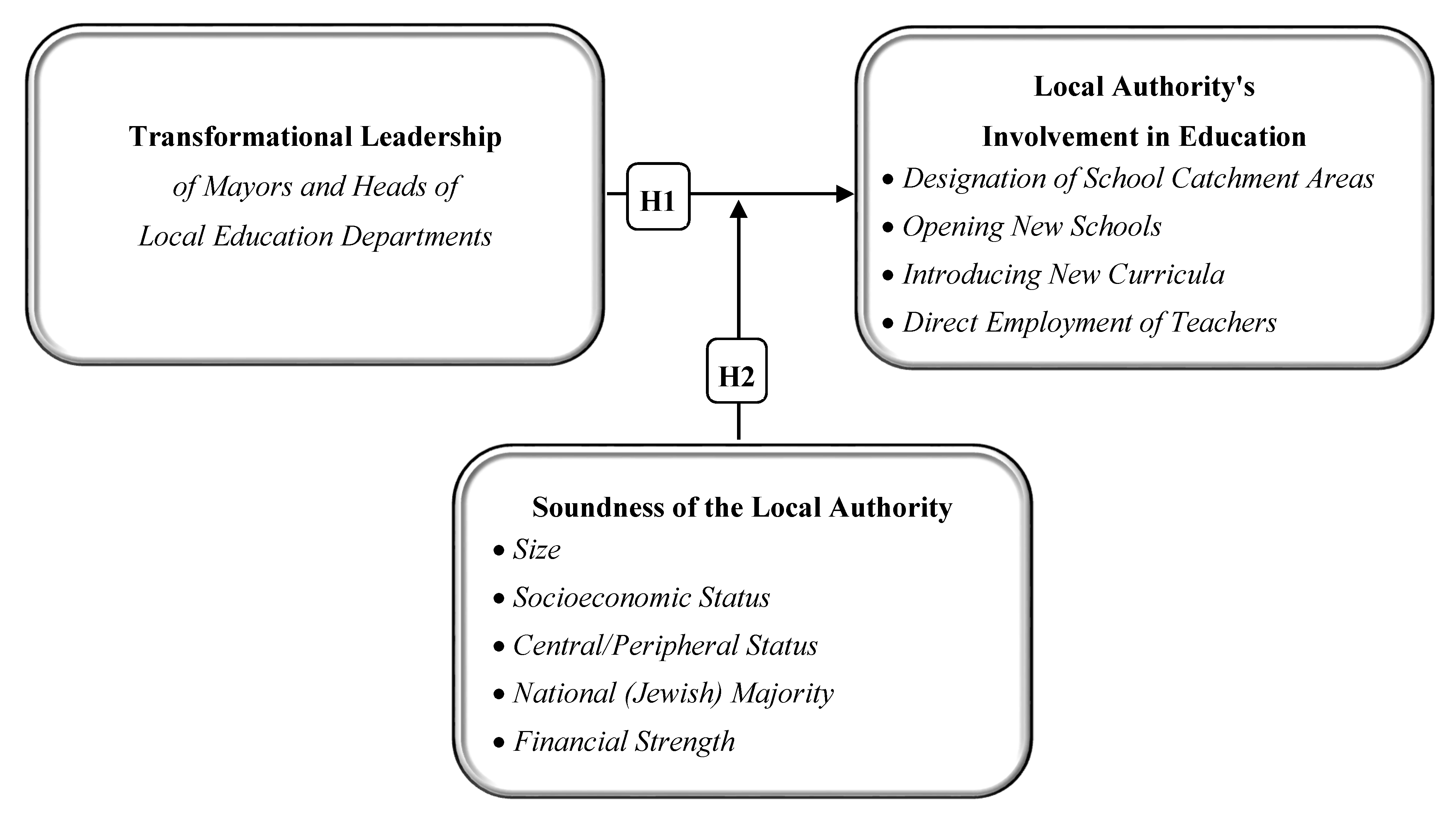

2. Localism and Education—the Research Model and Hypotheses

2.1. Localism and Education

2.2. Transformational Leadership and New Localism

3. The Soundness of Local Authorities and Their Involvement in Education

4. Method

4.1. Research Procedure, Data Collection and Sampling

4.2. Research Tool and Variables

4.2.1. Dependent Variable—Involvement in Education

- Determination of catchment areas (a responsibility granted to the local authority upon approval of the district administration).

- Establishment of new schools (doing so is under the authority of the Ministry of Education, but the Ministry is required to consult on the matter with the local authority).

- Instituting new curricula (doing so requires the approval of the Minister of Education, but the local authority is authorized to propose, opine on, and fund such changes).

- Employing teachers (while elementary teachers are employed by the Ministry of Education, the local authority may finance extra staff).

4.2.2. Independent Variable—Transformational Leadership

4.2.3. Moderating Variable—Soundness of the Local Authority

4.3. Statistical Analyses

5. Findings

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koppich, J.E.; Esch, C. Grabbing the Brass Ring. Educ. Policy 2012, 26, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galey, S. Education Politics and Policy: Emerging Institutions, Interests, and Ideas. Policy Stud. J. 2015, 43, S12–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.A.W. The new governance: Governing without government. Political Stud. 1996, 44, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, A.; Hoggett, P. Public policies, private strategies and local public spending bodies. Public Adm. 1999, 77, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovaird, T.; Löffler, E. Moving from excellence models of local service delivery to benchmarking ‘good local governance’. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2002, 68, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagley, C.; Hillyard, S. Rural schools, social capital and the Big Society: A theoretical and empirical exposition. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2014, 40, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodson, I. The educational researcher as a Public Intellectual. Br. Educ. Res. J. 1999, 25, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Ormston, C. Localism and accountability in a post-collaborative era: Where does it leave the community right to challenge? Local Gov. Stud. 2014, 40, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.M.; Perry, J.L. The transformation of governance: Who are the new public servants and what difference does it make for democratic governance? Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2013, 43, 26–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandfort, J.; Selden, S.C.; Sowa, J.E. Do government tools influence organizational performance? Examining their implementation in early childhood education. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2008, 38, 412–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Correy, D.; Stoker, G. New Localism: Refashioning the Centre-Local Relationship; New Local Government Network: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Waddock, S. Reframing and Transforming Economics around Life. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone-Johnson, C. Responsible leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 2014, 50, 645–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, C.; Brundrett, M. Leadership development and school improvement. Educ. Rev. 2009, 61, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, T. Partisan governance and policy implementation: The politics of academy conversion amongst English schools. Public Adm. 2014, 92, 995–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectation; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Improving Organizational Effectiveness through Transformational Leadership; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, J.M. Leadership; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, D. Why we need to change our concept of community leadership. Community Educ. J. 1996, 23, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J. Democr. 1995, 6, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Putnam, R. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, S.; Robison, R.A.V.; Manning, R. Delivering Social Sustainability Outcomes in New Communities: The Role of the Elected Councillor. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4920–4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leithwood, K.; Jantzi, D. A review of transformational school leadership research 1996–2005. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2005, 4, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, H.M.; Printy, S.M. Principal leadership and school performance: An integration of transformational and instructional leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 2003, 39, 370–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crowson, R.L.; Goldring, E.B. The new localism: Re-examining issues of neighborhood and community in public education. Yearb. Natl. Soc. Study Educ. 2009, 108, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, A.; Spours, K. Three version of “localism”: Implications for upper secondary education and lifelong learning in the UK. J. Educ. Policy 2012, 27, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, L. Local Governments and Regional Governance. Urban Lawyer 2007, 39, 483–528. [Google Scholar]

- Weiβ, W. Local Government Education Policy: Developments Concepts and Perspectives. 2009. Available online: http://www.difu.de/node.6861 (accessed on 10 December 2012).

- Chen, L.; Zheng, W.; Yang, B.; Bai, S. Transformational leadership, social capital and organizational innovation. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2016, 37, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daly, A.J.; Finnegan, K.S. Mind the gap: Organizational learning and improvement in an underperforming urban system. Am. J. Educ. 2012, 119, 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- Gunter, H. Leaders and Leadership in Education; Paul Chapman: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bieneman, P.D. Transformative leadership: The exercise of agency in educational leadership. Counterpoints 2011, 409, 221–237. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, C.M. Transformative leadership: Working for equity in diverse contexts. Educ. Adm. Q. 2010, 46, 558–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, C.M. Transformative Leadership in Education: Equitable and Socially Just Change in an Uncertain and Complex World; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Spillane, J.P.; Hopkins, M.; Sweet, T.M. Intra-and interschool interactions about instruction: Exploring the conditions for social capital development. Am. J. Educ. 2015, 122, 71–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Essuman, A.; Akyeampong, K. Decentralisation policy and practice in Ghana: The promise and reality of community participation in education in rural communities. J. Educ. Policy 2011, 26, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidovich, L. Global–national–local dynamics in policy processes: A case of ‘quality’ policy in higher education. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2004, 25, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coaffee, J. New localism and the management of regeneration. Int. J. Public Sector Manag. 2006, 18, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. The Third Way. The Renewal of Social Democracy; Policy Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, M.S. The rise and fall of decentralization: A comparative analysis of arguments and practices in European countries. Eur. J. Political Res. 2000, 38, 193–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckhow, S. Follow the Money: How Foundation Dollars Change Public School Politics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, M. Local solutions for national challenges? Exploring local solutions through the case of a national succession planning strategy. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2013, 41, 658–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, B.; Sellar, S.; Savage, G.C. Re-articulating social justice as equity in schooling policy: The effects of testing and data infrastructures. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2014, 35, 710–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfanz, J.; Andrekopoulos, W.; Hertz, A.; Kilman, C.T. Closing the Implementation Gap: Leveraging City Year and National Service as a New Human Capital Strategy to Transform Low-Performing Schools. New York 2012, NY City Year. Available online: https://www.cityyear.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/ClosingtheImplementationGap.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Compulsory Learning Law. No. 5709-1949. 1949. (In Hebrew)

- Gibton, D. Post-2000 law-based educational governance in Israel: From equality to diversity? Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2011, 39, 434–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Dryzin-Amit, Y. Organizational politics leadership and performance in modern public worksites: A theoretical framework. In Handbook of Organizational Politics (3–15); Vigoda-Gadot, E., Drory, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, V.K.; Huang, R.; Yayla, A.A. Social capital, collective transformational leadership, and performance: A resource-based view of self-managed teams. J. Manag. Issues 2011, 23, 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Moolenaar, N.M.; Sleegers, P.J.; Daly, A.J. Teaming up: Linking collaboration networks, collective efficacy, and student achievement. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, V.M.; Lloyd, C.A.; Rowe, K.J. The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educ. Adm. Q. 2008, 44, 635–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kerr, K.; Dyson, A.; Gallannaugh, F. Conceptualising school-community relations in disadvantaged neighbourhoods: Mapping the literature. Educ. Res. 2016, 58, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumus, S.; Bellibas, M.S.; Esen, M.; Gumus, E. A systematic review of studies on leadership models in educational research from 1980 to 2014. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2018, 46, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, R.H.; Larsen, T.J.; Marcoulides, G.A. Instructional leadership and school achievement: Validation of a causal model. Educ. Adm. Q. 1990, 26, 94–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Male, T.; Palaiologou, I. Pedagogical leadership in the 21st century: Evidence from the field. Educational Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2015, 43, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, C. Civic capacity and urban education. Urban Aff. Rev. 2001, 36, 595–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, C.A.; Floch Arcello, A.; Konrad, A.M.; Swenson, M.C. Fighting for the ‘right to the city’: Examining spatial injustice in Chicago public school closings. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2014, 35, 670–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfield, G. Tenth Annual Brown Lecture in Education Research. A new civil rights agenda for American education. Educ. Res. 2014, 43–46, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W.H.; Burroughs, N.A.; Zoido, P.; Houang, R.T. The role of schooling in perpetuating educational inequality: An international perspective. Educ. Res. 2015, 44, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gal-Arieli, N.; Beeri, I.; Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Reichman, A. New localism or fuzzy centralism: Policymakers’ perceptions of public education and involvement in education. Local Gov. Stud. 2017, 43, 598–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postholm, M.B. The school leader’s role in school-based development. Educ. Res. 2019, 61, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeri, I.; Navot, D. Local Political Corruption: Potential Structural Malfunctions at the Central-Local, Local-Local and Intra-Local Levels. Public Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 712–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeri, I.; Yuval, F. New Localism and Neutralizing Local Government: Has Anyone Bothered Asking the Public for Its Opinion? J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2015, 25, 623–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, Y. Relationship between central government and local government: Characteristics and political structures. In The Local Authority—Between the State, the Community, and the Market Economy; Levi, Y., Sarig, E., Eds.; The Open University: Raanana, Israel, 2016. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Dahan, Y.; Yona, Y. The Dovrat committee report: On the neo-liberal revolution in education. Theory Crit. 2005, 27, 11–38. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Fowles, J.; Butler, J.S.; Cowen, J.M.; Streams, M.E.; Toma, E.F. Public employee quality in a geographic context: A study of rural teachers. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2014, 44, 503–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallner, J. Legitimacy and public policy: Seeing beyond effectiveness, efficiency and performance. Policy Stud. J. 2008, 36, 421–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschall, M.; Shah, P. Keeping policy churn off the agenda: Urban education and civic capacity. Policy Stud. J. 2005, 33, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacre, H.; Hallit, S.; Hajj, A.; Zeenny, R.M.; Sili, G.; Salameh, P. The pharmacy profession in a developing country: Challenges and suggested governance solutions in Lebanon. J. Res. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eshel, S.; Hananel, R. Centralization neoliberalism, and housing policy central–local government relations and residential development in Israel. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2019, 37, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeri, I. Lack of reform in Israeli local government and its impact on modern developments in public management. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 1–13. Available online: https://doi-org.ezproxy.haifa.ac.il/10.1080/14719037.2020.1823138 (accessed on 11 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Beeri, I. Direct administration of failing local authorities: Democratic deficit or effective bureaucracy? Public Money Manag. 2020, 33, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, B.; Howell, J.M. Organizational and contextual influences on the emergence and effectiveness of charismatic leadership. Leadersh. Q. 1999, 10, 257–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A. Motivation and Personality; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

| Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Transformational leadership | 4.5 | 4 | (0.82) | |||||||||||

| 2. Size | 28.1 | 37.4 | 12 | (-) | ||||||||||

| 3. Socioeconomic status | 5.7 | 2.1 | 0.01 | −0.01 | (-) | |||||||||

| 4. Central/peripheral status | 5.6 | 1.9 | 0.22 | 0.43 ** | 0.27 ** | (-) | ||||||||

| 5. National (Jewish) majority | (-) | (-) | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.60 ** | 0.19 | (-) | |||||||

| 6. Financial strength | (-) | (-) | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.30 ** | 0.16 | 0.37 ** | (-) | ||||||

| 7. Overall soundness | 2.9 | 1.5 | 0.08 | - | - | - | - | - | (-) | |||||

| 8. Designation of school catchment areas | 2.14 | 0.47 | −0.03 | 0.25 * | −0.21 * | 0.03 | −0.14 | −0.08 | −0.06 | (0.32) | ||||

| 9. Opening new schools | 1.90 | 0.50 | 0.04 | 0.15 | −0.03 | 0.27 * | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.18 | 0.08 | (-) | |||

| 10. Introducing new curricula | 2.53 | 0.58 | 0.11 | 0.23 * | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.30 ** | 0.22 * | 0.15 | −0.11 | (0.75) | ||

| 11. Direct employment of teachers | 2.41 | 0.91 | −0.18 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.34 ** | −0.02 | 0.16 | −0.07 | −0.01 | 0.20 | (-) | |

| 12. Overall involvement in education | 2.25 | 0.40 | 0.03 | 0.35 ** | 0.07 | 0.29 ** | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.23 * | - | - | - | - | (0.75) |

| Dependent Variable | Internal Dimensions of Local Authorities’ Involvement in Education | Overall Involvement in Education | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderating Variable | Direct Hiring of Teachers | Designation of School Catchment Areas | Introducing New Curricula | Opening New Schools | ||

| Size | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | |

| Socioeconomic status | * (Model 1) | N.S. | (*) (Model 7) | N.S. | N.S. | |

| Central/peripheral status | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | |

| National (Jewish) majority | N.S. | * (Model 4) | N.S. | N.S. | * (Model 8) | |

| Financial strength | * (Model 2) | * (Model 5) | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | |

| Overall soundness | * (Model 3) | * (Model 6) | N.S. | N.S. | * (Model 9) | |

| Internal Dimensions of Local Authorities’ Involvement in Education | Overall Involvement in Education | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opening New Schools | Introducing New Curricula | Designation of School Catchment Areas | |||||||||||||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | |||||||||||

| Variables | Step1 (β) | Step2 (β) | Step1 (β) | Step2 (β) | Step1 (β) | Step2 (β) | Step1 (β) | Step2 (β) | Step1 (β) | Step2 (β) | Step1 (β) | Step2 (β) | Step1 (β) | Step2 (β) | Step1 (β) | Step2 (β) | Step1 (β) | Step2 (β) | |

| TL | 0.02 | 0.25 | −0.04 | −0.17 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.03 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.05 | |

| Soc-Eco | −0.24 | −0.30 * | −0.15 | −0.15 | |||||||||||||||

| TL X Soc-Eco | 0.46 ** | −0.32 ** | |||||||||||||||||

| National (Jewish) majority | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.09 | |||||||||||||||

| TL X National majority | 0.31 ** | 0.12 * | |||||||||||||||||

| Financial strength | −0.23 | −0.22 | −0.03 | −0.01 | |||||||||||||||

| TL X Financial strength | 0.31 * | 0.23 * | |||||||||||||||||

| Overall soundness | 0.01 | −0.06 | 15.0 | 0.10 | 0.27 * | 0.24 * | |||||||||||||

| TL X Overall soundness | 0.33 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.23 * | ||||||||||||||||

| R² | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.12 | |

| Adjusted R² | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.08 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.12 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0 | 0.09 | −0.1 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.09 | |

| ΔR² | - | 0.16 ** | - | 0.08 * | - | 0.1 * | - | 0.09 ** | - | 0.05 * | - | 0.21 *** | - | 0.09 ** | - | 0.04 | - | 0.05 * | |

| F | 1.51 | 4.49 ** | 1.32 | 2.43 | 0.01 | 1.98 | 2.42 | 4.74 ** | 0.78 | 1.90 | 1.76 | 5.28 ** | 1.05 | 3.90 * | 0.42 | 1.58 | 3.42 * | 4.02 ** | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gal-Arieli, N.; Beeri, I.; Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Reichman, A. Can Leadership Transform Educational Policy? Leadership Style, New Localism and Local Involvement in Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229564

Gal-Arieli N, Beeri I, Vigoda-Gadot E, Reichman A. Can Leadership Transform Educational Policy? Leadership Style, New Localism and Local Involvement in Education. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229564

Chicago/Turabian StyleGal-Arieli, Nivi, Itai Beeri, Eran Vigoda-Gadot, and Amnon Reichman. 2020. "Can Leadership Transform Educational Policy? Leadership Style, New Localism and Local Involvement in Education" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229564