Abstract

Public procurement is considered an important driver of an economy and has a considerable power in orienting the market, including toward environmental protection policies and strategies. This study examines the green public procurement practiced at the level of local Romanian authorities with the aim of understanding the real context by highlighting the mix between what is required and/or expected from local authorities and what is actually happening in terms of green public procurement. The research is based on the results of an online survey conducted from 16 August 2019 to 18 September 2019. The research results show that green procurement is not a subject approached in many administrative units; however, it appears that environmental protection in the context of public procurement is considered important. In line with other research, our results enrich the current knowledge on green procurement practices at the local government level and indicate that increased regulatory pressure for green public procurement may lead to market development and innovation for green goods and services.

1. Introduction

As demonstrated in practice, public procurement plays an important role in the economy as it is a useful tool for strategic policies, including environmental issues. At the European Union level, public procurement represents 14% of the gross domestic product (GDP) [1], and the public sector market share is about 5–15% [2]. In Japan, the impact of public procurement is even bigger, accounting for 17.6% of the GDP [3]. Green public procurement can be a useful instrument in helping to achieve environmental objectives in a direct (through procurement of goods, services, or works that have a reduced environmental impact) or indirect way (by creating a need for this category and encouraging producers to invest in production, research, and innovation of green lines of product and services). Furthermore, green public procurement targets the overall impact on the environment, taking into account limiting to what is strictly necessary, avoiding unnecessary purchases, encouraging flexibility, and preventing of waste generation.

This is why, at the European Union and national levels, some official steps have been undertaken. The European regulatory framework is reflected by the European Commission Communication “Making Public Procurement work in and for Europe” [4], which includes the priorities regarding procurement practices and investments, as well as by two revised Public Procurement Directives [5,6]. These two directives replaced two older ones from 2004 with the aim of simplifying and making public procurement more flexible, as well as including joint societal objectives, not exceptional environmental ones. The deadline imposed on the member states to transpose these directives into national legislation was April 2016. The European Commission [7] has decided to continue its efforts by publishing a guide to help both public authorities contracting green procurement and companies offering such products, as well as authorities that build policies and strategies in the field.

In Romania, a piece of legislation was adopted [8] with the aim of encouraging environmental protection and sustainable development. For this purpose, the law defines green public procurement as being “the process by which contracting authorities use environmental protection criteria to improve the quality of performances and optimize costs with short-, medium-, and long-term public procurement.” At the end of 2018, a guide for green public procurement that clarifies the minimum environmental protection requirements for certain groups of products and services entered into force [9]. However, a National Action Plan or an equivalent document has not yet been adopted. This unfavorable situation for Romania motivated us to find out what the situation is at the level of the local authorities, what the reasons are for why green public procurement is not implemented on a large scale, and what the suggestions for improving the situation would be.

This study examines the green public procurement practices at the level of local Romanian authorities. There have been some regulatory advancements in this field in Romania, but our objective was to find if the actual practices follow these advancements or the state of the art in this area. This endeavor aimed to clarify the situation by understanding the real context from this point of view and to understand the mix between the requirements, desire, and ability to be involved in this kind of procurement, with the larger aim of contributing to environmental protection. The Romanian case has previously been investigated only from private consumers’ perspective. This paper can add new results to the literature and also present an issue for policymakers at both European and national level based on comprehension of green public procurement at the level of local Romanian administrative authorities.

In the next section, we synthesize the key findings from the literature on green public procurement, focusing on the results and methods of other studies that consider this activity at the local authorities’ level. In Section 3 and Section 4, we describe the data and methodology used and present the main results, and in the final section, we discuss the results and their implications.

2. Review of the Institutional Studies and Scientific Literature

2.1. Institutional Studies at the European Union Level

At the European level, many programs and action plans are in progress. The European Commission publishes some policy findings and reports; one representative package for environmental issues is the Environment Implementation Review, which is now in its second edition [10]. The country reports contain a subchapter dedicated to green public procurement.

The key role of public procurement for the economic strategies and policies is revealed by its weight in GDP. Even if this value is slightly lower in the case of Romania compared to the corresponding value for the European Union (the mean for the period 2012–2015 was 11.3% of GDP in Romania, while the total for the European Union was 13.8% [11], public procurement can be a powerful tool for promoting environmental protection.

Recently, the European Parliament [12] analyzed green public procurement in association with the promotion of a circular economy. In this study, Romania was placed in the last group of countries, which was evidenced by the lack of awareness of circular procurement. Even if a National Action Plan is in the development process, its absence is again placing Romania in the last group of “lagging behind” countries, together with Estonia, Greece, Hungary, and Luxembourg.

At the European level, the situation regarding green public procurement is diverse within member countries. Austria is one of the member states that is very advanced in utilizing green public procurement; in order to help governmental authorities at different levels, a platform and a help desk were implemented for sharing of relevant experiences (http://www.nachhaltigebeschaffung.at/help-desk). Austria is a successful example for implementing a National Action Plan, but also for training, databases, or monitoring process ([10], Country Report Austria). Belgium is also a good example for adopting and implementing the National Action Plan ([10], Country Report Belgium). Cyprus has a long history in green public procurement activities, the first National Action Plan being implemented in 2007 and revised in 2012. An example that can be easily adopted by others is an award for good practices that was introduced in 2014 and extended in 2017. For selected criteria, 50% of the procurement is green, but some categories also exist where the green part of the procurement is between 90% and 100% ([10], Country Report Cyprus). Denmark is considered to be one of the “frontrunners” at the European level when considering the implementation of the National Action Plan; in 2016, a national task force was introduced in order to help the municipalities ([10], Country Report Denmark). Finland made a “Decision on the Promotion of Sustainable Environmental and Energy Solutions” in 2013 and has one of the most ambitious targets—100%—at the central level, but the National Action Plan is only partially implemented ([10], Country Report Finland). France has had a national strategy since 2015; while the European Parliament considers this country as a leader in implementing the green public procurement strategy, the national institutions declared that the initial objectives were only partially achieved ([10], Country Report France). Germany is applying different tools and organizing training sessions to help the authorities involved in green procurement; the National Action Plan is considered to be partially implemented ([10], Country Report Germany). Although some initiatives have been applied at the local level and some awards are offered, the National Action Plan is insufficiently implemented in Greece ([10], Country Report Greece). In Ireland, a National Action Plan was adopted in 2012; however, there are no mandatory requirements, but only specific recommendations; the National Action Plan is considered to be partially implemented ([10], Country Report Ireland). Italy adopted a National Action Plan in 2013 and is working on a revision, and the European Parliament considers this country a “frontrunner”; an interesting aspect is an agreement signed between the Ministry of Environment and the National Anti-Corruption Agency ([10], Country Report Italy). In Luxembourg, no National Action Plan has been adopted, but the law encourages green procurement ([10], Country Report Luxembourg). In Malta, a National Action Plan was firstly introduced in 2011 and entered into evaluation in 2015, and a revised plan is under construction; there is an administrative procedure in place and there are organized courses ([10], Country Report Malta). The Netherlands is known to be an example for good practice—one of the “frontrunners”—as green public procurement was a priority even before the adoption of European directives; this country encourages circular procurement at all levels, pilot projects, and learning and promotion of green procurement ([10], Country Report Netherlands). Portugal is one of the countries with a long history in green public procurement, with a first National Action Plan adopted in 2007 and renewal in 2016; auxiliary measures for encouraging green procurement by the public administration were recently adopted ([10], Country Report Portugal). Spain adopted a National Action Plan in 2008 that was replaced by a new one in 2018; also, in 2018, an Interministerial Commission was established ([10], Country Report Spain). Sweden is another “frontrunner” in implementing the National Action Plan, with a national strategy and a Swedish National Agency for Public Procurement introduced in 2016; green public procurement has been a priority since 2013 ([10], Country Report Sweden). The United Kingdom is also recognized as a leader in the matter; the commitments for green public procurement are political, not juridical ([10], Country Report United Kingdom).

As for the Central and Eastern European countries, the results are not very impressive. The National Action Plan was partially implemented in Bulgaria; this type of procurement is supported by national and European funds ([10], Country Report Bulgaria). Croatia has also partially implemented the National Action Plan and is monitoring green public procurement, but the results are still poor (only 0.5% of the public procurement was registered as green) ([10], Country Report Croatia). In the Czech Republic, a resolution for responsible public procurement accompanied by a methodology was adopted in 2017; the National Action Plan was partially implemented ([10], Country Report Czech Republic). In Hungary, the European directives were transposed into the national legislation in late 2015, but there is no National Action Plan; as announced by Hungarian Public Procurement Authority, the value of public procurement is variable, with 2016 being the worst for the period 2013–2016 ([10], Country Report Hungary). Poland adopted a National Action Plan for the period 2017–2020 in spring 2017, but the requirements are not mandatory; in 2015, green public procurement accounted for 11.40% ([10], Country Report Poland). In Slovakia, a National Action Plan was firstly adopted in 2011, then revised twice, the last revision taking place at the end of 2016; in 2016, only 7.9% of the public procurement was green, and the plan is considered to be partly implemented ([10], Country Report Slovakia). Slovenia is the leader of this category of countries, and is the first one in the European Union that had a mandatory requirement; however, its plan that was adopted in 2009 is no longer in action, and the value of green procurement was 17% in 2015 ([10], Country Report Slovenia).

The Baltic countries did not have remarkable results either. Estonia is one of the countries without an effectual national strategy or National Action Plan, but as determined from the official electronic public procurement website, in 2016, 5.8% of the procurement included green criteria. Latvia has a better position in applying green criteria for public procurement (initial plan adopted for 2015–2017, extended in 2017), and their value accounted for 19% in 2015, 13% in 2016, and 14% in 2017; the National Action Plan is considered to be partially implemented ([10], Country Report Latvia). Lithuania partially implemented the National Action Plan, and the implementation provisions for the period 2016–2020 were adopted in 2015; in 2017, the value of green procurement was 11.3% of the total ([10], Country Report Lithuania).

2.2. Main Results in the Scientific Literature

Systematic reviews of the literature regarding green public procurement clarify essential concepts in this field [13] and the scarcity of studies regarding the role of local government in this research area [14], therefore providing more of a fundament for the present study. Green public procurement is admitted in many studies [15,16,17,18] as a powerful tool for promoting environmental strategies and markets for green products and services. Aside from the benefits, a wide spread of green public procurement is constrained by financial barriers [19] and shortages in managerial succor [20] or information and expertise [21]; most of these studies used surveys as a methodological tool.

A quantitative and qualitative perspective on green public procurement based on a literature review and content analysis is provided by [13]. In Chinese local governments, it was found [22] that awareness of officials with green public procurement regulations was positively associated with the introduction of these practices.

An analysis of green public procurement at the municipal and county level was done for Norway [16] using a survey. Among other observations that resulted from the answers, we note the difficulty of smaller municipalities having special procurement departments and the need to provide guidance for green procurement, as the municipalities’ expertise is narrow. A recent study [23] also discussed the complexity and role of green public procurement in Europe.

The environmental practices were assessed in Portugal (a country with a long experience in green public procurement practices) by making use of a survey [24]. Although the awareness and integration are well perceived, the authors raised the issue of adopting new practices to enhance the environmental actions’ efficiency. An Italian survey was used [25] to determine the influence factors for green public procurement practices.

In recent studies and recently developed strategies, green public procurement has been linked with innovation. A mix of green procurement, innovation, and environmental elements were explored in [26] for the United Arab Emirates; the authors gathered the data from a cross-sectional survey addressed to 50 respondents. Though government spends on promotion of green procurement, half of the respondents were not aware of these initiatives; the authors considered that training programs are needed and that innovation is not sufficient by itself.

A study concerning green public procurement was conducted for Slovakia (a country with a National Action Plan firstly adopted in 2011 and revised two times, which currently considered by the European Parliament to be partially implemented), and the adopted methodological tool was interview questioning [27].

In a comparative study for the public sector [28], the results show a significant variety of sustainable procurement practices, while the authors emphasize the drivers and barriers of procurement practice orientation. The research instrument was also a survey. A different approach [29] studied the positive impact of green public procurement, as it stimulates the use of life cycle costing in public institutions.

The scientific literature dealing with green public procurement also has a segment of studies dealing with the impacts of these procurement practices on specific industries, specifically furniture [30,31], healthcare [32], transport [33], education [34], and agriculture [35].

Research on the role of local governments in enhancing green public procurement is scarce, particularly for less developed countries. For the case of China, there are papers dealing with the importance of local officials’ awareness of the topic [22] and the need for specific training [36]. The practices at the local level in Norway are discussed by [16], while Ref. [37] deals with the case of local governments in the UK. Single regions were analyzed by Ref. [38] for the case of Spain and by Ref. [39] for the case of Latvia.

Published studies directly related to practicing green public procurement in Romania are missing. However, we can identify some studies that are relevant for ecological labeling and Romanian consumers’ attitudes [40] or green consumers in Romania [41,42].

3. Materials and Methods

This study is focused on the perception and implementation of green public procurement at the level of Romania’s local administrative units. The data were collected using an online survey conducted from 16 August 2019 to 18 September 2019; this was the main methodological tool used to analyze the green public procurement issue.

The questionnaire (Supplementary Materials) was addressed to 3227 institutions representing all local administrative units of Romania, as follows: 2861 communes, 217 towns, 103 cities, 40 counties, and 6 districts of Bucharest. The questionnaire contained 24 questions, including 9 single-choice questions, 8 open-ended questions, 3 multiple-choice questions, 3 rating-scale questions, and 1 ranking question. The institutions were sent a link via email for filling out the questionnaire online, as well as an attachment with a document version to be filled out on paper. The initial request to fill out the questionnaire had a 33.5% open rate and a 3.8% click rate on the questionnaire link. The follow-up email had a 27.5% open rate and a 6.1% click rate on the questionnaire link. In total, 112 valid responses were received, representing a 3.5% response rate. Manual survey coding was used to categorize and analyze responses to open-ended questions. The questionnaires that were filled in online were automatically processed by the survey platform, and those received by email were manually introduced into the system.

The responses followed the structure of the administrative units of Romania rather closely (83% of responses came from communes, while communes represent 89% of the country’s administrative units, 11% of responses came from towns, while towns represent 7% of the country’s administrative units, 5% of responses came from cities, while cities represent 3% of the country’s administrative units, and 1% of responses came from counties, the same as their administrative unit representation). The population of the responding units tended to be small or very small; 88% of the respondents represented units with a population of under 10,000 inhabitants (46% of respondents were from units with a population of under 3000 inhabitants). The distribution of responses based on the development regions of Romania is as follows: Northwest 13%, Center 11%, Northeast 25%, Southeast 12%, South 21%, Bucharest-Ilfov 2%, Southwest 10%, and West 6% (see Table 1, below).

Table 1.

Sample details in terms of the structure of the administrative units and development regions of Romania.

A large number of respondents held counselor positions (32 in total, of which at least 14 were public procurement counselors) and inspector positions (28 in total, of which at least 9 were public procurement inspectors). Other positions held by the respondents were public procurement specialist (7 respondents), mayor (5 respondents), secretary (8 respondents), and public administrator (5 respondents).

4. Results

One important thing that emerged from the survey was that green procurement is not a subject approached in many administrative units. Half of the respondents indicated that the topic of green procurement was never discussed in their locality/administrative unit, and just one-third indicated that such a discussion of the subject existed. The other respondents did not have any information regarding this topic. We can note that just 10% of the respondents from towns and cities indicated that such a topic was never discussed, and almost half did not know—probably due to the higher complexity of their institution’s organization.

However, it appears that environmental protection in the context of public procurement appears to be present in many instances. Less than 5% of the respondents indicated that environmental protection is never considered in the process of public procurement, while 31% indicated that such considerations exist in all procurement activities. A total of 32% of the respondents indicated that such concerns are a common occurrence and 25% indicated that they sometimes appear. These answers might appear to conflict with the ones provided for the previous question.

All of this considered, 90% of the respondents believed that green procurement should be stimulated.

Specific training related to green procurement is very seldom organized. Just 5% of the respondents indicated that such training took place in their institutions, while 87% indicated that such activities did not take place (the remaining respondents did not know). The percentage of respondents indicating such training taking place was significantly higher (16%) for the respondents from towns and cities.

The results of the survey suggest that green procurement is of average importance for the consulted institutions. We note that 10% of the respondents indicated that green procurement is the top priority for their institution, 30% indicated it as an average priority, and 30% indicate that it has a low or very low priority. We consider that these results are in line with reasonable expectations. Taking into account known budgetary constraints for most administrative units, we could safely assume that green procurement was not on top of the list regarding their consideration. In fact, it is rather surprising to note that 10% of respondents indicated green procurement as their most important concern. It appears that the type or size of administrative unit has little influence in what concerns the perception of the importance of green procurement.

In the procurement process, 56% of the responding units indicate the use of selection criteria or technical requirements that encourage the offering of high levels of environmental performance (25% of the respondents could not answer this question). This answer provides a rather positive perspective regarding the perspectives of implementing a national plan for green public procurement when such a plan will become available. Again, there appears to be little variation in this concern based on the size or type of administrative unit. Among the examples provided by the respondents regarding green criteria used in 2018 were those related to the level of energy or fuel consumption (mentioned by eight respondents) and the use of recycled paper (mentioned by six respondents).

In line with existing expectations, among the examples of goods and services complying to green procurement criteria, the respondents indicated mostly paper products and IT equipment, with 40 and 29 mentions, respectively.

When asked to approximate the percentage of green procurement in total procurement spending in 2018, the participants’ responses were diverse. Ten respondents (three of which were from towns) indicated a level of 10%, five respondents indicated 5%, and three respondents indicated 20%, while most answered that they did not know or that such green procurement is not conducted. From the start, this question was considered difficult, and it was included in the survey simply as an exploratory tool that would provide some grounding for future studies.

Perhaps rather surprisingly, most respondents (55%) appeared confident that they had a good understanding of what green procurement is based on the definition used in the regulatory framework. However, these answers did not reflect the actual level of specific understanding, just what the respondents believed they understood and knew about the subject.

When asked to rank the relevant factors for public procurement decisions based on importance, the most important factor appeared to be the price–quality ratio, followed by (in this order) initial price, life-cycle cost, impact on environment, previous experiences, stimulation of businesses from the locality, and other factors. We therefore note that based on these answers, the impact on the environment appears to be an average concern.

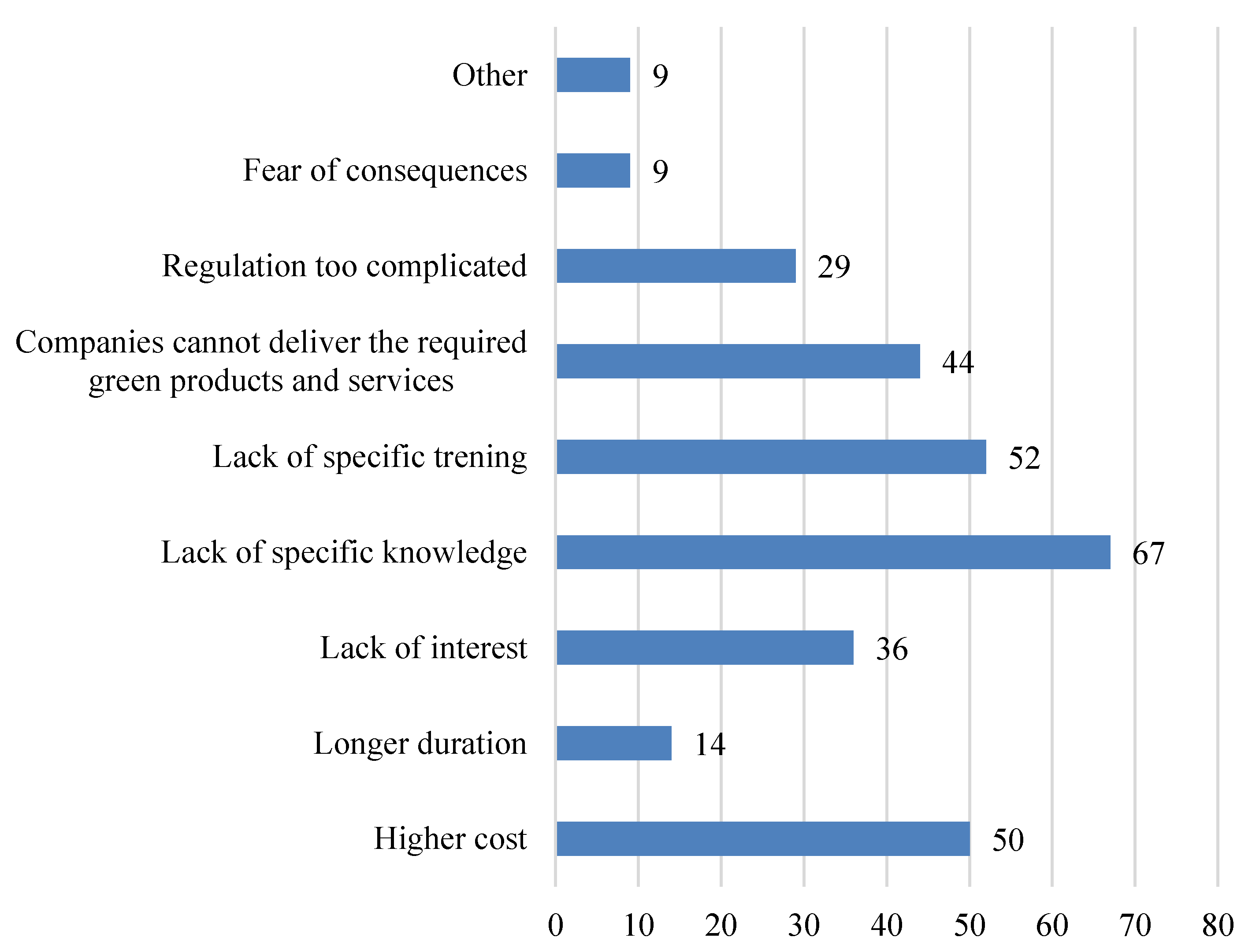

An encouraging perspective is that 90% of the respondents believed that green public procurement should be stimulated. Based on the respondents’ opinions (Figure 1), the most important factors that inhibit the implementation of a more consistent policy regarding green procurement are the lack of specific knowledge (67 respondents), the lack of specific professional training (52 respondents), the higher cost of green procurement (50 respondents), and the fact that companies cannot provide the required green goods and services (44 respondents). Other factors are the general lack of interest in the topic (36 respondents), the complexity of the regulatory framework (29 respondents), or the increased duration of the procedures (14 respondents). Specific training and information dissemination can approach the first two issues rather easily.

Figure 1.

Main difficulties in implementing a more consistent policy in the field of green public procurement (number of responses). Source: authors’ representation, data from the conducted survey.

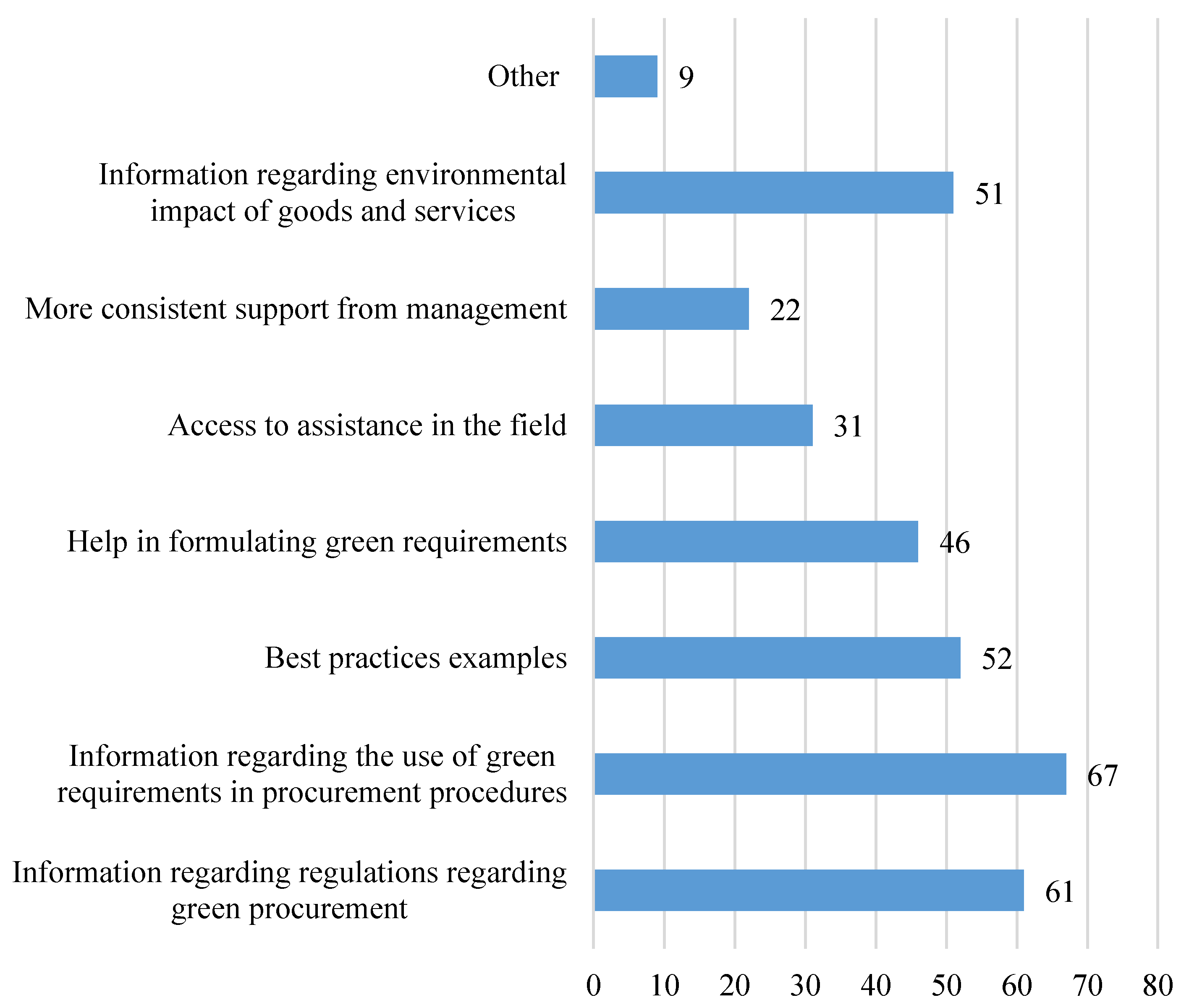

In order to stimulate the approach of environmental consideration in the public procurement processes of their institutions, the respondents indicated (Figure 2) the need for information about the manner in which environmental requirements can be included in the procurement procedures (67 respondents) and for information about specific legal requirements (61 respondents). Other important aspects are related to the environmental impacts of goods and services as well as to success stories (52 responses each).

Figure 2.

What should be done to improve the respondents’ institutions in green procurement. Source: authors’ representation, data from the conducted survey.

The respondents indicated that the value of acquisitions was not a relevant factor (54%) in the decision-making process regarding green procurement.

The familiarity of the respondents with the specific national and European Union regulatory frameworks was somewhat low. On a scale from 1 to 5, in which 1 indicates very familiar and 5 indicates not at all familiar, the average answer was 3.63 for familiarity with the national regulatory framework for green procurement and 3.88 for familiarity with European Union framework. These results partially contradict the responses to a previous question in which the respondents indicated their perceived level of understanding regarding the concept of green public procurement. The familiarity with the regulatory framework is only marginally better at the town or city level (3.37 for the national framework and 3.74 for the European Union framework).

5. Discussion

The response rate of our study was rather low at 3.5%, and this aspect represents a limitation of the study that needs to be considered when interpreting the results. However, the response rate was better than the one reported in comparable studies [22,36]. Possible explanations for this limitation are the topic of the survey, which was probably not of very high interest to many survey subjects [43], the low digitalization level of the local administrations in Romania, and the lack of a database or contacts occupying relevant positions in the target institutions. Future research would need to improve the subjects’ database and work with a simpler questionnaire in order to improve the response rate and the quality of the results.

It appears that there is a lack of specific information and training at the level of local administrations regarding green public procurement. It was important to note that just 5% of our survey respondents were aware of any form of specific training at their workplace. It appears that there is ample opportunity to use training and information dissemination as tools for improving the understanding of the meaning and importance of green public procurement, particularly at the level of communes. The answers to the open-ended questions also frequently mentioned the need for specific training and the supply of adequate information. This conclusion is consistent with findings reported by other authors [36,44].

One issue that emerged and requires increased attention concerns the capacity of the providers of goods and services to offer green alternatives and to do so at affordable prices. A number of respondents indicated a need to take supply-side measures to stimulate green public procurement. Our research also indicates that, in line with the findings of other authors [45], increased regulatory pressure for green public procurement may lead to market development and innovation for green goods and services.

Rather unexpectedly, our study did not reveal the complexity of the regulatory framework to be a major issue in the development of green public procurement practices. Of course, a significant number of respondents indicated a need to simplify and clarify specific regulations. However, based on previous investigations of local authorities’ opinions on public policies and regulations, we would have expected a higher degree of discontent with the complexity of specific regulations. The representatives of administrative units appear to have a positive attitude towards green procurement, not perceiving it as a constraint, but as a necessity for the good development of their communities.

A top-down approach might provide good results in the efforts to encourage green public procurement. Though many respondents to our study indicated that the decisions regarding public procurement were made by the public procurement department of the institution or by the local council, a high number of respondents indicated the mayor/institution manager as the decision-maker (52 respondents indicated a single person as decision-maker, identified as the mayor, manager, or authorizing officer). Virtually all these situations occurred in communes. In addition, it appears that the more decentralized the procurement decision-making process is, the more attention is given to environmental aspects.

It was interesting to note that the approach to green public procurement issues varied based on the type of administrative unit, with small differences between small communes and larger towns, for example.

This paper contributes to the understanding of how local authorities approach the issue of green public procurement based on the case of Romania. It is an exploratory study that opens the way to further research at the regional level, which could contribute to better public policy and operational alignment.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/23/10169/s1, Questionnaire Regarding Green Public Procurement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.C. and I.L.; methodology, T.C. and I.L.; formal analysis, T.C. and I.L.; investigation, T.C. and I.L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C. and I.L.; writing—review and editing, T.C. and I.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- European Commission. Single Market Scoreboard. Public Procurement Reporting Period: 01/2018–12/2018. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/scoreboard/_docs/2019/performance_per_policy_area/public_procurement_en.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- European Commission. EU GPP Training Toolkit. Module 1: Green Public Procurement (GPP)—An Introduction. 2019. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/index_en.htm (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Ho, L.W.P.; Dickinson, N.M.; Chan, G.Y.S. Green procurement in the Asian public sector and the Hong Kong private sector. In Natural Resource Forum; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2010; Volume 34, pp. 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Communication. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Making Public Procurement work in and for Europe. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/25612 (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- Council of the European Union and the European Parliament. Directive 2014/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on public procurement and repealing Directive 2004/18/EC. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014, 94, 65–242. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union and the European Parliament. Directive 2014/25/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on procurement by entities operating in the water, energy, transport and postal services sectors and repealing Directive 2004/17/EC. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014, 94, 243–374. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Buying Green! A Handbook on Green Public Procurement, 3rd ed.; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Romanian Parliament. Law no. 69/2016 on green public procurement. 2016. Official Monitor, Part I, no. 323. Available online: https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/geydmmzygmzq/legea-nr-69-2016-privind-achizitiile-publice-verzi (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Ministry of the Environment. The Green Public Procurement Guide, which contains the minimum environmental protection requirements for certain groups of products and services that are required in the specifications. 2018; Official Monitor, Part I, No. 954. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Environment Implementation Review. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/eir/country-reports/index_en.htm (accessed on 26 September 2020).

- European Commission. Public Procurement Indicators 2015, DG GROW G4—Innovative and e-Procurement. 2016. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/20679/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native (accessed on 26 September 2020).

- Neubauer, C.; Jones, M.; Montevecchi, F.; Schreiber, H.; Tisch, A.; Walter, B. Green Public Procurement and the EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy, European Parliament, Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy. 2017. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2017/602065/IPOL_STU(2017)602065_EN.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2020).

- Cheng, W.; Appoloni, A.; D’Amato, A.; Zhu, Q. Green Public Procurement, missing concepts and future trends—A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 770–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, E.; Andre, K.; Axelsson, K.; Benoist, L. Advancing sustainable consumption at the local government level: A literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 1450–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, L. Buying into our future: The range of sustainability initiatives in local government procurement. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2007, 16, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelsen, O.; De Boer, L. Green Procurement in Norway: A survey of practices at the municipal and county level. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 91, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, K.F.; Halpern, B.H.; Rendon, R.G.; Kidalov, M.V. Corporate social responsibility and public procurement: How supplying government affects managerial orientations. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2013, 19, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Iraldo, F.; Frey, M. The effect of environmental regulation on firms’ competitive performance: The case of the building and construction sector in some EU regions. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 2136–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, H.; Di Sisto, L.; McBain, D. Drivers and barriers to environmental supply chain management practices: Lessons from the public and private sectors. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2008, 14, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, C.; Hallstedt, S.; Robert, K.H.; Broman, G.; Oldmark, J. Assessment of criteria development for public procurement from a strategic sustainability perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Geng, Y.; Sarkis, J. Motivating green public procurement in China: An individual level perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 126, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Xue, J.; Yang, L.; Shi, B. Enhancing green public procurement practices in local governments: Chinese evidence based on a new research framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mélon, L. More Than a Nudge? Arguments and Tools for Mandating Green Public Procurement in the EU. Sustainability 2020, 12, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueiro, L.; Ramos, T.B. The integration of environmental practices and tools in the Portuguese local public administration. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 76, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Iraldo, F.; Frey, M.; Daddi, T. What factors influence the uptake of GPP (Green Public Procurement) practices? New evidence from an Italian survey”. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 82, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlNuaimi, B.K.; Khan, M. Public-sector green procurement in the United Arab Emirates: Innovation capability and commitment to change. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zwan, J. A qualitative study on the status and prospects of Green Public Procurement in Slovakia, research paper Agenda for International Development. Available online: https://www.a-id.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2.aid-researchpaper-judith-191118.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2020).

- Brammer, S.; Walker, H. Sustainable procurement in the public sector: An international comparative study. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2011, 31, 452–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giacomo, M.R.; Testa, F.; Iraldo, F.; Formentini, M. Does Green Public Procurement lead to Life Cycle Costing (LCC) adoption? J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2019, 25, 100500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhgrena, M.; Milios, L.; Dalhammar, C.; Lindahl, M. Public Procurement of Reconditioned Furniture and the Potential Transition to Product Service System Solutions. In Proceedings of the 11th CIRP Conference on Industrial Product-Service Systems, Zhuhai, China; Hong Kong, China, 29–31 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Braulio-Gonzalo, M.; Bovea, M. Criteria analysis of green public procurement in the Spanish furniture sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, K.; Rahman, S. Green public procurement implementation challenges in Australian public healthcare sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 152, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldenius, M.; Khan, J. Strategic use of green public procurement in the bus sector: Challenges and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Bargues, J.L.; Ferrer-Gisbert, P.S.; González-Cruz, M.C. Analysis of Green Public Procurement of Works by Spanish Public Universities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindström, H.; Lundberg, S.; Marklung, P. How Green Public Procurement can drive conversion of farmland: An empirical analysis of an organic food policy. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 172, 106622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, B.; Xue, Q.; Wang, Q. Improving the green public procurement performance of Chinese local governments: From the perspective of officials’ knowledge. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2019, 25, 100501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, J.; Jackson, T. Sustainable procurement in practice: Lessons from local government. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2007, 50, 421–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Bargues, J.L.; Ferrer-Gisbert, P.S.; Gonzalez-Cruz, C.; Bastante-Ceca, M.J. Green Public Procurement at a Regional Level. Case Study: The Valencia Region of Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvagzne, A.; Kotane, I.; Krivasonoka, I. Use of Green Public Procurement of Food in Rezenke Municipality. In Proceedings of the 26th International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development—“Building Resilient Society”, Zagreb, Croatia, 8–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dinu, V.; Schileru, I.; Atanase, A. Attitude of Romanian Consumers Related to Products’ Ecological Labelling. Amfiteatru Econ. 2012, 14, 8–24. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, T.; Bostan, I.; Manolica, A.; Mitrica, I. Profile of Green Consumers in Romania in Light of Sustainability Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6394–6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, V. Green Behaviour of the Romanian Consumers. Econ. Insights Trends Chall. 2014, 3, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, W.; Yan, Z. Factors affecting response rates of the web survey: A systematic review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Annunziata, E.; Iraldo, F.; Frey, M. Drawbacks and opportunities of green public procurement: An effective tool for sustainable production. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1893–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleda, M.; Chicot, J. The role of public procurement in the formation of markets for innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 107, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).