Social Entrepreneurship Education as an Innovation Hub for Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: The Case of the KAIST Social Entrepreneurship MBA Program

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Basis

2.1. Social Entrepreneurship Education (SEE)

2.2. Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (EE)

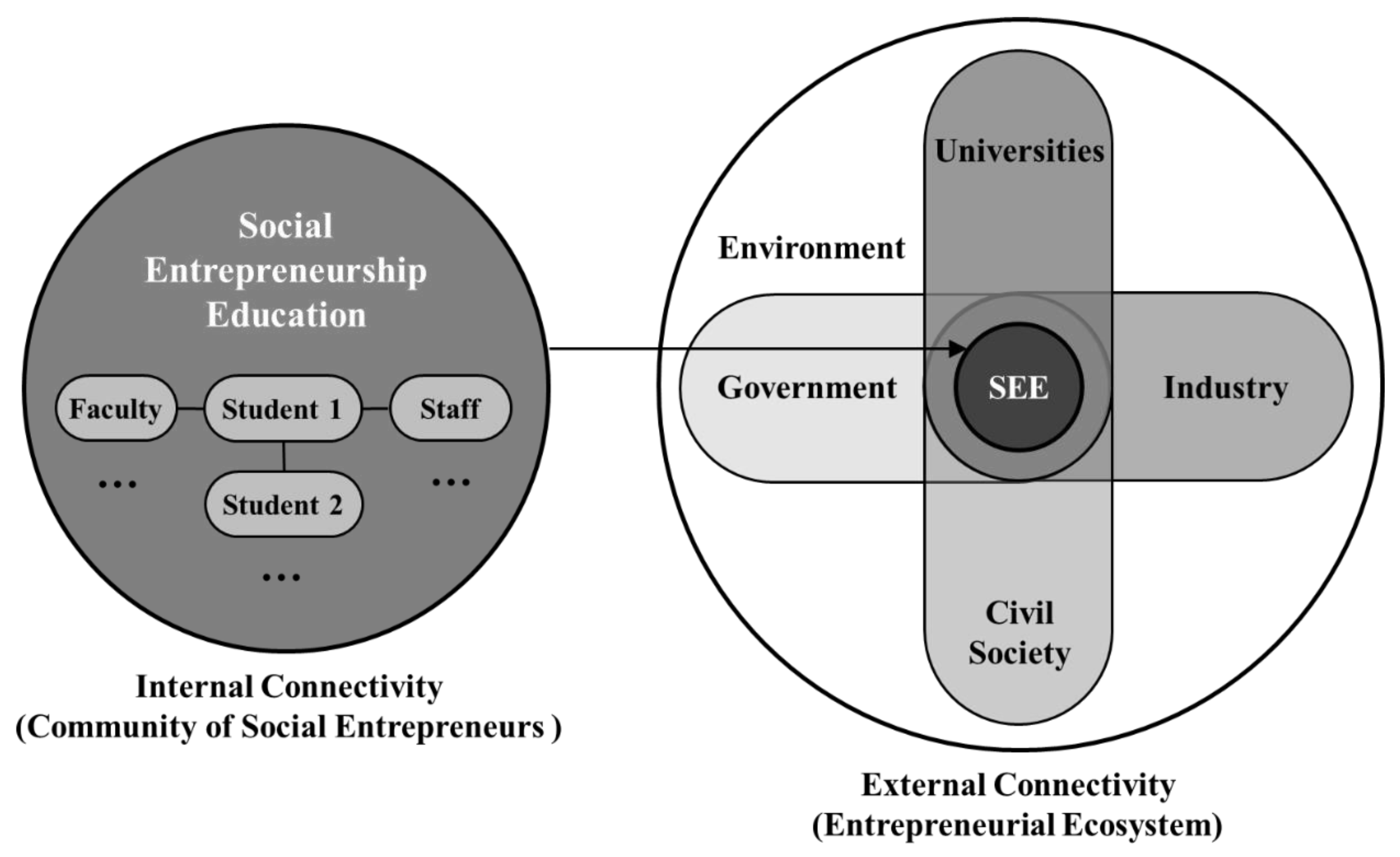

2.3. SEE Design Framework

3. The Case: KAIST Social Entrepreneurship MBA Program (KSEMP)

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. The History and Status of KSEMP

3.3. Social Enterprise Ecosystem in Korea

4. KSEMP as an Innovation Hub for the Social Enterprise Ecosystem

4.1. Internal Connectivity

4.1.1. The Community of Student Entrepreneurs

4.1.2. Student–Faculty Relationships

4.1.3. Student–Staff Relationships

4.2. External Connectivity

4.2.1. University

4.2.2. Government

4.2.3. Industry

4.2.4. Civil Society

4.2.5. Environment

4.3. Strengthening the Connectivity

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Organizations | Website Address |

|---|---|

| KAIST | kaist.ac.kr |

| KAIST College of Business | business.kaist.ac.kr |

| SK Centre for Social Entrepreneurship | sksecenter.kaist.ac.kr |

| KAIST College of Business Start-up | kcbstartup.kaist.ac.kr |

| Start-up KAIST | startup.kaist.ac.kr |

| KAIST K-School | kschool.kaist.ac.kr |

| KSEMP (official brochure) | business.kaist.ac.kr/_prog/brochure/download.php?mng_no=3&site_dvs_cd=kr |

| Interviewees (N = 22) | Gender | Female | 2 |

| Male | 20 | ||

| Age | Evenly distributed from 30 s to 60 s | ||

| Job | Professor | 8 | |

| CEO | 8 | ||

| Corporate Executive | 2 | ||

| Corporate Employee | 1 | ||

| NGO Executive | 1 | ||

| NGO Employee | 2 | ||

| Length | About 60–80 min | ||

| Language | Korean | ||

| Question type | Open-ended question | ||

References

- Howorth, C.; Smith, S.M.; Parkinson, C. Social learning and social entrepreneurship education. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2012, 11, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M.R.; Porter, M.E. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, P.L. The evolution of corporate social responsibility. Bus. Horiz. 2007, 50, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chell, E. Social enterprise and entrepreneurship: Towards a convergent theory of the entrepreneurial process. Int. Small Bus. J. 2007, 25, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chell, E.; Nicolopoulou, K.; Karataş-Özkan, M. Social entrepreneurship and enterprise: International and innovation perspectives. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, T.; Vaccaro, A. Stakeholders matter: How social enterprises address mission drift. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, B.; Haugh, H.; Lyon, F. Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jenner, P.; Florin, O. The sectorial trust of social enterprise: Friend or foe? J. Soc. Entrep. 2016, 7, 236–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, P.N.; Smith, B.R. Identifying the drivers of social entrepreneurial impact: Theoretical development and an exploratory empirical test of SCALERS. J. Soc. Entrep. 2010, 1, 126–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.S. Conceptualizing the international for-profit social entrepreneur. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockerts, K. The effect of experiential social entrepreneurship education on intention formation in students. J. Soc. Entrep. 2018, 9, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youtie, J.; Shapira, P. Building an innovation hub: A case study of the transformation of university roles in regional technological and economic development. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 1188–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T.L. A holistic person perspective in measuring entrepreneurship education impact—Social entrepreneurship education at the Humanities. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2014, 12, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, D.D.; Steiner, S. Social entrepreneurship education: Is it achieving the desired aims? SSRN Electron. J. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, P.; Phillips, N. The distinctive challenge of educating social entrepreneurs: A postscript and rejoinder to the special issue on entrepreneurship education. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2007, 6, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T.; Phillips, N.; Tracey, P. From the guest editors: Educating social entrepreneurs and social innovators. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2012, 11, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Rooney, D.; Phillips, N. Practice-based wisdom theory for integrating institutional logics: A new model for social entrepreneurship learning and education. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2016, 15, 607–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, D.; Ibrahim, N. The case for (Social) entrepreneurship education in Egyptian Universities. J. Educ. Train. 2011, 53, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobele, L. A new approach in higher education: Social entrepreneurship education. In Volume of Management, Enterprise and Benchmarking in the 21st Century III; Michelberger, P., Ed.; Óbuda University: Budapest, Hungary, 2016; pp. 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Pache, A.-C.; Chowdhury, I. Social entrepreneurs as institutionally embedded entrepreneurs: Toward a new model of social entrepreneurship education. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2012, 11, 494–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bahrami, H.; Evans, S. Flexible re-cycling and high-technology entrepreneurship. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1995, 37, 62–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritz, A.; Koch, A.; Schmidt, M. The role of entrepreneurship education programs in national systems of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship ecosystems. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 2016, 8, 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Spilling, O.R. The entrepreneurial system: On entrepreneurship in the context of a mega-event. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigel, B. The relational organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrep. Theory Prac. 2017, 41, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freeman, C. Technological infrastructure and international competitiveness. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2004, 13, 541–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edquist, C. Systems of innovation: Perspectives and challenges. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2010, 2, 14–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundvall, B.Å. National innovation systems—Analytical concept and development tool. Ind. Innov. 2007, 14, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Clusters and the new economics of competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, J.S.; del-Palacio, I. Global networks of clusters of innovation: Accelerating the innovation process. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 52, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarysse, B.; Wright, M.; Bruneel, J.; Mahajan, A. Creating value in ecosystems: Crossing the chasm between knowledge and business ecosystems. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1164–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, A.N.; Scott, J.T. US science parks: The diffusion of an innovation and its effects on the academic missions of universities. In Universities and the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem; Audretsch, D.B., Link, A.N., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Whittington, K.B.; Owen-Smith, J.; Powell, W.W. Networks, propinquity, and innovation in knowledge-intensive industries. Adm. Sci. Q. 2009, 54, 90–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baptista, R. Clusters, innovation and growth: A survey of the literature. In The Dynamics of Industrial Clusters: International Comparisons in Computing and Biotechnology; Swann, G.M.P., Prevezer, M., Stout, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 13–51. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.F. Predators and prey: A new ecology of competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Isenberg, D. The big idea: How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, 88, 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Adner, R. Match your innovation strategy to your innovation ecosystem. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feld, B. Startup Communities: Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Your City; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roundy, P.T.; Bradshaw, M.; Brockman, B.K. The emergence of entrepreneurial ecosystems: A complex adaptive systems approach. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster, E.; Padilla-Meléndez, A.; Lockett, N.; del-Águila-Obra, A.R. The emerging role of university spin-off companies in developing regional entrepreneurial university ecosystems: The case of Andalusia. Technol. For. Soc. Chang. 2019, 141, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carree, M.; Malva, A.D.; Santarelli, E. The contribution of universities to growth: Empirical evidence for Italy. J. Technol. Transf. 2014, 39, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guerrero, M.; Urbano, D.; Cunningham, J.; Organ, D. Entrepreneurial universities in two European regions: A case study comparison. J. Technol. Transf. 2014, 39, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayter, C.S. A trajectory of early-stage spinoff success: The role of knowledge intermediaries within an entrepreneurial university ecosystem. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 47, 633–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubik, S.; Garnsey, E.; Minshall, T.; Platts, K. Value creation from the innovation environment: Partnership strategies in university spin-outs. R&D Manag. 2013, 43, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Kenney, M.; Mustar, P.; Siegel, D.; Wright, M. Entrepreneurial innovation: The importance of context. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Cross, R. A relational view of information seeking and learning in social networks. Manag. Sci. 2003, 49, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Braunerhjelm, P.; Audretsch, D.B.; Carlsson, B. The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2009, 32, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayter, C.S. Conceptualizing knowledge-based entrepreneurship networks: Perspectives from the literature. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 41, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, C.; Heidl, R.; Wadhwa, A. Knowledge, networks, and knowledge networks: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1115–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bacq, S.; Eddleston, K.A. A resource-based view of social entrepreneurship: How stewardship culture benefits scale of social impact. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharir, M.; Lerner, M. Gauging the success of social ventures initiated by individual social entrepreneurs. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, E.; Carter, S. Social entrepreneurship: Theoretical antecedents and empirical analysis of entrepreneurial processes and outcomes. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2007, 14, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Engel, J.S.; del-Palacio, I. Global clusters of innovation: The case of israel and silicon valley. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 53, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Grigoroudis, E.; Campbell, D.F.J.; Meissner, D.; Stamati, D. The ecosystem as helix: An exploratory theory-building study of regional co-opetitive entrepreneurial ecosystems as quadruple/quintuple helix innovation models. R&D Manag. 2018, 48, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F.J. Triple helix, quadruple helix and quintuple helix and how do knowledge, innovation and the environment relate to each other? A proposed framework for a trans-disciplinary analysis of sustainable development and social ecology. Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 1, 41–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Barth, T.D.; Campbell, D.F.J. The Quintuple Helix innovation model: Global warming as a challenge and driver for innovation. J. Innov. Entrep. 2012, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Employment and Labor. The 3rd Basic Plan for Social Enterprise Promotion (2018–2022); Ministry of Employment and Labor: Sejong City, Korea, 2018.

- Son, H.; Lee, J.; Chung, Y. Value creation mechanism of social enterprises in manufacturing industry: Empirical evidence from Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- OECD. Boosting Social Enterprise Development: Good Practice Compendium; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Prasetyo, A.H.; Lo, W.; Chang, A. Network model for social entrepreneurships: Pathways to sustainable competitive advantage. J. Small Bus. Entrep. Dev. 2016, 4, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Motoyama, Y.; Knowlton, K. Examining the connections within the startup ecosystem: A case study of St. Louis. Entrep. Res. J. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Perspectives | Authors | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Educational content | Jensen [13] | SEE teaches students to work with private and public partners to create social value in innovative ways. |

| Brock and Steiner [14] | SEE deals with how to start a social enterprise and make it sustainable. | |

| Tracey and Phillips [15] | SEE focuses on creating social value by reorganizing human and other resources. | |

| Educational methods | Howorth et al. [1] | Learning from peers is more important than thinking-based learning for fostering social entrepreneurship. |

| Hockerts [11] | The empirical learning process is critical to increase the tendency of students to establish social enterprises. | |

| Zhu et al. [17] | They designed a curriculum matrix for developing a sustainable business model of social enterprises. | |

| Educational performance | Kirby and Ibrahim [18] | SEE can improve students’ awareness of and attitudes toward social entrepreneurship as a career option. |

| Dobele [19] | SEE is essential not only for sustainable social structures, but also for the personal development of individuals. | |

| Pache and Chowdhury [20] | SEE extends an individual’s competence in capturing and evaluating entrepreneurial opportunities. |

| Sources | Description |

|---|---|

| Public promotion materials * | Based on the following public information describing the KSEMP, the authors described what activities for internal/external connectivity the KSEMP has performed and with whom.

|

| Internal operational information | Based on the following inside information, the authors reviewed what activities for internal/external connectivity the KSEMP has performed and planned to perform and with whom. Only the activities and entities that are explicitly mentioned in the following information are addressed.

|

| Interviews ** and surveys | From the results of interviews, surveys, and consultation with various stakeholders, the authors endeavored to interpret the context of the explicitly described information. The following concerns the participants in the interviews (9 July to 5 October 2018) and surveys (2 to 7 August 2018).

|

| Courses | Subjects (Credits) | Main Classes |

|---|---|---|

| Mandatory Major | Social Entrepreneurship (22.5/48 *) | Social Venture Lean Start-up Social Issue Analysis and Mission Development Social Entrepreneurship Social Venture Ideation Social Venture Business Model |

| Business Management (12/48) | Leadership and Organization Management Marketing Financial Management Supply Chain Management | |

| Mandatory General | Statistics (3/48) | Probability and Statistics |

| Elective /Research | Others (10.5/48) | Special Topics in Social Enterprises Seminar for Social Enterprises Field Study in Social Enterprise ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, M.G.; Lee, J.-H.; Roh, T.; Son, H. Social Entrepreneurship Education as an Innovation Hub for Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: The Case of the KAIST Social Entrepreneurship MBA Program. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9736. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229736

Kim MG, Lee J-H, Roh T, Son H. Social Entrepreneurship Education as an Innovation Hub for Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: The Case of the KAIST Social Entrepreneurship MBA Program. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9736. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229736

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Moon Gyu, Ji-Hwan Lee, Taewoo Roh, and Hosung Son. 2020. "Social Entrepreneurship Education as an Innovation Hub for Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: The Case of the KAIST Social Entrepreneurship MBA Program" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9736. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229736