Modeling Cross-National Differences in Automated Vehicle Acceptance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Possible Impacts of AV Assimilation

2.2. Understanding Attitudes towards AVs

3. Methodology

3.1. Survey Design and Administration

- Using a Privately owned Regular Car similar to conventional private cars used today.

- Using a Privately owned Automated Vehicle. This option is similar to Privately owned Regular Cars, but it could be a different type and size vehicle. This vehicle will drive itself without a human driver and will leave you at your destination, to then park itself.

- Using a Shared Automated Vehicle which you do not own. You will be able to travel in it just by yourself (shared vehicle) or to travel with strangers (shared ride). If you choose to share it with others, you may save some money. However, on some occasions you will waste time picking up and dropping off other passengers. Occasionally, you will be able to travel faster on special road lanes, for high occupancy vehicles, and save time traveling.

3.2. The Logit Kernel Model

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Modal Split and Choice Patterns

4.3. Parameter Estimates

4.4. Models Parameters Inference

4.5. Value of Time Analysis

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Study Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Payre, W.; Cestac, J.; Delhomme, P. Intention to use a fully automated car: Attitudes and a priori acceptability. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2014. [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SAE International. SAE International’s Levels of Driving Automation for on-Road Vehicles. Available online: http://www.sae.org/misc/pdfs/automated_driving.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Guo, J.; Susilo, Y.; Antoniou, C.; Brenden, A.P. Influence of individual perceptions on the decision to adopt automated bus services. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milakis, D. Long-term implications of automated vehicles: An introduction. Transp. Rev. 2019, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milakis, D.; van Arem, B.; van Wee, B. Policy and society related implications of automated driving: A review of literature and directions for future research. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soteropoulos, A.; Berger, M.; Ciari, F. Impacts of automated vehicles on travel behaviour and land use: An international review of modelling studies. Transp. Rev. 2019, 39, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadud, Z.; MacKenzie, D.; Leiby, P. Help or hindrance? The travel, energy and carbon impacts of highly automated vehicles. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 86, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomopoulos, N.; Givoni, M. The autonomous car—A blessing or a curse for the future of low carbon mobility? An exploration of likely vs. desirable outcomes. Eur. J. Futures Res. 2015, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koul, S.; Eydgahi, A. Utilizing technology acceptance model (Tam) for driverless car technology adoption. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2018, 13, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schoettle, B.; Sivak, M. Public Opinion About Self-Driving vehicles in China, India, Japan, the U.S., the U.K., and Australia; The University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Westjohn, S.; Arnold, M.J.; Magnusson, P.; Zdravkovic, S.; Zhou, J.X. Technology readiness and usage: A global-identity perspective. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2009, 37, 250–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haboucha, C.J.; Ishaq, R.; Shiftan, Y. User preferences regarding autonomous vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milakis, D.; Thomopoulos, N.; van Wee, B. Policy Implications of Autonomous Vehicles; Advances in Transport Policy and Planning Book Series; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, M.; Motamedidehkordi, N.; Krause, S.; Hoffmann, S.; Vortisch, P.; Busch, F. Impact of Autonomous Vehicles on Capacity of the German Freeway Network. In Proceedings of the ITS World Congress, Montreal, QC, Canada, 29 October–2 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, S.; Chaniotakis, E.; Antoniou, C. Factors affecting traffic flow efficiency implications of connected and autonomous vehicles: A review and policy recommendation. Adv. Transp. Policy Plan. 2020, 5, 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Le Vine, S.; Zolfaghari, A.; Polak, J.W. Autonomous cars: The tension between occupant experience and intersection capacity. Transp. Res. Part C 2015, 52, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H. Verkehrsplanung für das Zeitalter des Autonomen Fahrens; Presentation; VöV: Lugano, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hamadneh, J.; Esztergár-Kiss, D. Impacts of Shared Autonomous Vehicles on Travelers’ Mobility. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Models and Technologies for Intelligent Transportation Systems, Cracow, Poland, 5–7 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manser, P.; Becker, H.; Hörl, S.; Axhausen, K.W. Designing a large-scale public transport network using agent-based microsimulation. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 137, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvarsson, A.B.; Martani, C.; Adey, B.T. Considering automated vehicle deployment uncertainty in the design of optimal parking garages using real options. J. Build. Eng. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.; Becker, H.; Bösch, P.M.; Axhausen, K.W. Impact of Autonomous Vehicles on the Accessibility in Switzerland; Arbeitsberichte Verkehrs-und Raumplanung, 1177, IVT; ETH Zürich: Zürich, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fraedrich, E.; Heinrichs, D.; Bahamonde-Birke, F.J.; Cyganski, R. Autonomous driving, the built environment and policy implications. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 122, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kröger, L.; Kuhnimhof, T.; Trommer, S. Does context matter? A comparative study modelling autonomous vehicle impact on travel behaviour for Germany and the USA. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 122, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagnant, D.J.; Kockelman, K.M. Preparing a nation for autonomous vehicles: Opportunities, barriers and policy recommendations. Transp. Res. Part A 2015, 77, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Urban mobility system upgrade: How shared self-driving cars could change city traffic. Corp. Partnersh. Board Rep. 2020, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, W.; Guhathakurta, S.; Fang, J.; Zhang, G. Exploring the impact of shared autonomous vehicles on urban parking demand: An agent-based simulation approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2009, 19, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Choudhury, C.F.; Ben-Akiva, M.; Silva, J.A.; Carvalho, D. Stated Preference Survey for New Smart Transport Modes and Services: Design, Pilot Study and New Revision 2009, MIT Portugal. Available online: http://www.mitportugal.org/ (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Becker, F.; Axhausen, K.W. Literature review on surveys investigating the acceptance of autonomous vehicles. Transportation 2017, 44, 1293–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gurumurthy, K.M.; Kockelman, K.M. Modeling Americans’ autonomous vehicle preferences: A focus on dynamic ride-sharing, privacy and long-distance mode choices. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 150, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakatos, A.; Mándoki, P. Mode-choice analysis in long-distance, parallel public transport. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 44, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiftan, Y.; Burd-Eden, R. Modeling Response to Parking Policy. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2001, 1765, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhong, H.; Li, W.; Burris, M.W.; Talebpour, A.; Sinha, K.C. Will autonomous vehicles change auto commuters’ value of travel time? Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 83, 102303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, T.U.; Burris, M.; Labi, S.; Sinha, K.C. An empiricial discourse on forecasting the use of autonomous vehicles using consumers’ preferences. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 158, 120130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkrof, P.; de Correia, G.H.A.; Cats, O.; van Arem, B. Impact of automated vehicles on travel mode preference for different trip purposes and distances. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019, 2673, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Correia, G.H.; Looff, E.; van Cranenburgh, S.; Snalder, M.; van Arem, B. On the impact of vehicle automation on the value of travel time while performing work and leisure activities in a car: Theoretical insights and results from a stated preference survey. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 119, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lavieri, P.S.; Bhat, C.R. Modeling individuals’ willingness to share trips with strangers in an autonomous vehicle future. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 124, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolarova, V.; Steck, F.; Cyganski, R.; Trommer, S. Estimation of the value of time for automated driving using revealed and stated preference methods. Transp. Res. Procedia 2018, 31, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, F.; Axhausen, K.W. Predicting the Use of Automated Vehicles [First Results from the Pilot Survey]. In Proceedings of the 17th Swiss Transport Research Conference, Ascona, Switzerland, 17–19 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R.; Rashidi, T.; Rose, J. Preferences for shared autonomous vehicles. Trans. Res. Part C 2016, 69, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidis, M.; Happee, R.; de Winter, J.C.F. Public opinion on automated driving: Results of an international questionnaire among 5000 respondents. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2015, 32, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. Global Automative Consumer Study: Advanced Vehicle Technologies and Multimodal Transportation; Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. Reshaping Urban Mobility with Autonomous Vehicles: Lessons from the City of Boston, White Paper; Boston Consulting Group: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Anania, E.C.; Rice, S.; Walters, N.W.; Pierce, M.; Winter, S.R.; Milner, M.N. The effects of positive and negative information on consumers’ willingness to ride in driverless vehicle. Transp. Policy 2018, 72, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šinko, S.; Knez, M.; Obrecht, M. Analysis of Public Opinion on Autonomous Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Challenges of Europe: Innovative Responses for Resilient Growth and Competitiveness, Bol, Croatia, 17–19 May 2017; pp. 219–230. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, T.; Cavoli, C. Automated vehicles: Exploring possible consequences of government (non)intervention for congestion and accessibility. Transp. Rev. 2019, 39, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hulse, L.M.; Xie, H.; Galea, E.R. Perceptions of autonomous vehicles: Relationships with road users, risk gender and age. Soc. Sci. 2018, 102, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csuka, S.I.; Martos, T.; Kapornaky, M.; Sallay, V.; Lewis, C.A. Attitudes toward technologies in the near future: The role of Technology Readiness in a Hungarian adult sample. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2019, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.L.; Wang, Y.; Thorhauge, M.; Ben-Akiva, M. D-efficient or deficient? A robustness analysis of stated choice experimental designs. Theory Decis. 2018, 84, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ben-Akiva, M.; Bolduc, D.; Walker, J. Specification, Identification and Estimation of the Logit Kernel (or Continuous Mixed Logit) Model. 2001. Available online: http://emlab.berkeley.edu/reprints/misc/multinomial2.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Train, K.E. Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cunningham, M.L.; Regan, M.A.; Ledger, S.A.; Bennett, J.M. To buy or not to buy? Predicting willingness to pay for automated vehicles based on public opinion. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 65, 418–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Tanishita, M.; Matsuzaki, T. Meta-Analysis of Value of Travel Time Savings: Evidence from Japan. In Proceedings of the 12th World Conference on Transport Research, Lisbon, Portugal, 11–15 July 2010; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wardman, M.; Chintakayala, V.P.K.; de Jong, G. Values of travel time in Europe: Review and meta-analysis. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 94, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. European Statistics, Database. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Bierlaire, M. A Short Introduction to PandasBiogeme; Technical Report TRANSP-OR 200605; Transport and Mobility Laboratory, Ecole Polytechnique F’ed´erale de Lausanne: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hohenberger, C.; Spörrle, M.; Welpe, I.M.; Hohenberger, C.; Spörrle, M.; Welpe, I.M. How and why do men and women differ in their willingness to use automated cars? The influence of emotions across different age groups. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 94, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Data. GDP Per Capita, 2020. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Singleton, P.A. Discussing the “positive utilities” of autonomous vehicles: Will travellers really use their time productively? Transp. Rev. 2019, 39, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steck, F.; Kolarova, V.; Bahamonde-Birke, F.; Trommer, S.; Lenz, B. How autonomous driving may affect the value of travel time savings for commuting. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barbour, N.; Menon, N.; Zhang, Y.; Mannering, F. Shared Automated Vehicles: A Statistical Analysis of Consumer Use Likelihoods and Concerns. Transp. Policy 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Expectations and Concerns from a Connected and Automated Mobility; Special Eurobarometer 496; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Swait, J.; Louviere, J.J.; Williams, M. A sequential approach to exploiting the combined strength of stated preference and revealed-preference data: Application to the freight shipper choice. Transportation 1994, 21, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, K.; Oded, C.; Martens, K.; van Arem, B. Stated choice experiment on mode choice in an era of free-floating carsharing and shared autonomous vehicles: Raw data. Transp. Res. Board 2017, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D.A. How do respondents process stated choice experiments? Attribute consideration under varying information load. J. Appl. Econom. 2006, 47, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E. Beyond the ABC: Climate change policy and theories of social change. Environ. Plan. A 2019, 42, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Source | Choice Set | Variables Studied | Country of Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| [29] | AV, SAV, or airplane long-distance travel | Travel time, travel cost, socio-demographics | USA |

| [32] | AV or SAV | Travel time, travel cost, urban, suburban and rural residence | USA |

| [33] | Traditional vehicle, privately-owned AV, hired AV, shared AV service | Socio-demographics, location | USA |

| [34] | Conventional car, public transportation, automated driving transport service | Travel time, waiting time, walking time, cost | Netherlands |

| [35] | AV with office interior, AV with leisure interior, conventional car | Travel time, travel cost, and effect on value of travel time savings | Netherlands |

| [36] | Private AV, shared AV | Number of passengers, additional travel time, discount, fare structure, travel time | USA |

| [37] | Walk, bicycle, public transport, private AV, shared AV | Trip duration, access/egress time, waiting time, ridesharing (yes/no), travel costs | Germany |

| [38] | Train + AV, Train + SAV, SAV, AV, conventional vehicle | Travel time, access/egress time, waiting time, number of changes, service frequency, travel cost | Switzerland |

| [12] | Regular car, private AV, shared AV | Travel cost, travel time, attitudes | Israel/North America |

| [39] | SAV without ride sharing, SAV with ride sharing, current mode choice | Travel cost, travel time, waiting time | Australia |

| Source | Question Posed | Sample Size and Location | Response | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10] | “What is your general opinion regarding autonomous and self-driving vehicles?” | N = 1′533 China, India, Japan, USA., UK, and Australia | 56.8% positive or rather positive | 5-point Likert scale from Negative to Positive |

| [40] | “Fully automated driving will be enjoyable.” | N = 4′838 Netherlands | 56.3% agrees or strongly agrees | 5-point Likert scale from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree |

| [42] | “Would you take a ride in a fully self-driving car?” | N = 5′500 27 cities in China, France, Germany, India, Japan, Netherlands, Singapore, UAE, UK and USA | 58% likely or very likely | 5-point Likert scale from Very unlikely to very likely |

| [41] | “To what extent do you believe that fully self-driving cars will not be safe?” | N = 10′345 USA, Germany, India, Japan, Republic of Korea and China | 47%–50% agree or strongly agree (results only shown by country). China is outlier with 25%. | 5-point Likert scale from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree |

| Country | Source | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Slovenia | [44] | Based on a national survey sample. Purchase intentions of AVs. Finds that public opinion towards AVs is more negative in Slovenia than elsewhere |

| Cyprus | n/a | AV acceptance has not been tested in Cyprus before this study. |

| UK | [45] | Using deliberative workshops, came to conclusion that with a regulated market, more socially desirable outcomes will be realized. |

| [46] | AVs considered a somewhat low risk. While skepticism was present amongst respondents, there was little opposition for AV using existing road infrastructure. | |

| Hungary | [47] | Using technology readiness to relate attitudes with acceptance of technology. Generally, optimism was an influencing factor on acceptance. |

| Iceland | n/a | AV acceptance has not been tested in Iceland before this study. |

| Montenegro | n/a | AV acceptance has not been tested in Montenegro before this study. |

| Private Regular Car | Private Automated Car | Ride Sharing/Car Sharing in an Automated Car | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trip cost | 0.7 × T × C | 0.9 × T × C | 0.5 × T × C |

| 1 × T × C | 1.2 × T × C | 0.8 × T × C | |

| 1.3 × T × C | 1.5 × T × C | 1.1 × T × C | |

| Travel time (D2D) | 1 × T | 0.8 × T | 0.7 × T |

| 1.2 × T | 1 × T | 1 × T | |

| 1.4 × T | 1.2 × T | 1.3 × T | |

| 1.6 × T | 1.4 × T | 1.6 × T | |

| Number and gender of passengers ridesharing respondent | N.A | N.A | Just you |

| 1 man | |||

| 1 woman | |||

| 2 men | |||

| 2 women | |||

| 1 man and 1 woman |

| Country | Sample | Observations |

|---|---|---|

| Cyprus | 158 | 702 |

| United Kingdom | 79 | 274 |

| Slovenia | 274 | 1091 |

| Montenegro | 321 | 1516 |

| Hungary | 285 | 1289 |

| Iceland | 552 | 2271 |

| Total | 1669 | 7163 |

| (Sample/Census Data) | Cyprus | UK | Slovenia | Montenegro | Hungary | Iceland | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. | 158 | 0.9 m | 79 | 66 m | 274 | 2 m | 321 | 0.6 m | 285 | 10 m | 552 | 0.4 m | 1669 | |

| Gender | ||||||||||||||

| Male | 58% | 48% | 61% | 49% | 80% | 50% | 69% | 49% | 86% | 45% | 69% | 52% | 72% | 1202 |

| Female | 41% | 52% | 38% | 51% | 20% | 50% | 31% | 51% | 14% | 55% | 31% | 48% | 28% | 461 |

| Other | 1% | 1% | - | 0% | - | 0% | 0% | 6 | ||||||

| Age * | ||||||||||||||

| 15–24 | 17% | 15% | 11% | 14% | 16% | 11% | 56% | 16% | 0% | 13% | 8% | 17% | 18% | 306 |

| 25–49 | 66% | 44% | 49% | 40% | 66% | 40% | 41% | 42% | 44% | 42% | 45% | 44% | 50% | 829 |

| 50–59 | 12% | 15% | 18% | 16% | 12% | 17% | 1% | 16% | 23% | 15% | 20% | 15% | 15% | 247 |

| 60–69 | 4% | 13% | 13% | 13% | 5% | 16% | 1% | 15% | 23% | 16% | 18% | 13% | 12% | 200 |

| 70+ | 1% | 13% | 9% | 16% | 1% | 16% | 1% | 12% | 9% | 15% | 9% | 12% | 5% | 87 |

| Household size ** | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 12% | 21% | 17% | 30% | 11% | 30% | 5% | 26% | 11% | 34% | 12% | 36% | 11% | 175 |

| 2 | 19% | 35% | 46% | 35% | 23% | 27% | 10% | 19% | 37% | 31% | 33% | 28% | 27% | 446 |

| 3 | 17% | 16% | 16% | 15% | 23% | 18% | 16% | 16% | 23% | 16% | 20% | 14% | 20% | 326 |

| 4+ | 52% | 29% | 22% | 20% | 44% | 25% | 70% | 40% | 29% | 20% | 35% | 22% | 43% | 722 |

| (Sample/Census Data) | Cyprus | UK | Slovenia | Montenegro | Hungary | Iceland | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. | 158 | 0.9 m | 79 | 66 m | 274 | 2 m | 321 | 0.6 m | 285 | 10 m | 552 | 0.4 m | 1669 | |

| Education | ||||||||||||||

| High-school * | 10% | 22% | 6% | 19% | 22% | 16% | 48% | 17% | 4% | 20% | 12% | 28% | 19% | 314 |

| Bachelor/College ** | 28% | 39% | 34% | 40% | 57% | 55% | 36% | 61% | 84% | 58% | 48% | 35% | 51% | 848 |

| Postgraduate *** | 56% | 40% | 54% | 41% | 20% | 29% | 14% | 22% | 11% | 23% | 38% | 38% | 28% | 471 |

| Others | 6% | - | 5% | - | 2% | - | 2% | - | 1% | - | 2% | - | 2% | 36 |

| Employment | ||||||||||||||

| Company owner | 4% | 6% | 3% | 8% | 4% | 6% | 3% | 8% | 7% | 5% | 2% | 7% | 4% | 61 |

| Employee | 67% | 41% | 63% | 41% | 67% | 41% | 41% | 31% | 73% | 41% | 65% | 50% | 62% | 1037 |

| Full-time education | 17% | 20% | 10% | 21% | 18% | 18% | 22% | 22% | 1% | 17% | 12% | 25% | 13% | 221 |

| Self-employed | 6% | 6% | 9% | 7% | 7% | 6% | 7% | 7% | 5% | 5% | 7% | 7% | 7% | 108 |

| Retired | 2% | 10% | 10% | 13% | 2% | 20% | 3% | 10% | 14% | 16% | 9% | 2% | 7% | 114 |

| Unemployed | 2% | 4% | 4% | 2% | 3% | 2% | 24% | 7% | - | 2% | 2% | 2% | 6% | 101 |

| Others | 2% | 12% | 1% | 7% | 0% | 7% | 1% | 15% | 1% | 14% | 3% | 9% | 2% | 27 |

| (Sample/Census Data) | Cyprus | UK | Slovenia | Montenegro | Hungary | Iceland | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. | 158 | 0.9 m | 79 | 66 m | 274 | 2 m | 321 | 0.6 m | 285 | 10 m | 552 | 0.4 m | 1669 | |

| Household income * | ||||||||||||||

| H | 20% | - | 25% | - | 20% | - | 5% | - | 8% | - | 8% | - | 11% | 191 |

| M | 51% | - | 43% | - | 52% | - | 27% | - | 39% | - | 46% | - | 38% | 635 |

| L | 19% | - | 18% | - | 13% | - | 52% | - | 39% | - | 33% | - | 37% | 609 |

| Not willing to disclose | 10% | - | 14% | - | 16% | - | 16% | - | 14% | - | 13% | - | 14% | 234 |

| Car ownership ** | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 100% | - | 81% | - | 98% | - | 92% | - | 68% | - | 95% | - | 90% | 1504 |

| No | - | 19% | 2% | 8% | - | 32% | 5% | - | 10% | 165 | ||||

| Frequency (Percentage %) | Cyprus | UK | Slovenia | Montenegro | Hungary | Iceland | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trip purpose | |||||||

| Business journey | 4 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 11 (4%) | 23 (7%) | 22 (8%) | 11 (2%) | 72 (4%) |

| Work | 98 (62%) | 47 (60%) | 166 (61%) | 96 (30%) | 178 (62%) | 313 (57%) | 898 (54%) |

| Shopping | 20 (13%) | 13 (16%) | 23 (8%) | 34 (11%) | 31 (11%) | 108 (20%) | 229 (14%) |

| Leisure | 6 (4%) | 5 (6%) | 15 (5%) | 43 (13%) | 21 (7%) | 32 (6%) | 122 (7%) |

| Education | 12 (8%) | 8 (10%) | 41 (15%) | 81 (25%) | - | 45 (8%) | 187 (11%) |

| Passenger pick-up | 10 (6%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 10 (3%) | 10 (3%) | 14 (2%) | 49 (3%) |

| Social visit | 6 (4%) | 4 (5%) | 11 (4%) | 29 (9%) | 20 (7%) | 21 (4%) | 91 (6%) |

| Others | 2 (1%) | - | 3 (1%) | 5 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 8 (1%) | 21 (1%) |

| Total | 158 (100%) | 79 (100%) | 274 (100%) | 321 (100%) | 285 (100%) | 552 (100%) | 1669 (100%) |

| Transport mode | |||||||

| Private car | 137 (87%) | 43 (54%) | 213 (78%) | 187 (58%) | 152 (53%) | 430 (78%) | 1162 (70%) |

| Public transit | 4 (2%) | 13 (16%) | 18 (7%) | 41 (13%) | 88 (31%) | 32 (6%) | 196 (12%) |

| Shared car | 6 (4%) | 1 (1%) | 9 (3%) | 19 (6%) | 3 (1%) | 7 (1%) | 45 (3%) |

| Shuttle | 1 (1%) | - | - | 10 (3%) | - | 2 (0%) | 13 (1%) |

| Combination | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 6 (2%) | 8 (2%) | 11 (4%) | 6 (1%) | 34 (2%) |

| Motorbike | 4 (2%) | - | 1 (0%) | 7 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (0%) | 16 (1%) |

| Private bicycle | 1 (1%) | 11 (14%) | 14 (5%) | 7 (2%) | 8 (3%) | 40 (7%) | 81 (5%) |

| Shared bicycle | - | - | 1 (0%) | 3 (1%) | - | 1 (0%) | 5 (0%) |

| Scooter | - | 1 (1%) | - | 4 (1%) | 1 (0%) | - | 6 (0%) |

| Walking | 4 (2%) | 8 (10%) | 5 (2%) | 28 (9%) | 2 (1%) | 20 (3%) | 67 (4%) |

| Others | - | - | 7 (3%) | 7 (2%) | 18 (6%) | 12 (2%) | 44 (2%) |

| Total | 158 (100%) | 79 (100%) | 274 (100%) | 321 (100%) | 285 (100%) | 552 (100%) | 1669 (100%) |

| Parameters Estimates (t-Test) | Joint Model | Cyprus | United Kingdom | Slovenia | Montenegro | Hungary | Iceland |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AV alt. specific constant (ASC) | −1.02 (−5.25) | 1.78 (1.38) | −2.30 (−1.90) | −0.83 (−1.48) | −0.69 (−2.53) | −1.41 (−2.61) | −1.71 (−2.31) |

| AV ASC RP | 2.11 (3.92) | 2.30 (2.45) | 3.50 (3.53) | −2.53 (−4.00) | −1.32 (−1.38) | 3.77 (4.69) | 4.78 (5.7) |

| CAR ASC RP | 2.43 (5.16) | 4.94 (4.72) | 0.16 (0.05) | −2.10 (−3.06) | 1.85 (2.68) | 2.70 (2.70) | 2.13 (1.53) |

| Travel cost (generic) | −11.00 (−17.80) | −25.50 (−5.40) | −42.90 (−3.92) | −8.78 (−7.47) | −4.51 (−4.61) | −14.90 (−6.35) | −28.00 (−9.66) |

| Travel time D2D (generic) | −5.97 (−15.50) | −12.60 (−5.23) | −23.80 (−3.83) | −6.04 (−6.78) | −2.52 (−4.93) | −6.35 (−6.54) | - |

| Travel time D2D (alt. specific: AV) | - | - | - | - | - | - | −29.90 (−8.52) |

| Travel time D2D (alt. specific: CAR) | - | - | - | - | - | - | −24.70 (−8.68) |

| Woman dummy (AV) | −0.65 (−2.99) | −1.61 (−1.55) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.57 (0.98) | −0.34 (−0.99) | −0.12 (−0.13) | −2.57 (−3.81) |

| High income (AV) | 0.76 (2.70) | 1.81 (1.49) | 3.39 (2.48) | 0.24 (0.43) | 0.57 (0.87) | −0.52 (−0.48) | 2.03 (1.89) |

| Older age dummy (age > 59) (AV) | −1.38 (−5.05) | 1.69 (0.84) | −4.03 (−2.30) | −2.12 (−2.07) | −0.79 (−0.65) | −0.37 (−0.52) | −2.94 (−4.03) |

| Use car dummy (AV) | −0.47 (−2.26) | −4.11 (−2.74) | −2.23 (−1.89) | −0.08 (−0.13) | −0.71 (−2.24) | −1.03 (−1.57) | 0.50 (0.687) |

| Number of individuals | 1669 | 158 | 79 | 274 | 321 | 285 | 552 |

| Number of observations | 7163 | 702 | 294 | 1091 | 1516 | 1289 | 2271 |

| Initial log—likelihood | −3844 | −402 | −156 | −707 | −837 | −649 | −1574 |

| Final log—likelihood | −3200 | −316 | −88 | −540 | −779 | −553 | −756 |

| Number of MLHS draws | 2000 |

| Country | GDP Per Capita (EUR) | VoT (EUR Per Hour) | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joint model | - | 33 | 1669 |

| Cyprus | 23,543 (3) | 30 (4) | 158 |

| UK | 35,748 (2) | 33 (3) | 79 |

| Slovenia | 21,766 (4) | 41 (2) | 274 |

| Montenegro | 7464 (6) | 33 (3) | 321 |

| Hungary | 13,923 (5) | 26 (5) | 285 |

| Iceland | 56,612 (1) | 64 (AV) | 53 (CAR) (1) | 552 |

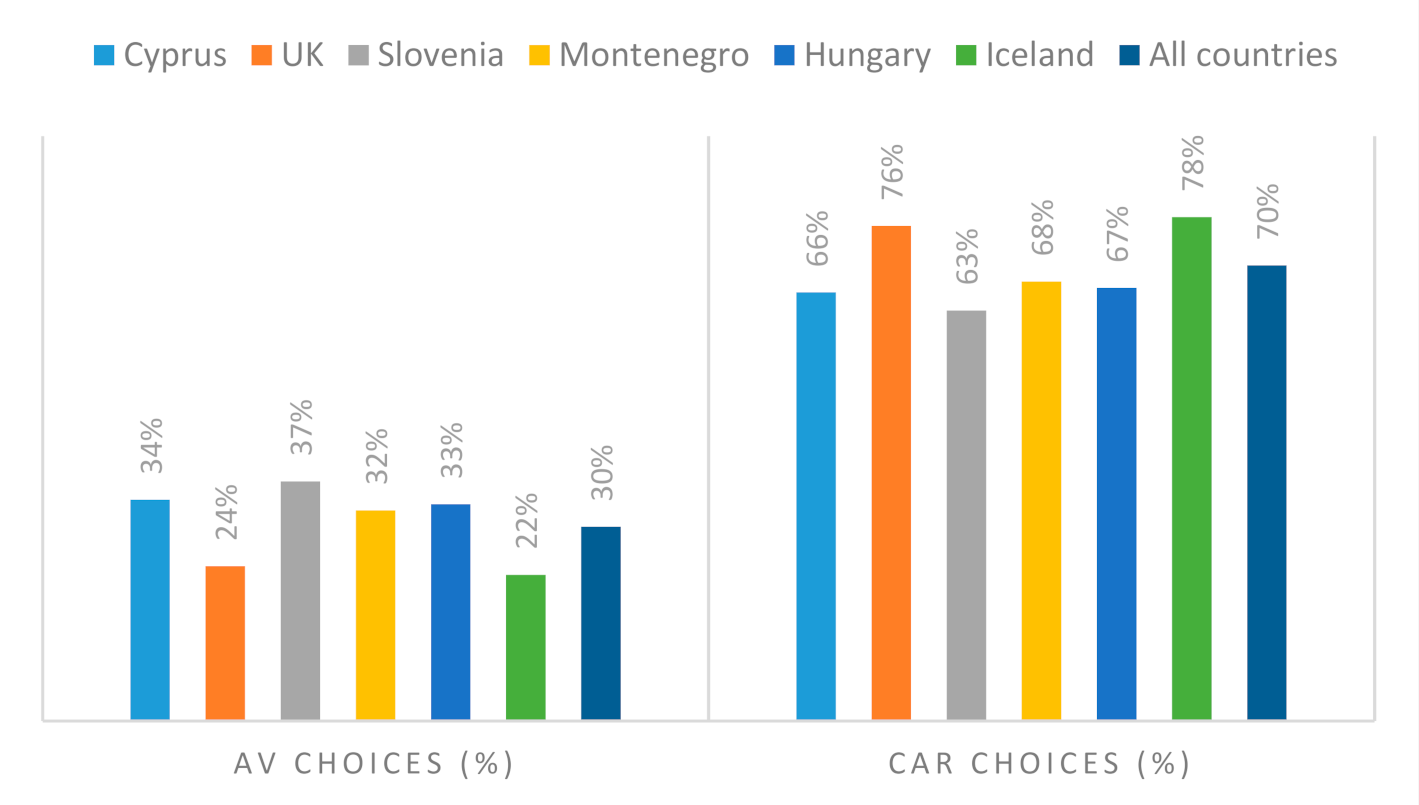

| Cyprus | UK | Slovenia | Montenegro | Hungary | Iceland | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of observations | 158 | 79 | 274 | 321 | 285 | 552 |

| AV choices (%) | 34% | 24% | 37% | 32% | 33% | 22% |

| AV consistent (%) | 11% | - | 10% | 7% | 14% | 5% |

| ASC parameter (t-test) | 1.78 (1.38) | −2.30 (−1.90) | −0.83 (−1.48) | −0.69 (−2.53) | −1.41 (−2.61) | −1.71 (−2.31) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Etzioni, S.; Hamadneh, J.; Elvarsson, A.B.; Esztergár-Kiss, D.; Djukanovic, M.; Neophytou, S.N.; Sodnik, J.; Polydoropoulou, A.; Tsouros, I.; Pronello, C.; et al. Modeling Cross-National Differences in Automated Vehicle Acceptance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9765. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229765

Etzioni S, Hamadneh J, Elvarsson AB, Esztergár-Kiss D, Djukanovic M, Neophytou SN, Sodnik J, Polydoropoulou A, Tsouros I, Pronello C, et al. Modeling Cross-National Differences in Automated Vehicle Acceptance. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9765. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229765

Chicago/Turabian StyleEtzioni, Shelly, Jamil Hamadneh, Arnór B. Elvarsson, Domokos Esztergár-Kiss, Milena Djukanovic, Stelios N. Neophytou, Jaka Sodnik, Amalia Polydoropoulou, Ioannis Tsouros, Cristina Pronello, and et al. 2020. "Modeling Cross-National Differences in Automated Vehicle Acceptance" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9765. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229765

APA StyleEtzioni, S., Hamadneh, J., Elvarsson, A. B., Esztergár-Kiss, D., Djukanovic, M., Neophytou, S. N., Sodnik, J., Polydoropoulou, A., Tsouros, I., Pronello, C., Thomopoulos, N., & Shiftan, Y. (2020). Modeling Cross-National Differences in Automated Vehicle Acceptance. Sustainability, 12(22), 9765. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229765