Working with Children with ADHD—A Latent Profile Analysis of Teachers’ and Psychotherapists’ Attitudes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. The ADHD School Expectation Questionnaire (ASE)

2.3.2. Perceived Attitude towards Children with ADHD

2.3.3. Perceived Behavioral Control

2.3.4. Subjective Norm

2.3.5. Personality

2.3.6. Social Dominance Orientation (SDO)

2.3.7. Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA)

2.3.8. Stress Reactivity

2.3.9. Strain

2.3.10. Perceived Stress Elicited by Children with ADHD

2.4. Data Analysis

Latent Profile Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and MANOVA

3.2. Latent Profile Analysis

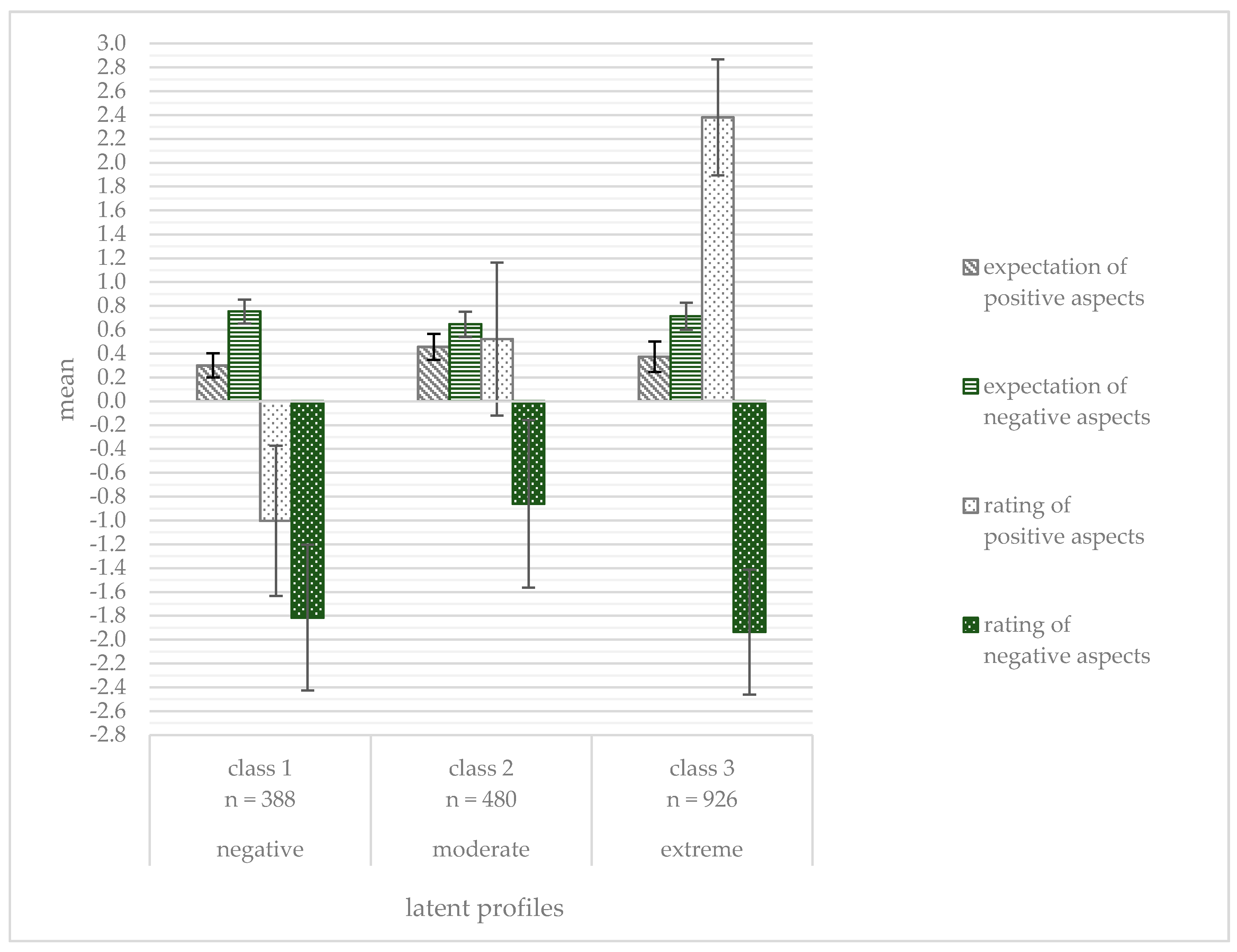

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences between PITs and Teachers

4.2. Attitude Profiles

4.3. Desirable Profile for Professionals Working with Children with ADHD

4.4. Implications

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Polanczyk, G.V.; Silva de Lima, M.; Horta, B.L.; Biederman, J.; Rohde, L.A. The Worldwide Prevalence of ADHD: A Systematic Review and Metaregression Analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanczyk, G.V.; Willcutt, E.G.; Salum, G.A.; Kieling, C.; Rohde, L.A. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: An updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, S.B.; Halperin, J.M.; Sonuga-Barke, E.J.S. A Developmental Perspective on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). In Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: New York, NY, USA; Heidelberg, Germany; Dordrecht, The Netherlands; London, UK, 2014; pp. 427–448. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D.J.; Garske, J.P.; Davis, M.K. Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattie, J. Visible Learning. A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement; Reveals Teaching’s Holy Grail. The Times Educational Supplement; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 0203887336. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, C. Lehrerfeedback und soziale Integration. Wie soziale Referenzierungsprozesse die soziale Integration in der Schule beeinflussen könnten. Empir. Sonderpädagogik 2011, 1, 20–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel, K.R. Are Effective Teachers Like Good Parents? Teaching Styles and Student Adjustment in Early Adolescence. Child Dev. 2002, 73, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, K.J.; Jones, K. Effects of Teacher Feedback on the Reputations and Peer Perceptions of Children with Behavior Problems. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2000, 76, 302–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaastra, G.F.; Groen, Y.; Tucha, L.; Tucha, O. The Effects of Classroom Interventions on Off-Task and Disruptive Classroom Behavior in Children with Symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Meta-Analytic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rohde, L.A.; Biederman, J.; Busnello, E.A.; Zimmermann, H.; Schmitz, M.; Martins, S.; Tramontina, S. ADHD in a School Sample of Brazilian Adolescents: A Study of Prevalence, Comorbid Conditions, and Impairments. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1999, 38, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, T.W.; Youngstrom, E.A.; Glutting, J.J.; Watkins, M.W. ADHD and Achievement. J. Learn. Disabil. 2007, 40, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sonuga-Barke, E.J.; Halperin, J.M. Developmental phenotypes and causal pathways in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Potential targets for early intervention? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 368–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DuPaul, G.J.; Langberg, J.M. Educational impairments in children with ADHD. In Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment: Educational Impairments in Children with ADHD, 3rd ed.; Barkley, R.A., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 169–190. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, R.; Jacobson, L. Pygmalion in the Classroom; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, R.W.; Beszterczey, S.K.; Katzenstein, T.; Park, K.; Goring, J. Are Students with ADHD More Stressful to Teach? J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2002, 10, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkasilta, J.; Vehkakoski, T.; Vehmas, S. ‘The teacher almost made me cry’ Narrative analysis of teachers’ reactive classroom management strategies as reported by students diagnosed with ADHD. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 55, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MS, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Haddock, G.; Maio, G.R. Einstellungen. In Sozialpsychologie: Eine Einführung; 6., Aufl. 2014; Jonas, K., Stroebe, W., Hewstone, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 197–229. ISBN 978-3-642-41090-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality and Behaviormapping Social Psychology, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rief, W.; Glombiewski, J.A.; Gollwitzer, M.; Schubö, A.; Schwarting, R.; Thorwart, A. Expectancies as core features of mental disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2015, 28, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. The influence of attitudes on behavior. In The Handbook of Attitudes; Albarracin, D., Johnson, B.T., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 173–222. [Google Scholar]

- Lauth, G.W.; Schlottke, P.F. Training mit Aufmerksamkeitsgestörten Kindern, 7., Vollständig überarbeitete Auflage; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2019; ISBN 3621286489. [Google Scholar]

- Spröber, N. SAVE—Strategien für Kinder und Jugendliche mit ADHS. Verbesserung der Aufmerksamkeit, der Verhaltensorganisation und Emotionsregulation; mit Online-Material; Plus Extras online; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; ISBN 9783642383618. [Google Scholar]

- Strelow, A.E.; Dort, M.; Schwinger, M.; Christiansen, H. Influences on pre-service teachers’ intention to use classroom management strategies for students with ADHD: A model analysis. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 103, 101627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Witruk, E. Teachers’ knowledge, perceived teaching efficacy, and attitudes regarding students with ADHD: A cross-cultural comparison of teachers in South Korea and Germany. Health Psychol. Rep. 2016, 2, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strelow, A.E.; Dort, M.; Schwinger, M.; Christiansen, H. Influences on in-Service teachers’ intention to use classroom management strategies for students with ADHD: A Model Replication Analysis. Int. J. Educ. Res. in preparation.

- Gaastra, G.F.; Groen, Y.; Tucha, L.; Tucha, O. Unknown, Unloved? Teachers’ Reported Use and Effectiveness of Classroom Management Strategies for Students with Symptoms of ADHD. Child Youth Care Forum 2019, 49, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dupaul, G.J.; Chronis-Tuscano, A.; Danielson, M.L.; Visser, S.N. Predictors of Receipt of School Services in a National Sample of Youth With ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2019, 23, 1303–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekle, B. Knowledge and attitudes about Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A comparison between practicing teachers and undergraduate education students. J. Atten. Disord. 2004, 7, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout and work engagement among teachers. J. Sch. Psychol. 2006, 43, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.S. Teacher Characteristics as Predictors of Teacher-Student Relationships: Stress, Negative Affect, And Self-Efficacy. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2002, 30, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekehammar, B.; Akrami, N.; Gylje, M.; Zakrisson, I. What matters most to prejudice: Big Five personality, Social Dominance Orientation, or Right-Wing Authoritarianism? Eur. J. Personal. 2004, 18, 463–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, P.; Jansen, L.J.; Schlotz, W. Stressreaktivität: Theoretisches Konzept und Messung. Diagnostica 2005, 51, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Hamrick, N.M.S.; Rodriguez, M.S.; Feldman, P.J.; Rabin, B.S.; Manuck, S.B. The stability of and intercorrelations among cardiovascular, immune, endocrine, and psychological reactivity. Ann. Behav. Med. 2000, 22, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dort, M.; Strelow, A.; Schwinger, M.; Christiansen, H. What teachers think and know about ADHD: Validation of the ADHD-school-expectation questionnaire (ASE). Int. J. Disabil. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Rammstedt, B.; Danner, D. Die Facettenstruktur des Big Five Inventory (BFI). Diagnostica 2017, 63, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohrs, J.C.; Moschner, B.; Maes, J.; Kielmann, S. The Motivational Bases of Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation: Relations to Values and Attitudes in the Aftermath of September 11, 2001. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pratto, F.; Sidanius, J.; Stallworth, L.M.; Malle, B.F. Social Dominance Orientation Scale. PsycTESTS Dataset 1994, 67, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, B.; Wolfrath, U.; Zick, A. Autoritarismus und Soziale Dominanz als generalisierte Einstellungen. Zeitschrift für Politische Psychologie 2001, 9, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Beierlein, C.; Asbrock, F.; Kauff, M.; Schmidt, P. Die Kurzskala Autoritarismus (KSA-3): Ein ökonomisches Messinstrument zur Erfassung dreier Subdimensionen autoritärer Einstellungen. Keine Angabe 2014, 35, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Schlotz, W.; Yim, I.S.; Zoccola, P.M.; Jansen, L.; Schulz, P. The perceived stress reactivity scale: Measurement invariance, stability, and validity in three countries. Psychol. Assess. 2011, 23, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franke, H. BSI. Brief Symptom Inventory von L. R. Derogatis—Deutsche Version. Kurzform der SCL-90-R (Manual); Beltz: Göttingen, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, Y.; Mendell, N.R.; Rubin, D.B. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika 2001, 88, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, G.J.; Lee, S.X.; Rathnayake, S.I. Finite Mixture Models. Annu. Rev. Stat. Its Appl. 2019, 6, 355–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, K.L.; Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B.O. Deciding on the Number of Classes in Latent Class Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling: A Monte Carlo Simulation Study. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2007, 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, E.D.; Olino, T.M. Identifying clinically distinct subgroups of self-injurers among young adults: A latent class analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abar, B.; Loken, E. Self-regulated learning and self-directed study in a pre-college sample. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2010, 20, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marsh, H.W.; Lüdtke, O.; Trautwein, U.; Morin, A.J.S. Classical Latent Profile Analysis of Academic Self-Concept Dimensions: Synergy of Person- and Variable-Centered Approaches to Theoretical Models of Self-Concept. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2009, 16, 191–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakk, Z.; Oberski, D.L.; Vermunt, J.K. Relating Latent Class Assignments to External Variables: Standard Errors for Correct Inference. Political Anal. 2014, 22, 520–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B. Auxiliary Variables in Mixture Modeling: Three-Step Approaches Using Mplus. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2014, 21, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos, J.M. Primary School Teachers’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviours toward Children with Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Ph.D. Thesis, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland, S.M.; Cumming, T.M.; Jung, J.Y. Teacher Attitudes Towards Students Who Exhibit ADHD-Type Behaviours. Australas. J. Personal. Educ. 2015, 39, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoberg, K.; Schulratgeber, A.D.H.S. Ein Leitfaden für LehrerInnen; Ernst Reinhardt Verlag: München, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, T.W.; Frenkel-Brunswik, E.; Levinson, D.; Sanford, N. The Authoritarian Personality; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg, P.Y.; Roth, M. Persönlichkeitspsychologie; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014; ISBN 978-3-531-17897-4. [Google Scholar]

| Group | N | % | Male | Female | Diverse | Age M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pre-service teachers | 1086 | 60.5 | 332 | 749 | 5 | 23.22 (3.93) |

| PIT | 109 | 6.1 | 21 | 88 | 0 | 30.94 (5.24) |

| in-service teachers | 599 | 33.4 | 106 | 493 | 0 | 41.33 (10.01) |

| Total | 1794 | 100.0 | 459 | 1330 | 5 | 29.74 (10.73) |

| Subgroup | ||||||

| pre-service_elementary school | 279 | 15.6 | 44 | 234 | 1 | 22.54 (3.92) |

| pre-service_middle school | 179 | 10.0 | 64 | 114 | 1 | 24.08 (4.48) |

| pre-service_senior high school | 488 | 27.2 | 193 | 293 | 2 | 23.16 (3.59) |

| pre-service_special needs school | 109 | 6.1 | 22 | 87 | 0 | 23.31 (3.70) |

| in-service_elementary school | 304 | 16.9 | 30 | 274 | 0 | 42.23 (9.81) |

| in-service_middle school | 157 | 8.8 | 45 | 112 | 0 | 39.52 (9.37) |

| in-service_senior high school | 42 | 2.3 | 16 | 26 | 0 | 38.24 (9.85) |

| in-service_special needs school | 56 | 3.1 | 10 | 46 | 0 | 43.59 (11.04) |

| PIT—children | 105 | 5.9 | 19 | 86 | 0 | 30.96 (5.33) |

| PIT—adults | 4 | 0.2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 30.50 (2.52) |

| Group | Attitude | Perceived Attitude | Knowledge | Use of CMS Total | Use of Effective CMS | Use of Ineffective CMS | Rating Of CMS Total | Rating of Effective CMS | Rating of Ineffective CMS | Perceived Behavioral Control | Subjective Norm | |

| pre-service teachers | M | −11.60 | −0.03 | 7.23 | 0.55 | 0.72 | 0.35 | 0.52 | 0.73 | 0.26 | 2.60 | 4.65 |

| SD | 13.92 | 1.66 | 4.21 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 1.28 | 22.50 | |

| in-service teachers | M | −13.12 | −0.20 | 9.25 | 0.57 | 0.74 | 0.36 | 0.54 | 0.76 | 0.26 | 2.82 | 11.03 |

| SD | 14.66 | 1.68 | 4.29 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 1.24 | 50.22 | |

| PIT | M | −8.84 | −0.52 | 12.57 | 0.52 | 0.81 | 0.16 | 0.53 | 0.82 | 0.17 | 3.80 | 6.39 |

| SD | 14.45 | 1.65 | 3.73 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.94 | 31.59 | |

| Total | M | −11.93 | −0.12 | 8.23 | 0.56 | 0.73 | 0.34 | 0.53 | 0.75 | 0.26 | 2.74 | 6.89 |

| SD | 14.23 | 1.67 | 4.45 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 1.28 | 34.88 | |

| Group | Extraversion | Agreeableness | Conscientiousness | Neuroticism | Openness | SDO | RWA | Stress Reactivity | Strain | Perceived Stress Elicited by Children with ADHD | ||

| pre-service teachers | M | 3.67 | 3.46 | 3.71 | 2.82 | 3.86 | 1.12 | 2.08 | 20.74 | 3.75 | 3.18 | |

| SD | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.66 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.90 | 7.40 | 0.73 | 0.98 | ||

| in-service teachers | M | 3.89 | 3.73 | 3.98 | 2.60 | 4.00 | 1.16 | 2.09 | 20.79 | 3.57 | 3.28 | |

| SD | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.94 | 7.46 | 0.63 | 1.25 | ||

| PIT | M | 3.71 | 3.83 | 3.98 | 2.62 | 3.97 | 0.99 | 1.65 | 19.31 | 3.50 | 4.11 | |

| SD | 0.72 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.57 | 0.78 | 6.04 | 0.41 | 0.67 | ||

| Total | M | 3.75 | 3.57 | 3.81 | 2.74 | 3.91 | 1.13 | 2.06 | 20.67 | 3.67 | 3.27 | |

| SD | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.91 | 7.35 | 0.69 | 1.09 | ||

| Nclasses | LogL | AIC | BIC | ssaBIC | VLMRT | LMR | BLRT | Entropy | Class Counts and Proportions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | Class 4 | |||||||||

| 1 | −10,134.896 | 20,285.793 | 20,329.730 | 20,304.315 | - | - | - | - | 1794 (100%) | |||

| 2 | −9823.516 | 19,673.032 | 19,744.431 | 19,703.131 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.855 | 1042 (58%) | 752 (42%) | ||

| 3 | −9399.986 | 18,835.973 | 18,934.833 | 18,877.648 | 0.002 | 0.003 | <0.01 | 0.855 | 388 (22%) | 480 (27%) | 926 (52%) | |

| 4 | −9239.130 | 18,524.261 | 18,650.581 | 18,577.512 | 0.450 | 0.455 | <0.01 | 0.835 | 519 (29%) | 310 (17%) | 147 (8%) | 818 (46%) |

| Expectation of Positive Aspects | Expectation of Negative Aspects | Rating of Positive Aspects | Rating of Negative Aspects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | n | z-Values M (SD) | Original Values M (SD) | z-Values M (SD) | Original Values M (SD) | z-Values M (SD) | Original Values M (SD) | z-Values M (SD) | Original Values M (SD) |

| negative | 388 | −0.605 (0.833) | 0.300 (0.101) | 0.412 (0.893) | 0.754 (0.100) | −1.429 (0.161) | −1.003 (0.629) | −0.244 (0.639) | −1.816 (0.611) |

| moderate | 480 | 0.564 (0.833) | 0.457 (0.101) | −0.492 (0.893) | 0.646 (0.106) | −0.416 (0.161) | 0.522 (0.642) | 0.975 (0.639) | −0.861 (0.704) |

| extreme | 926 | −0.046 (0.833) | 0.374 (0.128) | 0.088 (0.893) | 0.714 (0.113) | 0.826 (0.161) | 2.381 (0.486) | −0.416 (0.639) | −1.936 (0.524) |

| Class | Age M (SD) | Male | Female | Diverse | Pre-Service Teachers | in-Service Teachers | PIT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| negative | 31.48 (12.10) | 24% | 76% | 0.3% | 210 (54%/19%) | 159 (41%/27%) | 19 (5%/17%) |

| moderate | 30.45 (11.02) | 30% | 70% | 0% | 290 (60%/27%) | 163 (34%/27%) | 27 (6%/25%) |

| extreme | 28.64 (9.81) | 24% | 76% | 0.4% | 586 (63%/54%) | 277 (30%/46%) | 63 (7%/58%) |

| Class | Perceived Attitude | Knowledge | Perceived Behavioral Control | Perceived Stress | Use Ineffective CMS | Rating Effective CMS | Rating Ineffective CMS | SDO | RWA | Stress Reactivity | Extra- Version | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| negative a | −0.57 (1.67) bc | 8.65 (4.43) b | 2.57 (1.32) b | 3.53 (1.07) bc | 0.37 (0.16) bc | 0.72 (0.15) bc | 0.26 (0.14) bc | 1.23 (0.68) c | 2.24 (0.99) bc | 21.56 (8.05) b | 3.81 (0.71) c | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| moderate b | 0.51 (1.56) ac | 7.17 (4.56) ac | 3.00 (1.18) ac | 3.01 (1.08) ac | 0.33 (0.14) a | 0.74 (0.13) ac | 0.28 (0.14) ac | 1.18 (0.64) c | 1.97 (0.93) a | 19.51 (7.15) ac | 3.79 (0.69) c | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| extreme c | −0.25 (1.63) ab | 8.59 (4.37) b | 2.67 (1.29) b | 3.30 (1.07) ab | 0.34 (0.14) a | 0.76 (0.12) ab | 0.24 (0.12) ab | 1.06 (0.62) ab | 2.03 (0.86) a | 20.90 (7.08) b | 3.69 (0.69) ab | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | b | c | a | b | c | a | b | c | a | b | c | a | b | c | a | b | c | a | b | c | a | b | c | a | b | c | a | b | c | a | b | c | |

| negative a | - | 0.7 | 0.2 | - | 0.3 | - | 0.3 | 0.3 | - | 0.5 | 0.2 | - | 0.3 | 0.2 | - | 0.1 | 0.3 | - | 0.1 | 0.2 | - | 0.3 | - | 0.3 | 0.2 | - | 0.3 | - | 0.2 | ||||

| moderate b | 0.7 | - | 0.5 | 0.3 | - | 0.3 | 0.3 | - | 0.5 | - | 0.3 | 0.3 | - | 0.1 | - | 0.2 | 0.1 | - | 0.3 | - | 0.2 | 0.3 | - | 0.3 | - | 0.2 | - | 0.1 | |||||

| extreme c | 0.2 | 0.5 | - | 0.3 | - | 0.3 | - | 0.2 | 0.3 | - | 0.2 | - | 0.3 | 0.2 | - | 0.2 | 0.3 | - | 0.3 | 0.2 | - | 0.2 | - | 0.2 | - | 0.2 | 0.1 | - | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dort, M.; Strelow, A.E.; Schwinger, M.; Christiansen, H. Working with Children with ADHD—A Latent Profile Analysis of Teachers’ and Psychotherapists’ Attitudes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9691. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229691

Dort M, Strelow AE, Schwinger M, Christiansen H. Working with Children with ADHD—A Latent Profile Analysis of Teachers’ and Psychotherapists’ Attitudes. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9691. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229691

Chicago/Turabian StyleDort, Martina, Anna Enrica Strelow, Malte Schwinger, and Hanna Christiansen. 2020. "Working with Children with ADHD—A Latent Profile Analysis of Teachers’ and Psychotherapists’ Attitudes" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9691. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229691